Chapter Two

Concepts and Theories of Business Ethics

INTRODUCTION

We have already seen in the introductory chapter that the word ethics is derived from the Greek word ethikos meaning character or custom. Today we use the word ethos in a different connotation meaning a characteristic, or attitude of a group of people, culture and so on. When we talk of ‘business ethos’, we mean the attitude, culture and the manner of doing business of the business community. Philosophers generally distinguish ‘ethics’ from ‘morality’. To them while ‘morality’ refers to human conduct and values, ‘ethics’ refers to the study of human character or behaviour in relation to moral values, that is, the study of what is morally right or morally wrong. In ordinary parlance, however, people use these expressions interchangeably. When we say something was done ‘ethically’ or ‘morally’, we mean that things were done correctly.

DEFINITIONS OF ETHICS

Ethics is a branch of axiology which together with metaphysics, logic and epistemology constitutes philosophy. Ethics attempts to find out the nature of morality, and to define and distinguish what is right from what is wrong. Ethics is also called moral philosophy. Ethics according to Manuel G. Velasquez “is a study of moral standards whose explicit purpose is to determine as far as possible whether a given moral standard (or moral judgement based on that standard) is more or less correct”.1 Many ethicists assert that there is always a right thing to do based on moral principle, while others subscribe to the broader view that the right thing to do depends on the situation. To many philosophers, ethics is just a ‘science of conduct’. Epicurus, the philosopher, defined ethics as a science that “Deals with things to be sought and things to be avoided with ways of life and with telos,” which means the chief aim or end in life.2

Like one of its later-day offshoots, economics, ethics is also imprecise, as it deals with human behaviour that cannot be placed into a straitjacket. It is said that when there are five economists, there will be six different opinions. Likewise, philosophers have been discussing ethics at least for more than 2500 years—since the time of Socrates and Plato, but they have not been able to arrive at an acceptable definition. Moreover, the area of study encompassing ethics is vast and covers the length and breadth of human behaviour, and that makes it far more difficult to comprehend.

Many ethicists prefer to call ethics as the study and philosophy of human conduct, with an emphasis on determining right and wrong. While most dictionaries define ethics as the science of ‘morals in human conduct’, ‘moral philosophy’, ‘moral principles’, ‘rules of conduct’, etc., the definition of The American Heritage Dictionary is more focused: “The study of the general nature of morals and of specific moral choices; moral philosophy; and the rules or standards governing the conduct of the members of a profession”.3 According to Ferrel et al.4 “Values and judgements play a critical role when we make ethical decisions” as compared to ordinary decisions.

In sum, ethics as a moral and normative science refers to principles that define human behaviour as right, good and proper. However, it should be stressed that these principles do not lead to a single course of action, but offer a means of evaluating and deciding among competing options.

PERSONAL ETHICS AND BUSINESS ETHICS

Personal ethics refer to the set of moral values that form the character and conduct of a person. Organization ethics, on the other hand, describes what constitutes right and wrong or good and bad, in human conduct in the context of an organization. It is concerned with the issue of morality that arises in any situation where employers and employees come together for the specific purpose of producing commodities or rendering services for the purpose of making a profit. An organization can be described as a group of people who work together with a view to achieving a common objective, which may be to offer a product or service for a profit. Organization ethics, therefore, deals with moral issues and dilemmas organizations face both in business and non-business settings that include academic, social and legal entities.

MORALITY AND LAW

Philosopher James Rachels suggests two criteria fulfilling a minimum conception of morality—reason and impartiality. By the use of reason, Rachels means that a moral decision must be based on reasons acceptable to other rational persons. The criterion of impartiality is fulfilled when the interests of all those affected by a moral decision are taken into account, with of course, the recognition of finite knowledge of the repercussions of any ethical decision. Following Rachels, then, any legitimate moral theory must meet the tests of reason and impartiality. People often tend to confuse legal and moral issues. These are two different things. Breaking an unjust law is not necessarily immoral. Gandhiji during his Dandi Yatra broke the law the British made in India to the effect that one who produced salt would have to pay a tax. His civil disobedience movement also was meant to disobey or even to break the British-made law. By no stretch of imagination, these acts of the Father of the Nation could be considered immoral. Likewise, the legality of an action could not automatically be considered morally right. William Shaw in his book Business Ethics brings to focus two contexts to illustrate this situation5:

- An action can be illegal, but morally right. For instance, during the freedom struggle many wanted freedom fighters (criminals according to the colonial rulers) had hidden themselves in the houses of patriotic Indians to save themselves from prosecution and imprisonment. Though this was against the British law in India, this patriotic deed of freedom-loving Indians was no doubt an admirably brave and moral action.

- An action that is legal can be morally wrong. For instance, a profit-earning company anxious to retain its top brass may sack hundreds of its workers to save enough money to pay the former with a view to getting their guidance and managerial expertise. This act may be perfectly legal but morally unjustified.

Then, how do we understand the relationship between law and morality? Generally, law codifies a nation’s ideals, norms, customs and moral values. However, changes in law can take place to reflect the conditions of the time in which they are enunciated. For instance, during the British rule in India, several laws were enacted that benefited the colonial power and its maintenance, and militated against the interests of natives. To keep those laws even after independence would not only be unanachronistic but also totally out of place. Moreover, even if a nation’s laws are both sensible and morally sound, they may be insufficient to establish moral standards to guide the people. The law cannot cover the wide variety of possible individual and group behaviour and in many situations is an inadequate tool to provide moral guidance.6

There is thus a clear-cut difference between law and morality. In a particular situation, an act can be legal but will not be morally right. For example, it will be legal for an organization which is running in loss to lay off a few employees so as to exist in the business situation. But it is not morally right to do so, because the employees will find it difficult to find a living. On the other hand, an action performed can be illegal but morally right. For example, it was illegal to help the Jewish family to hide from the Nazis, but it was a morally admirable act.

In the organization too, we will find such situations where an act will be morally right and legally wrong to perform. The strong ethical base of the individual as well as of the organization would come to the rescue of that situation. The law cannot cover the wide variety of possible individual and group conduct. Instead, it prohibits actions that are against the moral standards of the society.

HOW ARE MORAL STANDARDS FORMED?

There are some moral standards that many of us share in our conduct in society. These moral standards are influenced by a variety of factors such as the moral principles we accept as part of our upbringing, values passed on to us through heritage and legacy, the religious values that we have imbibed from childhood, the values that were showcased during the period of our education, the behaviour pattern of those who are around us, the explicit and implicit standards of our culture, our life experiences and more importantly, our critical reflections on these experiences. Moral standards concern behaviour which is very closely linked to human well-being. These standards also take priority over non-moral standards, including one’s self-interest. The soundness or otherwise of these, of course, depends on the adequacy of the reasons that support or justify them.

RELIGION AND MORALITY

Many people believe that morality emanates from religion, which provides its followers its own set of moral instructions, beliefs, values, traditions and commitments. If we take Christianity as an illustration, it offers its believers a view that they are unique creatures of Divine Intervention “that has endowed them with consciousness and ability to love”. They are finite and bound to earth, and having been born morally flawed with the original sin, they are prone to wrongdoing. But by atoning for their sins, they can transcend nature, and after death, become immortal.7 One’s purpose in being born in this sinful world is to serve and love one’s Creator. For the Christian, the way to do this is to emulate the life and example of Jesus Christ who was the very embodiment of love and sacrifice. What greater love and sacrifice there can be than to lay down one’s own life for the sake of those whom you love? Christians find an expression of love in the life of Christ who died on the Cross to atone for the sins of mankind whom He loved abundantly. Their expression of this love is shown when they perform selfless acts to help even strangers in distress, develop a keen social conscience, and is therefore made intrinsically worthwhile. Service to fellow human beings is an inalienable part of the Christian virtue. Has not Jesus enjoined His followers: “Whatever you do to the least of my brethren, that you do unto Me”? The life of Mother Teresa epitomized this basic Christian virtue of love that found expression in her selfless service to the lepers, the hungry and those afflicted with serious and terminal diseases. This commitment of love towards one’s fellow human beings hones the Christian sense of responsibility not only to his family but also to the wider community.

