Creating a Positive Team Environment

In previous chapters, we explored the various aspects of emotional intelligence and project management. We started by looking at emotional intelligence for the PM, then we broadened our view to include interactions with members of the team and other stakeholders.

This chapter looks at how PMs can leverage emotional intelligence to create an environment that is positive and productive for the project team. There is a direct correlation between the team environment and the productivity and satisfaction levels of the team members. Whether intentional or not, the PM sets the overall tone and mood of the project. Through their actions and communications, PMs can create either resonance or dissonance in the project environment. We will look at ways that PMs can carry out their responsibilities and contribute to a positive team environment. Finally, we will finish with a list of techniques that PMs can put to work immediately to improve the environment of their projects.

What Makes a Great Project Team?

What Makes a Great Project Team?

A World of Difference

If you have been involved in enough projects, you will have experienced some project teams that were good, or even great, as well as some that were perhaps not so great. Take a moment and think about a project team that was really terrific. If you are like most people, you can recall a project that was fun to work on; you even willingly worked extra hours. You likely felt happy and excited to be part of the team and sad when the project ended or when you left.

With the memory of that project in mind, think about the things that made that project so enjoyable. What was it about that project team that made you willing to work extra hours or go the extra mile to help others? What was it that made you sad when your time on the project ended? To the point, what were the characteristics of that project that made it so great?

I often ask my students about the projects they felt were great and what characteristics made those projects great. Most students respond that the best projects had the following characteristics:

• Interdependence among team members

• Diversity of team members

• Mutual respect

• The work was challenging

• They shared common goals

• Commitment of everyone

• High performance of all members

• Synergy among members

While not a scientific study, I have found the results consistent across classes. These characteristics are the context of the project. If they are not part of the values of the project or if the values conflict with these, the project environment is going to suffer.

Think about projects you have been on that were not so great. Can you recall a project you did not enjoy and could not wait to leave? Most people have at least one of these on their resume. Let’s hope you were not the PM. What was it like to be in the middle of that not-so-great project? What made you want to leave? How did the project fall short of your hopes and expectations? How would you characterize the environment of that project?

It is amazing how two projects can vary so widely in terms of team morale, productivity, satisfaction levels, and motivation. There is a world of difference between project teams with a positive environment and those without it. Given the two choices, it seems clear that most people would prefer to be part of a project team that has a productive and positive environment.

As PMs, we want to create the best possible team environment to attract and retain great team members and help them to be productive. If we want to get the best from our teams, we need to create an environment that will support our team members and encourage them to perform at their best. The PM is responsible for creating that team environment and setting the stage so that team members can do their best work.

Resonance and Dissonance in Project Leaders

Another factor in establishing a positive environment is the level of emotional resonance or dissonance created by the project leader. In Primal Leadership, Daniel Goleman and his coauthors discuss the concepts of resonance and dissonance as they apply to leadership. Resonant leaders are those who can manage and direct feelings to help a group meet its goals. They leaders form strong bonds with people and create a sense of oneness across a team. Those leaders are in harmony with the team.

Dissonant leaders do the opposite. They create discord and emotional disconnects. Their messages sound off-key because they lack empathy or are unable to understand others. They transmit negative emotional messages that fall flat or, worse, disturb others and create conflict. The caveman manager that discussed in Chapter 4 would be a dissonant leader, as would the difficult and at-risk individuals discussed in Chapter 6.

While there is no 12-step program to cure dissonant leaders, PMs can take the following steps to become more resonant: (1) become more proficient at the emotional intelligent competencies introduced in previous chapters; (2) develop their self-awareness and social awareness to better understand themselves and others; (3) show empathy toward others and place themselves in the shoes of the members of their teams; (4) work to create messages that connect to the emotions and wants and needs of others; (5) show how each team member’s personal goals and objectives relate to the team’s goals and objectives; and (6) emphasize the common purpose of the team and focus on getting people pulling in the same direction.

