Overview

According to a recent study from the Peterson Institute,* a think-tank, from 1960 to the late 1990s just 30 percent of countries in the developing world, for which figures are available, managed to increase their output per person faster than the United States, thus achieving what is called “catch-up growth.” That catching-up was somewhat apathetic; the gap closed at just 1.5 percent a year. From the late 1990s, however, the tables were turned. The researchers found 73 percent of emerging economies outpacing the United States, and doing so on average by 3.3 percent a year. Some of this was due to slower growth in America, but not all.

This outstanding growth of emerging markets in general and in particular the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) has transformed the global economy in many ways, as commodity prices soared and the cost of manufactures and labor sank. Such growth also caused a significant decline on global poverty rates, which has tumbled, even though income inequality has grown around the world. Social mobility has decreased at similar rate. In addition, gaping economic imbalances has fueled an era of global financial vulnerability and contributed to the foundation for a global crisis. A growing and vastly more accessible pool of labor in emerging economies has played a significant part in both wage stagnation and rising income inequality.

China’s pivot toward liberalization and global markets came at a propitious time in terms of politics, business, and technology. Rich economies were feeling relatively relaxed about globalization and current account deficits. At the time China and India were experiencing astronomic growth rates, the United States was not paying much attention. The Bill Clinton administration was characterized by an economic boom and market confidence. No one was concerned about the growth of Chinese industry or offshoring jobs to India.

The BRICS period arrived at the end of a century in which global living standards had diverged remarkably. Toward the end of the 19th century, America’s economy overtook China’s to become the largest on the planet. By 1992, China and India—home to 38 percent of the world’s population—were producing just seven percent of the world’s output, while six rich countries which accounted for just 12 percent of the world’s population produced half of it. In 1890, an average American was about six times better off than the average Chinese or Indian. By the early 1990s he was doing 25 times better.

The bloc was originally known as “BRIC” before the inclusion of South Africa in 2010. Jim O’Neill coined the acronym in a 2001 paper entitled, “Building Better Global Economic BRICs.”1 The acronym has come into widespread use as a symbol of the apparent shift in global economic power away from the developed G-7 economies toward the developing world. The BRICS members are all emerging economies, either at a developing or newly industrialized stage, but distinguished by their large, fast-growing economies2 and significant influence on regional and global affairs. All five countries are members of the G-20.

As of 2013, these five BRICS countries represent almost three billion people, with a combined nominal GDP of $16.039 trillion,3 and an estimated $4 trillion in combined foreign reserves.4 Impressively, their growing rates and the size of their economies sets them aside in a special way, as depicted in Figure 1.1. If we weigh their GDP in purchasing-power parity* (PPP) terms, these countries are the only $1 trillion dollar economies outside the rich, world club, OECD.

Advanced economies such as the EU, view the BRICS as less interested in shared ideas of a multilateral world, and more inclined toward a nationalistic, multipolar world that emphasizes their own newly found strengths and interests. The result is fading authority and consensus on the world stage. The cold war spheres of influence between two powers are long gone. The new world order of U.S. dominance is diminishing. But no clear leadership or rules have yet replaced this. New struggles of trends such as human rights and democracy—and sovereignty—still have to be decided.

Figure 1.1 The significant growth of the BRIC compared with emerging markets (overall) and the U.S. economy

Source: IMF, The Economist

The shift toward the emerging economies will continue. But its most tumultuous phase seems to have more or less reached its end. Growth rates in all the BRICS have dropped. The nature of their growth is in the process of changing, too, and its new mode will have fewer direct effects on the rest of the world. The likelihood of growth in other emerging economies having an effect in the near future comparable to that of the BRICS in the recent past is low; they do not have the potential for catch-up the BRICS had in the 1990s and 2000s. The BRICS’ growth has changed the rest of the world economy in ways that will dampen the disruptive effects of any similar surge in the future. The emerging giants will grow larger, and their ranks will swell, but their tread will no longer shake the Earth as once it did.

Recent developments, such as the danger of a property bubble in China, a decline in world trade, and volatile capital flows in emerging markets, could derail the global economic recovery and have a lasting impact. Arguably, in our view, 2013’s economic deceleration to a large extent reflects the inability of global leaders to address the many challenges that were already present from 2001 to 2012.

Policymakers around the world remain concerned about high unemployment and the social conditions in their countries. The political brinkmanship in the United States continues to affect the outlook for the world’s largest economy, while the sovereign debt crises and the danger of a banking system meltdown in peripheral eurozone countries remain unresolved. The high levels of public debt coupled with low growth, insufficient competitiveness, and political gridlock in some European countries are still stirring financial markets’ concerns about sovereign default and the viability of the euro.

Given the complexity and the urgency of the situation, advanced economies around the world, in particular the United States and European countries are facing difficult economic management decisions with challenging political and social ramifications. Although European leaders do not agree on how to address the immediate challenges, there is recognition that, in the longer term, stabilizing the euro and putting Europe on a higher and more sustainable growth path will necessitate improvements to the competitiveness of the weaker member states.

Meanwhile, emerging markets are coping with the consequence of advanced economies’ debt. In our view, given the expected slowdown in economic growth in China, India, and other emerging markets, reinforced by a potential decline in global trade and volatile capital flows in the next five to eight years, it is not clear which regions of the world can drive growth and employment creation in the short to medium term, but we believe the BRICS will play a major role in this process. Africa, as well as the whole MENA bloc, should see high growth levels in the next decade.

When we look at advanced economies as compared to emerging markets, the IMF5 accurately estimated that, in 2012, the eurozone would have contracted by 0.3 percent, while the United States would have continued to experience a weak recovery with an uncertain future. Large emerging economies such as the BRICS are growing somewhat less than they did in 2011, but still growing at around 4–5 percent annually. Meanwhile, other emerging markets such as ASEAN also continue to show robust growth rates, around 5–7 percent, while the MENA as well as sub-Saharan African countries continue to gain momentum.

According to John Hawksworth and Dan Chan at PWC,6 the world economy is projected to grow at an average rate of just over three percent per annum from 2011 to 2050, doubling in size by 2032 and nearly doubling again by 2050. Meanwhile, China is projected to overtake the United States as the largest economy by 2017 in PPP terms and by 2027 in market exchange rate terms. India should become the third ‘global economic giant’ by 2050, well ahead of Brazil, who is expected to become the fourth largest economy, ahead of Japan. Hawksworth and Chan also argue that Russia may overtake Germany to become the largest European economy before 2020 in PPP terms and by around 2035 at market exchange rates. Emerging economies such as Mexico and Indonesia could be larger than the UK and France by 2050, and Turkey larger than Italy.

The American or EU citizen who has travelled to India knows that his money stretches further than it does at home. To be precise, one can buy 2.8 times as much in India with a dollar’s worth of rupees than one can with a dollar in the United States, according to the IMF.7 This is because India’s prices are only about 35 percent of America’s, when converted into a common currency at market exchange rates. This magic is not unique to India of course. It applies across most developing countries. This is not true, however, when Americans visit countries like Switzerland, where prices are 175 percent of America’s level, Denmark at 153 percent, or Australia with 149 percent.

In the biggest emerging economies, however, this magic is fading. Ten years ago, Brazil’s price level was only 40 percent of America’s, but as of July of 2013, it was 90 percent. China’s also has risen from 39 percent to 67 percent over the same period, while Russia’s has also soared from 31 percent to almost 83 percent. Taken together, the BRICs have become notably more expensive over the past decade. Their combined price level rose rapidly toward advanced economies levels from 2003 to 2011, before plateauing in the past two years.

This dramatic convergence of price levels is an underrated economic force. It is one telling reason why the BRICS’ dollar GDP is now worth exceedingly more than anyone expected back in 2003, when O’Neill released the first of his long-range projections of the BRICS’ economic fate over the next half-century. At the time, the projections raised eyebrows. Now that the BRIC economies have faltered, O’Neill’s whole thesis has been sneered at. But, looking back at his attempt to look forward, O’Neill was, if anything, too conservative about his forecast. The BRICS combined dollar GDP will be 70 percent bigger in 2013 than O’Neill/Goldman Sachs had projected ten years ago.