Unlike in Christianity where most of the moral principles are drawn from the teachings of Christ who also provided the interpretations for the Ten Commandments and other moral standards gleaned from the Old Testament, Hinduism, the major religion in India, does not provide one acceptable source of moral standards. The Hindu view of moral standards is drawn from a large and bottomless cauldron that contains values accrued from various religious beliefs. The Hindu moral standards are examplified in works such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagavad Gita, Panchatantra, Naganantham and the Jataka tales. One of the common fundamental areas of agreement which can be called the Indian religious tradition is the theory of Karma, the doctrine of the soul and the doctrine of mukti (freedom).8 Almost all the Hindu religious traditions agree in the belief that a person’s actions leave behind some sort of potency which provide the commensurate power to ordain joy or sorrow in the person’s future birth. When the fruits of action are such that they cannot be enjoyed in the present life, it is believed that the benefits for righteous deeds or penalties for wrong doing will be reaped in the person’s next birth, as a human or any other being. It is also believed that the unseen potency of the action generally requires some time before it could give the doer the merited enjoyment of benefit or punishment. These would accrue and set the basis for enjoyment and suffering for the doer in the person’s next life. Only the extreme fruits of those good or bad actions can be reaped in the person’s present life.9 The nature of a person’s next birth is determined by the pleasant or painful experiences that have been made ready for that person by the maturing actions in this life. The Bhagawad Gita also underlines the fact that a person has a choice in action, but never in its outcome. The results are determined the moment the action is carried out—the fruits thereof cannot be avoided, and in any case, are not under the control of human beings. Therefore, people should concentrate on their actions without worrying about the results they will bring.

All Hindu religious thinking leads to the general principles of ethical conduct that must be followed for the attainment of salvation. Controlling all passions, no injury to life in any form, and a check on all desires for pleasures, are principles which are acknowledged universally in all Hindu traditions and beliefs. The Indian religious philosophy drawn from the Hindu ethos and tenets provide a rich tapestry for ethical theories. The Hindu sage Thiruvalluvar, through his magnum opus, Thirukkural, has provided ethical prescriptions for the overall well-being of people.

Religion, therefore, provides not only a formal system of worship, but also a prescription for social intercourse. William H. Shaw quotes the most celebrated religious mandate which is found in almost all major religions of the world “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”. Termed the ‘Golden Rule’, this injunction epitomizes one of mankind’s highest moral ideals. But then, though religious ideals, teachings and thoughts provide a platform for enunciation of what constitutes moral behaviour and are always inspiring, these are very general and can hardly provide guidelines for precise policy injunctions. Nonetheless, religious organizations do take positions and articulate their stands on specific issues on such diverse fields of human endeavour as politics, education, economy, administration and medicine. They also help mould public opinion on such important national social issues as abortion, euthanasia, homosexual relations, and international issues as nuclear weapons and developmental assistance to poor countries to fight poverty, HIV etc. The Roman Catholic Church has a rich tradition of trying to translate its core values to the moral aspects of industrial relations. Several Popes in the 20th century had spread the Catholic religious ideals through their encyclicals and pastoral letters such as Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum (1891) and Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Contesimus Annus (1991). Likewise, the Catholic Bishops’ Conferences in many major countries issue pastoral letters to their flock and take stands on important socioeconomic and even political issues.

MORALITY, ETIQUETTE AND PROFESSIONAL CODES

It is also necessary to understand the differences between morality and etiquette, and morality and law. While morality is the moral code of an individual or of a society, etiquette is a set of rules for well-mannered behaviour. Etiquette is an unwritten code or rules of social or professional behaviour such as medical etiquette. Morality can be also differentiated from law which consists of statutes, regulations, common law and constitutional law. Morality is different from professional codes of ethics which are special rules governing the members of a profession, say of doctors, lawyers and so on. Morality is not necessarily based on religion as many people think. Although we draw our moral beliefs from many sources, for ethicists the issue is whether these beliefs can be justified.

When people work in organizations, several aspects of corporate structures and functions tend to undermine a person’s moral responsibility. Organizational norms, group commitment to certain goals, pressure to conform and the diffusion of responsibility can all make the exercise of personal integrity in the context of an organization difficult. Moral principles provide confirmatory standard for moral judgements. This process, however, is not mechanical. Principles provide a conceptual framework that guides people in making moral decisions. Careful thoughts and reflection with an open mind are very necessary to work from one’s moral principle to make a moral judgement. A person can hold a moral or ethical belief only after going through a process of “a conscientious effort to be conceptually clear, to acquire all relevant information, and to think rationally, impartially and dispassionately about the belief and its implications.”10

MANAGEMENT AND ETHICS

Management of any business involves hundreds of decisions. Ethical issues occur in all decision making processes. Conflicts and ethical dilemmas are part and parcel of such processes. There arises a continuous conflict between the goals of an organization and various issues relating to its day-to-day management. The success of any business organization is measured by revenues, profits, cost-cutting, quality, quantity, efficiency, and so on. These objectives of the organization may run in direct conflict with its social commitment which is measured in terms of obligations to stakeholders, both within and outside the organization. For instance, cost-cutting may be used as a tool to enhance revenue and profit. In the process of realizing this objective, the company may have to lay off some workers. This creates a conflict between the organizational goal and the business units’ obligation to the stakeholders, in this case, the discharged workers. These issues, of course, will differ from organization to organization, people to people and the problems and issues thrown up in each case may lend themselves to different interpretations. For its own survival, it is necessary that the organization should maintain its competitive edge in the market. It should produce useful, safe, and quality products and services at affordable prices. While doing so, the organization should ensure that the interests of the stakeholders are not adversely impacted. This requires a fine balancing act on the part of the organization.

The dilemmas and conflicts that managements encounter during decision making processes and their obligations to stakeholders require a balancing act, involve analytical approach, and sound decision making in view of the fact that each of such decisions has its own rewards and penalties. Some of these decisions may have an impact on the health and safety of consumers. Sometimes, in order to push the sales of products, managers may be prompted to resort to deception, or suppressio veri, suggestio falsi. This creates a conflict of interest for them between their obligation to their organization and their obligation to consumers and other stakeholders. The business managers need to recognize the impact of their decisions and actions on their own organization and the community at large. A clear understanding of the moral consequences of their decisions and the manner of implementing them on all stakeholders is required at all levels in the organization. This may not be as simple as it sounds, because not all ethical questions have simple ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answers. “In practice, the ethical questions have many alternatives with different probabilities of occurrence and have different impacts on stakeholders. Each set of choices will have different economic and social consequences and may lead to further decision points.”11

NORMATIVE THEORIES

Ethics is a normative study, that is, an investigation that attempts to reach normative conclusions. It aims to arrive at conclusions about what things are good or bad, or what actions are right or wrong. In other words, a normative theory aims to discover what should be, and would include sentences like ‘companies should follow corporate governance standards’ or ‘managers ought to act in a manner to avoid conflicts of interests’. This is the study of moral standards which are correct or supported by the best reasons, and so “attempts to reach conclusions about moral rights and wrong, and moral good and evil”.12 For instance, the stakeholder theory has a ‘normative’ thrust and is closely linked to the way that corporations should be governed and the way that managers should act.