PMs can evaluate their own leadership style and even learn new styles of leadership. Goleman and his Primal Leadership coauthors discuss four resonant leadership styles and two dissonant leadership styles. We are going to explore these leadership styles in detail in Chapter 9 and will provide some tips and techniques for leveraging these styles.

How PMs Set the Tone and Direction for the Project

How PMs Set the Tone and Direction for the Project

The PM is responsible for the tone and direction of the project. Like the captain of a ship, the PM’s leadership is an invisible force that guides the team.

PMs who are intentional about setting the tone and direction for the project create safety in the project environment. By this I do not mean physical safety, although that is also important. Rather, a safe environment is one where expectations and standards for behavior and performance are clear. PMs create such environments by setting standards, enforcing rules, addressing conflict, holding others accountable, and recognizing others. This safe environment encourages team members to take risks, flourish, and perform at their best.

Have you ever been in an unsafe environment? Unsafe environments are characterized by a lack of team norms, values, and rules. There may appear to be no one in charge, there is an undercurrent of dissatisfaction, and everyone complains about everyone else. Priorities are often not stated and conflict goes unmanaged.

The next sections look at how PMs set the project tone and direction by their handling of the following key PM leadership responsibilities:

• Lead by example.

• Be optimistic.

• Establish team values.

• Enforce the rules.

• Stand up to management.

• Hold others accountable.

• Keep it fun.

• Recognize individuals.

Lead by Example

I was on a large international program several years ago with upward of 100 people on the team. Many were from the United States and Canada, but others were from Europe, India, and the Philippines. My own boss lived in London.

We were moving quickly and scheduled some training in Chicago. Initially, my boss wasn’t going to attend the Chicago meeting because he had been traveling for the past three weeks, and it was taking its toll on him. So, I was a little surprised on the first day of the training class to find that he turned up in person.

This was my boss’s way of leading by personal example. This leader sacrificed to be with the team in the training because it was the right thing to do. Not only was he leading by making the sacrifice, he was also leading by showing that he was not above getting in and getting his hands dirty. He expected the rest of the leadership team to do likewise. Because he had done it, they were more likely to follow his example. And that made me want to do the same.

Does one instance of leading by example create a positive team environment? I don’t know. I do know that a consistent policy of leading by personal example creates predictability and trust, a sense that we are all in it together.

As project leaders, we would do well to lead by example, and to not ask others to do what we are not willing to do ourselves. This might involve staying late or working through a weekend occasionally.

Be Optimistic

One key aspect of setting a positive environment is being optimistic. Optimism in this context means setting positive expectations for how your team will perform and the likely outcomes of your project. Here are some reasons that project leaders should be optimistic:

1. Our optimism is attractive and it attracts followers. As project leaders, we rely on our team to deliver the project. Optimism is a factor in attracting and retaining those high-performing team members we need.

2. Creativity comes from optimism, not pessimism. If you don’t believe this, try to be pessimistic and creative at the same time. Perhaps you will creatively imagine many ways of failing, but you will be unlikely to be creative about positive things.

3. Optimism affects our ability to succeed. More often than not, we get exactly what we expect. So why not expect positive things? Whether we know it or not, what we project is often what we achieve. Conversely, if we are pessimistic, this may easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy. We often make happen what we say we most want to avoid. Or, we want so much to be right that we create failure just so that we can say—“see, I told you so.”

It’s not easy to be optimistic. There are plenty of negative messages bombarding us all day from the media or even within our organizations. As project leaders, we need to manage ourselves to be as optimistic as possible.

Establish Team Values

We talked about team values as part of the mission, vision, and values statement in Chapter 7. As PMs, we need to create team values and ensure that they become more than just words on a page. The team values are the norms of the project team; they are an agreement on how the team will act and treat each other. As PMs, we need to model the team values, communicate them to the project team, and hold the team to those values.

