Chapter Thirteen

Ethics and Indian Business

IMPACT OF GLOBALIZATION

India’s capital market is acquiring a global image with the gradual opening of the country’s economy since 1991. The increasing importance of foreign portfolio investment in the securities market and the drastic reduction in import tariffs have exposed Indian companies to foreign competition. Till recently, participants in the Indian capital market could, to a large extent, afford to ignore what happened in other parts of the world. Share prices largely behaved well, as if the rest of the world just did not exist for them. However, now the Indian capital market responds to all types of external developments, such as US bond yields, the value of the Euro or for that matter any other currency, the political situation in the Gulf, or the new iron, steel, textiles, or petrochem capacity in China.

The almost five decades old shackles are broken and in desirable tweaking of cliché, we are giving new meaning to that old slur—the Hindu rate of growth. The India story is creating a brand-new narrative that investors are queuing up to be part of. We are poised to match world leadership in services by gaining in manufacturing sectors such as auto components and pharma. The world seems to have discovered India’s vast potential that has kindled in the country fresh hopes. India’s comparative advantage in the world has changed for the better according to Bimal Jalan, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, because of four factors: (i) in-house skills in technology, software and other knowledge domains; (ii) the integration of financial markets, the practically free flow of capital into the corporate sector; (iii) the change of technology, aided by a great reduction in government control, which has enabled the corporate sector to restructure itself—thus paving the way for emergence of entrepreneurship and acquisition of new companies here and abroad; and (iv) a strong foreign exchange position.1

In short, the Indian capital market is on the threshold of a new era. Gradual globalization of the market will mean the following changes:

- The market will be more sensitive to developments that take place abroad.

- There will be a power shift as domestic institutions are forced to compete with foreign institutional investors (FIIs) who control the floating stock and the Global Depository Receipts (GDR) market.

- Structural issues will come to the fore with a plain message: ‘Either reform or despair’.

- The individual investor in his or her own interest will refrain from both primary and secondary markets; he or she will be better off investing in mutual funds.

ROLE OF SECURITIES MARKET IN ECONOMIC GROWTH

In the words of G. N. Bajpai, former SEBI Chairman: “It is the securities market which reflects the level of corporate governance of different companies and accordingly allocates resources to best governed companies. If the securities market is efficient, it can penalise the badly governed companies and reward the better-governed companies”.2 A well-functioning securities market is a sine qua non to sustained economic growth. Several studies made by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and those made by research scholars, have revealed that there exists a relationship between development in the securities market and economic growth. A disciplined market avoids investment on low-yielding enterprises and continuously monitors the performance of these enterprises through share prices in the market.3

The securities market facilitates the globalization of an economy by providing connectivity to the rest of the world. This linkage helps the inflow of capital into the country’s economy in the form of portfolio investment. Besides, a strong domestic stock market performance also enables well-run local companies to raise capital abroad. Some Indian companies like Reliance, Infosys, Tata Steel and many others have, for instance, successfully tapped markets abroad and secured huge amounts—a prospect that was unthinkable about a decade back in the foreign market, or even now in the domestic market. This practice will, in turn, help raise the efficiency of domestic corporations once they are exposed to international competitive pressures and the necessity of not only surviving amidst competition but also performing well for their continued survival.

The existence of a domestic securities market will deter capital flight from the domestic economy by providing attractive investment opportunities locally. Economists also point out that a developed securities market successfully monitors the efficiency with which the existing capital stock is deployed, and thereby significantly increase the average rate of return on investment. Having established the importance of the securities market for promoting corporate governance standards, and equally important economic development of a country, let us turn to Indian securities market.

PHENOMENAL GROWTH OF INDIAN CAPITAL MARKET

At the time of Independence, there were very few corporations in India because of the absence of a corporate culture. However, in the post-Independence era, there was an appreciable growth in the capital market, especially after 1985.The Indian capital market by 1990 was one of the fastest growing markets in the world. The number of companies listed on the stock exchanges, close to 6,000, was the second highest after the United States and by 1995 the number rose to 8,593. Presently, there are more than 10,000 listed companies in the country’s 25 stock exchanges. Shareholding public is estimated at 20 million. Value of securities traded increased from US$ 5 billion in 1985 to US$ 21.9 billion in 1990, which was the fourth largest amongst the emerging markets of the world. Market capitalization increased from US$ 14.4 billion in 1985 to US$ 31.6 billion in 1990, US$ 65.1 billion in 1992, US$ 80 billion in 1993 and exceeded US$ 120 billion in 1998–1999. Turnover ratio (total value traded as percentage of average market capitalization) rose to 65.9. Resources raised from the capital market by the non-government public limited companies increased from Rs 7,063.4 million to Rs 52,668.0 million in 1982–1983. Indian corporations raised domestic debt and equity totalling US$ 6.4 billion equivalent in 1994–1995 and US$ 8.5 billion in 1996–1997. Indian companies have also been raising substantial sums in the international capital markets—US$ 4.7 billion in 1994–1995, US$ 2.3 billion in 1995–1996 and US$ 4.7 billion in 1996–1997. There has been a recent dramatic shift towards increased issuance of debt instruments. The equity-debt split was 97 per cent in 1994–1995 and by 1996–1997, it was 23 to 77 per cent.

It is quite evident that the overall growth of Indian stock markets has been phenomenal since independence. Indian stock markets have not only grown in number of exchanges, but also in number and capital of listed companies. The remarkable growth after 1985 was due to the favourable government policies towards security market industry.

However, the functioning of the stock exchanges in India suffered from many weaknesses such as long delays in transfer of shares, issue of allotment letters and refund, lack of transparency in procedures and vulnerability to price rigging and insider trading. To counter these shortcomings and deficiencies and to regulate the capital market, the Government of India set up the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in 1988. Initially, SEBI was set up as a non-statutory body, but in January 1992 it was made a statutory body. SEBI was authorized to regulate all merchant banks on issue activity, lay guidelines, supervise and regulate the working of mutual funds and oversee the working of stock exchanges in India. SEBI, in consultation with the government, has taken a number of steps to introduce improved practices and greater transparency in the capital market in the interest of the investing public and the healthy development of the capital market.

NATURE OF THE INDIAN CAPITAL MARKET

The Indian capital market, like the money market, is known for its dichotomy. It consists of an organized sector and an unorganized sector. In the organized sector of the market, the demand for capital comes mostly from corporations, government and semi-government organizations apart from household savings, institutional investors such as banks, investment trusts, insurance companies, finance corporations, government and international financing agencies.

The unorganized sector of the capital market on the supply side consists mostly of indigenous bankers and moneylenders. While in the organized sector the demand for funds is mostly for productive investment, a large part of the demand for funds in the unorganized market is for consumption purpose. In fact, many purposes, for which funds are very difficult to get from the organized market, are financed by the unorganized sector. The unorganized capital market in India, like the unorganized money market, is characterized by the existence of multiplicity and exorbitant rates of interest, as well as lack of uniformity in their business transactions. On the other hand, the activities of the organized market are subject to a number of government controls, and supervised by the market regulator, SEBI. Though efforts were initiated to bring the unorganized sector under some sort of regulatory framework or at least to bring in some discipline such as registration, these were not successful and this segment is by and large outside effective government control.

The organized sector has been subjected to increasing institutionalization. The public sector financial institutions account for a large chunk of its business.

