CHAPTER 5: BUSINESS CONTINUITY PROCEDURES

BC procedures were referred to by BS25999 as BCM response, and in many respects, this is what BCM is all about. The response that is executed in the event that something goes wrong, is based upon all of the analysis, preparation and planning that we have looked at so far.

The quality of the response will determine whether the impact actually sustained is within the limits that the governing body has accepted.

The requirements of the Standard are:

- An incident response structure (referred to at the beginning of Chapter 5), including communication mechanisms

- Business continuity and incident management plans

- Plans to restore business activities from temporary measures adopted.

The previous standard also specifically required that the BCM response is based on the outputs from determination of strategy, though it can probably be assumed now that to do otherwise would be so counter-intuitive that the rest of the system would be unlikely to meet the requirements of ISO22301.

The incident response structure

In a significant departure from BS25999’s approach, incident response structure is essentially a set of processes for:

- Detecting incidents

- Establishing whether their severity warrants a formal BCM response

- Activating the response, including communications

- Availability of resources to enable the response to be executed.

Command structure – teams and roles

ISO22301 deals with the make-up and activities of the response team(s) in three sub-sections (8.4.2 – 8.4.4), however, this chapter continues to address these two facets together. When, and if, it comes to certification under the Standard, there are evidence requirements within the three sub-sections relating to response structure and to business continuity plans, which are covered in detail here.

In terms of command structure, the requirements depend entirely on the size and nature of the organisation. One of the lessons learned by a major, financial services company, from the 1996 bomb in Manchester, UK, was the importance of a well-designed, well-informed and capable leadership.

A very common pitfall in this area is to simply replicate the organisation’s management structure, and, worse still, to use peoples’ day job titles within the command structure.

Roles within the command structure need, really, to reflect the nature of the situation. So, for example, ‘Team Leader’ is often a more useful title than ‘Chief Executive’, not least because, in some situations, the best person to lead the command structure might not be the Chief Executive. Similarly, the Chief Executive might be the preferred media spokesperson for the organisation, but if he or she were to move on, the Marketing Director might then become the preferred spokesperson, rather than the new Chief Executive.

The key principles behind the command structure approach are listed below.

- Decision making in a crisis is very difficult, and is probably a completely new experience for the majority of executives, as there is virtually no opportunity to practise. In such a situation, it is arguably more important than ever that, regardless of whether the organisation’s day-to-day management is team based or hierarchical, those making decisions have the benefit of contact with senior colleagues, with whom to arrive at the best decisions for the organisation.

- Decisions made in respect of one part of an organisation can have an effect on other parts of it. If the entire organisation is represented in the decision-making process, those decisions are likely to be better overall.

- In a crisis, it may be that some parts of the organisation are required to make compromises, or even sacrifices, in order that another part may continue to operate or recover. Any significant conflicts that such a decision may create are probably best handled at the most senior level, so that implementation of such decisions can be rapid, in what is bound to be a very fast-moving environment.

Teams and structure

Many organisations need no more than a single team, comprising members whose roles reflect the various departments or divisions that execute the organisation’s critical activities, and those that provide support services to those departments, such as IT, facilities management, human resources management, industrial services, health and safety, security, and so on.

This may work well for smaller organisations based on a single site, but, as organisations get larger in terms of corporate structure, numbers of staff and location, the need for a structure of teams is likely to emerge.

In order to establish what sort of team structure might be required, it is worth looking at what tasks members of these teams actually need to undertake.

The principal tasks include:

- Collecting information about the incident, impacts and the progress of recovery activities

- Taking decisions

- Implementing decisions

- Directing critical activities in recovery

- Communicating, both internally and externally.

A single team is probably desirable, but each member of that team will need direct communications with at least one other member of the relevant department, or division, who can execute decisions made by the team and report back on progress. Depending upon the size of the organisation, that person might be the leader of another team, and that team might, in its turn, need to convene, in order to agree decisions in a similar way to the first team. This could be the case if decisions taken by the first team can be implemented in a number of ways; it depends on how ‘strategic’ those decisions are.