PMs should establish team values early in the life of the project either as part of the mission, vision, and values statement or as identified separately. It is usually best to create the values with the help of the project team, although there may be times when it is better for the PM to set the team values independently.

Once the values are established, we need to make sure that the team lives up to them. We do this by acknowledging team members who demonstrate the values. Several years ago I was one of eight PMs on a large program team. Our core team of PMs, together with the program manager and sponsor, created the team’s value statement during an offsite meeting. Rather than simply writing the values down and forgetting them, the project sponsor had the values printed on memo pads that were freely distributed to all 100 members of the program team. The project sponsor also set up a simple recognition system based on those team values. The recognition system made it easy for any member of the program team to acknowledge and reward any other team member for demonstrating one of the team values. In this way, the program sponsor provided a mechanism for reinforcing the values of the team.

We can also reinforce the values by calling out behavior that is not in line with the values. If a team member is not playing by the rules or is demonstrating bad behavior, we can take them aside and discuss their behavior. We should not tolerate behavior that is contrary to the team values.

Enforce the Rules

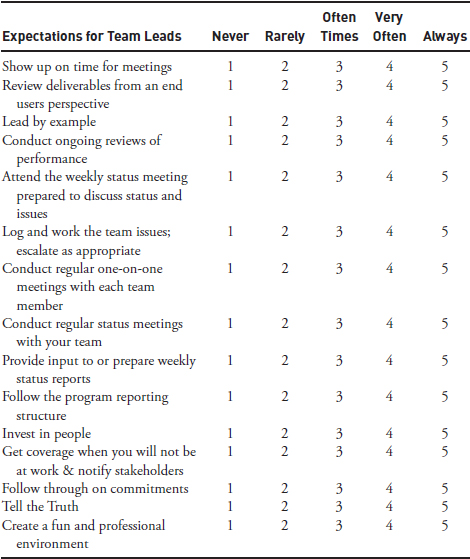

In a similar way, the PM needs to be willing to enforce the team rules. Rules, the way that the PM expects others to behave, can include everything from being on time for meetings to requesting vacation time. An example of an expectations list is shown in Table 8-1. This list identified the expectations I placed on the team leads reporting to me on a particular project. The format provided a means for the team leads to do a self-check that also served as a basis for discussion between me and the team lead.

Once the rules or expectations are made clear, it is up to the PM to enforce those rules. When someone on the team is out of line, the other team members will look to the leader to see if he or she is going to address the issue. Inaction sends a clear message that the rules are not important or that they do not apply to everyone.

For a PM, enforcing the rules may feel like being the heavy, or being a bad guy. PMs may be afraid that they will not be liked or that others will get angry with them. They may want to avoid conflict because that is easier in the short run. This can be a defining moment for a leader.

Table 8-1: Expectations List

Enforcing the rules has a major impact on the environment of the project. Even a seemingly little thing like making sure that people are on time for team meetings can make a difference to the project team. In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell discusses the Broken Windows theory, which links the existence of broken windows in an area to a rise in crime. Essentially it says that crime results from an environment where crime is permitted. The existence of broken windows or graffiti acts as a sort of environmental indicator that crime is tolerated. Individuals who normally would not commit crimes might be tempted to do so if they saw those environmental indicators or if they saw crimes going unpunished. However, if the police crackdown on the broken windows and the graffiti and other petty crimes, the overall crime rates would drop significantly.

In the project environment, the PM is the rough equivalent of the chief of police. The PM needs to enforce the rules. When we enforce the rules, we risk upsetting people, being disliked, or creating conflict. This can be very uncomfortable and scary. We need to push through our fear and address the issue as quickly and directly as possible.

Some project team members will actually get a kick out of breaking the rules. They will test the PM to see if he or she is serious about enforcing the rules. I have seen this manifested in people who fail to ask approval before spending project funds, those who are chronically late to meetings, and those who disappear on vacation without letting anyone know. As noted previously, this could be a sign of passive–aggressive behavior. It could also be a team member testing the limits, like a small child tests its parent’s limits. Like good parents, a PM needs to address the issue as directly as possible, including enforcing consequences.

