| 6. | |

| THE GREAT TAKE-OFF |

Up to the year 1450, all European books had been handwritten, and it had typically taken a monk or a scribe up to a year to produce a single book. For this work they would normally charge a florin per five pages - corresponding to approximately 1,500 dollars today - which meant that a book could easily cost the equivalent of 100,000 dollars or more in modern money.

This changed, however, when, in 1450, German inventor and publisher Johannes Gutenberg launched his printing press. Even though he never made any money out of it (he went bankrupt, as previously mentioned), his invention eventually became a huge success, and was soon copied everywhere (our alchemist’s fallacy in action). As an example, the printing house Ripoli would, in year 1483, print no fewer than 1,025 copies of Plato Dialoges, an achievement that 33 years earlier would have required at least1,000 man-years of work and cost the equivalent of perhaps $100 million in present money.

In year 1500 - just 50 years after Gutenberg had invented his machine - Europe as a whole had no fewer than 220 book printers, which produced a total of eight million books, ranging from specialist titles to popular pocket-size books.60

That we continuously learn theories and information from new books during the course of our lifetimes may seem obvious to any modern person but, in past communities, the prevailing thought would have been that there was only one good ideas system and that all others must therefore be treacherous. However, with the development of cheap books, new ideas started spreading like wildfire.

Other than in China and Korea (which both invented printing presses before Gutenberg) there had not existed reasonably large, popular book markets anywhere else in the world. What was special about the European print book market was, first, that it came at the time of the Renaissance, where people had already become more receptive to free thinking and, second, the book market was subject to fierce competition – book printers could only thrive if they constantly managed to be first with the latest publication. China, on the other hand, had been a centrally-controlled society, where printers largely produced what the state demanded.

European book mania became one of the driving forces behind the Age of Enlightenment.62 The basic concept of the enlightenment was that science, systematic doubt, rationality, cosmopolitanism and individualism should replace superstition, irrationality, theological dogma, insularity and group-think. This movement was partly triggered by Copernicus’ aforementioned work from 1543, which, paradoxically, was commissioned by the otherwise conservative Catholic Church.

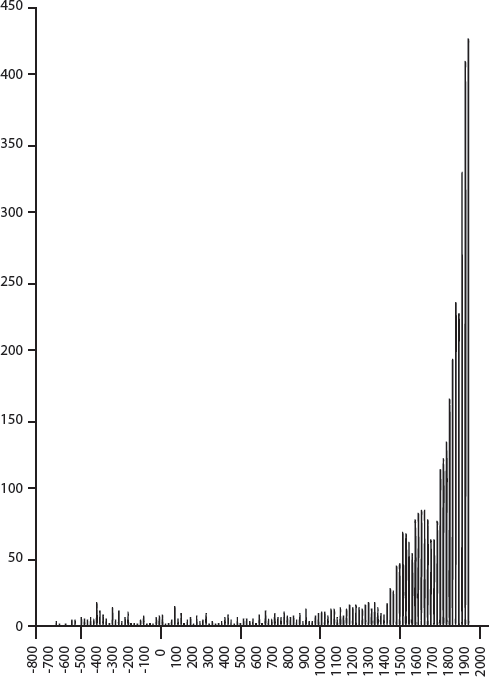

EUROPE’S BOOK PRODUCTION YEAR 600-1800. IT IS EASY TO SPOT THE ENORMOUS CHANGE AS BOOK PRODUCTION CHANGES FROM COPYING-BY-HAND TO PRINTING.61

While the Enlightenment largely grew out of Northern Italy and France, it quickly spread across the Continent and to the US. Its main thinkers included names we have already heard: Montesquieu (separation of powers), John Locke (personal freedom, equality and protection of private property), Thomas Hobbes (the social contract), Adam Smith (free trade) and Edward Gibbon (author of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire). However, there were many others, including Frenchmen Pierre Bayle, Voltaire, Denis Diderot, Anne-Robert-Turgot, René Descartes and Nicolas de Condorcet; Dutchman Baruch Spinoza; Germans Baron d’Holbach, Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottfried von Herder; Britons Francis Bacon, Francis Hutcheson, David Hume and Isaac Newton; and American Benjamin Franklin. Such famous thinkers were supported by considerable networks of underground pampletheers and printers, who distributed forbidden bestsellers, in which one particularly courageous swiss printing house, Société typographique de Neuchâtel, came to play a pivotal role.