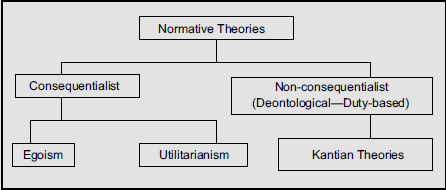

There are different normative perspectives and ethical principles that often contradict one another. There are consequentialist and non-consequentialist normative theories (Fig. 2.1). In the organizational context, we can identify the following ethical theories that have an impact on the manner in which ethics or the lack of it could be identified in a business organization. These are, according to William H Shaw,13 the following:

- Egoism, both as an ethical theory and as a psychological theory

- Utilitarianism, the theory that a morally right action results in the greatest good to the largest number of people.

- Kant’s ethics, with his emphasis on moral motivation and respect for persons.

- Other non-consequentialist normative themes: duties, moral rights, and prima facie principles.

ETHICAL THEORIES IN RELATION TO BUSINESS

Egoism

“The view that associates morality with self-interest is referred to as egoism.”14 Therefore, it can be said that egoism is an ethical theory that treats self-interest as the foundation of morality. Egoism contends that an act is morally right if and only if it best promotes an agent’s (persons, groups or organizations) long-term interests. Egoists make use of their self interest as the measuring rod of their actions. Normally, the tendency is to equate egoism with individual personal interest, but it is equally identified with the interest of the organization or of the society.

Fig. 2.1 Classification of Normative Theories

Decisions based on egoism mainly are intended to provide positive consequences to a given party’s interest without considering the consequence to the other parties. Philosophers distinguish between two kinds of egoism: personal and impersonal. The personalist theory argues that persons should pursue their longterm interest, and do not dictate what others should do. Impersonal egoists argue that everyone should follow their best long-term interest. It does not mean that an egoist will act against the interest of the society. They may be able to safeguard their interest without hurting the interest of others. When an organization performs or safeguards its interest without hurting the interest of others, then we can say that the organization acts ethically.

Psychological Egoism

Egoism asserts that the only moral obligation we have is to ourselves, though it does not openly suggest that we should not render any help to others. However, we should act in the interests of others, if that is the only way to promote our own self-interest.

Ethicists who propose the theory of egoism have tried “to derive their basic moral principle from the alleged fact that humans are by nature selfish creatures.”15 According to these proponents of psychological egoism, human beings are so made that they must behave selfishly. They assert that all actions of men are motivated by self-interest and there is nothing like unselfish actions. To them, even the so-construed self-sacrificial act like, say, whistle-blowing in an organization to bring to the notice of the top brass the unethical acts practised down the line, or by top executives, is an attempt by the whistle-blower to either take revenge or become a celebrity.

Criticism of the Theory of Psychological Egoism Though there are a few advocates of the theory of egoism even today, one would hardly come across philosophers who would propose it as the basis for personal or organizational morality. Generally, the theory is criticized on the following grounds:

- Egoism as an ethical theory is not really a moral theory at all. Those who espouse egoism have very subjective moral standard, for they want to be motivated by their own best interests, irrespective of the nature of issues or circumstances. They never try to be objective, and everything is viewed subjectively based on whether it would promote their own self-interests or not.

- Psychological egoism is not a sound theory inasmuch as it assumes that all actions of men are motivated by self interest. It ignores and undermines the human tendency to rise above personal safety as proved in thousands of examples of personal sacrifices at times of calamities such as floods, earthquakes and other natural disasters.

- Ethical egoism ignores blatant wrongdoings. By reducing every human act to self-interest and selfserving, the theory does not take a clear stand against so many personal or organizational vices such as corruption, bribery, pollution, gender and racial discrimination.

Utilitarianism: Ethics of Welfare

There are two names associated with utilitarian philosophy; they are Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) who is generally considered the founder of traditional utilitarianism, and philosopher cum classical economist, John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). According to the utilitarian principle, a decision is ethical if it provides a greater net utility than any other alternative decision. Bentham’s principle can be stated thus: “The seeking of pleasure and avoidance of pain, that is, happiness, is the only right and universally desirable end of human action”. Ethics is nothing else than the art of directing the actions of men so as to bring about the greatest possible happiness to all those who are concerned with these actions. It is not merely the agent’s own happiness but that of all concerned. Bentham viewed the interests of the community as simply the sum of the interests of its members. Summarized, the utilitarian principle holds that “An action is right from an ethical point of view if and only if the sum total of utilities produced by that act is greater than the sum total of utilities produced by any other act the agent could have performed in its place”. The utilitarian principle assumes that we can somehow measure and add the quantities of benefits generated by an action and deduct from it the measured quantities of harm that act produced, and determine thereby which action produces the greatest total benefits or the lowest total costs.16

When utilitarianism argues that the right action for a particular occasion is the one that produces more utility than any other possible action, it does not mean that the right action is the one that produces most utility for the person who performs the action. On the contrary, an action is right, as pointed by J. S. Mill, if it produces the most utility for all the persons affected by the action.17

When we try to analyse the utilitarian theory, there are certain inferences and implications of the theory that we must take into account, as otherwise, we will get ourselves totally misled: (i) When utilitarians say that practising the theory will lead to “the greatest happiness for the greatest number”, we should include the unhappiness or pain that may be encountered along with the happiness; (ii) One’s actions will affect other people in different degrees and thus will have different impacts; (iii) Since utilitarians assess actions with regard to their consequences, which cause different results in diverse circumstances, anything might, in fact, be morally right in some circumstances; (iv) Maximization of happiness is the objective of utilitarians not only in the immediate situation, but in the long run as well; (v) Utilitarians agree that most of the time we do not know what would be the future consequences of our actions; (vi) Utilitarianism does not expect us to give up our own pleasure while choosing among possible actions.

Utilitarianism fits in correctly with the intuitive criteria that people use when they discuss moral conduct. For instance, when people have a moral obligation to perform some action, they will evaluate it on the basis of the benefits or harms the action will bring upon human beings. The theory leads to the inevitable conclusion that morality requires the agent to impartially take into account everyone’s interest equally. While assessing the usefulness of utilitarianism in the organizational context it should be understood that it provides standards for a policy action namely, if it promotes the welfare of all, more than any other alternative, then it is good. Second, the theory provides an objective means of resolving conflicts of self interest with the action for common good. Third, the theory provides a flexible, result-oriented approach to ethical or moral decision making.

One major problem with the utilitarian theory concerns the measurement of utility. Utility is a psychological concept and is highly subjective. It differs from person to person, place to place, and time to time. Therefore, it cannot be the basis for a scientific theory.

A second problem concerns the intractability to measurement that arises while dealing with certain benefits and costs. For example, how can one measure the value of life or health?

Another problem of the utilitarian theory concerns the lack of predictability of benefits and costs. If they cannot be predicted, then they cannot be measured either.

The fourth problem concerns the lack of clarity in defining what constitutes ‘benefit’ and what constitutes ‘cost’. This lack of clarity creates problems, especially with respect to social issues that are given different interpretations by different social or cultural groups.