Some of that over performance is due to the fact the BRICS have grown faster over the past decade than Goldman Sachs expected. China, for instance, is still growing faster than envisioned, despite its slow-down from double-digits growth rates. The same is not true for the other three countries, although a big part of the overrun is due to the fact the BRICS became pricier faster than Goldman Sachs foresaw. The following is a short profile of the BRICS, their strengths and weaknesses as of 2013.

Brazil

Following more than three centuries under Portuguese rule, Brazil gained its independence in 1822, maintaining a monarchical system of government until the abolition of slavery in 1888 and the subsequent proclamation of a republic by the military in 1889. Brazilian coffee exporters politically dominated the country until populist leader Getulio Vargas rose to power in 1930. Brazil is by far the largest and most populous country in South America. The country underwent more than a half-century of populist and military government until 1985, when the military regime peacefully ceded power to civilian rulers.

Brazil continues to pursue industrial and agricultural growth and development of its interior. Exploiting vast natural resources and a large labor pool, it is today South America’s leading economic power and a regional leader, one of the first in the area to begin an economic recovery since 2008. Highly unequal income distribution and crime remain pressing problems. Characterized by large and well-developed agricultural, mining, manufacturing, and service sectors, Brazil’s economy outweighs that of all other South American countries, and Brazil is expanding its presence in world markets.

Since 2003, Brazil has steadily improved its macroeconomic stability, building up foreign reserves, and reducing its debt profile by shifting its debt burden toward real denominated and domestically held instruments. In 2008, Brazil became a net external creditor and two ratings agencies awarded investment grade status to its debt. After strong growth in 2007 and 2008, the onset of the global financial crisis hit the country in 2008. Brazil experienced two quarters of recession, as global demand for Brazil’s commodity-based exports declined and external credit dried up. However, Brazil was one of the first emerging markets to begin a recovery. In 2010, consumer and investor confidence revived and GDP growth reached 7.5 percent, the highest growth rate in the past 25 years. But rising inflation led the government to take measures to cool the economy; these actions and the deteriorating international economic situation slowed growth to 2.7 percent in 2011 and 1.3 percent in 2012. Unemployment is at historic lows and Brazil’s traditionally high level of income inequality has declined for each of the last 14 years.

Brazil’s historically high interest rates have also made it an attractive destination for foreign investors. Large capital inflows over the past several years have contributed to the appreciation of the currency, hurting the competitiveness of Brazilian manufacturing and leading the government to intervene in foreign exchange markets and raise taxes on some foreign capital inflows. President Dilma Rousseff has retained the previous administration’s commitment to inflation targeting by the central bank, a floating exchange rate, and fiscal restraint. In an effort to boost growth, in 2012 the administration implemented a somewhat more expansionary monetary policy that has failed to stimulate much growth.

According to Professor Klaus Schwab’s Global Competitiveness Report8 at the World Economic Forum, Brazil has made significant improvement in its macroeconomic condition, despite its still-high inflation rate of nearly seven percent. Schwab argues that, overall, Brazil’s fairly sophisticated business community enjoys the benefits of one of the world’s largest internal markets (seventh in the world), which allows for important economies of scale and continues to have fairly easy access to financing for its investment projects.

Notwithstanding these strengths, the country also faces important challenges, beginning with the lack of trust in its politicians, which remains low, as well as government efficiency, which is also low, due to excessive government regulation and wasteful spending. The quality of transport infrastructure, which was the cause of recent riots in Brazil during the fall of 2013, remains an unaddressed long-standing challenge. The quality of education is another challenge for the government, affecting Brazil’s ability to compete abroad, unable to match the increasing need for a skilled labor force. Moreover, despite the red tape, government bureaucracies, and increasing efforts to facilitate entrepreneurship, especially for small companies, the time needed to start a business remains among the highest in Schwab’s countries sample (130th and 139th, respectively). Taxation still is perceived to be too high and to have distortionary effects to the economy.*

With regards to social sustainability, Brazil’s overall good performance masks a number of environmental concerns, such as the deforestation of the Amazon; the country possesses one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world. In general, outside of Brazil, the other four BRICS (Russia, India, China, and South Africa) all reveal significant weaknesses in both dimensions of sustainable competitiveness.

In April 2014, Finance Minister Guido Mantega held that the Brazilian economy is expected to expand 2.3 percent in 2014, which was slightly below his February’s estimate of 2.5 percent. For the first half of 2014, economic data seemed to support his assertions showing a deceleration of the economy, as suggested by the government. Economic activity rose a timid 0.2 percent month-on-month in February, which was down from the 2.3 percent expansion tallied in January. Industrial output fell a monthly 0.5 percent in March, which was also down from the flat reading tallied in April. In addition, forward-looking indicators registered strong deteriorations in April, as both consumer and business confidence fell to the lowest levels in nearly five years. Will the World Cup, which starts in June, change such trend? Historically, such events do change positivity these economic outlooks, but unfortunately, it tends to be a temporary phenomenon.

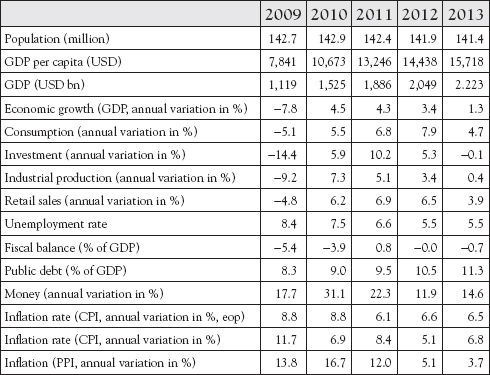

Notwithstanding, Brazil’s economic data remains positive. As depicted in Figure 1.2, unemployment and public debt have consistently decreased since 2009, and per capita GDP has grown about 33 percent in the past five years (mean of 6.6 percent increase annually).

Russia

Founded in the 12th century, the Principality of Muscovy was able to emerge from over 200 years of Mongol domination (13th–15th centuries) and to gradually conquer and absorb surrounding principalities. In the early 17th century, a new Romanov Dynasty continued this policy of expansion across Siberia to the Pacific. Under Peter I (ruled 1682–1725), hegemony was extended to the Baltic Sea and the country was renamed the Russian Empire. During the 19th century, more territorial acquisitions were made in Europe and Asia.

Defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 contributed to the Revolution of 1905, which resulted in the formation of a parliament and other reforms. Repeated devastating defeats of the Russian army in World War I led to widespread rioting in the major cities of the Russian Empire and to the overthrow in 1917 of the imperial household. The communists under Vladimir Lenin seized power soon after and formed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The brutal rule of Iosif Stalin (1928–53) strengthened communist rule and Russian dominance of the Soviet Union at a cost of tens of millions of lives.

The Soviet economy and society stagnated in the following decades until General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev (1985–91) introduced glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) in an attempt to modernize communism, but his initiatives inadvertently released forces that by December 1991 splintered the USSR into Russia and 14 other independent republics. Subsequently, Russia has shifted its post-Soviet democratic ambitions in favor of a centralized semi-authoritarian state in which the leadership seeks to legitimize its rule through managed national elections, populist appeals by President Putin, and continued economic growth. Russia has severely disabled a Chechen rebel movement, although violence still occurs throughout the North Caucasus.

Russia has undergone significant changes since the collapse of the Soviet Union, moving from a globally isolated, centrally planned economy to a more market-based and globally integrated economy. Economic reforms in the 1990s privatized most industries, with notable exceptions in energy and defense-related sectors. The protection of property rights is still weak and the private sector remains subject to heavy state interference.

