Leveraging Emotional Intelligence on Large and Complex Projects

Are You Ready to Lead Large and Complex Projects?

Are You Ready to Lead Large and Complex Projects?

Many PMs see career progression as taking on larger and more complex projects. PMs who want to succeed with these projects must have high emotional intelligence. It is possible to get by on small or even medium-sized projects with low emotional intelligence, but there is very little room for error on a large and complex project. There are too many stakeholders and too many opportunities for breakdowns.

I personally prefer large projects to smaller ones. Larger projects have a higher risk than small projects, but they also have a much greater reward. Often the increase in risk is less than the increase in reward. This is because large projects usually get a high priority within the organization, which makes it easier to attract good resources. Small projects are often given a low priority and are frequently understaffed, which can make them even more risky than bigger projects. For a small increase in risk, larger projects provide more visibility, recognition, and personal satisfaction. I generally recommend that people step up, take on the risk, and go for the large and complex projects.

If the thought of managing a large project intimidates you, this chapter should be of interest. We look at the characteristics of large and complex projects and how emotional intelligence plays a role in our success with those projects. In addition, Daniel Goleman’s six different leadership styles of inspirational leadership are presented, along with a discussion of how good leaders need to select the style appropriate to the situation, the characteristics of each of the inspirational leadership styles, when to use each, and the emotional intelligence competencies that underpin those leadership styles. The chapter also explores the world of virtual teams and ways to bring emotional intelligence into those virtual teams. We close with a set of techniques intended to help you succeed when you manage large and complex projects.

Characteristics of Large and Complex Projects

Characteristics of Large and Complex Projects

While all projects are different, large and complex projects tend to have similar characteristics that differentiate them from small projects.

Stakeholder Conflict

All projects come with conflict. On large projects, various stakeholders will often disagree about the goals and objectives of the project. Some groups will receive benefits, and others will experience greater costs or penalties. This leads to built-in conflict that may be in the open or that may be underground.

Layers of Staff

Large projects tend to have large project teams. The larger the team, the less direct contact the PM has with each team member. The largest projects will have subteams headed up by team leaders or PMs. This affects the PM’s communication plan and approach as well as choice of leadership style.

Vendors and Subcontractors

Large projects are more likely to include vendors or subcontractors than small projects. When dealing with vendors and subcontractors, the PM needs the ability to negotiate with, direct, and lead those third parties in order to achieve the goals of the project.

Importance to the Organization

Large projects are usually more important to the organization than smaller ones. There is a larger investment in resources, greater expectation for returns, and a higher priority placed on success. While it is usually desirable to lead those critical projects, the priority, importance, and visibility can place pressure on the PM and key stakeholders to succeed. A lack of strong self-management skills can lead to emotional breakdowns that disrupt the team and undermine the PM’s effectiveness.

Role of the Project Manager

With a large team, the PM role is less likely to be related to the deliverables and more likely related to leadership, stakeholder management, facilitating, coaching and mentoring, and delegation.

Virtual Teams

With the increase in team size comes an increased likelihood that there will be a virtual component of the team, that is, some of the team will be working remotely. PMs have to deal with time zone and cultural differences, and this work is frequently done over the phone. We will look specifically at tools and techniques for applying emotional intelligence to virtual teams later in this chapter.

Concerns for Large-Scale Project Managers

Concerns for Large-Scale Project Managers

As PMs take on large and complex projects, the types of issues that they deal with will change, as these projects have some unique concerns.

It’s Lonely at the Top

The bigger the team that the PM is managing, the more likely it is for the PM to feel isolated and alone. With a small team of three or four members, the PM can feel like part of the group. However, the likelihood of feeling isolated increases when a PM is managing seventy or more members, particularly if the PM has many direct reports. Team members are less likely to engage you in conversation, invite you to lunch, or include you in activities outside work. PMs can begin to feel sad, lonely, and isolated.