Kantianism: Ethics of Duty

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) is regarded as the most important ethician in the rationalistic school in modern times. One of the basic principles of his ethics is his most famous ethical doctrine that a good will is the only unqualified good. Kant said that for an action to be morally worth it should reflect a good will. By will Kant meant the unique human capacity to act from principle. Contained in the notion of good will is the concept of duty: only when we can act from duty does our action have moral worth. When we act only out of feeling, inclination, or self-interest, our actions—although they may be otherwise identical with ones that spring from the sense of duty—have no true moral worth.

Kant stressed that the action must be taken only for duty’s sake and not for some other reason. For Kant, ethics is based on reason alone and not on human nature. In Kant’s perspective, the imperatives of morality are not hypothetical but categorical. He says that the moral duty that binds us is unconditional. The core idea of his categorical imperative is that an action is right if and only if we can will it to become a universal law of conduct. This means that we must never perform an action unless we can consistently will that it can be followed by everyone.

Organizational Importance of Kantian Philosophy Kantian theory of ethics has adequate relevance to a business organization. Though there are lots of criticisms against Kantian ethics we would consider the positive aspects of his ethics which would be beneficial in organizational decision making. The categorical imperative of Kant gives us firm rules to follow in moral decision making for certain issues, because the result of such actions does not depend on the circumstances or the performer. Lying is an example. No matter how much good may result from the act, lying is always wrong.

Kant introduces an important humanistic dimension to business decisions. In the ethical theories of egoism and utilitarianism humans are considered means to achieve the ends. In the new economic scenario, human beings are sidelined by technological growth and other developments. Kant gives more importance to individuals.

For Kant an action has moral worth only when it is done from a sense of duty. A normal motivation of the kartha is a must to make that action morally right. People in the organization perform certain actions which are beneficial to them thinking that somehow it will be beneficial to the other. The Kantian principle of motivation of a performer of action comes as a correcting instrument to the organization. This is very much relevant for the organization when it takes decisions on ethical issues.

The two formulations of Kant are as follows:

- To act only in ways that one would wish others to act when faced with the same circumstances.

- Always to treat other people with dignity and respect.

To sum up, to Kant, reason is the final authority for morality. Blind beliefs or rituals cannot be the foundation for morality. He emphasized that the basics of ethics are those moral actions that are taken by a sense of duty and dictated by reason.

SOME MORE NORMATIVE THEORIES OF BUSINESS ETHICS

There is a certain amount of confusion in defining business ethics as a field of study between the ethics theorists and those engaged in business. Business ethics is couched in abstract theory by academicians and philosophers. They express their theories in bombastic language and convoluted expressions such as ‘deontological requirements’, ‘hedonistic calculus’ and the like, which make no sense to ordinary businessmen who are neither philosophically inclined nor trained in philosophy. Businessmen express themselves in ordinary language and do not like to deal in abstractions. They are interested in solving the specific problems that confront them directly, rather than indulging in abstractions that look like a road to nowhere.

It is imperative, therefore, that the business ethicist should produce a set of ethical principles that are both lucid and easy to comprehend for business folks, who can place them in the context of their day-to-day business and see whether they have any practical relevance. The search for a down-to-earth theory has led to the evolution of several normative theories that suit specific business environment. “A normative theory of business ethics is an attempt to focus this general theory exclusively upon those aspects of human life that involve business relationship”.18 In simple language, a normative theory is specifically meant to provide men with ethical guidance when they carry on their day-to-day business.

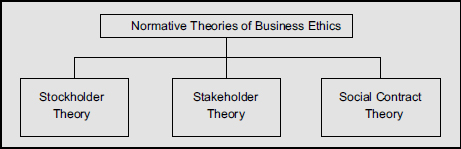

Presently, there are three normative theories of business ethics that have evolved over a period of time. They are (1) stockholder theory, (2) stakeholder theory, and (3) social contract theory (Fig 2.2). Of these three, the oldest and one that has fallen into disrepute with business ethicists in recent times is the stockholder theory, though economists like Milton Friedman, following the footsteps of Adam Smith uphold the line of thinking pursued by the promoters of the theory. To most of the critics, the stockholder theory is an unwarranted hangover from the ‘bad old days of capitalism’. The next theory evolved was the stakeholder theory, which, over the past three decades or so, has gained widespread acceptance among the business ethics community. However, in recent years, the social contract theory has emerged as a strong contender to the stakeholder theory and occupies a pre-eminent position among the normative theories. It needs to be stressed here that each of these three normative theories upholds a distinctly different model of a businessman’s ethical obligations to society, and hence only one of them can be found to be correct. This, of course, will depend upon the sensitivity of the analyst and the manner of his logical interpretation.

Fig. 2.2 Classification of Normative Theories of Business Ethics

The Stockholder Theory

The stockholder theory, also known as the shareholder theory, expresses the business relationship between the owners and their agents who are the managers running the day-to-day business of the company. As per the theory, businesses are merely arrangements in which one group of people, namely, the shareholders advance capital to another group namely, the managers to realize certain ends beneficial to them. In this arrangement, managers (including the Board of Directors) act as agents for shareholders. The managers are empowered to manage the capital advanced by the shareholders and are duty bound by their agency relationship to carry on the business exclusively for the purpose outlined by their principals. This fiduciary relationship binds managers not to spend the available resources on any activity without the authorization from their owners, regardless of any societal benefits that could be accrued by doing so. This obviously implies, as per this line of thinking, that a business can have no social responsibilities.

According to the strict interpretation of the stockholder theory, managers have no option but to follow the dictates of their masters. If the stockholders vote by a majority that their company should not produce any obnoxious product—which in the perception of the managers would be a profitable business proposition—the managers still have to abide by the decision of the owners of the company. This may be a farfetched example, as shareholders who buy stocks of a company to maximize their return on investment may not issue any such direction. There are companies that produce cigarettes, liquor, and pistols and make money to maximize stockholders’ returns. In all such cases, stockholders seem to be happy with the high dividends they get apart from an increase in market capitalization of their stock and therefore, there is no reason for them to issue directions that negate the managers’ actions. The stockholder theory has been succinctly summarized by economist Milton Friedman who asserted thus: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in the activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to stay engaged in open and free competition without deception or fraud”.19

A careful reading of the definitions of the stockholder theory provides us an understanding that it does not give the managers a carte blanche to ignore ethical constraints in the single-minded pursuit of profit. The theory stresses that managers should pursue profit only by all legal, non-deceptive means. A lot of adverse criticism against the theory could have been avoided had the critics appreciated the fact that the stockholder theory did not stress that managers were expected to pursue profit at all costs, even ignoring ethical constraints. The stockholder theory is also associated with the line of utilitarian argument adopted by liberal classical economists. One’s pursuit of profit, goaded by one’s enlightened self interest in a free market economy leads collectively to the promotion of general interest as well, guided as it is by Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’.20 “Invisible Hand” was a term coined by Adam Smith to express the idea that though each individual in his/her economic activities acts in his/her own interest such actions are guided by a sort of ‘invisible hand’ which ensures that they are also to the advantage of the community as a whole. Each individual by pursuing his own self-interest promotes the interest of the society more efficiently than when he really intends to promote it (Adam Smith). Such being the case, it is unwarranted to expect businesses to act directly to promote the common good. Therefore, there is no justification to make a claim that businesses “have any social responsibilities other than to legally and honestly maximise the profits of the firm”.21

Apart from this ‘consequentialist’ line of thinking in support of the stockholder theory, there is another ‘deontological’ argument as well to buttress it. The argument runs like this: “Stockholders provide their capital to managers on the condition that they use it in accordance with their wishes. If the managers accept this capital and spend it to realize some social goals, unauthorized by the stockholders, does it not tantamount to a clear breach of the agreement?”