There must be consequences for those individuals who break the rules. It is preferable to use positive consequences instead of negative ones. PMs may also want to have ready some lighthearted consequences for first-time offenders or for minor offenses. I have heard of teams that build up a small slush fund by requiring anyone who is late to a meeting to contribute one dollar. Some teams have progressive consequences that start out fun and quickly become less fun if the offense is repeated. This could escalate into the offender being removed from the project team at some point. In most cases, however, the best consequence is simply to talk to the offender about changing the behavior.

Here is one final note about enforcing the rules. The best approach is to create an environment where everybody is part of enforcing the rules. In this way, the PM doesn’t always have to be the only enforcer. The team can often exert peer pressure to get compliance. To encourage everyone to play a part, the PM needs to send a clear message about the expected behavior and let it be known that they expect everyone on the team to enforce the rules.

Standing Up to Management

There are times when the PM will need to stand up to management on some issue. Examples include when PMs disagree with a decision or when they need to push back on a proposed change in scope, budget, resources, or timeline. In this context, management means the PM’s boss, major stakeholders, or the client.

The project team members wants to see the PM stand up to management, major stakeholders, or even the client once in a while. They want to know that their leader has the backbone to go to bat for them when needed. They want to feel like the PM has their best interest in mind.

PMs who are unwilling to stand up to management may be viewed as weak or as a pushover. Team members will feel sold out and resent the downstream impacts of PMs who are unwilling to push back. “It all rolls downhill” is a common refrain from frustrated team members. But it is not just team members you need to be concerned with. Managers, major stakeholders, and clients will become wary of PMs who never push back; they will see the PM as weak and ineffective.

That doesn’t mean the PM should fight every decision that goes against the team. PMs need to choose their battles. Bob was one of my PMs who fought every decision and change. He opposed every idea that was not his own. He resisted organizational changes, fought a physical move of his team to bring them into proximity with the rest of the program, challenged budget cuts, and resisted attempts to meet the aggressive delivery schedules our client requested.

Bob was a pain for me to manage. He cooperated only when he was getting his way. Otherwise, he was stubborn, argumentative, and often ineffective.

The problem with Bob was not his unwillingness to fight for his team. It was his inability to know when to fight. He didn’t know how to choose his battles and his approach of always standing up to management did more damage than good. His approach did not serve him or the overall team well. As his manager, I often thought about replacing him with someone who was more cooperative.

We also need to consider the long-term consequences of pushing back. We don’t want to create ill will or enemies. In particular, we should be careful to follow the chain of command when we disagree with a decision or an issue. In most environments, it is acceptable to disagree with your boss. It is usually not a good idea to argue in public with your boss, nor is it good form to go over your boss’s head or around them without trying to resolve the issue with them first. In fact, we should always strive to resolve issues at the lowest possible management level before escalating the discussion. We should exercise extreme caution any time we are about to go over someone’s head, particularly our boss. Going over your manager’s head or skipping levels makes sense only as a last resort. The potential for creating long-lasting conflict is high, and every attempt should be made to work things out first with the manager.

Hold Others Accountable

The effective use of accountability is a powerful lever for the PM. PMs don’t perform the work of the project; they direct and make sure that others do that work. Holding others accountable is crucial when we don’t have direct authority over team resources.

One way that PMs hold others accountable is by gaining agreement on goals and deliverables, stating our expectations for each person, and publicizing team roles and responsibilities. We make the commitments public and then we support others to complete the work as appropriate.

There are three key parts to accountability. The first is to get agreement on the work to be performed. Accountability is not possible without buy-in from the person performing the work. The second is to make that agreement public. PMs publicize commitments through action item lists, status reports, responsibility assignment matrixes, and project schedules. The third is to follow up. As PMs, we need to be proactive to make sure the team members are performing the activities and following through on their commitments.

