CHAPTER 4

Starting with the Basics

We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.1

—Epictetus, Greek philosopher

So far we have learned about uncertainty and getting to know your audience. Now we’re ready to start with the basics—the foundation for project communications.

There are many books and resources available on the basics of communication. Many of these same basic principles apply to communicating on projects. Some fundamental techniques will be outlined in this chapter, while some are explored further in other chapters. This chapter will focus on the basic tenets of good communication that will help project managers, team members, and project sponsors be effective communicators.

The purpose of this chapter is to help you:

• Look at how high-performing organizations and project teams communicate

• Identify things to consider when communicating on projects, including the need for inclusive language

• Distinguish between formal and informal communications

• Examine the scalability of project communications

• Put it into practice: Project communication basics in traditional, agile, and virtual project teams

Other chapters have additional insights on this topic as well, and Appendix B has more resources and communication books for your reference. We encourage you to also refer to other resources for “general” or “business” communication principles and practices. Our focus here is on project communications.

When it comes to communications, what do high-performing organizations do differently than other organizations? In PMI’s “The High Cost of Low Performance: The Essential Role of Communications” report, their findings show that high-performing organizations:

• communicate key project topic areas better, including the objective of the project, its value for the business, and its outcomes, along with budget, scope, and schedule;

• are better at delivering clear, detailed communications about the project on time, through appropriate channels, with nontechnical language;

• use formal communications plans for nearly twice as many projects as low-performing organizations;

• create project communications management plans that are more than three times as effective as the plans of low-performing organizations.2

As you can see, high-performing organizations communicate effectively and use formal communications plans in their projects. In Chapter 5, we will discuss more about project communications management plans. In this chapter, we will look at some of the basic elements of effective communications in projects.

To get started on thinking about how you can establish a solid foundation for your project communications, let’s begin with a few questions. (By the way, asking questions is an excellent project communications technique to use!)

• As communicators, how can we become more like these high-performing organizations, and become a high-performing project team?

• What does effective communication look like? Does it vary by situations, cultures, experiences, or different types of project teams?

• What elements of project communications are the most challenging?

• How does communicating with individuals within the project team differ from communicating with stakeholders outside the team?

• What do we need to consider when communicating at different levels in the organization?

Keep these questions, and your answers, in mind as you read on. You may have other questions to add as we begin to explore the basics in project communications.

Project Communications Basics: Things to Consider

Things certainly have changed in the way we communicate. Rarely do we use conventional methods of communicating like postal mail, interoffice memo, landline telephone, and facsimile. With project team members located around the world and the desire for instant information, there is a dramatic increase in the use of electronic devices, social media, cloud communication, and technology. Regardless of how you communicate on projects, there is one thing that hasn’t changed—the basics. Let’s begin with a brief overview of some basic principles as well as actions to consider when communicating on projects. Add items from your own experiences as well. Plus, you can refer to Chapter 7 for more on communication tools and to Appendix B for additional resources.

Words Matter

In a leadership role—in projects, business, or other environments— people may hang on to every word you say. Words have an impact. Your words may have a positive impact that encourages and inspires the project team, or your words may have a negative impact where team members “shut down” and resist getting tasks done.

Choose your words carefully, both in writing and orally. You never know what lasting impact, good or bad, your words may have.

Choose your words carefully. You never know what lasting impact your words may have.

Verbal and Nonverbal Communication

As mentioned in Chapter 2, not all communication is verbal or written. There is also tone—the volume or inflection of the words being said. Most important, however, is what is not being said—the body language. This includes facial expressions, eye contact, movement of hands, position of arms and legs, and other factors. Much research has been done (with varying results) on how much of our communication is done through body language. Many scholars conclude that body language makes up a significant percentage of our communication. This makes it especially challenging in working with virtual teams because you are not able to see team members’ body language when you are having a conversation (without using video or a camera device). You must rely mostly on the words being said. Understanding body language and the ability to “read” the nonverbal signals or movements are key skills for communicating on projects.

Listen

Do you listen differently when you are communicating with external stakeholders versus internal project team members? Do you listen more intently when a customer is talking rather than when a colleague is speaking? Listening differently often happens on project teams. Internally, most often the team member does not report to the project manager. Usually, the team member reports directly to a supervisor or functional manager. So why should the team member listen to the project manager, if they don’t report to them? How do you get an executive stakeholder to listen to you when you have little or no authority?