PMs can overcome this loneliness by investing in the relationships with team members and by reaching out to others for support. Team members who are uncomfortable initiating conversation with the “boss” may welcome invitations from the PM for conversation or for lunch. In addition, the PM should be using regular one-on-one meetings to develop and invest in the relationship with each individual.

The PM should also develop a support network of relationships to lean on when needed. The network could include the relationships with their own manager, peers, and mentors. It may also include relationships outside the work environment, such as family, spouses or significant others, support groups, fellow members of professional organizations (like PMI), and coaches.

Role of the Project Manager—Delegation

Managing large and complex projects requires us to step away from the day-to-day details, activities, and deliverables. PMs need to be focused on leadership, stakeholder management, facilitating, coaching, and mentoring. Stepping away from the day-to-day aspects of the project does not mean abandoning them. It does mean delegating the responsibility for those deliverables and activities and holding others accountable for the results.

Delegation can be challenging for PMs, especially for those with subject matter expertise or those accustomed to being involved in the details. The reason that delegation is challenging is usually rooted in fear and a lack of trust:

• PMs do not trust their subordinates to do it right (or to do it their way).

• PMs do not trust their subordinates to get it done on time.

• PMs are scared that if the subordinate does the work, the PM may not be viewed as valuable.

• PMs are scared to not to be in control over the activity and how it will reflect on them.

Delegation is a critical skill for PMs who want to grow and take on larger projects. If you are not good at delegating, try the following to improve your delegation skills:

• Use the self-awareness techniques to understand the emotions that come up for you around delegating. Are you scared, and if so, what are you afraid of?

• Be aware and mindful of your desire to control. Practice letting go of how the work gets done and focus only on the results.

• Practice delegating as a learning experience for you and for the delegatee. Start small and work your way up, developing yourself and your resources as you go. Talk about the experience with them before, during, and after.

• Develop a responsibility matrix and use it to identify responsibilities and hold others accountable.

Importance of Business Skills Versus People Skills

The application of emotional intelligence has focused on improving our interpersonal skills. This does not mean that technical and business skills are not important. In fact, to be effective and manage large and complex projects, PMs must have people skills, business skills, and some level of technical skills. The exact mix of required skills is going to vary based on the industry, project type, and organization. Those PMs with a strong set of interpersonal skills who also understand and can speak the language of the business will succeed over those without the business skills.

The reality is that running a large project is a lot like running a small business. In large-scale projects, we need to pay attention to both business matters and people matters. We need to balance the other core project management skills like contract or integration management with EI skills like empathy and self-awareness. We need to apply the correct leadership style to the project.

Applying Different Leadership Styles

Applying Different Leadership Styles

In the large project environment more than any other place, the PM has to be flexible in approach and have the ability to vary leadership style. In Primal Leadership, Goleman and his coauthors described six inspirational leadership styles. Four of those styles are considered to be resonant, that is, they cause a positive effect on the team environment.

• Visionary

• Coaching

• Affiliative

• Democratic

The remaining two leadership styles are considered to be dissonant. The dissonant leadership styles are those that cause disturbance or disruption in the team environment.

• Pacesetting

• Commanding1

Let’s look at each of these styles in detail to see how PMs can apply them and to understand the underlying emotional intelligence competencies. We will also look at some of the considerations that go into deciding which leadership style is appropriate for a given project. As you read about each of the leadership styles, think about your own project history. See if you can determine your own dominant leadership style.

Visionary Leadership

Visionary leaders tell people where they are going; they provide the vision and the big picture. On a project, visionaries describe the end goals, but leave individuals plenty of latitude on how to achieve them.

The attraction of the visionary leader is the ability to connect the individual’s work with the vision for the project so that team members understand how their work fits into the big picture. Team members benefit from a leader who shows them not only how what they do connects with the vision, but also why what they do is important. Visionary leaders help the team members to resonate with the project goals and objectives.

