Can MENA’s Rise be Powered by BRICS?

Overview of the MENA Region

This chapter provides an overview of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region followed by a review of recent trade and investment relations between MENA and BRICS countries. It also reviews and discusses challenges and opportunities for economic development arising from the complementarities and interactions between countries form both blocs.

The people of the MENA region have long played an integral, if somewhat volatile, role in the history of human civilization. MENA is one of the cradles of civilization and of urban culture. Three of the world’s major religions originated in this region, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Universities existed in this region long before they did in Europe. In today’s world, MENA’s politics, religion, and economics have been inextricably tied in ways that affect the world economy. The region’s vast petroleum supply, which accounts for two-thirds of the world’s known oil reserves, is a major reason for the world’s interest, especially from advanced economies. MENA’s influence, however, extends beyond its rich oil fields. It occupies a strategically important geographic position between Asia, Africa, and Europe. It has often been caught in a tug-of-war of land and influence that affects the entire world.

According to the World Bank1 the diversity of countries in the MENA region, as depicted in Figure 4.1, is great, particularly in terms of population and resources, and can be segmented in three groups:

•Oil exporters–these countries are rich in resources and have large shares of foreign residents. It is comprised of the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) and Libya.

Figure 4.1 Map of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region

•Developing countries–these are countries rich in resources with large native populations and include Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen.

•Oil importing countries–these are countries poor in resources that are small producers or importers of oil and gas, and include Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Jordan, and Lebanon.

In terms of population, the MENA region has quadrupled from 1950 to 2007, and is expected to increase by 60 percent until 2050. MENA’s rapid population growth exacerbates the challenges that this region of the world faces as it enters the third millennium. For hundreds of years, the population of MENA hovered around 30 million, but reached 60 million early in the 20th century. Only in the second half of the 20th century the population growth in the region gained momentum. The total population increased from 100 million in 1950 to 380 million in 2000, an extra 280 million people in only 50 years.

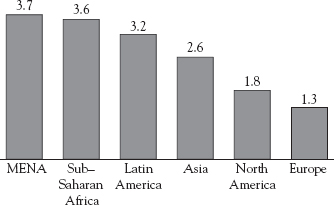

As depicted in Figure 4.2, during this period the population of the MENA region increased 3.7 times, more than any other major world region over the past century. MENA’s annual population growth reached a peak of 3 percent around 1980, while the growth rate for world as a whole reached its peak of two percent annually more than a decade earlier.* Improvements in human survival, particularly during the second half of the 20th century, led to rapid population growth in MENA. The introduction of modern medical services and public health interventions, such as antibiotics, immunization, and sanitation, caused death rates to drop rapidly in the developing world after 1950, while the decline in birth rates lagged behind, resulting in high rates of natural increase (the surplus of births over deaths).2

Figure 4.2 Ratio of population size in 2000 to population size in 1950, by major world regions

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2001)

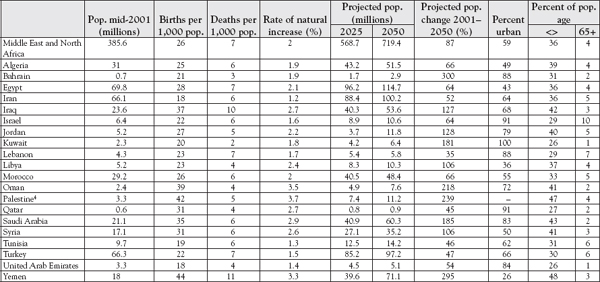

On average, fertility in MENA declined from seven children per woman (1960) to 3.6 children (2001). The total fertility rate, the average number of births per woman, is less than three in Bahrain, Iran, Lebanon, Tunisia, and Turkey, and is more than five in Iraq, Oman, Palestinian Territory, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen. Even though the decline in fertility rates is expected to continue in the MENA region, the population will continue to grow rapidly for several decades. In a number of countries, each generation of young people enters childbearing years in greater numbers than the previous generation, so as a whole they will produce a larger number of births. The population of the region is increasing at two percent per year, the second highest rate in the world after sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly seven million people are added each year. As indicated in Figure 4.3, the population growth is most significant in the Western Asian countries encompassing Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinian Territory, Syria, and Turkey.

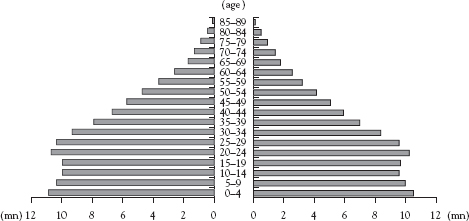

MENA’s demographics of a young population pose both strengths and weaknesses as shown in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.3 Population size and growth of MENA region

Source: Carl Haub and Diana Cornelius, 2001 World Population Data Sheet; UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children 2001, Table 7.

Figure 4.4 MENA’s population pyramid, 287 million, 2010

When it comes to economic performance of MENA in terms of GDP, the region has essentially two distinct groups of countries: the Gulf countries that until 2011 have had a GDP per capita above $10,000 dollars, and the North Africa and other Middle East countries which have not exceeded $5,000 dollars per capita, as depicted in Figure 4.5. This variation in development levels indicates the superior performance of the resource-rich labor importing countries. However, as discussed later, the reasons for these outcomes are not solely related to resources but also with the historical and institutional development of the MENA’s countries before, during, and post colonial times.3

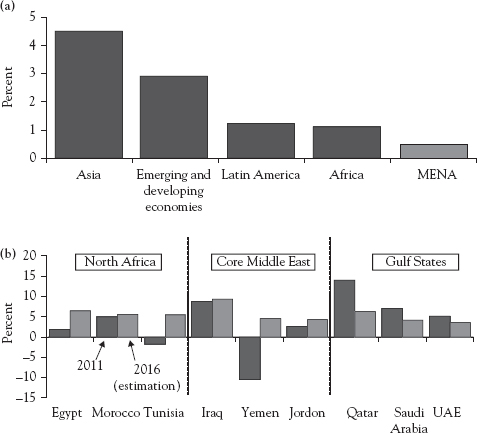

According to IMF Survey Magazine,4 the healthy growth rates of the region’s oil exporters—Algeria, Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen—are projected to moderate from an average of 5.7 percent in 2012 to 3.2 percent in 2013. This is mainly due to a scaling back of increases in oil production amid modest global demand. The average real GDP per capita from 1980 to 2010, however, lagged significantly behind other regions of the world, as depicted in Figure 4.6. Nevertheless, despite the recent turmoil in the MENA region, GDP is expected to be over five percent by 2016.

