Chapter 6. Forecasting the Future with Feelings

IMAGINE IT’S 10 YEARS ago, and I tell you about an idea for taking photos that disappear after they’re viewed. Maybe I add a detail, like there would be virtual “stickers” that you could put on the pictures or that you could write on them before they disappeared. Meh. Polaroids had their day already, hadn’t they?

How many of us would have predicted that Snap would have such emotional force? And that Polaroid would make a comeback, too? If there’s one truth about happiness, it’s this: human beings are terrible at predicting it. We overestimate how happy we will be on the weekend and we underestimate how happy we will be on Mondays. We think that we’ll be happy when we have more money, even though that is consistently not the case. We make these same mistaken predictions over and over again.

Emotional intelligence is a bit of a time hack. When you’re overcome with regret, you’re paying too much attention to the past. When you are feeling distracted, you’re not appreciating the present. When you worry, you’re dwelling on an unpleasant future. Negative emotions not only signal some bigger-picture frustrations; they can also spiral into despair in which the future feels hopeless. By shifting attention to the past, present, and future in a positive way, you can effect real change.

In this chapter, we mix techniques from affective forecasting, prospective psychology, future foresight, and speculative design. Paying attention to emotion can guide us toward a fulfilling future. So, let’s try a little emotional time travel to help us to make better design decisions for our future selves, and our future society.

The Trouble with the Future

One definition of design, and one that is especially true of designing technology, is that design creates the future. Quite literally, we develop objects to exist in our future lives. At a high level, we see our role as designing a better future. But, day to day, we focus on a very near future in quite a particular way.

Design thinking (or its close relations like human-centered design, user experience design, and human–computer interaction; let’s not quibble) has made our lives easier and more comfortable. It has enabled organizations to provide products and services that function with less friction. It encourages customer empathy. Design thinking has developed solutions from mobile payments to self-driving cars. We use problem solving for good, too such as 3D-printed prosthetics and LED lights for the developing world. Design thinking has become a shorthand for a mindset and a method that creatively solves problems.

Lately, we’ve been running up against its limitations, though. Although it offers a repeatable creative process for designing commercial products that benefit an individual in the moment, it’s not the only way or the best way to build an emotionally sustainable relationship or to encourage positive transformation in the long term. Let’s consider just how we get stuck.

THE PROBLEM PROBLEM

Listen closely and you’ll notice that conversations about design often come back to problems and solutions. Whether we are talking about autonomous cars or fake news or world hunger, we tend to see the world as a series of discrete problems to be solved. We zero in on an unpleasant state and then fix it in the short term.

Design thinking offers a method to address tightly focused problems like a thorny moment in the checkout process. It also applies to big-picture issues, like shaping a platform to educate homeowners about the risks of flooding. Even the way we structure design thinking in the organization—as a sprint—rushes us toward the short term. We get rid of the problem for now, and then on to the next problem.

Except that sometimes we create that next problem. Solving an individual problem can sometimes cause another problem for that individual. You might feel bored and a little lonely one afternoon, so you start watching a streaming video service of your choice. It’s entertaining, it fills up that empty feeling, and it’s so easy to keep going. The more you binge-watch, the more isolated you might feel. Rather than solving your boredom and loneliness, you’re caught in a cycle.

Perhaps our problem-solving creates a larger societal problem. Smartphones increase access to information, which seems to quantifiably increase well-being, but they add a tremendous amount of waste to the environment. Ride-sharing services make it easier for individuals to get rides, but make it more difficult for taxi drivers to earn a living wage.

Beyond that, the mundane everyday problems that we are solving might inadvertently erase foundational elements to emotional well-being, like personal growth and community building. Getting groceries is such a bother, so instead we create a digitally enabled convenient option. All good, until we look at all the other things that might be missing. Flipping through cookbooks together, conversations about what to purchase, inventing new meals because we don’t have everything we need, and casual conversations with neighbors at the store are just some of the little things lost from solving the grocery problem.

Another problem-solving tactic we fall back on is giving already acceptable experience an upgrade. You have a photographer, but wouldn’t an aerial drone view be cooler? You use the surface of your refrigerator to display a drawing or share a shopping list, but what if it had a screen for that? You know it’s important to stay hydrated, but couldn’t it be easier to keep track with a smart water bottle (Figure 6-1)?

Figure 6-1. Smart water bottles follow a classic upgrade approach (source: Hidrate Spark)

Upgrades often address problems for a tiny, affluent segment of the population. If you need an app to find a great restaurant, we’ve got you covered. If you’re a single mother, or an unemployed veteran, or barely making a living wage, you’re unlikely to benefit from the upgraded experience.

It’s not that eliminating problems, or even upgrading experiences, is a bad thing. But it often addresses one small piece of the puzzle, which means that it might stir up new problems or miss systemic ones. It favors solving a problem in the present, thinking less about the long-term impact of those quick solutions. And it tends to start with a solitary user rather than a system of intimately connected people, communities, environments, or cultures. At its worst, a problem-solving mindset can create an atmosphere of ambient dissatisfaction, in which everything begins to feel like a problem.

THE NEW NORMAL OF PRODUCT DESIGN

Whether we eliminate an unpleasant reality or upgrade an experience that is already quite good, we quickly adjust to the new normal. This idea, called hedonic adaptation, says that we have a thermostat that maintains a certain comfortable level of happiness. For each of us, our set point is a little different, but it means that even with highs and lows, we come back to that set point.

When that shiny new solution soon becomes same old, same old, designers and developers are tasked with the next improvement. And so goes a parallel universe hedonic treadmill for designers and developers, in which each new release is welcomed with appreciation for a brief moment before it becomes standard fare. Of course, this makes it extra difficult to look past the next version, much less 10 years out.

The limits of problem solving aren’t the only constraint we confront when we try to design for a further future. Automatic thoughts can color our beliefs and actions in negative ways. Called cognitive distortions, these are exaggerated thought patterns that perpetuate anxiety, depression, or other mental disorders. Cognitive distortions can translate to magnifying bad news or minimizing positive moments or jumping to conclusions. And it turns out that certain strains of cognitive distortions are particularly common among tech entrepreneurs.

CONFOUNDED FOUNDERS

Michael Dearing of the Stanford d.school met thousands of founders over the past decade, investing in seed-stage tech companies and advising startups. Over time, he began to notice and document distorted patterns of thinking common to this group. Dearing identified five recurring cognitive distortions based on his experience:1

Personal exceptionalism, in which the person sees their work or life or actions outside the bounds of their peers, permitting negative behavior.

Dichotomous thinking, which sees genius or crap and nothing in between.

Correct overgeneralization, by which universal judgments are made from limited observations but are seen as correct.

Blank-canvas thinking, which prompts people to believe that life is a blank canvas for their own original work of art.

Schumpeterianism, based on Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of capitalism as creative destruction, which leads people to see only the positives of disruption and too easily accept collateral damage that goes with it.

If you’ve worked in tech, these distortions might look familiar. And they run the full spectrum from Uber’s myriad missteps to SpaceX’s inspirational rocket launches.

Given that these are the filters that influence the tech industry, it’s easy to see how disruption came to be considered a universal good. Now, these cognitive distortions can certainly lead exponential change with the right idea in the right circumstances. Unfortunately, they can also lead to disruption without much care for consequences. Hubris rather than humility can result in disregard for long-term, far-reaching implications.

So, it’s not just methodological gaps but psychological barriers that must be overcome when we design a better future. Problem-solving steers us toward the short term; distorted thinking shifts attention away from long-term consequences. Artificial intelligence (AI) might make it even more difficult to move forward because it tends to warp time to create a near future that looks like the recent past.

