A brief history of international interlibrary lending and document supply

Abstract:

In this chapter a brief and general background for interlibrary loan in libraries is given. An overview of the historical development of international borrowing and lending practices and document supply is also provided.

Introduction

At a fundamental and basic level, libraries of all sizes, types and locations select, acquire, organize, preserve and provide access to information. In addition to circulating these materials to a generally well-defined set of affiliated users, libraries have also – over the past several hundred years – found ways to share resources amongst themselves. The principle of providing access to items not owned locally has deep roots in the notion that no single library ever could or would own the sum total of knowledge as it is captured in the published documents of the time. While the idea of sharing resources cooperatively beyond the institutional walls of any particular library is a long-established one, the actual and successful practice of doing so is fairly recent.

For many hundreds of years, libraries simply did not circulate materials. For early libraries, preserving knowledge through the systematic acquisition of printed resources was of primary importance. It was not uncommon to chain books to library shelves to prevent loss (Hoare, 1994). Providing for the intellectual needs of potential library users was of secondary or little importance. In the days when there were more books than there were people who could read them, scholars heard by word of mouth where an item might be located and traveled there to view it (Kilpatrick, 1990).

Although lending of materials was rare, it was not entirely unknown. In the Hellenic period, ‘manuscripts were delivered between Athens and Alexandria to be copied and returned’ (Aman, 1989: 84). During the Middle Ages, monasteries in Italy and German engaged in an informal exchange of religious manuscripts (Condit, 1937) and in roughly the same time period, manuscripts were sometimes copied and shared between major libraries in the Islamic world (Aman, 1989; Miguel, 2007).

In 1634, a French nobleman, Nicolas Claude Fabri de Periesc, tried to arrange for a mutually beneficial, reciprocal exchange of manuscripts between the Royal Library in Paris and the Vatican Library in Rome. After more than a year of negotiations, the exchange was near completion when a sudden embargo was placed on the shipment of manuscripts by the French government. Although the physical delivery of the manuscripts was ultimately unsuccessful, the work by de Periesc is generally cited as the first effort to establish a formal lending system in Europe (Gravit, 1946).

Also at approximately the same time, document copying and exchange existed in China (Fang, 2007). According to Rong Cao, a 17th century book collector:

An agreement can be struck whereby the owners of the respective volumes will order the works in question carefully copied and proofread before, with the period of a month or so, the copies will be exchanged between the two libraries. This method promises a number of distinct advantages: First, good books are never required to leave the libraries to which they belong. Second, we perform a meritorious deed in relation to the ancients. Third, one’s own collection grows daily richer. Fourth, books from the north and the south intermingle and circulate freely. (Campbell, 2009)

Over the next 250 years, with the rapid increase and production of printed knowledge, many of the great university and national library collections of the world were built, including Britain’s Bodleian Library, the French Royal Library, and the Ambrosian in Milan (Hovde, 1994). It was, however, not common practice for libraries to lend these recently acquired materials and, in some cases, doing so was prohibited by law (Miguel, 2007). Book exchanges between libraries that did occur were individually, and laboriously, negotiated. In Estonia, for example:

Books were lent to readers … on the basis of personal applications to the Rector of the University, while the decision was made by the university council and library authorities. It was a long procedure with the exchange of many letters (confirming, ordering, sending, arriving, posting back and receiving). Sometimes the books were sent by post but mostly embassies were engaged in posting them. (Lushchik et al., 2006)

This slow and elaborate method of borrowing and lending remained the prevalent model throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

‘We should develop some system’

It was during the 19 th century that a call to formalize the philosophy and principles of resource sharing was first heard amongst the industrialized nations of the world. In the United States, as early as 1849, librarians began to ask: ‘Is there any regulation by which books may be lent by courtesy to persons at a distance? If so, what is it?’ (Kilpatrick 1990, 23). In practice, at libraries throughout New England, books were already and frequently being lent to clergymen and ‘other responsible literary gentlemen’ known to be engaged in scientific pursuits at the discretion of the librarian, a standing library committee or a special vote (Feipel, 1910).

In the first issue of Library Journal, published in September of 1876, a letter written by Samuel S. Green of the Worcester (Massachusetts) Free Public Library appeared, in which he wrote:

It would add greatly to the usefulness of our reference libraries if an agreement should be made to lend books to each other for short periods of time … I am informed that a plan of this kind is in operation in Europe, and that in many places it is easy to get through the local library books belonging to libraries in distant countries.