Active listening is an important skill for everyone on the project. The Center for Creative Leadership (CCL), a nonprofit educational institution which focuses on leadership development, has identified six key active listening skills:

1. Be attentive.

2. Keep an open mind.

3. Be attuned to and reflect feelings.

4. Ask open-ended and probing questions.

5. Paraphrase.

6. Share your own thoughts and feelings.3

In your next communication interaction or project team meeting, intentionally put these six active listening skills to use.

Give and Seek Feedback

While listening is important, receiving feedback is equally important. Bill Gates once said, “We all need people who will give us feedback. That’s how we improve.”4 Feedback allows you to make necessary adjustments. For example, you distribute a weekly status report via e-mail on Monday afternoon. Team members are then expected to provide their comments on the status report at the weekly team meeting on Tuesday morning. However, a few members of the project team often do not get a chance to read the report and prepare their comments in that short turnaround time, and as a result the team meetings are not as effective as they could be. By asking for feedback on communication methods, the team members can bring this issue to the attention of the project manager. The project manager can then take action—possibly choosing to adjust the timing of the status report distribution or the team meeting—to allow all team members to contribute more effectively.

Feedback allows you to confirm that the communication methods you are using are working and adjust those methods that are not working. Or, if a method is working for some but not others, remember that you don’t have to get rid of what you have. Rather, you can add a communication method that can support all stakeholders. Feedback on communication processes helps identify potential communication breakdowns before or as soon as they occur. Look for opportunities where you can provide feedback—both as a way to recognize a job well done, and areas where improvement is needed. We will discuss feedback more in Chapter 6.

Deal with “Talkers”

Do you have people on your project team who love to hear themselves talk? These individuals are usually creating and sharing their thoughts at the same time, rather than formulating their thoughts first before speaking. They use “airtime” and seem to never get to the point. One technique to try is the talking spoon; or use any object that you can hold in your hand. A pencil, pen, or marker will also work. The object gives you permission to talk. As long as you are holding the object, it is your turn to speak. When you are done talking, you put the object down on the table, and another person picks up the object. It is now their turn to speak, and it is your turn to listen. This exercise can be done informally without others even knowing it. Or it can be part of your team operating principles (discussed later in this chapter) on giving everyone the equal opportunity to verbally participate. For virtual teams, the object can be something shown on the screen during your video conference calls. At the next opportunity when you experience a team member using too much airtime, give the talking spoon technique a try. As project managers, team members, and stakeholders, we need to be able to articulate our point and let others express theirs.

Avoid Using Technology as a Crutch

Too often, people hide behind the keyboard rather than have conversations. They prefer to send an e-mail or text instead of engaging in a rich, interactive dialogue with another person or group. In having real-time conversations, you might gain valuable information, share new ideas, build relationships, and earn trust. However, meaningful interactions like these take time and effort. The use of technology “encourages us to act as if speed and convenience are the most important criteria for how we communicate.”5 But they are not! Remember that every interaction is important. Step out from behind the keyboard and take advantage of opportunities to have meaningful interactions—either in person or virtually. We will discuss more on the use of synchronous (real-time) and asynchronous communication tools in Chapter 7.

Be Present

With so much happening in today’s dynamic project and working environments, it is easy to be distracted. Our minds are elsewhere. We are constantly interrupted by technology—phone, e-mails, text messages. When we attend project meetings or have project conversations, it is possible that our mind is thinking about other tasks we need to get done. We might even be checking e-mail on our phones while another team member is speaking during a meeting. While we might be physically present, we are not mentally present. The project team needs you (and your mind) at your best on the topic at hand. It needs your active contribution and valuable ideas. Therefore, you need to be “there”—to be present—in every communication, conversation, and interaction.

Define Roles on the Team

For effective project communication, roles and responsibilities on the project need to be clearly defined. This should be done at the project kick-off meeting. To accelerate the process of establishing role definitions, start with roles that have been previously defined in other projects, for example, the project manager, project coordinator, team member, project sponsor, functional manager, etc. At the project kick-off meeting, review the sample roles together. Make adjustments specific to this project and this project team. Make sure that responsibilities for project communication are clearly defined for each role. Once the roles and responsibilities have been established and agreed upon, put the role definitions into your project plan. Everyone should refer to them as needed throughout the project.

