Chapter 7. Toward an Emotionally Intelligent Future

IT BEGAN INNOCENTLY ENOUGH. After enough Googling for “happiness and technology”—a practice that led me to uncover everything you would ever want to know about unhappiness and technology too—I began to see ads for the Thync: a plastic potato chip that sticks to your forehead, stimulating calm or energy, that seemed a sure way to automate happiness. I had to try it. Almost everything seems like it’s on demand, so why not emotional well-being?

Scientists have been working on how to stimulate the brain with electrodes for decades. Like so many of the cutting-edge technologies today, it began as assistive technology. Transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) is sometimes used to treat major depressive disorder (MDD). The military has been testing it to increase focus. An implantable chip, a real-life pleasure button for humans nicknamed the Orgasmatron, made headlines a couple years back.

Although the evidence that devices like Thync actually work is unclear, that doesn’t stop products from coming to market. And it certainly didn’t stop me from trying it.

In the relative calm of my office, I stuck the Thync to my forehead and dialed a medium setting (Figure 7-1). After a surprised yip from me and a curious head tilt from my Boston terrier, I had to dial it down to the lowest setting. After just a few minutes—much less than suggested—I had to remove it. I might have been looking for peaceful bliss, but instead I discovered a very highly concentrated headache. An intense wave of cyberchrondria (an escalation of health concerns based on internet searching) hit. I Googled Thync and long-term effects. What I found wasn’t terribly damning, but it wasn’t reassuring either. Despite the confidence that neuroscience seems to have in bokeh brain images, it seems like cracking the code of even the most basic feeling of pleasure in the brain is far from automation.

Figure 7-1. Can’t we just zap ourselves to happiness? (source: Thync)

This means that for the time being it’s up to us, as human beings co-evolving with technology and as makers of new ways of being, to take it on. The way we design our devices, websites, apps, and various internet things has a profound influence on our emotional well-being. If we want a human future for technology, we need to think seriously about our emotional life with our internet things and everything else.

By now, you know that designing emotionally intelligent tech is not just about soothing away difficult emotions with design conventions, or trying to make human emotion machine readable, or creating empathetic artificial friends, or zapping ourselves to feel more or less intensely. It’s a little bit of all of these things. But it’s much more than that, too. Fundamentally, it’s about taking the emotional layer of our experience with technology as seriously as the functional layer. And that has implications. In this final chapter, we look at the implications for the way we live and work.

Emotional Intelligence at Scale

Technology is perplexing when it comes to our feelings. You can get to your destination in a timely fashion and still feel disappointed, or carsick. You can hold a beautifully crafted iPhone in your hand and still feel depressed. You can engage with a well-designed website and still feel angry. A delightful detail can be staring you in the face, and you will remain unmoved (Figure 7-2). Tech designers, who have tried to create a spark of joy, know only too well how futile their efforts can be.

Figure 7-2. I could still be in a terrible mood, even after coffee and a reward (source: Starbucks)

It’s more than that, though. Our emotional life is changing. Each platform demands a different expression of ourselves, from email to text messages, social media, and video chat. As the new range of technologies detects emotion and adapts to it in various ways, we will adjust accordingly. At scale, this will change what we feel, how we express it, and how we relate to one another and our machines.

THE BRAVE NEW WORLD OF EMOTIONAL LIFE

Despite the best efforts of amateur and expert alike, emotions remain elusive. Better sensed than described; better depicted through art and film than analyzed as data; better lived than simulated. We don’t understand emotions unless we feel them, and then that experience becomes a blind spot. But if we look closely, we can begin to see that our emotional life is changing in a very real way.

In my own research, through a series of Future Feeling Labs held all over the world, some patterns emerge. I see the rise of six new types of feelings.