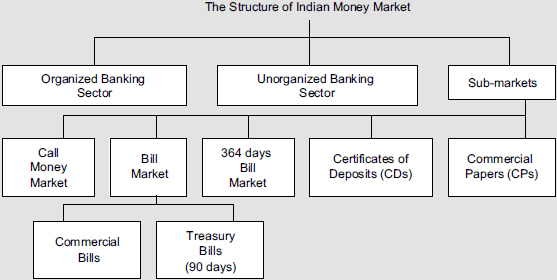

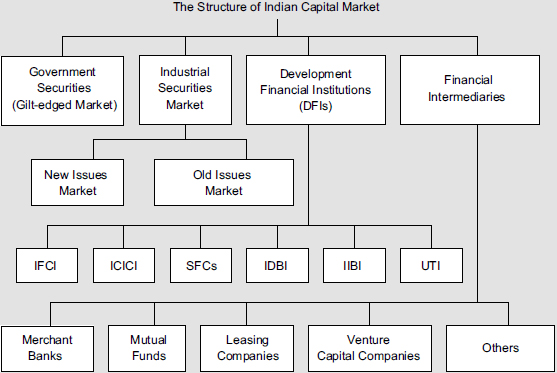

Charts 13.1 and 13.2 show the structures of the Indian money market and the Indian capital market, respectively.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE INDIAN CAPITAL MARKET

The Indian capital market, as pointed out earlier, has undergone many significant changes since independence. The important factors that have contributed to the development of the Indian capital market are given below.

Legislative Measures

Laws such as the Companies Act, the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act and the Capital Issues (Control) Act had empowered the government to regulate the activities of the capital market with a view to assure healthy trends in the markets, protect the interest of the investor, ensure efficient utilization of the resources, etc.

Establishment of Development Banks and Expansion of the Public Sector

Starting with the establishment of the Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI), a number of development banks have been established at the national and regional levels to provide financial assistance to enterprises. These institutions today account for a large portion of the industrial finance.

Chart 13.1

Chart 13.2

The expansion of the public sector in the money and capital markets has been accelerated by the nationalization of the insurance business and the major part of the banking business. The Life Insurance was nationalized in 1956 and the General Insurance in 1972. The Reserve Bank of India was nationalized as early as 1949. The Imperial Bank, the then largest commercial bank in India, was nationalized and established as the State Bank of India in 1955. The 14 major private commercial banks were nationalized in 1969. With the nationalization of the six leading private banks in 1980, over 90 per cent of the commercial banking business came to be concentrated in the government sector.

Thus, an important aspect of the Indian capital market is that a large part of the investible funds available in the organized sector is owned by the government. The new economic policy has changed the trend, and brought in the private sector in a large measure.

Growth of Underwriting Business

There has been a phenomenal growth in the underwriting business, mainly due to the public financial corporations and the commercial banks. After the elimination of forward trading, brokers have begun to take on underwriting risks in the new issue market. In the last one decade, the amount underwritten as percentage of total private capital issues offered to public varied between 72 and 97 per cent.

Public Confidence

Impressive performance of certain large companies such as Reliance Industries, Tisco and Larsen & Toubro encouraged public investment in industrial securities. Booms and the consequent declaration of hefty dividends in the mid-1980s boosted investor confidence.

Increasing Awareness of Investment Opportunities

The improvement in education and communication has created more public awareness about investment opportunities in the business sector. The market for industrial securities has become broader.

Capital Market Reforms

A number of measures have been taken to check abuses and to promote healthy development of the capital market. The enactment of the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992 and the establishment of the SEBI as a capital market regulator are important milestones in the process of reforms in this sector.

DEFICIENCIES IN THE INDIAN CAPITAL MARKET

The Indian capital market suffers from the following deficiencies:

- Lack of diversity in the financial instruments

- Lack of control over the fair disclosure of financial information

- Poor growth in the secondary market

- Prevalence of insider trading and front running

- Manipulation of security prices

- Existence of unofficial trade in the primary market, prior to the issue coming into the market

- Absence of proper control over brokers and sub-brokers

- Passive role of public financial institutions in checking malpractices

- High cost of transactions and intermediation, mainly due to the absence of well-defined norms for institutional investment.

In a planned economy like the one we had prior to liberalization, when the stock exchanges performed a residual role, these deficiencies did not matter much. On the other hand, in a market-driven economy towards which we are moving, capital market is expected to perform multifarious and facilitative functions, such as

- Privatization: A greater role for the private sector implies a large demand for equity finance.

- Equity market should enable investors to diversify their wealth across a variety of assets.

- Stock markets should perform a screening and monitoring role.

- A financial system that functions well requires that the whole financial sector functions efficiently.

In view of its importance, the continuing shortcomings point to the inability of the market to function at a level that is expected. Besides, many of the unethical practices such as price-rigging and insider trading arise from the deficiencies found in the Indian capital market. Too often, the 25 million small investors find that their hard-earned money is being stolen by fly-by-night operators and their confidence in the private corporate sector to safeguard their interests is rudely shaken. The 2005–2006 initial public offer (IPO) scam is the most recent instance of how investor confidence is dented because of the vulnerability of the system. To what extent the Indian capital market regulator, SEBI, tackles these scams and issues arising out of them are discussed in Chapter 12.

MAJOR INDIAN SCAMS4

Various deficiencies in the Indian capital market, misgovernance, greed, corruption, inefficiency and market manipulations have resulted in a series of scams in the country. Some of the major scams that seriously dented investors’ confidence are listed below.

- 1992—Harshad Mehta Scam (Market Manipulation): This first stock market scam was one which involved both the bond and equity markets in India. The manipulation was based on the inefficiencies of the settlement systems in the Government of India (GoI) bond market transactions. A pricing bubble came about in equity market where the market index went up by 143 per cent between September 1991 and April 1992. The amount involved in the crisis was around Rs 54 billion.

- 1993—MNCs’ Efforts at Consolidation of Ownership: There were a number of reported cases in which several transnational companies were found to consolidate their ownership by issuing equity allotments to their respective controlling groups at steep discounts to their market price. In this preferential allotment scam investors alone lost around Rs 5,000 million.

- 1993–1994—Vanishing Companies Scam: Between July 1993 and September 1994, the stock market index zoomed by 120 per cent. During this boom 3,911 companies that raised over Rs 250,000 million vanished or did not set up projects as promised in their prospectuses. This scam occurred because during the artificial boom, hundreds of obscure companies were allowed to make public issues at large share premia through high sales pitch of questionable investment banks and grossly misleading prospectuses.

- 1994—M. S. Shoes Affair (Insider Trading): The dominant shareholder of M. S. Shoes East Ltd, Pawan Sachdeva, took large leveraged positions through brokers at both the Delhi and Mumbai stock exchanges to manipulate share prices prior to a rights issue. When the share prices crashed, the broker defaulted and BSE shut down for three days as a consequence. The amount involved in the default was about Rs 170 million.

- 1995—Sesa Goa (Price Manipulation at BSE): This was caused by two brokers who later failed on their margin payments on leveraged positions in the shares. The exposure was around Rs 45 million.

- 1995—Rupangi Impex and Magan Industries Ltd (Price Manipulation): The dominant shareholders implemented a short squeeze. In both the cases, dominant shareholders were found to be guilty of price manipulation. The amount involved was Rs 5.8 million in the case of Magan Industries Ltd and Rs 11 million in the case of Rupangi Impex Limited.

- 1995—Bad Delivery of Physical Certificates: When anonymous trading and nationwide settlement became the norm by the end of 1995, there was an increasing incidence of fraudulent shares being delivered into the market. It has been estimated that the expected cost of encountering fake certificates in equity settlement in India at the same time was as high as 1 per cent.

- 1995–1996—Plantation Companies Scam: This scam saw Rs 500,000 million mopped by unscrupulous and fly-by-night operators from gullible investors who believed plantation schemes would yield huge returns.

- 1995–1998—Mutual Funds Scam: This scam saw public sector banks raising nearly Rs 150,000 million by promising huge returns, but all of them collapsed.