THE TECH TIME WARP

In graduate school, I’d eagerly drive home for the holidays, excited to show my family how much I’d changed. I’d cultivated new friends, I’d learned about big new ideas, I’d discovered new music. But as soon as I walked in the front door, everything reverted to what it once was. Through no fault of their own, my parents didn’t know about the new me. They still treated me just as they did when I lived at home. Of course, that makes sense. That’s when they last knew my day-to-day habits, what I liked to eat, or the types of books I read. Even so, I dearly wanted them to acknowledge the new (better) me.

After arriving home, I found myself falling back into old routines. I watched TV, in contrast to the new me, who displayed a wall of broken TVs as an ideological statement. I dutifully recited my grades to distant relatives, rather than engaging them in debates about existentialism. Expectations from the recent past haunted my present and shaped expectations for my near future.

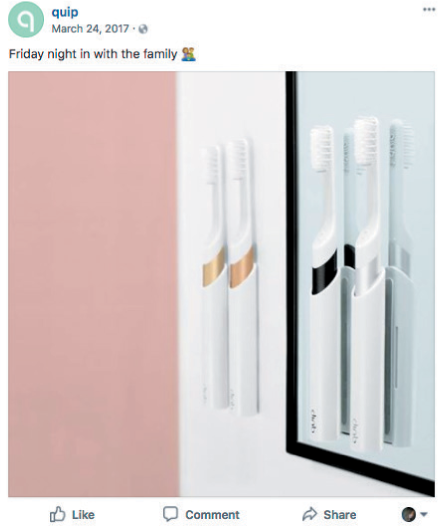

AI can create this same effect, capturing trends in our behavior (and soon our emotions) from the near past and projecting them into the near future. We already see glimpses of this phenomenon. I’ll see an ad for that connected water bottle. LOL, that’s “book research” me. There are posts with animal rights stories. That’s on the mark. Then, there’s the ad for the Quip toothbrush, which I can maybe attribute to buying an electric toothbrush for my spouse a couple of years ago (Figure 6-2). Harmless, but also a bit annoying.

Figure 6-2. It’s one thing to make dental hygiene a part of our future, quite another to let it define me (source: Quip)

At scale, it looks a little different. It might mean that as a woman I see ads for jobs that pay less because salaries for women have been lower. Predictive policing software ends up perpetuating disparities in communities of color by drawing on datasets from the last decade, for example. Because machines learn on our recent past data, time shifts just a little backward. It’s difficult to really move forward if we’re being pulled toward the past. There’s little room for us to grow or change or overcome expectations.

Even though technology is practically synonymous with the future, it has trouble taking us there. Design method, startup mindset, and even the underpinnings of tech itself conspire to make future thinking more difficult. Recently, a new field of affective forecasting has begun to look at how we make choices by looking at how we predict they will make us feel in the future. Here’s where we can begin to build a new approach to future forecasting.

A Future Fueled by Emotion

In the tech world, we pay a lot of attention to the present. How well do we deliver right now? What delights when people directly engage with the app? How can we get people to stay longer?

Boosting happiness in the moment goes only so far. Surprise and delight might soothe hurt feelings, but they haven’t created emotional durability. We can enjoy that confetti moment, and then have it be ruined by a lousy ending. People delete more apps than they keep, they switch between 10 tabs as they plan a trip and then forget about all of those websites after they’re done, they have a positive interaction with a chatbot, never to try another conversation.

And, of course, we adapt to what once made us happy. We discover a new app, and we are happy for only a short while before we want something else. These aspirations apply to our industry leaders, too, of course. We have a million users; let’s celebrate. OK, now let’s get more.

If we want to be happy in the moment, there’s something to be said for savoring it, trying to expand those good things (as we did in Chapter 5). But, mostly, we won’t be satisfied with living in the moment. According to Daniel Kahneman, in Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2011), our experiencing self is only one part of the picture. Happiness is just as much remembering as it is experiencing.

ROSY RETROSPECTION

When we look to the past, we often see it with rose-colored glasses. Simplifying and exaggerating memories might just be how we are able to remember in the long term. Rosy retrospection can be a good thing. It’s a kind of coping mechanism to remind us about the good things in our lives and about ourselves. A host of studies have shown that nostalgia can improve mood, counteract loneliness, and provide meaning.

It creeps up on us, too. As we age, we experience a reminiscence bump in which the events that happened to us from ages 10 to 30 seem best of all. Our most vivid memories are emotional events, and this period of our lives is particularly rich with them. Emerging identity, biological and neurological growth, and a concentration of important life events like college, first jobs, or marriage make memories from this period especially significant. I wonder if this isn’t why we are seeing a resurgence of nostalgia for the early days of the internet (Figure 6-3), including everything from quirky Web 1.0 conferences to a host of excellent memoirs2 to the new brutalist website design trend.

Figure 6-3. An internet reminiscence bump; remember the 90s? (source: FogCam)

Now it might be that this only recently discovered reminiscence bump becomes a thing of the past anyway. It might flatten out with fewer people reaching emotional milestones in one concentrated period. People are going to school, starting new careers, getting married, having children, and buying homes all over their personal timelines. Milestones are shifting, just as many people are intentionally deciding not to do any of those things at all.

When the past—or what we remember of it—seems so lovely, it becomes more difficult to imagine that the future will be better. The belief that society is headed toward a decline is an emotional self-soothing strategy in a way; it helps us to feel better about the present.

FUZZY FORESIGHT

Old-school psychology is obsessed with the past. Sigmund Freud hoped that people could cope well enough with the past to live lives of “ordinary unhappiness.” Some days that’s enough, but am I wrong to hope for more? Modern pop psychology tells us to stay in the present. Cognitive behavioral psychology aims to reprogram our present behavior. Mindfulness is the latest present-focused obsession. Definitely emotional skills to master, but how do we imagine what’s next?

Two new waves in psychology, both related to positive psychology and the study of positive emotion, are concerned with time-hopping to the future. That’s where we’ll take heart.

Prospective psychology studies the human ability to represent possible futures as it shapes thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. And prospection—planning, predicting, developing hypothetical scenarios, daydreaming, evaluating possibilities—itself is fundamentally human. We’ve already noted that emotions are not only a combination of evolutionary instincts or culturally informed concepts, but also a way to guide future behavior. Prospective psychology starts to study just how this might happen.

Rather than processing our past pixel-perfect, we continually retouch our memories. We are drawn to focus on the unexpected. We metabolize the past by remixing it to fit novel situations. These memories, in various combinations, propel us to imagine future possibilities as well.3

Prospection isn’t just fundamental to our thinking; it seems to contribute positively to our emotional well-being and mental health, too. One study asked nearly 500 adults to record their immediate thoughts and moods at random points in the day. You’d think these people would have spent a lot of time ruminating, but they actually thought about the future three times more often than the past.4 And they reported higher levels of happiness and lower levels of stress when they were thinking about the future.

The power of prospection is thought to be unique to humans, although I wouldn’t be surprised if that was disproved in the future. Neuroscientist Jaak Panskepp (Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions [Oxford University Press, 2004]) found that all mammals have a seeking system. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to reward and pleasure, is released when we try new activities and seek out new information. So, the act of seeking itself is ultimately rewarding. Casting about for the future might just be fundamental for all mammals.

Prospective psychology says that the future guides everything we do, and that it can make us feel hopeful (or not) about the future. Affective forecasting tells us that we use feelings as a way to predict the future for ourselves every day. Based on the work of Dan Gilbert (who coined the term) and Timothy Wilson, affective forecasting looks at the tiny shifts toward the future we make every day.

Big decisions, everyday behaviors, relationship choices, and all kinds of other important aspects of our lives are guided by how we think we will feel. We constantly make guesses about how imagined future events will influence our emotional well-being. When we make choices about where to live, who to marry, and even what to buy, we choose based on how we think that choice will make us feel. As it turns out, we’re terrible at it.