In 2011, Russia became the world’s leading oil producer,9 surpassing Saudi Arabia. Russia is also the second-largest producer of natural gas, holding the world’s largest natural gas reserves, the second-largest coal reserves, and the eighth-largest crude oil reserves. Russia is also a top exporter of metals such as steel and primary aluminum. Notwithstanding, Russia’s reliance on commodity exports, as in Brazil’s, makes it vulnerable to boom and bust cycles that follow the volatile swings in global prices. Hence, the government, since 2007, embarked on an ambitious program to reduce this dependency and build up the country’s high technology sectors, but with few visible results so far.

The economy had averaged seven percent growth in the decade following the 1998 Russian financial crisis, resulting in a doubling of real disposable incomes and the emergence of a middle class. The Russian economy, however, was one of the hardest hit by the 2008–2009 global economic crisis as oil prices plummeted and the foreign credits that Russian banks and firms relied on dried up.*

According to the World Bank10 the government’s anti-crisis package in 2008–2009 amounted to roughly 6.7 percent of GDP. The economic decline bottomed out in mid-2009 and the economy began to grow again in the third quarter of 2009. High oil prices maintained Russian growth in 2011–2012 and helped Russia reduce the budget deficit inherited from 2008–2009, which helped Russia reducing unemployment to record lows and lower inflation.

Russia joined the WTO in 2012, which will reduce trade barriers in Russia for foreign goods and services and help open foreign markets to Russian goods and services. At the same time, Russia has sought to cement economic ties with countries in the former Soviet space through a Customs Union with Belarus and Kazakhstan, and, in the next several years, through the creation of a new Russia-led economic bloc called the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

Nonetheless, Russia is experiencing several challenges. The country has had difficulty attracting foreign direct investment and has experienced large capital outflows in the past several years, leading to official programs to improve Russia’s international rankings for its investment climate. Russia’s adoption of a new oil-price-based fiscal rule in 2012 and a more flexible exchange rate policy have improved its ability to deal with external shocks, including volatile oil prices. Russia’s long-term challenges also include a shrinking workforce, rampant corruption, and underinvestment in infrastructure.

Nevertheless, according to Klaus Schwab11 at the World Economic Forum, Russia has sharply improved its macroeconomic environment due to low government debt and a government budget that has moved into surplus, although the country still hasn’t managed to address its weak public institutions or the capacity for innovation. Hence, the country still suffers from inefficiencies in the goods, labor, and financial markets, where the situation is deteriorating for the second year in a row.

Russia’s weak level of global competition, caused by inefficient anti-monopolistic policies and high restrictions on trade and foreign ownership, contributes to this inefficient allocation of Russia’s vast resources, hampering higher levels of productivity in the economy.* Moreover, as the country moves toward a more advanced stage of economic development, its lack of business sophistication and low rates of technological adoption will become increasingly important challenges for its sustained progress. On the other hand, its high level of education enrollment, especially at the tertiary level, its fairly, good infrastructure, and its large domestic market represent areas that can be leveraged to improve Russia’s competitiveness.

According to a revised estimate released in May 2014 by Focus-Economics.com,† the Russian economy expanded 0.9 percent over the same period in Q1 of 2013, confirming concerns that the country has been facing an economic deceleration. Notwithstanding, also in May 2014, Russia and China signed a $400 billion deal in which the former will sell gas to the latter for 30 years starting in 2018. The deal is the largest gas contract Russia has ever entered into, which can potentially improve Russia’s overall economic data.

Figure 1.3 provides Russia’s economic data from 2009 through 2014. Unemployment and inflation rates have consistently decreased since 2009; per capita GDP has grown over 100 percent in the past five years (about 20 percent annual increase). While political tensions eased after Russia withdrew its troops from the Ukrainian border, capital outflows totaled $63.7 billion, which was the largest outflow since 2011 and exceeded all outflows tallied in 2013. Such outflow of capital was due to the two rounds of sanctions imposed on Russia in March and April remain in force and the threat of stronger measures has already served to erode investor confidence and trigger a massive capital flight.

India

The Indus Valley civilization, one of the world’s oldest, flourished during the third and second millennia B.C. and extended into northwestern India. Aryan tribes from the northwest infiltrated the Indian subcontinent about 1500 B.C., and then merged with the earlier Dravidian inhabitants creating the classical Indian culture. The Maurya Empire of the 4th and 3rd centuries B.C., which reached its apex under Ashoka,* united much of South Asia. The Golden Age ushered in by the Gupta dynasty (fourth to sixth centuries A.D.) saw a flowering of Indian science, art, and culture. Islam spread across the subcontinent over a period of 700 years. In the 10th and 11th centuries, Turks and Afghans invaded India and established the Delhi Sultanate. In the early 16th century, the Emperor Babur established the Mughal Dynasty, which ruled India for more than three centuries.

European explorers began establishing footholds in India during the 16th century. By the 19th century, Great Britain had become the dominant political power on the subcontinent. The British Indian Army played a vital role in both World Wars. Years of nonviolent resistance to British rule, led by Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, eventually resulted in Indian independence, which was granted in 1947. Large-scale communal violence took place before and after the subcontinent partition into two separate states, India and Pakistan.

The neighboring nations have fought three wars since independence, the last of which was in 1971 and resulted in East Pakistan becoming the separate nation of Bangladesh. India’s nuclear weapons tests in 1998 emboldened Pakistan to conduct its own tests that same year. In November 2008, terrorists originating from Pakistan conducted a series of coordinated attacks in Mumbai, India’s financial capital. Despite pressing problems such as significant overpopulation, environmental degradation, extensive poverty, and widespread corruption, economic growth following the launch of economic reforms in 1991 and a massive youthful population are driving India’s emergence as a regional and global power.

India is developing into an open-market economy, but there remain traces of its past autarkic policies. Economic liberalization measures, including industrial deregulation, privatization of state-owned enterprises, and reduced controls on foreign trade and investment, began in the early 1990s and have served to accelerate the country’s growth; growth that has averaged fewer than seven percent per year since 1997.

India’s diverse economy encompasses traditional village farming, modern agriculture, handicrafts, a wide range of modern industries, and a multitude of services. Slightly more than half of the work force is in agriculture, but services, particularly information technology and information systems (IT&IS) are the major source of economic growth, accounting for nearly two-thirds of India’s output, with less than one-third of its labor force. India has capitalized on its large educated English-speaking population to become a major exporter of information technology services, business outsourcing services, and software workers.

In 2010, the Indian economy rebounded robustly from the global financial crisis, in large part due to strong domestic demand, and growth exceeded eight percent year-on-year in real terms. However, India’s economic growth began slowing in 2011 due to a slowdown in government spending and a decline in investment, caused by investor pessimism about the government’s commitment to further economic reforms. High international crude prices have also exacerbated the government’s fuel subsidy expenditures, contributing to a higher fiscal deficit and a worsening current account deficit.

In late 2012, the Indian Government announced additional reforms and deficit reduction measures to reverse India’s slowdown, including allowing higher levels of foreign participation in direct investment in the economy. The outlook for India’s medium-term growth is positive due to a young population and corresponding low dependency ratio, healthy savings and investment rates, and increasing integration into the global economy.

India has many long-term challenges that it has yet to fully address, including poverty, corruption, violence and discrimination against women and girls, an inefficient power generation and distribution system, ineffective enforcement of intellectual property rights, decades-long civil litigation dockets, inadequate transport and agricultural infrastructure, accommodating rural-to-urban migration, limited non-agricultural employment opportunities, and inadequate availability of basic quality of life and higher education.

