Chapter 5. Crafting Emotional Interventions

LIKE MANY PEOPLE WHO live in colder climates, I struggle with seasonal affective disorder. Having blown through some of the typical advice, like special lighting and fresh air, I was looking for something new. That’s when I came across Koko, a crowdsourced approach to emotional well-being (Figure 5-1). Koko asks you to choose a topic of concern, like work or school or family, and to write your worries about a worst-case outcome. When you click “Help rethink this,” your request goes out to a community. Community members—some trained in cognitive behavioral therapy techniques, some not—swipe through each card to see if they can help. It offers a few prompts like, “A more balanced take on this would be…,” or, “This could turn out better than you think because…,” for those who want to help. Comments are moderated in real time and an algorithm watches out for trigger words that can signal a need for a more serious intervention.

Accepting rethinks helped steer me away from dark thoughts. After a while, I began offering some advice when I felt I could. The app not only helped me build resilience by rethinking stressful situations as a helper, but offered a sense of empathetic community, too.

Koko is only one of many sleep trackers, therapist bots, anxiety coaches, and mood monitoring apps that help us pursue emotional well-being explicitly. Technology as a mental health intervention is becoming accepted practice. That makes sense because we know there’s a lot we can do when it comes to designing our own happiness.

Figure 5-1. Crowdsourced interventions create an empathy buffer (source: Koko)

Happiness is not all genetics, not even by half. There are about a million things you can do to be happier, but most of us don’t do any of them. In The How of Happiness (Penguin, 2007), Sonja Lyubormirsky calls these intentional activities interventions: “In a nutshell, the fountain of happiness can be found in how you behave, what you think, and what goals you set every day of your life.” Interventions can be a big dramatic break. More often, interventions are more like small changes that reframe our attitudes or actions. Activities that can shake us up a little so that we can feel a little bit happier every day.

In this chapter, we take a cue from the idea of interventions. In psychology, the concept spans cognitive mediations to behavioral nudges. Interventions are used in healthcare to prevent bad health-related behaviors and promote good ones. Interventions to prompt a psychological or social shift are already in wide use in architecture and urban design, too. Let’s first look at how many of us try to craft our own interventions when it comes to tech use.

Strategies for Living Digital

Think about your day so far. <pause> I’ll share mine. Maybe it will sound familiar. It’s still early in the day. I’ve refreshed my Twitter feed more times than I can count, ultimately leading me to a review for a book I’d like to read, then over to Amazon to purchase that book, then to Goodreads to note that I started it. It helps me keep track, but someone might be interested. I briefly entertain a fantasy about the fascinating discussion we might have, inserting various people I know into the slot of potential readers.

Rather than diving in to reading the book right now—I have to get to writing, after all—I decide to get in touch with several friends from grad school to remind them of this author’s first book, which we had discussed on Facebook at one point. It’s been a while and I wonder what’s happened to a former professor from those years. A quick Google stalking session later and I can breathe a sigh of relief—still alive! After checking email, naturally, I go upstairs and find the actual print copy on my bookshelf and set it on my desk. Time for a snack. I’m eager to try that smoothie I saw in my feed (ha!) and then I’ll really be able to settle in for work.

Even as tech makers and internet evangelists, we feel conflicted. Is our time wasted or productive? Is technology addictive or creative? It feels like it can be both, but how to find the right balance? Perhaps we can learn from the strategies people use every day.

RULES AND TOOLS

Recently, I asked almost a thousand people to share their mantras or personal guidelines for using technology. They shared some internet truisms like “Don’t read the bottom half of the internet” and some more forward-thinking ideas like “You shouldn’t have to talk like a robot to talk to a robot” (which inspired the “speaking to a bot” experiment discussed in Chapter 2). By far, most of the mantras were about finding balance, like “One hour offline for every hour online.” Anya Kamenetz, in her book The Art of Screen Time: How Your Family Can Balance Digital Media and Real Life (Public Affairs, 2018) sums it up neatly: “Enjoy screens. Not too much. Mostly with others.”

People use a combination of rules and tools to live up to their personal guidelines. Apps that monitor time online or limit time on certain apps act as personal interventions. Plug-ins like OneTab that convert your tabs into a list, or simply choosing not to restore tabs when your browser crashes, is a sort of self-care. Low-tech rules for screen-free meals or detox weekends are even more common.

Beyond aspirational guidelines, we’ve developed coping mechanisms, too. We’ve had to. People are using Facebook to showcase suicides, beatings, and murder in real time. Twitter is rife with trolling and abuse. Fake news, whether created for ideology or profit, runs rampant. The internet loves extremes. A clickbait headline, a provocative post, a half-exposed image. People look, the algorithms are trained, and so the internet supplies more of that. To counter all these very real and negative feelings, we have emojis, memes, irony, and dark humor. And we duck for cover under anonymity and fake identities—so much so that there are more 18-year-old men on Facebook than there currently are on earth.

Certainly, people also push the limits of technology to make their own happiness. Witness the sublime creativity of Amazon reviews for Tuscan milk and Bic Pen for Her and horse masks (Figure 5-2). People will always subvert designed spaces, from street art to ASCII art. They will empty their cache to see if they get another 10 days free, set up real accounts to be fake and fake accounts to be real, and try any manner of workaround available. That’s being human on the internet.

Figure 5-2. The lighter side of coping strategies (source: Amazon)

Sometimes we engage in a little magical thinking. Think about athletes’ pregame routines or the elaborate sleep rituals weary parents try out for cranky babies. More often, magical thinking is an irrational response to gain a moment of control. In the context of technology, we see this in the ways that people try to game algorithms to adapt them. People might try to like a certain type of post, or delete old posts, create more posts, unfollow and refollow in an attempt to change what they see. When it doesn’t work as expected, it can lead to feelings of futility.

