Key Roles in Command-and-Control for Healthcare

Introduction

No Command-and-Control model can function without people. The organization table and the reporting structures only work effectively when they are occupied. Hospitals and healthcare agencies are somewhat unique, in that many, or indeed, most, already possess residential expertise in most of the areas of knowledge and skill sets which are required to guide the facility through any incident. It is often a matter of identifying that expertise and pressing it into service.

This chapter will examine those roles which are the specific requirements of a healthcare-based Command-and-Control model. The duties, the reporting structures, and the potential subordinate staffing arrangements for each will be examined in detail, along with methods of using these roles as highly effective points of coordination/collaboration between the healthcare organization and outside agencies, including those in the community. In each case, we will attempt to identify suitable candidates in terms of both knowledge and expertise, for each role, from within the staff pool which is normally found in most hospitals. We will also examine the short-term usage of “ad-hoc” staff in each position, along with the requirements for doing so.

This chapter will also examine the supporting staff requirements which may be anticipated. These include roles which are central to the success of the Command-and-Control model, such as the Scribe. It will also examine those support services which are required in order to permit the Incident Management Team to function in an environment which is conducive to success, and which is as seamless as it is possible to make it. In each case, we will attempt to identify the potential sources of such personnel, and how to obtain their use. It should also be noted that, while work areas are organized under specific Key Roles in this chapter, these are merely suggestions. Every hospital and healthcare facility already has an organizational reporting structure, which is based upon local need and local realities. The intent here is to standardize the Strategy and Tactical levels; the Task level remains, organizationally, a matter of local autonomy. None of the subordinates listed are mandatory, they are simply suggestions.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the student should be able to clearly describe each of the Key Roles for a healthcare-based Command-and-Control system, along with their responsibilities, appropriate selection criteria, and reporting relationships. The student should also be able to describe appropriate supporting positions for each of the Key Roles, as well as those positions which, while not an official feature of the Command-and-Control model, are nevertheless essential to its success. Finally, the student will be able to describe those support resources which are required in order to make the functioning of the Incident Management Team as smooth and “seamless” as possible.

Incident Manager

Every incident is best resolved when a single person assumes both responsibility and control of the response efforts. The title of this individual will vary, according to the Command-and-Control model which is in use, but the role and duties remain essentially unchanged. They may be known as the Incident Commander (USNIMS,1 Incident Command System [ICS], Hospital Incident Command System [HICS]), the Incident Manager (Incident Management System,2 Healthcare Emergency Command and Control System [HECCS]), the Incident Controller (Australasian Inter-Service Incident Management System3), or the Gold Commander (UKNIMS). Regardless of the title, this is the leadership role for all Command-and-Control models and is the organization’s principal strategist for the response to the event.

The Incident Manager holds both the authority and the responsibility for the resolution of the incident. While authority for a given portfolio of duties may be delegated to a subordinate, the responsibility always remains with the Incident Manager. The Incident Manager is responsible for determining which of the other Incident Management Team Key Roles are required, and for the appointment of individuals to fill these roles. All of the Key Roles exist in order to lighten the burden of the Incident Manager through the delegation of workload, in order to permit the Incident Manager to focus more exclusively on the actual high-level management of the incident. No role, other than the Incident Manager, is automatically created; all roles exist as and when the Incident Manager determines that they are required and may be terminated when the Incident Manager decides that they are no longer needed.

The Incident Manager is responsible for the creation of a formal or improvised Incident Action Plan,4 the setting of goals and objectives and their assignment as individual tasks and duties, and for monitoring these for both progress and completion. The purpose of such a plan is to guide the organization through the crisis, to its successful resolution. The Incident Manager is, in essence, a Project Manager, and the Incident Action Plan may be quite correctly viewed as a formal Project Plan. If created correctly, it will include essential and nonessential but desirable tasks, an order of completion, milestones, and timelines for completion, complete with a critical path. As a result, good project management training and the associated skills are highly desirable in an Incident Manager.

The Incident Manager will conduct an initial briefing for all Key Role staff and will set a schedule for the group’s Business Cycle meetings. The timing and duration of such meetings will be periodically adjusted by the Incident Manager, in order to meet the needs of the organization and the demands of the incident. The Incident Manager will also meet with those at the Policy level of the organization, in order to ensure that they are adequately briefed regarding the nature of the incident and its impacts on the organization. The Incident Manager is also responsible for all of the documentation associated with the incident, including the Incident Log, the Incident Action Plan,5 Situation Reports (Sitreps),6 Post-Event Debriefing Reports, and After-Action Reports.7

Those filling the role of Incident Manager should be predesignated within any healthcare organization. There should always be a number of predesignated individuals which is sufficient to provide the depth to rotate on-call assignments and to facilitate both 24-hour scheduling and protracted operations. Suitable candidates are those with exceptional leadership and project planning skills, a detailed knowledge of the organization and how it functions, and sufficient position authority to direct work effectively. This may be viewed as a developmental opportunity for those seeking greater responsibilities within the organization.

That being said, the operational realities of most healthcare organizations are such that almost anyone in a healthcare setting may be called upon at some point to become an “ad-hoc” Incident Manager; in small events, such as a single missing patient, it will probably fall to the Charge Nurse of the affected Unit by default. It is also possible, particularly outside of normal business hours, that an “ad-hoc” Incident Manager may need to establish control of an event, and to direct the response until such time as a designated Incident Manager can arrive to relieve them. In such cases, the organization will benefit from a clear, concise, well-written Emergency Response Plan, along with additional tools, such as Job Action Sheets, intended to support the activities and the decisions of “ad-hoc” staff until such time as the predesignated staff arrives.

