Command and Control for Healthcare

Introduction

In the last chapter, we discussed a variety of what might be called “mainstream” command and control models, including both the Incident Command System (ICS) and the Incident Management System (IMS), and examined how they operated. While these models may work exceedingly well in the community setting, there are fundamental realities which challenge their ability to be fully effective in a hospital or healthcare setting.

Hospitals, for very valid reasons, require their own, specialized, Command and Control systems. Disasters often have both immediate and long-term effects on both population health and on health delivery, in both the developed and the developing world.1 That being said, the community’s Command-and-Control systems do represent the context in which the Command-and-Control systems of the hospitals and healthcare providers will be operating. As a result, while the systems used in healthcare remain specialized, they must also remain fully integrateable and inter-operable with the mainstream systems.

This chapter will examine the reasons why specialized Command-and-Control models are required in healthcare. We will also examine two healthcare-specific Command-and-Control models: the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS) and the Healthcare Emergency Command and Control System (HECCS). The two models will be examined in detail in both normal and special operations, and their features and also relative strengths and weaknesses will be discussed. Finally, these models will be examined in terms of their interoperability, both with each other, and with the mainstream command and control models likely to be in use in the community.

Upon completion of this chapter, the student should be able to discuss the rationale for the use of specialized Command-and-Control models in the hospital and healthcare sector, and why the use of “mainstream” Command-and-Control models often fail to meet the needs of this sector. The student should be able to compare and contrast the structures, features, and operating systems of both the HICS model and the Healthcare HECCS model and discuss the relative strengths and weaknesses of each. Finally, the student should be able to discuss how facilities using these two models may have their models successfully integrated, and also how to integrate the use of either model with the “mainstream” Command-and-Control models, such as ICS or IMS, which are in use in communities.

Why Healthcare Settings Are Different

In the emergency planning practiced in many communities, hospitals are either viewed with a certain degree of mysteriousness, or in the same category as independent businesses operating in the community. In the first case, their roles and abilities as far as emergency management is concerned are mostly a matter of blind faith or sometimes erroneous assumptions. To illustrate, the community Emergency Plan simply states that, in the event that the passenger train which passes through town three times each day ever derails, “the injured will be taken to the hospital.” This generates an assumption which essentially ignores the fact that the local hospital probably doesn’t have either the capacity or the resources to handle all of those trauma patients,2 or may be a signatory to a regional hospital programme agreement, in which another hospital, miles away, is the designated receiving location for all trauma patients.

The primary business of every hospital is essentially clinical; everything in the facility can be related in some fashion, either directly or indirectly, to meeting the medical needs of the patients. Additionally, hospitals are arguably, along with long-term care facilities, the single greatest concentrations of truly vulnerable individuals within any community.3 That vulnerability arises, for the most part, as a direct result of the clinical condition of each patient, and of the medical treatments and procedures which they have received.

The degrees of vulnerability, and the support required, vary as a direct result of clinical situations. To illustrate, it is relatively easy to evacuate a voluntary mental health patient to another facility, whereas a general surgical patient requires more support, and a patient who is freshly post-operative or in the Intensive Care Unit, will require a tremendous amount of support to be safely evacuated. The other two factors which play a major role in influencing evacuation in a hospital are the relative degree of mobility (a MAJOR issue), and, in some cases, the degree of supervision required to ensure patient safety.4 In general terms, those conducting “mainstream” emergency management or response activities in the community rarely possess an appropriate level of understanding of the clinical issues which drive so many of a healthcare institution’s emergency decisions, or even how they operate on a day-to-day basis.

The second case, in which hospitals are essentially independent businesses operating in the community, is equally erroneous. Independent businesses have limited and specialized resource bases, and in a disaster, are likely to be primarily focused on their own survival. Hospitals are specialized, but have a broad resource base, and are focused on the survival of the community, with their own survival being an important secondary consideration.

Most healthcare facilities are truly communities in miniature, although a great deal more specialized in their core business and on a smaller scale. In the Emergency Support Function model, which is described in detail in Chapter 1, of the 15 Emergency Support Functions (ESF) incorporated into the model, only ESF #10 (and increasingly, hospitals are being forced to develop their own internal hazardous materials spill response and decontamination arrangements) and ESF #11 (Agriculture and Natural Resources) do not have analogs operating within the facility. Community police are replaced by hospital security, EMS by the hospital Cardiac Arrest Team, Public Works and Utilities by the Engineering Department, and so on.