Personal guidelines and finely tuned coping strategies get us only so far, though. It’s fine to put responsibility on ourselves for how we choose to live with technology. But obviously, design should take some of the responsibility, too. Technology demands our attention in ways we don’t always anticipate or intend. It requires emotional labor educating, placating, soothing people we know well and people we don’t know at all. And it shapes our experience in ways we don’t fully understand, so much so that we develop our own folk theories about how it all works, whether inside or outside the industry.

Individuals design interventions by setting ground rules for behavior or relying on coping strategies to get us through each day online. Interventions can also take place on a larger scale. Nudges are one of the ways sociologists, politicians, and economists have already tried.

JUST A LITTLE NUDGE

We slip up all the time. We eat the donut, we forget to take our medication, we don’t save for retirement. Technology doesn’t always help in that regard. Automated payments let us buy things a little too easily, games encourage kids to spend real money on virtual things friction-free, autoplay sets binge watching in motion. Until recently, most phones didn’t even offer a driving mode to prevent us from killing ourselves by texting in our cars.

Nudges, a construct from behavioral economics, guide behavior toward better choices. A nudge, according to Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, is “any aspect of a choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.”1 The ideal nudge guides people to positive choices without eliminating choice altogether.

Better defaults, such as retirement accounts that minimize the effort toward participating and contributing, can help. Motivators that take advantage of social norms such as reciprocity, relatedness, or coherence are another common type of nudge. Badges, metrics, and motivational messages, like the Nest Leaf (Figure 5-3), reinforce positive behaviors without making you feel too bad when you slip up.

Figure 5-3. Wasted energy gathers no leaves (source: Nest)

Even so, nudges are tricky to employ. Nudges should be for the good of the individual rather than the good of the “choice architect,” but with the pressure of super-fast growth, that balance is difficult to achieve. Nudges can be distasteful, such a highlighting an option for travel insurance that is nearly impossible to collect. Or they can be disastrous, like the mortgage industry encouraging people to take out loans they couldn’t afford. Designers and developers find themselves caught between nudging for the good of the individual and nudging toward business goals all the time. Often, those two directions are at odds.

Other complications abound. The good of the individual is always situated in a larger context of the good of society, and not all nudges are good for both. Then factor in the biases and quirks of the nudgers themselves. Who gets to decide what is a positive outcome? And how do we gather evidence that the outcome was indeed positive? And for whom? And, of course, we are famously bad at predicting outcomes. And outcomes are difficult to predict because systems are dynamic.

Well, that escalated quickly. But if we can set all that aside, perhaps there is something worthwhile. In truth, we must base our decisions on something, and those decisions will have an impact on well-being. Whether we actively create a nudge or not, stimuli are embedded in our environments already. If you look around, you’ll not see much that hasn’t been designed. Any designed object provides a script; we can avoid it or improvise, but the impact is real.

A nudge is one kind of behavior change intervention, often compensating for a deficit by relying on a deficit (usually, a cognitive bias). Interventions don’t just guide us away from negatives, though. They can move us toward positives, too.

EMOTIONAL WELL-BEING INTERVENTIONS

Self-help books are full of ideas about what people can do to become happier, ranging from practical to cringe-worthy. It’s only relatively recently that research has developed strategies with science behind them.

Psychology professor Sonja Lyubomirsky proposes 12 intentional activities, validated through extensive testing, to support well-being. These activities include expressing gratitude, cultivating optimism, avoiding social comparison, forgiving, savoring, and experiencing a flow state more often, among others.

Following this lead, the New Economics Foundation proposed five evidence-backed ways to support personal well-being: connect, be active, take notice, keep learning, and give. Likewise, mental health and emotional well-being apps like Happify apply interventions to boost well-being. Happify’s STAGE model—Savor, Thank, Aspire, Give, and Empathize—supports activities in each of these core categories. These models aren’t just created in a vacuum. Happify’s model, for example, is backed by an exhaustive collection of research for each of the principles.

Interest in the idea of interventions is not limited to personal well-being, however. The design world has begun to create interventions as a way to amplify positive experiences. Sustainability consulting firm Terrapin Bright Green recently introduced patterns of biophilic design. The relationship between the built environment and nature can be developed to reduce stress and cultivate community. Knowing this, the firm identified patterns that can support the well-being, ranging from visual connection with nature to spaces that support refuge or inspire a sense of mystery.

Happy City, Charles Montgomery’s consulting firm, uses lessons from psychology and public health to design happier cities. Dense, mixed-use, walkable spaces build trust and reinforce a sense of community. Apartment buildings with convivial common spaces, rather than computer rooms, build friendships. Building on these patterns, the firm’s work takes the form of interventions, like pop-ups around a warm cup of cocoa to build neighborhood bonds, or one-day events to transform parking lots into green spaces or intersections into piazzas.

The Delft Institute of Positive Design, led by Anna Pohlmeyer and Pieter Desmet, features a long list of positive design interventions, from designing for mood regulation to savoring experience. In their book Positive Computing: Technology for Well-Being and Human Potential (MIT Press, 2014), Dorian Peters and Rafael Calvo suggest the idea of design interventions to support motivation, self-awareness, mindfulness, resilience, gratitude, empathy, compassion, and altruism.

Positive interventions make us happier in all kinds of ways—injecting creativity by stimulating the senses, enhancing agency over our environment, or prompting more meaningful social interactions. Whether clear prompts or subtle patterns, these interventions can be designed.