Micro—emotions atomized

Microaggressions, those brief and persistent messages that degrade individuals from marginalized groups, are not newly born of technology. But technology certainly enables them at scale. In the age of online shaming, we’ve all felt and maybe dealt small blows. Someone writes something unkind: bad enough. After thousands of likes and hundreds of mocking comments, you feel the giant force of the super small. Call it death by a thousand cuts or harmless torturing (a thought experiment once proposed by philosopher Derek Parfit years before social media), the micro can have an aggregate effect.

Other microemotions have yet to be identified. Think of the small compliments you might get throughout a day otherwise spent alone at home. There’s the almost imperceptible thrill you get waiting for a message from a chatbot (or am I alone on this one?). Then, there’s that feeling when you preface an everyday experience with TFW hoping for a little solace.

Microexpressions, thought to be a fleeting clue of inner conflict, will continue to receive more attention from the tech industry, for better and worse. Of course, humans detect microexpressions without being aware of it. Many people easily read slight changes in tone. Many more of us are starting to realize the slightest difference in tone or text can make or wreck someone else’s day.

Machines will become better and better at the smaller and smaller, perhaps revealing new truths about ourselves. They will certainly unearth nuances never before detected. You will likely never see 10 million faces, from all parts of the world, all ages, and all cultures and register their every minuscule change in expression. Facial coding datasets are already more extensive. You will never hear 10 million shifts in tone, or, if you do, you will not be aware of all of them. You only need to try out voice emotion AI to see how machines will easily become more skilled at tiny changes in inflection. At the same time, how we express emotion seems like it’s getting bigger.

Mega—emotional extremes

Since internet ancient times, humans have struggled to convey emotion on drab screens. In person, we can smile or twist our face in disgust, we can deliver a well-timed side-eye or quizzical gaze, we can wave away a concern or gesticulate wildly. Online, not so much. Instead, we’ve had a succession of stylized symbols: emoticons, emojis, animojis, gifs. The options keep coming but still somehow fail us. The conventions have changed over time, but confusion remains. Do you use :) or go with :-) old-school style? Do you choose LOL or a laughing face or the ha, ha reaction? ![]()

Conversational interfaces promise better communication but flatten out emotion, too. VR can transform the real into caricature. Whatever the new technology, the struggle is real. It’s still hella difficult to express emotion with machines in the mix.

So, we do what has to be done: we select all. One exclamation point used to suffice, but now we need three!!! We add lots of emojis in our texts, or only one. We exaggerate our facial expressions, squinching for our selfies as a counterpoint to blank stares at our phones. Soon, we’ll be sure to smile more often and more broadly so the machines can register it. Pair that with emotions breaking into bits and spreading through our networks, and you’ll see a new age of extremes. Longing, nostalgia, and regret are compressed into enough despair to require self-care. Rage rages through our social networks. Not irritation, or skepticism, or pique—rage. It ![]() is

is ![]() already

already ![]() happening.

happening.

Macro—emotional climate

You might have a good sense of the mood in your own home or at your office or even at a concert. You might also have a good sense of the emotional relationships, whether a reaction to a shared experience or an accumulation of everyday interactions. Humans are remarkable emotional climate sensors. But now we don’t need to rely only on our own read of the room.

Sentiment analysis in combination with geo-tagged social media posts, like the University of Vermont’s Hedonometer (Figure 7-3) or Humboldt University’s Hate Map, makes collective mood visible on a larger scale than we can imagine on our own. The latest emotion AI will go further, lending a more nuanced note to detecting and displaying emotion. The XOX wristband, worn by event-goers, registers and reveals crowd emotion at concerts and conferences, to build excitement or reinforce a communal feeling. On the flip side, it’s not difficult to see how it could just as easily divide the crowd.

Figure 7-3. The emotional climate of a nation (source: Hedonometer)

With new exposure to emotion at scale, emotional contagion takes on a new shape. Emotional contagion, in which your emotions trigger another’s emotion, happens on a small scale every day. We synchronize with the expressions and gestures of those around us. Neuroscientists study mirror neurons that embody this resonance. When it’s a positive, it’s usually called attunement. Contagion seems negative, even though that might not always be the case.