Location-Specific Factors

While some locations enjoy a relatively free choice with respect to Command-and-Control model selection, others must meet specific mandates, often legislated. Such systems are generally attempting to ensure that all parties responding to an emergency are using a single, predesignated Command-and-Control model, ensuring coordination. Participation in such systems may be voluntary, but it may also be based on such government strategies as being able to demonstrate compliance in order to access preparedness funding grants. While such systems are both coordinated and interoperable across multiple types of organizations and service providers, they only rarely fully address the specific needs of each type of participating organization or agency from their Command-and-Control model.

In the United States, Federal legislation has mandated that no preparedness grant funding would be available to any agency unless it was fully compliant with the United States. National Incident Management System command and control model,5 and various sectors, including healthcare, were provided with actual deadlines for compliance. In the United Kingdom, the Gold, Silver, Bronze system has become the accepted standard for command and control, including the healthcare sector.6 In Australia, Federal legislation mandates the use of the AIIMS model.7 While such directions are well-intentioned, they are, of necessity, somewhat generic, and only rarely will a participating organization find that they can participate during a crisis without considerable advance consideration of “work-arounds” which will permit the organization to meet its own specific needs, while remaining in compliance.

Such directives may also force organizations with their own specific procedures, chains of command, language, and priorities to suddenly adopt a less familiar Command-and-Control structure during a crisis, with a corresponding degree of potential for confusion to result. The only alternative to this is the provision of fairly extensive and ongoing training initiatives, in order to ensure that staff become and remain familiar with an operating system which is different from that which is used on a day-to-day basis, and also to understand how many essential daily procedures may be changed by the presence of this new model.

Such training is generally accompanied by considerable additional training costs for the organization involved, and it may divert carefully budgeted staff to needed training initiatives, instead of providing necessary services for the patients who are in their care. It may be argued that in most societies, hospitals and healthcare organizations operate with limited budgets, and are often faced with competing priorities, most of which provide an immediate benefit to the patient population. The potential impacts of such mandatory additional training costs should, in all cases, be carefully considered by the relevant government agency, prior to imposition on the hospitals; they may have an immediate adverse effect on carefully budgeted patient care services which the government could not have foreseen. That is not to say that such organizations do not require command and control models which are compatible, only that this mandatory “one model fits all” approach may be, at best, misguided. Compatible, interoperable, and identical are not necessarily the same things.

With all of the above being said, it may well be that some degree of mandatory standardization has validity within specific sectors of the response. There is merit in ensuring that all of the police operate in the same way, or all of the fire departments, or all of the healthcare providers. In the UK, the frameworks for response, while standardized, are developed for specific sectors. The National Health Service does provide a mandatory framework for Emergency Preparedness, Response and Resiliency for all types of healthcare providers, which meet the needs of the healthcare system, but do not follow precisely the same model as the emergency services.8 The key to success with such an approach is to ensure that while the specific needs of both organizations and sectors are respected, the issue of creating points of integration between agencies is also addressed.

Healthcare-Specific Resources

The use of such Command-and-Control methodology is not new to healthcare, although it has not typically been specifically described as such in the past. The basic elements of a Command-and-Control model are much less “alien” to healthcare professionals than one might at first think. After all, hospitals and healthcare professionals might be argued to be in the crisis management business, and to deal with some level of crisis, albeit on a smaller scale, almost every day. This method of controlling actions and resources can actually be found in various places in the practice of modern medicine, if one simply looks closely enough. The extent to which such models have found their way into the healthcare setting is often somewhat driven by the degree of criticality of the situation being managed, and by the absolute need to eliminate errors from the activity which is occurring.

To illustrate, take a look at a typical operating theater. Everything revolves around the medical needs of a single, extremely vulnerable, patient, whose condition and safety are the paramount priorities. Now apply the basic ICS model to that setting. The lead surgeon is the Incident Commander, the assisting surgeon is the Operations Lead, the anaesthetist is the Safety Officer, the circulating nurse is the Logistics Lead, the scrub nurse is doing Short-Term Planning, the charge nurse for the OR is doing Long-Term Planning, and also some Liaison and Public Information, as required.