Interventions with EQ

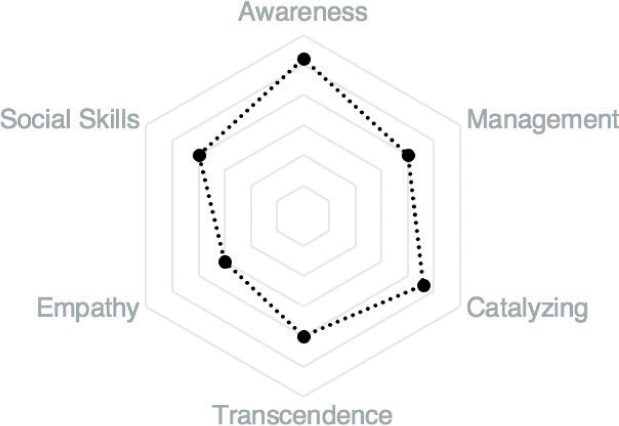

Inspired by what I’ve observed in diaries, design dinner parties, and data, and illustrated with examples from my research, I’ve assembled interventions that roughly follow the tenets of emotional intelligence.

Self-awareness (appreciation, self-compassion)

Self-management (focus, flow, resilience)

Self-catalyzing (motivation, creativity, hope)

Social skills (generosity, gratitude, forgiveness)

Self-transcendence (wonder, compassion)

I’m cheating a bit by bundling together vital activities for the sake of brevity. This is not an exhaustive list. Many of the patterns overlap, because what is conducive to focus turns out to be critical to appreciation, or what is foundational to generosity evolves out of empathy. And not all of these activities are relevant to every experience.

So, what you’ll find here is a mix. Be aware of the negatives and stop exploiting them. Employ nudges to compensate with caution. And use positive interventions to help people flourish.

Self-Awareness Interventions

Most of the time we’re busy. We try to multitask. We aim to get things done. That means we aren’t paying enough attention to the good things. The simple act of identifying something good and then appreciating it fills us with optimism, dampens our desires for more, and deepens our relationships with loved ones.2 When we express our gratitude to someone, we get kindness and gratitude in return.

The internet is basically the opposite of “stop and smell the roses,” though. Recency and speed are valued above all else—in how we interact and how we develop experiences. For instance, today’s meme is listing 10 bands and then having your friends guess which one you haven’t seen. Rather nice in that it strengthens relationships through appreciating a moment, often spent together. Too bad we will have long forgotten it by the time this book makes it to print.

It’s not just the cult of the most recent, of course. The ephemeral quality of digital life works against appreciation. When was the last time you clicked through all the photos on your phone? The sheer number can make reviewing seem an insurmountable task. Many are not worth remembering in the first place (or maybe that’s just me). Then there’s social media feeds and news apps and the trail of abandoned technologies we leave behind.

Yet, the ability to appreciate in all its forms—savoring the moment, engaging in rosy retrospection, and anticipating the future—is at the heart of happiness. Building emotional awareness through reflection prompts us to craft stories, make meaning, and form connections. Let’s look at some design interventions to stimulate appreciation.

POSITIVE SELF-AWARENESS PATTERNS

Right now, design pays a lot of attention to in-the-moment experience. If we are thinking about emotion at all, it’s likely to be how frustrated or happy people feel when they’re directly engaged with the product or service. Interventions that spark appreciation would help us to savor a moment or expand its significance but also call up a memory or anticipate an event. Following are a few patterns to support positive self-awareness:

- Memory prompts

- Emotional memories build resilience. Regular immersion in our memories is a critical part of what can sustain and console us. We’re always trying to make future decisions in the hope that it will make us happy, but your past has guaranteed points of happiness. Apps like TimeHop or Facebook’s Memories attempt to prompt reminiscence. These apps work well as a way to turn remembering into a scalable, consumable, trackable product, but not so well for actual reminiscence. And, of course, they can go horribly wrong by reminding us of things we’d rather forget or just posts that weren’t meant for remembering. The kernel of the idea, though, has potential, perhaps with more ways to control the prompts.

- Digital–physical bridges

- Bridging digital and physical cultivates awareness of both. Pokémon GO certainly seems to fit this pattern, not just by hiding objects to find, but by creating moments to discover new places and new people. Traces is another good example of a bridge. Traces is part messenger, part surprise-gifting service that lets people leave digital messages at physical locations for their friends to pick up with their smartphones.

- Sensory burst

- Activating the senses heightens awareness. The more stimuli we have to process, the more we pay attention. The new sights, sounds, and smells of a rich experience encourage us to savor. Experiences that engage the senses, especially in a world of screens, might encourage appreciation. Project Nourished’s virtual reality (VR) dining experience, which combines a VR headset, aromatic diffuser, gyroscopic utensil, and 3D-printed food is an over-the-top example (Figure 5-4). Everyday sensory examples are games like Tinybop’s Plants or TocaBoca’s Toca Lab.

Figure 5-4. Virtual eating, real sense activation (source: Project Nourished)

- Reflection points

- Pauses that encourage us to take a moment to think, feel, or celebrate. We can probably think of silly examples of celebrating because it’s a typical example of delight, like the burst of confetti when we finish a module on the Happify app. But it can be more than a quick burst: it can be a moment to reflect, too. For a time, LinkedIn’s mobile app designed a way to review just a few status updates at a time and then build in a pause. Nike+ Run Club prompts runners to reflect on their run with pictures and notes. Even slowing down to take a picture of your food on Instagram has been found to help people enjoy their meal more.3 Perhaps in the future, we should be prompted to pause more often.

- Happy trails

- Anticipating a happy endpoint builds appreciation. Endings are rare in our experience of tech. Back in 2014, when I was really starting in earnest to test new ways of understanding experience, one activity I tried was to have people draw what they remembered of a favorite website or app. You would think it would be easy to roughly sketch something you use all the time. But people didn’t remember that much besides buttons and checkboxes. And most people drew the beginning of the experience. Hundreds of times over, even with different prompts, like “draw what you remember” or “draw what’s most important,” I got app icons and home pages, as illustrated in Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5. All beginnings and no endings

We are missing endings, and that’s a shame when it comes to appreciation. We are more apt to remember endings. The snapshot model of memory, developed by Barbara Frederickson and Daniel Kahneman, tells us that people judge the entirety of an experience by prototypical moments, privileging the peak and the end. Often there isn’t a marked ending to many tech experiences, but when there is an ending it’s often a low. Paying for a purchase, rating a driver, and even being asked to share are closure experiences, benefit of the business more than an individual or a community. How else can we try to create happy endings?