Criticism of the Stockholder Theory Many business ethicists have been criticizing the stockholder theory for various reasons. It has been described, as part of corporate law that has outlived its usefulness; as one based on a ‘myopic view of corporate responsibility’ and as one that leads to ‘morally pernicious consequences’. Robert C. Solomon22 in his Ethics and Excellence (1992) finds it “not only foolish in theory, but cruel and dangerous in practice” and misled “from its nonsensically one-sided assumption of responsibility to a pathetic understanding of stockholder personality as Homo Economicus”. Many ethicists discard the theory as an outmoded relic of the past.

If so many ethicists wish to dismiss the theory as impractical and even foolish, it is because of its perceived association with the utilitarian supporting argument and neo-classical economists’ faith in the ‘invisible hand of the market forces’. Most modern day ethicists have little faith in laissez-faire capitalism (absolutely uncontrolled free enterprise system) that is beset by market failures. They believe that to the extent the stockholder theory is associated with that type of economic model (laissez-faire capitalism) that cannot be relied upon to secure the common good. The theory itself stands discredited because of its failures.

Another reason why the stockholder theory stands discarded today is because “the contemporary economic conditions are so far removed from those of a true, free market”.23 In today’s world, government—especially in its role in collecting huge taxes and spending the large sums that it earns on various welfare, people-centric, and even defence projects—influences the activities of corporations enormously. Besides, in the modern economies, as a producer the State itself has a significant stake in several utilities and environmental activities. In such a situation, it is very likely that the pursuit of private profit will not truly be productive for the public good.

Another criticism of the stockholder theory is based on a false analogy. It goes like this: if governments of democratic societies have a moral justification to spend the taxpayer’s money for promoting the common welfare of people without taking their consent, then, it might mean, by inference, that businesses are also justified in carrying out social welfare activities without the consent of the shareholders. But then, this is based on a wrong and far-fetched assumption. The very objective of a government, apart from providing political governance, is to provide some basic utility services and also to ensure that the lot of the poor is improved over a period of time. Undertaking welfare measures is one of the generic functions of a government and on occasions such as natural calamities like earthquakes, floods, tsunamis, etc., this may be the most important cause for its existence. Moreover, governments get a mandate from their electors to go ahead with the public welfare activities on the basis of promises made by political parties in their manifestos.

However, in the case of a business organization, promoting social welfare is only incidental to its major function of increasing the profit of the company so as to enhance the long-term shareholder value. They give no undertaking to any shareholder that they would promote public welfare activities when they are formed. In recent times, many socially conscious companies like Tata Steel do seek and get the approval of their shareholders to spend a part of their profit on social welfare activities.

Stakeholder Theory

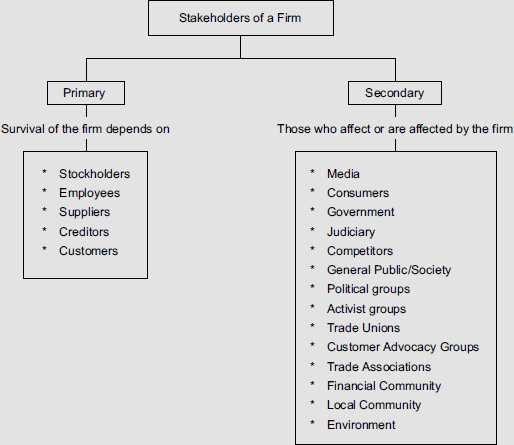

The stakeholder theory of business ethics has a lengthy history that dates back to 1930s. The theory represents a synthesis of economics, behavioural science, business ethics and the stakeholder concept. The history and the range of disciplines that the theory draws upon have led to a large and diverse literature on stakeholders. In essence, the theory considers the firm as an input-output model by explicitly adding all interest groups—employees, customers, dealers, government, and the society at large—to the corporate mix. Figure 2.3 illustrates the different kinds of stakeholders.

The theory is grounded in many normative theoretical perspectives including ethics of care, ethics of fiduciary relationships, social contract theory, theory of property rights, theory of the stakeholders as investors, communitarian ethics, critical theory, etc. While it is possible to develop stakeholder analysis from a variety of theoretical perspectives, in practice much of the stakeholder analysis does not firmly or explicitly root itself in a given theoretical tradition, but rather operates at the level of individual principles and norms for which it provides little formal justification. Insofar as stakeholder approaches uphold responsibilities to nonshareholder groups, they tend to be in some tension with the Anglo-American model of corporate governance, which generally emphasizes the primacy of ‘fiduciary obligations’ owed to shareholders over any stakeholder claims.

However, the stakeholder theory unfortunately carries some sort of an unclear label since it is used to refer to both an empirical theory of management and a normative theory of business ethics, often intermixed and without distinguishing one from the other. In this theory, the stakeholder is defined as anyone who has a claim or stake in a firm. In a wider sense, a stakeholder will mean any individual or group who can affect or is affected by the corporation. Interpreted narrowly, stakeholders would mean “those groups who are vital to the survival and success of the corporation”.24 In its empirical form, therefore, the stakeholder theory argues that a corporate’s success in the market place can best be assured by catering to the interests of all its stakeholders, namely, shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers, management and the local community. To achieve its objective, the corporate would have to adopt policies that would ensure ‘the optimal balance among them’.

Fig. 2.3 Stakeholders of an Organization

As a normative theory, the stakeholder theory stresses that regardless of the fact whether the management achieves improved financial performance or not, managers should promote the interests of all stakeholders. It considers a firm as an instrument for coordinating stakeholder interests and considers managers as having a fiduciary responsibility not merely to the shareholders, but to all of them. They are expected to give equal consideration to the interests of all stakeholders. While doing so, if conflicts of interests arise, managers should aim at optimum balance among them. Managers in such a situation may be even obliged to partially sacrifice the interests of shareholders to those of other stakeholders. Therefore, in its normative form, the theory does assert that corporations do have social responsibilities.

A serious reading of the theory will show that a manager’s fundamental obligation is not to maximize the firm’s profitability, but to ensure its very survival by balancing the conflicting claims of its multiple stakeholders. There are two principles that guide corporations to comply with this requirement. According to the first, called the principle of corporate legitimacy, “the corporation should be managed for the benefit of its stakeholders: its customers, suppliers, owners, employees and the local communities. The rights of these groups must be ensured and, further, the groups must participate, in some sense, in decisions that substantially affect their welfare”.25 The second principle, known as the stakeholder fiduciary principle, asserts that “management bears a fiduciary relationship to stockholders and to the corporation as an abstract entity. It must act in the interests of stakeholders as their agent, and it must act in the interests of the corporation to ensure the survival of the firm, safeguarding the long term stakes of each group”.26

The stakeholder theory has received a wide acceptance among ethicists, perhaps due to the “fact that the theory seems to accord well with many people’s moral intuitions, and, to some extent, it may simply be a spillover effect of the high regard in which the empirical version of the stakeholder theory is held as a theory of management”.27 However, the theory is not beyond reproach and criticism. It has been subject to many criticisms on many perfectly valid grounds.