The network effect amplifies emotional contagion. Researchers at Facebook demonstrated this by skewing what roughly 700,000 people saw in their feeds.1 By tinkering with more positive or more negative posts, they were able to show just how easily emotion traveled from person to person. People shown negative status messages made more negative posts; people shown positives posted positive. Emotional contagion isn’t just face to face.

It turns out, certain feelings take precedent in this macro world of emotion. Just a few years ago, researchers thought that positive emotion, like curiosity and amazement, was the fuel behind viral content.2 That seems to be shifting toward the extremely negative, mostly outrage. Either way, high-arousal emotions like joy and fear and anger seem to travel with more speed and force—so much so that we are often highly aware of the emotions of others, especially certain emotions, whereas we miss many others that don’t travel quite so far, like sadness or loneliness or relief.

At the same time, we simply don’t register other network effects. In another recent experiment, psychologists showed people sad and happy faces in fast succession. Afterward, people were asked to drink a new type of beverage. People exposed to the happy faces rated the drink higher than those people shown the sad faces. The researchers interpreted this as evidence of unconscious emotion, or feelings we have without really even being aware.3

Macro emotions are never fully our own. Our awareness of the degree and impact of emotional climate is already changing with the aid of technology. Growing awareness of the emotional climate will likely prompt us to reflect on how we feel about feelings, too.

Meta—emotions about emotions

In everything from art appreciation to child rearing to romantic relationships, researchers have studied the feelings we have about other people’s feelings. You might tend toward dismissive, disapproving, or even overly permissive in your assessment of other’s feelings, but right now that judgment is usually reserved for those close to you. What happens when tech becomes involved?

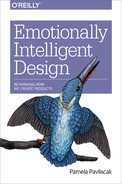

As we become more aware of the tiny moments, the rising tides, and the grand movements in emotion, meta-awareness is likely to be a part of our everyday life. Take a moment to review Lev Manovich’s experiment, Selfie City (Figure 7-4). In this collection of Instagram self-portraits from five cities across the world, you can see the range of expression across cultures. By using a slider, you can gain an understanding of how emotion takes shape, no doubt affecting your own affect.

Figure 7-4. Feelings about feelings that shape more feelings (source: Selfie City)

A big part of our life is a tacit comment on other people’s feelings. We might perform emotional work at work, out of consideration for others’ feeling or to influence them. Online we perform emotion, often in an exaggerated way to make sure that emotion is felt by others. As we become aware of technology detecting our emotion, we likely start performing emotion in a certain way for the machines in our lives, too.

As we are exposed to our own emotions in new ways, whether we see it as aggregate data to detect patterns or receive nudges based on how we are feeling, we’ll start to have feelings about that. Feelings that will, in turn, create new kinds of feelings.

Mixed—emotion reformulated

Awe, an emotion triggered by the vastness of the Grand Canyon or the beauty of Florence (in the days of the swoon, known as Stendahl syndrome), is a mix of emotions from inspiring to afraid to humble. Other emotions are culturally unique blends—for instance, saudade, that mix of nostalgia tinged with longing that is uniquely expressed in Portugeuse. But even those are changing. Consider schadenfreude, taking joy in other’s misfortune, shape-shifting in the form of an internet-specific pile-on.

All of these already-quite-complicated feelings are being stretched to capacity. As online and offline seep together, we keep extending our concepts of certain feelings. Maybe it’s that new addition to your annoyance repertoire that evolved from one too many humble brags, or the newfound infectious joy you experienced staying up all night to watch a raccoon make it to the top of a building with a band of fellow insomniacs. As the internet’s own unique culture intersects with global pop culture and amazing human diversity, feelings flourish in new ways.

Many more mixed emotions, yet to be uncovered, are unique to the new lives we are living. That undeniable urge you have to correct strangers online or that feeling when it seems like you’re the last person on earth to find out about something that happened minutes ago, are unnamed but widely felt and shared. The very spirit of the internet, after all, is in the remix—our emotional life included.

