Introduction

Any healthcare facility is a complex structure, and centralized coordination of activities is essential to its operations on a daily basis. This is even more true when a disaster of any type occurs. Whether the event generates a surge in demand for services, disrupts supply chains, or forces the partial or full evacuation of the facility, strong central control is essential to the successful resolution of the incident. Municipalities, state and provincial, and federal governments understand this, and many have purpose-built facilities, or, at a minimum, a predetermined process for the assembly of such a facility, using a space which has been pre-identified and equipped in advance. Hospitals and healthcare facilities require such facilities, but the pre-identification of sites and their advance preparation are often inadequate.

This chapter will address the requirements for such a Command Center. It will examine and explore the most common designs for Command Centers which are currently in use. We will explore both the equipment and the personnel required to both run such a Center, and to provide robust supports for its operations. Operating procedures for Command Centers will be explained, including the use of the Command-and-Control model and its roles. Finally, barriers to the successful creation of such a Command Center for a healthcare facility will be explored, along with the strategies which may be used to overcome these barriers.

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter, the student should be able to explain the role and purpose of a healthcare facility Command Center, how it operates and how its activities can be integrated with those of other healthcare partners and the community at large. The student will also understand the routine operating and reporting procedures for any type of Command Center. The student should be able to describe the various types of Command Center designs which are available for use in a healthcare facility, along with the strengths and weaknesses of each. The various roles within and supporting Command Center operations will be understood, along with the equipment and support services required to support the Command Center’s operations.

Role and Purpose

The Command Center, within any type of healthcare facility, is intended to fulfill several functions. The first of these is to provide a designated meeting point and workspace in which those in charge of the response to the emergency may meet and work together in order to resolve that emergency.1 It provides a centralized “nexus” of information flow, so that all essential information related to the emergency event flows through a single point. It must be remembered that the “currency” of disaster management is information, and that the availability of the most comprehensive and best possible information is absolutely essential to the process of making the correct decisions to guide the facility through the emergency.2

The operation of the Command Center also provides for a standardized and regular process by which to manage the emergency, including the gathering and distribution of resources, analysis of information, development of strategies, and coordination with other healthcare providers and outside agencies.3 It permits the treatment of the resolution of the incident as a project, with project management skills and techniques coming into play; it ensures one plan, forging consistency and eliminating conflicting direction to staff.

The Command Center provides a single, central point upon which all individuals and agencies can rely for information and guidance.4 There is only ONE place to take a question, or a problem, and only ONE source from which work direction flows to frontline supervisory staff. This provides tremendous consistency. It also ensures that absolutely EVERY occurrence, decision, direction, measure, or activity is thoroughly documented in a manner which will help to make such activities defensible, should this be required after the fact. A standardized, fact-based decision-making process is essential to protecting the facility from claims of malpractice or liability once the emergency is concluded. It is a process which both generates and guarantees the ability to demonstrate that, in all reasonable matters, due diligence has occurred.

Challenges to Command Center Creation

The challenges to Command Center creation within a healthcare facility are generally due to four factors. The first of these is the lack of space for purpose-built facilities. The second challenge is generally intense competition for a limited budget. The third is that the Command Center project is rarely seen as a part of the “core-business” of the facility, and is focused, at least in the minds of decision makers, on an issue which, hopefully, “might never happen.” These challenges can make a Command Center project a very difficult “sell” for the Emergency Manager in a healthcare facility. Each of these will be examined independently.

The challenge of space availability is often due to the fact that space within a given hospital or healthcare facility is generally at a premium, and the competition for such spaces by competing departments is generally intense. Space usage within hospitals is generally driven by the evolution of medical technologies. Given the high cost of new construction, the process tends to be limited to the existing four walls of the hospital building, and the competition within that space becomes intense. Generally speaking, a given iteration of technology, a CT scanner, for example, usually has a useful life expectancy of about five to seven years, before advances in technology render it less than “state of the art.”

Such devices are generally on a plan, at least in the minds of the users, of scheduled replacement. One of the challenges with this is that in order to maintain services while the technology is upgraded, it is generally necessary to install the new technology in a second space, while the older technology continues to provide service until the new equipment is completely tested and ready to replace it. For this reason, even when a given space might appear to be available, there is an excellent chance that some Department has already earmarked it for their next round of expansion.

It may be prudent to at least attempt to look at the expansion and service relocation plans of various departments, and to attempt to secure a space which one of them is already planning on vacating; this is much less likely to incite resistance to space allocation, particularly when they were already planning on vacating the space. It is also likely that a multipurpose space, usable on a daily basis as a classroom or a boardroom, and quickly convertible into a Command Center, is much more likely to be well received, than a proposal for a full-time, dedicated facility.

Budget is another of the challenges with approval of a Command Center project. Whether publicly or privately funded, healthcare facilities have limited financial resources, and, as with space allocation, the competition for these resources is usually quite intense. Most evolution of healthcare facility space usage tends to be project-driven, and in most cases, Department Heads are masters at this process. They are aware of the evolution rates in their respective technologies, and usually operate their own project/proposal timelines based upon the known rate of technological evolution. As a result, the creation of the research required to craft an appropriate proposal for the next project, including space allocation and budget, generally begins within days of the latest iteration of the technology beginning to operate.

Such proposals tend to be extremely detailed, with explanations of technology, projected service demands, needs assessments, and risk management decisions, all supported by immaculate research, and all in place as a highly credible and concrete proposal, before the document ever sees the light of day. The combination of these factors mean that it can be difficult to persuade the allocation of such space for a dedicated project which, even the Emergency Manager hopes, will be used only rarely. This is particularly true when the Emergency Manager crafts their own proposals on the old-fashioned “what-if” scenarios, instead of using the comprehensive research and project planning skills used by their competitors. The only real solution to these problems is for the Emergency Manager operating in a healthcare setting to acquire the same essential skills, such as applied research methodology and project management,5 Lean for Healthcare and Six Sigma, and to apply these diligently, in order to produce proposals which are of competitive quality.