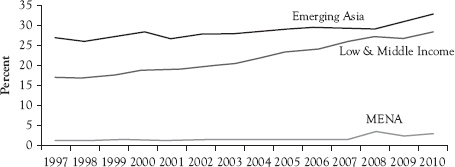

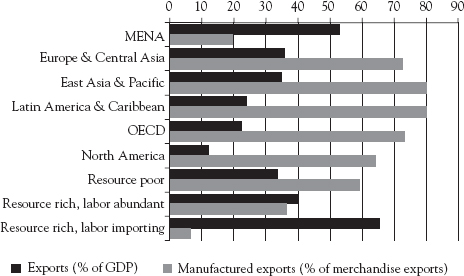

By contrast, the region’s oil importers—Afghanistan, Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Sudan, and Tunisia—face a difficult external environment. On average, this group of countries is projected to post moderate growth of three percent in 2013. For the Arab countries in transition, continued political uncertainty is also preventing growth. Hence, to assess to what extent the MENA region has benefited from globalization it is worthwhile to examine exports and FDI flows. In regards to exports we find that the percentage of non-oil exports in MENA region is significantly lower than in emerging countries in Asia and other low and middle income countries, as depicted in Figure 4.7, suggesting that the region is not as globally integrated as others.

Figure 4.5 GDP per capita in North Africa, Core Middle East, and Qulf Countries5

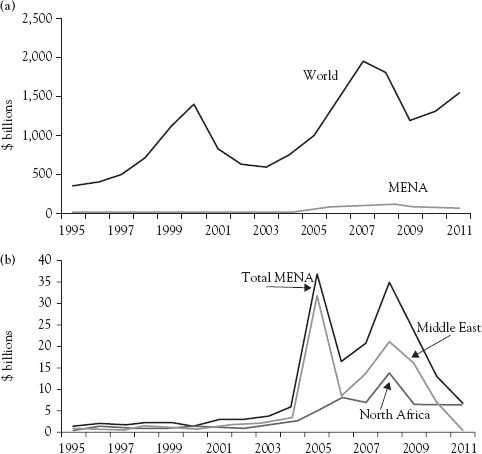

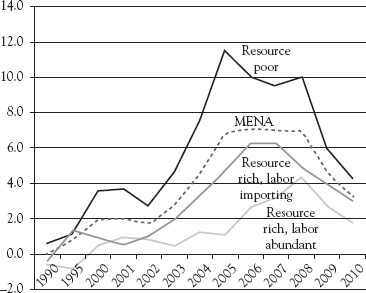

Second, in terms of FDI inflows to the region, we find that in the period from 1995 to 2011 the FDI inflow to the MENA region was stagnant and lower than the world average. This was true again after the 2008 world crisis has declined, as depicted in Figure 4.8.

Figure 4.6 Real GDP per capita and expected QDP growth in selected MENA countries

Source: IMF

Figure 4.7 Non-fuel exports (percentage of world non-oil exports)

With high fiscal deficits and reduced international reserve buffers, many oil importers have no time to waste embarking on difficult policy choices—considerable fiscal consolidation—implemented in a growth-friendly and socially balanced way—and greater exchange rate flexibility. This should help maintain macroeconomic stability, instill confidence, preserve competitiveness, and mobilize external financing, thus putting in place important preconditions for a healthy economic recovery.*

Figure 4.8 FDI flows to the MENA region relative to the world and after 2008 world crisis

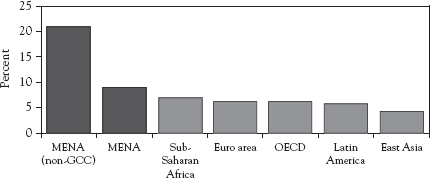

Finally, it is important to understand the role of tourism as source of revenue in the MENA region. With its world-class combination of cultural and natural attractions, the MENA region, according to the World Bank,6 has long held a powerful allure for tourists. It has made tourism an important source of revenue and growth. In 2011, the industry contributed an estimated $107.3 billion, representing 4.5 percent of the region’s GDP, and accounted for 4.5 million jobs, almost seven percent of total employment. Figure 4.9 illustrates the percentage of tourism revenues for 2010 between the non-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) MENA countries, the MENA and other regions of the world.

Figure 4.9 International tourism receipts (percent total exports), 2010

Long-term Issues of the MENA Countries

According to O’Sullivan and Galvez7 at the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Arab Spring has accentuated problems in the MENA region that already existed for some time. These issues include a high level of unemployment, which is more acute among youth, pervasive corruption combined with lack of transparency and accountability, a bloated public sector that hinders the development of private enterprises, limited levels of entrepreneurship, and inflation in resource-poor countries.* Therefore, the MENA bloc could substantially benefit from other blocs, particularly the BRICS.

To understand how MENA could be further connected with the BRICS countries it is important that we take a closer examination of each of these internal issues.

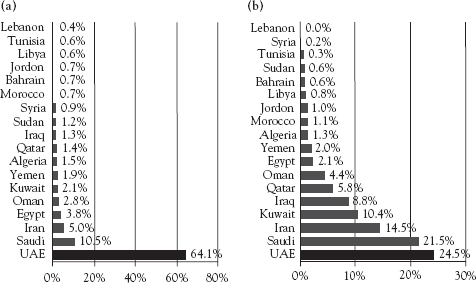

•Unemployment—Data from WEF† suggests that in the MENA region the Palestinian Authority has the highest unemployment rate (above 20 percent) followed by Yemen, Tunisia, Jordan and Algeria (above 10 percent), whereas the GCC countries have the lowest rates, as depicted in Figure 4.10A. However, unemployment is particularly serious among young people (15–24 years old), as depicted in Figure 4.10B.

Figure 4.10 Unemployment rates in MENA

Source: O’Sullivan, Rey, and Galvez, 2011, based on World Bank data

As O’Sullivan point out, every year there are about 2.8 million young workers who enter the labor market but they find it increasingly more difficult to procure viable employment. Moreover, few countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Morocco, and UAE have a large percentage of unemployed who are educated due to a persistent mismatch between job market requirements and skills acquired at a university. Lastly, the gender gap in unemployment, meaning the very low participation of women in the labor force, indicates another missed opportunity for the optimization of resources for economic development.

•Corruption, lack of transparency, and poor accountability—The Arab Spring was motivated in large part for these three issues, the solution to which will invariably mean a change to the political structures in most of the MENA countries. According to Transparency International* only two MENA countries perform well in the corruption index, Qatar at 7.7, and UAE at 6.3†, with the average score for the MENA region at 3.1. The reform processes in some MENA countries, such as Egypt and Tunisia, however, promise to change the institutional frameworks, with transparency likely to increase.

•Bloated public sector distorts labor markets—Employment in the public sector ranges from 22 percent in Tunisia to about 33–35 percent in Syria, Jordan, and Egypt, but if we exclude the agricultural sector then the public sector employment reaches 42 percent in Jordan and 70 percent in Egypt. The public sector provides higher salaries, job security, and social status that the private sector cannot match, thus reducing the pool of qualified candidates for the private sector. Moreover, during periods of crisis many of the MENA’s governments have responded by increasing salaries and creating more jobs to appease discontent and increase consumption. This has short and long term consequences. In the short term it offers relief and an economy with a stimulus; in the long term it has a negative impact on the public budget’s sustainability, particularly in resource-poor countries, and inhibits the innovation and entrepreneurship in the private sector.