The Command Group

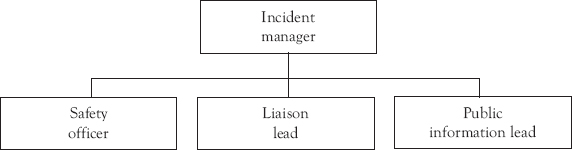

Figure 3.1 The Command Group—Basic structure

The subgroup of the Incident Management Team Key Roles, sometimes referred to as the Command Group, reports directly to the Incident Manager. It consists of three roles which are specifically intended to lighten the workload of the Incident Manager, by the delegation of specific tasks to individuals and teams who are, for the most part, specialists. Each of these fulfills a role which is either a legislated mandate, a potential liability exposure, or an otherwise legitimate expectation of the person in charge. Each of these roles is a feature of almost every widely used Command-and-Control model. There are three such roles, the Safety Officer, the Public Information Lead, and the Liaison Lead. Each of these will be examined and discussed individually, in the context of use in a hospital/healthcare organization.

Safety Officer

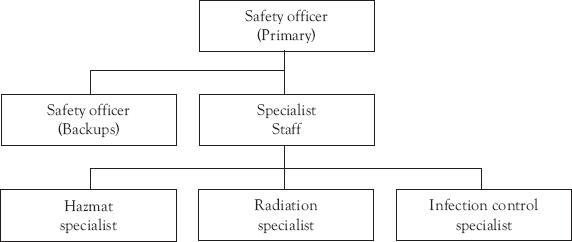

Figure 3.2 The Safety Officer Group with subordinates

The role of the Safety Officer in a hospital/healthcare setting is to take whatever measures are possible to ensure the personal safety of all of those who may be present within the facility. This includes patients, visitors, staff members, contractors, and anyone else who happens to be physically present in the facility while the incident is ongoing. This position is responsible for the ongoing monitoring of activities, work and other procedures taking place in the facility, in order to ensure safety. In most systems, the Safety Officer will be vested with the authority to order the immediate stoppage of any work or activity which they believe to be unsafe for the participants, or to represent an immediate threat to the safety of others.8 The Safety Officer is also responsible for the ongoing review of procedures and equipment, in order to identify any potential issues related to safety. The provision of recommendations to the Incident Manager regarding changes to emergency or routine procedures and protective devices, including personal protective equipment are also within the purview of this role.

In many jurisdictions, the Incident Manager, as the “most responsible person” would be directly liable for the safety of others. Clearly, during an incident, the typical Incident Manager has too many other immediate and pressing responsibilities to devote the time and attention to the issue of safety which it deserves. As a result, they delegate this responsibility downward, preferably to a predesignated individual who possesses an appropriate background, training, and knowledge base, to provide the issue of safety with the attention which it deserves. While the use of predesignated staff is ideal, and should be used wherever possible, the operational realities of a hospital are such that the position may need to be filled over the short term, particularly outside of normal business hours, through the use of “ad-hoc” staff. With this in mind, such individuals should be supported, through the use of clear, concise, advance directions, including both the Emergency Response Plan, case-specific Annexes, and Job Action Sheets, to ensure that they can function appropriately in the position, until relieved by predesignated staff.

Selection

The role of Safety Officer is often predesignated; usually to one who fulfills a similar role on a daily basis. As an alternative, or to create depth within the position, it may also be possible to predesignate members of the organization’s health and safety committee, preferably those with the longest service and highest level of training. In some jurisdictions, governments have created certification processes which ensure the competence of committee members, and such certified members are an ideal resource to expand the depth of the Safety Officer position. This role is also unique, in that the position of Safety Officer may also be staffed on the basis of specific areas of expertise, which may be determined by the nature of the actual incident.9 To illustrate, it may be appropriate to use a Radiologist or even a technician as Safety Officer in the case of a radiation spill, or a Chemist from the hospital laboratory, in the event of a hazardous materials spill.

Interagency Integration

Figure 3.3 The interagency safety task force (one example)

Within the emergency services, it is not uncommon for the role of safety to fall to an inter-agency team. In the ICS, this is called a “Task Force.” Essentially, each of the agency Safety Officers bring their own subject matter expertise and knowledge to the team, and they operate as a functional unit. Once the Safety vests or tabards are in place, the color of the uniform under it becomes irrelevant; any Safety Officer will review any work occurring on the site, and order the work stopped, if they believe it to be unsafe. If an interagency dispute occurs, the Safety Officer from the appropriate agency will be summoned and will issue a final ruling.

Public Information Lead

Figure 3.4 The Public Information Lead Group with subordinates

During almost any major incident, the presence of members of the media poses a significant challenge. Managed correctly, the media can be a useful tool for the Incident Management Team. Handled incorrectly, or not handled at all, their presence and activities may pose a serious problem. The first thing to remember is that the members of the media are simply doing a job; they are attempting to inform the public issues and events which they believe will be of interest. How they accomplish this is largely up to the organization, and the presence of someone with experience at dealing with the media can make an incredible difference. This is the role of the Public Information Lead.10

The Public Information Lead is responsible for the creation of a formal Media Plan, which operates as an Annex of the Emergency Response Plan and the Incident Action Plan. The role of such a plan is to attempt to manage the presence of the media on hospital premises, and to ensure that the correct messaging goes out to the media, and from there, to the general public. They are also responsible for the protection of confidential patient information, and for ensuring that each patient’s right to privacy is not violated during their treatment in the facility. The Public Information Lead should be responsible for the operation of the hospital’s Media Information Center, with the support of a number of subordinate staff. They will also be responsible for the creation of Media Releases (with prior approval of the Incident Manager), arranging media conferences, interviews, and, where appropriate, tours and photo opportunities.

