Project Team Leadership

An Introduction to Project Team Leadership

An Introduction to Project Team Leadership

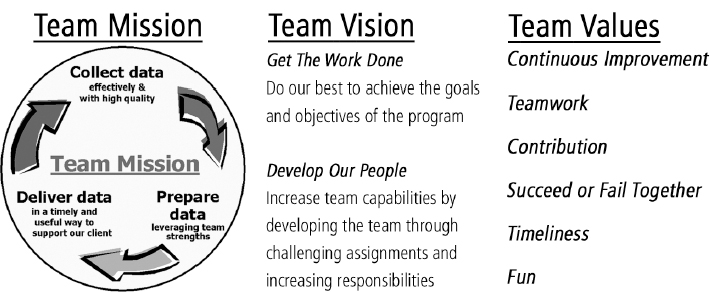

Project team leadership is the overarching aspect of the emotional intelligence framework for PMs. It is about getting the right people on your team, successfully communicating with and motivating them, and then clearing conflicts and other roadblocks so that they perform and achieve the project objectives. This domain includes the project management competencies of communications, conflict management, and inspirational leadership, as shown in Figure 7-1.

Like the relationship management domain that we explored in Chapter 6, project team leadership builds on the previous emotional intelligence domains.

What the Experts Say About Team Leadership

Though leading teams is critical to PMs, emotional intelligence researchers have only indirectly tackled the subject. Daniel Goleman and his Primal Leadership coauthors looked at the various emotional intelligence competencies and how they impact leaders. (Primal Leadership also discusses six leadership styles that we explore in Chapter 8). Otherwise, little information is available to relate emotional intelligence to the leadership of project teams.

As noted in Chapter 7, I chose to designate several of the competencies that Goleman included under relationship management as team leadership competencies. Communications is a core competency for both project management and emotional intelligence. This includes not only empathetic listening, as discussed in Chapter 4, but also consistent and effective communicating with project stakeholders.

Figure 7-1: EQ Model Showing Team Leadership.

Conflict management is the second competency that we will explore. This is another subject that should be very familiar to PMs. Goleman views conflict management as negotiating and resolving disagreements; it includes the following competencies:

• Handling difficult people and tense situations with diplomacy and tact

• Spotting potential conflicts, bringing disagreements into the open, and helping to de-escalate

• Encouraging debate and open discussion

• Orchestrating win–win solutions1

Finally, we will look at what Goleman alternatively calls leadership or inspirational leadership. In Working with Emotional Intelligence, Goleman defines leadership as inspiring and guiding individuals and groups and includes the following aspects of leadership:

• Articulating and arousing enthusiasm for a shared vision and mission

• Stepping forward to lead as needed; regardless of position

• Guiding the performance of others while holding them accountable

• Leading by example2

Communications

Communications

Undoubtedly PMs need to be great communicators. This is one of the most important skills that a PM should possess. It is hard to imagine a successful PM who is not a good communicator.

Not everyone appreciates the need for PMs to be great communicators. It is entertaining to hear the criticism of PMs by team members who are new to projects. I have heard quite frequently that “All you project managers do is walk around and talk to people.” I wholeheartedly agree with that statement. Walking around and talking to people is one of the important ways that PMs communicate. Unfortunately, the individuals who make those types of statements haven’t yet seen the value in good communications.

I am also entertained when I hear the following from a new team lead or PM: “I didn’t get anything done today; all I did was sit in meetings.” This is typical of new PMs who were accustomed to being individual contributors. Frequently, they will feel frustrated with their apparent lack of contribution and the fact they were in so many meetings. To them I say, “Welcome to project management.”

The reality is that for most PMs, a big part of the job is communications. That may take the form of walking around and talking with team members or stakeholders. It may also mean sitting in lots of meetings. That is communications. Communications can also include talking on the telephone, writing emails and instant messages, preparing for meetings, creating and delivering briefings, and generating status reports.

This section focuses on how to apply emotional intelligence to improve project communications. Project communications are a rather broad topic and some level of familiarity with the topic is assumed. For PMs who are not familiar with project communications, I recommend that you start with Chapter 10 of the PMBOK® Guide, which is dedicated to this topic.

Of course, the PMBOK® Guide does not address the application of emotional intelligence to communications. For best results, we need to consider our own emotions, the emotional content of our messages, and the emotions of the recipients of our communications. In the next section, we look at how PMs can leverage emotional intelligence to improve communications with team members and other stakeholders. Then we look at specific types of communications methods, the advantages and disadvantages of each, and ways to improve them with emotional intelligence.

Communicating with Emotional Intelligence

No matter what form they take, communications contain and evoke emotions. Well-planned communications, therefore, help the PM set the emotional tone for the team. Poorly executed communications can trigger negative emotions in the team.

Communicating with emotional intelligence involves applying the domains of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management. PMs who are competent in each of those domains will do a better job of communicating with emotional intelligence.

If you want to be intentional about your project communications, consider the following steps:

• Determine your objective.

• Understand your own emotions.

• Choose an appropriate time, place, and mode.

• Approach others with empathy.

• Listen and respond to the emotions of others, and not only to the content of what they say.

• Share your own emotions when appropriate, being as open and honest as possible.