•Low entrepreneurship levels—The World Bank Group Entrepreneurship Survey‡ suggests that in high-income countries there are about four companies created per 1000 working people, whereas in the MENA the average is only 0.63 new firms. In the BRICS region the rates are 2.17 new firms in Brazil, 4.3 in Russia, 0.12 in India and no available data for China or South Africa. Based on the OECD research O’Sullivan8 mentioned, low business creation in MENA region is due to the high barriers for small firms doing business (e.g. corruption, licenses, rigid laws, taxes, unfair competition), lower social status attached to entrepreneurial activity as compared with public sector, and low participation of women in the workforce.

•High inflation in resource-poor MENA countries—The average inflation in the MENA countries from 1999 to 2005 was about three percent but it increased to 6.5 percent in the following five years (2006–2010). While the resource-rich countries found compensatory measures to cope with negative effects of inflation, the resource-poor countries did not. The reason for high inflation in resource-poor countries is mainly due to a spike in import prices of food and fuel. O’Sullivan et al.* note that given the rising incomes of middle class in most emerging economies and the instability in MENA countries, the inflation is likely to continue here.

In addition to the factors described, the economic growth of the MENA region is also due to other economic and structural factors, namely low levels of competitiveness in manufacturing sectors, lack of export-market diversification, and low intra-regional integration.† These issues present opportunities for the BRIC countries, which can provide assistance and complementarities for furthering economic development in the MENA region. Thus, it is important that we review the recent economic developments in the MENA region.

The Economic Impact of the Arab Spring

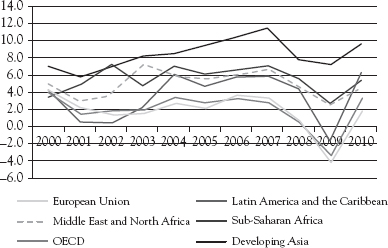

When comparing the economic performance of the MENA region to other regions, we find that MENA countries have been performing relatively well, on par with Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, but below emerging Asian countries, yet above OECD and EU countries as depicted in Figure 4.11.

Figure 4.11 GDP growth by region, percent change, constant prices

Source: O’Sullivan et al., 2011, based on IMF and OECD data

The impact of the Arab Spring has had varying effects in the MENA region depending on the extent of the turmoil and economic fundamentals. First, the political and social instability caused an immediate negative effect in the countries affected by the turmoil. However, as O’Sullivan et al.* noted, the countries with stronger economic fundamentals, such as Egypt and Tunisia, are expected to recover faster if a successful political transition and economic reform continue to be implemented. In contrast countries such as Morocco and Jordan did not experience significant tensions but their respective economies are more exposed to negative spillovers and likely to recover at a slower pace. Second, the turmoil caused a significant rise in oil prices, which indirectly benefited the resource-rich countries. Moreover, the weak economic performance of OECD countries is likely to have a negative impact in MENA countries as trade and investment originated at OECD is likely to remain slow.

Trade Diversification and Intra-Regional Trade are Low

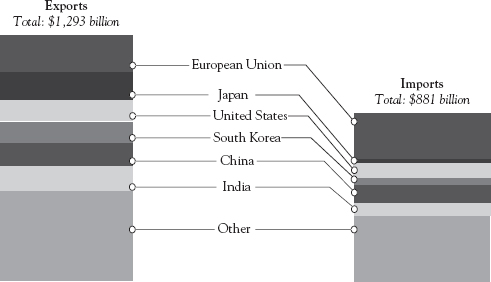

In 2009, the trade of the MENA region was $932 billion in exports and $742 billion in imports, however it was not diversified. The major export category in MENA countries is oil, representing about 62 percent of total exports, while the imports are manufactured goods, 54 percent of the total imports, as depicted in Figure 4.12.

Figure 4.12 MENA’s exports and imports of goods and services with the world, by commodity or type of service, 2009

Source: Akhtar, Bolle, and Nelson, 2013

Regarding MENA’s partners, as of 2011 the most significant was the EU followed by China and the United States, as depicted in Figure 4.13. Note however that as a single country China is the most influential trading partner of MENA.

MENA has failed, however, to increase its global market share in part because the region’s exports flow mainly to Europe and are concentrated in traditional products. Europe has been the main destination for MENA exports, reflecting proximity and long-standing linkages. Since the 1970s, the region’s exports to Europe have accounted for close to 60 percent of total exports, while exports to Asia Pacific and Latin America, respectively, have accounted for 15 percent and one percent of total exports. Until the mid-1970s, the focus on European markets linked the region to an engine of global growth. But, more recently, this focus has implied that MENA has not been benefiting from the high growth rates achieved in emerging Asian and Latin American powerhouses, including Brazil, India, and China.

Figure 4.13 MENA’s major trading partners, 2011

Source: Akhtar, Bolle, and Nelson, 2013.

Notwithstanding, exports from the MENA region have increased significantly in the past years. When considering exports as a percentage of GDP, MENA’s exports have increased from 35 percent in 1990, to 39.2 percent in 2000, up to 53 percent in 2009.* However, as O’Sullivan and his colleagues noted, a closer analysis reveals two noteworthy trends. First, the increase of exports is mainly due to increased value of oil exports from resource-rich countries, as depicted in Figure 4.14.

And second that the current account balance of resource-poor countries is worsening, as depicted in Figure 4.15. Looking ahead, there are unknowns as to the timing of Europe’s recovery. Moreover, there is a broad consensus that, over the medium term, growth in Europe will lag behind that of emerging Asia and Latin America. As such, it is even more important to redirect MENA’s exports to these dynamic regions of the global economy, such as the BRICS and ASEAN, and to allow MENA to link more closely to the new growth engines and thus provide a foundation for high and sustained growth.

Figure 4.14 Exports as a share of GDP are high in MENA, but manufactured exports are comparatively low

Figure 4.15 Current account balance as percent of GDP

MENA exports, according to IMF’s Masood Ahmed9 have primarily concentrated on consumer goods, and less so in high value-added, high technology, intermediate and capital goods, which have seen the most growth in recent years. Consumer and primary goods currently account for 64 percent of total exports in this region, compared to 41 percent for Asian countries, 57 percent for Latin American countries and 66 percent for African countries. Capital goods, on the other hand, account for only six percent of MENA exports, similar to the seven percent in low-income countries, while they account for 37 percent of Asian exports and 11 percent of Latin American exports. These export patterns hold back MENA’s potential for trade and, indeed, MENA countries trade less with the rest of the world than could be expected. MENA’s total exports in 2009 amounted to only 28 percent of GDP, compared to 30 percent for Asia Pacific, 56 percent when excluding the three largest economies, Japan, India, and China, given that large economies typically have lower export shares.

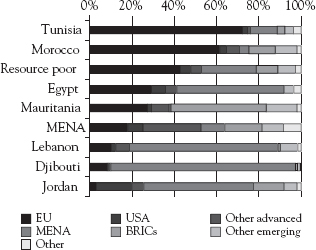

When examining the export markets for MENA countries we find that the resource-poor countries mostly export to the EU, and that intra-regional trade among MENA countries has increased but compared with EU and other markets it is still modest, as shown in Figure 4.16. Moreover, in terms of trade with the BRICS countries, the exports have increased but are not yet significant, which suggests that there may be opportunities for further exports into the BRICS markets.