The principal objective is the safe resolution of the patient’s medical issues, and the lead surgeon has conducted the appropriate research, and has formulated a clear and concise plan for achieving this goal, set objectives and assigned work to the individuals on the team, all the while being fully supported by the team members. The patient will even be moved to the RECOVERY Room, in order to ensure that their condition returns to normal or “near-normal,” when the procedure is completed. When all goes according to plan, the patient’s situation is improved, and they return to their hospital bed, better for the work that the team has accomplished, and when things occasionally go wrong, the resources are already in place and organized to address that contingency effectively.

This type of scenario is not unfamiliar to front line staff, even if they have never heard the term “Command and Control model.” One can make similar arguments, differing primarily by scale, for the regular utilization of a Command-and-Control model by a trauma resuscitation team, a cardiac arrest team, or for managing the patient load in the Emergency Room or the Outpatient Department. Indeed, the model has some applicability in virtually every critical care setting in any hospital. It must always be remembered that during any crisis in a healthcare setting, front line staff, including physicians, nurses, and all other professional staff do what they always do; for them the differences in crisis response are not of scope, but of scale. It is the managers and the administration of the facility whose jobs and tasks will change, and who need to be able to do things differently.

On some levels, the roles within the Command-and-Control model of a healthcare system may be quite different from those of community agencies, even when the role labels are identical. To illustrate, in all cases, the Operations position is specialized, dealing primarily with the core business of the organization, whatever that core business might happen to be. As a single example of fundamental differences in roles, we shall compare and contrast the role of Safety Officer, within a fire department and a hospital setting.

In a fire department, the organizational role is likely to deal with fire suppression, rescue, and hazardous materials, while in a hospital, it will be about the throughput and care of patients; those generated by the emergency, and also those who were already present in the hospital when the emergency occurred. Similarly, the Safety role in a fire department is likely to be about personal protective equipment, exposure tracking and documentation, and procedural safety, but in a hospital, it may be about infection control and prevention, radiological protection, or the safe use of medical devices.

With a fire department Safety Officer, the role is likely to be primarily about personal protective equipment (for firefighters), fatigue monitoring, and oversight of decontamination procedures. In a hospital, while some of those things might take place on a limited basis, the issue of safety often deals with the impacts of medical procedures and devices, about which a fire department Safety Officer would have little or no understanding. When considered in the light of the ability of this role to stop procedures which they believe to be unsafe,9 this lack of familiarity could actually create unsafe situations, rather than resolving them.

Finally, while in communities many of those filling Key Roles in the Incident Management Team are likely to be frontline first responders and junior grade officers, pressed into service with specific instructions, those filling the same roles in hospitals are likely to be university-educated subject matter experts in their own right, with extensive experience working in a primarily clinical environment, and who must be credentialed in order to operate inside a healthcare facility,10 as a matter of both patient safety and hospital liability exposure. As a direct result of these realities, while there are many at various levels of governments and sectors of emergency management who advocate that such Key Role positions should be jointly operated or interchangeable between agencies, in the healthcare sector, this is simply not possible.

Hospital Incident Command System

Figure 2.1 Basic Hospital Incident Command System

History

The HICS Command-and-Control model has its origins in the Hospital Emergency Incident Command System,11 which was first introduced by the California Hospital Association in the late 1980s. The model was the first such attempt to introduce a specialized Command-and-Control model across a large sector, and the first such model in a healthcare setting. The model was felt to be necessary in order to make the then recently introduced ICS more applicable to hospitals and healthcare agencies, and to improve levels of coordination between hospitals and emergency services, which were using the ICS model. Now in its fourth version, the name has been shortened to the HICS, and its use has spread to hospitals and healthcare agencies across the United States and elsewhere. It is estimated that more than 6,000 hospitals and healthcare agencies are current users of HICS. The model is derived directly from the ICS model and can be fully integrated with it. It meets Joint Commission Accreditation Standards,12 and is also fully National Incident Management System compliant.13 Training in this model is available from a variety of sources, including online training programs offered by the California Hospital Association.14

Normal Operations

HICS, like all other ICS models, is intended to be both modular and scalable, in order to adequately address the specific needs of both the healthcare organization and the type and nature of the incident which is occurring.15 The size and structure of the model will also be driven, to some extent, by the size of the facility and the number of resources which are available for incident response. Under normal circumstances, an Incident Commander will be identified, who will then attempt to populate all of the Command and General Staff positions, in order of perceived priority and availability. Once this has occurred, any additional positions which are required are normally backfilled, as resources become available.