• Check for understanding and reactions.

Determine Your Objective

Determine your objective means to understand the point of the communications. Some examples of communication objectives include:

• Recognizing the work of others.

• Encouraging or motivating team members to work harder.

• Providing constructive feedback to encourage someone to change their behavior.

The key is to be clear about our objectives up front. If we don’t set realistic objectives before we communicate, we are not likely to be clear, concise, and consistent and probably won’t achieve much.

I have found it helpful to jot down a few bullet points before important meetings. These bullet points might be in addition to an agenda or any other preparation I would do for the meeting. I would typically choose my words carefully since I understand that word choices can affect the emotions evoked.

Understand Your Own Emotions

Understanding our own emotions means we are aware of our emotions or self-aware, as we learned in Chapter 3. This is a necessary first step for good communications. If we are unaware, we won’t be able to accurately communicate with others on an emotional level. Our own emotional state will leak out in undesired ways, or we will misrepresent how we feel to others. We should start by using the SASHET model introduced earlier to be clear about our own emotions.

Choose an Appropriate Time, Place, and Mode

It is critical that we choose an appropriate time and place for our communications with others. Delivering bad news at the end of the day when your team is heading out the door is poor timing. Even worse timing would be to deliver bad news when you are leaving the office early and won’t be around the rest of the day. You need to be careful, though, that you don’t stall on delivering news because “the time isn’t right.” While timing is important, we should not let our own fear cause us to delay the delivery of bad news.

It is also imperative that you choose an appropriate place for the communications. Privacy is critical when discussing personal issues.

I once had a situation with a team member who had failed to meet an important deadline. I made the mistake of addressing the issue with the team member in his cubicle, which was part of the open landscaping in the office. Needless to say, it was inappropriate to discuss this person’s shortcomings when others could hear the conversation.

Finally, we need to consider the modes of communications that are appropriate in any given situation. It would not be appropriate to use a fax message to fire someone. Nor would it be appropriate to use instant messaging for a tough discussion. Both of these situations would be well served by a face-to-face discussion.

There are also times when we need to use multiple modes of communication. Often, our verbal discussions will need to be supported by a written communication or some other form of documentation to keep in our permanent records.

Approach Others with Empathy

Where possible we must approach others with empathy. We should attempt to think through how they will feel before and after our communications with them. For example, consider if the other party or parties will be scared in anticipation of bad news. Think about how we expect them to feel after we deliver our message. Do we expect them to be happy after we recognize their performance? What will we need to do in order to assure that they take this in the most positive light?

Listen and Respond to the Emotions of Others

As project leaders, we need to distinguish between the content of what people say and the emotions underneath that content. In many situations, it is more appropriate to respond to the emotions than to the actual words that the individual is saying. As an example, we may say something like “you sound disappointed.” We may need to lead others to appreciate what they are feeling and help them to articulate that. This includes listening with empathy and using paraphrasing or other playback methods to replay what we hear from others, as we discussed in Chapter 4.

Share Your Own Emotions When Appropriate

We also need to be able to share our own emotions when appropriate. We should strive to be as open and honest as possible. Of course, this doesn’t mean that we bare our souls and share everything.

We may also want to practice the truth-telling techniques that we learned in Chapter 6. This may not be appropriate in all situations. Use your emotions to guide you in determining how much to share. Consider your objective for the communication and evaluate whether sharing additional information will bring you closer to that objective.

Check for Understanding and Reactions

Just because we delivered a message in a meeting doesn’t mean that the recipient understood or retained the message. We need to follow-up with receivers to make sure that they understand what was communicated. We might also ask for their reaction to the message.

I like to leverage key project team members to check for understanding and reactions. In nearly every project team that I was on, there were a couple of team members who could be trusted to be open and candid about their reactions. I would seek them out after important meetings to see what they heard, what they took away, and any reaction they might have had to the message.

Methods of Project Communications

Methods of Project Communications

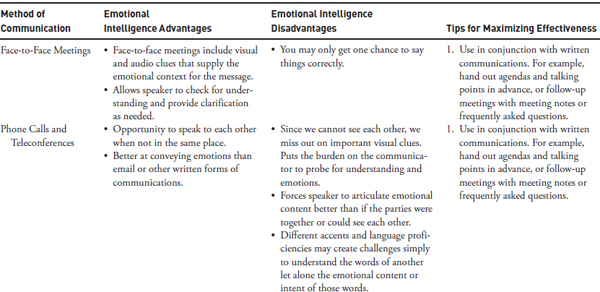

Table 7-1 provides a summary of some popular modes of communications that a PM may use, the emotional intelligence advantages and disadvantages of each, and some tips for applying emotional intelligence to each mode.

Use Email and IM Carefully

A word of caution about the use of email and instant messaging (IM) as communication tools. Each of these has its place on project teams. Email has been used for several years to support project communications. In recent years, IM has rapidly become accepted as a valuable project communications tool. It is the power of these two modes of communication that can make them risky if not used properly.

With email, you can reach a very wide audience in a hurry. This is great if there are important and urgent communications that need to go to that wide audience. It is not so great if you have lost control of your emotions and you want to vent to everyone about how angry you are.