A two-tier structure thus emerges, though this should be based upon need, rather than anything else; there is no merit in two organisations trying to make decisions that subsequently conflict with each other.

One of the more popular approaches is the ‘Gold, Silver and Bronze’ structure, adopted by the emergency services in the UK for civil emergency management, though this title is really little more than a familiar labelling of a three-tier arrangement.

Example 6 shows how this might be applied in other settings. It relates to a medium-large company engaged in an information-processing type of business, comprising a number of subsidiary companies, operating at a variety of locations.

Example 6: Gold, Silver and Bronze

This company comprises three or four subsidiaries of a holding company, which, itself, takes a minimal form. The Group Chief Executive is also Chief Executive of the largest subsidiary, and the other subsidiaries have their own Chief Executives. The group’s companies are generally distributed separately, so that most of its offices are dedicated to one company or another, but the group will, sensibly, make use of these offices in the event that one of them, particularly the largest, is unavailable. Each subsidiary could simply have its own single team, but there are scenarios which would require a group level response, such as pandemic influenza, or a major reputational incident, so there is a Gold team which operates at group level, as well as a Silver team for each subsidiary. The size of the subsidiaries is such that Bronze teams for each of the support functions, for example, are not necessary, and the Silver team will utilise the existing management in those areas to execute its decisions. The group’s IT systems are managed at group level, providing a service to each of the subsidiaries, and there is a Bronze team responsible for this part of the response and recovery process …

… The Bronze IT team has ‘relationships’ with the Gold team and with each of the Silver teams. If the incident is confined to one location, the Gold team may not be convened, unless, perhaps, there were a fatality, or something of that severity, and the Bronze IT team would simply work with the relevant Silver team to restore critical activities. If there were a pandemic or some scenario likely to affect multiple subsidiaries, the Gold team would be convened and take the majority of the decisions.

This mechanism is written into the BCP, so that it is clear how the structure will work in a variety of situations.

In other organisations, the Gold team may need to take all the strategic decisions, such as what stories to release to the media, or whether to suspend operations. This leaves the Silver team to get on with the job of restoring critical activities.

Roles

Put simply, the roles within a team need to reflect the sort of tasks that are likely to be required. Appendix 4 provides an example of a Crisis Management Team and its roles.

Collecting information

The command team(s) cannot take effective decisions if they do not know what is actually going on. In order to establish the nature and extent of an incident, it may be appropriate to appoint one or more roles tasked with reporting to the command structure.

An important planning consideration for roles such as this, is the provision of appropriate communication facilities and channels. These might include mobile telephones, two-way radios, and forms designed to prompt the collection of relevant information.

Communicating with stakeholders

Telling people what is going on is an obvious thing to do, when one considers incident management in the cold light of day. In the event of a real incident, however, people may be under such pressure that informing others of the situation starts to get forgotten.

An obvious way of addressing this is to include, in the command structure, at least one role focused almost entirely on external communications.

Team resilience – deputies

In day-to-day situations, people in decision-making roles may, from time to time, be absent. It is not practical, in a crisis situation, to wait for that person to return, and it is unlikely that the sort of control and decision making required can be achieved remotely, even using such facilities as video conferencing.

An important feature of the command structure is deputisation. Some roles may require more than one deputy, particularly where the nominees for those roles habitually travel away from the operational base(s).

It may be natural for the Chief Executive or Managing Director to take major decisions on responding to a crisis, so, in identifying deputies for command structure roles, it is critical to ensure that these deputies would be capable of leading and taking decisions, or of simply executing the tasks that might be required.

As we shall see later, exercising is a key factor in the success of the command structure. As well as reading a description of what they would have to do, the capability of people who would be expected to perform roles in the command structure will be enhanced if they have the opportunity to practise it on a reasonably, regular basis.

Triggering the BCM response – activation

The command structure should be the means by which the BCM response is activated, and it is important to identify who has the authority to do that.