Some individuals need to be held accountable to perform at their best. When we remind others of their commitments, they will usually work to meet those commitments.

PMs should be prepared for individuals who are unwilling to be held accountable. I once worked with an individual whom we nicknamed “Teflon Don” based on his ability to avoid being accountable. Don was good at avoiding responsibility for tasks. I realized that it was difficult for me to assign work to Don, and it made me uncomfortable to hold him accountable. I wanted to downplay what I needed from him, and when. However, that did not serve me very well since Don rarely delivered anything on that project.

Like Don, some people wriggle out of responsibilities or ignore them completely. PMs who avoid conflict may be scared and find it difficult to bring up the item. It takes courage to pursue individuals and hold them accountable, especially if they are senior to the PM. For example, I used to find it very difficult to hold certain people accountable, including my boss, major stakeholders, clients, and anyone I considered senior to me. Once I recognized this tendency to be scared and play small, I pushed myself to change. I made sure that I recorded the required actions, got agreement on those actions, publicized them, and followed up with the responsible party to remind them of their commitment.

PMs don’t just sit by and watch if others fail in their commitments. PMs support others by reminding them of their commitments, clarifying expectations, and requesting periodic updates. If needed, the PM should also offer support or suggest creative ways to accomplish goals. However, the PM should not take the responsibility back from the owner or let people off the hook.

I once taught a class where the importance of accountability became crystal clear. It was a two-day course. Early in the first day, a number of students requested a thirty-minute lunch instead of the planned sixty-minute lunch. This would allow them to end the day sooner and avoid some of the rush hour traffic. We discussed the proposal as a group, and everyone agreed to the change. What happened next was not surprising. Only about half of the students were back in their seats and ready to start after thirty minutes; the others were missing. Students continued to arrive back from lunch over the next thirty minutes right up until the original commitment time.

It would have been easy to let this go. After all, the students paid for the class, and it was up to them to get the most out of it. However, this course was about emotional intelligence for PMs, who need to appreciate deadlines and the importance of sticking to their commitments. So after everyone returned, we spent some time talking about the incident. We recognized that everyone had agreed to the change, yet some individuals did not live up to their end of the bargain. That behavior penalized the entire class. We also talked about the message that tolerating this type of behavior would send to the team and how other behavior would deteriorate. The message I sent was that people would be held accountable. It was not surprising then that everyone returned from lunch and breaks on time from that point forward.

This unplanned incident turned out to be one of the most talked-about parts of the course and perhaps one of the most important lessons in leadership that those students received from the course. It was a great reminder to me of the importance of holding others accountable.

Keep it Fun

It may seem odd to talk about fun right on the heels of a discussion on holding others accountable, but I think keeping things fun is an important part of creating a positive environment.

Previously, we discussed the importance of appropriate humor as a way to manage our emotions. It is a great way to reduce your stress levels which is a key to emotional self-management. It is also helpful for building relationships with others when you show that you don’t take yourself too seriously and are able to laugh along with others. Therefore, it helps with relationship management as well.

Do you encourage humor on your projects? Have you someone on your project team who is responsible for humor? Do you have someone in charge of making other laugh? Have you made it part of their job description? Perhaps you should think about it. Don’t get me wrong—I need people who are dead serious about their work and the success of the project or program. But, they also need to have fun, laugh at themselves, and not take themselves too seriously.

Let’s face it, the ability to make others laugh is a rare and valuable commodity. I have had several bosses and many team members in my career whom I appreciated because they made me laugh. Someone who can see humor in the situation or create fun when others are getting tense provides sustaining value and a welcome relief.

I had someone on a project team who could not lighten up and have some fun. This particular individual’s fear and anger prevented him from being able to laugh and, in the process, he impacted the entire team. The experience made me realize just how poisonous one individual could be to the entire team. Lack of a sense of humor is not something you can fire someone for, at least as far as I know. Perhaps you can find ways to get that person on board someone else’s team to prevent them from killing the spirit of fun and enjoyment of everyone else on your team.