Command Centers may consist of purpose-built facilities, which are somewhat rare in the healthcare setting. They may also be improvised facilities, or a hybrid combination of these two factors. When not purpose-built, they may function on a “push” or a “pull” assembly process. There are a variety of potentially effective design layouts, and a number of support facilities, resources, and staff which will be required. Each of these factors will be explored in detail in the following pages.

Purpose-Built

A purpose-built Command Center is a dedicated space in which all of the elements and technologies required to manage an emergency remain assembled and operational on an ongoing basis. All that is normally required is for the Command Team to report to the designated facility and begin the management process. Such facilities usually maintain a rota of on-call Duty Officers, whose job is to ensure that all resources and equipment are in place, regularly tested, and ready for use. The Duty Officers may also perform an active monitoring function regarding events happening nearby and likely to affect the Command Center. Such facilities are fairly common among large cities and the higher levels of government, but are something of a rarity in healthcare, for reasons which have already been discussed.

While such Command Centers are the ideal, they are also difficult to justify in terms of expense, except in a very large organization. Consider the cost of purchasing a dozen or more computers and peripherals, assembling them in a network, and then never using them other than for training purposes or an actual emergency! This is typically beyond the means of small municipalities, to say nothing of the budget challenges which would face a hospital. Such dedicated facilities are not at all portable, and when one considers that one of the fundamental principles of emergency management is multiple layers of redundancy, it may well be that building an expensive dedicated primary Command Center but lacking the funding for a similar off-site backup Command Center, is a relatively perilous risk management choice.

An improvised Command Center employs some other facility which has another purpose in daily use, and which is only occasionally converted to Command Center usage. The equipment required for Command Center usage is either securely stored within the designated space, or is securely stored elsewhere, and requires transportation to the improvised site. In either case, the resources required, including computers and peripherals, telephones, radios, televisions (TVs), office supplies, and occasionally, even furniture, will require assembly, testing, and in some cases, connection to a network, whether computer or telephone, before they can be used. These are typical in smaller municipal governments and also quite commonly used in hospitals and other types of healthcare facilities. In a healthcare setting, such improvised settings typically employ boardrooms, hospital classrooms, or similar locales.6 While they do require assembly time (how much depends on how you design them) and technical support to operate, they tend to be much less expensive, since a great deal of the equipment, and certainly the space, are being used for other purposes on a daily basis. The most significant advantage to this design approach is the ability to simply pick up and move all equipment to a back-up operating site, should the use of the primary site be denied by the effects of the incident.7

Hybrid

A hybrid Command Center is a design in which the principles of an Improvised design still apply, but one in which much of the underlying infrastructure has been put in place in advance. The room may look to all who see it as a very ordinary, everyday boardroom or classroom. However, concealed in the walls and ceiling are additional telephone lines and jacks, emergency electrical power plugs, a wireless router for the computer network, and so on. The room may also have wall or ceiling mounted flat screen monitors, which are used on a daily basis for teaching, but which readily convert to display essential information to Command Center staff, when required. Such facilities often also provide for the discreet, secure storage of all other Command Center supplies.

Such Command Center designs can typically activate much more quickly than the traditional Improvised approach, because they are essentially “plug and play.” They are considerably more difficult, however, to relocate, should the use of the primary site chosen be denied to the Command Center staff (e.g., fire). In any multiuse facility, the space will require regular monitoring and clarification of “ownership,” since it is not uncommon for other users to assume that since they use the space regularly, they can re-allocate such items as telephone lines, or place an essential daily system on the computer network router in the room, without any prior consultation.

“Push” Systems

An assembly system for either the Improvised or Hybrid model in which essential Command Center equipment is stored elsewhere in a secured location and then brought to the assembly site when required is called a “push” system. Such systems typically employ a locked box system (one or more boxes for each function in the Command Center) in which boxes of equipment are inventoried, then sealed, and placed where no one has access to them other than for inspection purposes, and in which any attempted interference with the contents will be immediately evident.

The contents of each box will vary according to the role of the individual using it. In any IMS-based command and control model, for example, the box for the Logistics Chief is likely to contain a list of essential equipment and resource suppliers, along with 24-hour contact instructions. Similar boxes would exist for each role, and for any other essential Command Center staff. Other boxes might contain a “starter kit” of essential office supplies and blank forms upon which the Command Center will operate.

In such Command Center kits, these boxes are typically secured inside of lock-able wheeled carts, which are themselves secured within a locked space. Access to these locked spaces is limited, usually to only the Emergency Manager and to hospital Security. This permits the monthly inspection of the kit, without making it available for “pilfering” by those who believe that they require the equipment more than the kit does. When requested, the cart(s) are simply removed from their secured space by Security or some other group and brought to the designated assembly space, where they are then unloaded, and the Command Center assembled. Once empty, the boxes and carts are returned to their secure storage location, where they are out of the way.

The biggest single advantage of such a system is its portability. It can be readily transported to the predesignated site. However, should the nature of the emergency deny the use of that site, it can be readily transported to an alternate operating site elsewhere on the campus. It can even be simply loaded onto a truck or van and relocated to a designated off-site alternate operating location, should events dictate that this step is needed. This permits healthcare facilities to embrace the principle of multiple layers of redundancy.

“Pull” Systems

In some Improvised, and many Hybrid Command Center designs, a system in which all of the required Command Center supplies are kept in locked cabinets within the designated space is generally called a “Pull” system. The boxes themselves may be similar to the “Push” system, or they may consist of a single, locked cupboard for each essential role in the Command Center. When required, the cupboards are simply unlocked, the equipment “pulled” out, and assembled. While this results in faster assembly and activation of the Command Center, its lack of portability generally precludes the use of the equipment at an alternate operating site, should this be needed. That being said, the author has seen one particularly inspired design in which the wheeled carts were locked in a closet in the designated space, providing the best elements of both design approaches.