Machine—feelings by, for, and of technology

Researchers have long studied the emotional relationship between humans and machines. As noted in Chapter 4, it doesn’t take much for us to attribute emotion to machines and to attach to them. Companion robots are probably not going to replace human companionship; nevertheless, they will certainly be a part of many people’s lives in the near future (if not already). And they’ll take all kinds of forms: child-like droids to childlike simulations (Figure 7-5), disembodied therapy bots to rubbery sex bots, friendly giants to fluttery fairies. Some will be amazing, some will be awful, many we’ll love anyway.

Figure 7-5. Some of you will feel real love for this unreal baby (source: Soul Machines)

It can be a red herring to debate whether they will “have” emotions, because we don’t really know what that means anyway. David Levy argues in Love and Sex with Robots (HarperCollins, 2007) that if a robot behaves as though it has feelings, it can be difficult to argue that it doesn’t. With devices exposed to human emotion on a scale more extensive than many of us experience in a lifetime, bots will certainly have some kind of emotional intelligence, though. More than that, just as certain breeds of animal have coevolved with humans to understand our emotions and express emotion so that we feel that they have emotions like ours, bots will likely move toward that, too.

Annette Zimmermann, vice president of research at Gartner, said, “By 2022, your personal device will know more about your emotional state than your own family.” Gasp if you must, but that might already be the case. You probably wouldn’t hand over your phone even to someone close to you, much less a mere acquaintance. Whether you believe that our devices will know more about us than our family members, they will certainly begin to know not just what we do but how we feel.

For now, the worry is that technology is taking too much of a toll on emotional intelligence. People are less self-aware as emotions are exaggerated online. Empathy might seem diminished in the wake of more screen time. Impulse control becomes more difficult in an era of attention-grabbing. So far, that’s more correlation than causation. And it’s not the entire story. For each of these negative takes, there are also positives. As our emotions atomize or crescendo or radicalize, we’ll relearn emotional intelligence, too.

Technology will reshape our consciousness in ways that won’t be evident for years to come. The new tech-infused emotional intelligence will reshape not only our private lives but our public lives as well.

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AND PUBLIC POLICY

In the 21st century, emotional health is a key goal of public policy, championed by psychologists, economists, charities, and governments. Those lucky enough to enjoy emotional well-being are less likely to suffer from a range of mental and physical disorders, such as depression, addiction, anxiety, anorexia, irritable bowel syndrome, or heart disease.

Scientists, doctors, philosophers, and politicians now talk about emotions such as anger, worry, fear, and happiness as causes or symptoms. But what is the perfect recipe for emotional health? Who decides which emotions we should feel, and when?

In the past few decades, the emotion driving policy has been loosely defined as happiness. Smart Dubai, for instance, use sensors and analytics to promote happiness (Figure 7-6). By tracking what people do and how they behave in combination with online sentiment, they aim to cultivate happier citizens. The citywide Happiness Meter makes happiness transparent to policy makers, affecting spending on transportation, health, and education. Smart Dubai is an ambitious initiative, but it’s not only one. From the Bhutan Gross National Happiness Index to Santa Monica Well-Being to the World Economic Foundation sustainable development goals, happiness is an emotion that drives policy big and small.

Figure 7-6. Citizen happiness already shapes public policy (source: Smart Dubai)

Whereas happiness is an explicit emotional goal, there are others that drive public policy without formal adoption. Legal institutions, charged with regulating individual emotion and responding to public sentiment, are shaped by anger and remorse. Outrage, simultaneously tracked and fueled by technology, is driving political action all over the world. Empathy, whether through real-life or VR-based refugee experience simulations, assists policy makers to assess impact as well as influence public support. For example, MIT’s Deep Empathy initiative simulates how cities around the world would be transformed by conflict using deep learning. Emblematic Group walks people through devastated Syrian cities (Figure 7-7).