The Public Information Lead is also responsible for the advance creation of supporting information for the media, such as background information handouts, and biographies of key players. This information (often called “boiler plate” by the media) should be created and approved in advance, for immediate release when necessary. In summary, the job of the Public Information Lead is to ensure that the members of the media receive information, which is accurate, appropriate, and consistent, and to ensure that the message being received is the correct one.

Selection

Almost every hospital or healthcare agency has either an individual on staff or retains the services of a consultant, who is responsible for dealing with the media on a daily basis. During a crisis, those which do not have such a person are likely to quickly discover that one is required. This individual is the logical person to perform this role during any crisis. In some cases, particularly with smaller hospitals which lack media staff, it may be necessary to negotiate a shared service arrangement between the hospital which has such a resource, and those who might require it occasionally. In either case, the candidate selected should be consulted regarding both the assignment of supporting staff and resource requirements, and those requirements should be incorporated into the Emergency Response Plan.

Interagency Integration

Figure 3.5 Interagency public information task force (one example)

When a group of agencies are employing similar command and control systems, it is likely that each agency will have its own Public Information Lead, or someone with a similar title and responsibilities. Each of these individuals will have access to their own sources of information, often directly relevant to their own agency’s operations, and their own goals and objectives regarding the information which is to be released. That being said, there is little valid reason why the Public Information Leads from all agencies involved should not collaborate in a joint media operation, such as what might be described as a Public Information Task Force, in the ICS model. All of the Public Information Leads from all of the agencies have a closed meeting, come to an agreement, and from that point forward, a single, consistent set of information and messaging is provided to the media and the public, regardless of which source it is coming from. Agencies may deal with specific items individually, but the overall messaging remains consistent.

Liaison Lead

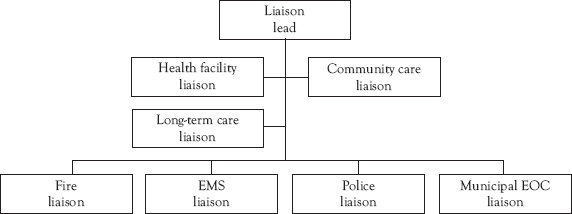

Figure 3.6 The Liaison Lead Group with subordinates

Every major incident is generally managed as a series of meetings. Some of these meetings are internal, such as the Business Cycle meetings, while others involve the interagency sharing of current information, problems encountered, and status. That being said, if the Incident Manager were to personally attend every meeting related to an incident, they would be left with little time in which to actually manage that incident! As a result, an ambassador of sorts is required. The role of the Liaison Lead is information sharing; in this case, to share with other responding agencies and levels of government,11 as opposed to with the media and the general public. The role of the Liaison Lead is to attend all external meetings and telephone/video conferences on behalf of the Incident Manager, in order to share their own information with outside agencies, and to collect appropriate information from those agencies to bring back to the Incident Manager. They will, in effect, become the “face” of the hospital or healthcare agency, to the balance of the response agencies.

The “currency” of disaster management is information. Every Incident Manager requires the best possible information upon which to base the required decisions for the management of whatever crisis happens to be occurring. It is for this reason that in most Command-and-Control models, the position of Incident Manager is in fact a “nexus” of sorts for the flow of information. That being said, the flow of information can, at times, become incredibly high, and not all of it is actually required by the Incident Manager. For this reason, the Liaison Lead must function as not only an information conduit but also as a filter; allowing through the relevant information and editing the “minutia,” so that the Incident Manager does not become overwhelmed by an unfiltered flow of unnecessary information.

Selection

The individuals chosen for the Liaison Lead role must be both diplomats and skilled communicators. They must also be sufficiently senior to ensure that other agencies do not perceive that they have been left to deal with a “minor functionary.” A relatively senior member of the hospital’s management team is often a good choice for this role. The Emergency Manager may be another good option; after all, it is rare that the Emergency Manager will be expected to actually run the incident.

Discretion is also essential; knowing how to ignore the sometimes “intense” atmosphere which occurs when individuals are under stress, and also knowing how to determine which elements of their own information should be released, and which should not. The Liaison Lead must also be a good judge of information and also reliable and trusted editor; ideally, someone who can be trusted to listen to the entire content of a 30-minute meeting, pull out the two major issues which are relevant, and return only those two issues to the Incident Manager. While one individual may be in charge of this function, it may also be possible to identify individuals who have extensive regular dealings with outside agencies and are known to them and trusted. There is no valid reason not to exploit such prior relationships; assuming that the individuals involved can be spared from their normal duties, and that such activities are centrally coordinated. It should be anticipated that this role may need to be filled over the short term by “ad-hoc” staff, until such time as predesignated staff can arrive. This reality should be supported by appropriate provisions in the Emergency Response Plan and the presence of appropriate Job Action Sheets.