Criticisms of the Stakeholder Theory The stakeholder theory is often criticized, more often than not as ‘woolly minded liberalism’, mainly because it is not applicable in practice by corporations. Another cause for criticism is that there is comparatively little empirical evidence to suggest a linkage between stakeholder concept and corporate performance. But there are considerable theoretical arguments favouring promotion of stakeholders’ interests. Managers accomplish their organizational tasks as efficiently as possible by drawing on stakeholders as a resource. This is in effect a ‘contract’ between the two, and one that must be equitable in order for both parties to benefit.

The major problem with the stakeholder theory stems from the difficulty of defining the concept. Who really constitutes a genuine stakeholder? There is an expansive list suggested by authors, ranging from the most bizarre to include terrorists, dogs and trees, to the least questionable such as employees and customers. Some writers have suggested that any one negatively affected by corporate actions might reasonably be included as stakeholder, and across the world this might include political prisoners, abused children, minorities and the homeless. However, a more seriously conceived and yet contested list of stakeholders would generally include employees, customers, suppliers, the government, the community, assorted activist or pressure groups, and of course, shareholders. Some writers of the theory opine that where there are too many stakeholders, it is better to categorize them as primary and secondary stakeholders ‘in order to clarify and ease the burden it places upon directors’. Clive Smallman28 says: “The case for including both the serious claimants and the more flippant are rooted in business ethics, in managerial morality and in best practice in business strategy.” Moreover, in his opinion, though the inclusion of a large number of claimants may be well-intentioned, it may not be practical for corporate managers to cater to such a large number of stakeholders.

It is also argued further that the ‘intent of the theory is better achieved by relying on the hand of management to deliver social benefit where it is required’ rather than suggesting a wide range and diversity of stakeholders to cater to. In modern corporations, stockholders are too many and scattered to wield any effective control over them. Hence, they delegate the powers of decision making and execution to their agents, salaried managers through the Board of Director. The agency model specifies mechanisms which reduce agency loss, i.e., the extent to which shareholders are put to loss when the decisions and actions of agents differ from what they themselves would have done in similar situations.

In the assessment of Clive Smallman “The stakeholder model also stands accused of opening up a path to corruption and chaos; since it offers agents the opportunity to divert wealth away from shareholders to others, and so goes against the fiduciary obligations owed to shareholders (a misappropriation of resources)”29. Thus, the stakeholder model of corporate governance leads to corrupt practices in the hands of managements with a wide option (because of too many stakeholders) and also to chaos, as it does not differ much from the agency model, while increasing exponentially the number of principals the agents have to tackle.

The stakeholder theory also can be criticized on the ground that it extends the rights of stakeholders far too much. To draw ethical conclusions from observations of the state of law is as dangerous as to assume that what is legally required should be ethically justifiable. Moreover, to assume that all stakeholders who are impacted by a contract have a moral right to bargain about the distribution of its effects may also lead to an inference that they have a right to participate in the decision making process of business as well, which is absurd.

The Social Contract Theory

The social contract theory is one of the nascent and evolving normative theories of business ethics. It is closely related to a number of other theories. In its most acknowledged form, the social contract theory stresses that all businesses are ethically duty bound to increase the welfare of the society by catering to the needs of the consumers and employees without in any way endangering the principles of natural justice. The social contract theory is based on the principles of ‘social contract’ wherein it is assumed that there is an implicit agreement between the society and any created entity such as a business unit, in which the society recognizes the existence of a condition that it will serve the interest of the society in certain specified ways. The theory is drawn from the models of the political-social contract theories enunciated by thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau. All these political philosophers tried to find an answer for a hypothetical situation as to what life would be in a society in the absence of a government and tried to provide an answer by imagining situations of what it might have been for citizens to agree to form one. “The obligations of the government towards its citizens were then derived from the terms of the agreement”.30 As in normative theory of business ethics, the social contract theory draws much from the averments of these political thinkers.

The social contract theory adopts the same approach as the one adopted by the political theories towards deriving the social responsibilities of a business firm. The theory assumes a kind of society that is bereft of any complex business organization such as the ones we have today. It will be a ‘state of individual production’. They go on to pose such questions as ‘what conditions would have to be met for members of such a society to agree to allow such businesses to be formed?’ The moral obligations of business towards individual members of society are then drawn from the terms of such an implicit agreement between the two. Therefore, the social contract theory is based on an assumed contract between businesses and members of the society who grant them the right to exist in return for certain specified benefits that would accrue to them. These benefits are a result of the functioning of these businesses, both for their own sake and for that of the larger society.

When members of the society give the firms legal recognition, the right to exist, engage them in any economic activity and earn profit by using the society’s resources such as land, raw materials and skilled labour, it obviously implies that the firms owe an obligation to the society. This would imply that business organizations are expected to create wealth by producing goods and services, generate incomes by providing employment opportunities, and enhance social welfare. The concept of ‘social welfare’ implies that the members of the society are interested to authorize the establishment of a business firm only if they gain some advantage by doing so. Such gains occur to them in two distinct ways, namely, as consumers and employees. As consumers, members of the society benefit from the establishment of business firms at least in three ways: (i) business firms provide increased economic efficiency. This they do by enhancing the advantages of specialization, improving decision making resources and increasing the capacity to acquire and utilize expensive technology and resources; (ii) business firms offer stable levels of production and channels of distribution; and (iii) business firms also provide increased liability resources, which could be used to compensate consumers adversely affected by their products and services. As employees, people are assured by “business firms of income potential, diffused personal legal liability for harmful errors, and income allocation schemes”.31

However, business firms do not provide an unmixed blessing. The interests of the public as consumers can be adversely affected by business firms when they deplete the irreplenishable natural resources, pollute the environment and poison water bodies, help to reduce the personal accountability of its members and misuse political power through their money power and acquired clout. Likewise, the interests of the public as employees can be adversely affected by their alienation from the product of their own labour, by being treated as mere cogs in the wheels of production, being made to suffer from lack of control over their working conditions and being subjected to monotonously boring, sometimes damaging and dehumanizing working conditions.

Taking into account these respective advantages and disadvantages, business firms are likely to produce the social welfare element of ‘social contract’ and enjoin that business firms should act in such a manner so as to

- benefit consumers to enable them reach maximization of their wants;

- benefit employees to enable them secure high incomes and other benefits that accrue by means of employment; and

- ensure that pollution is avoided, natural resources are not fast depleted and workers’ interests are protected.

From the justices’ point of view, the social contract theory recognizes that members of the society authorize the establishment of business firms on condition that they agree to function ‘within the bounds of general canons of justice’. Though what these canons of justice mean is not yet a settled issue, there is a general understanding that these canons require that business firms “avoid fraud and deception … show respect for their workers as human beings, and … avoid any practice that systematically worsens the situation of a given group in society”.32

It can be summarized from the above arguments that the social contract theory upholds the view that managers are ethically obliged to abide by both the ‘social welfare’ and ‘justice’ provisions of the social contract. If fully understood, these provisions impose significant social responsibilities on the managers of corporations.

Criticism of Social Contract Theory The social contract theory, like the other normative theories of business ethics, is subject to many criticisms. Critics argue that the so-called ‘social contract’ is no contract at all. Legally speaking, a contract is an “agreement between two or more persons which is legally enforceable provided certain conditions are observed. It normally takes the form of one person’s promise to do something in consideration of the other’s agreeing to do or suffer something else in return”.33 A contract implies a meeting of minds, which does not exist in the so-called social contract. Social contract is neither an explicit nor implicit contract. Those who enter into a business do so merely by following the legal procedures that are necessary under the law of the land and would be shocked if they were told that while doing so, they had entered into a contract to serve the interest of the society in ways that are not specified in the law and that it would have a substantial impact on the profitability of the firm. Therefore, where there is neither a meeting of the mind nor an understanding of the implications of what goes when one gets into a contract, the social contract is more of a fiction than a true contract.