A country’s export volumes are driven partly by characteristics such as proximity to markets, tariff rates, the establishment of free trade agreements or cultural linkages with trading partners. However, these characteristics do not explain MENA’s low export-to-GDP ratio–quite the opposite. Looking at the exports of the each MENA country, as depicted in Figure 4.17, we find other interesting patterns. First, Tunisia and Morocco have a large percentage of exports to EU. Second, Mauritania’s exports are concentrated in the BRIC, particularly China, where it exports 40 percent of iron ore. Third, Lebanon, Djibouti, and Jordan send most of their exports to MENA countries. Lastly, Egypt is the country with the most balanced export markets.

Figure 4.16 Resource-poor countries’ main export market is the EU, and BRIC markets is still modest

Figure 4.17 Resource-poor countries’ main export market is the EU, but to varying degrees

Trade variations, as noted by O’Sullivan et al.,10 are due in part to varying supply and demand chains. In terms of demand, China imports oil, gas and natural resources, and EU manufactured goods.

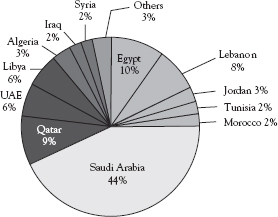

Foreign Direct Investment at MENA

As of 2010, foreign direct investment (FDI) in MENA countries amounted to $64.5 billion, and nearly two thirds of which derives from resource-rich countries, namely in Saudi Arabia, which attracted over 44 percent of MENA’s total FDI.* The resource-poor countries attracted about 25 percent of the FDI, as shown in Figure 4.18, with Egypt and Lebanon as the main recipients. The remaining FDI was channeled to resource-rich countries characterized by political instability. Overall the data suggests that investments are attracted by opportunities in resource-rich countries provided they offer a relatively stable context.

Figure 4.18 FDI inflows to the MENA region, 2010

Figure 4.19 FDI as a share of GDP in the MENA region, 2010

Interestingly, when considering FDI as a share of GDP (Figure 4.19), we find that resource-poor countries are performing better than other countries in the region, which points to increasing opportunities for investment. The FDI inflow to resource-poor countries jumped from 0.6 percent of GDP in 1990 to 12 percent in the mid-2000s. Due to the financial crisis of 2008–2009, there was a decline, but the relative performance of the resource-rich countries remained.

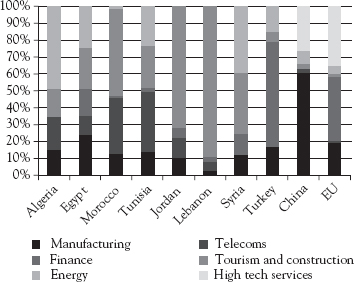

Figure 4.20 FDI by economic sector, cumulative 2000-2007, percent of GDP

When looking at non-energy sectors that have attracted FDI to resource-poor countries we find that it is attributed mostly to service industries, namely telecommunications, tourism and construction, while the manufacturing industries have received a low level of FDI, as depicted in Figure 4.20.

Integration of BRICS with MENA

The economic integration of MENA’s region with Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa has increased recently with varying levels of integration. In general this trend brings visible benefits, but it is not without challenges. Benefits include increasing revenues through exports, higher quality consumer welfare by lowering prices on consumption and lowering manufacturing input costs. Challenges consist mainly of increased competition for domestic companies in MENA, particularly, as World Bank’s Pigato11 noted, for unskilled and resource-intensive manufacturing and food items in labor abundant countries.

The prospect of furthering integration seems to combine a mix of economic optimist with political caution. A report by Ernst & Young and Oxford Economics12 predicts that MENA’s trade flows will grow fastest with Russia, India, and China over the period 2011–2020. Researchers of this study expect global trade to grow at about 9.4 percent (p.a.), but MENA’s trade flows will grow even faster, specifically trade with Russia will grow at 14.4 percent p.a., with India at 13.5 percent p.a. and with China at 12.5 percent p.a. On the other hand, annual trade with the United States, EU, and Japan will grow at slower pace, respectively: 8.4 percent, 7.7 percent, and 7.3 percent.

Brazil and MENA’s integration is based on a growing economic partnership catalyzed in 2003 when President Lula da Silva proposed the creation of the Summit South America and Arab Countries.13 Since then the volume of trade between Brazil and MENA countries increased at a rate of 13 percent per annum, from $4.9 billion in 2002 to $26 billion in 2012.

Yet all this economic optimism may need to be tempered by political risks to MENA countries. A cursory glance of this issue, namely, the United States changing direction toward the Middle East will be reviewed later on in this chapter. The next section examines the prospect of further economic integration of each BRIC country with MENA region.

Brazil and MENA

In 2010, Brazil’s balance of trade with Arab countries was positive. The export volume was $12.5 billion and imports were merely $6.9 billion only. Exports were concentrated mostly on meat, sugar, minerals, and cereals; respectively about 25 percent, 23 percent, 17 percent, and 13 percent of the total exports. The imports were essentially focused in oil resources (84 percent). Inward and outward FDI of Brazil and MENA countries are of little consequence. UAE investors in the hotel sector in Brazil did the most significant investment.*

According to Marcelo Nabih Sallum,14 President of the Chamber of Commerce Brazil-Arab Countries, the exponential growth in trade between Brazil and the Arab countries is due mainly to the large potential market of MENA countries. Mr Sallum mentioned that there are opportunities to improve bilateral relations not only in trade but also in tourism, financial services and investments, construction, and health.

Russia and MENA

The cooperation between Russia and the MENA countries benefits from the Soviet legacy. During the 1950 to 1980s the Soviet Union assisted Arab nations in building several infrastructure projects, but that cooperation ceased and only started to pick up again in the 1990s and 2000s particularly after official visits of the Russian presidents to Algeria in 2006 and 2010.15 According to Senkovich, Russia aims to reestablish cooperation with the traditional partner countries of Algeria, Lybia, Syria, and Iraq, as well as enter in the markets of the GCC monarchies’ markets.

Trade between Russia and MENA was about $14 billion in 2011 and was largely dominated by the Russian exports (90 percent of trade) of precious metals and stones, metal products and machines, transport equipment, coal, and arms, as well as oil and petroleum products which are exported to non-oil producing countries in MENA.

In terms of investment, Arab nations are interested in Russian’s technology expertise in higher value industries such as oil and gas production, petrochemicals, remote sensing, water demineralization, nuclear power, space, and Information Technology (IT).* On the flip side, Russia is interested in attracting investments from Arab resource-rich countries, however, Senkovich argues, Arabs perceive Russia as a high-risk market.† Yet, he adds, both inward and outward investments between Russia and MENA seem to be moving too slowly allegedly due to competition from Western countries and China.