Figure 3.7 The interagency liaison task force (one example)

As has already been stated, the Incident Managers are almost never in a position to attend such meetings, due to conflicting demands on their time. The one exception to this is the UKNIMS model, in which the vast majority of information sharing, and coordination occurs through the Gold Commanders. There is no valid reason why the Liaison Leads from all agencies involved in the incident response should not schedule regular meetings, either face to face or as teleconferences, in order to provide a regular, consistent program of information sharing, so that each agency is operating based upon the best possible information from all available sources. Such meetings may be scheduled around the Business Cycle meetings of the various agencies, usually following such meetings, in order to ensure that the information being shared is absolutely current.

The General Staff

The General Staff group reports directly to the Incident Manager. Its function is to conduct the actual response to the incident, as well as the “core businesses” of the organization, whatever that “core business” happens to be. In the case of a hospital or a healthcare agency, this group is involved in ensuring the operation of the throughput and care of patients, and the provision of patient care-related services. The dominant role in this group is the Operations Chief, who is primarily tasked with the conduct of core business; all other roles are intended to primarily support that role, or to respond to its activities. This group, along with the Command Staff, is considered a part of the “Tactical” level in most Command-and-Control models. All of these groups have a dynamic working relationship with one another, and their collaboration is directed at supporting Operations through the process of resolving the incident. In the simplest terms, this group may be characterized as the “thinkers” (Planning), the “do-ers” (Operations), the “finders” (Logistics), and the “payers” (Finance).

Figure 3.8 The General Staff

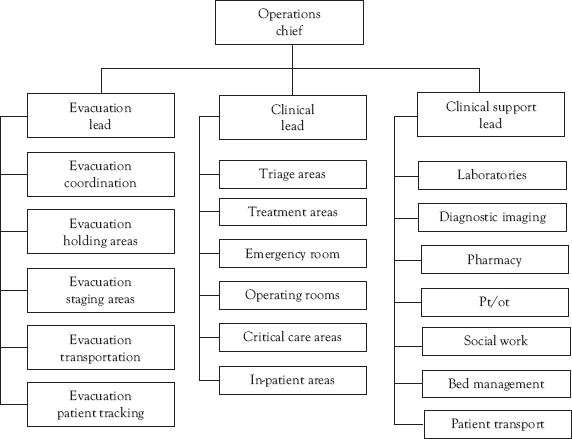

Operations is the second most important role in the most Command-and-Control models. The Operations Chief is the individual who is responsible for the core business of the organization, whatever that core business happens to be. In the case of a hospital or a healthcare organization, the Operations Chief is responsible for the throughput and care of all patients, whether generated by the incident being responded to, or already in the facility when the incident occurred.12 The position is also responsible for the physical egress and removal of patients, during any evacuation scenario. This role will be instrumental in all decisions regarding patient care-related resources, including the suspension or termination of regular services, such as outpatient clinics or elective surgery. The role reports directly to the Incident Manager. All other roles in the General Staff group primarily support this position.

Figure 3.9 The Operations Chief with subordinate roles

This role will also be responsible for the activation and operation of incident-specific treatment facilities, including triage areas, emergency treatment areas, patient holding areas, and so on. In addition to all of this, they will also ensure that all pre-existing in-patients continue to receive the care, treatment, and other services which they require. The Operations Chief’s subordinates include all of those groups and services which are primarily responsible for the provision of clinical care (physician group, nursing group, operating theaters, etc.) as well as a separate line of authority which covers clinical support services (diagnostic imaging, laboratories, blood bank, medical records, etc.). In summary, this role is responsible for the provision of all services which make a hospital a hospital.

Selection

The candidates for this position should possess, above all, a strong clinical background. They should have significant experience in the hospital, and exceptional leadership skills. They must possess detailed knowledge of the facility, the services and resources available, and how things work within the facility. The most logical candidates would be very senior members of the nursing administration or the physician staff, although in many hospitals, physicians are contractors, as opposed to actual employees, and may be reluctant to accept such a role. The candidates for this role should be predesignated, with both a primary candidate and sufficient backups to ensure adequate depth of coverage for around the clock or protracted operations. It should also be recognized that this role may need to be filled over the short term by “ad-hoc” staff, probably a more senior staff nurse, until such time as the predesignated Operations Chief arrives at the facility. As a result, adequate supports will need to be present in the Emergency Response Plan, such as clear, concise, case-specific instructions for various types of events in the Annexes, and suitable Job Action Sheets.

Interagency Cooperation

This position, like that of Incident Manager, is likely to be far too busy, and is far too specialized, to provide much opportunity for interagency cooperation.

Planning Chief

Figure 3.10 The Planning Chief with subordinate roles

The “conceptual thinker” of the organization. This individual is responsible for research, situational and resource analysis, and the identification and recommendation of both short-term (<eight hours) and long-term (eight hours+) strategies and actual plans.13 The duties are many and varied; they might include everything from the identification of the characteristics of the chemical that is leaking from a tanker outside the hospital, to critical care bed availability in other hospitals across the region. The Planning Chief is also normally responsible for the development of a Recovery Plan,14 which will provide for the planned and systematic transition from “disaster” mode back to normal operations. They are also generally responsible for assisting the Incident Manager in the creation and maintenance of a formal Incident Action Plan. Subordinates typically include those with responsibility for short-term planning, long-term planning, research, situational analysis, and resource analysis. In normal circumstances, the long-term planning role eventually transitions into the recovery planning role.

