The Strength of ASEAN Economies

Overview

The group of ten countries assembled in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has a common ambition that is not merely consolidating their economies. Their goal is to become the center of gravity of the entire Asian region, in order to multiply channels of dialogue and diplomacy among the main international players, with the objective of promoting peace, stability, and security in the new geopolitical environment of rising regional powers. The East Asia Summits (EAS) are a good example of the regional architecture ASEAN is trying to build with its partners. The project of economic integration summarized below is conceived as a tool to achieve wider strategic goals than merely promoting economic growth and development.

It’s helpful to remind our readers of this wider perspective in the beginning of this chapter as we tapped into a trove of data and analysis from various international research institutions, including but not limited to the World Bank, the IMF, the OECD economic data forecasts, the Asian Development Bank, the ASEAN secretariat, the CIA Facebook 2014, Goldman Sachs, the Aseanist Times, the International Business Times, and the Economy Watch.

The ASEAN Economic Community

In January 2007, the ten Southeast Asian nations agreed to implement the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) with four objectives: (a) a single market and production base; (b) a highly competitive economic region; (c) a region of equitable economic development; and (d) a region integrated into the global economy.

The AEC is a highly ambitious effort to enhance ASEAN’s global competitiveness. Through the free flow of goods, services, and skilled labor, the project intends to establish an efficient single market and production base encompassing nearly 600 million people and $2 trillion in production. Business communities in the ASEAN hold that the regional economic integration would not disrupt their businesses, citing that it would even give even more opportunities rather than threats.

The ASEAN Business Advisory Council (ASEAN BAC) conducted a survey of 502 executives from companies of various sizes operating in the ASEAN region. The results of the survey, entitled 2013 ASEAN-BAC Survey on ASEAN Competitiveness,1 suggest that the ASEAN economic integration will pose a low or very low threat, 2.49 out of 5 (1 = very low to 5 = very high) to their organizations.

The survey was conducted in 2010, by ASEAN-BAC in collaboration with fellow scholars from Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. The integration of the regional politics and the economy within ASEAN, called ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), would take effect by the end of 2015, allowing free flow of economic activities and resources within the region. The survey showed that about 60 percent of the businesses in the region believed that AEC would provide high or very high opportunities for their organizations, as reflected by an average ratio of 3.59 out of 5 (1 = very low to 5 = very high).

The AEC areas of cooperation include human resources development and capacity building; recognition of professional qualifications; closer consultation on macroeconomic and financial policies; trade financing measures; enhanced infrastructure and communications connectivity; development of electronic transactions through e-ASEAN; integrating industries across the region to promote regional sourcing; and enhancing private sector involvement for the building of the AEC. In short, the AEC will transform ASEAN into a region with free movement of goods and services, investment, skilled labor, and freer flow of capital.

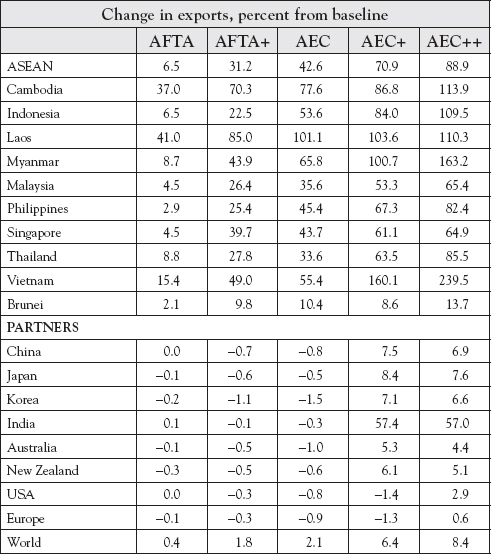

This agenda of economic convergence and interdependence has been viewed, since its outset, as one of the dimensions of the ASEAN Community, which member states decided to implement, to be effective by 2015. Economically speaking, with the implementation of the AEC, it is expected that ASEAN exports will expand by 42.6 percent, while imports will expand by 35.4 percent.

At the country level, the projections indicate a relatively low export increase of about 10.4–43.7 percent for the region’s most export-oriented economies such as Brunei, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore, and relatively high increases of 55.4–101.1 percent for the CLMV (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam) Asian sub-group economies. Table 3.1 lists the forecasted effects on international trade for the region by 2015.

The result will be a small increase in the region’s steady state trade surplus, attributed to the increased FDI inflows that the AEC is assumed to generate. Those inflows will give rise to steady-state outflows of investment income (profits), which need to be covered by a larger trade surplus. Following is a brief highlight of each of the ASEAN country members as of spring 2014.

Table 3.1 Effects on international trade in the ASEAN region (2015)*

*See ASEAN Charter, ASEAN, Community 2015, and ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint at ASEAN.org.

Brunei Darussalam

Brunei is a country with a small, wealthy economy that is a mixture of foreign and domestic entrepreneurship, government regulation, and welfare measures, and village tradition. The Sultanate of Brunei’s influence peaked between the 15th and 17th centuries when its control extended over coastal areas of northwest Borneo and the southern Philippines. Brunei subsequently entered a period of decline brought on by internal strife over royal succession, colonial expansion of European powers, and piracy. In 1888, Brunei became a British protectorate, and independence only was achieved in 1984. It is noteworthy that the same family has ruled Brunei for over six centuries.

The country is supported almost wholly by exports of crude oil and natural gas, with revenues from the petroleum sector accounting for 60 percent of GDP and more than 90 percent of exports. Brunei is the third-largest oil producer in Southeast Asia, averaging about 180,000 barrels per day. It is also the fourth-largest producer of liquefied natural gas in the world. The government, however, understands the risks of having too much of the country’s GDP relying on a single industry, and has demonstrated progress in its basic policy of diversifying the economy away from oil and gas.

Brunei’s policymakers also are concerned that steadily increased integration into the world economy will undermine internal social cohesion, though it has taken steps to become a more prominent player by participating as an active player in the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group.