- 1997—CRB Scam Through Market Manipulation: C. R. Bhansali, a chartered accountant, created a group of companies, called the CRB Group, which was a conglomerate of finance and non-finance companies. Market manipulation was an important focus of activities for this group. The non-finance companies routed funds to finance companies to manipulate prices. The finance companies would source funds from external sources using manipulated performance numbers. The CRB episode was particularly important in the way it exposed extreme failure of supervision on the part of RBI and SEBI. The amount involved in CRB scam was Rs 7 billion.

- 1998—Market Manipulation by Harshad Mehta: This was another market manipulation episode engineered by Harshad Mehta. He worked on manipulating the share prices of BPL, Videocon and Sterlite in collusion with their managements. The episode came to an end when the market crashed due to a major fall in index. Harshad Mehta did not have the liquidity to maintain his leveraged position. In this episode, the top management of the BSE resorted to tampering with the records in the trading systems while trying to avert a payment crisis. The president, executive director and a vice-president of BSE had to resign due to this episode. This episode also highlighted the failure of supervision on part of the SEBI. The amount involved was of Rs 0.77 billion.

- 1999–2000—The IT Scam: During this 2-year period, millions of investors lost their entire investments, duped by firms that changed their names to sound infotech. But when the unsustainable dotcom bubble burst, the hapless investors realized that their stocks were not even worth the paper on which they were printed.

- 2001—Price Manipulation by Khetan Parikh: This scam, known as the Ketan Parekh scam, was triggered off by a fall in the prices of IT stocks globally. Ketan Parekh was seen to be the leader of this episode, with leveraged positions on a set of stocks called the K-10 stocks. There were allegations of fraud in this crisis with respect to an illegal badla market at the Calcutta Stock Exchange and the banking scam.

- 2004—Dramatic Slide in the Stock Market: Between 14 and 17 May, there was a dramatic fall in the scrips of Reliance, Hindustan Lever, State Bank of India, Infosys and ONGC. On 17 May, Sensex fell by 11.14 per cent. SEBI had found that a dozen players, whose names were not divulged, were responsible for the price rigging and had put them on notice. Earlier on May 14 also, the stock market crumbled. On that day, in Sensex, the largest loser was State Bank of India with a dip of 14.77 per cent. In all these falls, the market capital worth millions of rupees was wiped out, and consequently investors’ confidence was badly shaken.

- 2005—Demat Scam: After a great deal of damage was done to retail investors, who lost opportunities to get their due allotments in several IPOs between 2003 and 2005, SEBI investigated 105 such cases and unearthed full details leading to the scam. It was found that certain entities had cornered shares reserved for retail investors by opening thousands of fictitious demat accounts, with active collusion of the depositary participants in order to increase their chances of allotment. After allotment, these benami holders transferred these shares to their financiers, who in turn sold them soon after making sizeable profits. It was the small investors who lost out because of this unscrupulous practice. This has happened notwithstanding the rule that multiple applications are not allowed.

This series of scams has cast a shadow over the credibility of SEBI, and its capacity to create a safe and sound equity market.

CAN UNETHICAL BEHAVIOUR BE AVOIDED?

There seems to be no magical formula or cure to make people act ethically in business here or elsewhere. In a book (1996) entitled Ethical Dimensions of Leadership, the authors Kanungo and Mendonca quote a survey which concludes that “other things being equal” criminal activity is higher among the top management who have undergone a formal training. It is also suggested that “management educators do not seem to provide adequate training and formation in business ethics”.5 Moreover, it does not help to have managers who are intelligent and technically competent if they are arrogant, self-centred, emotional and compulsive. Apart from an individual’s ethical qualities, it is also equally important that the organization’s moral environment is conducive. The authors quote Paine who insists that an unethical practice generally involves “the tacit, if not explicit, cooperation of others and reflects the values, attitudes, beliefs, language and behavioural patterns that define an organisation’s operating culture”.6 We have enough evidence of this assertion in the work ethics and culture of Enron, WorldCom and Andersen. In India, as we have seen earlier, there had been several such ‘rogue’ corporations that acted unethically and cheated their investors, employees, suppliers, consumers and the government, notwithstanding the existence of a plethora of rules and regulations to check these immoral practices.

REASONS FOR UNETHICAL PRACTICES AMONG INDIAN CORPORATIONS

For a long period, the Indian public has considered business people as corrupt, untrustworthy and profiteering. The government’s policy of encouraging the public sector, while treating the private sector in a step-motherly manner, the licensing policy that made them resort to unethical practices such as applying for licenses in benami names, liaisoning with politicians and bureaucrats through drink and debauchery, greasing their palms to get favours, pre-empting competitors, not producing goods after obtaining licenses with a view to creating artificial scarcity and charging premium prices for their products are some of the factors that brought the Indian business community a very bad name. The governments, both at the centre and states, especially the former are more than responsible for this unhealthy and unethical state of affairs.7 The Industrial Licensing Policy was the villain of the piece. The corrupt and partisan manner in which it was administered resulted in time and cost runs of industrial projects and huge losses to the license seeking industrialists. Moreover, hundreds of licenses and clearances had to be obtained from as many public authorities. The private sector had no alternative but to quicken the process through ‘speed money’. Those who were unethical flourished faster, others grew in fits and starts. Unethical and corrupt practices ruled the roost, and hardly anyone who indulged in these sordid games felt penitent or tried to correct himself. ‘If you cannot beat them, join them’ was the rule of the game.

If corporate managements indulged in unethical practices, a recent survey found that corporations themselves are often victims and susceptible to fraud risk. A KPMG survey “India Fraud Survey Report 2006” revealed that the Indian financial sector is highly susceptible to fraud risk. According to the survey, the preparedness of Indian corporations to address fraud is very low. Just 24 per cent of the respondents have the relevant physical and logistic access controls to tackle such serious issues. The risk is greater in the banking, insurance, mutual funds and asset management companies with 23 per cent of the respondents believing them to be the most vulnerable to malfeasance. A total of 17 per cent of the respondents put non-banking financial companies (NBFCs)/investment banks on the high risk. Information, communication and entertainment sector follows in the pecking order. With the boom in the financial sector and organizations facing various kinds of challenges, the risk faced by corporations is increasing several fold. The report identified different perpetrators who caused the fraud. A total of 18 per cent of the respondents believed that employees posed the maximum perceived threats to organizations operating in financial sectors, while in cases of organizations operating in the BPO sector, 36 per cent believed that employees posed the maximum threat. However, there is a silver lining seen on the issue. In recent times, there is a reduced tolerance to fraud and non-ethical behaviour. There is a clear shift from reactionary measures in combating fraud to proactive measures in mitigating the fraud risk.8

Another area where Indian corporations are subject to fraud risk is from cyber mafia. In a recent survey by IBM, a greater number of companies (44 per cent) listed cyber crime as a bigger threat to their profitability than physical crime (31 per cent). The cost of cyber crime stems primarily from the loss of revenue, loss of market capitalization, damage to brand and loss of current customers, in that order. The IBM Global Survey (3000 respondents, of whom 150 CIOs were from India) identified the new source of cyber crime as organized criminal gangs possessing technical sophistication, who are replacing lone hackers. Besides, threats to corporate security are now coming from inside the organization. The survey also reveals greater awareness and proactive measures being taken by Indian corporations to combat cybercrime.9

BUSINESS ETHICS IN INDIA TODAY

Why this upsurge of interest in ethics today? It is interesting to trace the crests and troughs traversed by the concepts of ethics and social responsibility of business in India. In a recent international survey of levels of honesty in government and business, countries were ranked by giving them marks out of 10 for their honesty: Singapore was number one in the world with 9.7 marks while India was seventh out of 10 with 3.1 marks! Clearly our country’s ethical image badly needs furnishing.10

- In 1992, XLRI conducted a highly successful conference of company directors on business ethics. It was attended by a hundred participants and the proceedings were published under the title Corporate Ethics, the first book on the subject in India.