Selection

The candidates for this position should possess exceptional research and project management skills. The ability to apply analytical techniques, such as Root Cause Analysis15 and Value-Stream Mapping16 are also useful skills, as are familiarity and comfort with research tools, such as Internet search engines, Medline, hazardous materials databases, and so on. The candidates for this role should be predesignated, with both a primary candidate and sufficient backups to ensure adequate depth of coverage for around the clock or protracted operations. In many cases, the primary position may fall to the organization’s Emergency Manager. It should also be recognized that this role may need to be filled over the short term by “ad-hoc” staff, until such time as the predesignated Planning Chief arrives at the facility. As a result, adequate supports will need to be present in the Emergency Response Plan, such as clear, concise, case-specific instructions for various types of events in the Annexes, and suitable Job Action Sheets.

Interagency Cooperation

Figure 3.11 The interagency planning task force (one example)

The “currency” of disaster management and response is information, and the Planning Chiefs of each organization are its “information miners.” Since any Incident Manager requires access to the best information possible in order to make decisions, it is only logical that the Planning Chiefs of all participating organizations should meet on a regular basis, either in person or by teleconference, as a Planning Task Force. This will ensure the exchange of information from all sources and can facilitate the more detailed coordination of actual plans between the agencies.

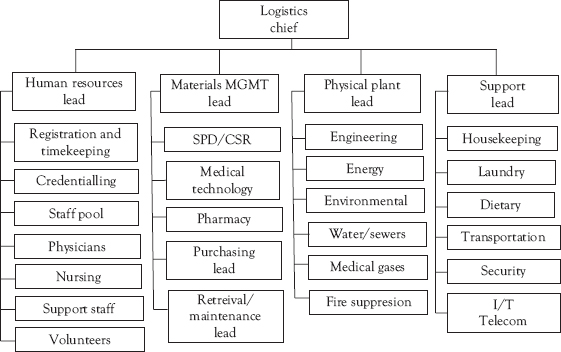

Logistics Chief

Figure 3.12 The Logistics Chief with subordinate roles

The Logistics role is primarily about providing those resources which are required in order to successfully manage the incident in question.17 Some of those resources are material, and others are people. In many cases, the identification of specific needs may actually be collaborative, with either Operations making a specific request or Planning identifying a specific resource shortfall. Logistics deals with the sourcing, acquisition, processing, delivery, and recovery of those resources, in support of incident operations. In most hospitals and healthcare facilities, it is normally a joint operation by Materials Management and Human Resources, either jointly or with one group, normally Materials Management, assuming the leadership role.

Many healthcare facilities also organize responsibility for physical plant operations and normal support services, including security, housekeeping, dietary, and transportation under this group. This arrangement can be particularly useful in a hospital, with the potential for the creation of task-specific multigroup Task Forces, such as for the discharge of patients and the reprocessing of those beds in order to make them available to new victims who require them. To illustrate, a team consisting of the Charge Nurse, a physician, and a Discharge Planner evaluate a patient and determine that they may receive either a discharge or a transfer to an alternate venue of care. The physician writes the discharge orders. The actual discharge, along with required support services and transportation, is arranged by the Discharge Planner. Patient Transportation moves the patient to a designated Holding Area within the hospital to await transport. As the patient leaves the bed, Housekeeping cleans the room and the bed, and adds new bedding. All equipment and inventory in the room is re-stocked and a safety inspection occurs. Admitting is notified that the bed is available for the next patient who requires it, and the bed reprocessing Task Force moves on to clear and reprocess the next available bed.

Selection

The appropriate candidates for this position will have a detailed knowledge of the hospital and of how it works. They will also have an extensive knowledge of hospital purchasing procedures and supply chains for all types of resources. They will also require extensive knowledge of human resources practices and procedures. While either Materials Management or Human Resources may be able to perform this role, it is likely that the “lion’s share” of the work will fall within the Materials Management sphere of influence. That being said, there is no reason why the primary should not be from Materials Management, with at least one designated backup from Human Resources. Each will need to learn the basics of the other’s field, in any case. The candidates for this role should be predesignated, with both a primary candidate and sufficient backups to ensure adequate depth of coverage for around the clock or protracted operations. It should also be recognized that this role may need to be filled over the short term by “ad-hoc” staff, until such time as the predesignated Logistics Chief arrives at the facility. As a result, adequate supports will need to be present in the Emergency Response Plan, such as clear, concise, case-specific instructions for various types of events in the Annexes, and suitable Job Action Sheets.

Interagency Cooperation

This role is a prime candidate for interagency cooperation. Under normal circumstances, each organization which is responding to any incident will have specific elements of inventory, either in its possession or under its control, about which the other organizations have little or no knowledge. The bringing together of all of the Logistics Chiefs from all agencies into an interagency Logistics Task Force may facilitate improved access to, and flow of, resources among the participants. To illustrate, a hospital may be able to access a municipal snowplough from the Public Works department to clear the driveways and approaches to the hospital during a snowstorm, or the hospital’s Dietary department may be able to establish a mass-feeding operation for first responders in the hospital cafeteria. These are but two examples, and the list of potential examples of the benefits of such a Task Force are significant.

Finance Chief

Figure 3.13 The Finance Chief with subordinate roles

Sometimes described as “Accountability” or “Administration” in some Command-and-Control models, this role is responsible for the approval, tracking, and payment of all costs associated with the response to the incident. It typically holds any petty cash resources, and it will approve any purchases or expenditures. This role is responsible for the continuous tracking of response costs of all types, and for the provision of both interim reports on costs incurred, and total costs of response to the incident.18 Typical subordinate resources include Staffing Costs, Accounts Payable, and any Workers’ Compensation issues. While it may not be necessary for the Finance role to have a continuous presence in the Command Center, they must remain readily available to consult with the Incident Manager, and their participation in the Business Cycle meetings is essential.