According to Trading Economics,* Brunei’s personal income tax rate is 0 percent (2013), while inflation rates are also extremely low at 0.30 percent (August 2013). The per capita GDP in Brunei is among the highest in Asia, and substantial income from overseas investment supplements income from domestic production.

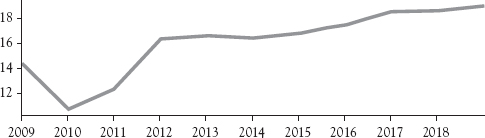

Figure 3.1 Brunei’s growing QDP

Source: Quandl

As Figure 3.1 shows, the country’s GDP in 2013 was $16.21 billion dollars, with an estimated GDP growth of $18.8 billion dollars by 2018.* The economy is projected to grow by an average of 2.4 percent from 2013 to 2017 as Southeast Asia recovers from a slowdown in 2011 and 2012, according to the OECD.2 For Bruneian citizens the government provides for all medical services, subsidizes food and housing, and provides complimentary education through the university level. The government owns a 2,262 square mile cattle farm in Australia, larger than Brunei itself, which supplies most of the country’s beef.† Eggs and chickens largely are produced locally, but most of Brunei’s other foods are imported.

Agriculture and fisheries sectors are among the government’s highest priorities in its efforts to diversify the economy, but while the country is best known for its substantial hydrocarbon reserves, the government also is starting to focus on green forms of energy, including solar. However, compared to some Southeast Asian neighbors, the Sultanate has set more modest goals and has been slower to develop alternatives to oil and gas.

The government actively encourages more FDI into the economy by offering new enterprises that meet certain criteria or a pioneer status, which exempts profits from income tax for up to five years, depending on the amount of capital invested. The normal corporate income tax rate is 30 percent, but as stated earlier, there is no personal income tax or capital gains tax. Hence, increased investment in research and development (R&D),3 combined with targeting niche markets, are two cornerstones of a strategy being rolled out by the government aimed at encouraging economic diversification. Japanese Mitsubishi has committed $2 million dollars investment in R&D, a figure that could expand multifold if results are satisfactory.

Brunei recorded a trade surplus of $719 million Brunei dollars ($578 million) in July of 2013. From 2005 until 2013, Brunei’s Balance of Trade averaged $1,307 million Brunei dollars ($1,051 million) reaching an alltime high of $2,971 million Brunei dollars ($2,390 million) in September of 2008. As an oil producer, Brunei has been able to run consistent trade surpluses despite having to import most of what it consumes. Oil and natural gas account for over 95 percent of Brunei’s exports, in addition to clothing.

Brunei mainly imports machinery and transport equipment, manufactured goods, food, fuels and lubricants, chemical products, and beverages and tobacco. Brunei’s main trading partners are Singapore, Malaysia, China, Japan, the United States, and Germany. Singapore, however, is the largest trading partner for imports, accounting for 25 percent of the country’s total imports in 2012. Japan and Malaysia are the second-largest suppliers. As in many other countries, Japanese products dominate local markets for motor vehicles, construction equipment, electronic goods, and household appliances. As of 2012, the United States was the third-largest supplier of imports to Brunei as of 2012.*

Cambodia

In 1995, the government transformed the country’s economic system from a planned economy to its present market-driven system.4 Hence, Cambodia currently follows an open market economy and has seen rapid economic progress in the last decade,5 where growth was estimated at seven percent while inflation dropped from 26 percent in 1994 to only six percent in 1995. Imports increased due to the influx of foreign aid, and exports, particularly from the country’s garment industry.

In October 2004, King Norodom Sihanouk abdicated the throne and his son, Prince Norodom Sihamoni, was selected to succeed him. Local elections were held in Cambodia in April 2007, with little of the pre-election violence that preceded prior elections. National elections in July 2008 were relatively peaceful, as were commune council elections in June 2012.

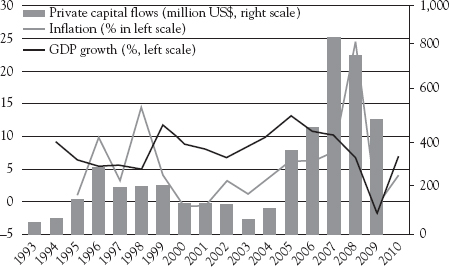

Nonetheless, since 2004, amidst all Cambodia’s political turmoil, garments, construction, agriculture, and tourism have driven Cambodia’s economic growth, as depicted in Figure 3.2.6 Agriculture has slowed but industry, while services expanded in 2013, maintaining economic growth at just above seven percent for the third consecutive year. Robust growth in services and expanding export industries drove economic growth of 7.2 percent in 2013. Services alone have remained the largest source of growth from the supply side, expanding by an estimated 8.4 percent in 2013. This stemmed largely from growth in wholesale and retail trading, real estate services, and tourism-related services. Bank credit to wholesale and retail trading increased by 24.5 percent to $2.5 billion and to real estate by 36.5 percent to $250.5 million. Tourist arrivals rose by 17.5 percent to 4.2 million. Political tensions and labor unrest suggest growth will ease in 2014 before picking up in 2015. Inflation, at modest rates last year, is seen edging higher in 2014. Spurring the development of small and medium-sized firms would help to sustain and diversify economic growth. GDP has climbed more than 6 percent per year between 2010 and 2012. In 2007, Cambodia’s GDP grew by an estimated 18.6 percent.

Figure 3.2 Cambodia’s economic performance 1993–2010

Source: CamproPost

In 2005, exploitable oil deposits were found beneath Cambodia’s territorial waters, representing a potential revenue stream for the government, if commercial extraction becomes feasible.7 Mining also is attracting some investor interest and the government has touted opportunities for mining bauxite, gold, iron and gems. The tourism industry has continued to grow rapidly with foreign arrivals exceeding two million per year since 2007 and reaching over 4.2 million visitors in 2013.* Cambodia, nevertheless, remains one of the poorest countries in Asia and long-term economic development remains a daunting challenge, due to endemic corruption, limited educational opportunities, high-income inequality, and poor job prospects.