(Green, 1928: 79–80)

Although it is not cited in this statement, Green may have been referring to a recent action by the Austrian government, and followed by other European countries, that allowed local libraries to lend materials to foreign libraries without permission from the central government (Gilmer, 1994).

An etymological product of the 19th century, the term ‘interlibrary loan’ also began appearing with some regularity amongst librarians towards the end of the century. By 1888, Melville Dewey, while also proposing a standardized request form that could be used by all libraries, was able in his own inimitable style to state: ‘Interlibrary-loans which wer a litl while ago almost unknown ar now of daily occurrence’ [sic] (Dewey, 1888: 405). In fact, by the early 1900s, the start of what would become a workable system for sharing resources was beginning to take shape as this example illustrates:

A graduate of Bryn Mawr who is studying in Berlin for a doctor’s degree wished to use a Greek volume of the year 1255, which is in the National library at Paris. The National library of Berlin undertook to get it for her. The director accordingly wrote a note to this effect to the German ministry of education. The ministry of education wrote to the foreign office and the latter wrote to the imperial chancellor. The imperial chancellor sent the request to the French ambassador to Germany and then it was up to France. The French ambassador at Berlin wrote to the German ambassador at Paris, who wrote to the French foreign office, and so on … till the request finally reached the director of the Paris National library. This red tape occupied five months, but the student is now able to read the precious volume in the presence of one of the custodians of the Berlin library. (‘Borrowing’, 1908: 17)

In the years leading up to the First World War, Germany and other countries throughout Europe were borrowing and lending to an extent that these informal and individually negotiated exceptions and agreements between libraries and countries would soon become unsustainable (Drachmann, 1928; Hicks, 1913). As a result, even though ILL was not yet part of a system or network, European attempts to formalize procedures and standardize policies were already in the works.

Early in the 20th century, American editor and publisher, Richard R. Bowker, called on the American Library Association (ALA) to also begin this work:

We should develop some system that will enable a library first of all to know where a book ought to be found, and secondly, if there is no special place for it, some means of asking who has it. (1909: 156)

In 1909, the U.S. Library of Congress, somewhat reluctantly following Europe’s lead, established an official policy for lending materials to other national libraries (Stuart-Stubbs, 1975). First proposed in 1917, the ALA published its first ‘Code of Practice for Inter-Library Loans’ in 1919 (‘Code’, 1928).

Following the disruption of World War I, the move to create standardized procedures for borrowing and lending internationally resumed in Europe, the United States and Asia. It soon became clear, however, that development was going to proceed in an uneven manner with practices that were ‘confusingly various’ (Colson, 1962: 259). This pattern, ‘a result of action taken by individual countries and, in many cases, by individual libraries’ (Filon, 1950: 76) would have long-term effects for both national and international interlibrary loan systems. At this time, many countries worked to build or strengthen internal ILL services, often through a centralized national-regional system similar to one emerging in Britain, before seeking to supplement internationally. Others appeared somewhat reluctant to share at all, as evidenced by the Librarian of Congress in 1925 who declared: ‘We are so much the trustees for the scholars of tomorrow that we must not let the scholars of today wear out the work of the dead scholars of the past’ (Ashley, 1928: 65).

Underlying principles and reasonable rules

Despite some high-profile parochialism, international library cooperation did increase throughout the 1920s and 1930s. With the aid of the League of Nations Committee on Cooperation and later the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) by 1934 nearly 40 countries worldwide were engaged in some type of systematic international resource sharing (Miguel, 2007). In 1936, IFLA produced a code of rules for interlending (Filon, 1950).

Both the 1917 ALA code and the 1936 IFLA codes dealt, for the first time, with the most basic questions of interlibrary loan:

![]() For how long shall it be lent?

For how long shall it be lent?

![]() Who shall be qualified to borrow or request?

Who shall be qualified to borrow or request?

The creation of an international system of interlibrary lending by IFLA was based on a uniform code of regulations, using for the first time standardized forms. By 1939, the IFLA code and form had been adopted by 19 countries (Rayward, 1994).