On the topic of education, in his New York Times bestseller Imagining India: the Idea of a Renewed Nation, the co-chairman of Infosys Technologies, Nandan Nilekani argues that “reforms that expand access are thus the most crucial for the disempowered. They are critical in bringing income mobility to the weakest and poorest groups. And this mobility is at the heart of the success of free markets: we tend to forget that a prerequisite to productivity and efficiency is a large pool of educated people, which requires in turn easy and widespread access to good schools and colleges.”12

Nilekani argues that the government of India ignores such challenges of fairness and equality at their peril. He contends that if discontent is left to fester, it will trigger enormous backlashes against open market policies, which actually is happening with Wal-Mart’s expansion in the country. In August 2013, an article in the Business Standard13 discussed Wal-Mart’s ongoing Enforcement Directorate (ED) investigation into its investment in the Bharti Group, a business conglomerate headquartered in New Delhi, India, where in 2010 the retailer giant made an investment in the form of compulsory convertible debentures (CCD). In addition, Wal-Mart was concerned with the political uncertainty in India, with the general election slated for 2014, along with the possibility of a statewide block to foreign direct investment (FDI) in retailing as a potential barrier for the company in that country.

Hence, as of 2013, India is the worst performer among the BRICS, with concerns in both areas of sustainability. Regarding social sustainability, India is not able to provide access to some basic services to many of its citizens; only 34 percent of the population has access to sanitation. The employment of much of the population is also vulnerable, which combined with weak official social safety nets, makes the country vulnerable to economic shocks. In addition, although no official data are reported for youth unemployment, numerous studies indicate that the percentage is very high.14

According to Amin,15 India’s economy was once ahead of Brazil and South Africa, but it now trails them by some 10 places, and lags behind China by a margin of 30 positions. The country continues to be penalized for its disappointing performance in areas considered basic factors of competitiveness. The country’s supply of transport and energy infrastructure remains largely insufficient and ill adapted to the needs of the economy. Indeed, the Indian business community repeatedly cites infrastructure as the single biggest hindrance to doing business, well ahead of corruption and bureaucracy. It must be noted, however, that the situation has been slowly improving since 2006.*

The picture is even bleaker in the health and basic education sectors. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report,16 despite improvements across the board over the past few years, poor public health and education standards remain a primary cause of India’s low productivity. Turning to the country’s institutions, discontent within the business community remains high regarding lack of reforms and the perceived inability of the government to push them through. Indeed, public trust in politicians has been weakening for the past three years. Meanwhile, the macroeconomic environment continues to be characterized by large and repeated public deficits and the highest debt-to-GDP ratio among the BRICS. On a positive note, inflation returned to single-digit territory in 2011.

Despite these considerable challenges, India does possess a number of strengths in the more advanced and complex drivers of competitiveness. This reverse pattern of development is characteristic of India. It can rely on a fairly well developed and sophisticated financial market that can channel financial resources to good use, and it boasts reasonably sophisticated and innovative businesses environment. As argued by Vinay Rai and William Simon in their book titled Think India,17 there is a “new India rising up, and it is going to change the world, from Bollywood to world financial markets, from IT to manufacturing, for service to design.” “In the India of today,” Rai and Simon continue, “activity in construction, in manufacturing, in innovation, abounds everywhere from large cities to small towns and rural villages. Every sector of the economy, without exception, is growing. And not just growing, but at starling rates that reach fifty to a hundred percent annually.”*

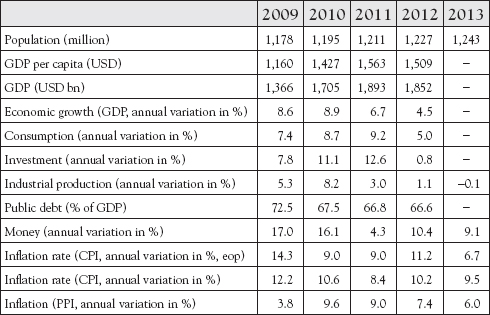

Rai and Simon argue that India is not Japan, Brazil, the EU, or even China, as India’s people, with their diversity, openness, practicality, innovation, and service orientation, are the country’s real strength. Indians creative energy, unleashed after hundreds of years of slavery and foreign rule, are driving modern India to new heights. Just imagine, by 2020, one-half of the world population of people under age of twenty-five will be in India! Mumbai has today some of the most expensive real estate in the world, with over 18 million clustered around the crescent-shaped bay, with a density more than triple of Tokyo. Electronic City, an industrial park that’s home to over hundred electronics and software firms in Bangalore, India’s Silicon Valley, is the dynamic epicenter of 21st-century India. Figure 1.4 provides an overall outlook for India’s economic data between 2009 and 2013. Per capita GDP has grown consistently since 2009 through 2012, although not significantly as Brazil and Russia, at an average rate of about 7.52 percent a year, for a total of 30 percent from 2009 through 2012 (no data was available for 2013). Public debt has also decreased significantly, a trend across all BRICS countries.

The rising of consumerism class is impressive. Their new spending power will make India the biggest cash-drawer worldwide for consumer goods and services.* The Indian consumer, due to colonial prejudices toward moneylenders, had hitherto considered taboo the buying of a house or a car on credit. Now that attitude is being debunked as the enthusiasm of Indians to consume grows, as their disposable incomes continues to rise. Hence, their new enthusiasm to take out a loan to pay for everything from television sets to a trip overseas is making bankers from around the world levitate, although in our view, it may not necessarily be a good thing for Indian families to enter into debt.

More and more banks are investing in India, either by establishing presence there or buying stake in Indian banks. The list of foreign banks in India today is impressive, including global stalwarts such as Deutsche Bank, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, and investment banks such as JM Morgan Stanley, Barclays, and Merrill Lynch.

Larry Summers, the former president of Harvard University, said in 2006 that Harvard had made a “fundamental error of judgment” in not recognizing India’s potential and promise early enough. A mistake, according to Summers, that Harvard would correct by setting up a dedicated “India Center” with an initial funding of $1 billion.

Back in 2006, the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report* ranked India highest among all BRIC nations, the 43rd most competitive country in world—out of 148 countries surveyed—versus China’s 54th at the time. In 2013, India dropped its ranking significantly, to 60th, versus China’s even more significant rise to 29th. The rest of the BRICS countries, Brazil, Russia, and South Africa, by comparison, rank 56th, 64th, and 53rd respectively.18 Stalled reforms, slowing growth, and a sliding rupee have singled India out as an underperformer on the world stage. India’s ranking declined by three places to 59th position in the Global Competitiveness Index 2012–2013 of the WEF due to disappointing performance in the basic factors underpinning competitiveness.

The fact remains, however, that India has several advantages over China, according to the WEF Competitiveness report:†

•China has less chance for innovation in its relatively closed state-controlled market. India, the largest democracy in the world, has a free market and a free press, which empowers its people to be innovative and creative, even at the grassroots levels.

•India’s growing workforce of people below the age of 25 is a major competitive weapon in its arsenal, the benefits of which will soon start trickling in. China’s one-child policy, although under revision, while reducing pressure of a population growing too fast and is under revision is making the nation age faster as well.

•Many Indians speak fluent English while most Chinese don’t.

•Both India and China (even more so than India) are known for manufacturing, but India has lured several fortune 500 companies to set up high-end/high-tech research and development centers on their soil.

•Efficient capital markets, quality of public institutions, and a sound judicial system accounts for India besting its competitors.19

The Goldman Sachs analysis20 that puts the United States in third place economically by 2050, behind India and China, while it seems so unlikely to many, seems more logical when you recognize that the brightest 25 percent of India population outnumber the entire population of the United States. Will the same still be true in 2050? If we do the math, the answer is a resounding yes.

In 2014, opposition candidate Narendra Modi from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the general elections by a landslide and will become the first prime minister to lead a party with an absolute parliamentary majority since 1989. The BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won in 336 out of the 543 constituencies, according to the results the Election Commission of India presented in May 2014. The BJP won an astonishing 282 constituencies, whereas the main opposition party, the Indian National Congress (INC) only won in 44. The results allow Modi and the NDA to form a strong government. Markets reacted to the results with an optimistic surge as Modi’s campaign was centered on deregulation of business and fostering foreign direct investment, a policy setting that he put in place during his time as Chief Minister of the State of Gujarat.