The visionary leader relies heavily on the emotional intelligence competencies of self-awareness, self-confidence, and empathy. In particular, empathy is critical, as the visionary needs to understand where people are in order to help them connect to the bigger picture. Vision casting is also an important emotional intelligence competency for visionary leadership.

Goleman’s research indicates that visionary leadership is the most effective style of leadership. However, there is a caveat to the use of the visionary style. That is when there are many experts or more senior people reporting to the PM. In those cases, the vision casting by the PM may fall flat and fail to resonate with those experts or senior people. The visionary may fail to get the appropriate buy-in. Otherwise, the visionary leadership style would be appropriate to any type of project. It would be especially beneficial to projects that are in recovery mode or those that are stalled and need a fresh vision to energize the project team.

Coaching Style

The coaching style focuses on personal development rather than on the accomplishment of tasks. A PM with a coaching style sees the project as the vehicle for the development of the members of the team. The goal of accomplishing the project is almost secondary to the goal of helping people to learn and grow. The project becomes the vehicle that we can use to help people stretch and develop. The key outcome for the coaching style leaders is the growth of the team members.

I had an excellent manager named Rick for several years; he was a terrific example of the coaching style leader. We worked together on three large projects over the course of about four years. Rick showed great interest in my development, and he encouraged me to share with him my long-term goals. In return, he showed me how my current assignment would benefit me and how it connected to my long-term goals and objectives.

One hallmark of Rick’s style was his use of one-page weekly objectives. He worked with me to break down my responsibilities into weekly goals that fit on one page. We sat down together each week to develop the objectives. We started by reviewing the goals from the previous week, discussing in detail the progress that was made and any hurdles or issues. Then we would jointly set the objectives for the next week. Though the document would have appeared cryptic to an outsider because of our shorthand notes, we both understood precisely what it meant. Our initials at the top of the page indicated that both of us were committed to the goals.

The one-page objectives worked for that relationship, but they are not necessary to use the coaching style. It is critical, though, that the PM be involved with the team members at a detail level. The PM coaches the team member with specific steps and provides encouragement and feedback as they perform.

Another key to the coaching style is the manager’s belief in the ability of the team member. I always felt that Rick firmly believed that I could do anything. He didn’t seem to think that I had any limitations and his one-page weekly objectives often included stretch goals that I would not even have attempted had he not encouraged me to believe they were possible.

Rick’s belief in me encouraged me to try to accomplish the goals even when I didn’t see a way to make them happen. Once I ran into some trouble meeting key project milestones. I wanted to take the easy route of pushing out the schedule. This would delay the entire project, cost my company money, and disappoint the client. Rick told me flat out to go back to the drawing board and come up with a solution that did not involve delaying the project. His confidence that I could do it encouraged me to look for that creative solution. I chose to believe that there must be a creative solution if Rick thought that there was one. As it turned out, I was able to come up with a solution that enabled us to hold the line on the dates.

It is easy for me to understand why the coaching style leads to high motivation levels for the team members. I felt motivated to meet the high expectations Rick had for me. I wanted to do what he asked me to do. In fact, I continually raised my own internal standards and expectations based on his expectations for me. If he thought I could do it, then I chose to believe that I could.

The coaching style works best when employees seek direction and feedback and are willing to partner very closely to get agreement on the work to be performed. It requires a high level of trust between the coach and the team member.

The coaching style doesn’t work when trust is lacking, when team members are not interested in getting input on their performance, or when the team member feels micromanaged. On a recent project, I consciously applied the coaching style to four different junior members of the same team. With two of the members, I was very successful. Those two team members saw my involvement with them as an investment and kept requesting feedback on a regular basis. The coaching style failed with the other two team members who saw the same style as de-motivating, critical, and micromanaging. These team members did not like my close involvement and found the coaching demeaning. They wanted to have the latitude to work without checking in with the boss. The main differences in these relationships were the emotional intelligence level of the team members and the level of trust. In those cases where the team members were secure about their role and believed that I had their best interest in mind, it worked great. When the team members had low emotional intelligence or did not trust that I had their best interest in mind, the coaching styles failed.