There are reasons, of course. For one, we conflate the details. We think a dentist appointment will be awful, and then it’s not so bad. The problem is that as soon as our minds get to work imagining the future, we leave out important details, like the nice person at the front desk in the dentist’s office or the whimsical mural on the ceiling. This focusing effect happens when we place too much importance on one aspect of an event, making our future predictions go awry.

Sometimes, we fail to appreciate the intensity or duration of a future emotion, thinking that a vacation will bring us more pleasure than it actually does or that the anger of a messy breakup will endure. For our purposes, it might be when we think we will not feel as upset by a thoughtless comment as we end up feeling. When we misjudge the emotional impact of a future event, this is called impact bias.

We underestimate how much we will adapt. Called immune neglect, we have a difficult time imagining how we will cope with things we perceive to be negative. You might, for example, overestimate the emotional consequences of an operation or the aftermath of identity theft. Discussions around work and automation amplify immune neglect, when we imagine a world in which humans will be extraneous.

We underestimate how much we will change. When I think about the future, I also don’t consider the fact that I’m going to be a different person in the future—someone who might want a minivan instead of a convertible. Even though we recognize our own personal growth, we can find it difficult to imagine that we will continue to grow significantly in the future. This is called the end-of-history illusion, in which we imagine the person we are now is the final version, the culmination of our personal growth.5 Seems like algorithmic decision making is founded on the end of history illusion as well.

We underestimate how much we will rationalize. After we do actually make a decision, we often end up wondering how we could ever have dreamed of choosing the other choice. When you’ve made an irrevocable decision, you rationalize it. When something’s gone and gone forever, the mind gets to work figuring out why what it got is really better than what it lost. This one seems to lack a catchy cognitive bias label, so let’s invent one: affective rationalization.

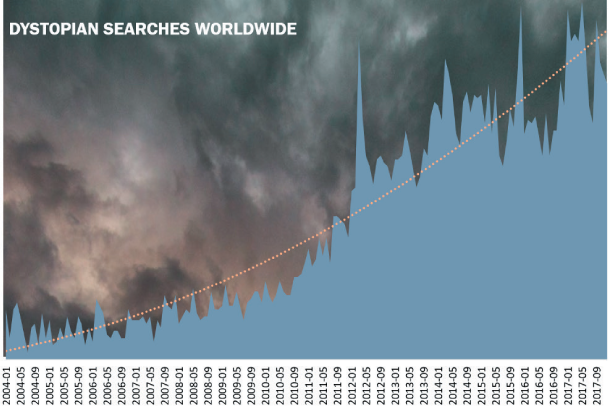

So, we are not just terrible at predicting what will make us happy in the future, we are terrible at it in all kinds of ways. We are a bit better at forecasting what will make us miserable than what will make us happy, but that might be because we have a negativity bias (Figure 6-4). Could this be why we see more dystopian futures in media and movies? Possibly. If it’s easier to predict the negatives in our personal lives, it seems like shaping doom and gloom futures might come more readily, too.

Figure 6-4. Are we wired for dystopian imagination? (source: GoogleTrends)

Technology is designed by flawed humans who often fail to recognize, understand, label, express, and regulate emotions. Now we find out that these same well-intentioned, emotionally-not-quite-that-intelligent (well, of course you are, but I’m talking about everyone else…) humans are lousy at predicting how future life will make them feel. Yet paradoxically, they are guided toward the future by feelings. In a way, what could be more human?

Knowing all this, how can designers, developers, and the entire cast of characters involved in the design of our internet things make wise choices about the future? Maybe it’s by just being rational. Forget about emotion. Oh, too bad that’s not really possible. Maybe we should let the machines design themselves? Oh, except they are trained by flawed predictors (aka humans) on flawed data about the same humans. No go. A more realistic choice, then, is to get a little better at imagining the future by getting better at tuning in to emotion. Let’s see if we can design interventions to improve our emotional forecasting skills. First step, get personal.

Start with Future-You

Imagining future-you is not so easy. Maybe you think about dinner this weekend or maybe you set a goal to purchase a bike next summer. Imagining the far future is even more challenging. Try to vividly imagine yourself in a world 20 years from now, and it’s easy to fall into platitudes about jet packs and flying cars. For our personal lives, we might imagine (on a good day) working less, traveling more, really enjoying our lives. Beyond that, it’s fuzzy.

Our future selves are literally strangers to us; at least, that’s what neuroscience tells us. The further out in time you imagine your own life, the more your brain begins acting as if you were thinking about someone else. This glitch makes it more difficult for us to take actions that benefit our future selves as individuals and in society. The more you treat your future self like a stranger, the less self-control you exhibit and the less likely you are to make pro-social choices. You’ll procrastinate more, you’ll put less money away for retirement, you’ll skip the gym. As UCLA researcher Hal Hirschfield put it, “Why would you save money for your future self when, to your brain, it feels like you’re just handing away your money to a complete stranger?”6 When you can’t imagine yourself in the future, your decision-making suffers.

When your future self is a stranger, it affects society, too. Legislators who undo regulations to mitigate long-term climate changes in exchange for short-term gains, and policy makers who say workplace automation can’t be fathomed because it is years away, fall into this same trap. A large part of the population will be alive in 30 years to feel the impact of climate change and see the changes that AI will have on the workforce. But we have trouble imagining just what that future will look like and how we might influence it.

Clearly, we need to get better at feeling the future. Yet, putting ourselves in the future doesn’t come easily. So, if we want an emotionally intelligent future with technology, it makes sense to practice first-person futures.

PERSONALIZE THE FUTURE

A typical future forecast might be, “By 2050, sea levels might rise by as much as 9 feet and 750 million people will be displaced.” You’re apt to feel unmoved by a statement like that. A speculative design piece might respond with a video about an amphibious living pod. Thought-provoking, uncomfortable, but a tad too fictional to be deeply felt. Or maybe too fully realized like good sci-fi. That doesn’t always leave us a lot of room to imagine ourselves in that future.

Now let’s translate this to a design thinking–style future workshop and it looks like “How might we offset a rise in sea levels in 2050 NYC?” Rather than a predetermined outcome with a fully realized response, it’s a problem to be solved. Certainly, we will take individuals’ lives into account, but that takes a backseat to the product or service we are tasked with creating. Perhaps knowing that people will need to move, we will work with the city to create more multifamily housing space. That’s a good start.

What if we enriched the challenge by making it personal? Now, a persona might get us there, especially if we’ve layered in emotion. Simply inserting a human being helps us to imagine the future more vividly. But if it’s someone else, especially a theoretical someone else, it still keeps emotion at arm’s length.

Instead, we might frame it like so, “I’ll be 72 years old in 2050. The two airports I currently use will be under water. Flying will be less reliable, so I might live closer to my extended family.” Future-you is bound to stir up more feeling. And to adopt affective forecasting as our model, we need to actually feel the future.

Personalizing the future builds empathy toward our future selves. More than that, it is a meaningful way to envision the future. Given that we make predictions for our future selves based on how we believe we’ll feel, shouldn’t we begin by asking questions about future-you?

PRACTICE COUNTERFACTUAL THINKING

In a recent study, the Institute for the Future found that the majority of Americans rarely or never think about the something that might happen 30 years from today.7 When futures loom a little closer, people are more apt to think about those possibilities. If you’ve had a brush with mortality, you might devote a few more brain cycles to the future. When you have a child, you are more apt to engage in future thinking, too—as soon as you get past the sleep deprivation. Some people just seem to be more likely to engage in future thinking as part of their work, and I’d venture to say that people working in technology might be among those happy few.