This would usually be the leader of the command structure or crisis management team, or it might be someone more senior, depending upon how the teams and roles were structured.

Typically, the activation authority would formally end the business continuity phase and stand the command structure down once stable interim operations, or whatever level of recovery is stipulated in the plan, had been achieved.

The Standard requires the following:

An impact threshold that justifies a formal response – this could simply be a descriptive narrative providing guidance to anyone authorised to initiate, such as:

‘The command team leader may initiate a formal response when any incident or situation, in his/her judgement, is likely to result in operational interruption of half a day or more, or an equivalent impact according to the impact table within the BIA.’

- Assessment of the nature and extent of an incident – in many cases this can quite easily be incorporated in the statement above.

- Activation of the response – again, easily covered by the above statement.

- Processes and procedures for activation – these would normally be an integral part of a business continuity plan, but may, if preferred, be a separate document, or set of documents.

- Arrangements for communication with interested parties, authorities and media – again these are typically embodied in a business continuity plan.

Wherever these arrangements exist, their existence would normally mean that the specific requirements of the Standard are met, however, for certification purposes, it would make sense to record against the Standard, where in the management system’s documentation, specific requirements are placed.

Business continuity planning

The business continuity plan, the BCP, is arguably the ultimate deliverable in a BCM project. It provides the basis for the command structure’s decision making, and therefore, how the organisation responds to, and recovers from, the incident or interruption.

As we have seen already, the BCP should be based on the organisation’s objectives, the RTOs, and upon valid assumptions regarding the availability of resources with which critical activities may be recovered.

For this reason, business continuity planning comes towards the end of the BCM development project, rather like an executive summary.

Policy, strategy and objectives have all been dealt with elsewhere in the BCMS, so these are things that really do not need to be in the BCP, which should be telling the organisation’s command structure how to respond to the situation it finds itself in, and how to recover from it.

A BCP can be in a variety of formats. To be of practical value, though, it should be as simple as possible. In a fast-moving and stressful situation, even the most rehearsed and experienced team should not be concerned with how or why the BCMS has been developed, or, indeed, that it is based upon the principles of ISO22301!

Master plan

Regardless of the nature of an incident, the organisation’s recovery objectives should be the same, and should form a focal point in the master plan. Equally, the command structure, whilst it should be capable of dealing with a wide variety of different scenarios, should be based upon a core team. An effective master plan is likely to include the sections below.

Summary

A clear statement setting out the purpose of the BCP, that it forms the basis for the command team, or structure, to make decisions and lead response and recovery activities, and the circumstances and scope under which it should be used or followed.

Activation

A statement of who is authorised to activate the BCP, effectively triggering the BCM response. As we have seen, this is likely to be the leader of the command structure or team, and should include one or, preferably, more than one, deputy. The master plan, like everything else in the BCMS, will be subject to regular review and updating, so stating the names of the individuals who are authorised to activate the plan is a sensible idea, eliminating ambiguity in what could well be a very, stressful situation.

Lessons have been learned by many organisations faced with a major incident or crisis, where there were serious delays in triggering the BCM response, because it was not possible to contact the one person who could authorise activation of the plan.

Command location

Similarly, lessons have also been learned by some organisations which wasted a lot of valuable time trying to decide how and where to mobilise their command team.

It is not difficult to work out, and decide, a number of locations where the command team(s) could be based. The choice of location should take into account:

- Availability 24-hours a day, seven days a week

- Suitability for lengthy, group-working sessions

- Communications:

- Land lines

- Mobile phone signal(s)

- Internet services

- Telephones and fax machines

- Distance and travel time from the site(s) in question

- Availability of rest and catering facilities

- Permanent, secure storage facilities for ‘battle box’ and similar essential items.

For some scenarios, such as pandemic flu, the logical command location is often the organisation’s headquarters, and this should be included in the list of command locations, if appropriate, as should others which would not be affected by site-specific incidents, such as fire, flood or explosion.