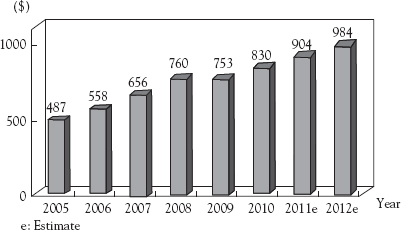

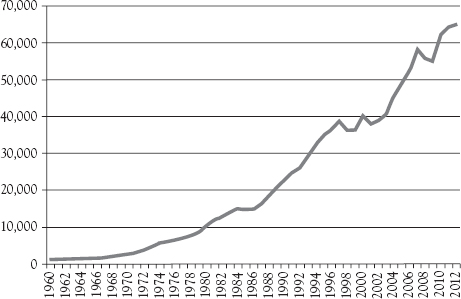

As depicted in Figure 3.3, and according to the Council for the Development of Cambodia8 (CDC), per capita GDP, although rapidly increasing since 1998 when the Riel greatly depreciated against the dollar, is still low compared with most neighboring countries in ASEAN. In 2013, per capita GDP reached $830 dollars, an increase of approximately 70 percent from $487 dollars in 2005.

Figure 3.3 Cambodia’s GDP per capita

Source: CDC

Cambodia’s two largest industries are textiles and tourism, while agricultural activities remain the main source of income for many Cambodians living in rural areas.9 The service sector is heavily concentrated on trading activities and catering-related services. About four million people live on less than $1.25 per day, and 37 percent of Cambodian children under the age of five suffer from chronic malnutrition. Over half of the population is under 25 years of age. This young population lacks education and productive skills. This is particularly true in the impoverished countryside, that also lacks basic infrastructure.

The major economic challenge for Cambodia over the next decade will be developing an economic environment in which the private sector can create enough jobs to handle Cambodia’s demographic imbalance. The Cambodian government is working with bilateral and multilateral donors, including the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, and IMF, to address the country’s many pressing needs, as more than 50 percent of the government budget is received by donor assistance. Presently, Cambodia’s main foreign policy focuses on establishing friendly borders with its neighbors, particularly Thailand and Vietnam, as well as integrating itself into the regional ASEAN and global WTO trading system.

Indonesia

Indonesia has the largest economy of the ASEAN. With the population exceeding 240 million, it is the fourth largest country in the world. Indonesia has a land area of around two million sq. km (736,000 sq miles) and a maritime area of 7.9 million sq. km. The Indonesian archipelago is the largest in the world and consists of over 16,000 islands, and stretches 5,000 km from east to west.

Despite the political turmoil of the late 1990s, Indonesia is politically stable today. Stability has not come easily but the democratic process prevailed with two consecutive mandates (to be concluded in 2014) of the first elected president, Dr Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

The reforms of 1999 ended the formal involvement of the armed forces in the government. Like other members of ASEAN, Indonesia has a market-based economy in which the government has traditionally played a major role. It has been a WTO member since 1995 and is now a proud member of the Group of Twenty Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, also known as G-20. Its economy is ranked as the 15th and 16th largest by the World Bank and the IMF, respectively.

Under President Suharto’s “New Era,” which extended from 1967 to 1997, the Indonesian economy grew in excess of seven percent until the Asian financial crisis, which was the lowest point of the economy and resulted in political instability. Since then, the rupiah has strengthened with the return of political and economic stability.

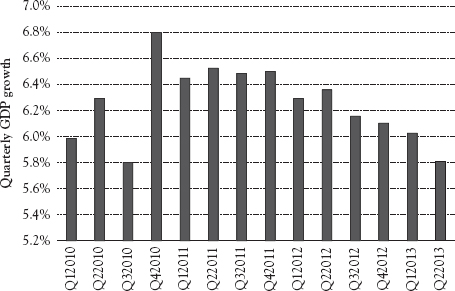

The banking sector and capital markets have been restructured. GDP growth, as depicted in Figure 3.4, rose steadily at four to six percent annually from 1998 to 2007. In 2008, there was a decline caused by a slump in exports and manufacturing and the global downturn that stunted its growth. During the second half of 2009, the growth rate did not gain new capital investment, which is attributed more to the lack of available credit and financing than any domestic economic issues. Indonesia recovered fairly quickly from the 2009 downturn and real GDP growth of six percent was reached in 2011. Subsequently, however, the country’s economy has slowed and 5.8 percent was the real GDP growth at the end of 2013.

Figure 3.4 Indonesia GDP growth has declined since Q4 2010

Source: Badan Pusat Statistik

Indonesia has been a net petroleum exporter and a member of OPEC, but left the organization in 2008 and has been importing oil since. This was mainly due to maturation of existing fields. In 2007, Indonesia ranked second (after Qatar) in world gas production. The oil and gas sector contributed over 31 percent to total government revenue in 2008 and maintains a positive trade balance. Indonesia had proven oil reserves of 3.99 billion or 0.29 percent of the world’s reserves. In 2008, its natural gas consumption was 33.8 billion cu m and proven natural reserves of 3 trillion cu m. Indonesia is also rich in minerals and has been exploring and extracting bauxite, silver, tin, copper, nickel, gold, and coal. A mining law passed in 2008 has reopened the coal industry to foreign investment. Indonesia exported 140 million tons of coal in 2008. The country ranks fifth among the world’s gold producers.

The government made economic advances under the first administration of President Yudhoyono (2004–2009), introducing significant reforms in the financial sector, including tax and customs reforms, the use of Treasury bills, and capital market development and supervision. During the global financial crisis, Indonesia outperformed its regional neighbors and joined China and India as the only G-20 members posting growth in 2009.

The government has promoted fiscally conservative policies, resulting in a debt-to-GDP ratio of less than 25 percent, a fiscal deficit below three percent, and historically low rates of inflation. Fitch and Moody upgraded Indonesia’s credit rating to investment grade in December 2011. Indonesia still struggles with poverty and unemployment, inadequate infrastructure, corruption, a complex regulatory environment, and unequal resource distribution among regions. In 2014, the government faces the ongoing challenge of improving Indonesia’s insufficient infrastructure to remove impediments to economic growth, labor unrest over wages, and reducing its fuel subsidy program in the face of high oil prices.