You may not even do this intentionally. I have inadvertently sent email messages to the wrong recipients on multiple occasions. This is especially embarrassing if the message is poorly written, unprofessional, or has a critical tone. More important than proper addressing of emails is to think before you even create the message. Go back to the steps we mentioned in this section and think about your objectives and your feelings. Before creating an email, make sure that you need to send one. If you are responding emotionally, email is unlikely to be the best mode of communication.

Instant messaging has similar shortcomings though it doesn’t necessarily have the power to communicate the same message to multiple people at the same time. Many people use IM to keep ongoing informal chats going throughout their day as they work on different tasks. These individuals may have three or four different conversations going on at the same time. (I find myself challenged to have one meaningful conversation at a time.) Those who have several conversations going run the risk of sending the message to the wrong recipient.

Table 7-1

Another risk with instant messaging is the apparent informality. The ability to chat back and forth can cause people to become less professional, or even flirtatious, or to act in otherwise inappropriate ways. It seems that every year there are scandals involving public officials and celebrities whose inappropriate texts and photos were made public.

Both email and IM suffer from a lack of context. The same message can be interpreted multiple ways. Without visual clues it might be hard to tell if someone is joking around or if they are angry and serious. Two people may read the same message and come away with a different interpretation of the message.

Improving Your Meetings

Most project team members seem to dislike the deluge of meetings that come with the job. Here are some ways to improve your meetings to make them both worth attending and enjoyable.

• Start with meeting objectives and an agenda.

• Monitor the group for emotions and aliveness. If everyone seems angry or bored, it may be appropriate to state that you’ve noticed this and ask why.

• Always show respect for others, in particular those not present.

• Monitor and address sarcasm and other inappropriate expressions of emotions.

• Address conflict.

• Lead with your own emotions.

Nonverbal Communications

The focus of the previous section has been on verbal communications. It is important to recognize that we communicate all the time without using words. Nonverbal communications can include body language, touch, the artifacts and items found in your office, your own physical appearance and dress, the actions you take, and even the car you drive. Each of these things sends a message about you even before you open your mouth or write something.

The most important nonverbal communication is actions. It has been said that actions speak louder than words. The actions you take, or the ones you do not take, send messages more clearly than if you had spoken the words. If your words do not match your actions, people will be more likely to pay attention to your actions than your words. As the next section describes, we need to be consistent in all of our communications.

Congruence in Communications

Congruence is a principle that applies to all of the ways in which we communicate. We need to be consistent in the message that we send with our words and our actions. We cannot tell someone they are important to us and to the team and then act in ways that send a different message.

Today’s reality TV shows provide plenty of examples of nonverbal communications. Look for examples of people who are saying positive things, yet glaring at others, avoiding eye contact, or even rolling their eyes. Look for those who smile when they say they are angry, or who are clearly acting angry yet pretending not to be.

Congruence in our communications also means that we are consistent with our actions and words with different groups of people, both inside and outside the company.

Conflict Management

Conflict Management

Conflict Is Inevitable

Conflict seems to be inevitable on projects. From the start, projects are built on a foundation of the conflicting constraints of time, cost, and scope. Further, projects are often created to satisfy the needs of one set of stakeholders, which may be at odds with needs of other stakeholders. During the execution of projects, conflict frequently surfaces over contention for resources, rewards and recognition, roles and responsibilities, team member diversity, technical decisions, reporting structures, and, even, individual personalities.

Lack of emotional intelligence in project team members and stakeholders can also cause conflict. Team members and stakeholders who experience emotional breakdowns or lack emotional self-control are like ticking time bombs. When these bombs detonate, they will frequently take healthy members of the team with them, which could include you as the PM. Even team members and stakeholders with high emotional intelligence may create conflict with others when they are under stress and pressure.

Project conflict can be disruptive. If not properly channeled, conflict can stifle communication, kill creativity, and squash productivity. Unmanaged conflict will create unnecessary distractions and may encourage otherwise good resources to leave the team. Project teams that are not able to manage conflict may ultimately fail to reach their objectives.

Conflict May Be Healthy

In some cases, conflict is healthy. Properly managed project conflict can galvanize teams, spark creativity, and cause healthy competition. Project conflict is an opportunity for the PM to demonstrate leadership with emotional intelligence competencies, such as empathy, self-control, and relationship management.

Conflict Management Is the PM’s Job

Conflict management is an essential part of the PM’s job. The PM is the one who will make the difference between leveraging conflict and having conflict wreak havoc on the team. Successfully recognizing and addressing conflict is part of the PM’s role.

Recognizing That We Have a Conflict

The first step in the process is to recognize that there is conflict. In many cases, it won’t be difficult to see. Consider the case where a team member said to me, “I won’t work for him anymore,” and then proceeded to tell me about all the shortcomings of this team leader and how hurt she felt.

In another example, two subteams were involved in a decision over two possible technical directions. One team lead calmly described the two approaches, their relative merits, and the shortcomings of each. The other team lead simply said, “Any idiot can see that this is the only valid approach.”