As cities begin to profile more data through cameras, sensors, and biometrics, the emotional experience of public life will become even more evident. The opportunity to improve the design of cities and to raise the well-being of all citizens is real. In the near future, designers will be tasked directly with using this data to create environments that support emotional well-being.

Figure 7-7. Virtual witnessing potentially influences policy (source: Emblematic Group)

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE IN THE ORGANIZATION

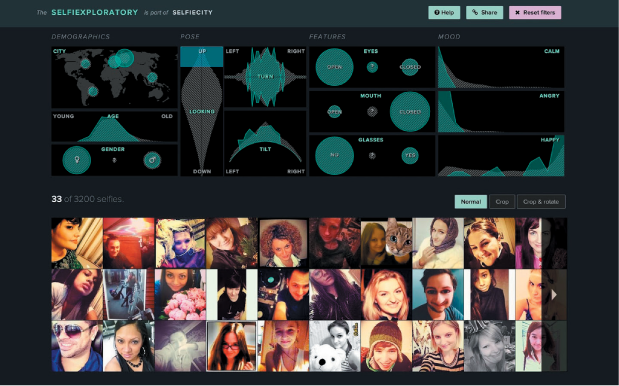

Emotional intelligence, at scale, is not just changing our personal lives but is becoming foundational to organizational culture. I challenge you to go a day without coming across a headline in Harvard Business Review, Forbes, or Inc. about the importance of emotional intelligence in the workplace. The World Economic Forum, in its report “The Future of Jobs,” ranked socio-emotional skills as increasingly critical for future careers. Business schools are adjusting their curricula to include emotional intelligence. Companies like Google offer emotional intelligence courses. Organizations like the School of Life or Brain Pickings are on a mission to bring emotional intelligence to the masses. Tools to measure EQ or track employee happiness (Figure 7-8) are near-ubiquitous.

Figure 7-8. How do you like me now? (Source: TinyPulse)

Although organizations seem to value the emotional intelligence of leaders and the emotional well-being of employees, emotional labor itself is undervalued. Customer service agents, caretakers for the young and the elderly, and social workers are not paid well relative to other professions. The concept of emotional labor isn’t new. Arlie Hochschild first published The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Emotion (University of California Press) in 1983. But the mental health issues associated with emotional labor are more relevant than ever.

It looks like this is an area where emotion AI is ready to assist. AI to augment the emotional intelligence of human customer service reps is already in use. Japan is leading the charge to develop emotionally intelligent AI to care for the elderly, from robot therapy pets (Figure 7-9) to home health chatbots. Perhaps the required relentless cheer of Disney employees and Walmart greeters will be next for an emotion AI upgrade.

Figure 7-9. Where humans won’t go, robot seals dare tread (source: PARO)

Whether it’s leadership or team building or individual success, creativity or collaboration, organizations have already embraced emotional intelligence for humans. Emotional labor is beginning to get its due, with emotion AI potentially supplementing roles or even providing relief. What will it take for emotional intelligence to become a part of product design in the organization?

The market for emotion AI is estimated to grow exponentially. It’s easy to see why. Companies will want to get a competitive advantage by learning more about what people feel. For tech companies relying on personal data, it’s a wide-open world of customer insight. And it’s easy to imagine how that could veer toward manipulation, especially given the trend toward optimizing for transactional emotion.

All of the tech giants have tried to crack the psychological code for emotion, however indirectly. So far, the tech industry optimizes around key metrics that favors some aspects of emotion. In-the-moment behaviors like time spent or scroll depth or number of clicks stand in for in-the-moment engagement or even delight. For Amazon, it might be evident in product recommendations. For Facebook, it’s determining which posts show up in the feed. For Candy Crush Saga, it’s knowing what to offer for free or not. Optimizing for short-term emotional gains is still the primary mode of operation for tech companies, and it often comes at the expense of emotional sustainability.