LAOS

In its foreign relations, Laos has slowly shifted from hostility to the West and a pro-Soviet stance to a more amenable and open policy with its neighbors in the region. Laos remains a one-party communist state and the political environment is stable. The LPR has been in power since 1975 and rules by decree.

Laos became a full-fledged member of ASEAN and joined the WTO in 2010. The country is a member of many international organizations such as United Nations, ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), Asian Development Bank (ADB), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Bank’s International Bank of Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), and IMF.

The Laos government started encouraging private enterprise in 1986 and now is transiting to a market economy but with continued governmental participation. Prices are generally determined by the market and import barriers have been eased and replaced with tariffs. The private sector is now allowed direct imports and farmers own land and sell their crops in the markets. From 1988 to 2009, the economy grew significantly, as shown in Figure 3.5, at an average six to eight percent annually. According to the World Bank,* growth is projected at 7.2 percent in 2014, with a moderate slowdown on the 8.1 percent recorded for 2013. Growth continues to be fueled by the resource sector, continued FDI-financed investment in hydropower, and accommodative macroeconomic policies.

Figure 3.5 Laos’s economic growth in GDP terms

Sources: Goldman Sachs; Forbes: Asian Development Bank

The resource sector is expected to provide a smaller direct contribution to growth in 2014. This is due to most major projects are under construction and not expected to commence operation this year. It is also due to expected lower gold production, which is likely to offset some of the gains expected from higher copper production. Despite being rich in natural resources the country remains underdeveloped, however, and nearly 70 percent of the population lives off subsistence agriculture, which contributes to roughly 30 percent of the GDP.

Industry is a growing sector (11 percent) and contributes 33 percent of its GDP. The main activity is the extraction industry with mining of tin, gold, and gypsum. Other industries include timber, electric power, agricultural processing, construction, garments, cement, and tourism. The service sectors account for nearly 37 percent of GDP and four new banks have opened in the last two years. Laos operates a managed exchange rate and the Lao kip has been strengthening.

A new commercial banking law was introduced in 2006. Lending to the private sector more than doubled in 2008 to the equivalent of 15 percent of GDP. The country’s first stock market launched in 2010 with 10 companies listed. A special economic zone is being set up in Savannakhet to promote foreign and domestic investment. Tourism has become a major revenue earner and has provided employment to many. In the 2012–2013, the fiscal deficit widened significantly, due to a combination of a large increase in public sector wages and benefits, and a decline in grants and mining revenues. The primary cause of the expanded deficit was due to an almost doubling of the total public expenditure on civil service wages and benefits. The 2013–2014 budget plan, however, indicates a slightly narrower fiscal deficit, but cuts in benefits will be offset by new recruitment as well as further increases in salaries paid to civil servants for two consecutive years. The government has discussed some revenue administration measures to help address the issue. In addition to revenue measures, there is a need for more prudent medium-term expenditure planning and execution by the government going forward.

Poverty has reduced substantially, from 46 percent in 1992 to 26 percent in 2009. Exports in 2009 including copper, gold, clothing, hydropower, wood and wood products, and coffee were sent mainly to Thailand (35 percent), Vietnam (16 percent) and China (9 percent). Imports were comprised mostly of machinery and equipment, vehicles, fuel, and consumer goods. The country is rich in hydropower generation, which provides almost 90 percent of electricity. There are no indigenous sources of oil and natural gas but PetroVietnam is exploring for oil and gas jointly with Laos. There are considerable untapped deposits of minerals and these are largely untapped. There are also ample sources of gemstones, especially high quality sapphires, agate, jade, opal, amber, amethyst, and pearls.

Numerous foreign mining companies are operating in Laos. In 2010, only China had mining projects here. The biggest source of income and investment continues to be hydropower and Laos hopes to become the “battery of Asia.” It plans to increase exports of hydroelectricity to 20,000 MW per year by 2020. Thailand is its main customer and the two countries already have an electricity purchase contract for 5,000 MW scheduled for 2015. Investment in hydropower projects has been rising with accumulated investment in 2000–2009 standing at $2.65 billion with Thailand, $2.24 billion with China and $2.11 billion with Vietnam. Laos was previously a major source of opium but major steps were taken to quell production, which is now at its lowest level since 1975.

Infrastructure development, streamlining business regulations and improving finance have been identified as the main priorities for the government. Construction roads and buildings for the Southeast Asian Games in December 2012 and for the celebration of the 450th anniversary of Vientiane as the country’s capital in 2010 have aided infrastructure development. A mini construction boom is being experienced around Vientiane. The manufacturing and tourism sectors are seen as the key sectors for private sector growth. The garment sector has created employment for over 20,000. There is still a vital a need to focus attention on ameliorating transportation and skill levels of workers.

Laos continues to remain dependent on external assistance to finance its public investment. In 2009, it launched an effort to increase tax collection and included value added tax (VAT), which has yet to be imposed. It also simplified investment procedures and expanded bank facilities for small farmers and entrepreneurs. Inflation is in check and has averaged five percent and the currency, the kip has been rising steadily against the U.S. dollar. In practice, the Lao economy is highly dollarized. Laos’ bill on imported oil remains large. The country’s international reserves have been strengthened through investments in hydropower and mining. The government maintains controls of the price of gasoline and diesel. The economy is expected to grow by around seven to eight percent annually.

Malaysia

Malaysia is one of ASEAN’s more successful economies and has been declared a middle-income country. It boats a free market economy and is fully integrated into the global economy. It has benefited from the advantage of being located on the Straits of Malacca, one of the most important shipping lanes in the world that connect the trade route between the East and the West.

Stemming from agriculture and mining based economy in the 1970s, it has been able to transform (itself) into a high-tech industrialized nation. The country has a well-developed infrastructure and a vast array of natural resources. Over 59 percent of Malaysia is forested. It is a major producer of tin, palm oil, rubber, petroleum, copper, iron ore, natural gas and bauxite. Services account for 48 percent GDP, industry accounts for 42 percent and agriculture 10 percent.