It is not hard to see the conflict in these examples. It would not be hard if we saw or heard two individuals arguing with each other. However, the signals may not always be this clear. We need to be attuned to our environment to pick up on subtle signs that something is wrong. These signs include lack of communications, missed deadlines, poor quality deliverables, or deliverables behind schedule. Team members may reflect the conflict in their communications through sarcasm or the silent treatment. They may also do everything possible to make life difficult for other members, or avoid all meetings.

Traditional Approaches to Conflict Management

Assuming that we do recognize project conflict, how do we go about managing it? We can start with the five traditional ways managers have addressed conflicts. These modes, outlined in Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling, are:

• Smoothing (or accommodating)

• Forcing

• Avoiding (or withdrawing)

• Confronting (or collaborating)3

Let’s look at each of these classic modes of conflict resolution from an emotionally intelligent PM perspective.

Compromising

Compromising is when we search for a solution to the conflict that splits the difference and brings some degree of satisfaction to each party. Compromising is characterized by give-and-take from each of the affected parties. PMs who compromise are not necessarily looking for the best solution; they are simply looking for a middle ground that will be acceptable to both parties.

Compromising takes more emotional intelligence than withdrawing or smoothing because the issue is brought out into the open and discussed. However, compromising doesn’t allow for the possibility of a win–win solution. It requires each of the parties in the conflict to give up something. It may encourage tentativeness in team members rather than going all out.

Compromising may be useful when the stakes are not very high and when both parties want to maintain the relationship.

Smoothing or Accommodating

Smoothing is when we minimize or avoid areas of difference. Smoothing managers tend to talk others out of being upset or try to gloss over it by emphasizing areas of agreement. They may establish a subteam to tackle a tough issue to reduce polarization of the team and avoid win–lose thinking.

A classic example of smoothing would be the plea, “Can we get along here? Can we all get along?” That comment was made by police assault victim Rodney King after the 1992 Los Angeles riots. King was trying to smooth over the areas of upset and disagreement and urge people to just get along.

As a technique for resolving project conflict, smoothing is relatively low in terms of emotional intelligence. Like withdrawal, when we use smoothing we are not dealing with the underlying issue that is causing the conflict. Instead, we are avoiding the issue.

Smoothing can often cause problems to fester and reappear in other ways. PMs who smooth over conflict force team members to take their issues underground. They will often vent their concerns to others and thereby sow dissention. Team members who are encouraged to smooth over conflict may begin to downplay or withhold bad news. The message they receive from the PM is, do not rock the boat.

We can use smoothing when the stakes are not very high or when we want to maintain good working relationships. Otherwise, it should be avoided.

Forcing

Forcing or suppression is used by managers who see conflict as disruptive to team productivity and try to squelch that conflict. The manager makes it clear that disagreement is not tolerated and will work quickly to deal with any conflict. Any challenge to the manager is viewed as subordination. It is often characterized by a win–lose feeling in the team.

Forcing does not examine and address the underlying cause of the conflict and so is likely to lead to a recurrence of the problem in another form. The PM’s intolerance stifles any real discussion of the conflict and extinguishes the possibility for learning and change.

As you might imagine, forcing takes very little emotional intelligence. The parties involved may see a particular conflict as one in a series of conflicts. Each may feel that if they lose this one conflict, they can even things up later. After a conflict is resolved, the two parties may simply be regrouping and preparing for the next battle.

Forcing is a shortsighted approach to conflict resolution. It should be used only when time is limited, when the long-term relationship is not important, or when no other solution will resolve the situation.

Avoiding or Withdrawing

PMs who use withdrawal will retreat from an actual or potential disagreement. They avoid disagreeing with others. They may go so far as to physically separate themselves from conflict by leaving the room or even taking a vacation. They may also distance themselves from unpopular management decisions saying, “Hey, I am just following orders.”

In relation to the other approaches, withdrawal is very low in terms of emotional intelligence. In fact, withdrawal was identified as one of the emotional breakdowns described in Chapter 4. When we use withdrawal to deal with a conflict, we are disengaging from the relationship. We don’t tell the truth about our feelings or our wants and needs.

As you might expect, withdrawal does not solve anything. In fact, with withdrawal we don’t even acknowledge that there is a conflict. When we use withdrawal, we aren’t really interested in solving the problem. We don’t provide the other party the opportunity to work with us to resolve the conflict.

Withdrawal can be successful as a short-term strategy. By separating parties in a dispute, we allow the air to clear and cooler heads to prevail. Withdrawal would be very appropriate in situations where you believe that there is a risk of physical danger to anyone. Withdrawal could also be useful in situations where there is no long-term relationship. If you experience conflict in the last few weeks of a project, you may decide it is not worth working to resolve that particular issue. In all other cases, withdrawal should be avoided.

Confronting or Collaborating

Confrontation is facing the conflict directly and using problem-solving techniques to work through the disagreement. When we use confrontation, we bring the conflict out into the open so that we can deal with it. Confrontation is what is often described as seeking a win–win solution. Confrontation is the one technique that addresses the underlying cause of the conflict, making it the most economical solutions in terms of personal investment and return.

As you might guess, confrontation is the highest in emotional intelligence of all the conflict resolution approaches. It takes a PM with emotional intelligence (and courage) to confront conflict directly and work to resolve it. PMs may feel scared or inadequate to deal with the conflict.