China

For centuries China stood as a leading civilization, outpacing the rest of the world in the arts and sciences, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the country was beset by civil unrest, major famines, military defeats, and foreign occupation. After World War II, the communists under Mao Zedong established an autocratic socialist system that, while ensuring China’s sovereignty, imposed strict controls over everyday life and cost the lives of tens of millions of people.

After 1978, Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping and other leaders focused on market-oriented economic development and by 2000 output had quadrupled. For much of the population, living standards have improved dramatically and the room for personal choice has expanded, yet political controls remain tight. Since the early 1990s, China has increased its global outreach and participation in international organizations.

Since the late 1970s, China has moved from a closed, centrally planned system to a more market-oriented one that plays a major global role, becoming in 2010, the world’s largest exporter. Reforms began with the phasing out of collectivized agriculture, and expanded to include the gradual liberalization of prices, fiscal decentralization, increased autonomy for state enterprises, creation of a diversified banking system, development of stock markets, rapid growth of the private sector, and opening to foreign trade and investment.

China has implemented reforms in a gradualist fashion. In recent years, China has renewed its support for state-owned enterprises in sectors it considers important to economic security, explicitly looking to foster globally competitive national champions. After keeping its currency tightly linked to the U.S. dollar for years, in July 2005 China revalued its currency by 2.1 percent against the U.S. dollar and moved to an exchange rate system that references a basket of currencies. From mid-2005 to late 2008 cumulative appreciation of the renminbi against the U.S. dollar was more than 20 percent, but the exchange rate remained virtually pegged to the dollar from the onset of the global financial crisis until June 2010, when Beijing allowed resumption of a gradual appreciation.

The restructuring of the economy and resulting efficiency gains have contributed to a more than tenfold increase in GDP since 1978. Measured on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis that adjusts for price differences, in 2012, China stood as the second-largest economy in the world after the United States, having surpassed Japan in 2001. The dollar values of China’s agricultural and industrial output each exceed those of the United States. China is also second to the United States in the value of services it produces. Still, per capita income is below the world average.

According to U.S. CIA’s World FactBook,21 the Chinese government faces numerous economic challenges, including:

•Reduction of its high domestic savings rate and correspondingly low domestic demand.

•Sustaining adequate job growth for tens of millions of migrants and new entrants to the work force.

•Reducing corruption and other economic crimes.

•Containing environmental damage and social strife related to the economy’s rapid transformation. Economic development has progressed further in coastal provinces than in the interior, and by 2011 more than 250 million migrant workers and their dependents had relocated to urban areas to find work.

One consequence of population control policy is that China is now one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world. Deterioration in the environment, notably air pollution, soil erosion, and the steady fall of the water table, especially in the North, is another long-term problem. China continues to lose arable land because of erosion and economic development. The Chinese government is seeking to add energy production capacity from sources other than coal and oil, focusing on nuclear and alternative energy development.

In 2010–2011, China faced high inflation resulting largely from its credit-fueled stimulus program. Some tightening measures appear to have controlled inflation, but GDP growth consequently slowed to fewer than 8 percent for 2012. An economic slowdown in Europe contributed to China’s, and is expected to further drag Chinese growth in 2013. In addition, debt overhangs from the stimulus program; particularly among local governments, and a property price bubble currently challenges policy makers. The government’s 12th Five-Year Plan, adopted in March 2011, emphasizes continued economic reforms and the need to increase domestic consumption in order to make the economy less dependent on exports in the future. However, China has made only marginal progress toward these rebalancing goals.

Therefore, China’s competitiveness performance notably has weakened in the past few years. Social sustainability is partially measured for China, as the country does not report data related to youth unemployment or vulnerable employment. However, the available indicators22 show a somewhat negative picture, with rising social inequality and general access to basic services such as improved sanitation remaining low.

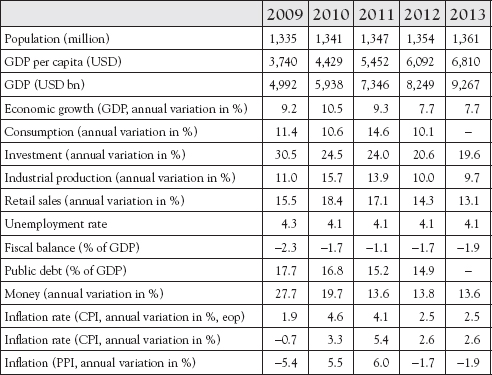

As depicted in Figure 1.5, China’s economic data remains positive. GDP per capita has grown from $3,740 in 2009 to $6,810 in 2013, an increase of over 82 percent (or about 16 percent annually) in just five years. Unemployment has held sturdy at an average of 4.1 percent annually, while public debt has also decreased substantially.

According to the Global Competitiveness Report,* after five years of incremental but steady progress, China has lost some competitive advantages. Without a doubt, the country continues to lead the BRICS economies by a wide margin, ahead of second-placed Brazil, China boasts $8.2 billion in nominal GDP versus Brazil’s $2.4 billion. Although China’s decline is small, its global competitiveness deterioration is more pronounced in those areas that have become critical for China’s competitiveness, namely financial market development, technological readiness, and market efficiency.

For market efficiency, insufficient domestic and foreign competition is of particular concern, as the various barriers to entry appear to be more prevalent and more important than in previous years. On a more positive note, China’s macroeconomic situation remains very favorable, despite a prolonged episode of high inflation. China runs a moderate budget deficit, boasting a low, albeit increasing, and government debt-to-GDP ratio of 26 percent, while its gross savings rate remains above 50 percent of GDP.

The rating of its sovereign debt is significantly better than that of the other BRICS and indeed of many advanced economies. Moreover, China receives relatively high marks when it comes to health and basic education, as enrollment figures for higher education continues to be on the rise, even though the quality of education, in particular the quality of management schools, and the disconnect between educational content and business needs in the country remain important issues.

South Africa

Dutch traders landed at the southern tip of modern day South Africa in 1652 and established a stopover point on the spice route between the Netherlands and the Far East, founding the city of Cape Town. After the British seized the Cape of Good Hope area in 1806, many of the Dutch settlers traveled north to establish their own republics. The discovery of diamonds in 1867 and gold in 1886 stimulated wealth and immigration, while intensifying the subjugation of the native inhabitants. The Dutch traders resisted British invasions but were defeated in the Boer War in 1899–1902. The British and the Afrikaners, as the Dutch traders became known, ruled together beginning in 1910 under the Union of South Africa, which became a republic in 1961 after a whites-only referendum.23 In 1948, the National Party was voted into power and instituted a policy of apartheid, or the separate development of the races, which favored the white minority at the expense of the black majority. The African National Congress (ANC) led the opposition to apartheid and many top ANC leaders, such as Nelson Mandela, spent decades in South Africa’s prisons. Internal protests and insurgency, as well as boycotts by some Western nations and institutions, led to the regime’s eventual willingness to negotiate a peaceful transition to majority rule. The first multi-racial elections in 1994 brought an end to apartheid and ushered in majority rule under an ANC-led government.

Since then, South Africa has struggled to address apartheid-era imbalances in decent housing, education, and health care. ANC squabbling, which has grown in recent years, pinnacled in September 2008 when President Thabo Mbeki resigned, and Kgalema Motlanthe, the party’s General-Secretary, succeeded him as interim president. Jacob Zuma became president after the ANC won general elections in April 2009.

South Africa is a middle-income, emerging market with an abundant supply of natural resources. It has a well-developed financial, legal, communications, energy, and transport sectors and a stock exchange that is the 15th largest in the world. Even though the country has modern infrastructure that support a relatively efficient distribution of goods to major urban centers throughout the region, some factors are delaying growth.