- Till recently, Indian B-Schools did not think it fit to introduce business ethics as a course in M.B.A. programmes. XLRI was the only management school which had ethics as a three-credit core course for the last five years. Now the IIMs too have introduced ethics, at least as an elective.

- We are accustomed to flattering ourselves with the belief that we are a highly ethical nation, certainly more so than most others. Yet in 1964, Gunnar Myrdal, in his celebrated work Asian Drama, noted that during the days of British rule only petty corruption at lower levels was known in the Indian administration, whereas since Independence corruption had spread throughout the system and indeed begun from the very top. It is this, says Myrdal, which is holding India back. India would now probably have become another Asian tiger, if corruption was not endemic in the country.11

With the onset of globalization and the huge foreign institutional investment in India, the Indian corporations can no longer turn a blind eye to the needs of the hour. The writing on the wall for the erstwhile unethical corporations is very clear—‘Clean up your acts or perish for want of investment’. It is inherently in the corporations’ own interest that they shape up to be better corporate citizens. The time has come for them to be more prudent in incorporating ethics into their systems. An ethical corporate can contribute to serve the community around it directly and indirectly, in many ways. Furthermore, a corporate expects others in the line of business to be ethical in their dealings, else the entire trust upon which business is conducted will be lost. Business cannot be conducted in an environment of mutual distrust and suspicion, and hence it is in its own interest that a corporate conducts itself ethically.

Ethical business must be adhered to by the entire business community. Mere lip service to the cause would undermine the trust, which is the very foundation for conducting business. Agreeing to be ethical and then reneging on the commitment would lead to inconsistency in the business environment. A trustworthy company that has over the years earned a good reputation and the goodwill of people through its ethical conduct stands a much greater chance of attracting more business than the others. An ethical corporate not only attracts more business but also gains the respect of its employees, shareholders, creditors and the society at large.

Ethical business has only helped organizations to improve their brand equity and image. A good example is that of the famous pharmaceutical giant, Johnson & Johnson. The way it conducted itself in the wake of the Tylenol drug controversy was laudable. It had to withdraw massive stocks of drugs from various pharmacies and druggists and suffered huge loss running up to US$ 100 million in the wake of six deaths caused by the use of cyanide-laced Tylenol capsules. The effort that went into recalling all the stocks from the retail outlets was mind-boggling. Ultimately, Johnson & Johnson came out triumphantly with its image enhanced even further when the public realized that it was not its fault. Johnson & Johnson was lavished with praises and the grateful public gave it an overwhelming support. Johnson & Johnson regained its standing and also made up for its losses in a very short time. Nearer home, when it was pointed out to the late Mr J. R. D. Tata that competitor companies were growing much faster than the century-old House of Tatas, he answered that the Tatas believed only in growth that is based on ethics, equity and socially responsible behaviour. He once observed in an interview that the major reason for his admiration of Jamshedji Tata was “his sense of values, sterling values, which he imparted to this group. If someone were to ask me, what holds the Tata companies together, I would say it is our shared ideals and values as a corporate citizen, which we have inherited from Jamsedji Tata”.12

CORPORATIONS IN INDIA CANNOT AFFORD TO BE ETHICAL13

When questioned about unethical practices, many companies claim that the conditions in India are not conducive to allow them the luxury of being completely ethical. Thousands of underhand deals are struck everyday and go unreported. There is hardly a company which has not at sometime or the other been either involved or suspected of some foul play. Even companies that started off with intentions to do business in an ethical manner have had to compromise their principles due to the highly politicized and bureaucratic business environment in the country. Growing corruption, increasing disparity between people and rapidly reducing profit margins add to the woes of organizations that want to be ethical.

Indian companies face two types of corrupt practices: (i) political corruption in which money is paid in return for favours done by politicians, and (ii) administrative corruption. In the early days of Independence, companies had to grease the palms of bureaucrats to make them do things they were not supposed to do, but now corruption has graduated to such an extent that companies have to bribe bureaucrats to make them do things they are supposed to do. Examples of this sort of corruption include ‘gifts’ to the factory inspector, boiler inspector, Pollution Control Board inspectors, and assessors for customs, excise, income tax, sales tax and octroi. It is this administrative corruption, which most companies claim to be unavoidable most of the times.

A study on the ethical attitudes of Indian managers conducted by Arun Monappa (1977) reported that business executives listed three major obstacles to ethical behaviour, namely: (i) company policies; (ii) unethical industry climate; and (iii) corruption in government. Company policies tend to be unethical due to socio-cultural environment, and get reinforced because of the sense of frustration and helplessness that comes from the prevalent and all pervading unethical environment.

With regard to the socio-cultural reasons underlying the tendency of Indian corporations to be unethical are, the low priority accorded to business ethics in newly formed democracies as it seems there are more urgent demands that have to be dealt with first.14 The imperatives of the day-to-day survival for businessmen and the law-makers make it not to be unduly concerned about the ethical and moral implications of their actions. This situation has been sharpened by the opening up of the economy wherein Indian corporations find it increasingly difficult to compete in a dog-eats-dog kind of global markets. Another factor that has contributed to the lack of ethical ethos and behaviour is the country’s aspiration to build a strong and economically powerful nation in a short time.

The other factors affecting ethical dilemmas of Indian corporations are (i) socio-cultural factors such as the sense of hospitality (not inviting a business associate could be construed as impolite; and once invited, showering him or her with gifts is an accepted custom) and reciprocity (‘You gave me a license with which I make money, and there is nothing wrong in sharing a part of it with you’); (ii) the psychological fear of losing jobs; (iii) lax government structures and regulations; (iv) sanctions and discriminations in a society that can be offset with accumulation of wealth by fair or foul means; there are innumerable instances where criminals and bootleggers have, after amassing wealth through foul means, acquired high social standing; (v) uncertainties and fears about the future; (vi) strong family traditions and laws of inheritance in which parents want to leave substantial assets to their progeny; (vii) overall scarcity of resources and the difficulty of amassing wealth through normal and legitimate means; (viii) an inequitable and scorching tax system (almost an unbelievable 97.75 per cent in terms of both direct and indirect taxes at the highest bracket in the 1960s and 1970s) which discourage hardworking and honest tax-payers and lead them to bribe tax-collectors; (ix) a belief that business and ethics are irreconcilable; and (x) a tendency to adopt an easy option when confronted with difficult ethical choices—‘Well, if I can’t beat them, I may as well join them’ becomes a natural choice.

Lea gives another explanation to the deviant ethical behaviour found among corporations in developing societies. Transition from subsistence culture to the commercial enterprise of capitalistic culture can result in a moral chaos in which behaviour falls short of ethical expectations. In traditional sub-cultures, rituals govern life. These rituals are insufficient behavioural guides in capitalism, which increases individual autonomy and responsibility, and generates surpluses and wealth. Rapid economic growth leads to the development of a distorted understanding of capitalism and growth, in which money power, survival and profitability at any cost are considered as the primary goals of any business. The manifestation of this idea is very apparent in India, and especially so in the case of some famous ‘rags to riches’ stories.15

The need to adapt to the unethical environment is so strong that even large multinationals, setting up facilities in India have been unable to avoid cutting corners. In their eagerness to capture the Indian market and beat the competition, many companies have grossly broken their stringent codes of conduct, which in the West would be unthinkable. This was apparent when a major portion of the top management of a leading fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) multinational in India were removed on grounds of violation of the ethical code of conduct. However, there was no visible effort on the part of the company to own up or reverse some of the unethical actions performed by its erstwhile employees.