Lead by Example

John Wooden, legendary American basketball player and coach, once said, “The most powerful leadership tool you have is your personal example.”6 As a participant on the project team, you should be role modeling what you consider to be good communication practices and acceptable behaviors. If you set good communication examples and actions, psychology indicates that others will follow. It starts with you!7

Avoid Silence

When project team members and stakeholders are not communicating, there is a risk that these groups will start having conversations among themselves. This can create a foundation for even bigger problems, misunderstandings, and potential conflict. A quick “check-in” is better than saying nothing at all. In some company cultures or project teams, silence means acceptance. In other words, if you do not respond, you are agreeing to the decision, action, or content.

Use the Rule of Seven

The origin of the rule of seven started in marketing, where buyers needed to see and hear the same message seven different ways before they would make a purchase. The same concept can be applied to project communication. Aim to repeat the same message seven times, in seven different ways, to ensure everyone understands and receives the same message. What does the rule of seven look like in a project? Here is an example.

Susie is the project manager. She has created a lessons learned document in the electronic project folder. At each status meeting, Susie communicates that no one has posted information in the lessons learned folder and asks everyone to write their lessons learned. At the next team meeting, the lessons learned document (or log) is still empty. To set the example, Susie starts posting information in the lessons learned log and communicates that she has done so. She tries the rule of seven approach, using seven different ways to remind the team to take action. She uses a combination of formal and informal communication, as well as a mix of verbal and written communication. We’ll talk more about formal and informal communication later in this chapter.

1. Susie clearly states the reminder at each status meeting.

2. She includes a lessons learned category in status reports.

3. Susie adds a reminder in her e-mail signature.

4. She posts her own lessons learned each week, then shares the updates with each team member via e-mail.

5. Susie asks each member of the project team to share two lessons learned at the weekly stand-up meeting—one positive result and one negative result.

6. She sets up checkpoints throughout the project to capture lessons learned.

7. Susie creates and shares a short video about lessons learned with the project team.

As a result, she sees that each member of her project team is now actively participating in capturing lessons learned on the project. The rule of seven really does work! Consider doing a similar activity: Try delivering the same message in seven different ways and see the difference. Then share the results with your project team.

Use Push, Pull, and Interactive Methods

On a project, there are numerous communication methods that the project team will use. Push communication methods require that the information be sent out. Pull communication methods require individuals to come to where the information is located, whether that location is physical or virtual. Interactive communication methods use an exchange of information. In their book Contemporary Project Management, Timothy Kloppenborg, Vittal Anantatmula, and Kathryn Wells provide examples of each method (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Examples of push, pull, and interactive communication methods8

Push methods |

Pull methods |

Interactive methods |

|---|---|---|

Instant messaging Voicemail Text Project reports Presentations |

Shared document repositories Intranet Blog (repository) Bulletin boards Kanban boards |

Phone call Teleconference Wikis VOIP/videoconferencing Groupware Meetings |

Utilize Training

Project management is both about knowledge (training) and experience. To qualify for many project management certifications, both project education hours and project experience hours may be required. Most project professionals have taken classes and studied project management. However, how much training have we done to learn about communicating? If 90 percent of a project manager’s time is spent communicating, can we be really good at it just by experience? Probably not. Consider taking some communication classes. Read books on project communication— including this one! Follow blogs to learn more about effective communication. If you do not know where to begin, refer to Appendix B for a list of books and other resources.

Be a Continuous Learner

Look for opportunities to grow your communication skills, knowledge, and experience. Dr. Donald Clifton, psychologist, educator, and developer of the CliftonStrengths® assessment, said, “To produce excellence, you must study excellence.”9 Start doing both today—studying and producing project communication excellence.

Implement Team Operating Principles

Team operating principles (or ground rules) outline the way communication is handled, what to expect, and who is responsible, along with many other aspects of working together. Some people call it a “team contract” or “team agreement.” Regardless of what it is called, it shows formally that all team members have made a commitment on how they will work together—including communication protocols and expectations.

Too often on a project team, we hear, “What are you expecting from me?” During the project kick-off meeting, make sure that expectations are set, aligned, and agreed upon as individuals and as a team. Establishing expectations can be a mechanism to reduce uncertainty for team members and reduce risk in the project by providing clarity for stakeholders. Setting clear expectations is essential and should be documented in the team operating principles and role definitions.