Moving forward, products and services that are more emotion-aware will provide real value. Market positioning is one factor. If given a choice (and in certain sectors that is less and less the case), frictionless can translate to blandly predictable. Think already of the experience of planning travel, where a typical journey consists of 20-odd sites that are quite disposable after booking. Think of the speed at which people try to “get through” certain experiences, often not just out of time-saving or convenience.

Easy and efficient, those pillars of user experience are still relevant, of course. You probably appreciate the ease of tracking travel expenses or making a remote deposit at your bank. But easy and efficient are often synonymous with expendable and interchangeable. An emotionally satisfying experience is one that stays with you.

People are becoming increasingly aware of how some apps make them feel distracted or even creeped out. More and more, people are beginning to wonder about the emotional toll. People are actively looking for products that support emotional well-being in all kinds of ways, from fitness to mental health to mindfulness. Emotionally intelligent products will become a key selling point.

With the advent of emotional AI, expectations will shift to demand more of technology, beyond ease and efficiency. Rana el Kaliouby, CEO of Affectiva, says that “10 years down the line, we won’t remember what it was like when we couldn’t just frown at our device, and our device would say, ‘Oh, you didn’t like that, did you?’”4 Products that acknowledge emotion and enhance well-being without breaking trust will stand out.

Attracting talent will drive further organizational change. The talent marketplace has never been so competitive. A company offering an emotionally intelligent product or service will attract and retain talent, particularly among designers and developers who have a strong impulse to change the world for the better. And by showing that the company values its relationship with its customers, by extension, it means that it’s likely to value the relationship with employees.

Whether organizations slowly adopt new measures or radically shift values or try to continue along their current path, change will happen anyway. Metrics like page views and retweets and likes will inevitably fade. Persuasive tactics that work now will be exposed and become less effective. These measures will have to be replaced by something. Future-forward companies will start to think differently about creating a relationship with customers by doing some of the following:

Consider the emotional layer of experience, not just the functional layer.

Measure on multiple factors, including emotion and other aspects of subjective well-being.

Develop for long-term goals that offer emotional support, personal growth, and social connection.

Frame value to a broader range of stakeholders, not only shareholders and business partners.

Make emotional factors legible so that the relationship is meaningful and respectful.

The value of a long-term relationship aligns with growth. If we look at what people choose, when given a real choice, it’s often emotional. If we look at what makes people stay, it’s an emotional investment. If we look at what contributes to a good life, it’s technology that supports emotional well-being.

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE AND ETHICS

Designers struggle with the unintended consequences of the products they create, from spreading hate speech to exacerbating mental health problems. Beyond “do no harm” or “don’t be evil,” conversations about ethics in tech are often framed around personal autonomy. But I wonder if this isn’t another area in which we should let emotional intelligence guide us. Where there are strong or conflicted feelings, you are sure to find the most pressing ethical conundrums.

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum, in Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions (Cambridge University Press, 2001), argues that emotions are central to any substantive theory of ethics. The most important truths about humans are not grasped by intellectually activity alone, but by emotion. Emotions expose our values. Grief, for example, presupposes the belief that whatever has been lost has tremendous value. So, if you believe someone is important in your life and that person dies, you will experience grief. This extends to bigger issues of identity, too. If someone says they are a feminist but witnesses an act of abuse without reacting, people might question the sincerity of those convictions, for example.

Anger seems like one possible emotional starting point for tech ethics. If there’s any one emotion that characterizes the internet, it’s anger. We’ve evolved from flame wars to fake news. We inexplicably feel the urge to argue with strangers on the internet. Since we disassociate a bit when we’re online, we might express our rage more virulently. Moral outrage prompts comments and sharing. That rage multiplies. After we log off (or whatever, you know what I mean), we might feel a kind of anger hangover for a while or a longer-lasting rage flu. Anger shows what we value, certainly. But it takes on its own life. And it’s rewarded by attention, human and machine. What if we started with anger and, instead of letting it spread or fester (or profiting from it), we looked at ways to encourage the hard work of self-examination or civic engagement? The more we understand the emotional undercurrent of experience, the more emotions can become an ethical compass, guiding us toward what we value.