Either way, this leaves us with a kind of future gap. Thinking about the 5-year, 10-year, and 30-year future is essential to being an engaged citizen and creative doer, but we need some strategies. Counterfactual thinking is one way to develop those skills.

Counterfactual thinking is the way psychologists describe how we create alternatives to our own stories. Although it can be a coping mechanism for trauma, it can be a strategy for positive growth, too. Thinking about how things could have been and how things could have happened is a method we can use to develop our futuring skillset.

In her 2016 Aspen Ideas talk, Jane McGonigal talks about predicting the past and remembering the future.8 Yes, the point is to mess with your head a little. By predicting the past, she means when you think about an event in your life and then imagine that you took a different path. For instance, maybe you chose to attend a different college or took a different job. That would be the starting point for a new path that reaches toward an alternate future.

Remembering the future is a technique to create something like a memory. You craft these future memories by using an XYZ formula, where X is an activity or event in your life, Y is a person, and Z is a place. The more detailed and personally meaningful, the easier it is to retrieve the “memory.” It’s a pseudo-memory of a pseudo-future.

As I’ve been running futures-thinking workshops with schools, community organizations, and companies, introducing counterfactual thinking works well as a warm-up. If we put these exercises together—predicting the past and remembering the future—it looks something like this.

First, invoke autobiographical memory. Use as much vivid detail as you can recall. You can also invent details as long as they’re personal ones. Let’s take, for example, a trolling incident on a social network. Think of what the troll said or did. How did you respond? How did you feel? What was the reaction of the community? Where were you when it happened? What else was going on around you? What, if anything, in the design itself was relevant to the experience?

Now reimagine the encounter from your own point of view. Ask “what if” to take it in a different direction. Here’s a obvious question: “What if you were speaking face-to-face?” But you might also ask, “What if I had done something else?” or, “What if someone else had responded like so?” Include as much personal detail as you can; invoking your talents and insights helps you to imagine how the situation might shift. Imagine how you want to feel.

Next, reimagine it from your antagonist’s point of view. Rather than portraying that persona negatively, try to engage empathetically. Look for ways to connect without sacrificing your own values, imagining that person’s everyday life, their upbringing. Next, imagine that person doing or saying something that’s positive. What facilitated that turn? Could the design support that? Frame “what if” questions around imagined possibilities.

In a way, we’ve just re-created Dylan Marron’s podcast Conversations with People Who Hate Me. We’ve rehumanized one another, counteracting the disassociative anonymity of online interactions. We’ve inverted the script by reconfiguring antagonists into partners. More than a positive behavioral or emotional intervention, it also gives us a path toward designing the future. Translate those what-ifs into design challenges, and the exercise generates alternatives. But let’s go further.

Take your relationship forward five years. What does it look like? What supported mutual understanding? How did the design help that relationship to flourish? How did it foster understanding in a larger community?

Finally, look at what might have happened if you went back in time and followed this new path. Create an emotional timeline, but this time start five years in the future and then work your way backward. Fill in a milestone—maybe it’s the admiration you felt when an influencer like Roxane Gay first used and shared the new video conversation option to engage with someone who had been trolling her. Introduce a mundane ritual, like when you began dialing up your EQ setting every time you looked at posts. Add a memory; maybe it’s that warm confidence you felt when you and your community coach met in-person after so many conversations on the platform. Let’s call this emotional backcasting.

Counterfactual thinking can help us look back on our own lives and explore a path not taken. It can also help us plant new “memories” that provide motivation toward positive goals. Another way to bend time is to reconsider the objects in our lives.

SORT THROUGH YOUR STUFF

Recently, I visited East Harlem’s Treasures in the Trash Museum. Nelson Molina, over a period of 30 years, developed an extensive collection of discarded things while working for the New York City Department of Sanitation. He began by saving items from his route to decorate lockers at the depot. Coworkers added to the collection. When the trucks were moved out of the garage to another location, the collection of rejected things took over the space. Today, there are more than 50,000 objects in the museum, grouped by color, size, or style. As you walk through the aisles of crystal and typewriters and photographs, you might wonder at how all these objects ended up in the trash. You might wonder at the story associated with each of those objects, and how they went from wanted to unwanted, from part of a life well lived to a life abandoned.

These are the stories we need to understand to move into the future. As designers and developers, increasingly making both physical and digital objects, we have to confront the idea that we’ve introduced objects into people’s lives that end up in the same place—the trash. So, to better imagine future objects, start at the end, with cast-offs, and move backward. This is the future we once wanted; now it’s a past we disavow.

How do we decide which things keep their value and which become trash? A few exercises can work through it:

- KonMari sort

We might be past the “spark joy” craze of Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (Ten Speed Press, 2014), but the impulse toward clearing out the old and starting fresh remains relevant. More important, this method has something to tell us about our emotional life with objects. The theory here is that we hold onto things, digital or physical, due to fear of the future and nostalgia for the past. Things trigger our affective forecasting spidey-senses.

The idea of a KonMari sort is to hold up each item you own and contemplate whether it delights. It might sound a bit gimmicky, but the idea behind it is useful. Take a minute to contemplate your emotional connection to the object. If there’s none, off it goes. If there’s something there, think again.

Discerning whether objects spark joy in the moment can fail to appreciate the layers of meaning objects accrue, or how our emotional relationship with objects waxes and wanes, or the complexity of emotion. But it does encourage us to shift perspective, slow down, and contemplate that relationship. Whether digital or physical objects, this technique works just as well in an interview as a workshop by encouraging people to take emotional stock.

You can start your own emotional inventory with a list of three technologies (or any objects) that spark joy. If you are looking to innovate in pet care, limit it to that space. If you already have a pet-care product, make an emotional inventory of features instead. It doesn’t need to be “spark joy,” strictly speaking. It could be “things you feel strongly about” or “tech that you associate with [emotion].” The point is to get right to essentials.

- Emotional laddering

Asking people for an emotional reaction is a shortcut that transports us to deeper questions right away. But we can go further with it, given that people often describe emotion in broad strokes especially when they are talking to people they don’t know very well. Just as we might use laddering (similar to the five whys) to explore the true goal behind the action, we can use that initial “spark joy” prompt to gain insight into the emotional underpinnings moving from attributes to consequences to values. The conversation might look like this:

Q: What about your dog tracker makes you feel happy?

A: The video feature lets me see my dog during the day while I’m at work.

Q: What is important to you about that?

A: It makes me feel like I’m there when I can’t be.

Q: And why is that important?

A: My dog has anxiety, so I worry about him after I’ve been gone for a few hours. That usually kicks in mid-morning. I’ll admit that I’m a bit worried about my favorite chair, too.

Q: So how do you handle that?

A: I’ve been working with a trainer on it.

Q: When was the last time you saw your dog getting anxious?

A: Just yesterday, as I was commuting home.

Q: How did you know?

A: I always check in on the way; it’s just something I do. But I find myself just checking it a lot throughout the day.

Q: So, what did you do?

A: Well, not much. I felt like there wasn’t anything I could do, but it did make me feel in more of a rush to get home. I decided to skip picking up dinner.

Q: What did you do on the rest of the commute?

A: I was glued to the screen, feeling worse by the moment.

Not every interview will reveal dog feelings, but you see how you can use this technique to get specific on a range of feelings in unexpected trajectories. What started with a big category and ended in a mix of feelings including anxiety, worry, comfort, relief. This technique showed us some of the actions that those feelings spawned, from rushing to reaching out for support to not having a way to take action at all. If these aspects of the experience aren’t addressed, the relationship will suffer in the long term.

This technique revealed aspects of the experience that need design support, perhaps timed check-ins. If we are paying close attention, it shows us where we should help people disengage, so that our dog’s human doesn’t feel tethered to the device. Feeling overwhelmed, addicted, and increasingly anxious is a certain path to drive people away. And it uncovered new areas of opportunity, like sharing video clips with the trainer or on-demand coaching or even an emotionally attuned chatbot.