India and MENA

The influence of India and China in the MENA region is growing rapidly and is expected to become critical for the development of the three regions. Two recent studies have examined the recent economic integration of MENA region with India and with China (Al Masah Capital Management Limited, 2010; Pigato 2009).

The MENA countries have been major trading partners in meeting India’s energy needs, particularly Saudi Arabia (the largest oil supplier to India), as well India’s export markets, namely UAE (the largest external MENA market for India). In 2009–2010, total trade between India and MENA countries was $116.9 billion but two thirds of this ($83.9 billion) was trade only with the GCC, as depicted in Figure 4.21.

Figure 4.21 India’s exports and imports to and from MENA countries, percent share, 2009–2010

Source: Department of Commerce, India

According to Al Masah Capital,16 the MENA region can benefit further from India’s expertise in services, namely IT related industries, science and technology, and education. To boost economic ties in the MENA region India has been in talks with GCC countries to establish a free trade agreement and is now pushing for a quick conclusion of the negotiation process.

The investments between India and MENA are essentially anchored in Saudi Arabia. Since mid-2000 more than 100 Indian companies have established joint ventures in Saudi Arabia and half of these have reciprocated and established joint ventures in India.* Incorporating Al Masah Capital’s report in 2006–2007, more than 82 new licenses were granted to Indian companies in order to establish business in Saudi Arabia. These are expected to be valued at roughly $467 billion in Saudi Arabia, mostly in service industries.

Regarding MENA’s FDI in India, the GCC countries are the major investors in India. For example, Saudi investment in India from 1991 to 2004, was $228 billion, mostly from the industrial sector, (e.g. chemicals, machinery, cement, metallurgy, paper manufacture), as well as in the computer software sector. In just the second and third quarters of 2010, UAE invested $1,792 billion in India and an additional $326.6 billion in Oman.*

In terms of future cooperation, Al Masah Capital points out that 4.5 million Indians already live and work in the Gulf region in a range of jobs from unskilled to professional and highly skilled labors; meaning the human capital from India can be a suitable complement to MENA’s countries that lack qualified workers. It is suggested that MENA’s oil resources combined with India’s technology and human capital may provide the opportunity to create new ventures and cooperation, particularly in four sectors: real estate development, energy, petrochemicals, and transport infrastructure.

To conclude, it is worth noting that despite political risks in the MENA region, India is expected to become its main trading partner by 2013–2015 (HSBC Bank, 2013). The rich MENA countries, particularly Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt are likely to be the main drivers of India’s exports.

China and MENA

China and India’s spectacular economic rise over the last two decades has accelerated their trade with Africa, Latin America, and MENA. Their demands for oil, gas, and other natural resources have been forging new relationships with MENA countries based not only on energy but also on trade, investment, and political ties. Indeed, Dubai has become the new Silk Road—the intersection where people, capital, and ideas meet—and Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Mumbai, Riyadh, and Cairo are the new centers.

The future may well bring new opportunities and faster growth to MENA countries, but the challenges are formidable. For MENA oil-producing countries, faster growth in China and India will increase revenues from oil and the difficult choices associated with their management. For the labor abundant, non-oil producing countries, competition with China and India will spotlight the need for policy measures to increase productivity. This may require broader institutional changes seen in China and India—and thus may take time. But the horizon for creating much needed employment is shorter, suggesting the importance of a pragmatic reform agenda that can accelerate productivity, trade, and investment in the region.

Trade between China and MENA has increased significantly in recent years. In 2009, China became the largest exporter to Middle East countries with a two-way trade value of $107 billion.* Saudi Arabia and UAE are the two major trading partners of China in the MENA region, with the former being the major exporter to China and the latter the main importer from China, as depicted in Figure 4.22.

Bilateral trade between Saudi Arabia and China rose to $41.8 billion in 2008 and is estimated to reach $60 billion by 2015 based mostly on oil exports to China.† Trade between China and UAE has been centered mostly on exports of low-cost Chinese goods into UAE and base materials and related materials from UAE to China.

A report focusing on the link between MENA and China (Arabia Monitor, 2012) indicates that there are growing trading synergies between the two regions not only in the traditional oil and resources sectors but also in agriculture and industry. With the decline of exports to Europe MENA’s food exporters are expected to capitalize on China’s increasing food demand. The same research indicates that Chinese industrial conglomerates (particularly in the automobile industry) also are expected to invest directly in MENA countries in order to gain faster access to the markets in the region. While China’s FDI in the region represents just 1.5 percent of its total investment outflow, in terms of MENA’s FDI it represents 3.5 percent of the total inflow. Thus the effects of Chinese integration are likely to create significant impact.

Figure 4.22 China’s exports to MENA (left) and China’s import from MENA (right), percent share, Jan–Oct 2008

Source: Ministry of Foriegn Trade, People’s Republic of China

South Africa and MENA

For centuries, trade has been integral to most countries that constitute the MENA region. As momentum in global business shifts toward greater intra-emerging markets, or “south-south” trade and investment, the MENA economies are well positioned to benefit. But how far and fast the MENA region integrate into these new economic relationships will depend on how executives from other emerging markets view it, and how such perspectives may differ from those of their peers in the developed world. Hence, it is important to understand a few historical facts regarding the MENA region to better understand its impact on global trade.

Historical Perspectives

At the beginning of the 1990s, just before the end of Apartheid, South Africa had diplomatic relations with no country in the Middle East except Israel, another country with limited ties to nations in its own region until the end of the Cold War.* Before Israel’s recognition as a nation in 1948, the same year that Apartheid became official government policy, South Africa had established diplomatic relations with Egypt. Formal relations with Lebanon and Iran came later. Egypt had become a prominent support of African liberation organizations following the establishment of the Arab nationalist regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1956 that lasted until the early 1960s.

According to Michael Bishku, on an essay published at the Middle East Policy Council Journal,17 in Lebanon’s situation, trading relations continued until the mid-1970s, at which time they were formally severed due to pressure from the Arab League states. As for Iran, the Islamic Revolution brought a definitive end to relations with the Apartheid government. Naturally, Jewish and Lebanese ethnic populations in South Africa are factored in, with regard to Israel and Lebanon. As for Egypt, it was the most important African country aside from South Africa and one of only a few independent African states until the late 1950s, the others being Ethiopia and Liberia.

In addition, South Africans were militarily involved in Egypt during WWII as part of British Commonwealth forces fighting the Germans. During that war, Reza Shah Pahlavi, ruler of Iran from the 1920s, was sent into exile on Mauritius—but later moved to South Africa, where he died in 1944—by the British, who accused him of German sympathies; his son and successor, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, who faced a Soviet threat to his rule following WWII, viewed South Africa as a bulwark against the spread of communism and, like Israel, an important market for Iranian oil. The shah was a rival of Nasser, who looked toward the Soviet Union for military support during the mid-1950s, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev began supporting Third World liberation movements. Diplomatic relations between South Africa and the Soviet Union were severed during his time.