In the HICS model, there is tremendous reliance upon the population of all Command and General Staff roles by individuals who have received advance training, rather than short-term population with “ad-hoc” staff, and, as a result, the activation of the model may be slowed in some circumstances. Hospitals are large, complex entities, and the Command-and-Control model during a disaster can quickly escalate in size and complexity. The challenge may be to achieve the required size without affecting patient care services, or the ability to sustain a protracted operation of the model. In order to maintain reasonable spans of control, it may be that it will be necessary to “sector” key areas of service delivery under the various areas, such as sectoring the Emergency Department or the Operating Rooms, under Operations. Such sectoring may be based upon geographic considerations (e.g., hospital “wings or multiple operating sites”), or they may be based upon type of services being provided (e.g., surgery or “critical care areas”).

This model has been identified as a suitable Command-and-Control tool to manage hospitals not only during disaster responses but also for planned events. These could include planned utility interruptions, the planned movement of patient populations to new facilities, and labor disruptions. HICS can also be used to provide a framework for the preplanning of emergency responses.

Strengths

Because not all contingencies can be fully anticipated, particularly during a disaster, the model provides for planned improvisation in response to changing and evolving situations.16

The model maintains a relatively high degree of flexibility and fluidity, becoming larger or smaller as needed, and allows for the activation of only those roles that are actually required at any given time.

The model provides for an ability to maintain spans of control through the “sectoring” of service delivery, either geographically, or by service delivery sector.

The model is fully integrated and compliant with the National Incident Management System.17 This represents an advantage to American hospitals.

Weaknesses

When fully implemented, the model can be somewhat large and cumbersome. The exceeding of recommended spans of control may occur with some regularity (see Figure 10.1).

When fully implemented, many hospitals and healthcare agencies, particularly those smaller and more isolated rural agencies, would be challenged to find sufficient resources to populate all of the roles, without affecting service delivery.

The model places less emphasis on the use of “ad-hoc” staff, instead of predesignated staff that may not be immediately available, in order to achieve truly rapid activation.

Healthcare Emergency Command-and-Control System

Figure 2.2 Basic Healthcare Emergency Command-and-Control System Structure

History

The HECCS model was introduced in 2011 by the Ontario (Canada) Hospital Association, for recommended use in its 200 member hospitals. The organization had been providing training in the IMS to its member facilities since 2003, but it was felt that the mainstream IMS model was strong, and remained useful, but did not fully address the specific needs of a healthcare facility during a crisis.

Chief among its concerns was the concept of the interchangeability of key role staff, as it was felt that hospitals were too specialized and had too many liability issues to permit the filling of key roles by those from other organizations who lacked familiarity with either the environment or the operating issues. Further, there was a concern that there appeared to be an expectation that trained staff from the healthcare facility might be “borrowed” by the community at a time when they were actually needed in their own environment. In the United States, a similar set of concerns had led healthcare to the development of the HICS model.

It was felt that a healthcare-specific model was required. The HICS model was examined but was found to present its own specific concerns. The minimum staffing model generated a large enough demand for staffing that it presented potential problems for the local healthcare operating model, as it would actually require the removal of staff from patient care roles in many facilities, in order to simply staff all of the required positions. It was felt that, apart from a few large teaching facilities, this would be a problem.

It was also felt that with such a large number of participants operating in the Command-and-Control model, consultation and decision making could become cumbersome, and might actually lead to a slowing of the ability to arrive at decisions and react effectively to evolving situations during a crisis. Finally, there was a concern that all hospitals tend to be organized according to their own specific needs and experiences, and that the assignment of specific functions to specific key role positions might result in hospitals which adopted the model having to either completely re-structure their day-to-day operations, or to completely re-organize themselves to a largely unfamiliar reporting structure each time that a crisis occurred.

The model was designed with the specific requirements of hospitals and other healthcare facilities in mind, with a small, trained cadre of individuals in key role positions, enabling meetings to be short, and reactions to occur quickly, when required. It also created multiple layers of redundancy, with numerous individuals trained for each specific role. The model recognized the operational reality of hospitals, by ensuring that the model provided specific tools which permitted its activation and short-term operation by “ad-hoc” staff until the predesignated staff could arrive, outside of normal business hours.