Design Considerations

The Command Center is, by definition, a high-stress environment. Given that most of the occupants are likely to be “Type A” personalities, and already under elevated levels of pressure, any design approaches which can be used to mitigate stress levels will be essential to the successful use of the site. General principles of ergonomics do apply,8 and if an ergonomist is available, they can make substantial contributions to the design of the environment. At a minimum, lighting, heat and air exchange, ambient noise levels, comfort of workspaces, and security are essential elements to consider.9

With respect to lighting, this factor can, by itself, significantly reduce stress levels for the occupants of the Command Center. At a minimum, try to avoid the use of blue-spectrum lighting, whether fluorescent or compact fluorescent, as this has been demonstrated in studies to elevate stress levels. Full-spectrum or yellow-spectrum systems have been proven to be less stressful. Consider the potential for variable level lighting, if available. This can be used to eliminate the stresses caused by continual high light level exposure on the effects of the natural Circadian rhythm. Dim the lights during evening hours, if the operation is around the clock. Ensure that the individual task lighting provided for each designated workspace is sufficient to eliminate unnecessary eye strain, while remaining adjustable to personal preferences.

The ideal work environment is neither too hot nor too cold, and should be, if possible, adjustable to individual preferences. Always bear in mind that those assigned to work in this space may very well be there for an extended period of time. While short-term discomfort can be overlooked, long-term issues of environmental comfort will affect cooperation and collaboration. Other factors which are equally essential are humidity and air exchange rates. An environment which is too humid is clearly uncomfortable, and poor air exchange results in poor air quality and a “stuffy” environment which may even contribute to conflict between the occupants of the room.

Consider the effects of ambient noise on the ability of participants to share information and collaborate. Have you ever been in a large meeting which was poorly run, in which multiple conversations were occurring at the same time, and where external noise to tended to wash out the amount which you could actually hear? Consider the need for breakout rooms for sidebar conversations. Also ensure that any telephone in the Command Center is equipped with the ability to turn off the ringer, and to rely instead of a flasher to identify incoming calls. That being said, no telephone in a Command Center should EVER be equipped with voicemail; every phone must be answered by a human being in order to ensure that no essential information is overlooked or delayed, even during a Business Cycle meeting. TV screens, while they provide essential information, should have the volume switched off, and closed captioning employed. When dynamic monitoring is essential, it should occur in a location away from the main Command Center space. Similarly, when monitoring two-way radio communications (e.g., emergency services), this activity should occur away from the main Command Center.

Consider the ergonomics of the individual workspaces. Have you ever had to sit on a hard wooden chair for an extended period of time, or had to work on a work surface which was either too high or too low, or poorly lit? Consider the effects of such variables on the occupants of the Command Center over a period of DAYS. Wherever it is possible to do so, individual chairs and work surfaces, while they cannot be personalized, should at least be adjustable. While the main meeting table in the Command Center is of a fixed height, this can and should be avoided in those spaces where staff are working between meetings. Also ensure that provisions are in place to regularly clean and maintain the Command Center, even while operations are ongoing. While coffee and drinks can be permitted, actual eating should occur elsewhere, away from the stressful environment. Similarly, waste baskets should be emptied, and work surfaces wiped down regularly. A clean and healthy environment can go a long way toward the reduction of stress levels for the occupants of the Command Center.

Security of the Command Center is also an essential issue requiring consideration. The access to the Command Center should be available ONLY to those who are actually working in it. There is an old adage among Emergency Managers which says that three categories of people will come to a Command Center; those who are assigned to it, those who are certain that they have something essential to contribute, and the tourists! Nothing will disrupt the business flow of a Command Center more quickly than large numbers of individuals wandering in and out, destroying the flow of the Business Cycle. Subordinate staff, and for that matter, unassigned superiors, should be denied entry, and, if their information is important enough, met in the corridor or a breakout room. Nothing should be permitted to disrupt the Command Center process. This does not mean that the Command Center is not accountable to the senior administration of the facility; simply that the required reporting should occur elsewhere, and at a time when it does not interfere with the management of the incident.

Another key factor of Security is the access to sensitive information. Where possible, try to avoid ground floor level meeting spaces, particularly those with large exterior windows. While natural light is a highly desirable feature for the comfort of occupants, it also provides a potential opportunity for curious members of the media to access any information posted on boards or walls, using cameras with long lenses, or to eavesdrop on your Command Center conversations using parabolic microphone technology which actually uses the vibration of the window to hear what is being said inside! As another factor, consider banning the use of personal cellular telephones in the Command Center, as most of these can be eavesdropped upon by the media. For sensitive information, ONLY landline telephones should be used. The same issues apply to both e-mail and text messages from cellular phones and some types of tablet computers.

No Command Center design is perfect, and each must, first and foremost, meet the needs of the organization creating it. In the end, the initial design will focus, in large measure, on the Emergency Manager’s best estimate of the organization’s needs from such a facility at the time of its creation.10 The growth and development of such a facility will be organic, often evolving each time that it is used, as weaknesses and shortcomings are identified, as technologies evolve, and sometimes, as the role of the organization using it evolves and changes.

Layouts

The first element which should dictate your choice of Command Center layouts is the Command-and-Control model which the facility elects to use. There are a number of different physical layouts which are used in typical Command Centers or Emergency Operations Centers of various types. At this point, the student will probably benefit from a review of Chapter 1, which deals with specific Command-and-Control models, with the review focusing upon the Hospital Incident Command System and Healthcare Emergency Command and Control System models. A further review of Chapter 3 in order to refresh the student’s memory on specific roles within each model will also be useful. While a number of different model layouts are presented here in order to provide examples of various options, it should be remembered that the specialized requirements and restrictions of the healthcare setting have traditionally resulted in a choice of some variation on the “Boardroom” layout.