SOME UNETHICAL ISSUES IN INDIA

As we discuss business ethics from the Indian perspective, it becomes to look at ethical violations in their various forms that are rampant in the country. Right from the Harshad Metha scam till the insider trading of L&T versus Reliance, we see unethical practices taking place even in reputed organizations. Researches and studies show that several ethical issues such as bribery, coercion, deception, theft, unfair discrimination are faced by any organization. Some of these are dealt in detail below.

Bribery

Bribing is still commonly practised in India today and is considered to be part of conducting everyday business. According to a Times of India opinion poll,16 76 per cent rated ‘business’ as a corrupting force, right after ‘politicians and ministers’, which 98 per cent considered to be corrupt. Bribes (euphemistically called ‘speed money’, ‘oiling the wheels’ or ‘greasing the palm’), have to be paid for almost anything a company wants to do, whether it is expanding, obtaining a contract, or exporting or importing goods. Most government officials receive low remuneration and expect bribes, to improve their personal state. High levels of bureaucracy support these practices. The law also has many loopholes, which companies find ways to bypass. Most Indian business people argue that the practice of bribery is a fault of the system rather than of the people living and working in it. They even use this as an excuse for their acceptance of this practice. Until recently there have been few efforts by companies to curb bribery.

Bribery is a manipulative method where one buys the power or the influence of other person in order to satisfy his or her selfish need. Bribes create a conflict of interest between the person receiving bribe and his or her organization. This conflict would result in unethical practices. When somebody is bribed for something his or her thinking and actions are oriented towards his or her personal goals. This direction towards personal goals always results in a mismatch between the interest of the organization and that of the individual. When there is a mismatch between the goals, naturally he or she cannot be loyal to the organization, and in turn, he or she will indulge in unethical practices. Bribery undermines market efficiency and predictability, thus ultimately denying people their right to the minimal standard of living. “Bribery does more than destroy predictability; it undermines essential social and economic system”.17

For example, companies like Boeing and General Electric (GE) have well-formed policies to deal with this issue. These policies of the company check the employees from indulging in such practices. The statement of GE is worth mentioning, “No matter how high the stakes, no matter how great the ‘stretch,’ GE will do business only by lawful and ethical means. When working with customers and suppliers in every aspect of our business, we will not compromise our commitment to integrity”.18 Likewise, Boeing is categorical with regard to this issue. The ethical business guidelines states that the company will deal fairly and impartially with all its suppliers and customers. “A business courtesy may never be offered under circumstances that might create the appearance of impropriety or cause embarrassment to Boeing or the recipient. An employee may never use personal funds or resources to do something that cannot be done with Boeing resources. Accounting for business courtesies must be in accordance with approved company procedures and practices”.19,20 Closer home, the vision statement of Larsen & Toubro is worth recalling. It says: “All marketing personnel will adhere to the highest standards of personal and corporate integrity and thereby maintain and promote our reputation as an outstanding company with which to do business”.21

Corruption

With so much corruption prevalent in the country any Indian citizen is forced wonder what has happened to the country’s leaders. There seems to be no doubt that the principal culprits responsible for corroding the ethical sense of the industrial and political leaders of India are first, the type of governance ‘We, the people’ gave ourselves and second, the type of economy that was imposed on us. First, we chose an electoral process in which the spending of millions to win a seat was forbidden, yet necessary. This single factor made corruption and black money a substantial part of the electoral process, and therefore, of government and industry. Thousands of faceless bureaucrats and venal politicians decided every aspect of the economy: what should be produced, how much, by whom, at what price, with what technology and raw materials. Thus economic decision making was taken away from economists, end producers, from farmers and industrialists and handed over to politicians and bureaucrats. As a result, a forest of permits, licenses and controls contributed to the infamous ‘license raj’ which successfully dwarfed, stunted and made a ‘bonsai’ out of the economy of this enormous country.

Transparency International which prepares the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) every year, placed India 71st among 102 countries it surveyed in 2002 and estimated that by way of corruption, officials at various levels siphon of an astounding sum of Rs 267,680 million every year. Education, health, power, telephone, railways, land and building administration, judiciary and the public distribution system mostly contributed to this vast sum of corruption22 (see Box 13.1).

Bribery is what contributes to corruption and takes the forms of (a) demand and acceptance of money by officials for doing what they are expected to do; (b) stealing public funds; (c) demanding and accepting ‘commissions’; (d) offering bribes, especially for undue and out-of-turn favours; and (e) use of public office for personal pecuniary gains. In India, almost every citizen would have paid at some point of their life bribes or ‘speed money’ not only to make officials do what they are not supposed to do, but also to make them do what they are appointed to do. Bribery has become such an inalienable part of one’s life, that it has acquired the attributes of the Almighty—Omnipresent, Omnipotent, and Omniscient! With the passing of the Right to Information Act (see Appendix) and the efforts of the civil societies India is assumed to be marginally less corrupt in 2006 than in 2005.23

BOX 13.1 INDIA 30TH IN GLOBAL BRIBE INDEX

In a global recognition of a different kind, India has been ranked as the worst performer by Transparency International on its global bribe payers index, which is based on the propensity of companies from the world’s 30 leading exporting countries in bribing abroad. Transparency, the worlds’ corruption watchdog said overseas bribery is still common among the world’s export giants despite the existence of international anti-bribery laws, with companies from emerging exports powers—India, China and Russia—being the worst performers.

India has been ranked at the 30th position in the Transparency International 2006 Bribe Payers Index (BPI), with a score of 4.62. A score of 10 indicates a perception of no corruption, while zero means corruption is seen as rampant. Switzerland has been ranked at the top slot with a score of 7.81, followed by Sweden, Australia, Austria and Canada at the top five positions on the index. The US and UK have been ranked at tenth and sixth positions, respectively. Transparency International said Switzerland has managed a leading score of only 7.8, which is far from perfect. This indicates there might be variations here but there are no real winners, it added. According to the report, businesses from India, China and Russia, who are at the bottom of the index, have the most propensity to pay bribes.

BPI’s 2005 data shows that leading exporters are undermining the development with their dirty business practices overseas, while the foreign bribery by emerging export powers is ‘disconcertingly high.’ Companies from the wealthiest countries have been ranked in the top half but they still routinely pay bribes, particularly in developing economies, it added. “In the case of China and other emerging export powers, efforts to strengthen domestic anti-corruption activities have failed to extend abroad”, the report said. “Bribing companies are actively undermining the best efforts of governments in developing nations to improve governance, and thereby driving the vicious cycle of poverty”, said Transparency International Chairperson, Huguette Labelle.

“It is hypocritical that Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)-based companies continue to bribe across the globe, while their governments pay lip-service to enforcing the law,” Transparency International CEO David Nussbaum said. “The enforcement record on international anti-bribery laws makes for short and disheartening reading”, he added. “Domestic legislation has been introduced in many countries following the adoption of the UN and OECD anti-corruption conventions, but there are still major problems of implementation and enforcement”, he added.

The index has been prepared on the basis of responses of more than 11,000 business people in 125 countries polled in the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey 2006. The watchdog said India consistently scores worst across most regions and sub-groupings, while China is the world’s fourth largest exporter and ranks second to last in the index.

Transparency International chairperson said, “With growing influence comes a greater responsibility that should constitute opportunity for good”.

Source: Press Trust of India, 2006, India 30th in Global Bribe Index, 5 October.