As well as making people more open, rational and individualistic, the Enlightenment replaced fatalism with inginuity. Before enlightenment, when people experienced accidents, losses and tragedies such as lost wars or children dying from infections, they would often see the explanation as God’s punishent for their sins, which should not be questioned. However, with enlightenment they became more likely to ask questions such as: “What was wrong with our battle strategy?”, “What causes these diseases?” or “How can we prevent this problem in the future?” When vaccinations were invented, some religious fundamentalists rejected it as interference in God’s ways, but most believed that, while one should not question the ways of the Lord, it was worth noting that he seemed more likely to help those who helped themselves.

Enlightenment did something else: because of its systematic approach to seeking truth, it made it possible to settle discussions simply by testing emperically who was right. It was thus a peace-maker.

There was a final important element of the Enlightenment: it was optimistic. Most of its supporters thought mankind had real scope for making the world better, and many of them envisaged a much improved future. For instance, in 1795, the aforementioned Enlightenment thinker Nicolas de Condorcet predicted that science and technology would bring human progress without limit. He also foresaw that the New World would proclaim independence from Europe and then have tremendous success through introduction of European technologies. Slavery would be abolished, he said, and people would gain contraceptive technology and more free time. Furthermore, like Benjamin Franklin, he predicted that agricultural productivity would soar.63

The Enlightenment movement was supported by an increasing number of scientists who,in book after book, described, in parts, how the world worked, and also how people should think about it. These included the physician Andreas Vesalius who published De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (which translates as “On the fabric of the human body in seven books”), which described the human anatomy – one step of many designed to deconstruct things and study their constituent parts. There was also Kepler, who wrested astronomy out of the hands of the superstitious astrologers and Galileo, who explained why the Earth was not the centre of the universe (and why the sky was not a black ball with holes in, as many had otherwise assumed). And there was Newton, who came up with his laws of gravity and motion as well as the discovery that light comprised the particles we now call photons.

The thoughts that had been revived during the early Renaissance (freedom, rule of law, science, logic and religious tolerance) were now given further tailwind. Likewise, the idea of democracy gained evermore traction. The early interpretation was that those who paid taxes to the state should have a say in how their money was spent. This meant, in practice, that only land-owning men could vote. Later came the argument that if you sent people to war, they should also have a vote, whether or not they were landowners. That sounded fair enough, but some disagreed, because the decisive military technology was the cavalry charge, which tended to be performed by knights, who were either influential and rich landowners or the sons of such landowners. However, the invention of powerful guns and cannons made foot soldiers much more important than previously, so their demands for democracy gained weight. Finally, as rule of law became more common, people began to demand a say in how these laws were written, if they were to be expected to abide by them.

The combination of greater knowledge, democracy and tolerance now made it more common for people to meet in salons, debate clubs and coffee houses to debates the meaning of life, the organization of society or the latest technological and scientific discoveries. It was also during this period that scientists began holding public lectures about, for example, physics and chemistry, and these sessions were often attended by hundreds of listeners of all ages (yes, this was before television). This was also the age where writers and poets such as Goethe and Schiller, as well as musicians including Bach, Haydn and Mozart, stirred people’s emotions and where social commentators and philosophers such as Francis Bacon changed their world views. Bacon argued for example, like many of the ancient Greeks, that people should systematically use observation and controlled experiments to gain an understanding of the world.

With the new urge to find better answers to age-old questions came, of course, an increased tendency to ask new questions, and one of these was how the world looked behind the horizon.

Good question. On August 3, 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed out from the small Spanish port of Palos de la Frontera between Gibraltar and Portugal to seek part of the answer.64 His mission was to circle the Earth to find a shorter trade route across the sea to Asia.