Now back to the future. We’re time bending, after all. Let’s try using this technique to move backward and forward in time.

Q: When was a time you felt happy with this tracker in the mix?

A: I remember this one time. I was in a meeting that was running long and I was able to check in on my phone, under the table of course. It felt like a little secret between me and my doggo. Well, and my colleague, who noticed it and, you know, my Instagram followers.

We could ask the participant to sketch what the next secret moment might look like or ask about other secret moment in any context for an analogy to draw from. Going forward, we could look at ways to embed more of these secret (or not-so-secret) moments into the experience. Maybe a cheeky nod that we are in on the secret, maybe a secret stream of other secret moments.

Q: Imagine a year from now and you no longer have this tracker.

A: Nope, not going to happen.

Q: Why is that?

A: Now that I have this view on my dog’s world I feel like I have a closer connection.

Q: To your dog?

A: It’s weird, but I think it might have changed my attitude toward work. I think I have more compassion for colleagues who are late or leave early or aren’t always available.

Q: What if it kept going that way?

A: Maybe we need to bring more of our world with us to work? Or maybe we already do, but we just don’t know it.

One emotion has expanded into a rich collection of feelings, each opening up a new possibility to sustain a fulfilling long-term relationship with the customer. It’s also uncovered a world of other possibilities. Compassion for coworkers, shared secrets to bond with one another, and the feeling of calm and comfort that probably inspired the initial design. Finding the emotional resonance of the past helps us to project it into the future.

- Trash track

Photographer Gregg Segal’s series “7 Days of Garbage” show friends, neighbors, and strangers lying in a week’s worth of trash. Every time I see it, I’m horrified imagining myself and all the trash my family produces in a week. That’s the desired effect. We can take it a step further as a design exercise, though. Take a week and try it yourself, physical and digital. You’ll likely identify a few different types of cast-offs.

First, you’ll uncover freebies, giveaways, bargains, packaging. Lots of things you never asked for, from junk mail to junk email. Even the items that you feel you must keep just in case, often files and forms. This is the first layer. Let’s hope that your product isn’t in this category. The emotional weight of this type of trash is low, but as it accumulates, it can become a burden. This is why, for some people, seeing a high number in that red notification bubble is anxiety producing and why inbox zero is a lauded achievement. A few junk items are low-level irritants; at scale it’s debilitating.

However, you need to go further if you are looking for emotional relationships. As you sort through the rest, you’ll find three kinds of trash: trash that reveals your identity, trash that is connected to other people, and trash that represents how you view the world. If it’s intentionally dumped, it’s your past. And it implicitly frames your new hopes for the future.

Starting with identity cast-offs, trash that reveals who you were and who you want to be, you’ll first find the aspirational—things that signify who you wanted to be. Maybe you purchased a fancy set of barware because you want to be the person who brings together friends for intimate dinner parties. When you give it away, are you being honest with yourself, setting new goals, or disappointed that you haven’t achieved what you aspired to? In Happy Money: The New Science of Smarter Spending (Simon & Schuster, 2013), Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton found that experiences give us more long-term happiness than things. When it comes to things, objects that help us do activities we love, like tennis rackets or musical instruments, make us happy. We’ll cast these aside as we change what we want to do. The multiple social media profiles that teens adopt and discard would be a virtual example.

Transitional trash is a time-hop we can make with trash. Psychologist Donald Winnicott introduced the concept of a transitional object, something that stands in for a person or even a feeling. A blanket or toy fills in for the parent relationship, but at a certain point most kids no longer need it. Adults attach to transitional objects, too, for emotional well-being to self-soothe. Is it cast off because the relationship has changed? Or the context has shifted? Or it’s become associated with something else over time? Or it’s no longer needed?

Then, there are the items that transport you back in time, nostalgic trash. It could represent a person you love, from a joyful moment to a regretful one. It could symbolize an entire period of your life. It could stand in for a place. Whatever the case, this is an item that you cherish for its power to transport you to a better time. When you give it up, it could mean you’re ready to move on. Or you’ve changed what you value. Or your memories have shifted.

Obviously, there are certain to be other types of objects that you’ll find in the trash (or that you want to save forever). Little treats in the form of small purchases can also create an intense but fleeting form of happiness. In a fit of pique or inspiration, you might get rid of things and then come to regret that, too. Our relationship with objects, physical or virtual, is subject to intentional changes as well as whims. It’s very human to feel torn between wanting to change everything and become a new person and feeling extremely nostalgic for everything that’s ever happened.

In truth, many objects are designed to become trash. Electronics, or items with embedded electronics (like cars or toasters), are unfixable. Fast fashion, whether clothing or home items, ties obsolescence to style. Even virtual objects, apps, and websites are obsolete as soon as they launch. Industry-wide, the decision as to whether to create objects for emotional sustainability merits urgent discussion. Until then, we can start to sort out the emotional relationship by contemplating how yesterday’s treasures become tomorrow’s trash.

- Time capsule

After examining what we’ve trashed, it’s time to think about what we’d save. If you ask, most people would probably say they’d save their most valuable possessions, both economically valuable objects and personally valuable ones. These grand milestone markers and treasured purchases might make us happy in the future, but perhaps not as much as we’d like to think. Revisiting ordinary, everyday experiences can bring us a lot more pleasure than we realize.

Researchers at Harvard Business School recently studied what happens when people rediscover ordinary experiences from the past, when they asked students to create time capsules.9 Participants were asked to include the following items:

A description of the last social event they attended

A description of a recent conversation

A description of how they met their roommate

A list of three songs they recently listened to

An inside joke

A recent photo

A recent status they had posted on their Facebook profile

An excerpt from a final paper for class

A question from a recent final exam

For each item, participants reported how they expected to feel upon viewing it three months later. They then completed the same set of ratings when they actually viewed the time capsule three months later. Most vastly underestimated how strongly they would feel about viewing those items again. Of course, you might know this already just by scrolling through your old photos or revisiting a Facebook memory. Even the most mundane detail, what you were wearing or a favorite catchphrase, can captivate.

So, rather than assessing emotional value by what we are willing to move past, let’s launch our cherished possessions and mundane moments into the future. Choose several objects for your personal time capsule. Or write a letter to your future self (Figure 6-5). Your time capsule might also include objects with an emotional value, as you found when you tracked your trash (or what you couldn’t let go). Think about how you would choose the items. Predict how you will feel about them next year, or five years from now. Consider whether the meaning they have now will likely change over time. Then, tuck it away for a while. Let me know what happens.

The idea behind all these activities is to pay attention to the emotional relationships we have with our objects and how it lets us time hop, moving from past to present to future, and back again. The more skilled we become at emotional time travel, the better we will be at predicting how products and services will make us feel, individually and collectively, a few years out. The next step is to create future objects to fathom our future feelings.

Figure 6-5. Your future self will appreciate the most mundane details (source: Futureme)

Create Future Things

Speculative design, with its focus on designing objects that prompt conversations, can help us explore how we might feel about the future. Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby call these props. “Speculative design props function as physical synecdoches, parts representing wholes designed to prompt speculation in the viewer about the world these objects belong to.”10 In other words, for people to see themselves in the future, the abstract must be made tangible.