Surprises such as a discount code or a donation, especially when they aren’t contingent on a share or a like, can create a positive last impression. Even when we simply imagine something coming to an end, we are better able to appreciate it, too. IKEA Place, the augmented reality app that helps you to place the furniture in a room and build it, builds positive anticipation of a projected ending. Thinking more broadly about endings might help us when it comes to appreciation.

Because many of our experiences don’t have clear endings, we instead can reinforce happy associations. For example, Intercontinental Hotels Group launched an iPad app that gives guests the chance to re-create their favorite meals. Booking.com shows you your next potential destination, so that if you are spending two days in Lisbon, Porto might be your next destination. Maybe beginnings are the new endings.

SELF-AWARENESS ANTIPATTERNS

Positive interventions help us to develop a new appreciation for both the novel and the mundane, which can cultivate self-awareness. On the flip side, experiences that cycle us through the same experience, again and again, numb us to appreciation. Here are some examples:

- Ludic loops

- An action linked with an intermittent, variable reward leads to thoughtless repetition. The ludic loop lulls you into a state in which you are perfectly content to do the same thing over and over again. Anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll, in her book Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Vegas (Princeton University Press, 2012), first identified this pattern when studying how people become entranced by slot machines in Las Vegas. Pulling to refresh your Twitter feed, swiping on Tinder to see whether you got a match, and obsessively opening up Instagram to see if you got more likes are all examples of interactions that work on the same principle as a slot machine. Cycling through apps, moving repetitively from Twitter to Medium to email, would certainly qualify too.

- Metrification

- Reducing all the key parts of the experience to numbers feels mechanical. There’s no question that counting steps or tracking sleep can have health benefits. At the same time, it can encourage us to be perpetually dissatisfied. In his book, Irresistible: The Rise of Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked (Penguin, 2017), Adam Alter calls this metrification. We aim to beat our last goal. We head outside for another quick walk to make our quota for the day. We constantly crave more followers or likes. We compete with ourselves and with everybody else. It’s a game that’s impossible to win. It can motivate, but it can also mechanize.

Successful self-awareness interventions slow down time to let us reflect on ourselves and enjoy the good qualities of life. Sensory engagement, mixed emotion, and novel experience help get us to that place. But being aware of yourself and your experiences is only one aspect of emotional intelligence. After we’re aware, we need to find ways to regulate emotional life.

Self-Management Interventions

Our attention is a scarce resource, and yet every app, every website, every device demands its share. Our experience of technology is about much more than time, it’s about creativity and adaptability and meaning making. Even so, we should look at how we spend attention. The ability to focus is closely tied to emotional well-being. From Linda Stone’s work on task switching, to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of flow to Cal Newport’s writing on deep work, a similar principle holds true. This might explain the recent interest in mindfulness and how it relates to technology use.

Mindfulness, or the practice of present-moment focus and awareness, has been linked to reducing stress, enjoying greater life satisfaction, and making wiser decisions. Mind wandering can detract from happiness—there is research aplenty on that, most notably by Matthew Killingsworth.4 The idea behind modern mindfulness training is that we can decrease stress and increase well-being by changing our relationship to an experience.

Mindfulness is often touted as the antidote to technology overuse. There is no shortage of books devoted to applying mindfulness to technology, whether using technology to become more mindful or using it in a mindful way. From Wisdom 2.0 conferences to focus apps like Forest (Figure 5-6) to digital detoxes, the idea of being more mindful of our use of technology is starting to take hold. What if we could factor some of that thinking into the creation of technology?

Figure 5-6. Focus or the tree dies  (source: Forest)

(source: Forest)

POSITIVE SELF-MANAGEMENT PATTERNS

Interaction Design 101 says that good design removes friction. We smooth out the rough edges of experience so that there is little possibility of failure. Smart products learn about us, recognizing patterns in our behaviors to anticipate our next move. The goal is to save time and effort.

Frictionless design can be overwhelming, though. As designers, we need to pay attention to this yearning for mental whitespace. Just as design whitespace gives us the space to focus while looking at printed page, mental whitespace encourages us to pay attention to our own thoughts and feelings. Only with the space to reflect and synthesize can we get creative and make ideas our own. A few patterns follow:

- Optimal stops

- Endpoints that are inserted into a process can get us back on track. We don’t have time to process our experience. As a counterpoint, some experiences are building in pauses. For instance, Etsy tested infinite scroll and found it left people feeling lost. People needed a boundary to mentally sort through results. Medium doesn’t rely on a feed; there’s a finite number of posts on the landing page. The Quartz mobile app reveals a finite number of stories per day (Figure 5-7) and lets people choose how much detail they want for each story, allowing individuals to pace themselves.

Figure 5-7. Go in-depth or just get the gist (source: Quartz)

- Speed bumps

- Intentionally slowing people down keeps them focused on the task at hand. Sometimes, a little friction can be a focus intervention. A speed bump might minimize risk. In a sign-up or payment process, this takes the form of a confirmation dialog. It might also prevent a mistake, the way touch ID prevents an accidental purchase on your phone. A speed bump might delay an action so that you can reconsider, too.

- Summary views

- A synopsis so that you can decide whether to go further. Think about Twitter’s While You Were Away feature. Rather than feeling frantic about catching up after being away for a day (or the last few hours), this summary gives us the opportunity to decide whether we have caught up or truly want to spend more time. Better still would be a way to understand and shape what we are shown as a summary, whether through a simple rating as we go along or a setting that we are prompted to revisit every so often.