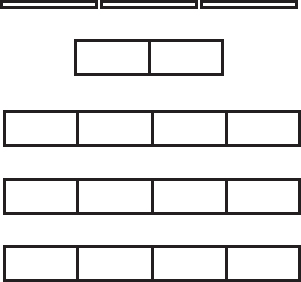

“Mission Control”

Figure 4.1 Mission control

The “Mission Control” layout is most often used in the Emergency Operations Centers of large Provincial and State Emergency Operations Centers. In this model, the layout is built around the ability to display critical information in front of the entire group, both with whiteboards, and, above these, flat screen TV screens, which can be used to display a variety of information, including data, PowerPoint presentations, videoconferencing with other sites, live TV coverage, and Internet-based information such as weather displays. As technology becomes more advanced, it is likely that live images from the scene of the incident, provided by either hand-held camera, “smart” phones or tablets, or even aerial drones, will become practical and feasible.

In this model, the Incident Manager and the Scribe are seated, facing all other members of the Command Team (Public Information, Liaison, Safety, Operations, Planning, Logistics, and Finance). Each of these is seated at their own workstation, with the ability to add information from their own computers to the overhead screens, to be viewed by the entire Team. By arranging the workstations in this manner, Team members do not need to relocate in order to attend a Business Cycle meeting. They simply look up and participate. Additional seating is provided for use by the Office Manager, Senior Management Team observers, and observers from outside agencies.

This layout is one of the older designs and was originally driven by the need for low profile linear connection of telecommunications, computer network, and power cabling. In doing so, it creates an environment which is very “information-rich,” without interfering in the team communications processes. The model requires a large, dedicated room, and typically provides more seating and workspaces than would be typically required by any healthcare facility. It is still used by larger government agencies, and by, among others, NASA.

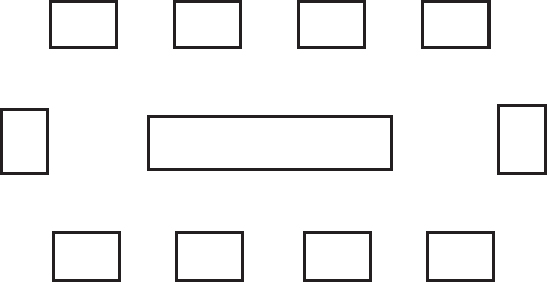

“Marketplace”

Figure 4.2 The “Marketplace” configuration

The “Marketplace” layout is typically found in improvised Command Centers and Emergency Operations Centers which are deployed in improvised spaces in smaller communities. These are often located in school gymnasia and municipal recreation centers, where the space starts as a “blank canvas,” with no wiring or cabling, and where everything must be set up “from scratch.” In this model, each key role in the Command-and-Control model “owns” one table or workspace, and individuals typically move from table to table, negotiating access to resources or other types of collaboration. When a Business Cycle meeting occurs, those in key roles typically gather around the large central table for the actual meeting. The challenge with such configurations includes the ability to share electronic information as a group, and the physical hazards associated with widespread electrical and telecommunications cabling, leading to trip and fall hazards, and the ability to disconnect all or a significant part of the entire system by simply tripping over the wrong cable. Such systems are also connected to emergency power sources only rarely, making them even more vulnerable. This particular design layout is rapidly falling from favor.

A typical marketplace configuration

“Bull’s-Eye”

The Bull’s Eye layout is most often used by larger cities which have chosen to use their local Council’s meeting chambers as an improvised Emergency Operations Center. This permits the seating of the Incident Manager at the center of the “Bull’s Eye” with all other Command Team staff arranged in a circle around him or her. It provides an additional advantage in that staff who are supporting either the Command Center or individual members of the Command Team may occupy the outer ring of the configuration as observers, can take notes or pass relevant information to their own Supervisors, who are actually participating in the meeting. Such systems have an advantage, in that all prewiring and cabling, emergency power and audiovisual displays are already incorporated into the layout because of its everyday uses. This model is most commonly used in larger cities, but may also be occasionally found in larger, university-affiliated teaching hospitals, who may employ a lecture hall for this use.

Figure 4.3 The “Bull’s Eye”

City Council Chambers, located in the City of Hamilton, Canada performs double duty as the Municipal Command Center

Figure 4.4 The “Boardroom”

The Boardroom layout is the most common configuration for Command Centers within healthcare settings. This usually consists of an adaptation of the hospital’s existing boardroom for the purposes of running the emergency. This configuration permits a good deal of audiovisual display, both on screens and on overhead video display. It also often includes videoconferencing equipment. If the boardroom has been well designed, emergency power is already present. In this model, the Incident Manager sits at the head of the table, usually with the Scribe at the opposite end. In between, all members of the Command Team are seated, along with any other interested parties or observers. A well-designed facility can include “invisible” low-profile workstations (gate-leg, fold up, resemble a chair rail) along the side walls, where Command Team members can work between Business Cycle meetings. In some cases, these are not included, and Command Team members work in their regular workspaces, subject to recall by the Incident Manager. Such facilities are already equipped with clerical support and office equipment, washrooms, and often, even a kitchenette. In some cases, even “artwork” is reversible, with whiteboards on the other side. By day, a prestigious boardroom, but by night … the Command Center. This layout is often the easiest “sell” for the Emergency Manager; most facilities require such a room in any case, and the multiple uses ensure lower operating costs. This is a classic example of an Emergency Manager considering multiple users in order to achieve a required objective.