Columbus had long been fascinated by the idea of sailing to Asia. Over the centuries leading up to his adventure, Europe had, in particular, imported silk, spices and porcelain from Asia. These had been transported via the socalled Silk Road, where items were moved laboriously via various combinations of horses, donkeys, camels and boats. When these goods finally reached European markets, they were obviously vastly expensive due to costs accumulated en route. But it had grown even worse; after the Ottoman Empire had conquered the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) the Silk Road had been largely blocked. Columbus, therefore, smelled a huge business opportunity if he could open an alternative route by sailing West.

So the incentive was there, and the idea of visiting the Far East wasn’t a new one. For instance, Giovanni de Plano Carpini travelled, in 1241-1247, over land to Mongolia and managed, sensationally, to return alive, as did the Russians Yaroslav, Alexander and Andrey Vladimir later. Frenchman André de Longjumeau and Belgian William of Rubruck had also both travelled to China, but the most famous of the explorers had been Marco Polo, who sailed to Asia between 1264 and 1295, where he visited China and other places.

MARCO POLO’S TRAVELS TO CHINA, WHICH PROBABLY TOOK PLACE FROM 1264 TO 1269 AND FROM 1271 TO 1295 RESPECTIVELY.65

Columbus’ expedition wasn’t without its problems and he lost one of his three ships. But he did make it back in 1493 and announced that he had indeed found the sea route to Asia.

Actually he hadn’t, because what he discovered was America, but no one knew that at the time and the discovery was exciting anyway. The story soon spread like wildfire across Europe, but the Spanish royal family was the first to pick up the opportunity, so six months later, on September 24th 1493, Columbus again set sail for the new land, this time with no fewer than 17 ships and 1,200 men.66

The age in which civilizations set sail and discovered the world could have been led by China and started after Zheng He’s expeditions between 1405 and 1433 but they didn’t because it was intentionally ceased. Instead, it was Colombus’ expeditions that came to mark the beginning of what we now call the Age of Discovery.

This was period of frantic activity. In 1497, four years after the beginning of Columbus’ second voyage, Italian Giovanni Caboto was hired by the British king Henry VII to sail out with one ship and 18 men to find a northern passage to Asia. He later returned and reported triumphantly that he had reached Northern Asia via the North Atlantic. This was actually also inaccurate, because it was probably either Newfoundland in Eastern Canada or the state of Maine in the northern US that he had found.

BETWEEN 1492 AND 1500 COLUMBUS MADE FOUR EXPEDITIONS TO AMERICA BUT REMAINED CONVINCED, UNTIL HIS DEATH THAT IT WAS ASIA HE HAD VISITED.67

This was now turning into a competitive race and the same year, Portuguese Vasco da Gama set sail in a 27 metre-long ship, accompanied by three other vessels, to find another way to Asia, but this time by going south of Africa. This worked, and he reached India in May 1498.

The key motivation for these people was to enrich themselves, which tended to work fairly well. For instance, da Gamas’ fleet returned home with a cargo that financed the cost of the trip 60 times over. (That’s what you call a 60x return in modern venture capital lingo, and the internal rate of return, or IRR as the venture capitalists call it, could have been around something like 3,000% (2x return and 10% IRR is now considered fair and 20% IRR is good).

Money, money, money!

The English, who had been behind in the early stages of this land-grab, also liked money. In 1508 they sent an expedition to North America, which led them up the Hudson River and through most of the Northwest Passage north of Canada. Three years later, in 1511, a Portuguese citizen named Fernão Pires de Andrade captured the city of Malacca in Malaysia, after which he headed to China and planted the Portuguese flag close to - or perhaps within – what is currently known as Hong Kong.

Just two years later, in 1513, a Spanish expeditionary force climbed over a mountain range in Colombia and discovered, to their astonishment, another wide ocean, which told them that what they had thought was Asia had been, in fact, an entirely different continent. It turned out that there was plenty of gold and silver there so, six years later in 1519, the Spanish conquest of much of South- and Central America began - an extreme story which we shall revisit later.