- Do not disturb

- A feature that lets you check out for a while or detects when you are likely to want to do so. Plenty of standalone apps, like Offtime, have been introduced to help us focus for a while by tuning out tech-based distractions. Still other apps such as Slack have a Do Not Disturb mode that you can select as needed—kind of a descendent of email vacation notices. Apple recently added Driver Mode to iOS 11, as shown in Figure 5-8, detecting when you might be driving to automatically mute notifications.

Figure 5-8. A time-out, for our own good (source: Apple)

These techniques can give us the mental whitespace to interpret, understand, and add meaning to our experiences. Each involves our attention in a thoughtful way, potentially deepening engagement. This runs counter to current design practices to minimize friction. Rather than prompting people to constantly seek out what’s new and what’s next, focus techniques draw attention inward. By giving people room to make meaning, the experience potentially becomes more memorable.

SELF-MANAGEMENT ANTIPATTERNS

There are all kinds of antipatterns designed to hijack our attention. Rather than the dark patterns for signups and sales, these patterns are most often found on social media and other experiences fueled by advertising. The following are fairly well known:

- Bottomless bowls

- Visual cues that transform a finite experience into an endless one. This type of design pattern gets its name from an experiment in which participants were seated at a table, four at a time, to eat soup. The participants did not know that two of the four bowls were attached to a tube underneath the table which slowly, and imperceptibly, refilled those bowls. Those eating from the “bottomless” bowls consumed more than those eating from the normal bowls. Although the research itself has now come under scrutiny, the pattern is still relevant here. If the internet is our soup, the bottomless bowls are features like infinite scroll on newsfeeds and autoplay on Netflix and YouTube.

- Cliffhangers

- Any feature that compels us to continue out of curiosity about what’s next. Cliffhangers are not exclusively digital, of course. A cliffhanger is a plot device that ends with a precarious situation. Combine cliffhangers with full seasons released at once and autoplay, and it’s increasingly difficult to come up for air. Not that binge watching is always bad, but it would be better if we felt like it was our decision. Clickbait headlines and cleverly situated images in feeds, in which only part of the image is shown, work in the same way, turning intense curiosity from a positive into a negative.

As product designers and developers, it makes sense for us to take a hard look at how we design for attention. We should lift some of that responsibility from people who are trying to live their lives without putting technology on hold. These focus detractors make it easy for people to spend more time than they might intend to do. Minimizing the use of those design patterns will certainly help to restore focus.

Focus has been the main focus of digital mindfulness, digital well-being, and other related movements. That’s a good start, but there is more to emotional well-being than giving us back our time to focus. We also need to be creatively engaged in our lives.

Self-Catalyzing Interventions

Daniel Goleman’s model of emotional intelligence includes motivation as a facet. Rather than thinking about motivating people to buy or spend more time, let’s look at ways design might encourage people to self-motivate. Creativity is one way to do that.

POSITIVE SELF-CATALYZING PATTERNS

Creativity might not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of emotional well-being. Research tells us otherwise. Creativity is an act of self-discovery that gives us a feeling of competence. Creativity motivates us to learn and explore. Creativity involves a mix of intense positive and negative emotions—another hallmark of well-being. Most of all, creativity aligns with a deeply meaningful life.

From doodling to knitting to playing a musical instrument, creative engagement contributes to the upward spiral that is characteristic of happiness where one positive builds and expands on another. Great news for me. Now I can justify my obsessions with theme parties, bespoke Halloween costume design, and absurd collections of miniature objects and partially broken toy parts perfect for dioramas and speculative design workshops. But does it apply to technology?

The diaries of highs and lows that started this journey say “yes”; creativity is key. Even though it’s not surprising that people wanted to feel smart and respected, the role of creativity was a little unexpected but consistently evident. Not creativity with a capital C, such as writing bestselling novels and devoting oneself to critically acclaimed art, but anything from sharing microfiction on Twitter to creating a cosplay board on Pinterest to crafting a creative Amazon review.

After reviewing hundreds of these examples, I found that certain websites stand out as bastions of creativity—Tumblr, the dearly departed Vine, Reddit, YouTube, and Twitter. No matter the site, some patterns emerge. It turns out that how technology nurtures creative engagement is not so different from creativity in other contexts. Here are a few ways to cultivate creativity through design:

- Constraints

- Boundaries produce boundless thinking. Research on gaming illustrates that tough obstacles prompt people to open their minds to the big picture and make connections between things that are not obviously connected. It’s called global processing, a key characteristic of creativity. So as much as people might complain about the 280-character limit on Twitter, it prompts creative workarounds. Likewise for Vine’s 6-second clips. A good constraint outlines the right number of choices to get started as well as rules to work against.

- Identity controls

- Creativity flourishes when we can be flexible about identity. Identity is a kind of slider: we move from being anonymous to playing a role to being true to ourselves all the time. And creativity flourishes when people have control over their identity. Although people can feel creative in a variety of contexts online, creative expression peaks when we aren’t tied down to a “real” identity. Bitmoji, for example, encourages people to craft personal stories (Figure 5-9). That’s probably why Facebook isn’t the center of creativity; it’s where we share creative ideas that came from Twitter or Tumblr.

Figure 5-9. A balance of freedom and control (source: Snap)

- Remixability

- Shifting meaning in new contexts is a creative act. It’s that heady mix of conflict, clash, and divergence that inspires a fresh approach. Whether quotation, commentary, parody, or homage, remixing is a way to make sense of culture and put our own imprint on it. Reframing to produce a fresh perspective on the source or context was around long before the internet. Remixing has been traced from Shakespeare to Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. to Kutiman’s Mix the City, all the way to Kermit memes (Figure 5-10) and reblogging on Tumblr.

Figure 5-10. You’re probably skipping this section, but that’s none of my business (source: Know Your Meme)

- Chronological feeds

- Progression builds reinvention. When remix and dialogue is fundamental to creativity, well, chronology matters. To share and build off of one another, people need to see the progression. Personalized feeds, news, products, and videos make it more difficult to see the evolution and put your own twist on it. Of course, the other problem is that experience driven by algorithms is geared toward our past behaviors, ideas, and tastes. That can limit creativity as well.