Perspectives on Investments Inflow and Trade

According to a survey conducted by Lewis, Sen, and Tabary for the Economist Intelligence Unit18 in July 2011, there are striking differences in the way respondents from different regions of the world perceive the MENA region as a place of doing business. Of course, there are similarities too. According to the survey, most multinational companies plan to expand significantly in the region, especially in the Gulf States. And most cite concerns over political risk, bureaucratic red tape and, in particular, a perceived lack of transparency in the region. However, there are major differences in the way that executives from different regions view the prospects for democracy in the Middle East and the likely implications for their own businesses. The culture and norms of respondents’ home markets also seem to influence their attitudes toward such factors such as volatility in the business environment, corruption and diversity.

Lewis, Sen, and Tabary* argue that the Middle East region will benefit strongly from accelerating “south-south” business, particularly with increasing trade between emerging markets. While executives from all regions expect the Middle East to feature more prominently in their global business plans over the next five years, it is among Latin American firms, followed by those from Asia-Pacific and North America, where this trend is most pronounced.

Businesses’ views on the potential impact of the Arab Spring on trade and investment are divided. While investors broadly welcome the outbreak of pro-democracy movements across the Middle East, the upheavals of the Arab Spring create short-term political risk that can dent business confidence. Almost one-half of all respondents of the Economist Intelligence Unit survey report† agree that the current unrest in the region is likely to have an adverse effect on their business in the near future.

The UAE is the most favored destination in the Middle East for business expansions and trade, with expansion plans centered on the wealthy Gulf States, probably reflecting the beneficial impact of high oil prices on the economic outlook for these countries. The Gulf States also are favored due to the perception that political risk is lower than in other countries in the region. The UAE is by far the most popular investment and trading location, cited by 63 percent of respondents overall. Latin American executives also showed strong interest in Egypt and Morocco. Emerging-market firms are more likely to focus activities on less saturated markets and sectors.

Latin American firms are less worried about the impact of political turmoil on business in the Middle East than any other region in the world. According to Lewis, Sen, and Tabary survey* 55 percent of total respondents from Latin America say that the political upheaval seen recently in the region (2013) is unlikely to affect business adversely in the medium to long term, compared with 43 percent of respondents from both North America and Asia-Pacific. This could reflect the fact that many Latin American countries have come through their own transitions from authoritarian or military rule to democracy in the past 25 years. Nevertheless, a majority of investors, unsure how to handle rapid change, say that if forced to choose, they would prefer stability over democracy.

Corruption is less of a concern for emerging-market firms than it is for businesses from developed markets. Corruption is a relatively minor concern for emerging-market investors in the Middle East, especially among Asian and Latin American companies. However, for European and North American firms, corruption is cited as having a major impact on operations, possibly reflecting tighter anti-corruption legislation, such as the Foreign Corrupt Practice Act (FCPA), in their home markets.

Cultural factors also present major concerns for emerging-market businesses. A significant minority of the Economist’s† survey respondents from all regions adheres to the view that businesses and workers may face discrimination on the basis of gender, race or nationality in the Middle East. Attitudes toward women and ethnic minorities significantly deter economic development of the region. Almost half of Latin American businesses believe that the business culture of the Middle East is more suitable for corporations from other emerging markets than for corporations from advanced economies. Some emerging-market investors also expressed concern that their goods, services or employees are not treated on par with those from Western countries.‡

The burgeoning youth population that is demanding political change in the Middle East is also valued as an economic resource. Demographics are seen at least as important as oil and gas resources when it comes to driving opportunities for business in the Middle East. Nearly 50 percent of all Economist’s survey* respondents expect business opportunities to emerge from the growth of a new middle class, while 41 percent cite the growing youth population as a source of opportunity. Respondents from Europe are particularly likely to value the region’s demographics, probably reflecting concerns about slowing population growth, aging populations and market saturation in their home markets. Fifty-two percent of European respondents cite the growth of young population as a source of opportunity, compared with just 33 percent who cite commodities.

The gradual shift toward emerging markets reflects policy decisions by Middle Eastern governments, including the region’s major oil exporters, who are well aware that their future top customers are located in Asia, and not in the G-7 group. Indeed, when the current Saudi ruler, King Abdullah bin Abdel-Aziz Al Saud, came to the throne, his first overseas trip was to Beijing, not to the United States or UK. For a brief period in 2009, China imported more oil from Saudi Arabia than the United States—something that may become a permanent reality in the near future assuming Chinese oil consumption grows and the United States continues its policy of reducing its reliance on Middle East oil. Moreover, some of the region’s authoritarian rulers have been particularly attracted to the so-called China model: focusing on economic development but not on political reform. In contrast to the United States or Europe, China does not seek commitments on human rights in order to sign trade deals. While China’s approach to trade may appeal to authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, this year’s Arab Spring of popular uprisings in favor of greater democracy is likely to force governments in the region to reconsider their foreign and trade policies.

South Africa has expressed keen interest in expanding its trade relations with the MENA bloc. In late November 2013, the South African Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) lead a business delegation to the Middle East, one of South Africa’s important trade zones, with the objective of enhancing trade and investment relations in that region. According to the news outlet allAfrica,19 DTI’s outward trading mission to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait was aimed at building the commitments made by the DTI to expose South African companies to the Middle East market and to deepen bilateral trade and investment relations between these countries.

DTI’s Minister, Rob Davies, argues that the Middle East is an important trade zone for South Africa, holding great potential for South Africa as an export market, and serving as a potential source of FDI, as he sees the Middle East as one of the world’s fastest growing markets for manufactured products and services.* Indeed, Saudi Arabia is South Africa’s largest trading partner and second largest export destination in the Gulf region. In 2012 alone, total bilateral trade between the two countries amounted to R61.7 billion rand. Kuwait is one of South Africa’s major trading partners, and is the sixth largest export destination in the Middle East, with a total bilateral trade between the two countries amounted to R246 million rand in 2012.

Turkey also has a role to play in South African DTI’s trade mission, as its Deputy Minister, Elizabeth Thabethe, has been focusing on an outward selling and investment mission to that country. According to Thabethe both South Africa and Turkey are featured in one another’s top 40 lists of imports and export trade partners. The two countries are regional powerhouses in their respective regions. South Africa’s exports to Turkey have been steadily increasing to an extent that the trade deficit in favor of Turkey has been significantly reduced.

Currently, South Africa conducts trade with MENA in various industrial sectors including agro-processing, manufacturing machinery and equipment, and capital equipment. Turkey has targeted the following sectors for the mission: energy, mining, infrastructure, information and communication technology, capital equipment and engineering, and textiles.

In concluding this section, it is worth mentioning that, according to Cashin, Mohaddes and Raissi,20 the MENA countries are more sensitive to macroeconomic developments in China than to shocks in the EU or the U.S. According to McKinsey Consulting,21 trade flows between China and the GCC are expected to rise to between $350 and $500 billion dollars by the year 2020. This supports the idea that the interconnectedness between China and MENA region will be a significant force shaping the world economic environment.

Rising Together?

