The Next Emerging Markets

Overview

Two thousand years ago, everything outside of Rome was a frontier market. Three hundred years ago, everything outside of Europe was a frontier market. The emerging countries of today were the frontier as recently as 30 years ago. Now, we’d say that any country outside of the MSCI All Country World Index is a frontier market, at least from the perspective of investors in the advanced economies and especially in the United States.

Lawrence Speidell* argued that the United States, as the leading economy in the world as measured by both capitalization and trading volume, was a frontier market in 1792. At the time, the Buttonwood Agreement was executed at an outdoor location, under a buttonwood tree in New York City. It required brokers to trade only with each other and to fix commission rates. China too was a frontier market by the late 70’s and early 80’s, and today, it is the second largest economy in the world, although it is classified as an emerging market.

The same was true for Argentina, once a frontier market, but by 1896, it was about three-quarters as prosperous as the United States and had one of the world’s leading stock markets. The country’s long decline, at least in relative standing, resulted in purchasing power parity GDP per capita in 2002 that was only double the 1896 level, whereas the United States grew sevenfold over the same period. Even though Argentina has enjoyed a strong recovery and is a solidly middle-income economy, as of this writing, its equity market is still classified as a frontier market because of capital controls that were imposed in 2005. In 2011, the country was in the process of removing these controls, but in 2013 and 2014 much of its progress was derailed, and inflation is accelerating and projected to hit 40 percent in 2014. Nonetheless, most frontier markets are more developed than we think, and set for fast economic growth.

Frontier markets are sometimes referred to as “pre-emerging markets.” These are countries with equity markets that are less established, such as Argentina, Kuwait, and Bangladesh. They tend to be characterized by lower market capitalization, less liquidity and, in some cases, earlier stages of economic development. But such markets are not just growth markets in distant places; they represent more than 1.2 billion people. These emerging and frontier countries are also placing increasing demands on the world’s resources, as they become intensive consumers of basic commodities to support their infrastructure development and manufacturing. In the 1950s, the U.S. Interstate Highway System was built, and China is building its equivalent now. This trend is echoed in railway construction, power plant construction, and new building and bridge construction. And it is not just China either. Developing countries around the world are undertaking such projects.

In the words of Speidell,

It is easy to read articles with negative headlines and decide to avoid these markets. It is easy to think of only “big men” dictators and desperate poverty. But a traveler who reads only the headlines might also avoid Los Angeles and New York City. The truth is that most people in frontier countries are hard workers. They are trying to get an education, get a job, raise a family, and live in peace. They know all about Hollywood movie stars, basketball, and the World Cup. And they know a lot about getting by with less. It has been said, “they’ve been doing so much with so little for so long, they could do anything with nothing.”*

For several decades, frontier markets have been caught in a vicious circle of poverty, with little ability to develop savings for investment in future growth. What investment occurred in frontier countries was done by colonial powers that took out more than they put in. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is highly correlated with GDP growth and can be used as a measure of how the developing economies are faring in globalization. As FDI inflows increase in these markets, we believe that the frontier market growth opportunity is similar in many ways to the opportunity that existed 20 years ago for emerging markets, especially taking into consideration many of the mineral resources these countries have, as depicted in Figure 5.1.

Nonetheless, due to its small, unpopular, and illiquid economies these countries have not yet fully joined the global investment community. Nonetheless, many have already joined the global economic community, as several of these countries have matured, improved their economic and trading policies, strengthen their institutions, achieved greater global credibility, and, in various cases, hoarded substantial foreign exchange reserves.

Figure 5.2 Percentage change in MSCI frontier market index for 2013

Source: MSCI, Reuters

Figure 5.2 shows how frontier markets such as Kenya, Bulgaria, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have improved more than 40 percent during 2013. Note that most of them experienced much more growth than developed markets (advanced economies), which averaged about 12 percent, and emerging markets at negative five percent.