The Emergency Operations Center, Deer Park, Texas. A typical “Boardroom” configuration. Note the individual workstations for the Command Team built into the walls

“Virtual”

A good deal of attention has been paid to the concept of the “virtual” Command Center. This is a logical follow-on of the software industry’s efforts to provide virtual conferencing and may very well be the “wave of the future.” At the moment, however, such systems typically lack the type of robust information sharing that occurs in a physical Command Center. They are also relatively insecure, with hackers, including, in some cases, the media, able to readily eavesdrop, if they know which system you are using. Finally, such systems typically rely on either the Internet services provided by local cable TV companies or telephone providers, or on the cellular telephone network. All of these systems are potentially subject to disruption by the effects of some types of emergencies, making such systems less robust than one might wish. That being said, they can be a useful tool for faster activation of the Command Center after hours, with half of the Command Team simply logging on and beginning to work from home when notified, while the other half proceed to the physical Command Center and begin activation. Once they are active, the virtual work from home is transferred, and the second half of the team reports to the physical Command Center. The flaws in such systems are continually improving; we are simply “not there” yet.

Information Display

Most modern Command Centers are designed around the ability to display information to the entire group. What was once a single, old-technology vacuum tube TV in one corner of the room has quickly become enhanced, multi-image display, with the ability to display information from several sources simultaneously? Most modern Command Centers are built around either a single projection screen at one end of the room (and this is becoming obsolete) or a bank of flat-screen monitors, typically in the 42-in. range, arranged near the ceiling at the head of the room, or, when money is no object, around the entire room. Such screens can be used to permit videoconferencing, information from local broadcast news sources, Internet-based data such as weather forecasts, CCTV footage from your own facility, or presentations such as PowerPoint and other types of data from various members of the Command Team. Ideally, such screens are volume controlled, in order to eliminate unacceptable levels of ambient noise, with dialogue typically replaced by closed captioning.

In the most elaborate versions of such displays, a touch-sensitive screen is configured as a tabletop, with a base (raster) layer of the community map or institutional floor plan, and the potential to overlay literally hundreds (how many depends on you) of layers of additional information, in order to see relationships between data sets and to employ these for planning purposes. In the most elaborate versions of such tools, viewers can actually overlay real-time information, such as the GPS-based tracking of moving emergency vehicles, with other types of information, such as a plane crash location, flood waters, forest fires, population centers, and so on.

The more basic versions of such technology are no longer particularly expensive, although the system just described might cost tens of thousands of dollars. Digital TVs have largely replaced the old vacuum tube devices, which are obsolete, difficult to repair, and should be replaced at the earliest opportunity. Also, flat screen technology is more amenable to the conversion from analog to digital TV signals, which is currently well underway around the world. The more modern flat screen TVs have actually become less expensive than the older technology. Increasingly, “smart” TVs, based upon the Android operating system, can provide an entirely new depth to displayed information, with multi-image display, and incorporating live TV signals, closed circuit TV images, computer-generated images and data, and videoconferencing. The ability to display large volumes of information from various sources can be accomplished with relative ease, using your institution’s own information technology professionals, and such arrangements should be made as simple and user friendly as possible.

Some of the technologies which, at this writing are literally just over the horizon, are the ability to monitor your own facility and property from the air, using small, inexpensive, unmanned drone aircraft. Some emergency services are also experimenting with this technology, and it may soon be possible to actively observe the effects of a communitywide emergency in your own Command Center, using Internet-based video feeds from your local emergency services. The key to all of this is to buy the best technology that you can afford for your Command Center; it is likely to remain current longer and will do far more than bargain-priced equipment.

Telephony

Telephones are an essential component to any Command Center operation; the currency of disaster management is information, and telephones are often the primary and most reliable source. When establishing a Command Center, there are fundamental elements of telephone technology which the Emergency Manager needs to understand and employ in the planning process.11 In order to address this, we will examine each type of telephone technology, along with its relative strengths and weaknesses. We will begin with the elements of a telephone handset, then examine how networks work, and finally, examine different types of telephony technology.

The first thing which the Emergency Manager needs to understand is that old-fashioned analog telephones draw their operating power from the telephone line, while modern digital telephones, despite all of their push buttons and flashing lights, do not. When power goes out, analog telephones should continue to operate, while only those digital telephones which are connected to emergency power sources will continue to operate. When designing the Command Center, since digital telephones are almost exclusively the choice of handset, it is essential to ensure that there are enough emergency power outlets in the Command Center to provide power to the telephones, in addition to everything else. As a variation on the theme of multiple layers of redundancy, it is always a good idea to keep a few analog telephones around.

Local handsets in the Command Center should be equipped with flashers to indicate incoming calls, and with the ability to silence the ringer, in order to reduce ambient noise levels in the Command Center. No telephone in a Command Center should EVER be equipped with Voice Mail … there is a natural and unfortunate tendency to ignore phones during meetings and let Voice Mail deal with them. The problem with this is that access to critical information can be lost, or at minimum, substantially delayed; phones should ALWAYS be answered in a Command Center, even during the Business Cycle meetings.

The Emergency Manager should also consider blocking the outgoing Caller ID function on all telephones in the Command Center and instituting a single number for incoming calls. This provides a single point of contact, which can be monitored, and the calls transferred accordingly, regardless of what is happening in the Command Center, and permits the taking of messages. Blocking outgoing Caller ID ensures that every number in the Command Center does not become an incoming line, as people become aware of the number. This way, Command Center staff will always have access to protected outgoing lines with which to conduct their business and work direction.

Cellular telephones (tele mobiles) are NOT a suitable substitute for landline telephones. Bear in mind the principle in emergency management of multiple layers of redundancy, with each backup system being technologically independent of the system which it is intended to replace. A cellular telephone is simply a two-way radio from the user to the nearest cellular tower; beyond that, the system relies on the same telephone network as every conventional telephone in the hospital. If one isn’t working, the other won’t work either! Satellite telephones are a suitable replacement but tend to be hideously expensive to acquire and use. As a result, while having a few is a good idea, ensure that you have suitable controls on their use.