A list of sample ground rules can be found in Appendix E. Exhibit 4.1 highlights some ground rules specifically for communication protocols and setting expectations.

Sample ground rules for team communications

• The project manager will send a status update every Friday via e-mail by 5:00 p.m.

• Team leaders are responsible for updating any tasks that are impacted by the status update no later than 9:00 a.m. on Monday morning.

• Team members should talk with a team lead for clarification about tasks.

• The project sponsor is responsible for updating the leadership team on the project’s status at least once a month or as requested.

• Inquiries about the status of the project that come in to any member of the team should be reported to the project manager.

• The project team will have at least one monthly face-to-face meeting or teleconference for an internal status update. All team members are expected to attend and participate in the meeting.

• All meeting invitations must include an agenda or description of the purpose of the meeting and the expected outcomes.

• No cell phones are to be used in project meetings; laptops should only be used for notetaking or other actions relevant to the meeting (no checking e-mail).

• If you are making a task or assignment, provide a clear, specific deadline of when you need it.

• Keep e-mail threads on topic. If you need to discuss a new topic, send a new e-mail rather than a reply.

To be most effective, ground rules should be established together as a team. This ensures everyone participates in creating the ground rules and has an opportunity to ask questions for increased clarity; it also creates greater buy-in so that the ground rules are more likely to be used and followed. Ground rules should be revisited regularly (more frequently in the beginning of the project) to ensure that communications are being executed effectively both inside and outside the project team. Another benefit of setting initial guidelines around communication is that they can divert the target of individuals’ displeasure from other people to the process, which can depersonalize communication breakdowns and avoid conflict. We will talk more about conflict in Chapter 9.

Your team’s operating principles will probably look different from Exhibit 4.1. The key is (1) to have them, (2) to create them as a group, and (3) to use them.

Team ground rules:

1. Have them.

2. Create them as a group.

3. Use them.

Use Inclusive Language—No Jargon

Many professions have their own terminology and word usage to talk about what they do and how they do it. You may have experienced this when talking with someone from another area of expertise, and had difficulty understanding the technical language they used to describe a function of their work. Project management has its own language as well, and you should be cautious about using that language with stakeholders—both inside and outside the project team—who are not project managers or experienced project professionals. Use words and expressions that are inclusive of all individuals and groups. Jargon and technical language can exclude others, which can create uncertainty, misunderstanding, and conflict.

As noted in Chapter 1, the call to communicate “in the project language” was removed in the very first revision of the PMBOK® Guide. In PMI’s “The High Cost of Low Performance: The Essential Role of Communications” report, one of the biggest problem areas in project communication stems from “challenges surrounding the language used to deliver project-related information, which is often unclear and peppered with project management jargon.”10 When projects are communicated “in the language of the audience,”11 the project is more likely to succeed. Knowing your audience (see Chapter 3) helps you know the language to use when communicating about the project. In general, however, a good rule is to limit project management jargon to only those on the project team whom you are certain will understand the language.

You may want to adjust the language you use when communicating with different levels in the organization as well, based upon their interests. For example:

• When communicating with executives and senior management, their interest may be the bottom-line impact and a high-level summary of the project.

• When communicating with functional managers, their interest may be in the people and resources, specifically the team members they have assigned to work on the project.

• When communicating with outside stakeholders, their interest may be in progress, status updates, and results achieved.

• When communicating with the project team, their interest may be staying on schedule, completing tasks, addressing risks, and delivering project success.

Whatever their interest, know your audience and adjust your communication to be inclusive of who they are and what their stakes are in the project (see Chapter 3).

Formal and Informal Communication

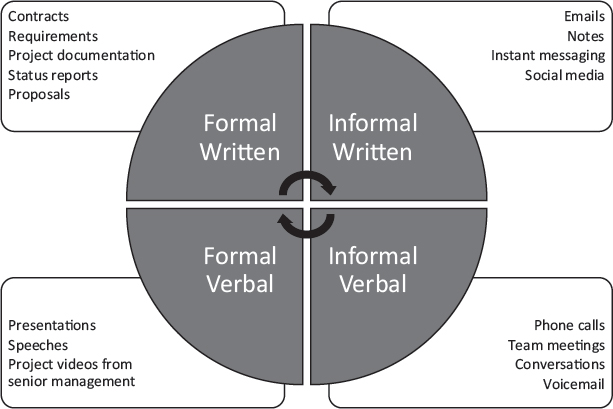

As we work and communicate with different levels in the organization, we also use different communication methods. You can categorize most project communications into four types: formal written, informal written, formal verbal, and informal verbal12 (Figure 4.1). What are examples of each type?