SELF-CATALYZING ANTIPATTERNS

Creative engagement follows four stages: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification. Online, maybe it looks something like this: you see a friend’s post about Prince and then move on to Wikipedia for a timeline of the artist’s life, you listen to your favorite song, you hear something unique and new, and you get the urge to pull together a new playlist on Spotify. We can amp up this process with some of the positive interventions. We can also detract from creativity, if we begin pulling apart this process. Here are a few detractors:

- Misplaced automation

- Filling in the blanks discourages creative thinking. Autocomplete isn’t all that bad when you are filling out a form with repetitive details like address or phone number, but when it comes to autocomplete for comments, images, messages, and emojis, not so much. Automated prompts, when overused, curtail creative communication.

- Filter bubbles

- Limited exposure equals limited creativity. Personalization has its downsides. Google shows dramatically different search results based on our behaviors and other data, whether you’re logged in or not. Facebook’s algorithm tailors your newsfeed based on the posts you like and who you interact with, creating a de facto inner circle. It narrows our perspective, producing echo chamber effect. Rather than helping us feel more creative, the result can be the opposite.

Without exposure to broader inspiration from the outside world, creativity languishes. Despite the discomfort of stepping away from what you know, exposure to new ideas sparks questions. Of course, we can unfollow people who are too much like ourselves, talk to strangers, and volunteer. But our designs can support this, too. Buzzfeed added a feature called Outside Your Bubble, shown in Figure 5-11, which gives you a glimpse of what other people are posting and thinking. Although designed to expand our thinking politically, it also can inspire new ideas in other contexts.

Figure 5-11. Better for our creativity and for our culture (source: Buzzfeed)

Despite the general consensus that the internet is killing creativity, technology doesn’t need to be that way. Patterns that maximize curiosity, serendipity, and flexible identity can cultivate creativity in any context, motivating us to make our own meaning. Many of the patterns that cultivate creativity intersect with patterns for rapport, tolerance, and empathy, too.

Social Relationship Interventions

When it comes to forging strong social skills, generosity is key. Giving turns out to be better for your emotional well-being than getting. Giving makes us feel happy, so much so that when we give to charitable organizations researchers can actually see the effect. Giving activates regions of the brain associated with social connection and trust; altruistic behavior releases endorphins in the brain, producing a helper’s high. Besides delivering a bit of a natural buzz, giving is linked with a lot of other positives.

Giving promotes a sense of trust that strengthens our social ties. When we give to others, we feel closer to them and they feel closer to us, reinforcing community. Giving itself promotes a ripple effect of generosity. Researchers James Fowler and Nicholas Christakis found that cooperative behavior cascades on social networks.6 Altruism can spread by three degrees, so that each person in a network can influence dozens of others.

Giving evokes gratitude, and gratitude builds positive social bonds. People who are grateful are more open to new people and new experiences. Gratitude can even bolster self-control. Like all the other aspects of well-being we’ve looked at so far, it has a positive impact on physical and mental health, too. So how can we cultivate everyday generosity by design?

POSITIVE SOCIAL RELATIONSHIP PATTERNS

Why people act honestly, generously, and fairly is still something of a mystery. So far, no one has discovered a simple list of variables that predict generosity, yet it seems that we all have a capacity for it. Despite the unknowns, we can draw on some patterns to create generous interventions.

- Compassionate rehearsals

Trying out compassionate action can change minds and encourage altruism. Games potentially influence altruistic behavior, especially as we start to identify with the game avatar. Games for good, like The Cat in the Hijab (Figure 5-15), encourage people to rehearse compassionate action.

Figure 5-15. Trying out altruistic behavior, as a cat or not, might encourage more of it (source: Cat in the Hijab for ResistJam)

VR as a path toward altruism, compassion, and empathy is just starting to realize its potential. Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab studied how VR can encourage people to be more empathetic to the homeless. The simulation starts in your own home. You lose your job, struggle to make rent, choose items in your home to sell. Eventually, you are evicted and try living in your car. After your car is towed, you try to sleep on the bus, all the while guarding your backpack. Compared to study participants who only read statistics or even narratives about the homeless, people were more motivated to get involved.

But compassionate rehearsals or immersive empathy can lead to burnout and withdrawal. Whether you put on a headset or take part in another kind of simulation, you know that you can step away at any moment and go back to life as it was before. It’s temporary. Likely, as the experience loses its novelty, we will feel the force of it even less and need to up the ante. Like all of the interventions here, compassion rehearsals aren’t a cure-all but are certainly a promising start.

- Mushrooming

Change emerges from cultivating a vast underground of related actions. When I grew up in Michigan, I wasn’t sure whether the giant prehistoric fungus that flourished under the Upper Peninsula was myth or reality. No matter, what intrigued me was searching for evidence on the surface. Rebecca Solnit, in Hope in the Dark (Haymarket Books, 2016), memorably describes hope as that network of fungus under the surface that occasionally sprouts mushrooms.

Translated to a design intervention, mushrooming means showing how small actions come together to make big change. That’s why GoFundMe and Patreon feel empowering. Sites like Spacehack (Figure 5-16), a directory of projects related to space exploration, give people a way to contribute to something bigger by classifying photos taken by astronauts or transcribing logbooks or sharing the discovery of stars.

Figure 5-16. Hope springs astronomical (source: Spacehack.org)

- Positive amplification

- Positives beget more positives. If you’ve ever lived through a natural disaster, you know that most people are calm, resourceful, and altruistic. But you might hear much more about the bad behaviors—looting, violence, and despair. Negatives get our attention, and attention is currency on the internet, for now. Amplifying positive actions, conversely, cultivates hope. At first, Upworthy might have seemed a good example of inspiring posts about brave individual acts. But humans being humans, we habituate to the clickbait headline and gloss over the noble actions. However, stories on sites like Refunite, an organization that tracks missing refugees, and Micos, a microlending platform, haven’t lost their power to amplify.