Affiliative Style

Affiliative leaders are great relationship builders. They tend to focus less on tasks and goals and more on building relationships with their team members. Affiliative leaders create an environment of harmony and friendly interactions. They work to nurture personal relationships using empathy and conflict management.

With affiliative leaders, feelings and relationships are a clear priority. Taken to an extreme, feelings are given priority over results. Affiliative leaders may find themselves wanting to be liked, and they may make decisions that place a priority on being liked. Team members may view affiliative managers as soft or indecisive. Team members may also feel they are in the dark about the project direction and their work. They may feel left on their own to make decisions.

I once worked for an organization that emphasized the affiliative style. The company had grown quickly from a partnership between the two founders to being part of a large corporation at the time that I joined. Yet the cooperative nature of the original partnership was part of the DNA of the company and a priority was placed on everyone getting along.

My manager Tom ran the project management office, which included all the PMs. I was helping Tom with the development of the standards for project delivery, including methodology and best practices, but I was continually frustrated by his insistence on getting input from all areas of the company and involving others in the discussion. In our efforts to get cooperation from across the company, it was not possible to get consensus without watering down the methodology to the point where it was unusable.

Tom was ineffective because of the priority he placed on everyone getting along and on being liked. He was very good at relationships; unfortunately, he was not able to get the results he needed from the project management office.

The affiliative style of leadership works best when you are trying to improve morale and communications or repair broken trust. The affiliative style will not work as well when leaders fail to do the right thing in order to be liked.

Democratic Style

The democratic style is similar in some ways to the affiliative style. Democratic leaders tend to take input from many sources. This input leverages the experience of the team, provides for better decisions, and gets buy-in from the entire team.

Early in my career I worked for a democratic manager named Charley, who was responsible for a corporate-wide competency center. In his role, he supported engineers and engineering managers across the company. In turn, funding for the competency center was provided by each of those engineering managers.

What worked well for Charley was his willingness to get input from everyone. He was a good listener and would spend time with the engineers he supported to find out what they needed. As a former engineer himself, Charley was empathetic to their situation and could place himself in their shoes.

The downside to the time Charley spent working one-on-one with the engineers was the lack of overall direction for our group. Those of us who worked for Charley felt like we didn’t know where the group was heading. We seemed to spend more time talking about our work than actually completing work. For example, we were always preparing presentations on the projects we were working on at the competency center and their value to the engineers. We were busy trying to sell the value of the competency center rather than completing the work required.

A big disadvantage of the democratic style, as demonstrated by Charley, is a perceived lack of decision making. Democratic leaders may seem like all talk and no action. They are often struck by delays and conflict. Further, there are times when consensus doesn’t make sense and it is more important for the leaders be decisive.

Pacesetting Style

The first of the two dissonant leadership styles is the pacesetting style. Pacesetters are usually individuals with a high personal drive to achieve. The pacesetting leader expects excellence and models that to the team. They have high expectations for performance and for continuous improvement. Pacesetting leaders tend to put pressure on everyone on the team to perform at their very best.

The pacesetting leader places a high priority on results, and this can hurt their relationships with team members. Pacesetters often lack empathy; they tend to believe that everyone thinks like they do. Like perfectionists, pacesetters often feel dissatisfied with the current performance and want to continue to improve it. The pacesetters’ message that they are dissatisfied with the current performance can lead to alienation of team members who feel blamed and criticized. Team members may feel that they cannot do enough to measure up.

I have seen the pacesetting style used by Mike, a friend of mine who is a leader in a private business. Mike is obsessed with competition and improvement. Whether he is at work or at play on the golf course, he is competing and pushing everyone around him to do better.