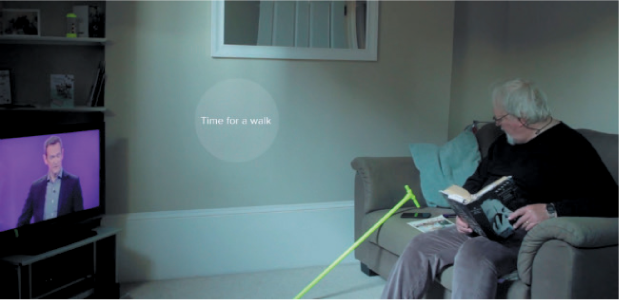

Design studio and research lab Superflux, led by Anab Jain, explores the uncertainties of everyday life and emerging technology in just this way. A good example is Uninvited Guests, which shows frictions between a man and smart objects in his home (Figure 6-6). The brightly colored objects in the film are placeholders to show the tension between human and machine. The film pictures a near future in which devices offer elder support, as an extension of family or caretakers. The short film lets us feel the individual conflict. Here, design can nudge us toward predicting how we might feel.

Figure 6-6. Yes, we have feelings about this future (source: Superflux)

Speculative design gives us a framework to place new technological developments within imaginary but believable everyday situations. When future objects walk among us, we can better debate the implications of different technological futures before they happen. Speculative design is purpose-built for uncomfortable conversations. But it can prompt more than critical reflection. It can awaken our senses. It can help us to imagine how the future feels.

So how do we take speculative design out of the academy or the art house to evoke future feelings? Let’s take everything we’ve learned from affective forecasting and apply it here. Time hop from past to future and back again. Practice storytelling in vivid detail. Above all, make it personal. Next, let’s broaden the scope to look at future traces in the world around us.

SCAN FOR SENTIMENT SIGNALS

Science fiction writer Octavia Butler drew inspiration from what she saw on the streets. She’d walk around the poorest areas of Harlem and take note of every problem she saw. Then, she’d try to address them in her fiction and examine the implications. Speculative designers do the same, scanning the world for leading-edge examples of a local innovation or a new practice that could be translated into future products that provoke an emotional reaction.

Maybe you’ve wondered where to look for signals of the future. Future forecasters say they are crunching the numbers, but it still seems rather mysterious. In the marketing world, trendspotting is a closely guarded secret. Speculative designers tell us to look around for trends, without much mention of how they sort through the noise. The real secret is that there’s no magic to it. It’s a combination of spotters, or people all over the world who observe in-person the new and unusual, and scanners, who are sifting through reports of the new and unusual. Primary research and secondary research. Think of it as crowdsourced ethnography.

We’ve already started by looking for clues among our own objects. Now we look outward. Begin with a range of sources, a mix of academic and pop culture, news and fiction, personal and policy:

News that reports on or analyzes relevant trends, from a variety of sources—even ones that make you uncomfortable and maybe even those you find questionable.

Conferences, festivals, and events often posit potential futures. CES and SXSW might be obvious examples, but plenty of other conferences will be the first place where people try out ideas. Video, decks, posts, and social media reaction are all fair game.

Patents and trademarks. If there was ever a place to analyze future intent, it’s sifting through patents related to your topic.

Kickstarter and other crowdfunded creative platforms.

Policies, national and international, from governing organizations or advisory councils might be scant or tangential. Academic committees, think tanks, or nonprofit groups might publish position papers or recommendations that can fill in the gaps.

Public datasets, whether with visualization tools built in or not, can help us get to know trends. Gapminder, Google Trends, Facebook Graph, Data.gov, and Pew Research Center, among others, are good resources to get started.

Fictions intentionally or tangentially describe a future relevant to the discussion. This includes not only short stories or novels, movies, and shows, but also Tumblr blogs, Twitter microfiction, and even nonfiction pieces that include fictional scenarios. Fictions can be contemporary or historical, too.

Original research includes qualitative interviews and ethnographies as well as social listening, surveys, and other quantitative research.

Random acts of design collect ways in which people adapt the environment to their needs. IDEO’s Jane Fulton Suri categorized these as reacting, responding, co-opting, exploiting, adapting, conforming, and signaling in her book Thoughtless Acts (2005).

The DECIPHER model (from Chapter 3) is worth revisiting, too.

Signals will likely be a mashup of mundane predictions, negative trends, positive spin, wild speculation, imagined product benefits, whitepaper recommendations, and hopefully some tales of everyday living. At my firm, we organize trends by broad themes like Algorithmic Living or Mixed Reality and also include tags, quotes, and cross-references. Small moments and specific examples are nested inside larger trends.

What if we took it further, though, and tuned into the emotional resonance of these signals? Because we know feelings are the way we predict the future, it makes sense to pay attention to them. You could get an initial read on sentiment by text-based sentiment analysis where it’s relevant. If you have a body of publicly available comments on a news story or are working with records in a public dataset, this can be a good way to start. But we know that any kind of automated emotion-reading is only a first pass; it lacks nuance.

The Geneva emotion wheel or an adaptation can identify the signals with the most emotional impact (Figure 6-7). It’s been used to measure emotion in music, to sort out emotion in tweets about the Olympics, and as a way to train AI. For example, if we say your future signals are around health hacking, you could create an emotion graph for leading-edge trends like brain hacking pills, ketogenic diet apps, and self-administered vaccines to understand which ideas inspire strong feelings.

Figure 6-7. Sorting out signals with an emotion wheel (source: Klaus Scherer)

Now we have the emotional rough-cut. Next, we need to make the future personal and real.

STORYTELLING STRING THEORY

An empathetic leap of the imagination can be as simple as some alternative reality storytelling. Stories can convey powerful emotion, but they also help us to sort out our own feelings. Whereas designers tend to tell tales of ideal pathways, whether a hero’s journey or a continuous loop, for the sake of the future let’s tell stories of all manner of parallel realities so that we can sort out how we feel about each one. Here are a few ways to try:

- Day in the life

- Tech writer Sara Watson plays around with a narrative that begins with her refrigerator denying her access to a favorite IPA and an autodelivery of groceries including prenatal vitamins. Her internet things somehow think she’s pregnant and she’s not quite sure what tipped them off.11 The very personal story strings together a series of current, near-future, and fictional products from news stories and Kickstarter projects together into a plausible future, and one with emotional force.

- Fast-forward personas

- The story of a fictional person can prompt feelings, too. Recently, UK innovation foundation Nesta shared short stories inventing “Six Jobs for 2030.” Amit, the 100-year counselor, teaches and coaches people through career transitions as lifespans grow longer. Lisa works in green construction, pushing clients to take the long-term view of their green investment. More than personas that sketch demographic details, nifty graphs of purchase histories, and quick lists of typical behaviors, these well-crafted stories help translate trend signals into emotional signals.

- Invent a ritual

- Rituals take a moment in time and stop it, extend it, reflect on it, fill it with new meaning. Ritual not only lets us understand emotion and build meaningful relationships, but also bends time. So, it makes sense to add ritual to our future-forecasting repertoire. You might begin by making an inventory of the rituals in your own life. Maybe you make your bed in a certain way every morning or you breathe deeply several times before heading into your home at night. Consider when these rituals come into play, mapping out a routine. Look for emotional peaks or valleys as a clue for when to intervene. What are those moments that are worth expanding?

- Museum guides

- In A History of the Future in 100 Objects (Amazon Digital Services, 2013), Adrian Hon writes from the perspective of a museum guide for the near future. Organized as a timeline of the 21st century, the book describes everything from ankle surveillance monitors (2014), to a multiple autonomous element supervisor (2039), to neuroethicist identity exams (2066). Rather than narrating histories about people, the idea here is to narrate histories of the object itself.

- Social media futures

I’ll confess to borrowing from a common middle school history class assignment: creating a social media profile for a historical figure. Mikhail Zygar takes this exercise to the next level, using real diaries and letters to create Project 1917, revisiting the Russian revolution through social media (Figure 6-8). His latest project, Future History: 1968, retells the story of the era in texts and Snaps of historical figures like Eartha Kitt and Neil Armstrong.