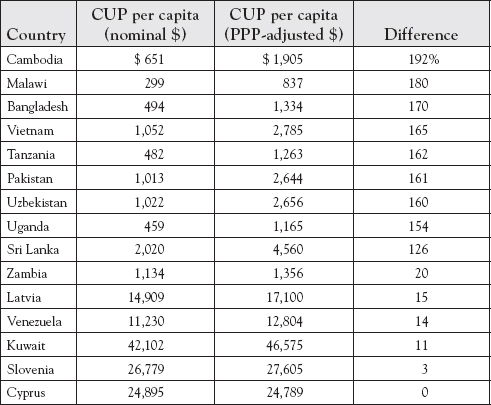

When assessing frontier markets one should consider purchasing power parity (PPP) figures because they take into account the living standards of local people who may earn little but can live well because their money can go far when they buy inexpensive local products and services. When evaluating a country’s GDP at PPP exchange rates it takes into consideration the sum value of all goods and services produced in the country valued at prices prevailing in the United States. This is the measure most economists prefer when looking at per-capita welfare and when comparing living conditions or use of resources across countries.

For instance, as shown in Figure 5.3, in Cambodia, Malawi, and Bangladesh, local prices are extremely cheap, whereas in Kuwait, Slovenia, and Cyprus, they are close to world levels. In contrast to these countries, Denmark’s GDP per capita in nominal 2008 dollars is $46,314, but prices are so high that on a PPP basis, it is only $32,333.*

Figure 5.3 GDP per capita comparison: nominal dollars and PPP-adjusted dollars, 2008

Source: Speidell, Lawrence*

An analysis of PPP GDP per capita over the past 30 years shows that China started behind India ($250 versus $415 in 1980) but has now surpassed it ($5,962 versus $2,972 as of 2008). China is in a quest for continuous and significant geopolitical gains through its investments in frontier countries, whereas many advanced economies (particularly in the West) have cut back because of political preferences and budget pressure from the current economic slowdown. India is another emerging country that is active in Africa, which is no coincidence because for generations, a large number of Africa’s entrepreneurs have been of Indian heritage. Even Russia has joined the skirmish, with then President Medvedev touring Egypt, Nigeria, Angola, and Namibia back in June 2009 in search of trade and investment deals.

The breakup of the Soviet Union dramatically affected the economies of the constituent members. By far the largest is Russia, where GDP per capita fell from $9,052 in 1989 to $6,303 in 1996 (a 31 percent decrease, which is more severe than the Great Depression in the United States) before more than doubling to $13,392 in 2008. In contrast, Botswana, a frontier country that fortunately discovered diamonds shortly after gaining independence in 1962, has shown dramatic improvement in its GDP per capita.

Progress, however, has not been across the board, as monetary and fiscal policies, FDI inflow imbalances, and stock vulnerabilities vary widely across these economies. This situation is aggravated by the fact the mainstream media tend to emphasize negative news of conflicts, violence, drought, flood, and human suffering in frontier markets, causing public opinion to categorize them with negative connotations. Behaviors such as of Robert Mugabe, president of Zimbabwe, who allowed inflation to reach an absurd 231,000,000 percent in 2008 is an example of such news that foster the development of a general prejudice, such as not trusting any government in Africa.

We believe each country should be judged on its own merits. For instance, in the frontier countries of Africa and Asia, the financial sector for consumers is almost totally undeveloped. According to Speidell, “Ghana, for example, has 22 million people but only 1.5 million bank accounts, fewer than 500,000 debit cards, and almost no credit cards. Nigeria has 148 million people and only 20 million bank accounts. Mortgages and auto loans are practically unheard of in these countries. Many banks in frontier countries take customers’ deposits and pay low interest rates of 2–4 percent.”* Then, they simply make government and commercial loans at 10 percent or more. Net interest margins are often greater than five percent, and one bank in Malawi recently told me that its net interest margin is 15 percent.