With regard to the causes of corruption, most of them are well known. (1) Wherever there is a scarcity of goods or services or when there is a demand-supply disequilibrium in the government-controlled economy, consumers have to pay a premium over and above the prices fixed for goods and services. (2) Licenses, controls and the system of on-the-spot inspections are common causes of corruption. (3) Too many laws, rules and regulations which are too difficult to comply with, or approvals and sanctions to be obtained from officials are also fertile grounds for corruption. (4) Bribes are paid to low-paid babus to speed up things or clear files. (5) Electors are corrupted by politicians who extract their pound of flesh from every one else when seized of power; for instance, a World Bank report24 states that winning candidates in India on an average, spent over 30 times the stipulated amount for a Lok Sabha seat in the 1999 general elections. While the campaign ceiling for a Lok Sabha seat has been re-pegged at Rs 2,50,000, the average winner spent about Rs 83,00,000 in the 1999 general elections. The report attributed the staggering expenses to the growth of the multi-party system in which “competition in tight races has encouraged a free-for-all to outspend opponents to win”.25 (6) Senior bureaucrats join politicians to get kickbacks from the public and contractors. (7) Regularization of illegal violations and protection extended to those who have fallen foul of law are also grounds for getting bribes. (8) The unholy value system in society, which is willing to accept bribery and corruption as a way of life is also a feeding ground for corruption. “Failure of the society to create an institutional structure to tackle cases of corruption, especially in high places, creates a feeling of helplessness about corruption among masses”.26

Black Money

Black money refers to the illegal earning made by people, whether they are businessmen or others, in violation of legal channels of earning income. Black money generation is a consequence of the system of controls, permits, quotas and licenses. Considerable amount of black money was also generated in the administration of controls and licenses.

- Obviously, bribes had to be paid in unaccounted cash. To get such large amounts of unaccounted cash, taxes of all kinds were evaded, exports under-invoiced and imports over-invoiced.

- Corruption is like a cancer eating into the very vitals of the social, political and economic life of the country. Since black money is so widespread and has become socially acceptable, it has corrupted every profession: teachers, doctors, lawyers, the judiciary, and spread throughout every system of the country, from top to bottom.

The genesis of the so-called black economy in India can be traced to the Second World War when the country had to export to the theatres of war in Europe several essential commodities, which resulted in severe shortages within the country leading to controls and rationing. It was thought that this phenomenon of acute shortage of essential commodities would come to an end once the war was over. However, it continued even after Independence, especially after the advent of planning. A mixed economy, a predominant role to the public sector and a license and inspection raj system to monitor the private sector provided a fertile ground for the continued existence of black money or parallel economy.

With the rapid expansion of economic activity, the magnitude of the so-called quasi economy tended to grow and proliferate to such an extent that it has begun to play “a dominant role in moulding state policies, in changing the structure and composition of output, and in promoting a class which derives its maximum source of power from black money”,27 resulting in the establishment of a parallel economy. The parallel economy is so huge and the growth of rigged deals so alarming that it poses often a serious threat to the growth and stability of the official economy. Another ramification of the growth of black incomes is the accentuation of inequalities in income and wealth and the breeding of a new class of ‘black’ rich in a society which is already harshly stratified (Box 13.2). “The inequalities are no longer below the surface. The conspicuous consumption of the new ‘black’ rich, their vulgar display of pomp and opulence, their unlimited accessibility to finance, their nest-eggs in various places and countries, their influence in important places, all these are now common knowledge”.28

The generation of black money comes through various sources: (1) under-reporting of output or sales or over reporting of the costs or misclassification of personal expenses by manufacturing and trading enterprises (about 10 per cent of the amount of GDP); (2) black income generated in relation to capital receipts on sale of assets, that is, the registered value of property often represents only 60 per cent of its true value; (3) through leakages in fixed capital formation in the public sector; estimates show that a range of 10–15 per cent of the cost of construction, plant and machinery are siphoned off as black income; (4) black income generated by corporations in the private sector to the extent of 10–15 per cent in relation to their investments by way of kickbacks from suppliers and contractors; (5) black income generated in exports amounting to a minimum of 10 per cent of the free on board (FOB) value of ‘traditional exports’; (6) substantial quantity of black income generated through over-invoicing of imports by the private sector and sale of import licenses.

BOX 13.2 BLACK MONEY AND THE RICH

A classic example of what the newly wealthy and filthy rich are capable of showcasing their wealth was reported in all newspapers and flashed across the country widely by the newspapers and electronic media in early June 2006. Bibek Moitra, private secretary of the slain political leader, Pramod Mahajan (who himself was a poor school teacher turned politician, given to flashy and lavish lifestyle and known to be capable of raising hundreds of millions of rupees for his party) organized a party, took out currencies of Rs 15,000 from his wallet, asked his newfound friends to buy some ‘stuff’, and when brought in, he joined Pramod’s son, Rahul, who in turn took out a Rs 500 currency, rolled it with cocaine and snorted it as the money was burnt to ashes. This was a sordid drama enacted in a country, wherein more than one-fourth of the population lives below poverty line and scarcely manages to have one meal a day!

Several studies of black income generated in our economy show an astounding amount of the so-called ‘unaccounted income’. Global estimate of our black income ranged from Rs 99.58 to 118.7 billion in 1975–1976 and from Rs 203.62 to 236.78 billion in 1980–1981. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance and Black Money estimated that the amount of black money circulating in the country was an astounding Rs 3000 billion in 1994–1995 at 1980–1981 prices or Rs 11,000 billion at the current prices. The black income that was less than 10 per cent of the country’s GNP up to 1975–1976 began to leapfrog at much faster rate later. According to one estimate, it was about 45 per cent of GNP in 1983–1984 and rose to an astounding 51 per cent in 1987–1988.29

The generation of black money, its circulation and the creation of a parallel economy have very serious impact and repercussions on the economy: (1) Generation of black money reduces the revenue to the State exchequer as a consequence of tax evasion. Besides, “while the tax-paying public finds its own income falling, the non-tax paying public is having a free run on swelling concealed incomes, thereby adding a new dimension to the problem of inequality of incomes, and wealth”.30 (2) With a lot of black money at their disposal businessmen indulge in conspicuous consumption, leading to a ‘demonstration effect’* on all classes of people. “As a consequence, the consumption pattern is tilted in favour of the rich and elite classes, at the cost of encouraging the production of articles of mass consumption”,31 distorting the very objectives of economic planning. (3) Black money encourages investment in jewellery, diamonds and bullion with its adverse effect on economic growth by reducing availability of capital for investment. (4) Black money laundering has helped for diversion of resources in the purchase of luxury houses and real estates. Black money owners have been instrumental in pushing land prices to astronomical heights. Middle-class people have been denied their rights to own houses; investments are diverted to luxurious mansions, and government loses by way of tax revenues, when these buildings are gifted away. (5) The ‘black liquidity’ built up due to the accumulation of black money in the form of cash, bullion, precious stones, etc. thwarts government attempts to combat inflation. Efforts made by the government to check excess demand through credit control measures and rationing are hence rendered fruitless. This adversely affects control of supply of money and becomes a threat to price stability. (6) Black money is transferred abroad through hawala transactions in violation of foreign exchange regulations by under-invoicing of exports and over-invoicing of imports. Thus, the country becomes a channel of exporting its badly needed capital and hampers its economic growth. (7) Black money has created an army of musclemen, touts, brokers, liaison men, advocates and accountants, for its protection, proliferation and expansion. (8) It has, through its clout, corrupted our political and economic systems. The Wanchoo Committee, known as the Direct Taxes Enquiry Committee (1971) observed: “It is, therefore, no exaggeration to say that black money is like a cancerous growth in the country’s economy, which if not checked in time, is sure to lead to its ruination”.32

Coercion

“Coercion is forcing a person to act in a manner that is against his or her personal beliefs”.33 It is an external force or a man-made constraint created that compels the other to act against his free will. The authority of the person who demands such activity plays an important role. It may be in the form of a blackmail to an individual in an organization. It may be in the form of a threat of blocking a promotion or loss of a job. This sort of unethical practice in the organization will beget more unethical behaviour from the individual. For example, the Tylenol tampering case of Johnson & Johnson was perpetrated with an intention of damaging the image of the company and forcing it to incur great financial expenses in correcting the problem.34

Insider Trading

This is one form of misuse of official position of an individual in the organization. Here, the employee leaks out certain confidential data to outsiders or to insiders, which in turn, ruin the reputation of the company. Insider trading may lead to the bad performance of the company in the long run. If the employees trade confidential matters, the competitor may intervene and make use of the opportunity. Inside traders often defend their actions by claiming that they do not injure anyone. It may be true with nonpublic information, but certain moral concerns arise because of this act. For example, reports in the media show that such practices are taking place in reputed companies at the top-level management.