The manufacturing sector is productive in electronics, hard drives, and automobiles. The service sector has become increasingly important and this includes growth in real estate, transport, energy, telecommunications, distributive trade, hotel and tourism, financial services, information and computer services, and health services. Malaysia has a well-diversified economy.

The economy has been growing at six to eight percent and GDP, as depicted in Figure 3.6, touched $381 billion in 2009. There was a decline, however, during the Asian financial crisis when the government fixed the exchange rate of its currency, the ringgit, to the U.S. dollar in order to leverage the decline.

Since 2006, the Malaysian ringgit has operated as a managed float. The country went through another steep decline during the global economic stagnation of 2008–2009 but is slowly recovering. The government has injected the economy with a healthy stimulus package to jumpstart growth. Inflation, unemployment and poverty levels are low. The government has instituted banking and financial reforms. Local banks have been consolidated and fiscal liberalization is being introduced gradually. Greater incentives are being provided to invite foreign investment, especially in high-tech areas such as MSC Malaysia (MSC).10

Figure 3.6 Malaysia economic growth is significant

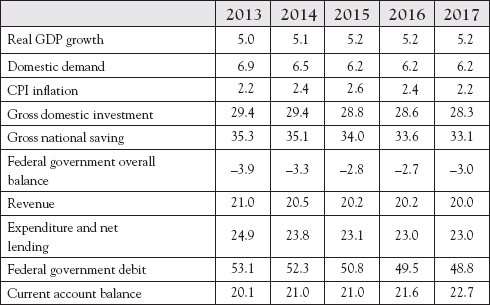

The MSC Malaysia, formerly known as the Multimedia Super Corridor, is a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Malaysia, which was officially inaugurated by the fourth Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad on February 12, 1996. The establishment of the MSC program was crucial to accelerate the objectives of Vision 2020 and to transform Malaysia into a modern state by the year 2020, with the adoption of a knowledge-based society framework. Figure 3.7 provides an insight into Malaysia’s growth outlook projections from 2013 through 2017 in various different sectors of the industry.

Exports remain the main driver of the economy, which totaled $226 billion in 2011. Oil and gas exports provide 40 percent of government revenue. Other top exports are electronic equipment, semiconductors, wood and wood products, palm oil, rubber, textiles, and chemicals. The present government is working to catapult the economy further up the value-added production chain and reduce dependency on exports. It is actively promoting investments in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing of automotive components, tourism, research and development, manpower development, and environment management. There are 13 free industrial zones (FIZ) and 12 free commercial zones (FCZ) where raw materials, products, and equipment may be imported with minimum customs formalities.

Figure 3.7 Malaysia’s growth outlook projections 2013-2017

Source: Tradingeconomics, IMF Global Outlook Report

A unique feature of the Malaysian economy is the New Economic Policy (NEP) launched in 1971 to reduce the socioeconomic disparity between the Malay majority and the Chinese minority. It was primarily an affirmative action system with the end goal of transferring 30 percent of the country’s wealth to the bumiputera (natives) Malays. The policy was implemented through programs that give preferential treatment to Malays through special rights in ownership of land and property, businesses, civil service jobs, education, politics, religion and language. In 1991, this policy was renamed the National Development Policy (NDP); the modified NDP still espouses the original goals, income inequality had been reduced, and the main objectives had not transpired. Much debate over this has ensued and many have felt that this policy created a small and wealthy Malay elite, as it reduced the Chinese and Indian minorities to second-class citizens. Hence, April 2009, the government removed some of the controversial ethnic Malay affirmative action requirements.

Overall, the government is improving from its already favorable investment climate by allowing 100 percent ownership in the manufacturing industry, liberalizing the financial sector and removing capital controls on overseas investments. Numerous infrastructure projects using state funding also have been initiated. Malaysia’s purchasing power remains among the highest in ASEAN.

Myanmar

Unlike most other ASEAN countries, Myanmar is not yet a fully free market economy. After it gained independence, as a reaction to years of colonization, the country adopted central planning, which resulted in a severe decline of the economy. From being one of the wealthiest export nations (rice, teak, mineral, and oil), it experienced severe inflation.

The subsequent military coup of 1962 saw further deterioration of the economy as Myanmar adopted the “Burmese Way of Socialism.” Industries were nationalized and the state owned all sectors of the economy, leaving only agriculture to the masses. By 1987, Myanmar made the UN’s list of least developed countries.

The country has suffered mismanagement of resources, low productivity, high inflation, large budget deficits and an overvalued currency, government control of financial institutions, poor infrastructure, and rampant corruption. In 1988, the government changed course and opened the economy to expansion of the private sector, encouraging foreign investment and participation in some sectors. Progress has been slow but increased trade with regional neighbors, fellow ASEAN nations, India and China has resulted. There exists a large informal economy, which includes trade in currency and commodities.

Myanmar has immense natural resources but the economy remains essentially agro-based. Over 50 percent of its GDP is derived from rice and other crops such as sesame, groundnuts and sugarcane, livestock and fisheries and forestry. Myanmar has one of the largest teak reserves in the world. It is also a net exporter of oil and natural gas and has substantial confirmed deposits. It has the 10th largest natural gas reserves in the world and the seventh largest in Asia. Precious stones are also abundant; 90 percent of the world’s rubies come from Myanmar. It also produces large amounts of sapphires, pearls, and jade, which are exported mainly across the border to Thailand. A large illicit cross-border trade exists, as Western sanctions do not allow major jewelry companies to import gems from Myanmar. Manufacturing remains a small component of the economy, just over 10 percent in 2008. Food processing, mining (copper, tin, tungsten, and gems), cement, fertilizer, oil and natural gas production and garments are its principal industries. The currency, the kyat, remains officially overvalued. A dual exchange rate exists and such inflation is a serious problem, which averaged seven percent in 2009, down from 22 percent in 2008 and 33 percent in 2007.