Below is a brief highlight of some of the most important frontier markets. This list is not extensive and not necessarily in any order of magnitude. It just provides an overall picture of the typical opportunities and challenges faces by these countries. For more in depth information, please refer to our other book titled “Frontier Markets, the Next Emerging Bloc,” by the same publisher.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a country the size of the state of Iowa in the United States. It is a moderate, secular, and democratic society, ranked the seventh most populated nation in the world, with 160 million (larger than Russia). Bangladesh has a big potential market for foreign investors, with a growing garment sector providing steady export-led economic growth and a rapidly developing market-based economy, on the cusp of attaining lower-middle income status of over $1,036 GDP per capita, thanks to consistent annual GDP growth averaging six percent since the 90s.

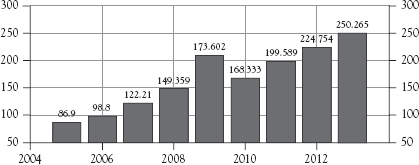

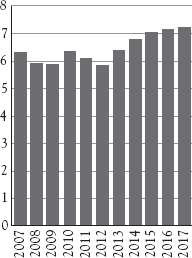

Since 1976, the Investment Corporation of Bangladesh (ICB) has been a catalyst in fostering rapid economic growth. Now the local economy is growing at full tilt, and depicted in Figure 5.4, with GDP growth projected to climb from about 5.8 percent in 2012 to around 7.2 percent in 2017. Bangladesh’s economy grew by above six percent on average over the last four years and is set to continue growing by six percent in 2014.

Figure 5.4 Bangladesh GDP growth projection through 2017

Source: IMF

Bangladesh has a lot of potential for rapid economic growth, as show in Figure 5.4. Over the past 20 years the country’s GDP has expanded on average five percent a year and is now considered one of the most attractive destinations for investment in the region. It has already surpassed other South East Asian countries in a number of fundamental economic and development indicators.

The country has gone through an extensive restructuring of its economy. Since the 1970s it has been fighting to modernize its systems, produce top entrepreneurs and broaden the base of investments in the country—and the hard work is paying off. Fostering development is still a main challenge in Bangladesh, and for some time the government strategy has been to privatize the numerous companies that were nationalized after independence. The country had a socialist economy after its independence in 1971, and around that time it nationalized all industries. However, the country has since revisited its economic policy as it undergoes reforms to stimulate at the creation of experienced entrepreneurs, managers, administrators, engineers, and technicians due to lack of private initiative.

The Bangladesh Chamber of Commerce and Industry (BCCI) has recently announced that it expects that by 2030 Bangladesh should be among the 30 largest economies in the world; it currently is the 58th largest.

Egypt

Egypt is another overlooked economy, which has lately been politically unstable as a result of the Arab Spring that spread through the Middle East, causing massive damage to its economy. After the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013, one year after he took office, Egypt entered another phase of political uncertainty.

According to the African Development Bank Group (AEBG),* Egypt’s economic growth has moderated, standing at just above two percent in both the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 fiscal years. In 2012–2013, the resilience of private consumption (81.2 percent of GDP) and the munificence of government consumption (11.7 percent of GDP) kept the economy from sliding into recession, as investment (14.2 percent of GDP) and exports (17.6 percent of GDP) remained weak. Unceasing violent protests and political instability have adversely affected manufacturing (15.6 percent of GDP), trade (12.9%) and tourism (3.2 percent). Only traditional sectors such as agriculture (14.5 percent of GDP) and mining (17.3 percent) have remained relatively unscathed.

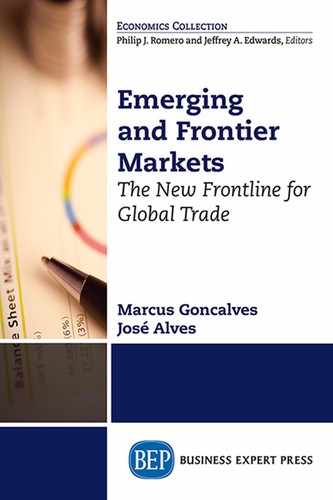

Egypt is, however, the third largest economy in Africa, and remains an important emerging market in that region, as it controls and draws significant revenues from the Suez Canal. Also according to the AEBG* projections, as depicted in Figure 5.5, the countries economy is expected to continue to grow at consistent pace.