Tax Evasion

There are major unethical practices of tax evasion. Many large corporations hire the services of professional tax consultants to take advantage of loopholes in the law and evade taxes to the extent possible. The reason they attribute for such behaviour is the prevalent rate of corporate taxation, which is very high. In fact, this has generated a parallel economy in spite of government’s continuous endeavours to channelize this money towards legitimate development purposes.

The well-known tax consultant Dinesh Vyas has written about an incident that indicates J. R. D. Tata’s commitment to ‘tax compliance’.

On one occasion, a senior executive of a Tata company tried to save on taxes. The chairman of the company took him to J. R. D. Mr Vyas explained to J. R. D.: “But sir, it is not illegal”. J. R. D. asked, softly, “Not illegal, yes. But is it right”? Mr Vyas has written that no one had ever asked him that question during his decades of professional work. Mr Vyas later wrote in an article: “J. R. D. would have been the most ardent supporter of the view expressed by Lord Denning: ‘The avoidance of tax may be lawful, but it is not yet a virtue”.35

Conflicts of Interest

Even the most loyal employees can find that their interests conflict with that of the organization. Sometimes this clash of goals and desires can take a serious form. In an organization, conflict of interest arises when employees at any level behave with private interests that are substantial enough to interfere with their job or duties. This would result in the individual’s interests acting against the interest of the employer. Conflicts of interest are morally perturbing, especially when it causes an employee to act to the detriment of the organization. Great men like J. R. D. Tata had been trying all their lives to reduce such conflicts of interest in the work place. J. R. D.’s strong point was his intense interest in people and his desire to make them happy. To J. R. D. ethics included gratitude, loyalty and affection. He would write to his former colleagues even after they retired.36

J. R. D. was inspired by Jamsedji Tata in all his dealings with workers. In the 1880s and the 1890s, Jamsedji ensured adequate ventilation for his employees at the workplace and conferred several other benefits on them such as accident insurance and a pension fund. These measures were taken during a period when capitalist exploitation was taken for granted. J. R. D. was a strong believer in workers having a say in their welfare and safety. He was instrumental in the founding of the personnel department and two pioneering steps taken by Tata Steel: a profit-sharing bonus and a joint consultative council. Tata Steel has enjoyed peace between management and labour for 70 years.37

Pollution

The unethical practice of pollution affects society and population to a major extent. The high levels of pollution due to the indiscriminate and improper disposal of effluents by industries have rendered the world a highly unsafe place for progeny. In his last years J. R. D. Tata was very conscious of the environment and the industry’s part in spoiling it. The J. R. D. Tata Centre for Eco-techonology at the M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation was created in furtherance of his desire. It is gratifying to note that of late several leading Indian corporations have taken it as an article of faith to promote a safe and congenial environment—Tata Steel, ITC, NTPC, Pricol Industries, to name only a few.

WHY SHOULD INDIAN BUSINESS BE ETHICAL?

What is the basic reason for being ethical in business dealings? Is it because ethics pays? This may not always be true, especially in the short run. Moreover, when one adopts ethics because it pays, it is not really ethics but expediency. There are four reasons why business should be ethical.

- Ethics responds to the best in us: Most people want and even need to be ethical in their private lives and also in their business affairs. People want to work in an organization they can respect and be publicly proud of.

- Values create credibility for the company with the public: People will purchase their goods and subscribe to their issues if companies are seen to be ethical. Examples are the products of Tatas and Larsen & Toubro, which people tend to buy without hesitation.

- Values give management credibility with its employees: Only perceived moral uprightness and social concern bring employee respect. The management of such companies are held in high esteem by their employees. In such companies, attrition rate will be low.

- Values help better decision making: Hard decisions which have been studied from both ethical and economic angle are more difficult to make, but they will stand up against all odds, because the good of the employees, the public interest, and the company’s own long-term interests would have all been taken into account.

With the globalization of business, monopolistic market condition or State patronage for any business organization has become a thing of the past. A business organization has to compete for a share in the global market on its own internal strength, in particular on the strength of its human resource, and on the goodwill of its stakeholders. While its state-of-the-art technologies and high level managerial competencies could be of help in meeting the quality, cost, volume, speed and breakeven requirements of the highly competitive global market, it is the value-based management and ethics that the organization has to use in its governance. This would stand it in good stead to enable it to establish productive relationship with its internal customers and lasting business relationship with its external customers. It is for these reasons that value based management and practice of ethics have become imperatives in corporate governance now, and in the foreseeable future. If values are the bedrock of any corporate culture, ethics are the foundation of authentic business relationships.

STUDIES ON ETHICAL ATTITUDES OF MANAGERS

Professor Arun Monappa of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, with the assistance of the All India Management Association undertook a study of ethical attitudes of Indian managers (Box 13.3). He worked out a questionnaire based largely on the model developed by Rev. Fr. Baumaart S. J. Loyola University of Chicago, author of Ethics in Business and administered it to 115 participants. The study of Arun Monoppa concludes: The Indian manager seems to have set high ethical standards for himself. If he has not put his belief into action, it is because the environment has not influenced him into doing so. The outstanding feature was the influence wielded by the company policy and management on employees. Herein lies the key to the problem of raising the ethical level in industry. Decision makers in industry and government should consider this aspect seriously while formulating plans and policies.38

The result of a survey on ethical attitudes of Indian managers by Sadri, Dastoor and Jayashree (Box 13.4) which was more elaborate and broad-based than the one by Monappa more or less conforms to the conclusions drawn by him. There are certain areas where the findings of the surveys contradict each other. In Monappa’s findings, it was shown that older managers demonstrated a greater deal of ethical awareness than the younger ones. The findings of Sadri et al.39 reveal that as managers grew in age and position, their commitment to ethics waned. Both the studies tend to conclude that though Indian managers seemed to swear by their personal moral standards, they are not in a position to stick to them in the organizational context, especially when pressure is wrought on them by their bosses. It only shows a lack of strength of character and inability to stand up and be counted upon under pressure.

BOX 13.3 SURVEY FINDINGS ON ETHICAL ATTITUDES OF INDIAN MANAGERS (1976)

Monappa’s study was an attempt to find “the reactions of managers at the middle management and senior executive levels. What are his reactions to the dilemma? How does he feel, caught between his obligation to his company, to his employees and to the consumers? How does he resolve these conflicts? The data that has emerged, to say the least, provides food for much thought”. The study consisted of 115 managers and executives belonging to middle (61) and senior level (54) management and working in medium to large companies, in different age groups (20–55 years) with diverse religious backgrounds. The study was the first of its kind in India and the findings were very revealing.

A majority of the managers believe in good ethics, but extraneous factors such as the following have an impact:

Managers are pressurised to act contrary to their conscience due to:

- Company policy

- Cut-throat competition

- Rules and regulations

“Buying business” through gifts, gratifications of illegal nature, personal favours etc. work in their minds raising ethical dilemmas.