I was taught an important but embarrassing lesson about using confrontation to resolve conflict. Several years ago, I was a co-test manager partnering with another manager to complete testing for a large systems integration project. I found working with the other manager difficult. I was organized and had experience with test planning and execution. My fellow manager was experienced with the technology we were using but lacked the skills to organize and execute the testing. I became frustrated. After some half-hearted attempts to talk to my coworker, I told the project director that I had an issue with my co-test manager. His response was to invite me to meet him for lunch that very day.

When I arrived at the restaurant, I was surprised to see the project director sitting in a cozy round booth with my co-test manager. I sat down with the two of them and immediately the project director asked me what it was about my co-test manager that I needed to discuss with him. I was embarrassed, to say the least.

The confrontation with the project director taught me a few things. I learned that I should have spent more time working on the issue with my co-test manager before bringing it to the project director. I learned that the reason the project director paired us up was exactly the issue I wanted to complain about—we had different strengths and skills sets. Most important, I learned that the most direct way to resolve an issue was to confront it directly.

I try to remember these lessons when individuals come to me with issues or conflicts on a project. I try to tell them that the shortest distance between two people is a straight line and that is the most direct way to resolve a conflict.

One final note about confrontation. It is important for PMs to send the message to their team that they are open to confrontation themselves. You want your team to be comfortable bringing issues with you out in the open without fearing reprisal.

Applying Emotional Intelligence to Conflict Resolution

Beyond looking at the levels of emotional intelligence in each of the conflict resolution approaches, we can also use the emotional intelligence competencies to better manage conflicts. We begin with a focus on what each party is feeling.

Conflicts involve both facts and feelings. It is usually easy to get the facts. That is the “he said, she said” part of the transaction. The facts are helpful as a starting point, but they are only part of the story. We need to get beyond the facts to understand why those facts matter so much to the parties involved. That requires an understanding of the underlying feelings as well as the unstated wants and needs of each of the parties.

It is important to probe to find out what the parties in a conflict are feeling. We need to listen emphatically and pay attention to feeling words and body language. We may even need to ask questions. Recall the example described in Chapter 5 where a team member sat with her arms crossed, fiercely insisting “I am not angry.” People in conflict usually feel scared, angry, sad, or some combination of all of these things. They may be angry about critical remarks from a coworker. At the same time, they may be sad because their feelings are hurt and they want to be friends with the coworker who made the remarks. Finally, they may be scared of a confrontation or scared that they need to leave the project because of that person.

It would be unlikely that a team member involved in a conflict would have the emotional intelligence to openly discuss the full range of emotions that they are feeling. More often, individuals will not be aware of the various mix of feelings they are experiencing. The PM can lead or coax team members to appreciate the different feelings they are experiencing.

Understanding the feeling is the first step. The second step is to identify the underlying want or need. Some common wants and needs of project stakeholders are shown below:

• Want to be important

• Want to be productive

• Want to be promoted

• Want to feel part of the community

• Need to make more money

• Need to express themselves

• Need to be liked or loved

When we understand the underlying wants and needs of the affected parties, we better understand their motivation. Then we can work together to address the issue or conflict that is caused by the underlying want and need. We can help each party to the conflict understand the wants and needs of the other party and to achieve their own wants and needs.

You Might Just Be the Cause

Our approach may vary a little if we are a part of the conflict or the cause of the conflict. If we are part of the conflict, we need to first orient to ourselves. The questions that we need to ask remain the same. We need to understand what it is that we are feeling. We will typically be sad, angry, or scared. We go further by asking what it is that we are sad, angry or scared about. What is our underlying want or need in this situation? How does this conflict move us closer to or further from our wants and needs?

Once we understand where we are coming from, we can evaluate the other person. We start by trying to understand what they are feeling. Then we explore what they want and need in this situation. Then we explore ways to work with them through the conflict. We may want to think it through on our own and then discuss it with the other party. If it is tense or uncomfortable with just the two of you, ask for a peer manager or for a neutral third party to join the discussion.

Calmly leading others through conflict can help strengthen our relationships and build the team. It is also a way for PMs to demonstrate leadership.

Inspirational Leadership

Inspirational Leadership

The third and final competency of team leadership is inspirational leadership. This is the ability to inspire others by casting a vision for the individual and the team. PMs who are inspirational leaders make work attractive and interesting to the team, create high team morale, and attract and retain good resources.

In the movie, As Good as it Gets, Jack Nicholson plays a gifted writer named Melvin Udall who has a lot of emotional issues. He is a good example of someone with low emotional intelligence. One of my favorite moments is when Melvin Udall dines with Carol Connelly, played by Helen Hunt. After Melvin makes one of his typical harsh and narcissistic comments, Carol demands that he give her a compliment right now. It takes a few moments for Melvin to respond, but the words he says have become one of the best known movie lines of all time. Melvin says, “You make me want to be a better man.”

The lesson here is that as much as we might try, we cannot force anyone to do anything. Very few PMs have the ability to hire and fire. So to get things done, we need to make people want to do them. We need to inspire them, so much so that we “make them want to be better team members.”

Vision Casting

Vision casting is the process of stating a future, positive picture of the goals or objectives for the team, assisting the team to understand why they are important, and helping the team to connect with those goals and objectives. Vision casting for projects is the responsibility of the PM.