Selection

Every hospital has individuals who perform such functions on a daily basis. Such individuals are the obvious candidates to fill such positions during a crisis. Appropriate candidates for this position include the organization’s Chief Financial Officer, supported by senior Accounting staff. Sufficient depth is required in this role to support 24-hour operations, if required. Subordinate functions are appropriately run by senior staff from the Purchasing, Accounts Payable, and Payroll departments. As with most positions, provisions should be made for the roles to be filled by “ad-hoc” staff, until predesignated staff can arrive. These would include appropriate provisions in the Emergency Response Plan, as well as appropriate Job Action Sheets.

Interagency Cooperation

Despite the fact that this role is absolutely essential to the successful operation of the Command-and-Control model and the response to the incident, it remains purely internal. There is no ongoing requirement for interagency collaboration in this function. Work with other agencies will probably be required subsequent to the conclusion of the event, particularly in dealing with various levels of government with regard to the potential recovery of the hospital or healthcare agency’s response costs.

There are, in any crisis, those who may be described as its “unsung heroes.” These are often roles which do not appear in any organization chart, but they are nonetheless absolutely essential to the success of the response.19 While the Incident Manager and the Incident Management Team will be lauded, both the smooth functioning of the Command Center which made this result possible, and the exceptional documentation of decisions, events, and actions which protect the organization after the event, are likely to be overlooked. While many unsung heroes will contribute to the response, there are two in particular which deserve special mention, and which should be predesignated.

The Scribe

In any type of major incident response, the creation of appropriate and detailed documentation is essential. Every event and action, each discussion, and every decision must be documented. This includes actions which were considered, but not enacted, and also the reasons for each decision, where possible. In most jurisdictions, if such documentation is created at the time of the event, and if that documentation was created as a duty of the individuals involved, it is highly likely that all of it will ultimately prove to be admissible in any coroner’s inquest, public inquiry, criminal or civil proceeding, which may follow the event itself. Such information is also invaluable for post-event analysis and problem-solving, and for the education of both team members and other staff following the event. Additionally, the Incident Manager will require assistance with the creation of a formal, written, Incident Action Plan, periodic Situation Reports, and an After-Action Report.

As essential as all of this information is, the Incident Manager simply does not have the time to generate all of it, and still manage the incident effectively. The creation of such information is the role of the Scribe. The position of Scribe is not simply required during Business Cycle meetings; wherever possible, it should be a permanent position, and the Incident Manager and the Scribe should be “joined at the hip,” virtually inseparable. The duties of the Scribe are essentially about documentation, in particular, about the creation of minutes for every meeting, whether formal or informal, that the Incident Manager attends. The Scribe should be someone with above average documentation skills; in particular, someone who is accustomed to recording the minutes of various meetings. Computer skills are essential, and, although quickly disappearing, the ability to take Shorthand notes would also be an asset. Good candidates for such a position are the Executive Assistants who normally work for the very senior members or an organization’s management team. Such positions should be predesignated, with both a primary person and multiple “back-ups,” in order to sustain the operation of the role during large or protracted events. While the Scribe will normally work with and report directly to the Incident Manager, the Office Manager position will normally provide administrative support.

Office Manager

Every Command Center requires someone operating discreetly in the background, ensuring that all of the systems and services operate exactly as they are supposed to; effectively and seamlessly. The simple truth is that the person in charge and the person who knows how to change the toner cartridge in the printer are rarely one and the same! The Office Manager ensures that all office equipment continues to operate effectively, ensures that telephones are answered, maintains the levels of office supplies, and coordinates the activities of those in Support Roles, so that essential maintenance and repairs can occur without any undo disruption of the Command Center business. The Office Manager should be someone whose day-to-day activities and expertise involve similar roles, and likely candidates are senior administrative staff personnel. The position, like those of the Incident Management Team, should be predesignated wherever it is possible to do so, with at least two designated “back-up” role candidates.

The role of the Office Manager is to ensure that the Incident Manager is free to concentrate on actual incident management activities, without the unnecessary distractions of the more mundane business operation requirements which are generated by every Command Center operation. There are many Command-and-Control models which have attempted to attribute such activities to the role of Scribe. Unfortunately, however, if the Scribe is doing that job correctly, there is unlikely to be sufficient “spare” time to adequately perform all of the Office Manager’s duties. While not a critical position in all responses, during large or protracted responses, the presence of such a role can be an invaluable asset to the Incident Manager.

Support Roles

Many types of systems include those people who operate in the spotlight, and also those who operate quietly in the background, usually making the contributions of those in the spotlight possible. In crisis response, they are often the “unsung heroes,” and while they may not be acknowledged during an actual event, it is certainly appropriate to recognize those contributions here. The following roles are not specific components of any Command-and-Control model. They are, however, support services which are essentially quite important to the successful operation of the Command-and-Control model. As such, the need for each of these services, and the source for such services during any crisis, require advance consideration by any Emergency Manager who is operating in a hospital or healthcare setting.