Increasingly, hospitals and other healthcare facilities are moving away from conventional telephony, and toward Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) telephony for their internal networks. This is driven, in large measure, by the cheaper operating costs of VoIP systems. This means that the hospital telephone network is directly dependent on the same internal IT network, and on the hospital’s Internet service provider. When computer networks go down, phones do as well, and vice-versa. If the Emergency Manager has any input into such decisions, your facility should be encouraged to maintain at least a few conventional telephone lines, providing a backup system which is technologically independent of your primary telephone system.

Other things to know about telephones, include the pay telephones located in most hospital lobbies and Emergency Departments. Even when the hospital converts to VoIP, these telephones, which do not belong to the hospital, but to the telephone service provider, will generally continue to operate even when the VoIP system has failed. Even when the facility is still using conventional telephony, such phones are often on a different exchange from the rest of the building. The simple truth is that the local telephone company has two types of revenue: monthly bills and fee for service. Monthly bills get paid whether the service is interrupted or not, while fee for service systems, such as pay telephones or long-distance services, generate no revenue when not in use. The telephone companies understandably repair these systems first! A telephone dial tone is a courtesy signal … it is NOT essential for the telephone to operate. As a result, if the line seems dead, try dialling anyway … it might just work! Also, if no other telephone in the building is working, try the pay phones. Finally, even when a local call will not go through, try a long-distance call … they are separate systems, and in most telephone companies, long distance service is typically repaired first.

When considering radios, there are two separate and distinct approaches which must be considered. Each has its own uses, and each will be considered separately. The first of these is the use of simple radio receivers to monitor the events which have generated the emergency. This may consist of commercial radio and TV news coverage, or it may employ digital scanner-type devices to actively monitor (with permission) emergency services radio frequencies. The second is the use of two-way radios for actual communications. These may be the facility’s own radios, usually walkie-talkies, or may bring the facility into a more elaborate communications network.

The monitoring of commercial radio and TV for information about an emergency is a long-standing practice, but one which is gradually disappearing. At one time, the local radio station was staffed around the clock, had its own newsroom and reporters, and provided information to the community in real time. Those in emergency management, and in the local hospital, could actually call the station and ask them to broadcast requests for off-duty staff to report to work and so on. This was seen as a part of the station’s community service obligation. As technology has evolved, local radio stations have been forced to evolve as well, as a matter of survival.

In many cases, certainly in smaller centers, but in some cases, in larger centers as well, the “local” radio station has become partly or fully automated. Music and programming, including news coverage, are purchased from a national service, and the last part of the station to actually operate locally may well be advertising sales. Unless your emergency makes national news, you will hear nothing about it on your local station, and broadcasting requests for staff to report to work, or asking the public to avoid an overwhelmed Emergency Department are now technically impossible. For this reason, it is essential for the Emergency Manager to engage in dialogue with the local radio station(s), in order to understand exactly how they work, and what they can and cannot do. If the local station is fully automated, there is little point to monitoring it.

The monitoring of TV stations can be helpful to obtain information regarding external emergencies. That being said, it must be remembered that this is true only of local TV stations. Unless a disaster makes national news coverage, no information is likely to appear on national sources, such as CNN (United States), CBC News Network (Canada), or BBC News (UK), and if it does appear, it is often two or more hours out of date, and therefore of little interest in the management of the incident. In those cases, in which the TV station provides regional coverage, but is not located in the same community as the hospital, the Emergency Manager should anticipate at least a one-hour delay before any meaningful coverage commences, bearing in mind that reporters and camera crews must physically travel to the incident before they can begin to cover it.

The passive monitoring of radio and TV sources can generate significant amounts of ambient noise. For this reason, it is desirable to have a separate monitoring facility, some distance from the Command Center, so as not to generate a distraction to the business of the Command Center.12 The monitoring of media coverage can logically be assigned to the Public Information Officer and subordinates, who should probably be listening to the coverage in any case. If local TV news coverage is to be displayed in the Command Center itself, this should occur with the volume off, and closed captioning in place.

Two-way radio communications provide some additional depth of preparedness.13 Within the facility, they can provide a backup communications system for the telephone network, which is technologically independent of that network, eliminating or reducing the need for runners, in the event of a telephone network failure. In some locales, including both the cities of Ottawa and Toronto in Canada, private networks have been created, employing separate channels on the municipal EMS system’s Ultra High Frequency trunking radio networks. These networks provide major healthcare stakeholders, including hospitals, municipally operated long-term care facilities, and Public Health, with a robust backup method of maintaining communications and coordination between network members, even in the event of a regionwide telephone network failure. Other potential sources for this type of backup may include local amateur radio operators, who, if present in the community, may be very interested in providing this service. There are specific amateur radio organizations which deal with emergency communications, including the Amateur Radio Emergency Service in Canada and the United States,14 and RAYNET in the UK.15

When considering the use of two-way radio communications to support the Command Center, there are several factors which must be considered. Such systems will require an emergency power source, and this will, to some extent, dictate where such a facility can be located. Location will also be influenced by the fact that, like any other two-way radio, an antenna will be required. Such arrangements are generally made in advance, with the emergency power, antenna and antenna cabling preinstalled within a designated space, permitting the radio operator what amounts to a “plug and play” installation, when they arrive to assist the facility. It should also be noted that, as with passive radio monitoring, such systems do generate considerable levels of ambient noise. As a result, they should be located far enough away from the Command Center that their operating noise does not generate a distraction.

Information Technology and Network

The biggest single challenge to the development of a Command Center within a healthcare setting is potentially the acquisition and maintenance of the computers and peripherals which make up the information technology network.16 Such equipment is expensive, and the rate of technological evolution, and therefore, replacement, is very fast indeed. While it would be ideal for such equipment to be for dedicated use in the Command Center, the sheer cost of such a decision would be enormous, as would the ongoing maintenance requirements for equipment which was rarely used. As with the configuration of the Command Center itself, it is often best to ensure that as much of the network as possible is multiuse, thereby offsetting the acquisition and maintenance costs.