Mike and I share an interest in running. His pacesetting style comes through in his training, when he pushes himself hard to run as fast as he can. Not only that, he encourages everyone around him to push themselves. Once when we had planned to run ten sprints of 800 meters each, I mentioned that I wasn’t going to run all ten. Without flinching he said that anyone who didn’t run all ten sprints was a wimp. That comment made my competitive juices flow. His comment made me want to push myself, which was exactly what he intended.

A well-known pacesetter is Michael Jordan. Jordan’s style of play and leadership on the basketball court sent the message “keep up with me if you can.” Jordan was always pushing himself and his teammates. He played hard and expected those around him to play hard as well.

A couple of Michael Jordan quotations reflect his pacesetting style and his obsession with winning. Jordan once said that “There is no I in team, but there is in win.” He also said “I play to win, whether during practice or a real game. And I will not let anything get in the way of me and my competitive enthusiasm to win.”

The danger of the pacesetting style is that the team can begin to feel as if nothing is good enough. Pacesetting managers never seem to be satisfied with the current performance. They overlook the positive and tend to focus in on what is not yet working or what can still be improved.

I have unknowingly applied the pacesetting style in previous projects. While it is not my dominant style, I have found it easy to focus on continuous improvement and lose sight of the needs and feelings of my team members. I didn’t take the time to acknowledge what was working and recognize people for that.

There are times when the pacesetting style is appropriate. It works best when you are leading a team of experienced and competent professionals. It also works well when paired with the visionary or affiliative styles. It doesn’t work well when used exclusively or when you are dealing with inexperienced team members who need more positive encouragement and feedback. It doesn’t work with team members who don’t perform well under the pressure exhibited by the pacesetting leader. In any case, the pacesetting style should be used sparingly.

Commanding Style

The commanding style is one in which leaders require everyone to do it their way. PMs who use the commanding style don’t want questions; they want compliance. They are reluctant to share power and authority, and they rarely take the time to explain themselves fully. Like the parents of a small child, commanding leaders may come across as saying, “Just do it because I said so.”

I had a manager named Bob who used the commanding style. He was recruited to take over and turn around a large program that had failed. The program included three major projects and several hundred team members. I was part of Bob’s recovery team.

Bob quickly made it clear to everyone that he was in charge and that things were to be done his way. He also made it clear that the failed policies and practices of his predecessor would not be tolerated. He was ruthless about enforcing his way and showed no compunction about removing individuals from the team even for minor issues. He would joke about firing individuals from the team and kept a running tally of the number of “drive-by firings” he had performed.

Bob was highly successful in the program recovery and earned himself an award from the chairman of the company. In this situation, the commanding style worked because it was appropriate. Bob’s military background contributed to his command and control approach, which is characteristic of the commanding style. Bob needed to be clear about his expectations for people and he demanded that people change from the ways of the previous program manager. Unfortunately for Bob, it was the only style he knew and he used it in every situation.

Bob was a lot like my dad so initially I found it easy to work for him. His style was both familiar and predictable to me. Bob was extremely critical and often seemed to be personally attacking me or other team members. Eventually, however, his style of leadership took a toll on me. Like other leaders relying on the commanding style, Bob lacked the people and relationship elements of the affiliative or democratic styles or the attraction of understanding the big picture that is characteristic of the visionary style.

The commanding style should be used sparingly. It works best during emergencies or crisis situations, such as during a project turnaround, when there is no time to explain the rationale behind every decision. Otherwise, the commanding style takes a toll on the team and should be avoided.