From 1993 until 2013, South Africa GDP growth rate averaged 3.2 percent reaching an all time high of 7.6 percent in March of 1996. The economy began to slowdown in the second half of 2007 due to an electricity crisis. State power supplier Eskom encountered problems with aging plants and meeting electricity demand necessitating load-shedding* cuts in 2007 and 2008 to residents and businesses in the major cities. Since then Eskom has built two new power stations and installed new power demand management programs to improve power grid reliability. Subsequently, the global financial crisis reduced commodity prices and world demand. Consequently, in 2009, South Africa’s GDP fell nearly two percent, to a record low of –6.3 percent in March of 2009, but it has recovered since, at an annualized 0.70 percent in the third quarter of 2013 over the previous quarter.*

South Africa export-based economy is the largest and most developed in Africa. The country is rich in natural resources and is a leading producer of platinum, gold, chromium, and iron. From 2002 to 2008, South Africa grew at an average of 4.5 percent year-on-year, its fastest expansion since the establishment of democracy in 1994. However, in recent years, successive governments have failed to address structural problems such as the widening income inequality gap between rich and poor, low-skilled labor force, high unemployment rate at nearly 25 percent of the work force, deteriorating infrastructure, high corruption, and crime rates.

As a result, since the recession in 2008, South Africa growth has been sluggish and below African average. South Africa’s economic policy has focused on controlling inflation, however, the country has had significant budget deficits that restrict its ability to deal with pressing economic problems. The current government faces growing pressure from special interest groups to use state-owned enterprises to deliver basic services to low-income areas and to increase job growth.

Sub-Saharan Africa has grown impressively over the last 15 years, registering growth rates of over five percent in the past two years, while the region continues to exceed the global average and to exhibit a favorable economic outlook. Indeed, the region has bounced back rapidly from the global economic crisis, when GDP growth dropped to two percent in 2009. These developments highlight its simultaneous resilience and vulnerability to global economic developments, with regional variations. Although growth in sub-Saharan middle-income countries seems to have followed the global slowdown more closely, such as in South Africa, lower-income and oil-exporting countries in the region have been largely unaffected.

As mentioned earlier in this section, South Africa is ranked 52nd in 2013, the best economy in sub-Saharan Africa, and the third among the BRICS economies. The country benefits from the large size of its economy. Particularly impressive is the country’s financial market development, indicating high confidence in South Africa’s financial markets at a time when trust is returning only slowly in many other parts of the world. South Africa also does reasonably well in more complex areas, such as business sophistication, and innovation, benefiting from good scientific research institutions and strong collaboration between universities and the business sector in innovation.

Nonetheless, the 2014 strikes in South Africa have again crippled the economy. The economy contracted 0.6 percent q/q annualized in the March quarter, the first contraction since the 2009 global downturn, and fears have increased of a first-half recession. Year-on-year growth was 1.6 percent. Mining fell an annualized 25 percent, its biggest drop in 47 years. Figure 1.6 provides microeconomic indicators for the country.*

According to WEF’s 2013’s Global Competitiveness report,24 these combined attributes make South Africa the most competitive economy in the African region, but in order to further enhance its competitiveness, the country will need to address some weaknesses. Out of 148 countries surveyed by WEF, South Africa still rank 113th in labor market efficiency, a drop of 18 places from 2012 position, due to its rigid hiring and firing practices, a lack of flexibility in wage determination by companies, and significant tensions in labor-employer relations.

The educational sector is another challenge, as efforts also must be made to increase the university enrollment rate in order to better develop its innovation potential. Combined efforts in these areas will be critical in view of the country’s high unemployment rate of 24.7 percent, although it has improved since 2012, at which time the rate was at 25.7 percent. In addition, South Africa’s infrastructure, although good by sub-Sahara’s standards, requires upgrading. The poor security situation remains another important obstacle to doing business in South Africa. The high business costs of crime and violence and the sense that the police are unable to provide sufficient protection from crime do not contribute to an environment that fosters competitiveness. Another major concern remains the health of the workforce, which WEF* ranked 132nd out of 148 economies, as a result of high rates of communicable diseases and poor health indicators.

BRICS’ Global Influential Ascend

Over the last decade, the BRIC, now BRICS, term has come to symbolize the growing power of the world’s largest emerging economies and their potential impact on the global economic and, increasingly, political order. All five members of BRICS are current members of the United Nations Security Council. Russia and China are permanent members with veto power, while the rest are non-permanent members currently serving on the Council.

Whether the BRICS represents a cohesive group or just a clever acronym, however, is still debatable. Arguably, there are many differences between these countries, from values and economics to political structure and geopolitical interests, which far outweighs commonalities. One main commonality among these countries is a mild anti-Americanism and generally internal or domestic challenge, including but not limited to institutional stability, social inequality, and demographic pressures.

There is a common agreement, however, of how important the BRICS bloc is for each of the members in terms of the symbolism of creating for themselves an important role on the global stage, as well as an alternate perspective on the global economic order, and the desire to wield greater influence over the rules governing international commerce and economic policy. As of 2014, the five nations combined hold less than 15 percent voting rights in both the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), despite the fact their economies are predicted to surpass the G7 economies in size by 2032.

The BRICS, as the biggest emerging markets, are uniting to tackle under-development and currency volatility, as well as pooling foreign-currency reserves to ward off balance of payments or currency crises. The plan calls for an implementation of an institution that encroaches on the roles of the World Bank and IMF. At the time of this writing, the leaders of the BRICS bloc were getting ready to approve the establishment of a new development bank during an annual summit in the eastern South African city of Durban.*

Meanwhile, the IMF seems to be fermenting over the BRICS. After years promoting and showcasing them, in November of 2013 it admitted the bloc had either “exhausted their catch-up growth models, or run into the time-honored problems of supply bottlenecks and bad government.”25 We believe, however, the IMF was caught off guard by the aggressiveness of the emerging market rout when the U.S. Federal Reserve began to reconsider its quantitative easing policies in May 2013, threatening to decrease the dollar liquidity that has fuelled the booms, and masked the woes, in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. This dependence on the dollar has disrupted growth in many regions of the world, especially those more dependent on the U.S. consumer marker and the dollar as a currency.

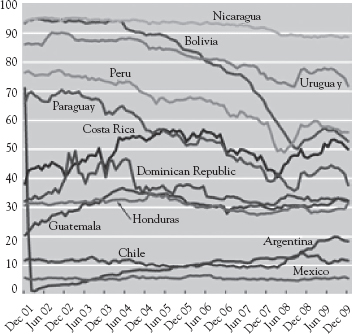

This issue is not new. In the last decade, a few Latin American countries—the most dollarized region in the world—began introducing measures to create incentives to internalize the risks of dollarization, the development of capital markets in local currencies, and de-dollarization of deposits. These all contributed to a decline in credit dollarization globally, but predominantly in Latin America and the BRICS countries. Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay have been gradually declining in financial dollarization.

Coping with De-dollarization

For several decades, dollarization has greatly complicated the policy response in several crises and near-crisis episodes, especially for emerging economies. In some cases, it has been the primary source of financial vulnerability that triggered a crisis not only for BRICS countries, but also for other emerging countries such as the CIVETS and the MENA blocs. The urge to de-dollarize, or to withdraw from U.S. Treasury bills and the dollar, is a direct result of foreign countries’ mistrust in the U.S. government’s ability to control its massive budget deficits. As depicted in Figure 1.7, according to the IMF,26 the degree of dollarization has declined sharply in Latin America over the past decade.

The same trend holds true for other emerging markets around the world. A case in point is Iran. On March 20, 2012, as Iran was celebrating its greatest holiday of the year, New Year’s Eve, it not only celebrated the beginning of a new year but also the end of the dollar as an acceptable currency for payment of its oil.

Although the holiday, known as Nowruz, is typically commemorated by a symbolic purging of the home and spiritual representation of creation and fertility. In 2012, Iran celebrated it by changing its policy for payment of oil. Essentially, Iran made the decision to no longer accept the U.S. dollar as payment for oil, and instead, decided to accept other currencies and commodities.