But the proponents of the social contract theory are not unduly put off by such harsh criticisms. They concur with the view of the critics that the core theme of the theory namely, social contract is indeed a fictional or hypothetical contract and proceeds further to state that this is exactly what is needed to identify managers’ ethical obligations. In the words of Thomas Donaldson “If the contract were something other than a ‘fiction’, it would be inadequate for the purpose at hand; namely revealing the normal foundations of productive organisations”. According to social contract theorists, the moral force of the social contract is not derived from the consent of the parties. However, in their view “productive organisations should behave as if they had struck a deal, the kind of deal that would be acceptable to free, informed parties acting from positions of equal moral authority …”34

TEACHINGS OF THE CHURCH

The longing for justice has always been a central theme of the Catholic Church from earliest Biblical times to the present. The work for justice finds its expression from the Gospels. The opening lines of Gaudium et spes of the Second Vatican Council placed the centrality of justice to the Christian calling most vividly in the following words:

“The joys and hopes, the sorrows and anxieties of the women and men of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way oppressed, these are the joys and hopes, the sorrows and anxieties of the followers of Christ”.35

The expression of the Church’s social teaching commenced in the late 19th century, 1891 to be exact, with the encyclical of Pope Leo XIII’s on the Condition of labor(Rerum Novarum). From this modest beginning, Catholic teaching has grown rapidly, representing a rising crescendo of social consciousness and concern in the Church. The social teaching of the Church, based on Christian ethics, comprises sets of principles, guidelines and applications which provide a compelling challenge for individuals as well as corporations in responsible citizenship.

As pointed out, the Church always supports and promotes the welfare of the poor. The Church’s concern for the marginalized is always expressed through her teachings. The less privileged and the marginalized realize the fact that the wealth of the world is in the hands of a few. This emerging awareness of the mass is supported by the Church. People often think how business and ethical teachings of the Church can be related. People always tried to see business without any reference to religion. But now the trend has changed and organizations and institutions relate business with religion and ethics.

This transition is due to the increased importance of ethics in business. The pressing concerns of the society are reflected in the teachings of the Church. ‘Option for the poor’ is the catchword of the Church’s teachings. The Church’s concerns and ethical teachings are found in several papal encyclicals. In the modern organization, sound ethics is a key criterion for success.

Rerum Novarum

Since the late 19th century, there developed a strong tradition of reflective thought on economic issues within the Catholic Church. This concern on economic issues started effectively in May 1891 with the publication of Rerum Novarum, an encyclical of Pope Leo XIII. The central theme of the letter was the relationship between the State, employers and the workers. It strongly laid the foundation for human dignity. It was a revolutionary work, because the Church could change the misconception that she supports the rich and the powerful of the society.

This encyclical directs the State and organizations to perform their duties to the working class. When man is deprived of dignity and equality, he will indulge in unethical practices. There should be mutual support in the society as well as in organizations. This mutual support will help him perform his best for productivity and profit. “The consciousness of his own weakness urges man to call in aid from without. We read in the pages of the Holy Writ: it is better that two should be together than one; for they have the advantage of their society. If one falls, he shall be supported by the other. Woe to him that is alone, for when … It is natural impulse which binds men together in civil society; and it is likewise this which leads them to join together in associations which are, it is true, lesser and not independent societies, but nevertheless, real societies. When the State and organisations perform their duty, there would not be corruption or unethical behaviour in the society.”36

Gaudium Et Spes

Gaudium Et Spes is the Pastoral Documentation of the Church released during the Second Vatican Council in 1965. The burning concern of the Church is that the rapid change and technological advancement makes human beings aware of many facts and that their demands have changed. These aggressive demands have led to so many things that he or she should not have indulged in. To a certain extent this revolution leads to unethical practices. The internal fight of values and developments has changed the basic values of human beings. The social teaching of the Church has developed through addressing new circumstances and conditions of society as they have emerged.

“Today, the human race is involved in a new stage of history. Profound and rapid changes are spreading by degrees around the whole world. Triggered by the intelligence and creative energies of man, these changes recoil upon him, upon his decisions and desires, both individual and collective, and upon his manner of thinking and acting with respect to things and to people. Hence we can already speak of a true cultural and social transformation, one which has repercussions on man’s religious life as well. A change in attitudes and in human structures frequently calls accepted values into question.”37

The Tradition of Catholic Social Thought

The papal encyclicals and pastoral letters that form the foundation of Catholic Social Thought (CST) are moral documents that reflect the concerns of the Church for the lives of millions of human beings as the result of the working of the economies. From the beginning, the focus of CST has been on the problem of poverty and the marginalization of the disadvantaged, first in the industrialized countries and then in the Third World. In the past three decades or so, there has been a growing concern about too much consumption by the rich and inadequate consumption by the poor. This concern was expressed by the Pope Paul VI in his encyclical, Popularum Progressio thus: “the superfluous wealth of rich countries should be placed at the service of poor nations … Otherwise their continued greed will certainly call down on them the judgment of God and the wrath of the poor.” Another aspect of the Church’s concern is the impact of excessive consumption of the earth’s environment. Pope John Paul II in his encyclical Centesimus Annus expressed this concern thus: “Equally worrying is the ecological question, which accompanies the problem of consumerism and which is closely connected to it. In his (or her) desire to have and to enjoy rather than to be and to grow, man (or woman) consumes the resources of the earth and his (or her) own life in an excessive and distorted way” (Para 37). Earlier he has noted: “It is not wrong to want to live better; what is wrong is a style of life which is presumed to be better when it is directed toward ‘having’ rather than ‘being’, and which wants to have more, not in order to be more but in order to spend life in enjoyment as an end in itself” (Para 36).

Thus, the CST reiterated and reinforced by various papal encyclicals advocates that the materialistic-minded consumerism should be substituted by the creation of a more humane future through empowering people to rebuild the values and institutions necessary to morally constrain self interest.38

INDIAN ETHICAL TRADITIONS

India has rich ethical traditions which envisioned in the scriptures of the land like the Gita, the Upanishads, etc. Hindu scriptures speak of the performance of right duty, at the right time in the right manner. The rich Indian tradition has always emphasized the dignity of human life and right to live in a respectful manner. The rich values that once prevailed in India are now disappearing from the mainstream. Indian traditions are copied and followed by Western countries in their social welfare and organizational conduct.

Gandhian Principles

The Gandhian principle of trusteeship is another philosophy on ethics that has received increased importance in the present day world of decaying morals and lack of trust among individuals as well as organizations. The philosophy of trusteeship implies that an industrialist or businessman should consider himself to be a trustee of the wealth he possesses. He should think that he is only a custodian of his wealth meant to be used for the purpose of business. The wealth belongs to society and should be used for the greatest good of all. The trusteeship concept should also be extended to the labour in industry. It does not recognize capital and assets as individual property. This was basically to reduce the conflict between ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’. The origin of the trusteeship principle can be traced to the concept of non-possession detailed in Bhagawad Gita. Gandhiji also advocated Sarvodaya, meaning welfare for all. He was of the firm view that capital and labour should supplement each other. There should be a family atmosphere and harmony in work place. Gandhi’s philosophy of trusteeship has got more relevance in the present scenario. In the recent past, social involvement by business has, for the most part, taken the shape of philanthropy and public charity. This has led to the building of temples, hospitals and educational institutions. A few examples of such activities would include the Birla Temple in Kolkata, the Shree Vivekananda Research and Training Institute set up by Excel Industries in Mandvi which is very much in the spirit of trusteeship; the L&T Welfare Centre in Bombay, the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, and the Voltas Lifeline Express that has been running on Indian tracks for over a decade.