If a command location is owned by a third party, there should be adequate assurance and knowledge that the location is likely to be available, with suitable alternatives should this prove not to be the case. One local hotel, for example, with no alternative location, is unlikely to be sufficiently robust.

Command structure

Covered earlier in this chapter, the master plan is a good place to set out details of the command structure, team or teams. Detailed lists of duties and responsibilities, should they be necessary, are probably best attached as appendices, so that the plan remains concise and, therefore, highly practical.

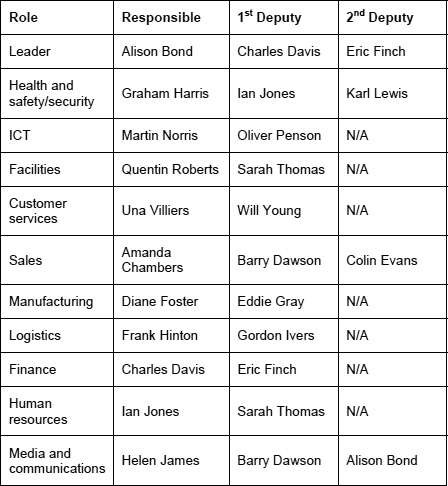

For each team, a list of the roles, together with the names of the person assigned to that role and of the deputies, should provide a sufficient level of detail for the majority of organisations, as in Figure 23.

Figure 23: A command team

Priorities and objectives

The organisation’s recovery objectives have been established through the BIA, and should be stated here. It may also be appropriate to state other objectives and priorities, such as:

- Personal safety – that the safety of all people will come before the recovery of business activities, or the protection of property. ISO22301 states that life safety should be the first priority in incident response.

- Welfare – that the organisation will treat the welfare of all its staff and, possibly, any visitors directly affected by the incident, as a priority, and will, or may, provide resources to support this.

- Reputation – whilst it may seem obvious that any organisation needs to recover its critical and other activities, as soon as possible, it may, in some cases, be even more important that actions are taken to protect the organisation’s reputation through media statements, PR activity, person-to-person communications, or the like.

- Security – some organisations may be exposed, in certain circumstances, to attacks on property, in such forms as:

- Looting

- Fraud

- Money laundering

- Vandalism

- Theft of mail or goods in transit.

These priorities should be articulated in the master plan, as well as being included in more detailed plans.

Scenario plans

In the earlier days of business continuity, many practitioners suggested that, because recovery priorities should be the same, regardless of the nature of the interruption, scenario-based plans were inappropriate and represented an unnecessary duplication of information. Nowadays, however, the range of potential situations that most organisations face is so broad, that to have one plan that deals with everything is usually completely impractical.

Let us consider two examples: a premises-related incident, such as a major fire, and pandemic flu.

A major fire is more likely to occur at night, or when the premises are empty. In 2005, deaths caused by fires in buildings other than dwellings, were less than one per 1,000 fires, and non-fatal casualties were only 40 per 1,000 fires (Fire Statistics, United Kingdom, 2005 Department for Communities and Local Government: London, March 2007). The emphasis, therefore, must be on recovering critical activities as quickly as possible, predicated upon the likely availability of the organisation’s staff.

In the case of pandemic flu, on the other hand, it will be the people who are unavailable, and so the response cannot generally be about restoring activities as quickly as possible.

Typically, scenario plans work well as a subset of the master plan. They enable the command teams, or structure, to focus on the type of response required for the scenario in question, without the unnecessary confusion of responses to other, quite different, scenarios.

Depending on what the organisation does, the range of scenarios might include:

- Premises incidents – including fire, flood, explosion and structural damage.

- Denial of access – where systems in the premises may still be operational, but, for safety or security reasons, people are not allowed in, or near, the premises.

- Resource failures – typically including IT and telecommunications, as well as utilities, supplies, transport and, perhaps, people.

- Malicious acts – including terrorism-related incidents, sabotage, breaches in information and physical security.

- Pandemic – whilst this may fall into the resource failures (people) category, there are some unique response actions likely to be required in the event of escalating World Health Organisation (WHO) pandemic alert phases.