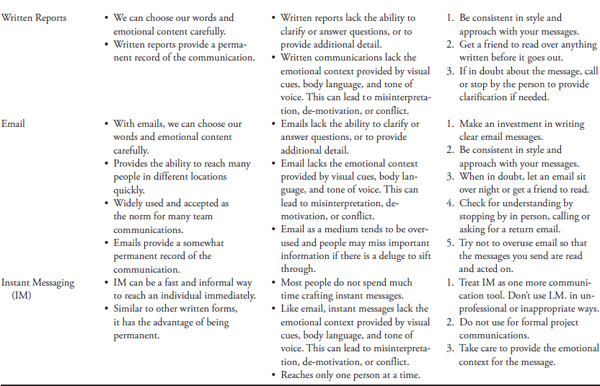

One way to cast a vision is through the use of the mission, vision, and values statement for the project or team. The mission is a short statement about the overall objective for the team or what is going to be accomplished. The vision is a statement on how that mission will be accomplished. And the team values are the framework for pursuing the mission.

Consider the following example from a recent project that I managed. I created the picture shown in Figure 7-2 to represent the mission, vision, and values for the team.

The articulation of the team mission had a galvanizing effect on the team and on me as the leader. When I began to leverage this statement, it anchored my decisions and helped me show others how their work fit into the larger picture. Each part of the mission, vision, and values statement was applicable. For example, I used the mission to help communicate the priorities for everyone on the team. Up to that point, each subteam had focused only on its own part of the project and its own work. The diagrams and words reminded them of the goals of the larger team. The vision was also important, as it showed the balance I was striving to achieve between reaching the stated project objectives as well as investing and growing the people.

Finally, the values were important since they served as ground rules or the code of conduct for the team. We developed the values list by team vote. Once we agreed to certain values, we used them to set a framework for how we would operate.

Figure 7-2: Example of Mission, Vision, and Values Statement.

The biggest impact of the mission, vision, and values statement was that the entire team could understand what we were doing and how their particular part fit into that mission. They also began to appreciate my goals for how we would get the work done and how that would benefit them individually.

Additional Considerations for Team Leaders

Additional Considerations for Team Leaders

Building the Project Team

One of the important roles of the project team leader is to build the project team. This includes selecting the best team members, taking steps to retain them, and removing resources from the team when necessary. As stated in Chapter 1, as a PM, you live or die by your resources. The skills, experience, and motivation of the resources will determine what can be accomplished by the team. It is essential that you get the right team and that you are able to retain them until the project is over.

Selecting Project Team Members

Of course we don’t always have the luxury of selecting our team members. But, usually, we have some latitude when it comes to choosing who will be on the team. We need to exercise all the power we do have to maximize our chances of success.

Selecting the right team members from the beginning is very important. Many PMs act as if they have little or no say over their resources or that their choices don’t matter much. Both of these attitudes stand in the way of getting the best resources for your teams. Resources are unique; they are not generic or interchangeable. Consider the fact that on IT projects, the best developers outperform the worst developers by a factor of 10 to 1.

Professional sports teams are in the business of trying to win. They take recruiting talent very seriously. Look at how professional sports teams address the draft. They understand the importance of identifying the strengths and weaknesses of their current teams and finding new players who will fill the gaps and round out the teams. A professional football team doesn’t just think linebacker, kicker, or center. Each looks deeper to get just the right skills to complete the entire team. PMs could take a page out of the NFL playbook when it comes to recruiting resources for the teams.

What kinds of factors go into the decision to hire resources? Most people would consider the candidates’ technical capabilities, skills, and experience as the key factors. Here are some additional factors that I think need to be considered:

• The strengths and weaknesses of the candidate versus the strengths and weaknesses of the team

• The candidate’s experience with similar projects (size, technology, client)

• The candidate’s attitude toward the project and team

• The candidate’s personality and fit with the rest of the team

• The candidate’s level of emotional intelligence

Of course it will be difficult to assess several of these factors in an interview, including the candidate’s level of emotional intelligence. The point is to think beyond the basic questions of skill or experience and begin to look at the dynamics of the team and how each person will fit.

This list even mentions attitude. A good attitude is just as important as having the correct skill sets for the project. I have heard leaders say they hire for attitude and train for particular skills.

Different projects will require different approaches. I once managed a very large project that required hiring a lot of resources. I noticed that we had problems with those resources who up to that point had worked only on relatively small projects. Those resources had a difficult time dealing with certain big project issues, such as bureaucracy, recognition, and collaboration. Over time I learned to ask an additional question during interviews and that was, “What was the largest project team you’ve worked on?” I began to exclude those people who had worked on teams of only five or six people because they often did not perform well on a team of thirty or fifty members.

The goal of the PM when selecting resources is to add to the overall team capabilities. We want to select the individuals who will fill gaps, add to the team strengths, and generally bolster the team.

Better Decisions Through Emotional Intelligence

One of the ways in which project leaders can leverage emotional intelligence is making decisions. We talked in Chapter 1 about emotions being information and how that information is like personal radar. This section discusses how to leverage that emotional information to make better decisions.