The model also standardized the “key roles” of the upper tier of the IMS model, while recognizing that each hospital would assign responsibility and subordinate reporting to the key role staff, based upon its own individual day-to-day procedures and operating realities. The model was further strengthened by short course training, and a certification process for emergency managers wishing to work in a healthcare setting,18 which can be delivered on-site at individual hospitals, if required, and a comprehensive tool kit for implementation.

Under normal circumstances, the organization will operate under the direction of a predesignated Incident Manager, who is responsible for the analysis of events and situations and the assignment of work, and who has a direct reporting relationship with either the hospital CEO or with the Board of Trustees. All authority and responsibility for the response to whatever the emergency might happen to be is vested in the Incident Manager.

The Incident Manager may then delegate the authority (but not the responsibility) for specific, defined functions to predesignated individuals who will occupy the seven Key Roles on the organization chart (Figure 2.2). None of these positions is mandatory; they all exist at the pleasure of the Incident Manager, as and when they are actually required, and may be stood down, once they are no longer required. The Incident Manager is actually delegating elements of their own authority, in order to get work done.

The Incident Manager may, subject to guidelines, activate the Hospital Command Center, or some other appropriate Point of Command, as well as a Media Information Center, a Family Information Center, and a Staff Reporting/Staging Area, as facilities deemed to be potentially valuable to the operation of a healthcare facility, during any type of crisis. If the event is large enough that it cannot be managed with the immediately available resources, the Incident Manager is also authorized to activate any emergency staff recall procedures, such as fan-out lists. The Incident Manager may also order the activation of expanded triage/treatment spaces, or the evacuation of the facility, as required. The Incident Manager may also, in consultation with senior management, order the suspension of outpatient and other day services, and may, in consultation with the Chief of Staff, order the suspension of nonemergency surgery for the duration of the emergency.

Regular meetings of key role staff, called Business Cycle meetings, will occur in order to facilitate the exchange of information, status updates, progress reports, problems encountered, and the assignment of new tasks. The frequency and duration of the Business Cycle are flexible, based upon the needs of the incident, and are determined by the Incident Manager. All meetings are documented, in terms of an Event Log, and are reported through regular Situation Reports during the event, and After-Action Reports following the event. The event response will stand down, once the Incident Manager, in consultation with senior management, determines that it is safe and appropriate to return the facility to normal operations, with a plan for restoration of normal services being formulated and approved in advance. The HECCS Command-and-Control model is derived directly from the mainstream IMS model, and, as a result, can operate without complication with any other organization which is using the IMS or ICS model.

Special Functions

This model has been identified as a suitable Command-and-Control tool to manage hospitals not only during disaster responses but also for planned events. These could include planned utility interruptions, the planned movement of patient populations to new facilities, and labor disruptions. HECCS can also be used to provide a framework for the preplanning of emergency responses.

The model recognizes a need for at least one full-time Scribe, in order to support the Incident Manager with the documentation of decisions and actions. While other models sometimes recognize the potential need for such a position, this is the only model which mandates its development as a permanent feature, and the predesignation of specific staff to the role.

The model also recognizes the need for a cadre of support staff to provide services for those actually operating as the HECCS Team. The presence of such staff appears to be implicit in other models, but only in the HECCS model are specific roles and requirements preidentified.

The model recognizes that only very rarely will a hospital or other healthcare facility possess a dedicated, purpose-built Command Centre from which to operate during any emergency. In most cases, the Command Center will be a multiuse space, such as a Boardroom, incorporating the use of some type of equipment “kit” for its conversion to purpose. Moreover, the development of backup operating locations, in addition to the primary location, will be required in case the emergency event denies the use of the primary designated operating location. The HECCS model recognizes this through the use of case-specific Annexes and Job Action Sheets which are expressly created to meet this need.

Strengths

The HECCS model can be activated and implemented by inexperienced staff, using written, preapproved, and easy-to-follow guidelines called Job Action Sheets, which are found in the Annexes of each copy of the Emergency Response Plan in the facility. These provide clear, unequivocal “trigger points” for activation, thereby removing any uncertainty on the part of “ad-hoc” staff. There is a clear expectation that “ad-hoc” staff will be replaced by predesignated individuals, and their previous decisions and actions confirmed, as soon as the predesignated staff member arrives. As a result, even after hours, the model can be activated quickly; often with most of the activation steps completed and the management of the incident underway, prior to the arrival of the predesignated staff.