Human emotion has been proposed as the antidote for a future where artificial intelligence takes over so many of the things we do now. Quite honestly, we are not all experts at emotional intelligence just because we are human, either. We have trouble recognizing our own emotions, we often don’t respect the basic humanity of other people, we discount emotion or go to great lengths to avoid it. So, while I’d like to remain hopeful that the dawn of AI will lead humans to develop even greater compassion, lead us to value emotional labor highly, and teach emotional intelligence, it’s not quite so simple. The idea of the human as the emotional layer of the operating system has its own limitations to overcome. But one thing is clear—we need emotionally intelligent humans to develop emotionally intelligent technology.

A New Hope for Empathetic Technology

An emotionally empty future of sleek glass houses and glossy white robot servants speaking in soothing feminine voices is not my ideal vision of the future. I bristle at seeing ambitious future museum projects divorced from everyday realities. Donut-shaped tech campuses designed for living full-time at work don’t seem like an emotionally satisfying way forward. Living forever doesn’t much appeal to me (from an emotional well-being perspective, it’s fraught, too), and I wouldn’t be likely to afford it anyway.

The future we are living toward is quite a bit messier. If you look at your day-to-day life, you’ll uncover how much of the internet and all its related technologies have a hold not just on your home but also on your experience of nature, your social life, and your psyche. You’ll also realize that you are still using all kinds of technologies from previous eras, no matter how thoroughly modern you try to live. We aren’t going back, but we will have to live with the mess of the past too.

Maybe there is a hint at the future in the undercurrent of how people already use the internet. We design devices, apps, websites, and internet things for speed, efficiency, and productivity, yet another set of values lies just below that clean veneer. The handmade, authentic, vulnerable, amateur, stupidly funny, tragicomic, flawed—these are the values of internet culture such as it is. Those values have persisted since the dancing hamsters of Web 1.0. They persist despite the corporatization of the internet. You’ll find them in how people engage with technology every day.

Lately, people have asked me how it’s possible to be hopeful given the pileup of negatives—fake news, AI gone wrong, a widening technology divide, net neutrality under threat, the creepiness of emotional surveillance, and well, *gestures broadly at everything* all of it. One minute you’re “techsplaining” how it will all be okay, and the next you’re seriously considering opening up a bakery. And isn’t it selfish to think of something as frivolous as feelings when there is so much at stake? How can you write a book about emotions when the world is spinning out of control?

Despair is not an emotion that propels us into the future. It tells us that nothing we do matters, issues are too complex, and one person can’t make a difference. It ensures that those benefiting from the continuation of the problem are safe. It breeds apathy. Cynicism might look like rebellion, but it’s not. It’s status quo. So perhaps we should consider another emotion—hope.

Hope, in contrast to despair, can be revolutionary. Hope is optimism that is deeply thoughtful and fully engaged. Hope is lucidly mobilizing. Hope is a belief that meaningful change is possible. Hope is choosing to contribute to a positive future.

Rather than neatly tying up loose ends, together we can encourage people to tell their own stories. Rather than looking toward a utilitarian logic that rewards the most efficient, together we can redefine success. Rather than optimizing for convenience, we can make room for a messy, emotional meaning surplus. Together, we can craft bolder visions, tell better stories, and embody them persistently to support a different idea about the future.

Let’s start.

1 Adam D. I. Kramer, Jamie E. Guillory, and Jeffrey T. Hancock, “Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion Through Social Networks,” PNAS, June 17, 2014.

2 Kelsey Libert and Kristin Tynski, “The Emotions That Make Marketing Campaigns Go Viral,” Harvard Business Review, October 24, 2013.

3 Jim Davies, “You Can Have Emotions You Don’t Feel,” Nautilus, March 9, 2018.

4 Raffi Khatchadourian, “We Know How You Feel,” New York Times, January 19, 2015.