The first element of such a system is the individual computer itself. These should be standard throughout the network, and ideally, should be of the laptop type. Desktop systems are becoming increasingly obsolete and will rarely meet the actual day-to-day needs of the user, in any case. Tablets, on the other hand, while attractive from the perspective of both size and cost, do not yet have the capacity for day-to-day business use. A good laptop computer can do literally anything that a desktop can do with respect to daily business use, with the added advantage of being fully portable, and often, more favorably priced.

In many healthcare facilities, a program to replace desktop systems of executives and senior managers with laptops is probably already underway or has occurred. This measure should be encouraged by the Emergency Manager. As a general practice, it is often best to purchase the most expensive laptop model that can be afforded; the price of such units tends to drop as their time on the market increases, and therefore, the more expensive models typically will not require replacement as soon. This approach generally holds true for network peripherals, as well.

The model of computer selected should be standardized. There is sometimes a tendency among senior managers to attempt to use laptops as yet another “badge of office,” and the development of a competition to see who can acquire the most elaborate computer. This is an expensive and unnecessary approach and should be discouraged. Simply put, the more elaborate the computer, the more likely it is to require individualized support, and buying the best computers that can be afforded will almost always provide all of the features and services which are legitimately required.

In this manner, the entire system is composed of interchangeable components, and, from a hardware perspective, any computer can be replaced by any other. All computers should be equipped with Wi-Fi capability (increasingly becoming a standard feature), and each should have the ability to access the mobile telephone network in emergency circumstances, if required. All such devices come with their own chargers, but a spare battery may be required, if you ever anticipate extended usage times in no power environments.

If the use of services such as Skype are anticipated, the use of a headset is desirable, both to provide privacy and to eliminate the ambient noise for others in the Command Center. The ability to regularly back up data on the machine, by means of either a high-volume flash drive or a portable hard drive, is also recommended. All such items should fit together into a single, well-organized kit, often in its own carrying case, so that where the team member goes, so goes the computer, thereby ensuring availability in an emergency.

Virtually all organizations place some restrictions on corporately owned computers, on the types of software and the uses to which they can be put. This is completely reasonable and affects both security and appropriate usage. There is always a standard operating system (often Windows), along with a standardized suite of office tools, most often Microsoft Office. Other essential features for daily use include both an Internet browser of some type (there are several good ones) and some type of security software to protect the system from viruses and other types of malwares. On a more individual level, certain types of software or applications are sometimes banned from corporate networks. These often include social media sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and so on, and the ban is the result of a decision that the use of such media is not really an appropriate use of either a business computer, or the employee’s work time.

While such a configuration is fine for day-to-day use, the employee, as a Command Team member, may very well require access to resources during a crisis which are specifically banned for day-to-day usage. One example of this might be the need of the Public Information Officer to monitor what the public is saying about the emergency, or the hospital’s role in it, on social media, such as Twitter. They may even need to disseminate information to the public using this avenue. There are also other tools, such as hazardous materials reference tools as one example, which are of little use on a day-to-day basis but could prove essential during a crisis. It is entirely possible, working with the IT department, to create a system in which each computer has a standardized login, which provides access to the normal business tools, and a second, secure log-in, which logs the machine in at a different level, with on screen access to a more expanded set of tools required to manage the emergency. The employee does not even receive the log-in instructions until notified of the emergency, and so, the security of the corporate network is maintained. A conversation with senior staff can show how easy this step is to accomplish.

Computer peripherals are another consideration. Wherever possible, such devices should be wireless, and a backup device should be readily available for each primary device. Examples which may be useful in a Command Center setting include printers, flatbed scanners, fax machines, photocopiers,17 and projectors. The advent of a multipurpose device, in industry parlance an “all-in-one,” can greatly simplify this process. Such systems typically combine all of the above devices, except the projector, in a single unit, and the costs of such units is very low; often less than $100/unit at this writing. Such devices require appropriate cabling, paper, and printer ink cartridges, which are usually specific to the device itself. Each such device should have an identical replacement version, readily available nearby. It should be borne in mind that while such devices can be extremely useful in a Command Center setting, they are not intended for heavy commercial use, lacking the capacity for large-scale document production, for example. Access to larger commercial photocopiers and printers will continue to be required.

The development of a formal individual network for the Command Center will also be required. This provides a system which is independent of the main facility network and can be both more robust and more secure. Such systems can be hardwired, but this specifically eliminates the portability of the Command Center. More typically, such systems are wireless. The system will require one wireless router device with sufficient capacity to carry 10 computers and an appropriate range of peripheral devices. This router must be connected to both the emergency power supply and via Ethernet cabling to the Internet Service Provider’s network. While the Command Center itself is portable, the router is not; one router will be required for the primary Command Center site, and for each designated backup operating location. Advance work with the IT department will ensure that all of the required networking of devices can occur automatically (indeed, the entire system can and should be “plug and play”), and that the appropriate network security safeguards are in place.

Conclusion

An effective Command Center can greatly enhance the ability of any healthcare organization to effectively coordinate both service delivery and resources during any crisis. The size, type, location, and equipment of this type of resource will differ from one facility to the next, as all are driven by the specific needs of the facility. This is also true of the equipment and resources which should be made available within the Command Center. What is the Command Center intended to do? For whom? Under which circumstances? There is a vast difference between the requirements of a major general hospital attempting to coordinate the reception of victims from a mass-casualty incident, and a long-term care facility attempting to perform a controlled evacuation of 200 elderly residents because of a failure of heating systems in mid-winter. Just as the job changes, so do the requirements of the Command Center, and this connection between location, role, and expectations must be clearly understood by any Emergency Manager involved in its design.

It must also be understood that not all emergency situations are predictable, and that any good Command Center’s design must make it sufficiently flexible and adaptable to address a variety of circumstances, including those which may be unforeseen at the time that the Center is designed and built. Such facilities must be, to some degree, organic in their design; able to adapt and change with each new challenge in responding to emergencies. While the basic design will have specific parameters and expectations, changes in circumstances, roles, and technologies will occur, and these too will need to be incorporated into the design.