The country’s GDP was worth $257.29 billion in 2012, and about 0.41 percent of the world economy. The country’s ability to withstand the financial burden of the revolution, for now at least was helped by the remarkable growth it posted up until December 2011. A financial reform program that began in 2003 had also helped create a well-capitalized and well-managed banking system. But for Egypt’s economy to pick up, much will depend on how the political process evolves over the coming months.

Indonesia

Indonesia, the fourth-largest country in the world by population, not only is a G-20 economy, but it also boasts an already significant and growing middle class transitioning to democracy. The country has relatively low inflation and government debt, is rich in natural resources including oil, gas, metals, and minerals. Recently, with the fall of its currency, the rupiah, exports received a major boost. The country is less reliant on international trade, which enabled it to grow despite the global financial crisis, as domestic demand constituted the bulk of output in Indonesia, about 90 percent of real GDP.

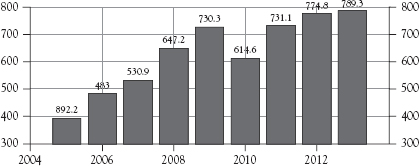

The Indonesian economy has recorded strong growth over the past few decades, notwithstanding the sharp economic contraction that occurred during the 1997–1998 Asian financial crises, as depicted in Figure 5.6. In recent years, the firm pace of economic expansion has been accompanied by reduced output volatility and relatively stable inflation. Indonesia’s economic performance has been shaped by government policy, the country’s endowment of natural resources and its young and growing labor force. Alongside the industrialization of its economy, Indonesia’s trade openness has increased over the past half century.

This strong pace of growth has seen Indonesia become an increasingly important part of the global economy. It is now the fourth largest economy in East Asia*—after China, Japan, and South Korea—and the 15th largest economy in the world on a PPP basis. Furthermore, its share of global output, currently just under 1½ per cent, is expected to continue to rise over the years ahead.

Figure 5.6 Indonesia real GDP from 1980 through 2016 (log scale)

Source: IMF

Nigeria

As the largest African nation by population, Nigeria is projected to have the highest GDP growth in the next few years and perhaps for the next several decades as depicted in Figure 5.7. In 2014, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) recalculated the value of GDP based on production patterns in 2010, increasing the number of industries it measures to 46 from 33 and giving greater weighting to sectors such as telecommunications and financial services. The revised figure surpassed South Africa’s as the largest on the continent after the West African nation overhauled its gross domestic product data for the first time in two decades.

Oil and agriculture account for more than 50 percent of its GDP, while petroleum products account for 95 percent of exports, while the industrial and the service sectors are also on the rise. This economic growth potential invites a number of FDI initiatives, mostly from China, the United States, and India. The challenge, however, is with its legal framework and financial markets regulations, which leave much to be desired.

Nonetheless, while the revised figure makes Nigeria the 26th-biggest economy in the world, the country lags in income per capita, ranking 121 with $2,688 for each citizen.

Pakistan

Pakistan is another frontier market, which we believe has a lot of potential for growth based on its rising population and middle class, rapid urbanization and industrialization, and ongoing, even though slowly, economic reforms. The country has important strategic endowments and development potential, as it is located at the crossroads of South Asia, Central Asia, China, and the Middle East and is thus at the fulcrum of a regional market with a vast population, large and diverse resources, and untapped potential for trade. The increasing proportion of Pakistan’s working-age population provides the country with a potential demographic dividend but also with the critical challenge to provide adequate services and increase employment.