Figure 6-8. If we can transport the past into the present, why not the future? (source: Project 1917)

For our purposes, we won’t attempt a Facebook page for Abe Lincoln or a Twitter profile for Marilyn Monroe. Instead, imagine someone famous or not-so-famous posting about the idea you are exploring, but five years into the future. You can even set up a social media account and involve the team in developing the persona and the responses from the community. If we are looking for emotional impact, social media is where emotions already run high.

- Four worlds

- Future forecasters often use a four-world model. In my speculative design class, we rely on an adaptation of a common model known as Four Ws: weird, worse, wonderful, whatever. PwC’s Workforce of the Future Scenarios delineates four future scenarios to show paths that could diverge or coexist.12 The Blue world is dominated by big corporations, the Red world by innovation, the Green by sustainability, and the Yellow by humans first.

The same holds true for emotional experience. Think of Patrick Jordan’s model (mentioned in Chapter 2) of the four quadrants of pleasurable experience. Nicole Lazzaro’s model for gaming, based on an ethnographic study of gamers, distills the best gaming experiences into four types: hard fun (challenges), easy fun (immersion), serious fun (personal growth), or people fun (social).13 Each develops four archetypes of emotional experience. We can revisit the four emotional worlds from Chapter 3 to create future scenarios. Our four worlds, if you recall, are as follows:

Transformative, experience that facilitates personal growth

Compassionate, altruistic and prosocial experience

Perceptive, sensory-rich experience

Convivial, experience that brings people together socially.

For each future concept, from a big idea like an emotionally intelligent city block to something narrower like personal financial health, develop stories for each of the four scenarios. Who thrives and who doesn’t? What new practices flourish and which ones fade out? Consider what that world looks like at first, and then five years further.

Telling stories from the signals we collect is one step toward creating future things. Whether we imagine a personal day-in-the-life or a history textbook, a story will help us feel the future. The next step is to imagine a world with that future thing already in it.

CRAFT A CONTEXT

In 2009, Rob Walker and Joshua Glenn started an experiment called Significant Objects. They purchased thrift-store objects and asked contemporary creative writers to invent stories about them. Then, the objects, some purchased for only $1, were auctioned off on eBay for thousands. Context really is everything.

To understand the feelings around a future object, sometimes we don’t even need an object. Unlike the typical design prototyping process, in which we rough out sketches and iterate, instead we skip to the end and create an object that points to your future object as if it already exists. Yes, it’s meta.

Props leave room for the viewer to imagine. This is a bit different than current design practices. In a co-design, we might ask people to assist in creating a concept. In a usability test, we ask people to interact and sometimes critique. Here, we create a thought experiment instead. The goal is to create a way to bring the story to life.

This could be a guidebook, a catalog, user manual, newspaper, unboxing video, user review, even a patent. An FAQ could include questions that came up in writing the press release, but the idea is to put yourself in the shoes of someone using the future product or service and consider all the questions. Press releases are a rarity these days, but they have a well-defined format that can help describe what the product does and why it exists. Amazon popularized this approach, creating press releases for new features rather than presenting long slide decks to executives.

Other examples of “legit” fictions to go with the object abound. Specify your fictional object with a patent, including schematics and prior references. What if it has already gone quite wrong? Perhaps a legal petition. What if the object has become obsolete? Perhaps we create a museum plaque or exhibit. Or perhaps we stumble on it as a souvenir. Or maybe it ends up on a list of items that can be recycled. Any way that the object might be appropriated by people in a mundane context is fair game: a teaching tool, a recipe, hobby gear, a yard sale, an artwork, a screenplay, a news article, a classified ad, or an auction description.

This is a way to pay attention to nefarious uses of technology. How might the product be hijacked, misused, or trolled? Who is likely to do so? How bad are the consequences? Create a pirated version or imagine how it could be used for prison contraband or, worse yet, weaponized. For our purposes, consider how it might negatively affect mental health. Will it drive compulsive behaviors? Will it erode social norms? Will it undermine relationships?

No matter the prop, the context should feel like everyday life, but a few years or decades forward. Situating the design fiction, whether it has an object to go with it or not, in an unscripted environment is a sure way to get at the emotional impact. Near Future Labs, for example, created the IKEA catalog of the future to portray products from a few years forward (Figure 6-9). Obviously, we need to take care. Setting up a pop-up shop, as Extrapolation Factory did with 99 Cent Futures, is less risky than trying out an artifact in a doctor’s office where its placement might mislead and have real implications.

Of course, the prop itself guides how we might dramatize it. A speculative patent document might be couched in a simulated patent search. A fictional unboxing video might be best viewed on YouTube. You might have noticed that many of the speculative design projects listed here imagine an object that we have bought or a thinking about buying. That makes sense because we are making products or designing services to buy. It doesn’t have to end there.

Figure 6-9. It feels real; now how does it make you feel? (source: Near Future Labs)

Futurists often use the STEEP (Social, Technological, Economical, Environmental, and Political) framework to explore trends or develop implications. I use a variation, influenced by global well-being indexes, like the Social Progress Index, Gallup Healthways, and the Global Happiness Index. THEMES (Technology, Health, Education, Money, Environment, Society) is a small tweak that ensures we focus on the most meaningful aspects of personal and collective experience. We can then use it to inspire new dramatizations for our imagined future objects.

- Technology

- Embed, upgrade, develop, integrate, hack. Stage it as an accessory for another product, fictional or not. Say it is an upgrade to another product. Situate it on (faked) GitHub.

- Health

- Assist, care, counsel, diagnose, chart, advocate, volunteer. Show the data from the object in a medical history or chart. Role play its use in a hospital, or assisted living, or hospice. Prescribe it.

- Education

- Teach, study, plan, test. Use it in a syllabus. Show it being referenced in a mock lecture. Develop a study guide that includes it. Present it at a school board meeting. Create rules for its use at a school. Stage proposed legislation related to its use in schools.

- Money

- Sell, market, trade, review, pawn, give, price, promote. Resell it on eBay. Write a classified ad for it. Leave it at a yard sale. Set up a pop-up shop. Give it as a gift. Film a short piece describing the product as the next holiday craze.

- Environment

- Conserve, protect, contaminate, recycle, degrade, repurpose, dispose. Show how it degrades through three generations. Make a recycling guide. Dramatize how it is passed down through three generations. Write an investigative report on its role in damaging the environment.

- Society

- Regulate, legislate, celebrate, mediate, vote, debate. Stage a debate pro and con. Create a ballot to vote on regulations or restrictions. Set up an event for a user community. Plan an exhibit of it as an artifact from 20 years past.

Stories about the future that pay attention to emotion help us to imagine how we’ll make a life with future technologies. Fictional products can take it even further, so let’s look at some ways to make evocative objects.

MAKE A FUTURE HEIRLOOM

Every so often I receive a package that’s a jumble of photos, letters, and handwritten recipes from my mom. Sometimes, I have little memory of who’s in the photograph or where the recipe came from. Sometimes, there’s a flicker of recognition. I’ll recognize a bookcase from my aunt’s house, recall a picture I saw displayed on a dresser, or catch a hint of a scent that I maybe remember. The sensory experience of these artifacts being passed around the family made me wonder about what future heirlooms might look like.

A few heirlooms are created, or marketed, with the status of heirloom in mind, like a watch or a custom-made cabinet. There might be something intrinsic to the object themselves, like the materials, the details, a handmade quality. An heirloom is often associated with luxury, like the Kronaby swartwatch (Figure 6-10), but not always.