Even as policies and procedures were being worked out in individual countries, World War II disrupted cooperative resource sharing ventures. After the war, as libraries in Europe and Asia struggled to return to some kind of normalcy, many of the formal reciprocal agreements and patterns established in the pre-war years had to be renegotiated, with UNESCO and IFLA stepping in to help counterbalance the effects of war losses (Filon, 1950). In the case of the United States, there appeared to be a general reluctance to rejoin the international ILL community. Rather than attempt to borrow from libraries devastated by war, U.S. libraries took advantage of the Farmington Plan. This program, which ran from 1948 to 1972, ‘sought to make certain that at least one copy of every foreign book or pamphlet that might reasonably be expected to interest a research worker in the United States would be acquired by an American library’ (Gaines, 1994: 193).

With a wave of unforeseen technological change on the horizon, this was a period when collections and infrastructure were built. For the libraries of the world this was also a time when the principles and practice of interlibrary loan had to be reaffirmed, with a restatement of an old ideal: ‘Knowledge and ideas are international and no one who seeks them can be satisfied for long with what is published in his own country’ (Filon, 1950: 76).

Document delivery – Part I

A word should be said here about the history of document supply, or more broadly, the use of non-returnables in the interlibrary loan environment. Copying entire or extracted documents that could be sent in lieu of the original has an even longer tradition than monographic book exchange. To preserve valuable originals from damage and to reduce the cost of shipment, scribes during the Islamic Empire copied thousands of manuscripts and transferred them among the major libraries and mosques in Damascus, Baghdad, Fez and Cairo (Aman 1989). And, while the early attempt by de Peiresc to negotiate the loan of a manuscript held in Rome was unsuccessful, an officially sanctioned copy of the work was eventually provided (Gravit, 1946).

A practical alternative to shipment of the original, especially for libraries that were reluctant to circulate materials either locally or internationally, handwritten and later typewritten copies were also time-consuming and expensive to produce and frequently of poor quality. With the increase in both monographic and journal publication, however, an improved copy method became available. Throughout the late 1800 s, both the Bibliothèque Nationale and the British Museum provided photography equipment and dark rooms for patrons to use to make copies in-house (Ballou 1956). In 1900, a photoduplication process was developed in France and the Photostat was eventually adopted by large research and academic libraries in both Europe and the United States. For most libraries, this device and others like it were far too expensive and difficult to operate for wide implementation. Likewise, microform technologies that developed during this period, though useful for copying and preserving originals, were generally only taken up by large institutions (Ballou, 1956). And some ideas were simply never adopted at all, such as the construction of a pneumatic tube system (Gosnell, 1957) or the full exploitation of ‘the capacities of television as a means of transmitting library materials’ (Coney, 1958: 379). Developments in duplication and transmission technology, however, were to come which would revolutionize the operation of interlibrary lending and borrowing not only for non-returnables but for all format types.

Discover, locate, request, deliver

At mid-century, libraries around the world were working to improve internal processes, particularly circulation and bibliographic operations. Although resource sharing was touted as a cornerstone of international cooperation, in reality many libraries, including those in the United States, did not routinely borrow or lend abroad, citing geographic distance, the lack of a national clearing house and currency problems as the chief obstacles (Colson, 1962). Other challenges also impacted international resource sharing. Despite long-term efforts to compile and maintain accurate union catalogs and union lists of serials, locating a particular title in a specific library was still an extremely difficult, time-consuming, labor-intensive manual task. For many scholars traveling to the owning library was the only access option. Requests for materials were sent by surface mail. Shipment of requested material to and from the borrowing library was expensive, slow and prone to loss or damage. Only after the ALA approved its International Interlibrary Loan Procedures for United States Libraries in 1959, which generally adopted most of IFLA’s 1954 rules, did cooperation and mobilization of resources begin to change (Gilmer, 1994).