Application of the Leadership Styles

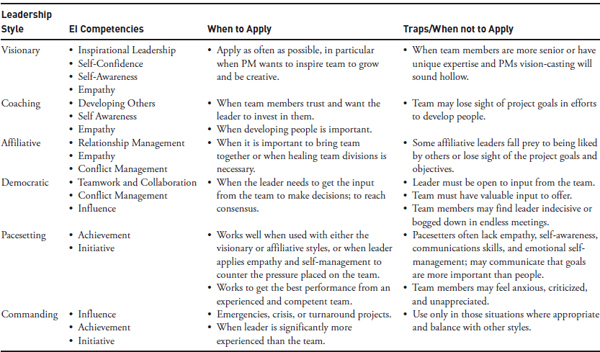

Table 9-1 shows each of the styles, the underlying emotional intelligence competencies required for the style, project situations to apply that style, and any traps or situations not to apply the style. Most leaders have one dominant style of leadership. Based on the descriptions above, were you able to identify your dominant style?

Good leaders are able to use different leadership styles in different situations. To excel on large and complex projects, we need to be able to switch and adjust our leadership style to the needs of the situation. Daniel Goleman likens the various leadership styles to the golf clubs a player has in their bag. Each club has a different application. The more clubs that players have, the more flexibility they can bring and the greater their chance of success.2

Consider what steps you need to do to expand the styles available to you. In particular, if you rely predominantly on the dissonant leadership styles, a quick win for you will be to incorporate one or more of the resonant styles.

Applying Emotional Intelligence to Virtual Project Teams

Applying Emotional Intelligence to Virtual Project Teams

The Challenges of Virtual Teams

Increasingly, we are working in teams that have at least some virtual component. On large-scale projects, virtual teams are almost a given. Virtual teams are composed of people who are working in different physical locations rather than side by side or face to face. It is not uncommon to have executives in one location, end users in another, and development teams in a third. Often, the team members are in different time zones, which adds further complexity. There are often cultural differences to be considered.

Table 9-1: Leadership Styles

Emotional intelligence is more important than ever for virtual teams due to the reliance on the telephone and email for communications. Neither medium allows for seeing the face or body language of the team members and that makes communications and relationships more difficult.

I have been part of the leadership team for two very large programs with considerable virtual components. In the first case, we were implementing an enterprise-wide solution across a multinational corporation using an international team of over 120 people. In another program, we were developing and implementing solutions for a country in the Middle East. We used over 100 resources in locations from the Middle East to the West Coast of the United States. Keeping everyone on the same page with a virtual team can be a struggle for PMs. Many of the following tips and techniques were learned from these program experiences.

Emotional Intelligence Helps Virtual Teams

Applying EI techniques in the virtual environment may be more important than anywhere else. Here are some ideas for making virtual teams work for you.

Face-to-Face Meetings

To get the most out of virtual meetings, make it a point to have at least one face-to-face meeting with each team member early in the project. This will help the communications later when you cannot see the team members’ faces or read their body language. If possible, I also recommend that you make it a point to meet in person over the course of the project.

When I had a virtual team working for me on the other side of the globe, I initially did not think it was necessary to travel there just to meet with them. However, I did travel there on several occasions. I learned that even if I was visiting for other reasons, I could still make time to meet with people one on one and in groups in order to connect. In fact, I made it a point to go out to lunch to get to know them personally and understand their goals and objectives. The meetings I had served me over the life of the program.

Another application of the face-to-face meeting is when part of the team is local and part is working virtual. When some team members are dialing in, the local team members may gravitate toward calling in from their desks or homes instead of coming to a central meeting location. I have been on calls where individuals in side-to-side cubicles both dialed in to the same teleconference. Their logic is that since everyone cannot be together, there is no reason for the local team to get together. This approach tends to be isolating, and it works against the PM. Team members are more likely to be multitasking than engaging with one another at these types of teleconferences. A better approach is to stress the importance of face-to-face meetings and request that individuals make it a priority to meet as a group. This may not always be possible, but it will be more likely if the PM requests it.

Leverage Technology

Use technology to improve your communications with remote team members. The ways to do this are limited only by your creativity. Technology enablers include the use of instant messaging (IM), satellite or cell phones, text messaging, bulletin and discussion boards, blogs, a project web site, voicemail distribution lists, video conferencing, teleconferencing, email, Skype, Face-Time, and collaboration tools.