• Formal written—When you are documenting a project problem, signing a vendor contract, or preparing documentation for your project (project charter, status reports, etc.), this is formal written communication. Typically, formal written communication requires planning or preparing.

Figure 4.1 Types of formal and informal communication

• Informal written—When you send an e-mail or text message, or hand a note to someone about the project, this is a type of informal written communication.

• Formal verbal—When you give a speech or deliver a presentation with project updates, this is formal verbal communication. Again, there is an element of planning or preparation.

• Informal verbal—When you are chatting with your colleagues about the project, or meeting for coffee to discuss project tasks, this is a type of informal verbal communication.

Choose the right type of communication based on the outcome(s) you are trying to achieve. Be cautious when using informal communication where action or documentation is needed. For example, you have a spontaneous conversation with another project team member and say, “Oh, can you please take care of that?” Then nothing happens. There is no follow-up because it is not documented. In project management, if it is not documented, it didn’t happen!

In project management, if it is not documented, it didn’t happen!

Scaling Communications for Project Size

When communicating, the size and complexity of the project will impact your communication. A small project may have more informal communication than a large project. A colocated project team where everyone sits together may have more flexibility in communicating, since it is easier to walk over and talk with another team member face-to-face. On regulatory projects, you may have more formal communication—written and verbal—than on nonregulatory projects. Regardless of the project size or type, we need to scale our communications to fit.

What does “communication scaling” mean? Like many aspects of project management, it depends on the project. Here are some considerations as you scale your communications for the project at hand.

Communication scaling can pertain to the amount of communication or information shared. Depending on the complexity and priority of the project, you may only need to communicate status updates on a weekly basis, or you may need to provide in-depth progress reports to some individuals or groups on a near-daily basis. Senior executives tend to like “at-a-glance” communication methods like dashboards. A dashboard provides only high-level information, similar to an executive summary. Then the executive can ask for more details if desired. (As project managers, we need to be ready to communicate the details at all times!) Effective project managers scale their communication to create the “dashboard” effect—with communications that provide high-level overviews of what is happening on the project, as well as detailed background information ready when stakeholders need it. (We will talk more about dashboards as a communication tool in Chapter 7.)

Communication scaling can pertain to the impact of miscommunication. When we have one-on-one or interpersonal communication, there is no scaling. Any miscommunicated information initially stays between the two parties and can be clarified more easily, especially when corrected as soon as possible. However, if we send the wrong message to a large group of stakeholders, your poor communication can scale exponentially. You can cause difficulties with a larger group of stakeholders; this makes the problem harder to correct, and also opens the door to further damage as those stakeholders discuss it with even more people and further amplify the damage caused by the poor communication.

Communication scaling can pertain to the different types of groups. Different organizations involved in the project will require communications specific to their role. Public stakeholder groups who do not participate in but are affected by a project (for example, community members impacted by a construction project) will need separate communications that address their interests in the project. See Chapter 3 for more about understanding your audience.

Communication scaling can pertain to the number of people involved. Small projects may require relatively few communication methods, especially if there are only a few team members or external stakeholders. Large projects will require you to scale your communications using many different methods for many different audiences, such as multiple organizations participating in the project and multiple stakeholder groups.

Communication scaling can pertain to tools. You can build efficiencies into your project communications by utilizing the tools which best serve your different audiences. The project team, for example, might function most efficiently when using a cloud-based team collaboration tool. An Internet site might work best when there is a large project with many stakeholders, offering extensive information that multiple groups need to access. (See Chapter 7 for more about choosing communication tools.)

Communication scaling can pertain to the diversity of the audience. You may need to add more methods of communication or more frequent communication to your plan to accommodate the information needs of diverse stakeholders. It is essential to get regular feedback to make sure that your message is delivered and clearly understood. (See Chapter 6 for more information on feedback.)

Putting It into Practice

Here are a few practical tips, fun activities, and useful ideas for how you can implement the concepts in this chapter into your project environment. Note that ideas listed in one type of team may be adapted to other teams. Be creative. Use these as a starting point. Add your own ideas to build your communications toolkit.