Figure 1.7 Latin America de-dollarization has been high in the past decade

Source: IMF

Ever since President Obama signed one of the most severe sanction bills against Iran into law, (H.R. 2194), which prohibits any person or business from investing more than 20 million dollars in Iranian petroleum resources, Iran appears determined to phase out the dollar as a form of payment for its oil and derived products. However, if Iran continues to follow through with its decision to refuse dollars-for-oil, it may trigger an intense reaction from the U.S. government, especially for the dollar-reserve currency, mainly supported by the Saud family’s determination to accept only dollars for oil, the so-called petrodollars.

The charter of the Iranian oil bourse, a commodity exchange which opened more than five years ago, calls for the commercialization of petroleum and other byproducts in various currencies other than the U.S. dollar, primarily the euro, the Iranian rial, and a basket of other major (non-U.S.) currencies. While there are three other major U.S. dollar-denominated oil markers in the world (North America’s West Texas Intermediate crude, North Sea Brent Crude, and the UAE Dubai Crude), there are just two major oil bourses: the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) in New York City, and the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) in London and Atlanta.

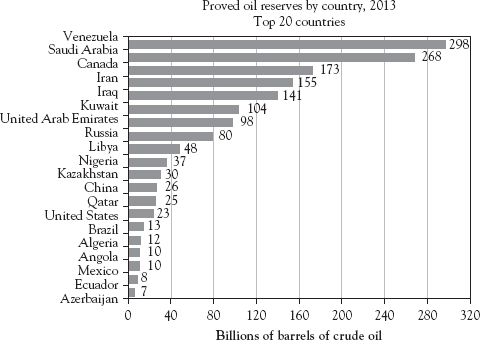

Iran sits on the largest oil and gas reserves in the world, as depicted in Figure 1.8. Consequently, the country has been developing a fourth oil market where U.S. dollars are not accepted for oil trade. In fact, Iran has proposed the creation of a Petrochemical Exporting Countries Forum (PECF), aimed at financial and technological cooperation among members, as well as product pricing and policy making in production issues—not unlike the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The British newspaper, The Guardian, cites Iran, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Russia, Qatar, and Turkey as potential members of PECF.

In the wake of such tensions, India is pondering whether to use gold or yen as payment for oil. India has expanded on this conundrum by proposing the setup of a multilateral non-dollarized bank that would be funded exclusively by emerging nations to include the BRICS countries for the purpose of financing projects in those countries.

Figure 1.8 Iran’s oil reserves is the 4th in the world

The policy debate about de-dollarization, notwithstanding the United States and Iran conflicts, has heated up around the world. Is de-dollarization a realistic goal for the world? If so, how might it be implemented? Can Iran, the BRICS, the CIVETS, ASEAN, and the MENA countries trigger a chain of events that may threaten to crumble the U.S. dollar as the world’s premiere reserve currency? What would be the consequences to the United States, and the world economy, if the dollar was no longer the OPEC measure for oil prices? Certainly, the United States would no longer enjoy the lowest price of gasoline as a non-oil producer nation. The price of fuel would likely skyrocket, increasing the price of all other commodities which ultimately would impact the microeconomics in advanced economies.

While dollarization is a sensible response of economic agents to political or economic uncertainties, its adverse effects often motivate countries, especially emerging economies, to reduce its level. Dollarization is also a rational reaction to interest rate arbitrage opportunities. It may have some benefits, and in extreme cases may be the only viable option available to a country. In such cases, dollarization can be the choice of policymakers or a result of private agents’ decision to stop using the local currency. However, most countries seek to limit the extent of dollarization, owing to its potential adverse effects on macroeconomic policies and financial stability. These include a reduction or loss of control of monetary and exchange rate policy, a loss of seigniorage,* and increased foreign exchange risk in the financial and other sectors.

Often key policies that encourage de-dollarization, especially among the emerging markets, focuses on policymakers’ intentions to gain greater control of monetary policy, often drawing on the experiences of past countries’ successful de-dollarization experiences. We believe durable de-dollarization depends on a credible disinflation plan and targeted microeconomic measures. An effective de-dollarization policy makes the local currency more attractive to local consumers, more than foreign currency. De-dollarization, therefore, entails a mix of macroeconomic and microeconomic policies to enhance the attractiveness of the local currency in economic transactions and to raise awareness of the exchange-risk related costs of dollarization, thus providing incentives to economic agents to de-dollarize voluntarily. It may also include measures to force the use of the domestic currency in tandem with macroeconomic stabilization policies.

On May 16, 2008, Yekaterinburg, Russia hosted the official diplomatic meeting and in June 2009, the BRICS held their first summit in Yekaterinburg. The Yekaterinburg Summit discussions were dominated with negative criticism against the U.S. dollar, with Russion President Putin going so far as to publicly endorse the yuan as a global reserve currency. The group later agreed to replace the U.S. dollar by the IMF’s special drawing rights (SDR).

CitiGroup economists have proposed the idea of the 3-G (Global Growth Generators) countries, comprised of 11 countries’ economies identified as sources of growth potential and of profitable investment opportunities, in an attempt to effectively put an end to the BRICS bloc.27 There is also a geostrategic move to pit India as a linchpin in the Pivot of Asia strategy announced in 2010, intended as a new direction for U.S. foreign and strategic policy in the Asia-Pacific region. It was a policy designed under the assumption that U.S. interventions in other regions were winding down. As Secretary of State, Hilary Clinton noted,

In the last decade, our foreign policy has transitioned from dealing with the post-Cold War peace dividend to demanding commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan. As these wars wind down, we will need to accelerate efforts to pivot to new global realities. … In the next 10 years, we need to be smart and systematic about where we invest time and energy, so that we put ourselves in the best position to sustain our interests, and advance our values. One of the most important tasks of American statecraft over the next decade will therefore be to lock in a substantially increased investment—diplomatic, economic, strategic, and otherwise—in the Asia-Pacific region. … U.S. commitment there is essential. It will help build that architecture and pay dividends for continued American leadership well into this century, just as our post-World War II commitment to building a comprehensive and lasting transatlantic network of institutions and relationships paid off many times over—and continues to do so. The time has come for the U.S. to make a similar investment as a Pacific power, a strategic course set by President Barack Obama from the outset of his administration and one the is already yielding benefits.28

The United States wants to ally with India, Japan, Thailand, South Korea and the Philippines. Could it be that the United States wants to form a sort of Pacific Rim-region alliance, to effectively divide the two prominent BRICS nation, India and China, and effectively generate a global discourse to hedge China from becoming an attractor against American hegemony?

At the moment there is no clear answer. Even academicians have expressed concern about the potential demise of the dollar and the role it plays in global markets, as it guarantees the strength to American society and the military. Joshua Zoffer, staff writer of The Harvard International Review, sums up concerns of a strong BRICS IMF-like development bank and the weakening influence of the dollar in an essay titled Future of Dollar Hegemony:

“As the issuer of the international reserve currency, the U.S. has garnered two unique economic benefits from dollar hegemony. First, in order for other countries to be able to continually accumulate dollar reserves by purchasing dollar-denominated assets, capital has to flow out of the U.S. and goods must flow in. As a result, the value of the dollar must be kept higher than the value of other currencies in order to decrease the price of imported goods. While this arrangement has come at the cost of an ever-growing current account deficit, it has also subsidized US consumption and fueled the growth of the US economy.