Forms

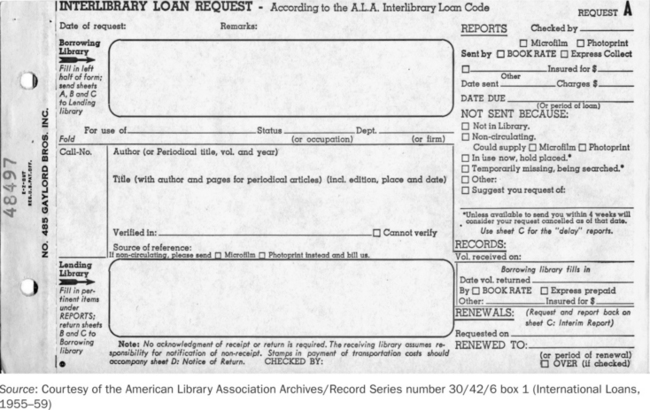

Although global resource sharing had outgrown the hand-tailored personal exceptions of the previous century, many of ‘the little amenities’ lingered, both slowing down and complicating the process while also detracting from its usefulness and value to the scholar (Wright 1952). One solution for handling the myriad of details involved in an ILL transaction was the acceptance and application of some widely accepted rules. But, with different countries, traditions, customs and practices, these rules had to constitute a ‘kind of average standard more than a set of statutes in the strictest sense’ (Wehefritz, 1974: 20). The use of request forms was an early such attempt at uniformity but one that still displayed a great deal of variation in size, shape and required fields. In 1951, the University of California developed a four-part carbon form that, along with a 1968 revision to the form, was widely adopted and used by U.S. libraries (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Interlibrary Loan Request Form No. 485, Gaylord Bros. Inc. Source: Courtesy of the American Library Association Archives/Record Series number 30/42/6 box 1 (International Loans, 1955–59)

Originally sent through the mail and later by teletype or fax, the forms were eventually abbreviated and altered to meet new bibliographic utility and network requirements for transmission. Additionally, a photocopy order form was developed by ALA in the early 1960s and was revised in 1976 to accommodate major changes in U.S. copyright law and rapidly changing new technology. Likewise, IFLA adopted a standardized form in 1936, which has undergone several revisions, and is still used when a paper form is needed (Wehefritz, 1974).

Networks

It would be fair to say that ‘the nature and function of ILL has changed more since 1960 than any time in the history of libraries, primarily because of the combined effect of library networks and automated systems’ (Kilpatrick, 1990: 30). The convergence of computing and telecommunications, which began in the 1960s, brought an overwhelming array of new products, services, equipment, tools, and programs to libraries. Since it would be impossible to detail all the innovations that occurred during the remaining decades of the 20th century, only a few will be mentioned here.

Regional bibliographic or resource centers existed in the U.S. since the 1930s, primarily to provide cooperative cataloging and resource sharing support to public libraries that individually could not afford these services. By the 1960s, these networks began to focus on automation and it was through these networks that library automation was introduced, along with pioneering efforts at statewide resource sharing (Davis, 2007). During this period, 54 libraries formed the Ohio College Library Center, later to become the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC). In the early 1970s, the OCLC online union catalog, now known as WorldCat, was rolled out and sold to libraries across the U.S. In 1979, the first interlibrary loan messaging subsystem appeared. Both products automated and transformed the way interlibrary loan was conducted. By 2010, WorldCat had become the world’s largest library catalog with more than one billion holdings, representing materials held in more than 72,000 libraries in 171 countries. The interlending arm of OCLC, WorldCat Resource Sharing (WCRS) is currently used by more than 10,000 libraries in 40 countries to process and manage ILL requests.

Document delivery – Part II

As monographic resource sharing was changing with the expansion of bibliographic utilities and networks so too were document delivery systems based on improvements in transmission technologies. In Canada, for example, the National Research Council Canada Institute for Scientific and Technical Information (commonly called CISTI), used IBM punch cards to create the first automated union list of scientific serials that also matched requests with published materials from commercial databases (Krym and VanBuskirk, 2001).

The delivery of documents from this collection gradually evolved into a national service. In 1964, telex was adopted to improve document ordering, and in 1979, delivery was further speeded with the installation of the first fax machines. Photocopying was replaced with scanning and faxing was replaced by electronic transfer. The ease and speed with which documents could now be requested and supplied changed the resource sharing landscape.

Interoperability

With the development of each new tool, interlibrary loan practices and processes were increasingly automated. New and competing products and providers improved some services but lack of integration between search, request and delivery systems complicated others. To ease some of the barriers between systems, the National Library of Canada, along with the Scandinavian library community, developed an international standard that allows libraries to communicate with each other about interlibrary loan requests in a machine-readable format. ISO ILL 10160 and 10161 protocols, developed during the 1990s, allow for a uniform message communication system which makes interoperability between all types of systems and peer-to-peer communication using a single interface possible (Shuh, 1998).