Recognize Individuals

When my son was seven, he walked into my home office and said, “Dad, you’re pretty smart.” I thought to myself, this kid is a genius and a great judge of character!

It turns out that he was doing an assignment for school. He was supposed to give a compliment and then draw a picture of the recipient’s face immediately afterward. The idea was for him to draw a connection between how people feel when they are recognized. (This is part of the PATHs Curriculum I mentioned earlier).

His assignment was a great idea, and it really got me thinking about the scarcity of compliments and recognition at home and at work. I also think that would be a great assignment for all of us to take on today. Go out and compliment or recognize at least three people, then draw the faces of the recipients immediately after the compliment.

What is so relevant about this seven-year-old’s assignment is that we should all be doing it all the time. As leaders, we all need to do a great job of recognizing the strengths and contributions of others. Recognition is one of the easiest yet most underutilized tools that PMs and leaders have. I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating. No one ever quit a job because of too much recognition! Could you imagine if someone actually gave that as a reason for leaving? It would be unheard of.

In fact, Marcus Buckingham contends that regular recognition is one of the twelve measures of the strength of a workplace. In First Break All the Rules, he uses recognition received in the last week as a key indicator of the health of the workplace.1

In Chapter 6, I referred to recognition as one of the most powerful and underused tools in the PM’s arsenal. In addition to building relationships with others, it is one of the ways that the PM sets the tone of the project environment.

In their book, The One Minute Manager, Kenneth Blanchard and Spencer Johnson introduced the phrase “Help people reach their full potential. Catch them doing something right.”

There is genius in that phrase. One of the things I appreciate most about my mentor is when he says “Anthony, my vision for you is….” It is as if he is holding the bar high for me; he can see me performing at a level even higher than what I believe is possible. It is closely related to the idea of positive regard discussed more in Chapter 10.

That is the model I try to follow for my team members, and I encourage you to do the same. Look for the best in people. Try to see beyond their current performance to their true potential. Hold them to that higher bar and encourage them to reach for that level of performance.

The second part of Blanchard’s phrase is pure brilliance. “Catch them doing something right” encourages us to be on the lookout for ways to recognize people’s goodness. We seek out the best in others and we acknowledge it.

The more natural tendency for me—and many others—is to focus on what people are doing wrong, so that I can criticize or discipline them. It is a habit that I acquired from my critical father. Like any other habit, it can be broken and replaced with better habits. The first step is to recognize that you have a problem. I know that I am most critical when I feel scared or angry. I try to use this awareness to make the shift to being on the lookout for the best in others.

Do you look for the best in others? Or, are you looking for the things that are wrong or need improvement? Whichever approach you are taking, it is part of the tone of the project. It becomes one of the unstated values, and it affects the behaviors of everyone on the team. We send a clear message to the team when we give recognition or when we withhold it. Team members will pay more attention to what is rewarded than to what is said. The recognition informs the team on what is important to the project team leader.

There are many opportunities to catch people doing something right. We can recognize and reward individuals for their contributions to the team, for specific results and outcomes, to reinforce the values and expected behaviors of the team, to build morale, and to motivate people.

Once we catch someone doing something right, we need to recognize that behavior. How do we do it? There are nearly infinite ways to recognize people. I have used public awards, certificates, thank you notes, lunches, and other approaches. One of the best and easiest ways is to simply stop by and thank them. You can also thank them in public, such as a department meeting. Either way, thanking people doesn’t take a long time or cost anything. Tie your thank you as closely as possible to something that the individual did well. It is better not to wait to recognize others.

As PMs, we want to create a healthy and productive environment. We can use the rewards to create an environment of gratitude and recognition.