Negative emotions should be monitored closely during decision making. In Chapter 3, we talked about how our emotions can lead us to make poor decisions or to react without thinking, resulting in emotional breakdowns. We can make terrible decisions if we let ourselves be swayed by fear, sadness, or anger without looking at the cause of those negative emotions. When we recognize those emotions, however, we can look beyond the feeling to the underlying cause. This will allow us to take in the emotion and any other issues and reframe the decision to include a full view of the situation.

In fact, David Caruso and Peter Salovey argue that each of the emotions serve us differently for different types of decisions. Their research shows that people in a sad mood can often develop more persuasive messages and better-quality arguments than people in a happy mood. Conversely, people in a happy mood may have more creative arguments than those who are sad.4

Which makes sense, because when we are sad or scared, we tend to be overly pessimistic. We have a hard time seeing that something is working, and we pick apart a plan and find all its faults. We are more likely to say no even when it might serve us better to say yes.

Ironically, individuals who are in positive moods can also make some very poor decisions. They will tend to underestimate the risk of negative events. When we feel happy, we may overlook key information, neglect to plan for contingencies, or gloss over negative data. We may be overly optimistic about project outcomes and fail to consider relevant risks. We may say yes to additional work or deliverables when we should say no.

Anger is a powerful emotion that helps motivate us to act. Anger can give us the power we need to make important changes or to simply get us moving when we are scared.

The starting point, then, for using emotions as input to decisions is to understand what we are feeling and, as noted in Chapter 3, to understand as much as possible why we are feeling that way. That understanding should lead to using our underlying emotions to balance our decisions. We need to understand what our gut feeling is telling us. If we feel uneasy about the interview with the candidate for the open developer position, what is behind that feeling? Armed with that information, we can approach a decision differently.

The second part of decision making with emotional intelligence is to understand and incorporate the feelings of those around us. What do others feel about this decision or the underlying issues? What is their position and why? This is where we use our social awareness skills to understand others. We can use our empathy to put ourselves in their shoes and identify what they are likely to feel. For individuals we know well, we can use our understanding of their typical emotional state. If others tend to be overly happy or sad, that might influence the way they evaluate a particular situation.

Once we understand the emotional landscape, we can look past the emotions to the principles involved. We orient to principles when we make a decision that is grounded in the values of the team and the organization. We may be scared about a decision to bring on a new resource or try a new technology on the project but we need to see past the fear and look at the benefits we are trying to obtain. We need to make the best decision at the time in spite of how we might feel.

Getting Support

My mentor Rich has often said that big goals require big support. If we are going to live big as PMs and leaders, we need a lot of support. A good metaphor for support is the great pyramids. Think of the pyramids and the size of the base relative to the height of the peak. The higher the pyramid, the larger the base needs to be, as shown in Figure 7-3.

Figure 7-3: Support Base for a Pyramid.

So what is support? In this context, it means the emotional support and help of others. It could be help in the form of encouragement, accountability, listening, feedback, or coaching and mentoring.

Getting support is a relatively new concept for me, as it may be for many PMs. I used to be the type who got it all done on my own. I was independent. I rarely asked others for help and saw it as a weakness if I did.

I’ve come a long way in this area. I have participated in men’s groups that provide emotional support for husbands, fathers, and business leaders. I’ve participated in several running groups that helped me qualify for the Boston Marathon. I’ve attended personal growth retreats at least once a year—and sometimes more—every year since 2001. This book actually sprang from my work with three different mentors, and I am honored to have different people involved in reviewing my writing and providing feedback. I have a team who holds me accountable to my weekly writing goals. Finally, my wife Norma has been an inspiration and source of support through all my work.

I feel like an evangelist when it comes to getting support and including others. In many different areas in my life, I am like a race car driver with a pit crew who is supporting me. They watch my back for me. When I need something, I ask them for help. I don’t see how it is possible to be successful without enrolling others in supporting us and allowing them to participate in our goals and objectives and, ultimately, our success.

One of the reasons many people do not ask others for help is that they don’t want to burden others. This fallacy is easily debunked. Consider for a moment when others have asked for your support. This could be to participate in an informational interview, to come into your office and vent, to get advice, or to provide coaching and feedback. Most people feel flattered when asked and are happy to help. I know I do. Unfortunately, I sometimes forget to apply that to others. So I hesitate to ask when it could really help.

There is another irony in asking for help. When you ask someone to help, they become invested in you and want you to succeed. They are no longer separate from your success because your success or failure reflects their input and help. By extension, they succeed or fail along with you. So, those who invest in you want to see you succeed. Instead of being bothered by your request, they become part of your team and take an interest in your success. And, the opposite is also true. If you exclude people from helping you, you deny them the opportunity to be part of your success.

A good friend of mine was recently responsible for organizing a fund-raising event for a high school coach who had non-Hodgkin lymphoma. He almost hesitated to invite me to the event because it cost $100 per person, and I did not even know the coach. Fortunately, my friend did ask, and I went to the event. I was so affected by the kind words spoken by the friends and family of this coach that I walked away inspired and thinking about my own life. Later, I thanked my friend for including me. I personally benefited because I was impacted by the event. And I was happy to be able to help him. Far from feeling obligated to participate, I felt honored to be a part of this celebration of the coach.