In March 2013, the fifth BRICS summit was held in Durban, South Africa. The heads of these governments acknowledged the need to operationalize the recommendations received by the think tanks of their countries. There is a need to accelerate from talk into action. One idea shared during the meetings was the possibility of the BRICS countries to create a new development bank, one mandated to assist developing nations (south-south development). Deen22 mentioned that one area of intervention of this bank could be to assist some MENA countries, specifically Egypt, who is seen as having significant influence in the Arab world.*

Certainly, companies around the globe recognize the long-term economic potential of the Arab world. Trade between Middle East countries and others, particularly those from emerging markets, has been increasing for years, and is likely to grow further as part of a broader trend of greater economic exchange between non-OECD countries. Political authoritarianism and instability have forced many investors to think twice about their plans in the short term, although many emerging-market firms appear less worried about volatile operating conditions. A significant minority of executives in all regions (except the Middle East itself) believes that local attitudes toward women and ethnic minorities would hold back the region’s economic development. Nevertheless, the current upheavals of the Arab Spring are giving hope to investors from all regions that, despite obvious short-term difficulties inherent in political transition, a more transparent business environment will emerge eventually.

MENA Countries Attract Less FDI Than Other Emerging Markets

While concerns about corruption, infrastructure and political uncertainty will remain worrisome in the medium term, the opportunities deriving from a young and growing population are all too evident, and our survey shows that investors from all regions are planning major expansion into the MENA region. Firms from other emerging markets are increasingly seeking opportunities outside the oil and gas industry, in the less-developed sectors and countries across the region. Latin American firms are leveraging their expertise in fostering innovation in agriculture. Others are finding a niche in providing goods and services by competing on price or quality.

For companies from industrialized countries and emerging markets alike, significant challenges remain in doing business and attracting FDI in the Middle East. But the region is changing in visible ways, as made clear from the Arab Spring, and in ways that are more imperceptible, as in the recalibration of policies and attitudes toward business. The region today represents opportunities that businesses around the world are keen to grasp. Given the trends in global trade and investment, it is more than likely that the attractiveness of the opportunities will outweigh the risks over time.

According to Daniele and Marani,23 however, the underperformance of MENA countries to attract FDI is due to several major factors, namely: the small size of local markets and lack of real economic integration; changes in international competition for FDI; slow institutional and trade reforms; and political and macroeconomic instability. However, to overcome these obstacles MENA countries need to improve their governance systems that, according to various indicators, display poor performance, as depicted in Figure 4.23.

The MENA region encompasses countries with diverse wealth concentrations and resource levels, widely divergent economic structures and trajectories ranging from wealthy Gulf monarchies to poor countries such as Yemen.24 As Cammett* pointed out the development of MENA countries is shaped not only by economic and institutional factors but also by the culture and history of these countries. While most of the explanations regarding development in MENA countries are valid there is still no clear understanding of what are the most important factors, and more importantly of how political and economic institutions in MENA region will reproduce and change in the future. The future presents opportunities for both the MENA and BRIC countries to cooperate further but not without uncertainties and risks.

Figure 4.23 MENA governance indicators

Source: Daniele and Marani, 2006

Opportunities in the MENA Region

Growth and trade in the MENA region is constrained by several factors. On the one hand, growth is hindered by difficulties in access to finance, labor skill disparities and shortages, and electricity constraints.25 On the other hand, underperformance in MENA’s trade is constrained by logistics and transport limitations and inefficiencies in custom clearance processes.26 Despite such huge challenges, O’Sullivan and colleagues27 noted that there are some clear opportunities in the MENA region to consider, and which the BRIC countries should be aware of when developing relations with MENA. The opportunities are as follows:

•The young population as a market and labor force. As the average age in the MENA countries is just 25 years, well below other emerging regions, there will soon be a larger labor force and consequently a rise in consumption levels. However, for this opportunity to materialize governments need to develop institutional frameworks that promote essential social needs, namely education, employment, health, and housing. Renewable energies, including solar sources in all MENA countries, hydropower (Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and Syria) and wind (along the Red Sea and Morocco’s Atlantic coast). The International Energy Agency forecasts that by 2035 the use of renewables for electricity generation could reach 33 percent and FDI reach $400 billion provided that adequate policies and institutions are implemented.

•The tourism sector already represents a large industry in some MENA countries and provides significant sources of employment and exports. MENA countries have traditionally targeted tourists from European and Gulf markets, however, with increased purchasing power of people in emerging countries MENA can expand into new tourism markets.

•Agro-industries in MENA countries with sufficient water resources also offer significant growth potential. Such countries include Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, Egypt, and Syria. The opportunities will exist in both domestic and emerging markets essentially due to demographic trends and economic growth. Internally, the demographic trend in the MENA region and its subsequent expected consumption (as described earlier), there will be higher demand for food products. The same phenomenon can already be seen in other emerging countries, such as China. One particular benefit of the agro-industries is that it will open up business opportunities and create employment in related industries upstream (farming) and downstream (handling, packaging, processing, transporting, and marketing).

•And of course there will be a plethora of opportunities in the energy sector. The resource-rich countries of the MENA region account for nearly 60 percent of the world’s oil reserves and 45 percent of the natural gas reserves. This sector will continue to attract investments, technology, and know-how.

The United States Changes Direction in the Middle East

By M.K.Bhadrakumar*

The politics of the Middle East are undergoing a period of great turbulence emanating from changes in direction of the regional policies pursued by the United States. When the ship makes a turnaround, it has to be over an arc, and it is now possible to discern the reset of the compass.

This is primarily being felt in the Obama administration’s rethink on the Syrian conflict and its decision to constructively engage with Iran. Neither is an afterthought, but rather they took time to mature…

To take Syria first, Leslie Gelb, President Emeritus at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York needs no introduction as an influential voice in the U.S. foreign policy establishment. His views on the Syrian conflict will always merit attention—especially when aired through the Voice of America (VOA).

Gelb made four key points on Syria in an exclusive interview with the VOA. First, the specter that haunts all the parties inside Syria as well as the U.S.’ friends and allies who neighbor Syria—Iraq, Turkey, Jordan, Israel—is the rise of the jihadi. Second, the elimination of the jihadis will take time because they are seasoned fighters and it is best achieved through cooperation between the Syrian regime and the moderate rebels. The basis of such cooperation could be through a “power-sharing arrangement, mainly along federal lines,” as stated by Gelb. Third, there is urgency to lay the basis of cooperation between the regime and the moderate rebels—that is, as argued by Gelb, “how they could compromise and live together.” Or else, Geneva 2 may not prove productive. And fourth, the United States is according to Gelb, “beginning to change direction” as it has “finally figured out… that the only way to stop this fighting is to work something out between the moderate rebels and the Alawites.”*

For example, the United States has stopped saying that Syria’s president, Assad, must go. That used to be the hallmark of U.S. policy. The United States no longer says that anymore. The U.S. administration says only he has lost legitimacy, and that it wants him and his government to come and participate in negotiations. So that’s changed. Also changed is the notion that the United States can simply help the rebels, as it finally realized that it does not exactly know who these rebels are and what they can do. After all, they have never gotten fully organized. And there’s a big gap, it seems, between the rebels the U.S. deals with and that council [Syrian National Coalition] in Turkey and the good rebels fighting in the field.