The Team Within the Team

The Team Within the Team

Up to this point, the discussion about the project team environment has largely ignored the broader organizational environment, that is, the department, division, or company environment that surrounds the project. This could also be a client organization, if that is where the project team is performing.

The reality is that project teams don’t operate in isolation. They are affected by the organizations around them. PMs cannot afford to ignore the broader organizational environment or context, which will impact efforts to create a positive project environment. If the organization environment is positive, the PM will have an easier time creating a positive project environment.

Negative Environments

PMs need to be concerned about the organizations that are not so positive. For example, I once worked for a small company whose CEO was trying to change the culture from a friendly and collegiate environment to one that was professional and client focused. I was inadvertently caught in the crossfire of this organizational culture change, as I led a large project team with a priority on meeting client needs and expectations. In several cases, my style of delivering what the client needed collided with the longstanding culture of scholarly debate. In one memorable incident, the CEO told me to keep doing what I was doing. He said that he would “deal with any ruffled feathers.” I felt happy and supported in my work and that helped to reinforce the client-focused team environment.

What if the larger environment you are working in is not positive? Can you create a positive project environment? Absolutely! I believe this is something the best PMs do naturally. They don’t let a negative organizational environment corrupt a positive project environment. They send the message to their team that the project is different. They communicate the values and rules of the project team, reward those team members who are in alignment, and enforce the rules.

In my classes, I often hear people say “that won’t work at my company,” or “they won’t let me do that.” I don’t know if the statements are true or not. I do believe that the students who make these statements believe them to be true. Either way it is clear that the students don’t feel empowered. In most cases, what is lacking is not permission for PMs to create their own environment, but the courage that PMs need to take risks and be different. PMs have the responsibility to do what is best for the project and the company. This takes courage. PMs often have more power than they think when it comes to choosing their own destiny. There are probably very few rules imposed on PMs, in particular when it comes to setting the mood, tone, and direction for the project.

If you find yourself in a negative environment that stymies any opportunity to create a positive project environment, consider leaving. Why waste your talent on an organization that is not positioned to leverage it? Don’t go home at night thinking that you could be something if only management would let you. Don’t be a victim to a negative workplace.

At a minimum, if you cannot leave the negative organization, at least don’t let yourself be contaminated by the environment. Don’t compromise your own standards for behavior. Be as positive as possible and maybe through a merger, management change, or reorganization, the organization will catch up to you.

Techniques for Creating a Positive Team Environment

Techniques for Creating a Positive Team Environment

1. Assess How Team Members View the Team Environment

I have found it helpful to poll my team to see how they feel about the environment. Most members will be flattered if you ask how they think you are doing in this area. Consider a mini-assessment that will evaluate how you are doing in terms of creating safety, establishing and communicating values, and resolving conflict.

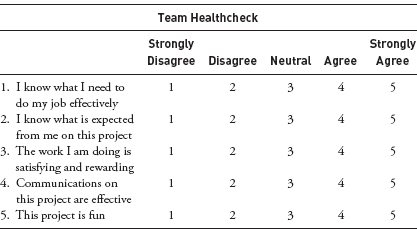

One of my favorite mini-assessments was one I created and used frequently on different project teams to gauge overall team morale. This team health check mini-assessment, shown in Table 8-2, was used to track the health of a large project team on a quarterly basis over the course of a three-year program. I plotted the quarterly scores and used them to see trends and spot potential issues. You can use this tool as it is or tailor it to meet your specific needs.

2. Put It in Writing

PMs may choose to document their expectations for their team members to make sure those expectations are clear. Consider working with the team members to create a set of values, rules, or expectations for team behaviors. Use the example expectations list provided in Table 8-1 as a starting point for your own list of expectations. Here are some additional standards to consider:

Table 8-2: Team Healthcheck Mini-Assessment

Comments: ________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

1. Deadlines for intermediate and final deliverables

2. Quality standards for deliverables

3. Status reporting deadlines

4. Time reporting standards

5. Weekend work

6. Requests for time off

7. Conflict resolution

3. Establish Clear Accountability and Hold People to It

There are a number of tools for making sure that project accountability is clear. My favorite is the responsibility matrix. You can also find sample templates on the Internet or create your own.