Myanmar has not received any loans from the World Bank since 1987 or any assistance from the IMF despite its membership to both organizations. It has been a member of the ADB since 1973 but has received no assistance in over 20 years. Its economic indicators, however, are positive, as depicted in Figure 3.8.

Liberalization of the economy is a work in progress. Production controls in agriculture have been removed. Privatization of state-owned enterprises is currently occurring. Over 100 state-owned companies were up for sale in 2010. The government reports that in 2009 it sold 260 state-owned buildings, factories and land plots. With the opening of the economy, foreign investments from China, South Korea, India, and ASEAN countries, including Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand have increased.

Figure 3.8 Myanmar’s economic indicators, 2008–2012

Source: ADB, 2013 Asian Development Outlook

Tourism has grown and infrastructure is being developed with participation from foreign investors. New industrial zones are being developed. Myanmar is an active participant and member of the Greater Mekong Sub-region Economic Cooperation Program (the GMS Program) together with Cambodia, China, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam as well as the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectorial Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) with Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. The Shwe Gas Project in the Bay of Bengal is a consortium of Kores Gas Corporation (KOGAS), which has a 51 percent stake; Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), GAIL (India); and the Myanmar-state oil company. The government has signed a contract to sell production to China, which is building a pipeline connecting a gas field to China.

Myanmar has the highest potential for hydropower in Southeast Asia and the government has set the goal of generating all electricity from hydropower by 2030. There are over 36 hydropower plants under construction. China has invested $200 million of the total $600 million cost and helped in the construction of the largest hydropower project in Ye Village. Another large project under construction is the Ta Sang project, which involves the building of a dam on the Salween River in the northeast of the country. This is a joint venture with a Thai company MDX Group. The project should be completed by 2022, with the electricity produced being to Thailand. In return, Myanmar will receive a certain percentage of free power.

Myanmar’s chief trading partners are Thailand, China, India, Singapore, Japan, Malaysia and Indonesia. It has border trade agreements with China, India, Bangladesh, Thailand and Laos. Several Memoranda of Understandings have been signed with these countries to expand bilateral trade. Myanmar remains isolated from much of the Western world and sanctions are still imposed by the United States, EU, Australia, and Canada. Trade with the United States and the EU were less than seven percent of total trade in 2007. Foreign currency reserves totaled $8.2 billion in 2013 mainly due to gas exports. GDP growth is estimated by the IMF to remain at around five percent for the next few years into 2015.

The Philippines

The Philippines was hit in the fall of 2013 by a natural disaster of tremendous consequences and the level of damage caused by it will most likely slow down its economy for a while, as the effort of its people and government takes priority in creating a robust economy and better conditions for development.

The history of the Philippines economy goes back to the end of World War II. Then, there was strong economic expansion and the Philippines became one of the Asia’s strongest economies. Sadly, the economy declined to become one of the poorest in the region due to years of economic mismanagement, political turmoil and misallocation of scarce resources. Oligopolies ruled a legacy of the U.S. colonial period, where farmland was concentrated in large estates.

As a policy, protectionism was used to prevent imports and restrictions were placed, preventing foreign ownership and other assets. This was exacerbated by rampant corruption and tax revenue remained low at only 15 percent of the GDP. There was underinvestment in infrastructure and disproportionate economic development, with the region around Manila producing 36 percent of the output with only 12 percent of the population. The result was economic stagflation during the Marcos era, severe recession in the mid-1980s, and political instability during the Aquino years (1986–1992).

Crumbling infrastructure, trade and investment barriers and a lack of competitiveness hampered long-term economic growth. More than half of GDP came from the service sector (53.5 percent); industry contributed 31.7 percent and agriculture, forestry and fishing accounted for the remaining 14.8 percent. Over 11 percent of the labor force was forced to go abroad to work and send remittances to their families. These remittances totaled $25.1 billion in 2013 and accounted for 8.4 percent of the GDP. A number of economic reforms were implemented during the Ramos presidency to help regain stability and the Philippine economy began to stabilize.

Macroeconomic stability has returned but long-term growth is doubtful due to poor infrastructure and education. GDP grew by 7.1 percent in 2007, the highest in 30 years. In 2008, GDP growth slowed to 3.7 percent. This was mainly the result of high inflation coupled with the worldwide downturn in export demand. Furthermore, the Philippines have suffered from a strong decrease in capital investment. Services grew by 3.1 percent in 2008 and 2.8 percent in 2009. Manufacturing had slightly better growth, despite drops in orders in the fourth quarter. Construction showed strong growth, while mining, metals, and agriculture displayed a sluggish performance.

The budget has shown a deficit every year since 1998, though trends in the last decade have been encouraging. The deficit is a direct result of overspending and poor collection of revenue. Attempts are being made to bring down debt ratios and raising new taxes has helped. Value added tax (VAT) was implemented in 2005 and raised from 10 percent to 12 percent and expanded its coverage. A law passed to increase revenue using a performance-based collection system. Though a deficit remains despite efforts to balance the budget for five consecutive years, deficit spending is considered necessary to cope with the economic crisis. A deficit of 0.9 percent of GDP was seen in 2008 and 3.2 percent in 2009.

Another source of revenue that needs improvement is the extractive industry. It is estimated that the Philippines possesses untapped mineral wealth of $840 billion. Mining has declined from 30 percent to only one percent of GDP but the country was a top mining producer in the 1970s and 1980s. In 2004, the Philippine Supreme Court ruled that foreign companies would be permitted to obtain mining and energy contracts with the Philippine government. Foreign companies now are permitted to own up to 100 percent equity and invest in large-scale exploration, development and utilization of minerals, oils and gas. GDP grew at around 1.1 percent in 2009 and 3.5 percent in 2010.

The government has taken steps to jumpstart the economy by introducing a $7 billion stimulus package. This money will be used to expand welfare, improve infrastructure and provide tax breaks for both private citizens and corporations. The country continues to have strong potential especially in the areas of mining, natural gas production, manufacturing, business process outsourcing (BPO) and tourism.