As time passed, more and more Western European nations joined the scene and, from 1602, the Netherlands began colonizing Sri Lanka, parts of India and Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, parts of the South American east coast and enclaves on the east coast of Africa and in the US, while Denmark, Germany and Belgium also established colonies.

These Western expeditions and conquests provided a number of new commodities, out of which two probably played a very special role: tea and coffee. It appears, from old records, that Western Europeans well into the Middle Ages, were generally heavy drinkers, and records show, for instance, that, in the 15th century the average English adult, male or female, drank approximately. 4.5 litres of beer a day. That’s 9 litres daily for a couple, on average. However, with the introduction of tea and coffee, people probably began to sober up somewhat, which would have made their discussions of politics and science more constructive.68

Events took a new turn at the beginning of the 18th century, where an improved melting process was developed for making steel, which was followed by invention of the flying shuttle for textile production (1733), the Bridgewater Channel (1761), the Spinning Jenny (1761), and the steam engine (1769). This was the beginning of the Industrial Age, which began along the Clyde River in Scotland, then spread to England and beyond. It facilitated an acceleration of urbanization while giving Europeans a wealth of mass-produced objects for global trade.69

The Industrial Revolution was followed by the Women’s Liberation Movement, which demanded equal contract rights, marriage rights, parenting rights, voting rights and property rights for women. After that came the IT revolution, the biotech revolution and the crowdsourcing revolution, all of which we shall study in more detail later.

When you really think about it, there’s something utterly bizarre about what happened in Western Europe from 1450 until today, but it is even more amazing to think about the events that took place between 1450 and 1500. During these decades, the lust for learning, the “book bulimia”, the race for space and the grab for gold were all completely frantic, as people suddenly saw countless opportunities for discovery, adventure, development and prosperity everywhere that they hadn’t spotted before.

EUROPEAN-DOMINATED AREAS IN 1900. IN ADDITION TO CONTROLLING SOME 85% OF ALL THE WORLDS’ LANDMASS AND APPROXIMATELY 85% OF ITS ECONOMY, THE EUROPEANS AND THEIR DESCENDANTS ALSO RULED THE GLOBAL SEAS ALMOST UNCHALLENGED.70

It becomes even more bizarre when we consider the fact that it was not the whole of Europe that was responsible for this gigantic endeavour, but largely Western Europe, whose population had grown from about 20 million when the Roman Empire fell to approximately 45 million in year 1500.70 This population constituted just 10% of the global population and, before the start of the colonial era, controlled barely 2% of Earth’s landmasses. Seen from a global perspective, it was a small population inhabiting a tiny stretch of land. And yet, Western Europeans went out and conquered most of the world’s landmasses and gained 100% control of the seas.

It also adds to the story that, in year 1000, the Western European GDP per capita was probably only on par with the South- and Central Americas, which then was only inhabited by Indians. And Western Europeans were probably approximately 5% poorer than the Japanese and, yes, Africans, and (it is assumed) approximately 10% lower than that of non-Japanese Asians. And yet, some 500 years later,these Western Europeans would stream out from their tiny lands and conquer most land in these places.

ESTIMATES OF GDP PER CAPITA IN DIFFERENT PARTS OF THE WORLD IN THE YEAR 1000, YEAR 1500 AND YEAR 1913, RESPECTIVELY (1913 IS THE YEAR IN WHICH THE BRITISH EMPIRE PEAKED). NOTE THAT WESTERN EUROPEANS IN THE YEAR 1000 ARE ESTIMATED TO HAVE BEEN POORER THAN BOTH ASIANS AND AFRICANS.71

Just how relatively undeveloped Europeans had been in year 1000 is underlined by the fact that, in 600 BC, Arab Muslims had conquered previously Christian territories in North Africa, Syria, Palestine, Portugal and most of Spain. In the year 732, there had actually been a Muslim army camped just 70 km from Paris, and Muslims possessed a sizeable proportion of Provence and sacked Rome at one point. They had managed to invade parts of Europe, India, China, Africa and China simultaneously and took slaves as far north as Iceland - at this point, they had the mightiest army in the world.72

Had someone back then told the Arabs that the primitive Europeans, only 1,000 years later (in 1913) would control approx. 85% of the world’s land mass, almost 80% of its population and 85% of its economy, they would, arguably, have split their sides with laughter. But this is exactly what happened.73 In fact, the West increased its GDP per capita by approximately 300%, between the years 1000 and 1800, whereas, elsewhere in the world GDP rose by only 30%. Already, in 1500, Europe’s GDP per capita had surpassed both India’s and China’s and, in 1600, it was 50 % higher. The Western European nations multiplied their landholdings by a factor of 20 during the Age of Discovery, and the vast majority of this process was conducted within a period of 250 years – within about ten generations.

The fact that the Western European population was very small wasn’t a problem. This can be illustrated by the case of Portugal which, in 1450, was a tiny nation with only 1.2 million people, equivalent to approx. 0.26% of world population.74 And yet, from these humble beginnings, the Portuguese sailed out to build an empire which, for years, was the world’s largest, and which would endure for nearly 600 years. This empire reached at its peak with more than 10 million square kilometres (equivalent more than 100 times Portugal’s own size) and it included settlements in South America, Africa, Middle East, India and the Far East all the way to Japan and down to the islands just north of Australia. Surely a huge project, but the British historian Charles Boxer has estimated that Portugal, at the end of the 16th century, never had more than 10,000 men deployed to control all this.75

One of the theories for this success is that the Renaissance and Enlightenment, combined with individualism, contributed strongly to the enormous achievement of European armies in almost all corners of the world.

The typical Western military commander was not just a superstitious automation, but a fairly creative and rational thinker, and the Western soldier would feel able to bring forwards suggestions to their commanders. The otherwise brutal Spanish conquerer Cortés had studied Latin and worked as a notary, and he was well versed in Greek and Roman literature as well as military history. Many of his men had engineering skills and legal experience, and they were well aware of how different people and civilizations in foreign places could be. Of course, they had no idea what they would meet in South America, but whenever something new turned up, such as armies that outnumbered them massively, they discussed their options freely and ended up using combinations of analysis, engineering and improvisation to find their ways of tackling the problem.

The Indians they confronted were very different and were handicapped by groupism, superstition and insularity. When they encountered the Spanish, they debated whether these were gods or centaurs, whether their ships were floating mountains and whether their guns made thunder. The Aztec emperor Montezuma sent wizards to bewitch the Spanish and, when it came to battle, no one dared to suggest a change of tactics to the emperor.

There are presumably many ways of thinking about this story. One could argue that it was down to a single stroke of luck; for instance, the Western Europeans were just plain lucky that they possessed guns. However, both guns and gunpowder were actually Chinese inventions upon which the Europeans had improved.

Or one could say they were lucky to have invented book printing but the Chinese and Koreans had done the same thing independently - and before the Europeans. Was it their big boats, then? No, the Chinese had been way ahead in ship-building too. Science? Well yes, but the Persians and Arabs had been better at science, at least until around the 12th century.

Here is another narrative: Western Europeans got so far because they were greedy and evil. Sometimes, arguably, they were; but as we shall see later, so were most other people in the world, which was full of slave-traders, rapists, murderers, torturers and warmongers.

No, the key difference was that Western Europeans had become extremely creative in general due to their lucky combination of small units, change agents, networks, shared memory systems, and competition. They had all the conditions in place for developing an amazing creative design space, and other civilizations didn’t.

Here’s a little experiment to illustrate the point. Ask anyone to write down, on a piece of paper, some important inventions that changed the world; say, 10 things. What would they write? Perhaps aeroplanes, cars, trains and the internal combustion engine? Or radio, television and the internet? The exploration of oil and gas, perhaps? Computers, satellites and smartphones? Genetic engineering? Rockets and satellites?

Some might write rock and jazz music. Or birth control pills, anaesthesia and vaccines. Photography perhaps? Or electric power and electric devices such as air-conditioning, electric lights, refrigeration, electric stoves and vacuum cleaners.

All of these things were invented in the West, and the likely outcome of such an experiment is that most, if not all, of the key innovations listed by anyone in the world would be Western. This would be is no coincidence at all, for as we shall see on the following pages, statistical evidence indicates that the West has been responsible for over 95% of all creative innovation; not only in recent decades, but ever.

Yes, ever, and this in despite the aforementioned fact that Western civilization evolved from just 10% of the world’s population inhabiting only 2% of its land surface.

Let’s scrutinise that more closely. We can start with music as a good example of staunch creativity. Here, it was actually Westerners who invented nodes and guitars, pianos, microphones, amplifiers, synthesizers and speakers. It was also Westerners who developed the most popular music genres worldwide, from classical and pop to blues, jazz, rock, beat and virtually all their hundreds of sub-genres. By 2014, the 50 most popular music artists or groups in the world ever were all were Western.76

That’s a big Western dominance, and a survey from 2014 shows, for example, that Western nations throughout history additionally have accounted for:

![]() 96% of the 50 most popular books or book series’

96% of the 50 most popular books or book series’

![]() 100% of the 50 most expensive pieces of art painting or sculture

100% of the 50 most expensive pieces of art painting or sculture

![]() 100% of the 50 highest-grossing film of all time

100% of the 50 highest-grossing film of all time

![]() 100% of the world’s 50 leading luxury brands

100% of the world’s 50 leading luxury brands

![]() 82% of the world’s 50 highest-ranking restaurants

82% of the world’s 50 highest-ranking restaurants

![]() 88% of the world’s 50 top-ranked universities

88% of the world’s 50 top-ranked universities

![]() 100% of the world’s 50 largest biotech companies77

100% of the world’s 50 largest biotech companies77

All these results are global, and when it comes to most expensive or best-selling, it is about all sales ever. These samples indicate a huge Western dominance in art, fashion, luxury and science as well as in biotech, which anyone should recognize as areas that are all largely built on creativity.

The major international auction houses for art, antiques and collector cars are all Western, and the same goes for the largest art fairs. The software companies that have changed people’s daily lives worldwide are predominantly Western, whether that’s Apple, Google, Microsoft, eBay, Amazon, Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube, Skype or Twitter. Some of these have since been copied elsewhere, but the ideas came from the West.

Similarly, the West has pioneered many humanistic movements including the Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and many other organizations. The phenomenon is also reflected in the awarding of Nobel Prizes, where Western nations have taken 92% of all Nobel Prizes and 94% within the exact sciences.78

The immediate impression when you bear in mind all of the above achievements, whether in art, fashion, luxury, science, technology or humanistic endeavours, may be that the West seems to have been responsible for 95% of the world’s total creative output since World War II. But this is not very systematic way to measure it, so are there other ways?

There are, but they show a similar picture. Martin Prosperity Institute is headed by renowned creativity expert Richard Florida and is probably the world’s leading research institute in the factors that create wealth and stimulate creativity. This institution regularly produces a so-called Global Creativity Index and, in 2011, it showed that 17 out of the 20 most creative nations in the world were Western.79 Two other very popular indicators are International Innovation Index from Boston Consulting Group and others80, and Global Innovation Index from Cornell University, INSEAD81 and the World Intellectual Property Organization. Both of these also placed 17 of the world’s 20 most innovative nations in the West. All three studies included Hong Kong and Singapore as two of the top non-Western nations, but both of these are former British colonies with a fairly strong Western influence.

However, all the numbers cited above seem fairly recent, so how does it look if we go further back in time? We have actually a good answer to that, because the reknown social scientist Charles Murray and his associates have performed a massive statistical analysis of who has been responsible for all “human accomplishment”, as they call it, from as early as records could be found and until year 1950, and the result is - as we shall see in a moment – quite astonishing.82 Murray’s objective was to identify all cases in history where 1) a named person had 2) made a creative innovation in art, science or technology that was 3) so important that it was quoted in at least half of the leading modern reference books worldwide.

It was a big project. In fact, it took five years and involved 50 people. The main method was to pore over 163 modern sources of human accomplishment from all over the World and, for each of these, meticulously record the creative people mentioned, as well as how much print space was allocated to each of these. In addition, Murray used a statistical filter as a correction factor where a reference was more often mentioned in reference books from his own country than in other such books.

This work resulted in a list with a total of 4,002 names of generally-respected philosophers, mathematicians, musicians, poets, astronomers, physicists, biologists, technological inventors and so on, who were mentioned in at least half of all the relevant sources. The period covered was approximately 2,750 years (for the reason that, before year 800 BC, no one knows exactly who invented what. For instance, no one knows who invented the stone arrowhead or the bone needle.)

The result showed that the number of new accomplishments had been pretty low and trendless until around year 1000, where they started to pick up, but without accelerating further. It was also scattered around so that, again and again around the globe, there were fairly brief bursts of creativity which then tended to fade or stop abruptly. And although the accumulated human knowledge and abilities overall increased slightly over the first 1,300 years or so, there were long intermittent periods where any upwards momentum in innovation and accomplishment was very difficult to spot.

But then – and here it comes - from approximately 1450, creativity virtually exploded, and that explosion was almost entirely taking place in Western Europe and, subsequently, in the nations that Western Europeans populated.

This does not mean that Europeans had dominated throughout, for as we have already seen, Westerners were actually economic stragglers for a long time. But since the vast majority of all global creativity ever produced happened after 1450, it was Westerners who invented almost any creative invention we can think of. And the consequence of this is that 97% of the total creative thinking from 800 BC to 1950 according to Murrays study was created in the West. And this is indeed astionishing.

So there we have our explanation for why the West came to dominate and we should probably tell children that in school. The West had a unique set of conditions for creativity, and this creativity drove everything else: institutions, work methods, technologies, the arts, everything.

TREND IN HUMAN ACHIEVEMENT (NEW CREATIVITY) FROM 800 BC TO 1950, ACCORDING TO CHARLES MURRAY’S RESEARCH. THE GRAPH DOESN’T SHOW ACCUMULATED CREATIVITY, BUT THE NUMBER OF NEW ACHIEVEMENTS WITHIN EACH PERIOD. UP TO APPROXIMATELY THE YEAR 1000, THERE IS NO CLEAR OVERALL GROWTH TREND, BUT THIS DISGUISES RISING CREATIVE OUTPUT IN WESTERN EUROPA AND DECLINING ELSEWHERE. AFTER APPROXIMATELY 1450, OVERALL CREATIVE OUTPUT EXPLODED, BUT THIS WAS ALMOST ENTIRELY IN THE WEST.83

We have now studied the main early drivers of Western creativity, and these explain how a creative explosion in Western Europe led to its global dominance, and also why this creativity evolved in the first place. However, there still remain some questions:

![]() Which were the most important drivers of the Western European creative explosion; the rivers and harbours, cultural factors, decentralization or what?

Which were the most important drivers of the Western European creative explosion; the rivers and harbours, cultural factors, decentralization or what?

![]() What are the typical reasons that creativity ceases in societies that have previously been very dynamic?

What are the typical reasons that creativity ceases in societies that have previously been very dynamic?

![]() Why did China and the Islamosphere, which were initially ahead, subsequently fall so far behind?

Why did China and the Islamosphere, which were initially ahead, subsequently fall so far behind?

![]() Why did the areas colonized by England become so much more successful than those colonized by Spain and Portugal?

Why did the areas colonized by England become so much more successful than those colonized by Spain and Portugal?

![]() Why was global development in creativity flat and not exponential between 400 BC and 1400 AD?

Why was global development in creativity flat and not exponential between 400 BC and 1400 AD?

We shall address these in the coming chapters.