Automated interlibrary loan, with its tangle of processing and communication messages crossing multiple institutions and platforms, required the use of centralized service utilities such as OCLC, RLIN, WLN or DOCLINE but there was little or no linking between these systems. The development of ISO ILL standards, along with other computer-to-computer protocols such as Z39.50, NCIP and OpenURL, permits previously isolated machines (and libraries) to talk to one another. These standards have been instrumental in making local ILL systems perform more efficiently and effectively while at the same globalizing the community of interlending partners. By streamlining the transmission of requests between and among diverse systems, the way was paved for a new generation of ILL and resource sharing tools that allow for such time-saving activities as unmediated borrowing.

Additional technological developments during this period, such as fast and inexpensive image scanners, document transmission software, and ILL management systems, also impacted the way interlibrary loan was accomplished both locally and internationally. In the early part of this century, many of these automation technologies had been widely adopted by libraries of all types, in locations around the world. While automation and technology have become integral to library service, making it easier and faster for both libraries and library users to locate, request and receive information, automation has also created an extremely complex network of vendors, products, providers, procedures, codes of practice, and guidelines. For libraries actively engaged in resource sharing, the statement ‘So many patrons, so many peers, so many utilities’ (Chudnov, 2001) accurately reflects the current landscape.

The last mile

The existence and prevalence of global resource sharing today is the product of historical developments in communications, transportation and economic necessity (Straw, 2003). The philosophical groundwork and motivation to engage in this cooperative activity are deeply rooted in the tradition of libraries. Early in the last century, a librarian at Louisiana State University summed up this notion by saying ‘our books and manuscripts belong to no one institution but are the common property of the intellectual world and that it is our task to facilitate their use’ (Young, 1928). Likewise, because no library can ever contain the sum total of the human record, the methods and means to share resources was developed to provide access to that knowledge.

Global resource sharing has grown from a small, informal, individually negotiated request arrangement to a fully-functioning network of borrowers and lenders around the world. In the early part of the last century, international cooperation and the number of transactions processed could be measured in the hundreds. In 1926, for example, a Danish librarian reported that a total of 756 books were borrowed from Norway, Sweden, and Germany during the preceding ten-year period (Drachmann, 1928). In the same year, the Library of Congress lent approximately 3,000 items outside the District of Columbia, with a small percentage of those going to Canada, Italy, Germany and Norway (Ashley, 1928). Ten years later, the British Library lent a total of 1,141 books abroad and borrowed less than 500 during the five-year period 1931–36 (Filon, 1950). By 1950, the amount of materials lent annually to libraries outside Great Britain increased to 1,587 volumes loaned to libraries in 38 countries (Colson, 1962) and less than 50 years later, interlibrary loan transactions numbered in the millions (Mak, 2011). Additionally, by 2010, interlibrary loan transactions are measured in seconds, minutes and hours, not weeks, months and years.

Before an item can be borrowed it must first be found (Pings, 1966). Union catalogs made discovery possible, though not always easy, to locate those materials. Today WorldCat, the world’s largest but by no means only union catalog, contains more than 200 million bibliographic records and more than one billion holdings in nearly 500 languages and dialects, with more added daily. Titles and holdings are now accessible from any Internet browser. Discovery, once the greatest barrier to borrowing, is now nearly ubiquitous.

Similarly, standardized request messaging systems have made the request process quicker and easier for patrons and libraries. Developments and widespread use of document transmission software makes for fast, reliable and inexpensive delivery of copies. The development of recognized codes of practice and streamlined payment options has also resolved numerous problems associated with the borrowing and lending of library materials outside national borders.

Enormous strides have been made within the past 15 years making international interlibrary loan a ‘viable, economical and natural option’ (Miguel, 2007: 512), yet obstacles remain even as new challenges emerge. Not every attempt at global sharing of library resources has been realized. The fear of loss of or damage to library materials, along with the expense and anxiety of international shipping, is not new. It remains a powerful de-motivator to sharing for many libraries. Not every request to borrow or lend outside national borders is successful. Every day, for a variety of reasons, many of these requests fail. A plethora of rules and policies exist between institutions and countries that often make cooperation a tricky course to maneuver. Successful global resource sharing resources requires time, money, patience, perseverance and flexibility. Many places on earth lack a tradition of library cooperation and the necessary economic and technological resources to participate in international ILL and document delivery. For these countries, resource sharing has developed unevenly and may still be unfeasible for the foreseeable future.