As recently as the 2000s, many hospitals and other facilities continued to rely on pagers for staff recall and overhead paging systems for internal communications. In this era of the nearly universal “smart phone” and ubiquitous tablet computers, offering such resources today would probably cause staff to question the knowledge and ability of the Emergency Manager! In truth, it is unlikely that any Emergency Manager operating in a healthcare facility at that time would have foreseen these developments, and yet, they MUST be accommodated. There is no doubt that similar changes in technology will continue to occur, and any Command Center design will require the ability to incorporate such changes as they occur.

Few specific resources exist which advise the Emergency Manager on the design of a Command Center, specifically for a healthcare facility. The vast majority of resources speak of an Emergency Operations Center (EOC), which is the increasingly common term for an emergency Command Center which serves a community, rather than a healthcare facility. Since it can be argued that any type of healthcare facility is, in fact, a specialized community, it is reasonable to draw from information on the design of community-based EOCs when considering the design of a Command Center for a healthcare facility. Indeed, such an approach can help to foster a basic ability to effectively integrate the facility’s response to the crisis with that of the local community. However, one must never lose sight of the primary business of the healthcare-based Command Center and meeting the needs of both clinicians and clinical managers will need to be considered.

Student Projects

Student Project #1

Select a healthcare facility and determine its Command-and-Control model and methodology. Select potential locations for a primary and a backup Command Center. Consider the potential technological options to support a Command Center in each location. Consider all options, including cost. Prepare a proposal for the assignment of your selected space for the purpose of a Command Center in the event of an emergency, explaining and justifying your choices and decisions. Ensure that the report is fully cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Student Project #2

Meet with Information Technology personnel in order to fully understand the facility’s existing computer network, its restrictions and its potentials. Conduct sufficient research to make yourself aware of currently available computer devices and technologies to support a Command Center operation in that facility. Consider all factors, including cost. Prepare a proposal for the acquisition and installation of a secondary computer network, aimed at supporting Command Center operations during and emergency, explaining and justifying your choices and decisions. Ensure that the report is fully cited and referenced, in order to demonstrate that the appropriate research has occurred.

Test Your Knowledge

Take your time. Read each question carefully and select the MOST CORRECT answer for each. The correct answers appear at the end of the section. If you score less than 80 percent (eight correct answers) you should re-read this chapter.

1. It has been said in emergency management circles, that the “currency” of disaster management is:

(a) Funding

(b) Staffing

(c) Information

(d) All of the above

2. In a healthcare facility, a Command Center’s basic design may be described as:

(a) Purpose-built

(b) Improvised

(c) Hybrid

(d) All of the above

3. A Command Center assembly system in which all essential equipment is stored in kit form on secured carts which are taken to the required operating location when needed is called a:

(a) “Pull” system

(b) “Push” system

(c) “Hybrid” system

(d) “Purpose-built” system

4. When considering the ergonomics of a potential Command Center space, the Emergency Manager should always consider:

(a) Lighting

(b) Heating/Air Exchange

(c) Ambient Noise

(d) All of the above

5. In healthcare settings, the most common physical layout used for Command Center designs is the:

(a) “Boardroom”

(b) “Marketplace”

(c) “Bull’s Eye”

(d) “Mission Control”

6. When planning to dynamically monitor news broadcasts as a Command Center function, it is essential that the placement of such equipment considers the problem of:

(a) Emergency power availability

(b) Generation of ambient noise

(c) Trip hazards due to cabling

(d) All of the above

7. No telephone operating in a Command Center should ever be equipped with voice mail because:

(a) Critical information can be lost/delayed

(b) Callers dislike voice mail

(c) Local legislation prohibits it

(d) All of the above

8. When considering the acquisition of computers and peripherals for the Command Center, it is best that such equipment should be:

(a) Dedicated to the Command Center

(b) Drawn from surplus equipment which is approaching obsolescence

(c) Multipurpose and in daily use

(d) Drawn from the equipment normally in the Business Office

9. When considering technologies for use in the Command Center, it is important to try to ensure:

(a) Multiple layers of redundancy, as a general principle

(b) Backup systems which are technologically independent of primaries

(c) The availability of older, more reliable technologies

(d) Both (a) and (b)

10. When creating a network, each potential operating site should be supported by a wireless router which:

(a) Is capable of supporting all of the devices in the room

(b) Is connected to an emergency power supply

(c) Is connected to the Internet Service Provider’s network

(d) All of the above

Answers

1. (c) 2. (d) 3. (b) 4. (d) 5. (a)

6. (b) 7. (a) 8. (c) 9. (d) 10. (d)

The author recommends the following exceptionally good titles as supplemental readings, which will help to enhance the student’s knowledge of those topics covered in this chapter:

Emergency Medical Services Authority, California. 2006. Hospital Incident Command System Guidebook, pp. 55, .pdf document, https://adacounty.id.gov/Portals/Accem/Doc/PDF/hicsguidebook.pdf (accessed March 28, 2015).

Emergency Operations Center Planning and Design. 2008. U.S. Defense Department .pdf Document, www.wbdg.org/ccb/DOD/UFC/ufc_4_141_04.pdf (accessed May 05, 2016).

Fagel, MJ. 2010. Principles of Emergency Management and Emergency Operations Centers (EOC) (Google eBook), CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, ISBN: 1439838526, 9781439838525

FCC/FEMA Tips for Communicating During an Emergency, FEMA/FCC webpage, http://www.fcc.gov/emergency-communications-tips (accessed March 27, 2015).

Joint Commission Resources. 2002. “Guide to Emergency Management Planning in Healthcare”, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, ISBN: 0866887555, 9780866887557

Rapp RR. 2011. Disaster Recovery Project Management: Bringing Order from Chaos, Purdue University Press, ISBN – 9781557535887