The second benefit of this system is its effect on the market for U.S. government debt. The largest market in the world for a single financial asset is the multi-trillion dollar market for American bonds. This market, considered by many to be the most liquid in the world, allows any nation or large investor to park massive amounts of cash into a stable asset with a relatively desirable rate of return. While the depth and stability of U.S. financial markets as a whole were part of the original reason nations gravitated toward the dollar as a reserve currency, the explosive growth of U.S. government debt has made US Treasury bonds the center of the foreign exchange market and the most widely held form of dollar reserves. The use of the U.S. Treasury securities in currency reserves has created an almost unlimited demand for U.S. debt; if the federal government wishes to issue debt, someone will buy it if only as a way to acquire dollar holdings. This artificially high demand means that the U.S. can issue debt at extremely low interest rates, especially relative to its national debt and overall economic profile. And while the U.S. has had to pay off its existing debt by issuing new securities, no nation wants to call in its debt for fear that it would devalue the rest of its dollar holdings. While precarious and arguably dangerous in the long term, the reality is that as long as the dollar is the international reserve currency, the U.S. will have a blank check that no one wants to cash.*

Whether we agree with U.S. fiscal policy, it is indisputable that the ability to finance its debt has allowed the U.S. to provide its citizens with a high standard of living and fund its enormous military programs. Essentially, dollar hegemony has served as the backbone of U.S. primacy.* Domestically, the ability to run effectively unlimited budget deficits has allowed the U.S. to fund its massive entitlement programs and, more recently, afford sweeping bailouts at the height of the recession. The U.S. has used its unlimited allowance, afforded by dollar hegemony, to finance its high standard of living and maintain the prosperity required of a hegemon. More importantly, the U.S. has used the demand for American debt to fund its military apparatus.”29

The BRICS effort to create their own IMF-like bank seems, to address not only a viable alternative for loans aside from the IMF, but also a counter-strategy to fend off advanced economies’ strategies such as 3G and Pivot of Asia, thus reducing their exposure to the dollar-pegged polices.

BRICS Capitalization of an IMF-Like Development Bank

In early 2012, the BRICS countries, together representing 43 percent of the world’s population and 18 percent of the world’s GDP, met in New Delhi, India, for their fourth annual convention. In this meeting of five countries, now attracting more than half of total global financial capital, a plan was announced to establish a BRICS-focused development bank, to be funded solely by BRICS countries. If successful, such bank would enable the bloc to no longer rely on the WB and the IMF for funds, which, for nearly 70 years, have served as omniscient monetary levers for Western interests.

During the G-20 Summit in St. Petersburg, Russia, in September of 2013, the BRICS nations decided to fund their development bank with $100 billion. Russia, Brazil, and India agreed to contribute $18 billion to the BRICS currency reserve pool, while China agreed to contribute $41 billion and South Africa $5 billion.30 The reserves are aimed at financing joint development ventures, and are set to rival the dominance of the World Bank and the IMF. It is unclear if the amount of initial capitalization will exceed the planned seed-capital, as very different sums of money are being mentioned. Nonetheless, assuming the BRICS countries maintain current growth trends, we believe within the next eight years the bloc may have the ability to fund this bank, thus challenging the IMF and Western advanced economies.

The BRICS countries officially announced the formation of the BRICS Bank in their fifth Summit at Durban, South Africa in 2013. The bank was first proposed in 2012 but the proposal was only approved a year later at a BRICS summit in South Africa. According to a Reuters’ article,31 South African Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan indicated that the bloc will have all preparatory work done for setting up its development bank by the group’s next summit in July of 2014.

The group’s other project, a $100 billion fund designated to steady currency markets, has also been off to a slow start, although some progress has been made, which marks an important step to the potential institutionalization of a post-western global order. This is causing a lot of debate around the glove, especially among advanced economies; mainly focusing on whether such bank is viable. In our views, such an event can only be compared to the one in San Francisco, during the Summit of the Allies in 1945, when new institutions were being founded for the post-Second World War world order.

The bloc has struggled to take coordinated action on most issues in the past year after the scaling back of U.S. stimulus prompted an exodus of capital from their markets, but they hope their leaders will officially launch the bank at their July 2014 meeting in Brazil. This IMF-like BRICS development bank, which will focus on funding infrastructure projects without the neo-liberal prescriptions imposed by the World Bank, is funded with an initial capital of $100 billion. Since there is reticence from some of the members to contribute more than $10 billion, China will be the major contributor. China is no stranger to money lending. In 2010 it helped create and fund the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI), a multilateral currency swap arrangement among the ten members of the ASEAN, Japan, and South Korea, which draws from a foreign exchange reserves pool worth $120 billion. That pool expanded to $240 billion in 2012.32 It wouldn’t be surprising if a sudden push for an Asian Monetary Fund was to be developed.

In addition to crafting its own economic and monetary policies, another implication for a BRICS’ “IMF-like” international bank is the possibility of an alternative global currency to the dollar. What would the world prefer: debased fiat money of the Anglo-American led debtor countries or a currency backed by nations whose citizens are enriched with savings and where economies are producing needed goods and services?

Looking back to Bretton Woods, one cannot ignore the massive debt incurred by the U.S. Treasury alone: $16.7 trillion at the time of this writings, and rising. Estimated U.S. population as of summer of 2013 was 316,669,430, so each citizen’s share of this debt is about $52,881.59. The National Debt has continued to increase an average of $1.93 billion per day since September 30, 2012. Conversely, the BRICS have accumulated impressive cumulative reserves topping US$4 trillion. In the short term, this plan is contingent on the extent to which it reconciles the competing agendas of the BRICS nations.

A bank such as this could become attractive for emerging markets, considering the track record of the IMF and World Bank austerity policies in the region, which are very mixed. There is little doubt that many nations would welcome an alternative to these institutions, which would make the BRICS development bank very influential, if we consider the fact that many policymakers believe that the current economic crisis has led to unwielded power of both the World Bank and the IMF, and that this power is uncontested.

There remains the issue of limited IMF and World Bank power. The aftermath of the Asian financial crisis saw a number of countries in Asia and Russia hoarding foreign exchange reserves precisely so they did not have to repay the IMF or World Bank again, or comply with their austerity plans not often prescribed to advanced economies and which resorts to monetization of the debt. The proposed BRICS development bank represents an important new development, that, potentially further circumscribes the influence of those institutions. At least in theory, the BRICS bank could erode the role and status of the IMF and the World Bank. Although it may take a few years before the bank is operational, in the long term this BRICS bank could have a significant impact on the IMF, the World Bank, and global development, as the bank would have access to a vast and growing emerging market. We caution though that the power struggle between nations could lead to difficulties.

At present, China holds vast foreign exchange reserves and is likely to play a major role in the BRICS bank. South Africa, with the weakest economy among the BRICS, due to increased reliance on minerals prone for eventual depletion, may have the most to gain from the establishment of the bank. Nevertheless, we believe the entire BRICS bloc could benefit from the international clout the new bank would wield.

Meanwhile, American politicians plan on increasing the U.S. debt even further by at least $1 trillion a year into the foreseeable future—the stock market rebounds every time the Federal Reserve Bank suggests the potential for more stimulus—the European sovereign debt crisis is an ongoing financial crisis that has made it nearly impossible for some countries in the eurozone to refinance their government debt. During the early summer of 2012, Spain’s borrowing costs skyrocketed to seven percent yield on the 10-year bond after Moody’s downgraded its bond rating. As of summer 2013, yield fell to five percent, as a result of ECB backstop, but we don’t believe it to be sustainable. Spain’s borrowings costs will likely continue to rise as a result of the U.S.’s own challenges in jumpstarting its economy.

Also in summer of 2013, Italy, too, is struggling to sell its bonds, being forced to pay the most in nearly a year to sell three-year paper at auction. Italian debt has underperformed that of Spain due to political turmoil involving its former premier Silvio Berlusconi whose outcomes could bring down the Italian government.

A bias we could not avoid during the research of this book is that we are avid believer in a free-market system. Hence, we also believe government programs and monetary stimulus tend, all too often, to be a waste of money. Every policy, rule, and regulation sponsored by government and imposed onto its citizens—i.e. printing of fiat money throughout most of the advanced economies—appears to be a type of price fixing; in this case, to promote currency debasement. In the long run such strategies simply aren’t sustainable. It only degrades society’s wealth and over time pools more and more of society’s assets into the hands of unscrupulous leaders and financiers. Inevitably, the printing press creates an overabundance of money, which in turn makes people feel rich and overspend, creating yet another (false!) boom that will lead to another real bubble. Eventually the bubble bursts, turns to a bust and the cycle repeats itself.