Righteousness as the Way in the Gita

The Bhagawad Gita cites numerous instances of how moral values and ethics can be incorporated in one’s work life. Many of its verses are directly significant for the modern manager who may be confused about his or her direction, and struggling to find an answer to ethical dilemmas. The Lord reiterates that work or karma is the driving force of life, and this work has to be ethical.

Chapter II, Verse 47 says “You have a right to perform your prescribed duty, but you are not entitled to the fruits of action. Never consider yourself the cause of the results of your activities and never be attached to not doing your duty”.39 This is the important message of Gita that the performer of the action has only to perform the prescribed duty and not indulge in the result of the action. If the worker leaves the result of the work to the Lord, on the realization that the result is beyond his control, then he can be serene forever, because he is not worried of the result whether it is good or bad. This teaching of the Gita draws one’s attention to Nishkama Karma.

In the organizational context too when one is only worried of the result, he or she is likely to fall into improper activities. On the other hand, if one is ready to do his or her duty to the maximum of one’s ability and able to set aside the result, he or she will be an ethical person in the organization.

Chapter II, Verse 56 says “One who is not disturbed in mind admits the threefold misery or elated when there is happiness and who is free from attachment, fears and anger, is called a sage of steady mind.”40

A steady mind, another mental state, is desirable in one’s work life, to retain one’s integrity in the work one does. A steady mind gives you the right attitude and right direction. Detachment is that quality which enables the individual not to accept anything for personal gratification. In the organizational context, this quality is very much valued. Personal desires and conflicting interests end up in unethical practices.

Lord Krishna’s promise, in the seventh and eighth verse of Chapter IV of the Gita is that, whenever evil dominates, the Lord takes an avatar to set right the situation and re-establish the Dharma.41 Translated, these verses mean as follows:

“Yada yada hi dharmasya glanir bhavati bharata

abhyuthanam adharmasya tatamanam srujamy aham42

Whenever and wherever there is decline of Dharma and ascendance of Adharma, then, O scion of the Bharata race! I manifest (incarnate) Myself in a body.43

Paritranaya sadhunam vinashayacha dushkritam

dharma samsthapanarthaya sambahvami yuge yuge”44

For the protection of the good, for the destruction of the wicked, and for the establishment of Dharma, I am born from age to age.45

Business and Islam

For Islam, all principles covering business emanate from the Holy Quran, as they are explained and amplified in the Hadith (collection of the Prophet’s sayings). In Islam, there is an explicit edict against the exploitation of people in need through lending them money at interest and doing business through false advertising.

Mohammed, the last Prophet and Messenger, was very much involved in business before he was chosen by God. He was involved in trade from his early age and had widely travelled and had rich experience in business.

The Prophet laid stress on honesty and truthfulness in business. He said “God shows mercy to a person who is kind when he sells, when he buys and when he makes a claim”.46 His teachings cover a wide range of business and economics. Dr. Muzammil H. Siddiqi47 in his article ‘Business Ethics in Islam’ enumerates the following major business principles drawn from the teachings of Prophet Mohammed.

- No fraud or deceit: The Prophet said, “When a sale is held, say—there’s no cheating.” (Al-Bukhari, 1974)

- No excessive oaths in a sale: The seller must avoid excessive oaths in selling an article: The Prophet ordained: “Be careful of excessive oaths in a sale. Though it finds markets, it reduces abundance.” (Muslim, 3015)

- Need for mutual consent: Mutual consent is necessary: “The sale is complete when the two part with mutual consent.” (Al-Bukhari, 1970)

- Be strict in regard to weights and measures. “When people cheat in weight and measures, their provision is cut off from them.” (Al-Muwatt, 780) He told the owners of measures and weights: you have been entrusted with affairs over which some nations before you were destroyed.” (Al-Trimidhi, 1138)

- The Prophet was very much against monopoly: “Whoever monopolises, he is a sinner.” (Abu Da’ud, 2990)

- Free enterprise: According to the Prophet, the price of the commodities should not be fixed unless there is a situation of crisis or extreme necessity.

- Hoarding is forbidden: Hoarding the commodities in order to increase their prices is forbidden.

- Forbidden transactions: Transaction of things that are forbidden is also forbidden, such as intoxicants.

The Prophet Mohammed ordained that businesses should promote ethical and moral behaviour and should follow honesty, truthfulness and fulfilment of trusts and commitments, while eliminating fraud, cheating and cut-throat competition.

Shariah and Interest on Capital

Shariah bans the taking of interest, because according to this law, investors can make profits only from business based on exchange of assets and not on money. As per the law, bankers sell sukuk or Islamic bonds only by the use of property and other assets so as to generate income which would be equal to the interest they would be paying on conventional debt. As per the shariah, the money thus gained cannot be used to finance gambling, guns or alcohol. Such assets managed under Islamic rules will be $2.8 trillion by 2015, according to the Islamic Financial Services Board, an association of Central Banks based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. According to Zafar Sareshwala, Managing Director of Parsoli Investments: “It is the religious requirement of a Muslim to be invested; rather it is unislamic to hold money. Interest is forbidden, but sharing risk and responsibility, that is, sharing profit and loss is acceptable. Equity investing is wholly acceptable under Shariah as long as it is in companies compliant with the Shariah rules”.48 This implies that Muslim investors invest only in a portfolio of ‘clean stocks’. They do not invest it stocks of companies dealing in alcohol, conventional financial services (banking and insurance), entertainment (cinemas and hotels), tobacco, pork meat, defence and weapons. Sectors such as computer software, drugs and pharmaceuticals and automobile ancillaries are all Shariah compliant. Currently, there are more than 800 Shariah compliant stocks on the exchanges.

SUMMARY

‘Ethics’ and ‘morality’ though used interchangeably are two different concepts. ‘Morality’ according to philosophers refers to human conduct and values and ‘ethics’ is the study of a set of principles that define human character or behaviour in relation to what is morally right or morally wrong. The principles do not lead to a single course of action but provide a means of evaluating and deciding among competing options.

Ethics is considered a normative study, that is, an investigation that attempts to reach normative conclusions. Ethics, in business relates to human conduct in a business organization. Ethical theories in business include the consequentialist and non-consequentialist normative theories and the normative themes of egoism, utilitarianism, and Kantian ethics. There are also, other non-conse-quentialist normative themes: duties, moral rights, and prima facie principles.

Egoism asserts that an act is morally right if and only if it best promotes an egoist’s (person, group or organization) long term interests. According to the utilitarian principle an action is ethically right only if the sum total of utilities produced by that act is greater than the sum total of utilities produced by any other act that could have been performed in its place. In the organization, the usefulness of the utilitarianism is assessed by the policy decision that if it promotes the welfare of all more than any other alternative, then it is good. One of the basic principles of Kantian ethics is that a good will is the only unqualified good. Kant introduces an important humanistic dimension to business decisions which is to behave in the same way that one would wish to be treated under the same circumstances and to always treat other people with dignity and respect. Each of these theories has been subjected to criticism and has not been easily adopted by the business organizations.