- Creative gifting

- Spending time choosing a meaningful gift has benefits for the giver and receiver. Considering what makes a good gift can also reveal some possible patterns for giving. Marketing professor Russell Belk has extensively studied the emotional force of gift giving and has found that the perfect gift involves three variables: originality, personal fit, and sacrifice.7 Here we should look to kids, who are actively and inventively figuring out ways to create meaningful gifts using technology. Whether dedicated Pinterest boards crafted with a friend in mind, a playlist, or a drawing, we can learn from kids who seem more apt to apply creativity to giving. Creativity doesn’t need to be handmade, of course, but it shouldn’t be a default choice. The more thoughtful the effort and creativity, the better the experience all around.

In the end, almost all giving is good, but some is better than others. Automated monthly giving, a checkbox to add a $1 donation at the end of a checkout process, rounding up dollar amounts to donate to a favorite cause, and starting your shopping at Amazon’s Smile page are all convenient ways to give that have tangible benefits for charitable organizations. And all these activities can make people feel good, especially the first time out. As we know, what once made us happy isn’t going to last. By automating, we lose some of the positive effect on our own well-being over time. Perhaps that’s negligible, though, when we take the big-picture benefit into account.

SOCIAL RELATIONSHIP ANTIPATTERNS

Just as we don’t yet understand that much about what inspires generosity or altruism, we don’t know that much about what discourages it, either. Research on the virtues is surprisingly minimal. A few patterns that discourage generosity and social inaction seem to hold true, however. Let’s take a closer look at them:

- Dystopian rumination

Repetitively going over a dystopian narrative with no potential good outcome. By dwelling on negatives and replaying them, people become stuck in a cycle in which they are reinforcing anxiety or inadequacy. In the climate-change community, this is known as solastagia, or the existential distress many people feel about climate change. When we feel that there is no possibility for change, hope wanes. Consider this the tech industry equivalent of solastalgia.

What reinforces this pattern? High-pathos headlines like “When the robots take over will there be jobs for us?” and “Have smartphones destroyed a generation?” leave us longing for times past. We end up relying on coping mechanisms, like cynical posturing or sharing cute baby-animal GIFs, rather than action. Or, our reaction might be to agonize over what we can do without feeling like we are able to accomplish anything. Future Crunch’s newsletters and Gapminder’s data visualizations are examples of organizations trying to put the negatives in context of big-picture positives.

- Heaven’s reward fallacy

- A pattern of thinking where a person expects rewards for giving. Heaven’s reward fallacy happens when a person becomes bitter or angry if they feel a proper recognition was not received. So, although public recognition of gifts or donations is thought to encourage giving, it can paradoxically reinforce this negative pattern of thinking. Think about how leaderboards on sites like Kiva or Kickstarter can make us feel good and bad at the same time. Giving without expectation makes people happier in both the short and long term, but online altruism seems to focus on prompting people to give by ensuring that they will get something. That’s something we can flip.

Being part of something bigger than ourselves might be at the heart of generous social relationships. That overwhelming feeling of awe and communion empowers and disempowers at once. So, let’s add self-transcending to the traditional categories of emotional intelligence.

Self-Transcending Interventions

Think about a time when you’ve experienced awe. Maybe you were gazing up at a Georgia O’Keefe painting or looking down into the depths of an infant’s eyes. You might have found yourself lost in an inspiring performance of a favorite piece of music. Viewing a solar eclipse for the first time (with the appropriate eye gear, I hope), you might have felt humbled by the vastness of the universe. That sense of awe blurs you a bit at the edges and you feel a sense of communion with nature or other people, or just something bigger than yourself.

Our culture might just be a little awe-deprived at the moment. We spend more time working than we do out in nature or attending art events or participating in religious ceremonies. Our experience of technology doesn’t help in that regard. The internet, and all the technologies it pulls together, privileges narrow at the expense of expansive experience.

Awe is an emotional response, usually to something vast that challenges the limits of our current knowledge, by which we transcend ourselves. Awe gives us a sense that time is abundant and endless. And that seems to have all manner of tonic effects on well-being, including increased feelings of connectedness, heightened awareness of the strengths of others, a better sense of perspective on priorities, and an impulse toward altruism.8 Feelings of awe can also have an impact on how we spend, too. Rather than spending money on products, we’ll spend on experiences. On social media, awe is the one emotion that keeps pace with anger for viral effect.

No wonder that awe is one of the 10 positive emotions according to Barbara Frederickson’s research9 and transcendence is one of Martin Seligman’s 24 character strengths.10 All this sounds like a potential antidote to what’s wrong with technology’s pace, but our experience of the internet might be more Aww than Awe (yes, there have been academic studies of the effect of cat videos on happiness in case you were wondering). We might wonder at the latest new technology, but it isn’t quite the same as contemplating our spiritual connection to the universe. So, what can we do besides immerse ourselves in Shots of Awe on YouTube? Here are some ideas:

- Serendipitous intimacy

Serendipitous intimacy is a term I’ve come up with for a moment of random, maybe sudden, authentic connection. Like Sonja Lyubormirsky’s random acts of kindness intervention, it’s sometimes associated with a helper’s high—that amazing feeling we get when we’ve helped in a real way. Be My Eyes, an app that draws together sighted people with those who have impaired vision, is my touchstone example (Figure 5-17). The real-life equivalent would be gatherings like Tea with Strangers or Death over Dinner, perhaps.

Serendipitous intimacy is more than random closeness; it’s that plus meaningful communication. That’s what separates, say, the CNA Language School from Chat Roulette. It’s experiencing the vast wonder of humanity in an intimate moment.