Security

While Security staff have day-to-day roles in virtually every hospital; there are specific requirements during any type of disaster, which will need to be considered, and provided for in advance. These will include an additional presence in the Emergency Department, and additional assignments to control unauthorized access to the Hospital Command Center, the Media Information Center, and the Family Information Center. These measures are required to prevent any disruption of essential processes such as patient treatment and decision making, which are essential to the successful response to the crisis; essentially by controlling the movement of individuals of various categories, including the media, distraught victims, and also distraught family members. It is not uncommon during any large-scale crisis for the security requirements in a hospital to double, or even triple from normal staffing levels.

Computers are wonderful … when they work. Computer technology has moved the evolution of Command Centers forward dramatically in the past decade, particularly in the hospital/healthcare sector. The information which this technology can provide has become absolutely essential to the successful resolution of an incident. The problem is that, particularly in the healthcare sector, those using this technology are not what might be described as “expert” users. In order to use the technology, some level of expertise support is usually required. This is particularly true in the hospital/healthcare setting, where the Command Center is rarely purpose-built, and requires the assembly of its technologies within an improvised space.

Expertise is not only required for the assembly of the equipment. It is also required for the provision of access to an established network, or the creation of a temporary, secure network (the Command Center), whether by Ethernet or a Wi-Fi system. It is also needed for the registration and authorization of individual computers and peripherals, such as printers, on that network. Levels of authority and permitted uses of the system may also change during a crisis. Systems, which under normal circumstances severely limit Internet browsing, may need to change this for selected individuals during any crisis. Activation of disaster-specific software, or even simple repairs to computers and peripherals, may also be required.

For the computer network to be truly effective in a Command Center setting, it must appear to be as “seamless” as possible to the end users of the Incident Management Team. This is the role of Information Technology. Fortunately, most hospitals have such individuals on staff, in order to maintain the operation of their internal networks on a daily basis. In smaller organizations, such services may be provided by contractors. It is essential for the Emergency Manager to ensure that such services are available to the Command Center, either within the facility or with rapid access (within 1 hour), around the clock. Such individuals will normally fall under the supervision of the Office Manager, during any crisis or incident response.

In any hospital, telecommunications systems are becoming increasingly complex. This may be further complicated, as many hospitals have migrated from conventional telephony to Voice Over Internet Protocol (VoIP) telephony, in search of operating cost savings.20 In a purpose-built Hospital Command Center, this would be addressed by the simple, onetime, installation of the appropriate telephones, which are then left in place until needed. Most hospitals, however, do not have such a luxury, and the Hospital Command Center will occupy a multiuse, improvised space for the duration of the response. It may be possible to preinstall telephone jacks in the walls, but the actual installation of the telephones and the activation of the associated phone numbers requires specific expertise. If the hospital uses a conventional telephone system, they should have an arrangement for an emergency response by the local telephone service provider, in order to make the necessary installations. In the case of VoIP telephony, it is likely that this role has already been transferred to the hospital’s Information Technology staff, or to a contracted service provider. The ongoing presence in the building, or within a maximum one-hour response time, of at least one individual with the appropriate expertise is essential to a successful Command-and-Control model.

Housekeeping

The maintenance of a stress-free environment is important, if not essential, to an effective Command-and-Control model. It has been proven that the absence of litter, and of other forms of disorganization, actually contributes to a reduction of the stress levels of a work environment. This is specifically what the hospital’s Housekeeping staff does every day. The maintenance of the environment in the Hospital Command Center is probably not on the daily work schedule, and it will need to be added. Additional attention will also be required in any Breakout Rooms or staff feeding/rest areas which are associated with the Hospital Command Center operation. In addition, the required cleaning and tidying will need to be scheduled so as not to disrupt either Business Cycle meetings or other high-priority activities in the Hospital Command Center. A clean workspace is a low-stress workspace, and your Incident Management Team will thank you for it.

Dietary

In any hospital or healthcare agency which is involved in a crisis, the challenges to Dietary staff, and also their major contributions, focus on two specific areas. The first of these will be a dramatic increase in the population of the facility, which may continue over the long term. This can be a challenge with respect to planning, since most hospitals operate on a “just-in-time” basis, with respect to food delivery. This is a major potential issue, for which the Dietician may serve as an expertise resource for the Incident Manager and Logistics functions.

The second key role is the care and feeding of staff who are responding to the crisis; in particular, the Command Center staff. From personal experience, the longer an event runs, the less attractive pizza and other fast food become as eating options. Hospitals are fortunate, in that, unlike communities, they normally have trained Dieticians on staff, who can support Logistics through the creation of a feeding plan which provides variety and balanced nutrition.

Conclusion

Within any hospital or healthcare agency, the management of the response to any type of incident is always a team effort. This teamwork must flow from the Incident Manager, through the Command and General Staffs, to their subordinate staffs. Beyond those obvious roles, that teamwork must continue on to those who play often unseen but nevertheless essential support roles and services which permit the entire command and control model to function as effectively and as seamlessly as possible. Without such a coordinated effort, no Command-and-Control model, no matter how well thought out, will function to its fullest potential.

As with so many aspects of the practice of emergency management in a hospital or a healthcare facility, the key is to plan in advance for as many potential events and needs as possible. By making the appropriate assignments and arrangements, and by establishing the appropriate resources and the methodology for accessing them before the crisis begins, the Emergency Manager is much more likely to be able to ensure that the response to that crisis will be successful. Hospitals do this all the time; you have never seen a hospital wait until a patient was in a medical crisis before beginning to assemble a “crash cart.” As we have learned, even the Command-and-Control model is nothing new; whether or not it has been called the Command-and-Control model, variants of this technique and its associated roles are already common within healthcare settings. Planning in a pro-active mode is almost always more effective than planning in a reactive mode. This philosophy should be reflected in the daily activities of the Emergency Manager, as well.