The key is to make the technology work for you and the team, not against you. For example, some PMs are not familiar with IM and may view it as a tool for goofing off. Rather than fight it or outlaw it at your company, as a leader I know recently did, embrace it. Get on board with it yourself and use it to connect to the more technically savvy members of your team.

One time, we used a map as a low-tech way of staying connected. A key team member left his home in the United States and traveled between London and Shanghai. He was still a project leader and still dialed in to the project teleconferences. We used a world map and a small icon of him and his family to track where he was. In this way, we were able to better connect with him. He was more than simply a disconnected voice on the phone.

In the same way, consider including pictures of all team members available in a central location or on the project web site. Traditional teams can take a page out of the Agile team playbook. During intense periods of activity, they can use a daily coordination meeting called the standup or scrum meting to align activities across all locations.

Make Communications Work for Everyone

Good communications planning and stakeholder relationship management should help to identify and resolve communication needs. However, recognize that on virtual teams, it is easier than ever to get disconnected. PMs should constantly evaluate the regular communications and make sure that they are sufficient and that all stakeholders’ needs are being met. On every project there is invariably an occasion where some stakeholder steps forward and says, “I didn’t know that” or “I never heard about that.”

Don’t be afraid to experiment with your communications. During intense periods of activity, it may be necessary to coordinate across all the work sites with a brief “stand-up” type meeting once per day. Or, it may be appropriate for each team to hand off its work at the end of their day when you have teams spread across time zones.

As the PM, be aware of the amount of time you spend with each stakeholder and those reporting to you. With a virtual team, it is very easy to spend more time and better quality time with those who are located near you than those who are remote. You can compensate for this by investing more in those who are remote. If you spend thirty minutes every week with each direct report in a face-to-face meeting, consider spending forty-five or sixty minutes on the phone with those who are remote.

Try to be consistent across locations. If you have an all-hands meeting in one location, either have others dial in or repeat the meeting with those who are remote. Develop and share frequently asked questions with the entire team. Archive and distribute minutes from those meetings for any individuals who are not able to attend.

Use Humor

When it works, humor helps us to connect and see each other in a more positive light. It can bring levity to situations and lighten tensions so people feel more comfortable. If your virtual team spans countries and cultures, use of humor can be even more risky.

Humor can also work against us, particularly in the virtual environment where facial expressions and body language are not available to indicate that someone is “just kidding.” In virtual environments, it may not be possible to hear others laughing or to get the responses of others to our own humor. Humor, when it doesn’t work, can highlight the differences between people and serve to alienate us.

As a general rule, humor works best when team members know each other. When individuals do not know each other, humor can be easily misinterpreted or misconstrued. Self-deprecating humor works better than poking fun at others. In general, PMs should avoid joking about others, especially if they are not present. Joking about others can cause distrust and alienation among the team.

As a PM, I create an environment in which people know that I try not to take myself too seriously. I joke about myself and point out the things that I do that people find funny. At one point another PM pointed out that my jokes were not very funny and offered to raise his hand in meetings so that others would know I was joking.

Injecting humor into our written status reports can breathe some energy into what are often very lifeless documents. Use of humor can make the document more interesting and easier to read and may lead to more status reports actually being read.

I once had a PM who wielded humor very effectively as part of a large virtual team. His daily status report from the client location in the Middle East included a mini trivia quiz at the top. Every day he added a movie quote to his status report. Between his use of humor and the movie quotes, he created a report that was well read by the rest of the team.

Build Relationships Off the Call

Virtual teams are often characterized by a seemingly endless series of teleconferences, which tend to be formal and typically lack opportunities for developing interpersonal relationships. Individuals can be lost in the formality and structure of all of these teleconferences. Relationships with team members may be superficial, and the team members may view the PM as lacking in warmth and personality.