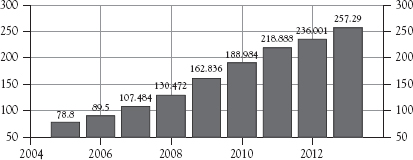

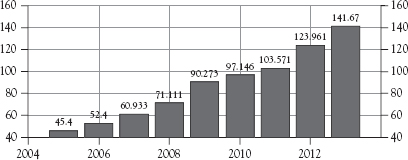

The country has experienced significant progress for several decades now, at an average rate of 4.9 percent GDP growth, as depicted in Figure 5.8. But, despite such positive economic indicators, Pakistan is still one of the poorest and least developed countries in Asia, with political instability, widespread corruption and lack of law enforcement hampering private investment and foreign aid.

Nonetheless, the country faces significant economic, governance and security challenges to achieve durable development outcomes. The persistence of conflict in the border areas and security challenges throughout the country is a reality that affects all aspects of life in Pakistan and impedes development. A range of governance and business environment indicators suggest that deep improvements in governance are needed to unleash Pakistan’s growth potential.

Pakistan also faces significant economic challenges. The sharp rise in international oil and food prices, combined with recurring natural disasters like the 2010 and 2011 floods had a devastating impact on the economy. As Pakistan recovered from the 2008 global crisis, its GDP grew 3.8 percent in 2009–2010. The 2010 floods, with an estimated damage of over $10 billion, caused growth to slow down to 2.4 percent. In 2011–2012, however, the Pakistan economy grew by an estimated 3.7 percent, against the pre-flood targeted growth rate of 4.2 percent.

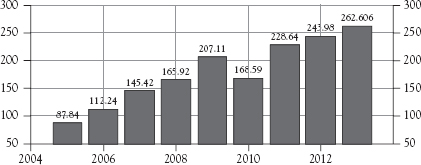

The Philippines

The Philippines has shown a strong economic progress in the past few years, as shown in Figure 5.9, posting the highest GDP growth rates in Asia for most of 2013. The country weathered the global economic crises very well owing to significant progress made in recent years on fiscal consolidation and financial sector reforms, which contributed to a marked turnaround in investor sentiment, fostering significant FDI inflows. The challenges, as a newly industrialized country, are that the Philippines are still an economy with a large agricultural sector, although services are beginning to dominate the economy.

Robust private consumption and investment drove economic growth in the Philippines higher in 2013. Strong growth is expected to continue in the forecast period, though moderating from last year. Rehabilitation and reconstruction in areas hit by natural disasters may have a significant impact on the economy in late 2014 or 2015. Inflation is forecasted to pick up this year but remain within the central bank’s target range. The challenge is to translate solid economic growth into poverty reduction by generating more and better jobs.

Turkey

Turkey’s economy, as depicted in Figure 5.10, much like the Philippines, has been growing at a fast pace, and for much of the same reasons. Rapid industrialization coupled with steady economic reforms has made Turkey an attractive emerging market. In the summer of 2013, however, Turkish economy suffered with civil unrest and the United States taper talk. The country’s political stability, unique geographical location on the border of Europe and Asia, market maturity and economic growth potential, positions Turkey’s economy to remain prone for FDI inflows.

The ruling Development and Justice Party (AKP) secured a clear victory in the local elections on March 30, 2014, confirming the prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s dominance of the AKP and Turkish politics. Mr. Erdogan and his party are well placed ahead of the presidential and legislative elections due in August 2014 and June 2015, respectively. But deep social and political polarization risks exacerbate economic difficulties arising from shifting global financial flows and a weaker lira.

Economic growth lost momentum in the course of 2013, as capital market tensions pushed interest rates up. Credit and private demand decelerated. Export growth fell, notably due to rapidly declining gold sales. Political tensions have dented confidence, provoking capital outflows, and forcing the central bank to raise interest rates sharply in early 2014. Growth is projected to remain subdued through mid-2015, while the current account deficit will remain very high.

Vietnam

Vietnam, with agriculture still accounting for 20 percent of its GDP has an industry and services sector that continues to grow. The major challenge with Vietnam is still its authoritarian regime, which causes its economy to be split between state planned and free market sections. In addition, its economy is still volatile, despite the much progress, due to relatively high inflation, lack of transparency into government policy, and the fact that the country virtually lacks large enterprises.