Inflation and unemployment remain major challenges. Infrastructure must be improved and greater reforms put in place to increase productivity and competitiveness. Tax revenues need to be increased further and reduction of poverty remains a top priority. We believe that trade liberalization to spur investment and increase competitiveness can help achieve greater growth. These reforms would lower cost of doing business and removing obstacles to growth.

Philippine GDP growth, as shown in Figure 3.9, which cooled from 7.6 percent in 2010 to 3.9 percent in 2011, expanded to 6.6 percent in 2012—meeting the government’s targeted six to seven percent growth range. The 2012 expansion partly reflected a rebound from depressed 2011 exports and public sector spending levels. The economy has weathered global economic and financial downturns better than its regional peers due to minimal exposure to troubled international securities, lower dependence on exports, relatively resilient domestic consumption, large remittances from four- to five-million overseas Filipino workers, and a rapidly expanding business process outsourcing industry. The current account balance had recorded consecutive surpluses since 2003; international reserves are at record highs; the banking system is stable; and the stock market was Asia’s second best performer in 2012.

Figure 3.9 Philippines economic growth 2010–2013

Source: National Statistical Coordination Board, the Wall Street Journal

Efforts to improve tax administration and expenditure management have helped ease the Philippines’ tight fiscal situation and reduce high debt levels. The Philippines received several credit rating upgrades on its sovereign debt in 2012, and has had little difficulty tapping domestic and international markets to finance its deficits. Achieving a higher growth path nevertheless remains a pressing challenge.

Economic growth in the Philippines averaged 4.5 percent during the Macapagal-Arroyo administration but poverty worsened during her term. Growth has accelerated under the Aquino government, but with limited progress thus far in improving the quality of jobs and bringing down unemployment, which hovers around seven percent. Underemployment is nearly 20 percent and more than 40 percent of the employed are estimated to be working in the informal economy sector. The Aquino administration has been working to boost the budgets for education, health, cash transfers to the poor, and other social spending programs, and is relying on the private sector to help fund major infrastructure projects under its Public-Private Partnership program. Long-term challenges include reforming governance and the judicial system, building infrastructure, and improving regulatory predictability.

Singapore

Singapore has a highly developed and successful free-market economy. It enjoys a remarkably open and corruption-free environment, stable prices, and a per capita GDP higher than that of most developed countries. The economy depends heavily on exports, particularly in consumer electronics, information technology products, pharmaceuticals, and on a growing financial services sector. Real GDP growth averaged 8.6 percent between 2004 and 2007.

The economy contracted one percent in 2009, as shown in Figure 3.10, as a result of the global financial crisis, but rebounded 14.8 percent in 2010, on the strength of renewed exports, before slowing to 4.9 percent in 2011 and 2.1 percent in 2012. This was largely a result of soft demand for exports during the second European recession. Over the longer term, the government hopes to establish a new growth path that focuses on raising productivity, which has sunk to a compounded annual growth rate of just 1.8 percent in the last decade. Singapore has attracted major investments in pharmaceuticals and medical technology production and will continue efforts to establish itself as Southeast Asia’s financial and high-tech hub.

Figure 3.10 Singapore’s annual per capita GDP

Source: Singapore Department of Statistics

Singapore is poised to undertake a plethora of reforms in order to be one of the hubs of the global economy. Political pressure is forcing Singapore to rethink the liberal immigration policy that was once part of its strategy to become a global city. Although creative foreign workers have contributed greatly to economic development, at the same time its liberal immigration policy creates many non-negligible issues, and ones in which society will need to cope. The government is tightening entry conditions for foreign workers, while at the same time encouraging foreign entrepreneurs. It is investing heavily in development of human capital of indigenous workers, and encouraging businesses to upgrade their technology and production methods.

As part of that investment effort, the government has lent strong backing to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). They account for over half of total enterprise value and employ nearly 70 percent of the workforce. Their rise, though, has been largely driven by government policy, which has funded them and boosted domestic market growth. This begs the question as to how sustainable this state’s SME policy is in the long term. Research and Development (R&D) is considered an important component of Singapore’s policy of productivity-driven economic growth. In the last two years since 2013, the government has brought local SMEs into R&D with cash incentives to help them develop.

Combined public and private R&D expenditure have put Singapore among the most R&D-intensive countries. Nevertheless, it lags behind in private R&D spending. As a small city-state with no natural resources, Singapore has been careful in managing its human capital, regarding such management as an important source of competitiveness and strength for the economy. Over the years, public expenditure on education has consistently been the second highest, after defense, in the government’s annual fiscal budget. In the 2012 budget, for example, expenditure on education claimed a 17.9 percent share, compared with 20.8 percent for defense. Such emphasis on education has helped contribute to Singapore’s stronger record in human capital development than other countries in the region. Over the past decade, a major force shaping the human capital landscape in Singapore has been the increased presence of foreign workers.

As part of the overall strategy to transform Singapore into a global city, the government aggressively liberalized the foreign worker and immigration policy.* From 2000 to 2011, the number of non-residents rose from 754,500 to 1,394,400, representing a jump from 18.7 percent to 26.9 percent of the total population. In contrast, the share of Singapore citizens (excluding permanent residents and non-residents) in the population steadily declined from 74.1 percent in 2000 to 62.8 percent in 2011.† The aggressive pursuit of the global city vision has transformed not only the physical look of the city-state, but also its business environment and production coupled with these changes.

The composition of the labor force has also been significantly altered both in terms of the local-foreign mix and the mix between workers in old and new industries. While the open-door labor policy brought in a large number of highly skilled, high wage foreign workers, it has also led to a huge influx of low-skilled, low-wage foreign workers. Whereas the former could potentially expand the economy’s range of skill sets and raise its productivity level, the latter could substantially offset such positive effects. Indeed, with the readily available of low-wage foreign workers, firms in Singapore might not find many incentives to upgrade their technologies and production structures, or to invest in training or upgrading workers’ skills sets.