- Environmental contamination.

- Reputational incidents.

The operational risk assessment (see Chapter 3) should identify the full range of interruption scenarios for each organisation. These should then be transferred into the BCM response phase of the programme.

Recovery plans

The master plan sets out, amongst other things, the RTO for many of the organisation’s activities, as well as the minimum activity level in each case.

An organisation conducting only one or two activities could feasibly include the details for how those activities are to be recovered, but it is likely that, in the majority of cases, individual activity or process recovery plans will be required.

The activity recovery plans will typically set out a short narrative of how and where the activity should be recovered, and specific details, including:

- Primary and secondary (if planned) locations

- DR resources and how they are invoked

- Other resources, such as those normally used by other staff, and how they are obtained

- Contingencies for lower-than-expected levels of resource availability, including people

- Methods of communication

- Reporting requirements (to the command structure)

- Interim or alternative arrangements for travel, accommodation and shift patterns

- Reconciliation of information in use before the interruption with that which has been restored

- Dealing with backlogs of work.

These recovery plans should generally be ‘owned’ by the person responsible for managing, or leading the activity on a day-to-day basis, maximising the likelihood that they will actually work when used for real.

Other plan components

Effective execution of response and recovery tasks is also likely to be enhanced through the use of additional components, which may include those below.

Procedures

Procedures are essential for a variety of tasks that are likely to be required during the entire, business continuity phase. They will almost certainly be required for the invocation of DR and other resources, providing important information about how to activate or invoke these resources, how they should be used, and what levels of performance, or activity, should be expected.

Procedures are also likely to be of great value for other activities that are not usually undertaken, such as communication cascades, media handling, infection control, casualty management, security, and many more.

Documented procedures will be required for the recovery, or restoration, of supporting resources including DR; for the recovery of critical and other activities; and for any other detailed tasks that might be required, such as arranging alternative supplies to customers.

Incident log

The value of keeping a reasonably, comprehensive record of an incident cannot be understated. BCM is an important component in corporate governance, as it provides some assurance that the organisation has taken appropriate steps to control, and minimise, the risks associated with, inter alia, business interruption. Similarly, any investigation into, or scrutiny of, the handling of an incident and recovery from it, will require the best, possible evidence that the organisation did, in fact, use its BC plan.

The inclusion of blank incident log sheets in the BCM system should ensure that the right information is recorded and that time is not wasted. It should also ensure that there is no failure to record early events because of the time taken before someone realised the need to keep a record.

Internal communication

In many organisations, there is likely to be the need to inform staff of any incident, or similar situation, as quickly as possible, without occupying significant amounts of time for members of the command structure. The more traditional communication cascade, or calling tree approach, if well designed, can provide a good level of assurance that all the necessary people can be informed.

Some larger organisations are beginning to use the emerging notification services, of which there appears to be a growing number. With the very widespread use of ‘smartphones’ and other mobile devices, the use of these systems is becoming increasingly viable, and assuming that costs continue to fall, it can only be a matter of time before they are used in the majority of cases.

However, for the time being, the traditional methods remain of value to many organisations, and whilst a cascade system need not necessarily follow the organisation’s management structure, there are obvious benefits in its doing so, as far as is practicable. Many organisational structures, however, do not make the best cascade structures, as they may involve senior people (who are more likely to be members of the command structure) in contacting a large number of people, when they may be urgently needed for leadership tasks.