When developing a responsibility matrix, list the major deliverables or work assignments in the left-most column. List the responsible people across the top. Use the RACI convention to indicate the role of each person for each deliverable or work assignment, where R = responsible, A = accountable, C = consulted, and I = informed. There should be just one person listed for the responsible and accountable columns.

Once you have established responsibility and accountability for deliverables, you need to hold others to it. Rate yourself on how you are doing in this area. If you are not doing as well as you would like, think about what you need to do to make it better. Are you better with some individual team members and stakeholders than with others? Try to understand what is behind the resistance you feel; it may be your desire to be liked. Determine what steps you need to take to improve in this area.

4. Hold Others to Your Highest Vision for Them

Just as my mentor has done for me, position yourself to hold others to a high vision. Dedicate a chunk of quality quiet time to think about each person on the team and his or her true potential. Try to see people at their very best. Envision what their future could look like and how you see them succeeding.

Then, set up a time to talk about that vision with the individual and encourage them to live up to your vision for them. On an ongoing basis, remind them of how you see them at their best. Continue to adjust your vision to the reality of their growth.

5. Catch People Doing Something Right

Develop the habit of catching people doing something right, and make it part of your leadership style. Make it a point to track your efforts for each individual. Give more to those people who are junior or new to the team to help them integrate.

Establish systems so that you are able to follow through on your good intention of seeing the best in others. One simple way is to use your team roster to create a tally sheet. Track the times you were successful in catching each team member in the act of doing something right.

You might want to create more sophisticated measures for yourself if you are having trouble breaking the habit of catching people doing something wrong. Set a target and track your rate of positive versus negative comments. Reward yourself for achieving your goals when you do. When you don’t, make it a point to up the ante in the next week.

You can also enroll others to support you in this area. Ask your boss, a coach or mentor, or a peer for support and accountability. Or, if you fall short on follow through, ask someone to help you to set a standard or goal for yourself and to hold you accountable to that goal.

You can also spread the wealth by getting everyone involved in identifying positive behavior. Let team members know that you are on the lookout for people doing something right. Encourage them to identify and bring forward examples of people performing well. This will go a long way toward creating an environment of acknowledgement. While you are at it, try to catch stakeholders doing things right also.

6. 1001 Ways to Recognize People

Some time ago I stumbled across a book entitled The 1001 Rewards & Recognition Fieldbook. The title helped me to appreciate that the ways to recognize and reward the individuals on our teams are nearly unlimited.

Do a self-check to see how you are doing in this area. Make a list of the people on your team and track how many times you recognize their work over the course of a week. See how creative you can be in recognizing the work of others. No one ever complained about too much recognition. Let people know that you are serious about recognizing and appreciating the efforts and results of the team.

7. Fix Your Broken Windows

You can apply the broken windows theory to your project environment. Take a moment to conduct an honest assessment to see if there are any rules or standards that people don’t adhere to in your environment. Develop an inventory of the rules and standards, and if there are lapses, develop action plans to address any regulations that are not being followed.

You can get the team or key members of your team involved. Use their input in those areas where you may have blind spots.

Personal Action Plan: Creating a Positive Team Environment

Personal Action Plan: Creating a Positive Team Environment

Creating a positive team environment is necessary for a positive and productive team.

Key Takeaways

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

My Strengths and Weaknesses in the Area of Creating a Positive Team Environment

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. | 2. |

My Actions or Goals Based on What I Learned

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

1 Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman. First Break All the Rules: What the Worlds Greatest Managers Do Differently. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

2 Kenneth Blanchard and Spencer Johnson. The One Minute Manager. New York: HarperCollins, 1981.