The model allows for the assignment of multiple roles to a single individual over the short term, either for relatively small incidents, or during the early stages of large incidents when resources are not immediately available. Specific roles are preidentified for short-term “pairing,” based upon a similarity of functions. To illustrate, the Public Information and Liaison functions are both primarily about the sharing of information, albeit with different groups. As a result, these two functions may be paired, over the short term, until resources become available. Similarly, the Incident Manager may simply decide to retain direct control of the Operations function, in addition to their regular duties, during a small incident, or when appropriate resources are not immediately available. Logistics is typically about various types of resources, which have monetary costs, and Finance deals with monetary costs, so short-term “pairing” of these functions may also be feasible.

The model provides specific resources which may be essential to a hospital or a healthcare facility, but largely unknown in other types of agencies. These include facilities for the triage of arriving patients, the decanting of a hospital in order to make room for new patients, the distribution or the re-distribution of disaster-related patients among multiple hospitals in order to balance workload distribution or to meet specific clinical needs. They also include the outright evacuation of the facility; a situation in which the hospital also needs to retain direct control over when, how, and to where, each patient will be evacuated, because of specific clinical requirements. Such issues are rarely considered in “mainstream” IMS and ICS models, which often have no expertise in the issues surrounding a healthcare facility, and they may not even permit “deviation” from what they regard as a “standardized” model or framework for response.

The model is sufficiently flexible to permit its application to all manner of abnormal events. This can often reduce staff training costs associated with the model, as using the model, specifically the case-specific Annexes and Job Action Sheets, for smaller emergencies such as a single missing patient, means that staff will very likely have already been exposed to the model when a large event, such as a mass-casualty incident occurs. This results in a “change in culture” for the organization, in which the HECCS model is not something unfamiliar which is introduced only during a major crisis, but rather, quickly becomes “the way that we manage every abnormal event in this hospital.”

Another strength of the HECCS model is its ability to act not only as a response framework, but also as an advance planning framework for the facility. It is perfectly appropriate to break down the advance planning and procedural development associated with the Emergency Response Plan into those key issues which every organization must at least consider during a crisis. As a result, the development of Emergency Preparedness subcommittees focused on each of the seven key roles provides an appropriate planning framework. By staffing the subcommittees with those with primary and secondary responsibilities for predesignated roles, the work becomes directly relevant, and the plans and procedures are created by those who are most likely to have to implement them during a real event.

Weaknesses

The most fundamental weakness in this model is that shared with virtually every Command-and-Control model. In order to be effective, and to be remembered by staff, it must be practiced regularly. This means a need for regular training updates and exercise practice, particularly for predesignated staff. If an event occurs on a regular basis, this focus on exercises may not be required, but will remain necessary for all types of events which have not occurred, if for no other reason than as a “refresher.” While the case-specific Annexes and Job Action Sheets will suffice for “ad-hoc” staff over the short term, they are intended as a stopgap measure, to be used only until such time as the designated staff arrives.

Formalizing Supporting Roles

Figure 2.3 HECCS supporting roles

One of the most commonly overlooked strengths of the Command-and-Control models used in the healthcare sector is the ability to tap specialized resources which are generally already operating within the facility. While the generic and mainstream models may require individuals in support roles, they will often have to source such individuals and obtain their use, or appoint individuals to provide these functions, whether or not they are a part of their day-to-day duties, on an “ad-hoc” basis. In doing so, it may be necessary to take these individuals away from other needed functions. To illustrate, during a crisis, is a uniformed policeman more valuable on the street, or providing security at the entrance to the municipal Emergency Operations Center?

Fortunately, in the healthcare setting, there is a need for such resources on a daily basis. Almost all hospitals already have security guards, housekeeping staff, engineering staff, dietary staff, clerical staff, and so on. Indeed, it can be argued that, with the possible exception of the smallest hospitals, every type of service which is available in the community at large has an analog operating inside the hospital, albeit on a smaller scale. Knowing that such individuals are available on a continual basis within the hospital allows the Emergency Manager to secure the services of these individuals in advance, and actually formally incorporate their roles into both the Command-and-Control model and the Emergency Plan itself.

Choosing a Model

While compliance with legislated mandates and standards is both necessary and desirable, the choice of Command-and-Control model should, in the opinion of the author, remain the prerogative of each healthcare agency. The first priority of any Command-and-Control model should be the effective response of the organization to whatever crisis or disaster is occurring. Organizations, when left to their own devices, typically choose a model which best meets the specific needs and realities of their own organization and its core business. In many cases, imposed Command-and-Control models tend to improve interagency coordination at the direct expense of meeting, or in some cases, even recognizing those needs, within each participating organization. In those circumstances in which the Emergency Manager has the latitude to do so, any choice of a Command-and-Control model for a hospital or a healthcare agency should be made with a priority placed on meeting the specific needs of the organization, with interagency coordination being viewed as a highly desirable secondary consideration.

Interoperability

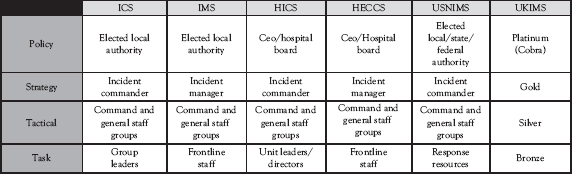

Figure 2.4 Command-and-Control system interoperability

Despite the differences of many of the Command-and-Control systems, both specialized and generic, which are in current use, integration and interoperability is both feasible and relatively easy to accomplish. Despite the differences in titles, the fundamental reporting relationships, and, in most cases, the basic labels of each model are relatively identical (see Figure 2.4). Safety remains Safety, Planning remains Planning, and so on. Typically, effective coordination of the resources of multiple agencies may be achieved using one of four approaches.

The first approach to coordination is the co-location or conferencing of those at the Strategy level (Incident Commanders, Incident Managers, Incident Controllers, and Gold Command). This is the normal method of major incident coordination in the British Gold, Silver, Bronze model. It is also not uncommon among the command officers of the various emergency services while operating at the site of a major incident. In the case of emergency services, they may elect to choose a single commander, they may agree to a joint command operation, or they may transfer command among themselves, based upon the specific major expertise and resource requirements of each discreet stage of the incident response.

The second approach to coordination is the creation of interagency Task Forces, as is practiced in both the generic ICS and the U.S. National Incident Management System models. In such cases, the Task level resources of two or more agencies may be placed under the authority of a single individual, and they may be assigned to perform specific functions. A Heavy Urban Search and Rescue team is an excellent example of such a resource, with police officers providing security and searching for survivors, firefighters providing access and extrication for victims, heavy equipment operators supporting firefighters in the rescue function, and paramedics providing medical care to victims both during and following extrication. Most examples of such Task Forces, however, occur on an “ad-hoc” basis, and are usually intended and tailored to meet the specific needs of each incident.

In the third approach, the local authority, usually an elected Council, will name a specific individual, often the Fire Chief or the Police Chief, to lead the emergency response resources through any major crisis or incident response. This is most common in small communities in which all of the response resources belong to that actual community and are not going to be operated by other levels of government or private providers. This model is most effective when the arrangements are agreed upon well in advance, and the participating agencies have the opportunity to train and work together, and when they have developed a “trust” of one another.

One of the challenges is that, not unlike some of the Command-and-Control models already discussed, the appointment of a single individual from one particular agency may mean that the person in charge does not have a truly comprehensive understanding of the knowledge, skills, resources, or capabilities of all of the agencies which he or she is supervising. With the advent of more formal Command-and-Control models, this particular approach to multiagency coordination is slowly disappearing from common usage.

The fourth approach utilizes the elements of the Tactical level of the various Command-and-Control models. It takes the position that those at the Strategy level are essentially too busy appropriately evaluating information and assessing and directing their own response to become a point of coordination. As a result, those at the Tactical level become highly effective points of coordination across multiple agencies. This occurs through each of the actual role labels, with Logistics teaming with Logistics from other agencies, Public Information doing the same, and so on.

The result is very similar to the Task Forces employed in both the generic ICS model, and in the US National Incident Management System model. The important difference is that in this approach, the Task Forces will be role-specific, instead of task-specific. In this manner, it is entirely possible for independent Logistics operations from each agency to support one another, for all of the Public Information people from the various agencies to come together and formulate a single, comprehensive media plan and consistent associated messaging, and so on. Such an approach, while highly effective and highly desirable, requires both training and regular practice.

Student Projects

Student Project #1

Examine the HICS Command-and-Control model in detail. Select a single, simple, disaster scenario, and describe how the hospital under study would have its response efforts integrated with those of the emergency services located in the community served by the hospital, using the National Incident Management System. Identify three strengths to this approach, and also three weaknesses to the approach, proposing solutions for the weaknesses identified. Construct a logical argument either for or against this approach to integration, defending your positions appropriately. Ensure that all information is suitably and appropriately cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Student Project #2

Examine the HECCS Command-and-Control model in detail. Select a single, simple, disaster scenario, and describe how the hospital under study would have its response efforts integrated with those of the emergency services located in the community served by the hospital, using the National Incident Management System. Identify three strengths to this approach, and also three weaknesses to the approach, proposing solutions for the weaknesses identified. Construct a logical argument either for or against this approach to integration, defending your positions appropriately. Ensure that all information is suitably and appropriately cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully and select the MOST CORRECT answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (eight correct answers), you should re-read this chapter.

1. Specialized Command-and-Control models may be required in a healthcare setting because mainstream models often:

(a) Fail to address important clinical realities

(b) Use interchangeable staff in Key Roles

(c) Can impose additional training costs

(d) All of the above

2. The HICS has its origins in the:

(a) Gold, Silver, Bronze System

(b) Incident Command System

(c) U.S. National Incident Management System

(d) Australian AIIMS System

3. In the Healthcare Emergency Command-and-Control System, those roles which are immediately subordinate to the Incident Manager are called:

(a) Command Staff

(b) General Staff

(c) Key Roles

(d) Supporting Roles

4. In generic Command-and-Control models, it may be possible to use trained staff interchangeably between organizations. This practice is impossible in healthcare settings, because:

(a) Healthcare settings are too specialized

(b) It is illegal to do so

(c) Healthcare staff are more difficult to manage

(d) The roles are completely different

5. One of the most significant strengths of the HECCS model, is:

(a) Everyone in healthcare already understands it

(b) The ability to use ad-hoc staff to activate the model over the short term

(c) The ability to communicate quickly with the hospital’s trustees

(d) All of the above

6. In the United States, any healthcare based Command-and-Control model is required by law to be:

(a) Compliant with accreditation standards

(b) Compliant with international standards

(c) Compliant with the U.S. National Incident Management System model

(d) All of the above

7. One of the greatest challenges with complete interagency standardization to a single Command-and-Control models is that such practices typically achieve standardization at the expense of:

(a) Agency-specific needs

(b) Agency-specific preferences

(c) Previous training

(d) Both (a) and (b)

8. Healthcare-specific Command-and-Control models are able to fully integrate with most other Command-and-Control models by creating formal points of coordination at the:

(a) Strategy level

(b) Tactical level

(c) Task level

(d) Policy level

9. A significant strength of both of the healthcare Command-and-Control models discussed, is that in addition to managing disaster/ crisis response, it is also possible to use them for:

(a) Managing scheduled events

(b) Managing special events

(c) Creating a planning framework

(d) All of the above

10. By linking together similar positions across the Command-and-Control models of all agencies responding to a disaster/crisis, it becomes possible to:

(a) Create role-specific Task Forces

(b) Provide joint work direction

(c) Source unusual items

(d) All of the above

Answers

1. (d) 2. (b) 3. (c) 4. (a) 5. (b)

6. (c) 7. (a) 8. (b) 9. (d) 10. (a)

Additional Reading

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics covered in this chapter:

CHA. 2014. ICS/NIMS Online Training Course, California Hospital Association website, www.calhospitalprepare.org/icsnims-online-course (accessed February 25, 2014).

ICS Canada. 2012. Incident Command System Operational Description, ICS Canada, .pdf document, www.icscanada.ca/images/upload/ICS%20OPS%20Description2012.pdf (accessed February 28, 2014).

IS-100.HCB: Introduction to the Incident Command System (ICS 100) for Healthcare/Hospitals, Independent Study Course, http://training.fema.gov/EMIWeb/IS/courseOverview.aspx?code=IS-100.HCb (accessed March 01, 2014).

National Health Service. 2013. Core Standards for Emergency Preparedness, Response and Resiliency, NHS Commissioning Board, London, www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/eprr-core-standards.pdf (accessed February 28, 2014).

OHA. 2009. Emergency Management Toolkit: Developing a Sustainable Emergency Management Program for Hospitals, Ontario Hospital Association, Toronto.