Take a moment and think about your own support team. How would you rate yourself on getting other people involved in your success? Are there areas of your life where you are good at getting support? What are the areas where you tend to fly solo and go it alone? What stops you from involving others in your support?

Techniques for Improving Project Team Leadership

Techniques for Improving Project Team Leadership

1. Techniques to Improve Team Communications

Plan your communications in advance whenever possible. Think through the emotional content, your own feelings, and the emotions of the recipients.

Practice your communications. You can do this alone, with your spouse or children, with a peer or trusted coworker, or with your boss. This is especially important for PMs who get nervous in front of groups.

Speak from the heart by sharing your emotions. Be honest, though, and don’t try to be manipulative or to cover up your emotions; it doesn’t work.

2. Techniques for Conflict Management

Expect conflict and lead by example when it comes to resolving it. Let people know that your style is to be open and take on conflict directly. Refrain from shooting the messenger so that people are willing to bring conflict to you.

One technique that I used successfully involved the opportunity for team members to vent. When I sensed there was pressure on people or that conflict was brewing, I would add a block of time to my weekly team meeting and call it “Open Rant.” Each person would get sixty seconds or so in the meeting to rant about anything they wanted. They did not have to fear reprisal; the team simply held the space for each person to get something off their chest if needed. Not everyone used the time, but the ones that did were able to blow off some steam.

3. Create a Mission, Vision, and Values Statement for Your Project Team

Many people think of a mission, vision, and values statement as something done only at the company’s strategic level. It is also possible to create a mission, vision, and values statement for your project team. Keep it as short and focused as possible. Include your team in the process and the outcome.

4. Cast a Vision for the Team

Whether you use a mission, vision, and values statement or simply talk about your vision for the team, be an evangelist about it. Continue over the life of the project to talk to the team about your vision, why you are excited about it, and how their work fits into that vision. Describe for them the outcomes you see for each team member and the overall team, and encourage them to embrace the goals and objectives for the team.

5. Become a Talent Scout

Getting the best resources is important to the success of the project. The PM should view themselves as a talent maven. They should be constantly on the lookout for new talent to add to the team or to keep in the back of their mind for some future project. When you are impressed by another professional in your field, you should be thinking about how to get them on your team. Add people to your team who are so good they scare you. I’ve actually created a category for my contacts in Outlook that is called “A-Team.” I use that to flag people whom I meet and would like to work with so that I don’t forget them.

6. Become Systematic About Screening and Hiring Resources

PMs who want to lead better will work to develop systematic ways of interviewing and selecting new resources. This is not something that can be left to chance. Develop systems and processes that allow for repeatability and that serve the needs of the project. This might include a checklist for hiring, a skill set template, a two-on-one interview process, or anything else that leads to better selection and hiring.

7. Tools to Address Team Strengths and Weaknesses

Try using the StrengthsFinder assessments for your entire team. The results can be plotted and used as a basis for discussion. This makes for a great offsite team-building exercise early in the life of a project.

In a creative use of the StrengthsFinder, I know of one company that conducted assessments of its top seventy-five managers. During an offsite retreat, the company posted the StrengthsFinder results anonymously and let the management participants use the results to select the leaders for the retreat. The results were interesting and not what they would have been if they had simply used the organization chart to organize the retreat.

8. Expand Your Support Base

Try expanding your support base by getting more people involved in your success. The following list includes many ways to engage people in what you are doing. You will notice that many of these start with “ask.” We need to view an “ask” as an invitation for someone to participate and share in our journey.

1. Enroll your spouse or significant other in your success. Ask them to participate by giving you feedback and emotional support. Or, invite them into the planning of a large goal and then request that they hold you accountable to work toward that goal.

2. Brainstorm about who would be the best person or people to coach or mentor you to reach your particular goals without regard for whether you know them personally or think they would help. Then, reach out to them and ask for their help.

3. Ask someone to be a coach or mentor. If you don’t currently have any mentors, identify someone you respect and ask them if they would be willing to mentor you. If you can afford it, hire a professional coach with expertise in your domain. As an example, I recently hired a personal trainer to help me achieve my goal of qualifying for the Boston Marathon.

4. Ask someone on your current team for feedback on the job you are doing. Be open and receptive.

5. Develop an open relationship with a peer who will serve as a sounding board for your ideas, challenges, and conflicts.

6. Join some type of support team. This could be a weekend running group, a church group, a 12-step program, a professional organization, or whatever else meets your needs.

Personal Action Plan: Project Team Leadership

Personal Action Plan: Project Team Leadership

Project team leadership means communicating with high emotional intelligence and finding the best ways to develop and nurture a team, including selecting and retaining team members.

Key Takeaways

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

My Strengths and Weaknesses in the Area of Project Team Leadership

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. | 2. |

My Actions or Goals Based on What I Learned

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

1 Daniel Goleman. Working with Emotional Intelligence. NY: Random House/Bantam, 1998.

2 Ibid.

3 Harold Kerzner. Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006.

4 David R Caruso and Peter Salovey. The Emotionally Intelligent Manager: How to Develop and Use the Four Key Emotional Skills of Leadership. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004