Despite these challenges, the number of international interlibrary transactions continues to increase dramatically each year. With improved discovery tools and requesting mechanisms, it seems likely that this trend will continue. Less than 400 years after the first failed attempt at interlibrary cooperation, international borrowing and lending is recognized as an essential library service. We think M. de Peiresc would be pleased.

Highlights

1627 – Gabriel Naude proposed the creation of union catalogs with his publication Advis pour dresser une bibliothèque

1634–35 – Nicolas Claude Fabri de Periesc attempted to negotiate the exchange of two original manuscripts held in the Royal Library of Paris and the Barberini Library in Rome

1836 – U.S. National Library of Medicine founded

1850 s – first national union catalog attempted in the U.S.

1876 – American Library Association founded

1877 – Library Association founded in the United Kingdom

1890 s–1960s – La Bibliothèque Nationale de France issues national union catalog in print form

1900 – Photoduplication (Photostat) process developed in France

1908 – Society for Librarianship established in Russia

1912 – Library of Congress and New York Public Library used Photostat process

1917 – the first ALA Interlibrary Loan Code produced, adopted in 1919 and revised in 1940, 1952, 1968, 1980, 1994, 2001 and 2008

1927 – International Federation of Library Associations founded; H.W. Wilson published Union List of Serials in Libraries of the United States and Canada

1934 – first teletype network introduced in the U.S.

1936 – first IFLA interlibrary loan form appears

1946 – Canadian Library Association founded; French telex network organized

1948–1972 – Farmington Plan to acquire foreign books and pamphlets by U.S. libraries in operation

1949 – Center for Research Libraries organized

1952 – major ALA ILL Code revision and introduction of a standardized request form

1953 – Library of Congress and National Library of Medicine use fax machines to transmit copies

1959 – ALA adopted International Interlibrary Loan Procedures for United States Libraries, based on 1954 IFLA Code

1964 – telex in use by CISTI to transmit documents

1967 – Ohio College Library Center (OCLC) founded

1968 – first of 754 volumes in The National Union Catalog, Pre-1956 Imprints is published in the U.S.

1969 – Canada adopted bilingual ILL request form

1973 – British Library created under The British Library Act of 1972

1974 – Research Libraries Group (RLG) founded

1976 – major revision of U.S. Copyright Law

1977 – Washington Library Network (WLN) founded

1979 – OCLC ILL messaging subsystem introduced

1980 – RLG introduced RLIN, its union catalog

1982 – MINITEL introduced in France

1991 – RLG introduced Ariel, a document transmission software; ISO InterLibrary Loan Protocol (ISO ILL) first approved

1995 – IFLA voucher scheme introduced

1999 – WLN and RLIN merged with OCLC

2003 – RLG introduced SHARES, a standards and subscription based peer-to-peer ILL system

References

Aman, Mohammed M. Document Delivery and Interlibrary Lending in the Arab Countries. Interlending & Document Supply. 1989; 17(no. 3):84–88.

Ashley, F.W. Interlibrary Loan From the Viewpoint of the Lending Library. In: McMillen James A., ed. Selected Articles on Interlibrary Loans. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company; 1928:53–65.

Ballou, Hubbard W. Photography and the Library. Library Trends. 1956; 5(no. 2):265–293.

Borrowing Books Across the Ocean. Borrowing Books Across the Ocean. Public Libraries. 1908; 13:170–171.

Bowker, Richard R., Remarks. American Library Association: Papers and Proceedings, 31st Annual Meeting of ALA 3. 1909:156.

Campbell, Duncan, The Heritage of Books, Collecting and Libraries. China Heritage Quarterly. December 2009;(no. 20). http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/editorial.php?issue=020 [(accessed December 1, 2010)].

Chudnov, Daniel, The History of Interlibrary Loan. 2001. available at. http//:old.onebiglibrary.net/mit/web.mit.edu/ dchud/www/p2p-talk-slides/img0.html

Code of Practice for Interlibrary Loans. In: McMillen James A., ed. Selected Articles on Interlibrary Loans. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company; 1928:81–85.

Colson, John C. International Interlibrary Loans Since World War II. Library Quarterly. October 1962; 32:259–269.

Condit, Lester. Bibliography in Its Prenatal Existence. Library Quarterly. 1937; 7(4):564–576.