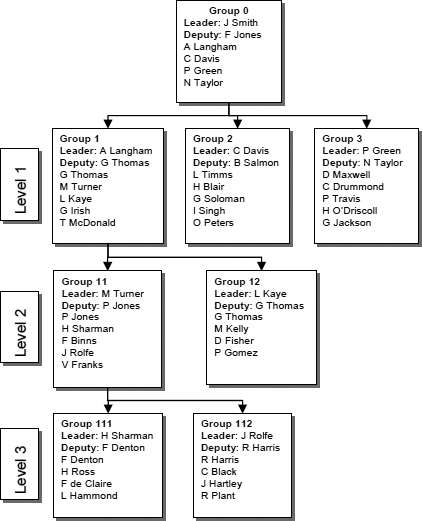

A sensible approach is to start with the existing management structure. In Figure 24, a conveniently-balanced management structure provides the basis for an equally, well-balanced cascade system. Group 0 is effectively at the command team level. Some, or all, of its members are themselves leaders of Level 1 groups. Two members of Group 1 (Level 1) are leaders of Level 2 groups, and two members of Group 11 (Level 2) are leaders of Level 3 groups.

This example shows one deputy for every group, though, in some circumstances, a second deputy may be appropriate.

In larger organisations, the cascade structure may be very complex; individuals really only need to see the people that they are required to contact, including deputies, in the event that the leader of a group cannot be contacted.

A simple cascade, like that in Figure 24, is easy to use in this form, though it would, of course, require some contact information for each person. For much bigger structures, a different approach is likely to be needed. Appendix 5 contains an example of a spreadsheet-based cascade list, which is almost infinitely scalable.

The cascade system should also take into account the need to provide feedback to the command structure, and to request further information, or to request authority, for particular actions that might be appropriate at the time.

With this in mind, the leader of a cascade group cannot simply contact everyone on their list and then switch their phone off. Their role as a cascade leader may well need to include being able to receive calls from ‘downstream’.

Figure 24:A cascade system

Contact data

When asked about contact data that might be needed in a crisis, most people simply hold up their mobile phone. This may well be a sensible component of the BCP, and provide the ability for command-structure members to contact third parties, such as recovery service providers. However, in order that a proper level of assurance can be provided as to the completeness and adequacy of the BCMS, and the BCP in particular, it makes sense, wherever possible, to hold a central, contact database of some sort.

This, of course, brings with it the potential problem of currency; keeping the information up to date. In addition, since many organisations today keep their master contact information in an IT network, which may well not be available in a crisis, an independent source of this information is highly desirable.

Categories within this contact data set may include:

- Stakeholders

- Customers or clients

- Suppliers

- Bankers, accountants and lawyers

- Insurers and loss adjusters

- Response and recovery service and resource providers

- Media contacts.

How the plan works

In a real crisis, the command team has to take decisions and execute them, usually very quickly. These decisions need to be informed, not only by the situation at the time, but also by a lot of common sense that has been fully thought through at a time when there was not a crisis.

The plan may be a single document that aims to deal with the majority of situations, or a multilevel system comprising a master plan and scenario plans. In either case, it should act as a set of decision-support tools identifying the overall theme of the response, or the approach to it, and likely actions that should be taken in reply to certain trigger events or times.

The plan should go on to identify specific procedures for tasks that would not typically be undertaken on a regular basis. These include the invocation of DR and other resources, communications with staff and stakeholders about the incident, the recording of key information about what happened, and the decisions taken by the command team(s), and the results of those decisions.

The command team(s) would generally work as a group, referring to the various levels of planning documentation, taking decisions, and then executing them through appropriate communication channels available at the time.

The typical evolution of a crisis is likely to include a number of phases, as in Figure 25.

During the incident response phase, a clear, concise plan is essential, together with more detailed procedures, or instructions, for executing decisions taken by the command team or structure. Movement into the recovery phase is likely to be characterised by the successful accounting for all people, and the satisfactory management of any casualties or fatalities. In situations involving contamination, such as CBRN, this phase is likely to continue until the safety of all staff and visitors has been assured.

The recovery phase is likely to follow the incident response phase immediately, but, in some situations, there could well be an overlap between the two. The command team(s), as in any crisis situation, will need to use their judgement regarding the commencement of recovery tasks before all health, safety and welfare issues have been fully resolved.

The recovery phase is primarily focused upon the deployment and invocation of contingency arrangements and alternative ways of working – the recovery of critical activities. Whilst, for many, this may mean picking up where they were before the incident, and continuing to do what they would normally do on a daily basis, the effects of an incident, even one that appears fairly minor, should not be underestimated.