Vietnam is a development success story. Political and economic reforms launched in 1986 have transformed Vietnam from one of the poorest countries in the world, with per capita income below $100, to a lower middle-income country within a quarter of a century with per capita income of $1,130 by the end of 2010. The ratio of population in poverty has fallen from 58 percent in 1993 to 14.5 percent in 2008, and most indicators of welfare have improved. Vietnam already has attained five of its ten original Millennium Development Goal targets and is well on the way to attaining two more by 2015.

Vietnam has been applauded for the equity of its development, which has been better than most other countries in similar situations. The country has been growing at a sturdy pace, as depicted in Figure 5.11. The country is playing a more visible role on the regional and global stage, having successfully chaired the 2009 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group and the IMF, and carried out the Chairmanship of the ASEAN in 2010.

Vietnam now has a love affair with the motorbike, which started 10 years ago with cheap imports from China. The cheapest ones cost as little as $300, but the more coveted Hondas and Suzuki’s are about $1,000, and luxury models cost twice that amount. The government has wisely discouraged car sales by implementing a 250 percent tax, so the streets of Saigon are not nearly as hopelessly clogged as those of Dhaka or Mumbai.

Recommendations

Overall, we see significant opportunities in frontier markets, especially considering its solid capital base, young labor pool, and improving productivity, particularly in Africa, where we believe the sub-Saharan region eventually will overtake China and India. It is plausible to assume that Africa’s economy will grow from $2 trillion to $29 trillion by 2050, greater than the current economic output of both the United States and the eurozone.

We must consider, however, the frontier market’s deepening economic ties to China, which make it vulnerable to a slowing Chinese economy. Also, frontier markets are not without risks, as local politics are complex, and there are still several pockets of corruption and instability. Further, liquidity is scarce, transaction costs can be steep, and currency risk is real. As if that’s not enough to worry about, there’s also the risk of nationalization.

That said, we do not subscribe to the idea that emerging markets are in “crisis.” The growth economic index for these countries has soared up 20.2 points, far ahead of the United States, Europe and Japan’s 12 points. In our view, the hard evidence in the data contradicts the notion that emerging markets are suffering an economic crisis, especially considering that most emerging markets also have a fast-growing middle class of consumers. The so-called Fragile-Five (Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey) and other emerging economies that run chronic current-account deficits may be at risk, but due to a liquidity crunch. There are many other emerging markets performing very well economically, reflected in their stock markets, which continue to outperform the S&P 500 Index year-to-date.

As the emerging markets of today move on to become part of the advanced economies of the world, the stage is set to bring along a new set of emerging candidates from the frontier markets.

![]()

* Speidell, Lawrence (2011-05-13). Frontier Market Equity Investing: Finding the Winners of the Future (Kindle Locations 67–68). CFA Institute. Kindle Edition.

* Speidell, Lawrence (2011-05-13). Frontier Market Equity Investing: Finding the Winners of the Future (Kindle Locations 132–136). CFA Institute. Kindle Edition.

* Speidell, Lawrence (2011-05-13). Frontier Market Equity Investing: Finding the Winners of the Future (Kindle Locations 612–615). CFA Institute. Kindle Edition.

* According to Trading Economics as of 06/13/2014: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/denmark/gdp-per-capita

* Speidell, Lawrence (2011-05-13). Frontier Market Equity Investing: Finding the Winners of the Future (Kindle Location 243). CFA Institute. Kindle Edition.

* Speidell, Lawrence (2011-05-13). Frontier Market Equity Investing: Finding the Winners of the Future (Kindle Locations 493–498). CFA Institute. Kindle Edition.

* http://www.afdb.org/en/countries/north-africa/egypt/egypt-economic-out-look/

* http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/en/

* Unless otherwise specified, East Asia refers to the economies of China, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines.