Over the past year, I’ve had the opportunity to travel throughout Vietnam. From Vung Tau to Sapa, I’ve enjoyed getting to know the people, culture, and cuisine of the country. I found Hanoi to be a vibrant, energetic, and welcoming city that is a world apart from anything I’d previously experienced. As a coleader of Portland State University’s Global Supply Chain Study Abroad program, I traveled to 11 sites, from a purely manual factory to the most state-of-the-art, world-class manufacturing operation I had ever seen.

I’ve worked in many developing countries over the years, and Vietnam reminds me of many of them. The workforce is very solid and trainable, but there are few local junior or middle management personnel. From my observations, the leaders who are there tend to be expats from Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and even Germany. The younger generation (whose parents left a generation ago) are returning, but the skill sets needed to take this pulsating economy to the next level is missing today. Areas such as basic health, safety, and environment (HS&E), planning, supply chain operations, and finance have yet to become core processes, and this can lead to uneven results as businesses attempt to grow.

In my own first taste of manufacturing, I was parachuted into the Toyota plant at Motomachi, Japan. There, I was instructed to “do Kaizen.”1 To my senseis, it didn’t matter that I was the only one who spoke English or that this neophyte American was supposed to teach the masters of continuous improvement how to improve their processes. Rather, I was to observe and walk in their shoes. I discovered and communicated ideas for improving their process. Needless to say, this was a great growth experience and a lesson I was very grateful to learn. It was where I developed the skill of quickly looking at an operation to see how to enhance its pieces without being disruptive to the entire process.

Before we get started, let’s make sure we are on the same page on a few terms and concepts about running a business, including inventory, cycle time, and what the supply chain actually does.

The Business

Management’s principal focus for a business should be on growing profits and cash flow, as these are primary elements in creating shareholder value. Quite often entrepreneurs only focus on their core competencies of designing, marketing, and selling their products. In some cases, they understand manufacturing but fail to grasp the rest of the supply chain as the company grows. Therefore, many companies end up lacking the flexibility and agility to maintain profits through tougher economic times.

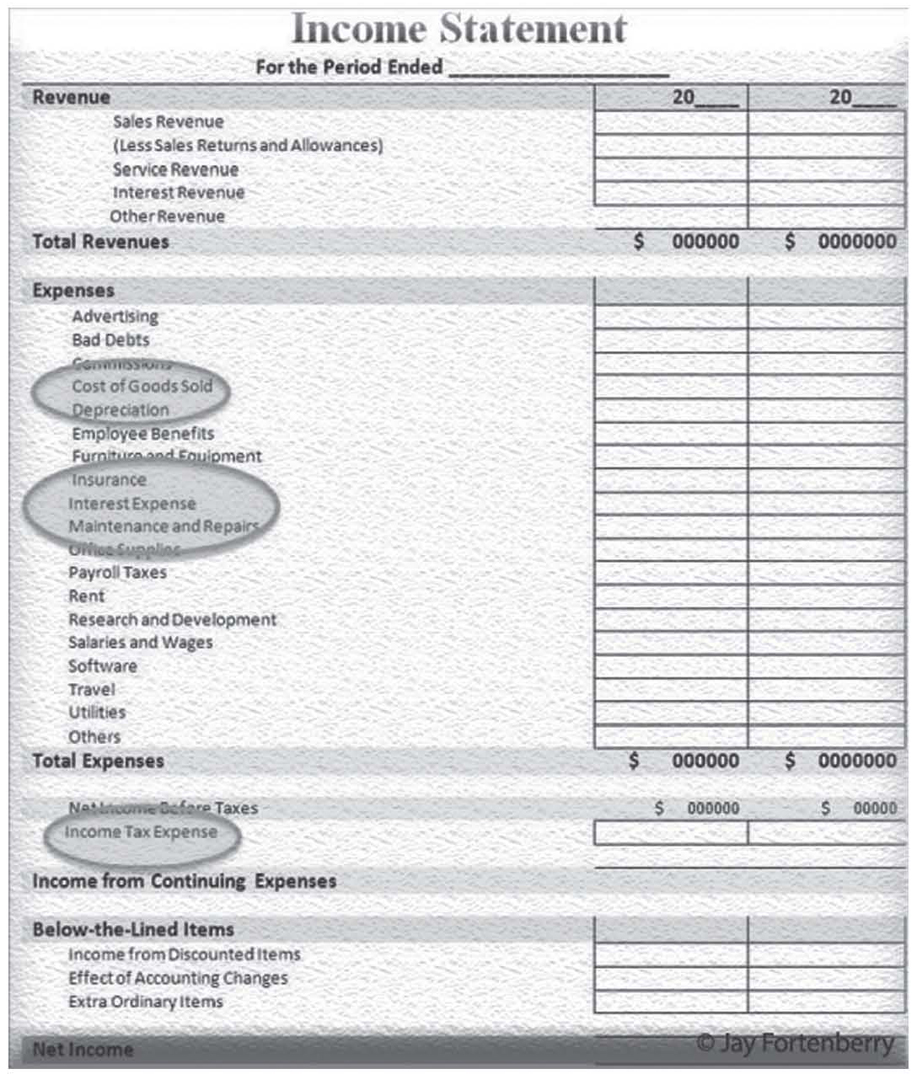

The Balance Sheet

Inventory has its own line on the balance sheet.

And the supply chain can be found throughout the P&L.

Inventory

Inventory is much more than property, goods in stock, and building contents—it’s cash. The purpose of holding inventory is to maximize service and maintain manufacturing efficiency while minimizing the cost of delivering a product. Contrary to popular myth, inventory is located throughout the entire business, not just in a manufacturing or a distribution center.

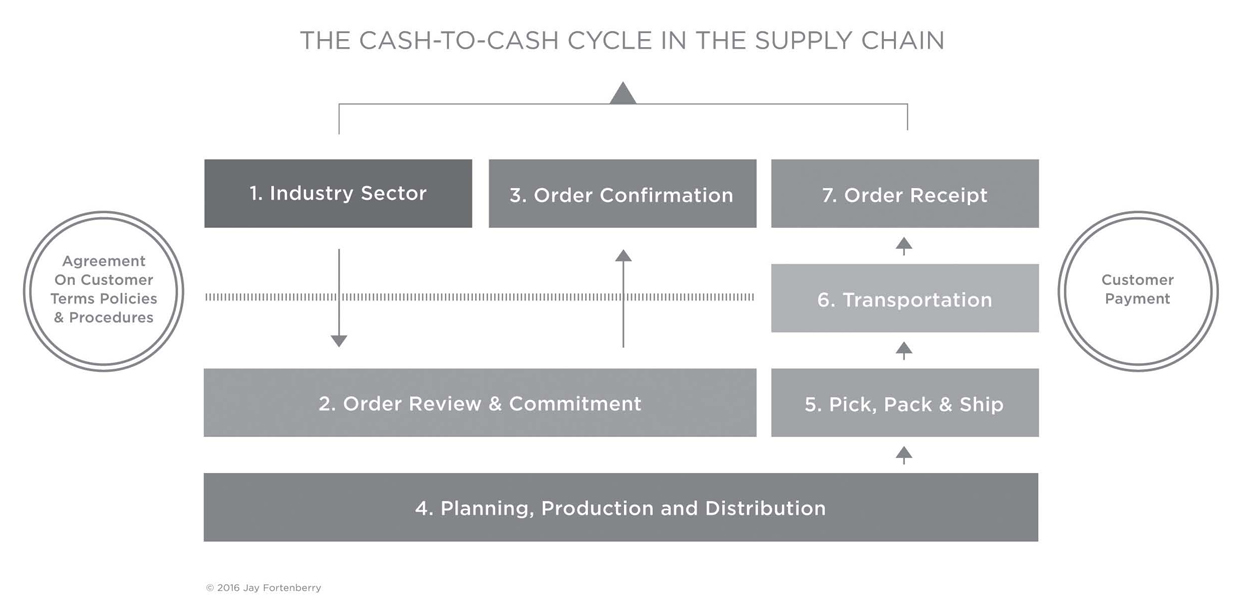

Cycle time is the end-to-end total time from when a customer creates demand until a product is delivered and cash collected. This includes all capital, information, and material flows, as well as any processing and queuing time. By managing cycle time, a business can manage its cash flow. Managing cycle time brings together all of a business’s processes—from customer service to delivery—in order to direct how cash is consumed or the cash-to-cash cycle.*

By managing cycle time improvements, a business can drive performance in a number of key areas:

The first step in managing cycle time is to locate the value stream of a process. Value streams are where value is added to a product or service. Conversely, Muda (or waste)2 takes value away and must be removed from the process. Mapping a process shows how work is completed, how money is spent, and how communications are achieved. Reducing cycle time is not always easy, but understanding the value streams of a business allows you to understand the fundamental ways in which the company is run.

The Supply Chain

The dynamics of a supply chain are continually changing—suppliers are added, investments made in new plants, trade regulations grow, logistics costs increase, and customers change. With the increase in international trade, the supply chain has become increasingly complex and central to the management of cash.

The supply chain is defined as the management of all functions related to the flow of materials from the company’s suppliers to its customers. It includes purchasing, traffic, production control, manufacturing, inventory control, warehousing, and shipping.

The goal of the supply chain is to reduce the overall cycle time for all products and services. This is achieved by the following:

•Understanding and analyzing the products you sell

•Developing a standard approach to cycle time improvement

•Adapting for each specific supply chain of a business

•Pursuing improvements based on effort and impact

•Developing a continuous improvement process that is linked to performance.

Closing Thoughts

Earlier in my career I used to say, “There’s no rule book on how to be a manager.” Forty years and 42 countries ago, I set out to learn this field, which very few knew about at the time. Now I’m writing this book to provide a basic primer for others who choose this path. I hope you find it a valuable reference book on how to become world class, from the wisdom earned at Union Pacific Railroad, John Deere, Toyota, Honeywell, and other great experiences. As I write, teach, and consult these days, I always start with these simple questions:

•Is the supply chain a competitive advantage to the business and how is the strategy defined?

•How is inventory created?

•Is it clear who has ownership of raw, work-in-progress (WIP), and finished goods inventory?

•What metrics drive the business for quality, cost, and delivery?

•Are targets, with time periods, established?

•Has a baseline assessment been done to determine key improvement priorities?

•Have business continuity and disaster preparedness plans been built for the business?

This book answers these questions.

________________

1The asterisk (*) indicates throughout that the term is defined in the Supply Chain Glossary.

2Muda is a Japanese word meaning “futility; uselessness; wastefulness” and is a key concept in lean process thinking, like the Toyota Production System (TPS) as one of the three types of deviation from optimal allocation of resources (the others being mura and muri).