The use of welfare resources, including counselling or flexible working arrangements, may well be appropriate. Documented recovery plans, with related procedures, will be important, particularly where some individuals are less capable of executing their normal, daily tasks than they would otherwise be.

The objective of most BCPs is likely to be to return much of the organisation to a stable, interim operational state, as quickly as possible, and to protect the organisation’s brand and reputation. The latter will be achieved significantly through effective communication with clients, or customers, and any other influencers, including the media.

The media-handling component which is likely to be present in the incident response phase, will, therefore, probably continue into the recovery phase, perhaps shifting from a reactive to a proactive stance.

The continuity phase represents stability of the interim operational state, and may continue for some considerable time, depending on the nature of the incident and the organisation’s infrastructure.

Figure 25: Crisis evolution

Multilevel (organisational) plans

In larger organisations where there are multiple locations, entities, business units, companies, and so on, a multilevel plan structure may well be appropriate.

Such a structure will depend entirely upon the nature of the organisation in question, but the guidelines below should always be borne in mind:

- Less is more – the fewer plans, the better.

- Many incidents are location specific, and are best dealt with by a location-based plan, often regardless of the corporate structure within the location.

- Major issues that may affect the organisation’s brand may be best handled at the highest level, with two, or even more, plans operating simultaneously.

- The command structure may change as higher, or lower, level plans are activated, and deactivated.

In practice, it is relatively difficult to achieve complete synchronisation between plans at different levels. What is often most important is that the rules for activation do not force a number of competing plans to be operating at the same time.

Ending the business continuity phase

It may seem obvious that, when the organisation or its component parts have reached an acceptable level of operational stability, the BCP and command structure should, at some point, be stood down.

In longer-term situations, where return to BaU is not possible, people get used to working in a different way, and the value of keeping the command structure in place will begin to diminish. In this type of situation, attention must soon turn to planning the return to whatever level of normality is possible.

In other situations, interim working may last for only a few weeks, or even days, and here it may well be appropriate to keep the command structure in place until BaU has been achieved and stabilised.

The BCP should refer to ending the business continuity phase, including the communications which should accompany that action. Stakeholders, customers, clients and staff will need to know when the whole thing is over and normal service can be expected.

In addition to this, many organisations may well be able to benefit from PR at this stage. Positive stories about organisations that survive a major interruption unscathed are quite rare, and if clients’ and customers’ expectations have been met, or even exceeded during the business continuity phase, there will be much to celebrate and capitalise upon.

Recovery

ISO22301 introduces a new requirement; there should be a plan to recover from the temporary arrangements adopted. The Standard is actually quite un-specific here; it doesn’t require plans for returning to the business as usual state, nor does it suggest returning to the premises or other location affected by an incident. What it seems to be getting at is that there should be a way of resuming activities to the pre-incident level, and there are clearly a number of ways of meeting this requirement.

A procedure is whatever the organisation decides it should be; it could be anything between specific instructions for setting up parallel operations in another location, and a broad statement that the organisation will identify the best way to resume what it was doing before the incident, perhaps by way of a project.

The key issue here is that the starting point is somewhat unknown. What any organisation decides to do about longer term resumption of activities can vary widely, dependent upon the situation at the time.

It is unlikely that detailed plans to return to the pre-incident location(s) are worthwhile, not least because that may not be possible, and for a variety of reasons.

In larger, multi-site, organisations, a possible strategy post-incident is simply not to re-instate a particular operation, instead transferring its output to another unit. In others, it may make more sense to re-instate activities, but the way of doing that is likely to depend upon what has actually happened.

Ultimately, it is for the organisation to decide how much of a plan it can draw up for this requirement – the main gist of the Standard is to establish how customers’ requirements or expectations would be met; that they may have put up with lower levels of output or supply, but there needs to be an understood way of meeting their longer term requirements.