To improve relationships and make teleconferences more personal, use the time off the call to invest in and build relationships with virtual team members. Don’t limit your investment in them to the structure of a regular meeting. Use the time off the call to let your true nature show. Be as informal as possible and encourage them to talk and to share their concerns, interests, hobbies, and objectives. PMs can leverage Skype or other low cost video conferencing tools to build these relationships off the call.

Emotional Intelligence Techniques for Large and Complex Projects

Emotional Intelligence Techniques for Large and Complex Projects

1. Learn to Identify Leadership Styles

You can use your experience to help you identify different leadership styles. Make a list of the PMs and other managers you have worked with over the last five or, even, ten years. For each one, identify the emotional intelligence competencies you experienced with them. See if you can identify their dominant leadership styles. Evaluate, if possible, whether they used different styles with different team members.

2. Identify Your Dominant Leadership Style

In this exercise, you will determine your own dominant leadership style. Start with the list of EI competencies. Based on what you know about those from the earlier chapters, list the ones that you feel are your strengths. Then reread the descriptions of the six leadership styles. Is one of them clearly your dominant style? Or, do you believe that you use multiple styles?

Take this exercise one step further by getting input from others. Ask those on your current team to review the list of characteristics of each of the leadership styles and see if they can determine your dominant style. You can expand the discussion to your boss, spouse or significant other, and perhaps even your own children as appropriate. Get as much input as possible to see yourself as others see you.

3. Build New Leadership Muscles

Once you determine your own dominant leadership style, select another style that would best complement it. If you don’t currently use visionary leadership, that would be a great choice since research has shown it to be the most effective.

After selecting the leadership style, start with the underlying emotional intelligence competencies for that style. Once you determine which competency you need to strengthen, go back to that competency in the previous chapters. Review the various techniques provided for improving that competency.

If you need help, consider enrolling someone in this process. A mentor or even a member of your team would be in a good position to help track your progress and provide feedback as you build those new leadership skills.

4. Improve Your Delegation Skills

If you find delegation difficult due to fear or control issues or if you just want to improve, there is no time like the present. Decide today to begin to practice delegating. Start small and perhaps with the person you trust the most. Gradually increase your level of delegation while you monitor your feelings and emotions around the process. Track your progress and celebrate your successes in this area.

Alternatively, identify someone in your work environment who is good at delegating and ask them to help you to improve. Find out what works and doesn’t work for them and try those techniques for yourself. Set goals and ask them to hold you accountable for the results.

5. Check the Roster for Your Virtual Team

If you are managing a virtual team, take the time to walk down through the roster of team members. Are you connecting with everyone on the team, especially those you don’t see? Make a note of how much time you spent in the last few weeks with each of the team members. Is that amount appropriate for the size of the team and the role of the individual? Are there any team members who are not getting enough of your time and attention?

Consider polling your virtual team members to find out how well connected they feel to you. Put together a short survey or simply call each of them. Either approach will provide valuable feedback. Calling them may reveal information that a written survey will not. However, team members may be more forthcoming with a survey than they would with a phone call.

6. Work on Relationships “Off the Call”

If you are leading a virtual team, what steps are you taking to build relationships? If the communications are typically conducted through a series of conference calls, select a member of the team you don’t know well and choose to work on that relationship. Make it a point to call them or visit them off the call and get to know them on a personal basis.

Personal Action Plan: Leveraging Emotional Intelligence on Large and Complex Projects

Personal Action Plan: Leveraging Emotional Intelligence on Large and Complex Projects

PMs who want to succeed with larger and more complex projects must have high emotional intelligence.

Key Takeaways

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

My Strengths and Weaknesses in the Area of Leveraging Emotional Intelligence on Large and Complex Projects

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. | 2. |

My Actions or Goals Based on What I Learned

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

1 Daniel Goleman, Richard Boyatzis, and Annie McKee. Primal Leadership. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002, p. 55.

2 Ibid., p. 54.