The key to success is for the Emergency Manager to ensure that all Incident Managers and their immediate support staff on the Incident Management Team are pre-identified wherever possible and are provided with the appropriate training and opportunities to practice the methodology. In the best traditions of emergency management, each Key Role appointment should be supported by multiple “back-up” appointments, in order to ensure both continuity and the depth required for “around the clock” and protracted operations. Specific provisions must also be made for the provision of services outside of normal business hours, through the use of “ad-hoc” staff with appropriate, preestablished, supports in place. It is, after all, a hospital, and there is a legitimate expectation that it can respond quickly and effectively to a crisis, even outside of business hours.

The development and the use of an effective Command-and-Control model can be the difference between success and failure for a hospital or a healthcare agency. To do so, the time and effort required for its creation and full development must be invested in advance, through planning, training, and ongoing dialogue with other healthcare partners and with the response agencies which, just as the hospital, serve the community. The hospital may not be considered to be a “first responder,” but it is without doubt a “first receiver,” and, as such, its successful application of the principles of command, control, and effective interagency coordination are likely to be an essential component of any community’s response to a crisis.

Student Project #1

Select a healthcare-specific command and control model, either the HICS or the HECCS. Looking at the organizational chart for a particular hospital, select one primary individual and two backups for each of the Key Roles in the model. Selection should be based on knowledge, skills, and day-to-day responsibilities. Explain and defend your rationale for each selection. Ensure that your work is appropriately cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate level of research has occurred on this project.

Student Project #2

Select a single Key Role position, drawn from either the Command or General Staff groups. Identify all of the potential subordinate positions which might be required to support that position, in terms of its anticipated duties and role expectations. Now, looking at the organizational chart for a particular hospital, select one primary individual and two backups for each of those subordinate positions which you have already identified. Selection should be based on knowledge, skills, and day-to-day responsibilities. Explain and defend your rationale for each selection. Ensure that your work is appropriately cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate level of research has occurred on this project.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully and select the MOST CORRECT answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (eight correct answers) you should re-read this chapter.

1. In the Incident Command and Incident Management Systems, the group which is primarily tasked with the provision of support to the Incident Commander/Manager is called the:

(b) Command Staff

(c) Command Center Support Staff

(d) Key Roles Staff

2. The group which is primarily responsible for the provision of support to the Operations Chief is called the:

(a) General Staff

(b) Command Staff

(c) Command Center Support Staff

(d) Key Roles Staff

3. The primary advantage to the practice of predesignating those who will fill roles in the Command Center is that:

(a) Expectations are clearly understood

(b) Advance training is feasible

(c) Roles can be practiced through exercise play

(d) All of the above

4. In the early stages of a crisis, positions in the Command Center may be temporarily filled by untrained, “ad-hoc” staff through the use of:

(a) Instruction manuals

(b) On the job training

(c) Job Action Sheets

(d) All of the above

5. An arrangement in which staff from multiple agencies performing similar roles come together to an interagency response to a situation or issue is called a:

(a) Strike Team

(b) Task Force

(d) Action Team

6. In the HECCS model, support staff such as Security, Scribes, and Housekeeping, are under the supervision of the:

(a) Incident Manager

(b) Emergency Manager

(c) Office Manager

(d) Chief Scribe

7. In a Command-and-Control model, the role of the Planning Chief and subordinate staff is:

(a) The “mining” of information

(b) Analysis of information

(c) Creation of short-term plans

(d) All of the above

8. The primary role of the Incident Manager is that of:

(a) Chief strategist

(b) Chief tactician

(c) Researcher

(d) Mediator

9. In the Incident Management System and HECCS models, a unique feature of the Safety Officer role is that it may be filled by:

(a) Different individuals as the incident evolves

(b) Different individuals with specific expertise

(c) Someone from an outside agency

(d) All of the above

10. The primary responsibility of the Operations Chief in a healthcare setting is:

(b) Organizing the Command Center

(c) Conducting the core businesses of the organization

(d) Directing staff in disaster operations

Answers

1. (b) 2. (a) 3. (d) 4. (c) 5. (b)

6. (c) 7. (d) 8. (a) 9. (b) 10. (c)

Additional Reading

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics covered in this chapter:

Canton, LG. 2007. Emergency Management: Concepts and Strategies for Effective Programs, John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN: 0470119756, 9780470119754

Haddow, G., J Bullock, J, Coppola, D 2013, Introduction to Emergency Management, 5th Ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, New York, ISBN: 9780124077843 eBook ISBN: 9780124104051

Lindell MK, Prater C and Perry RW 2006, Wiley Pathways Introduction to Emergency Management, 1st Ed., pp. 278, John Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN: 978-0471772606

Molino, Jr., L.N. 2006. Emergency Incident Management Systems: Fundamentals and Applications, Wiley & Sons, New York, ISBN: 9780470043417

Purpura, P. 2011. Terrorism and Homeland Security: An Introduction with Applications, Butterworth-Heinemann, ISBN: 9780750678438, 9780080475417

USHHS 2012, What IS an Incident Action Plan?, Public Health Emergency website, operated by US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC, www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/pages/appendixc.aspx (accessed March 07, 2014).