Indeed, it is palpable that the United States is currently supportive of the series of diplomatic initiatives Moscow has been taking during early fall 2013 in a renewed push for a Syrian peace conference. The Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov met the Syrian National Coalition (SNC) representatives in Istanbul during that time. The SNC also had come under American pressure to accept Russia’s invitation to go to Moscow to discuss the peace conference.

Equally, there has been a sea change in the U.S. Iran standoff. The probability that the ongoing negotiation of the P5+1† is high and Iran may produce an interim nuclear deal. Contrary to the widely held view that the Obama administration’s push to reach an interim agreement with Iran would be torpedoed on Capitol Hill, the Democratic leadership in the U.S. Senate, in particular the heads of the Armed Services Committee, Carl Levin, and Intelligence Committee, Dianne Feinstein, have concurred that this would be a bad time to impose new sanctions against Iran when negotiations are under way.

The former U.S. national security advisors Zbigniew Brzezinski and Brent Scowcroft have written a letter to the Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid strongly pleading, “If more sanctions are enacted now, as these unprecedented negotiations are just getting started, this would reconfirm Iranians’ belief that the United States is not prepared to make any agreement with the current government of Iran. We call on all Americans and the U.S. Congress to stand firmly with the President in the difficult but historic negotiations with Iran.”28

Indeed, Gelb himself is on record that a short-term deal “would lead to the Mideast equivalent of ending the Cold War with the Soviet Union … [and] could reduce, even sharply, the biggest threat to regional peace, an Iranian nuclear bomb, and open pathways to taming dangerous conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.”*

Therefore, there is cautious optimism that an agreement can be finalized. The leaders of Russia, China, and UK have had telephone conversations with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani. After a fall 2013 meeting President Obama, Secretary of State John Kerry, and National Security Advisor Susan Rice called with key U.S. senators, the White House issued the following statement, “We have the opportunity to halt the progress of the Iranian (nuclear) program and roll it back in key respects, while testing whether a comprehensive resolution can be achieved.”29 It warned that if there is not an initial agreement, Iran will continue making progress on increasing enrichment capacity, growing its stockpiles of enriched uranium, installing new centrifuges, and developing a plutonium reactor in the city of Arak.

Meanwhile, Iran’s surprise announcement that relinquishing its insistence that the world powers should acknowledge explicitly its right to enrich uranium deftly sidesteps a potentially tendentious aspect of the dispute and shifts the emphasis to practical steps that can be agreed on the interim.

Of course, it is not going to be a cakewalk for the Obama administration and a showdown is still very much possible between the White House and Congress regarding Iran. The conflict in Syria is not so much a contentious (and emotive) issue for the U.S. political establishment as the situation around Iran is, but everything converges ultimately on how the Obama administration will handle U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East for remainder of his presidency.

What makes this a high stakes contestation is that this is both a real time fight as well as a struggle over long-term issues. Let’s not forget, relations between the Obama administration and the Israeli government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu have entered uncharted waters and the latter has launched a full-scale attack on the entire trajectory of Obama’s Middle East policies. Compounding matters further, Israel’s concerns are not exclusively its own, but are shared by other U.S. key allies in the region, especially Saudi Arabia.

Due to a combination of circumstances including the searing experience in Iraq, crisis of the U.S. economy, and the U.S. public’s lack of support for war, all against the backdrop of a rebalance in Asia, Washington wants to reduce its military “footprint” in the Middle East, whereas, U.S.’ alliances in the region tried to pressure the Obama Administration into launching new wars against Syria and Iran. In his United Nations General Assembly speech in September 2013, President Obama virtually admitted the United States’ helplessness in modulating the Arab Spring and spelled out that Washington’s core concern in the Middle East would narrow down to four areas: protect allies from external aggression, ensure the free flow of oil, prevent proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and counter the al-Qaeda threat.

Conceivably, the United States appears to be distancing itself from its entangled alliances so as to avoid being cajoled into conflicts from its closest regional allies. In a manner of speaking, the Obama Administration is seeking an optimal regional policy to suit U.S. interests rather than Israeli or Saudi interests. This is not tantamount to a “strategic retreat” from the region and it does not necessarily mean that U.S. interventionism is gone forever. It means simply that Washington’s actions will be guided by a range of U.S. interests rather than succumbing to Israeli demands or Saudi Arabia’s regional ambitions. If this reset is carried to its logical conclusion, the balance of forces in the Middle East will be transformed beyond recognition.

![]()

* At a 3 percent rate of growth, a population doubles in size in 23 years.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

† Ibidem.

* http://archive.transparency.org/regional_pages/africa_middle_east/middle_east_and_north_africa_mena, (last accessed on 01/03/2014).

† Scale from low = 1 to high = 10.

‡ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTMNAREGTOPPOVRED/Resources/MNA_Gender_EN_Final.pdf, (last accessed on 01/03/2014).

* Ibidem.

† Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

† Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

† Ibidem.

* It should be noted, however, that Israel had great success in developing relations with independent African states beginning with the decolonization of Ghana in 1957, but due to expanding Arab influence in Africa, especially around the time of the Yom Kippur/Ramadan War of 1973, Israel was drawn closer to white-ruled South Africa, another so-called Pariah state; these ties also included controversial military cooperation.

* Ibidem, pp. 3–4.

† Ibidem.

* Ibidem, pp. 5–6.

† Ibidem.

‡ Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Ibidem.

* Mr. Bhadrakumar is a former career diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service whom devoted much of his three-decade long career to the Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran desks in the Ministry of External Affairs and in assignments on the territory of the former Soviet Union. After leaving the diplomatic service, he took to writing and contributing to The Asia Times, The Hindu, and Deccan Herald. I, Dr. Goncalves, appreciate his valuable contribution to this chapter. Mr. Bhadrakumar lives in New Delhi, India.

* Today, Alawites represent 12 percent of the Syrian population and are a significant minority in Turkey and northern Lebanon. The Alawites, also known as Alawis, are a prominent mystical religious group centered in Syria who follow a branch of the Twelver school of Shia Islam (the largest branch of Shi’a Islam), but with syncretistic elements. Alawites revere Ali (Ali ibn Abi Talib), and the name “Alawi” means followers of Ali. The sect is believed to have been founded by Ibn Nusayr during the 8th century. For this reason, Alawites are sometimes called “Nusayris,” though this term has come to have derogatory connotations in the modern era.

† The P5+1 is a group of six world powers, which in 2006 joined the diplomatic efforts with Iran with regard to its nuclear program. The term refers to the P5 or five permanent members of the UN Security Council, namely U.S., Russia, China, United Kingdom, and France, plus Germany. P5+1 is often referred to as the E3+3 (or E3/EU+3) by European countries.

* Ibidem.