Coney, Donald. The Potentialities: Some Notes in Conclusion. Library Trends. 1958; 6(3):377–383.

Davis, Denise M., Library Networks, Cooperatives and Consortia: A National Survey. 2007. (accessed November 1, 2010). http://www.ala.org/ala/research/librarystats/cooperatives/lncc/Final%20report.pdf

Dewey, Melville. Inter-Library Loans. Library Notes. 1888; 3:405–407.

Drachmann, A.G. Interlibrary Loans in Continental Europe. In: McMillen James A., ed. Selected Articles on Interlibrary Loans. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company; 1928:32–37.

Fang, Conghui. The History and Development of Interlibrary Loans and Document Supply in China. Interlending & Document Supply. 2007; 35(3):145–153.

Feipel, Louis. Primitive Inter-Library Loan System. Library Journal. August 1910; 35:370.

Filon, S.P.L. International Library Loans. The Library Association Record. March 1950; 52:76–81.

Gaines, Abner J. Farmington Plan. In: Wiegand Wayne A., David Donald G., Jr., eds. Encyclopedia of Library History. New York: Garland Publishing Inc; 1994:193.

Gilmer, Lois C. Interlibrary Loan: Theory and Management. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, Inc; 1994.

Gosnell, Charles. The Collection. Library Trends. 1957; 6(1):28–34.

Gravit, Francis W. A Proposed Interlibrary Loan System in the Seventeenth Century. Library Quarterly. October 1946; 16:331–334.

Green, Samuel S. The Lending of Books to One Another By Libraries. In: McMillen James A., ed. Selected Articles on Interlibrary Loans. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company; 1928:79–81.

Hicks, F.C. Inter-Library Loans. Library Journal. February 1913; 38:67–72.

Hoare, Peter. Oxford University Libraries, U.K. In: Wiegand Wayne A., Davis Donald G., Jr., eds. Encyclopedia of Library History. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc; 1994:482–484.

Hovde, David M. International Cooperation. In: Wiegand Wayne A., Davis Donald G., Jr., eds. Encyclopedia of Library History. New York: Garland Publishing Inc; 1994:288–290.

Kilpatrick, Thomas L. Interlibrary Loan: Past, Present, Futures. In: Cargill Jennifer, Graves Diane J., eds. Advances in Library Resource Sharing. Westport, CT: Meckler; 1990:22–38.

Krym, Naomi, VanBuskirk, Mary. Resource-Sharing Roles and Responsibilities for CISTI: Change is the Constant. Interlending & Document Supply. 2001; 29(1):11–16.

Lushchik, Maria, Milson, Margit, Sikk, Maiu. Estonian Interlending and Document Supply: Historical Experience and Today’s Reality. Interlending & Document Supply. 2006; 34(1):21–23.

Mak, Collette. Resource Sharing Among ARL Libraries in the US: Thirty Five Years of Growth. Interlending & Document Supply. 2011; 39(1):26–31.

Miguel, Teresa M. Exchanging Books in Western Europe: A Brief History of International Interlibrary Loan. International Journal of Legal Information. 2007; 35(no. 3):499–513. [Winter].

Pings, Vern M. Interlibrary Loans: A Review of Library Literature, 1876–1965. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University; 1966.

Rayward, W. Boyd. Library Associations, International. In: Wiegand Wayne A., Davis Don G., Jr., eds. Encyclopedia of Library History. New York: Garland Press; 1994:342–347.

Shuh, Barbara. The Renaissance of the Interlibrary Loan Protocol Developments in Open Systems for Interlibrary Loan Message Management. Interlending & Document Supply. 1998; 26(1):25–33.

Straw, Joseph E. When the Waells Came Tumbling Down: The Development of Cooperative Service and Resource Sharing in Libraries: 1876–2002. The Reference Librarian. 2003; 40(no. 83/84):263–276.

Stuart-Stubbs, Basil. An Historical Look at Resource Sharing. Library Trends. April 1975; 23(4):649–664.

Wehefritz, Valentin. International Loan Services and Union Catalogues. Main, Germany: Vittorio Klostermann; 1974.

Wright, Walter. Interlibrary Loan: Smothered in Tradition. College and Research Libraries. October 1952; 13:333–336.

Young, M.O. Theory and Practice of Interlibrary Loans in American Libraries. In: McMillen James A., ed. Selected Articles on Interlibrary Loans. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company; 1928:13–24.