They do spend time in considering ethical implications of their actions.

Company policy and decisions of the Board get precedence over personal code of conduct.

Personal influence of superiors, through whom company’s policies are transmitted, tend to bend the views of managers.

Dishonest methods employed by competitors in business and the general unethical climate tend to dampen the ethical enthusiasm of an average manager.

Corruption among public: “Beginning-muddle-no end” theory—public servants, red tapism, nepotism and favouritism present obstacles on the path of ethical approach.

Attitudes and reactions of older business managers to situations demonstrated a greater deal of ethical awareness than that of younger managers.

The size of the company had no influence on ethical decision making.

Managers were dissatisfied with the idea that profits should be the ONLY guideline for a businessman in the decision making process.

Formal education or/and training did not seem to have stimulated the desire to act honestly.

Religious guidance did not appear to have any district effect on the ethical approach.

Certain areas were more prone to encourage unethical practices than other businesses: For example, construction, engineering, R & D, banking investment and insurance.

Most managers welcomed a “code of conduct” and felt that it would help in improving the ethical climate in the business world.

The respondent managers also felt that the management of the company rather than others would be the authority best suited to enforce the code.

Source: Arun Monappa (1977), Ethical Attitudes of Indian Managers—All India Management Association, New Delhi. Reprinted with permission from AIMA.

However, the differences in the methodology adopted, the size and the number of respondents and also the divergence in times especially with the latter period being a time wherein enormous changes have taken place in the economy, may account for the small variations in the findings of the two surveys about the ethical attitudes of Indian managers.

Cross-cultural empirical studies that have so far been conducted focus on investigating the relationship between culture and business ethics, and particularly in testing the hypothesis that there are cross-cultural differences in business-ethical beliefs, perceptions, attitudes and behaviour of people involved or associated with business. Many cross-cultural studies confirm the hypothesis that culture influences one’s ethical perception, attitude and behaviour. Studies also indicate that culture plays a role in the way people across cultures identify situations posing ethical problems. However, not all empirical cross-cultural studies confirmed the influence of culture on business leaders’ ethical beliefs, perceptions, attitudes and behaviour. Several studies did not support the hypothesis that there were differences in business ethical attitudes and conduct across cultures. On the other hand, they seem to support the convergent hypothesis that individuals, irrespective of cultures, are forced to adopt the industrial attitudes to survive in today’s industrialized society, which is becoming increasingly homogeneous due to rapid communication channels and globalization of business. Studies on the influence of culture on business decisions have always produced mixed results. They show that cultures are not totally different from one another. While Monappa’s study showed that Indian managers by and large tend to be ethical in their business dealings, a more elaborate and comparative study by Christie et al. (Box 13.5) suggests that culture has a strong influence in the decision making of Indian business managers as it has in the cases of Americans and Koreans.40

BOX 13.4 SURVEY ON ETHICAL ATTITUTES OF INDIAN MANAGERS BY SADRI, DASTOOR AND JAYASHREE (1993)

In a survey on the ethical attitudes of Indian managers, six thousand questionnaires were administered to respondents from NITIE and XLRI. Of the 3291 received and analysed, 786 questionnaires were rejected as they were either incomplete or improperly filled. Only 2505 questionnaires with acceptable responses were segregated and analysed. The following are the breakup of the industry-wise responses:

The study concentrated on one central question: How do Indian managers act when faced with an ethical dilemma? And in seeking an answer to this question many findings unfolded shedding light on the managerial ethics within the corporate sector of Indian industry.

Findings

In examining the conditions under which managers take decisions involving an ethical dilemma, seven factors were brought out by the investigation. The factors along with the meanings attributed to them by the researchers are as follows:

1. Bribery: Lining the pockets or granting favours to statutory officials as well as competitor’s agents, employees or clients for the purpose of realizing corporate objectives.

2. Piracy: Acquiring technological know-how, information of competitor’s pricing and costing policies and procedures, and infringing copyright/patents of established companies and of foreign brands.

3. Blackmail: Practices involving the continuation of an unethical practice with an implied or unimplied threat that stopping such a practice will ‘rock the boat’ and cause a human relations problem.

4. Unfair Practices: Dumping sub-standard products in the market knowing well that they are either a health hazard or of little value for the price paid, just because the chance/cost of rejection is to be avoided.

5. Social Damage: Not taking cognizance of the fact that pollution is a social evil or that poisonous waste disposal is injurious to public health, just because the cost of scientific waste disposal is too high or the technology required for it is too difficult to obtain.

6. Workers’ Safety: Not giving enough importance to the health of the worker employed, in the greed to make quick corporate profits e.g., not insisting that the correct safety gear is worn while working or that atmospheric/ noise pollution on the shop floor is reduced. And, safety gear is provided often to safeguard the employer from having to pay damages to the injured workman rather than out of a genuine concern for the well being of the employee.

7. Corruption: Feathering one’s own nest, building one’s own ‘territory’ and lining one’s own pockets at the expense of the company e.g., not insisting on vendor rating or having ‘above board’ practices for accepting and opening tenders and quotations.

In terms of influences on the decision making process the scores, in order of being most in importance, are as follows:

1. |

Generally accepted practices in the organisation |

26% |

2. |

Behaviour of co-managers |

24% |

3. |

Society’s moral environment |

17% |

4. |

Ability to take a position and justify it |

11% |

5. |

Fear of getting exposed |

10% |

6. |

Lack of social conscience |

7% |

7. |

Personal greed |

3% |

8. |

Lack of a formal policy |

2% |

9. |

Economic necessity |

0% |

This goes to demonstrate that the Indian manager is not as motivated by the need to amass wealth as he or she is to get social or peer group acceptability. This finding shows that there is enough economic security, but not enough gumption to stand up for what one believes in. This shows that the managers adopt a kind a sophistry to justify their actions. And, while this may facilitate ‘team building exercises’, it does not facilitate individual initiative, promote creativity or encourage innovation.

Many respondents (89.3 per cent) felt that it was possible to improve the ethical standards and the concomitant behaviour of managers. But in the in-depth interviews everyone seemed to be saying, I am ethical but the situation forces me to be otherwise. The proverbial buck did not stop anywhere.

In the written responses it was shown 77.29 per cent felt that managers get more unethical as they climb up the corporate ladder. This supports the earlier finding that it is not the economic need per se that motivates a manager to be unethical but the added responsibility of an extended family system, as the manager advances in age, which might create the need to be unethical. This particular point was stressed in the interviews and it was found that managers became unethical as they grew more powerful in the organisation.

When the respondents were asked who they would consult in the event of an ethical dilemma, the responses in rank order of preference were as follows:

1. |

Boss/Colleagues |

31% |

2. |

Professional peers outside the organisation |

24% |

3. |

Friend |

21% |

4. |

Teacher or mentor |

16% |

5. |

Rule book |

8% |

Once again, the responses show that the Indian manager is in search of a sophistry, an acceptance by the peer group, by friends and mentors when confronted with an ethical dilemma.

When asked which one single factor would dissuade the manager from making an unethical decision the ranked scores were as follows:

1. |

Inability to discuss openly and freely |

36% |

2. |

Loss of status at work place |

21% |

3. |

Effect on business interest |

16% |

4. |

Fear of loss of face in society |

15% |

5. |

Fear of getting caught |

12% |

Yet again, the sample shows that the manager adopts the Praxis view in making decisions involving an ethical dilemma.

Outcome of the survey

According to the authors, the survey revealed the insecurity of the manager to take independent decisions based on his/her beliefs. This breeds sycophancy and a cadre of mediocrity. They are good in the art of pleasing the boss or feeling his or her pulse before opening their mouth, with a view to currying flavour.