Figure 6-10. A smartwatch reimagined as an heirloom (source: Kronaby)

Many heirlooms were once a common object, maybe with a low life expectancy, that somehow lasted. Perhaps because they stand in for a person. My own daughters debate who will get my shoes one day, for instance, even though none are particularly expensive or well made. Perhaps they have accrued meaning over time. Whatever the case, heirlooms reveal what (or who) we value, and some of those values have a timeless quality. Heirlooms are the antithesis of the easy, the frictionless, the ultimately interchangeable products that we buy or borrow only to shed shortly after.

What makes a future heirloom? This was the premise of a workshop I held with design students. Students began with a think-alone activity, documenting an object in their own lives that they would consider an heirloom. How would you describe the sensory experience? What emotions are associated with the object? How intense are those emotions? Have they changed at certain times in your life? What are they like now? What does the object represent? How close is it to your identity or people you care about? What does it express about what you value? Students created stories, sketching and writing.

This prepared us to create a personal artifact that will be meaningful enough to pass on to future generations. It’s a design that is emotionally durable, as designer Jonathan Chapman describes in his book Emotionally Durable Design (Routledge, 2005). The next phase was to build these insights to create a future heirloom. Almost all the concepts bridged the physical and virtual worlds, blending luxury and every day, nostalgia and aspiration. One student invented a crystal hologram pendant that contained family member stories, a future living locket. Another prototyped a beautifully crafted bike handlebar that remembers music and replays rides and can be displayed as an art object.

Rather than focusing on solving a problem or making life frictionless, the heirloom prompt nudges us to go deeper. It challenges us to design a meaningful, resilient, emotionally durable product or service. An emotionally intelligent future for design must consider the lifespan of our products.

DEVELOP RELATIONAL ARTIFACTS

More than 100 robot dogs were recently given a funeral in Japan. With the last AIBO repair clinic closed and Sony no longer supporting the discontinued robot dogs, owners said goodbye in a service at the Kofukuji Buddhist temple. MIT professor Sherry Turkle coined the term relational artifacts to describe sociable robots like Sony’s AIBO robot dog. Think of it as something at once familiar (the dog) and unfamiliar (the robot-ness). In that familiar sense, the object is an extension of what came before. At the same time, they look forward. These are not just objects that we attach to, but objects to think with and to feel with. So, creating relational objects is another way to sort out future feelings.

There are two ways we can approach it. One is the way of speculative design, creating an object that shows us what the future will look like. Whether it’s a furniture collection that uses miniprojectors to display our favorite music or books or photos, or clothes that nudge us toward conversation, a physical object or digital experience gives us a glimpse of that future. A thought-provoking piece can inspire conversation or leave us with a feeling, just like a painting or a poem might. It helps us to flex our empathetic imagination.

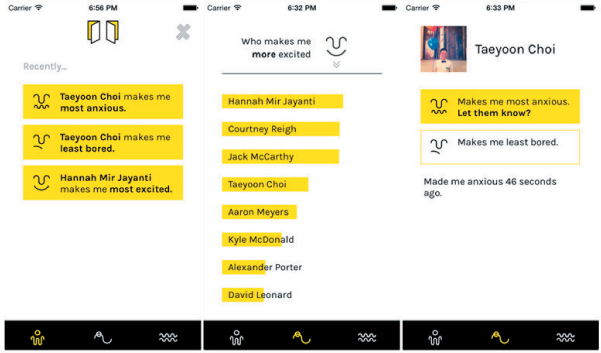

Some future objects even go further. Lauren McCarthy’s Pplkpr software gives us a glimpse of a future in which technology can read our emotional response to friends and family to gauge who is good for our emotional well-being. Pplkpr is not just presented as a concept in a compelling video, but it’s also available as an app to try out (Figure 6-11). So, you might learn, as I did, that your partner makes you the most angry and also the least angry, and that our communication doesn’t map one to one with our feeling in the moment. Living with the technology, even for a short time, is quite different from simply being exposed to an idea.

Figure 6-11. It’s one thing to view the future, and it’s another to actually try the future out (source: Pplkpr)

These future objects bridge past, present, and future through a simulation. The more we are encouraged to live with them and reflect on them, the better we’ll be able to feel the future. But there’s another way to create future artifacts. What if we could create a symbolic artifact that mediates our hopes and fears about the future? Rather than creating an artifact that simulates the future, it’s an artifact that is a metaphor for the future. Objects materialize our emotions, values, and beliefs, so it makes sense to model that, too. A kind of future-forward talisman.

Creative arts therapy highlights the human capacity to transform thoughts, emotions, and experiences into tangible shapes and forms. It’s most often part of an integrative approach, where art techniques like painting, poetry, and music are used in combination with other methods. In therapy sessions, people are encouraged to work through complexity creatively. Post-session, the objects can serve as a reminder or a way to prompt further thought.

In Chapter 3, we experimented with making emotion data into physical objects. Designer Lillian Tong at Matter–Mind Studio has been researching how we use objects as emotional tools in the present. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine creating an object that people could stand in for a possible future. For instance, what about an orb that symbolized a camera placed in a mailbox or above a door or in a kitchen to serve as a reflection point for facial recognition? Or, at one further level of abstraction, a collection of blocks that represented times of focus or relaxation that could be connected with time online?

The emotional force of the future can be explored by translating ideas into stories, or objects, or even meta-objects. Future artifacts can be more than a kind of Rorschach for the future, they can help us get better at recognizing, realizing, and regulating our emotions now and making emotionally intelligent choices about what’s next.

Future Thinking as Emotional Time Bending

“Imagining the future is a kind of nostalgia.” This is a line from John Green’s young-adult book Looking for Alaska (Dutton, 2005). It’s very popular on Tumblr. It’s also scientifically accurate.

Humans predict the future by using their memories. Often, when you remember, you are reliving the scene. You can hear conversations, you can smell lilacs, you can taste the madeleine. You feel those emotions anew. In turn, when you imagine an experience in the future you are preliving that scene. Once you become more skilled at it, you can cultivate sensory-rich, emotionally complex futures.

The time-bending properties of emotion can help us all get a little better at imagining (and making) better futures. Emotions tug at us, pulling us toward a future we think we might want. At the same time, the future is a kind of safe space where we can temporarily transcend our current worries and project our hopes. What better way to design with emotional intelligence than to follow our feelings toward the future?

1 Michael Dearing, “The Cognitive Distortions of Founders,” Medium, March 26, 2017.

2 Virginia Heffernan, Magic and Loss: The Internet as Art. Simon & Schuster, 2016 and Ellen Ullman, Life in Code: A Personal History of Technology, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Macmillan, 2017.

3 Martin E.P. Seligman, Peter Railton, Roy F. Baumeister, and Chandra Sripada, “Navigating into the Future or Driven by the Past,” Perspectives on Psychological Sciences, 2013.

4 Roy F. Baumeister and Kathleen D. Vohs, “The Science of Prospection,” Review of General Psychology, March 2016.

5 Jordi Quoidbach, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Timothy D. Wilson, “The End of History Illusion,” Science, January 4, 2013.

6 Hal E. Hershfield, Taya R. Cohen, and Leigh Thompson, “Short Horizons and Tempting Situations: Lack of Continuity to Our Future Selves Leads to Unethical Decision Making and Behavior,” Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes, March 2012.

7 The Institute for the Future, “The American Future Gap,” April 2017.

8 Jane McGonigal, “The Future of Imagination,” Aspen Ideas Institute, 2016.

9 Ting Zhang, “Rediscovering Our Mundane Moments Brings Us Pleasure,” Association for Psychological Science, September 2, 2014.

10 Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming, MIT Press, 2013.

11 Sara Watson, “Data Dada and the Internet of Paternalistic Things,” Medium, December 16, 2014.

12 Price Waterhouse Cooper, “Workforce of the Future: The Competing Forces Shaping 2030.”

13 Nicole Lazzaro, “Why We Play Games: Four Keys to More Emotion in Player Experiences,” 2004.