Thailand

Recent political unrest in Bangkok and other cities, due to deep divisions in Thai society, has created uncertainty for the future of this vibrant economy. With a well-developed infrastructure, a free-enterprise economy, generally pro-investment policies, and strong export industries, Thailand has achieved steady growth largely due to industrial and agriculture exports—mostly electronics, agricultural commodities and processed foods.

Bangkok is trying to maintain growth by encouraging domestic consumption and public investment. Unemployment, at less than one percent of the labor force, stands at one of the lowest levels in the world, which puts upward pressure on wages in some industries. Thailand also attracts nearly 2.5 million migrant workers from neighboring countries. Bangkok is implementing a nation-wide 300 baht per day minimum wage policy and deploying new tax reforms designed to lower rates on middle-income earners.

The Thai economy has both internal and external economic shocks in recent years. The global economic crisis severely cut Thailand’s exports, with most sectors experiencing double-digit drops. In 2009, the economy contracted 2.3 percent. However, in 2010, Thailand’s economy expanded 7.8 percent, its fastest pace since 1995, as exports rebounded. In late 2011, historic flooding in the industrial areas north of Bangkok, crippled the manufacturing sector and interrupted growth. Industry has recovered since the second quarter of 2012 and GDP expanded 5.8 percent in 2012. The government has invested in flood mitigation projects to prevent similar economic damage.

Vietnam

Vietnam is one of the success stories of Asia’s revival, a country marked by tragedy and despair because of the conflict that desecrated the former Indochina and ended three decades ago. The Vietnamese quickly have learned the lessons from the changing international environment. Even before the dissolution of the former Soviet Union, this densely populated developing country has transitioned from the rigidities of a centrally planned economy since 1986. Vietnamese authorities have reaffirmed their commitment to economic modernization in recent years.

Vietnam’s economic growth quickened in the second quarter of 2014 as the outlook for exports improved after the dong was devalued for the first time in a year. Despite the global recession, Vietnam’s economy continuers to charge ahead, with GDP rising at 5.25 percent in the second quarter from a year earlier, according to data released by the General Statistics Office in Hanoi.* That compares with a revised 5.09 percent pace in the three months through March. The economy expanded 5.18 percent in the first half from a year earlier, compared with a median estimate of 5.2 percent in a Bloomberg News survey of 8 economists.

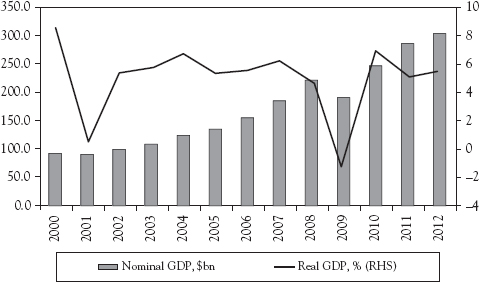

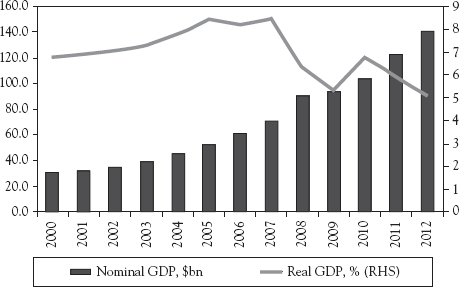

Agriculture’s share of economic output has continued to shrink from about 25 percent in 2000 to less than 22 percent in 2012, while industry’s share increased from 36 percent to nearly 41 percent in the same period. State-owned enterprises account for 40 percent of the GDP. Notwithstanding, in terms of nominal GDP, Vietnam’s economy has grown consistently since 2000, as shown in Figure 3.11. Likewise, poverty has declined significantly, and Vietnam is working to create jobs to meet the challenge of a labor force that is growing by more than one million people every year.

Unfortunately, what is also depicted in Figure 3.11, the global recession hurt Vietnam’s export-oriented economy, with real GDP in 2009–2012 growing less than the seven percent per annum average achieved during the previous decade. In 2012, however, exports increased by more than 12 percent, year-on-year; several administrative actions brought the trade deficit back into balance. Between 2008 and 2011, Vietnam’s managed currency, the dong, was devalued in excess of 20 percent, but its value remained stable in 2012.

Figure 3.11 In terms of nominal GDP, Vietnam’s economy has grown consistently since 2000

Foreign direct investment inflows fell 4.5 percent to $10.5 billion in 2012. Foreign donors have pledged $6.5 billion in new development assistance for 2013. Hanoi has vacillated between promoting growth and emphasizing macroeconomic stability in recent years. In February 2011, the government shifted away from policies aimed at achieving a high rate of economic growth, which had fueled inflation, to those aimed at stabilizing the economy, through tighter monetary and fiscal control.

In early 2012 Vietnam unveiled a broad, three-pillar economic reform program, proposing the restructuring of public investment, state-owned enterprises, and the banking sector. Vietnam’s economy continues to face challenges from an undercapitalized banking sector. Non-performing loans weigh heavily on banks and businesses. In September 2012, the official bad debt ratio climbed to 8.8 percent, though some financial analysts believe it could be as high as 15 percent.

![]()

* TE country indicators, http://www.tradingeconomics.com/brunei/inflation-cpi, (last accessed on 11/02/2013).

* According to Quandl country indicator, http://www.quandl.com/economics/ brunei-all-economic-indicators.

† According to the U.S. Department of State report on Brunei, http://www.state. gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2700.htm, (last accessed on 09/12/2013).

* TE country indicators. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/brunei/imports, (last accessed on 11/02/2013).

* Ministry of Tourism, of Cambodia (2014) Tourism Statistics Report 2013, http://www.tourismcambodia.org/images/mot/statistic_reports/tourism_statistics_annual_report_2013.pdf

* http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lao/publication/lao-pdr-economic-monitor-january-2014-managing-risks-for-macroeconomic-stability, (last accessed on 06/19/2014).

* OECD; ASEAN Secretariat: CIA Faxback (2014).

† Department of Statistics Singapore (2011).

* http://www.gso.gov.vn/default_en.aspx?tabid=491, (last accessed on 06/21/2014).