Traditional project teams |

• Set the example: Demonstrate good project communication behaviors you expect from other team members. • Put a “jargon jar” in your team room. Every time a team member uses project management jargon with an outside stakeholder, they must contribute a small amount of money to the jar. At the end of the project or at a project milestone, use the money in the jar to buy the team a treat, such as coffee, lunch, or gift cards (depending on how much money is in the jar). • Try the talking spoon exercise in your team meetings. Only the person holding the spoon (or any other object you can hold, such as a marker) can speak. When that person is finished, they put down the spoon and then another person can pick it up and speak. |

|

Agile project teams |

• As a team, create ground rules for your stand-up meetings so that everyone is on board with the process. • Make sure each meeting has a facilitator to keep the conversation on track. Ask a different team member to serve as facilitator for each meeting so they can gain valuable experience. • For those who have an interest in your project, invite them to attend sprint reviews. This will show the team “in action” and validate the work that has been completed. Over time, it will strengthen trust and relationships, and reduce stakeholder uncertainty. |

|

Virtual project teams |

• Have each member of the team share what they think it means to be a “high-performing project team.” • Choose a unique term that you might use in your project, such as “virtual roundtable.” Have each member of the team share how they interpret that term. • Look for opportunities to use both formal and informal communication. |

|

Summary

Whether you are communicating on a project, or communicating in general, it is important to start with the basics. Use practical techniques and sensible approaches for effectively delivering your message. Research has shown that high-performing teams and organizations are better at communicating key project concepts, delivering their messages in a timely manner using inclusive language and the right methods, and effectively using formal project communications management plans. With the increase in the number of different ways to communicate, there are many things to consider in your project communications.

Scaling your project communications pertains to the amount of communication shared, the impact of the communication, the size and types of stakeholder groups, the various tools, and the diversity of the audience. And don’t forget that words matter. Regardless of how they are delivered—formal, informal, written, or verbal—words have a lasting impact!

Key Questions

1. Review the “Things to Consider” section at the beginning of this chapter. What would you add from your own experiences when communicating on projects?

2. In your next communication interaction or project team meeting, intentionally put the six active listening skills listed in this chapter to use.

3. Try delivering the same message in seven different ways and see the difference. Then share the results with your project team.

Notes

1. Toastmasters International (2019), accessed September 23, 2019, https://www.toastmasters.org/magazine/magazine-issues/2019/sep/inspiring-quotes-for-leaders.

2. Project Management Institute (2013), p. 6.

3. Center for Creative Leadership, https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectively-articles/coaching-others-use-active-listening-skills/.

4. Bill Gates, https://www.azquotes.com/author/5382-Bill_Gates/tag/feedback.

5. Tumlin (2013), p. 22.

6. Wooden, https://www.azquotes.com/quote/866260.

7. Tumlin (2013), p. 34.

8. Kloppenborg, et al. (2019), p. 190.

9. Clifton and Anderson (2006), p. xv.

10. Project Management Institute (2013), p. 4.

11. Project Management Institute (2013), p. 5.

12. Burke and Barron (2014), p. 292.

References

Bill Gates. 2019. https://www.azquotes.com/author/5382-Bill_Gates/tag/feedback, (accessed May 30, 2019).

Burke, R. and S. Barron. 2014. Project Management Leadership: Building Creative Teams. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Center for Creative Leadership. 2019. “Use Active Listening to Coach Others.” https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectively-articles/coaching-others-use-active-listening-skills/, (accessed August 5, 2019).

Center for Creative Leadership and M. H. Hoppe. 2006. Active Listening: Improve Your Ability to Listen and Lead. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Clifton, D. O., E. Anderson, and L. A. Schreiner. 2006. StrengthsQuest: Discover and Develop Your Strengths in Academic, Career, and Beyond. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

Kloppenborg, T. J., V. Anantatmula, and K. N. Wells. 2019. Contemporary Project Management, 4th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Project Management Institute. 2013. “The High Cost of Low Performance: The Essential Role of Communications.” Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Toastmasters International. September, 2019. “Inspiring Quotes for Leaders.” https://www.toastmasters.org/magazine/magazine-issues/2019/sep/inspiring-quotes-for-leaders, (accessed September 23, 2019).

Tumlin, G. 2013. Stop Talking, Start Communicating. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Wooden, J. 2019. https://www.azquotes.com/quote/866260, (accessed August 8, 2019).