Figure 5-17. Wonder not at the tech itself, but at communion (source: Be My Eyes)

We can find wonder in intimate connections, but more often we think of it as a view that’s big picture—really big picture. Just last fall, as I was checking in to the Web Summit conference, I struck up a conversation with another speaker at the desk. We chatted about the conference a bit. Then, I asked what he was speaking about. Oh, he just happened to be an astronaut and was talking about NASA. No big deal. If I’d had my wits about me, I might have asked about the experience of seeing firsthand the reality of Earth in space. Lucky for me, I caught Michael Massimino’s talk later, during which he mentioned the overview effect right after he talked about sending the first message on Twitter from space. Maybe that’s an awe spiral.

- Overview effect

- A profound cognitive shift in awareness that induces a sense of wonder. The wonder of seeing Earth as a tiny, fragile ball of life hanging in the void becomes a deeply transformative experience of unity with nature and universal connectedness. The overview effect is experiencing the vast wonder of humanity by taking it all in at once. Because we can’t all travel to space just yet, how can we facilitate the emotional power of the overview effect through design? IMAX theater, virtual reality, or immersive games might temporarily facilitate this particular kind of wonder.

- Synesthesia

- A crossed response of the senses that confounds and intrigues. The most common form of synesthesia is grapheme-color synesthesia, in which people perceive individual letters of the alphabet and numbers to be tinged with a color. Other synesthetes commingle sounds with scents, sounds with shapes, or shapes with flavors. Small children seem especially prone to it. The perceptual mashup can be overwhelming, but it can also bring a sense of wonder. I’ll offer the iTunes music visualizer as exhibit A—a blend of music and visuals, a strangely mesmerizing early-day tech experience that cultivated a transcendental state. The Fantom app, released by trip hop artists Massive Attack, is a current example (Figure 5-18). The app encourages people to remix sound with other inputs from sensors and accelerometer in a sensory mashup.

Figure 5-18. Synesthetic remixing (source: Fantom)

Just as synesthesia offers up new associations, well-placed randomness can also foster that sense of awe. Unexpected juxtapositions encourage us to bring together new associations and see the world writ large. Sometimes, we can achieve this by stumbling around the internet on our own; sometimes it’s expertly crafted.

We are only just beginning to consider technology and awe. Anthropologist Genevieve Bell has considered spiritual practices facilitated by technology, ranging from virtual confessions to texting messages at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem. Elizabeth Buie of Northumbria University in Newcastle, England, has been studying how technology can facilitate transcendent experiences. In the Enchantment of Modern Life (Princeton University Press, 2001), philosopher Jane Bennett considers all manner of wonder in everyday experience.

The positive interventions to try, and the negatives to avoid, are just a start at identifying design patterns that we can use to support emotional intelligent technology. These factors overlap and intersect in all kinds of ways. Much more work is needed to develop practices that we can adopt. In the meantime, we can begin to assess the impact.

Track Progress

For those who like to track progress, a simple rating system can help. Here, the inspiration comes from well-being measures that track progress on multiple factors. If we have some factors that we know have a positive or negative impact, we can also assess how well we are achieving those goals.

Start with the model here, grounded in emotional intelligence. Or consider another like Happify’s SAVOR. Or develop your own. For each, we can track three (or five, if you want to get more specific) levels:

- Negative (active or passive)

- A negative impact on physical, emotional, or mental well-being is detected, either on the level of an individual or collectively. To get even more granular, you could distinguish between two levels of negative impact: actively pursuing a negative impact (usually for a business reason) or passively by inadvertently employing a pattern that subverts well-being for a lot of people.

- Neutral

- Known negatives are phased out or not used at all, but positive strategies are not employed for the value either. In other words, it doesn’t detract, but it doesn’t add much either.

- Positive (explicit or implicit)

- A positive impact supports social and emotional well-being. Here, there could also be a split between products: those for which the core purpose is supporting well-being, and those for which well-being is implicit.

If you plotted these factors on a chart, it might look like Figure 5-19.

Figure 5-19. The contours of an emotionally intelligent experience

Of course, we want to embrace all of these factors when we are developing new technology, but it might be that different types of experiences have different shapes. The intent is not to be reductive, but to make progress toward removing negatives at minimum and planning for positive outcomes. This applies not just to products explicitly designed for mental and physical health, but to all tech, from social media to wearables to news sites to workplace applications.

The first goal is to move out of the negative zone, which probably won’t be easy. Why? Because some negative patterns are good for business. And further complicating matters, some negative patterns might not be negative to everyone all the time. People are inventive in how they bring technology into their everyday lives, as we all know. So, consider these guidelines more than hard-and-fast rules.

Interventions Bolster Emotionally Intelligent Design

A lot of the best thinking about design for emotional well-being has emerged from the design of cities, from Jane Jacobs’ work in New York City to Christopher Alexander’s pattern language for building to Terrapin Bright Green’s biophilic design. There is no formula for a happy city, but it has to include the right elements—mixed-use blocks, green spaces, fewer cars, and more bike paths. And that’s not enough. It all needs to work together.

The interventions here are a way to lay the foundation, no matter the experience—nonprofits, government organizations, big corporations, or scrappy startups. And none of these interventions necessarily require permission from the top down to enact. Perhaps these micro-level interventions will prove even more effective than a macro-level statement of values and the more recent introduction of regulations.

After all, many big companies and other organizations have grand mission statements that are sometimes at odds with their actions. Corporate social responsibility departments often find themselves trying to offset the compromises made to mission. As individuals, we find ourselves at a loss about how to change minds, whether our own or those of others. What if we balanced sweeping statements with small goals? By putting these small changes into our repertoire, we can make tech more emotionally intelligent.

1 Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein.,Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Yale University Press, 2008.

2 Martin Seligman, “Empirical Validation of Interventions,” American Psychologist, July–Aug 2005.

3 Claudia McNeilly.,“The Psychological Case for Instagramming Your Food,” The Cut, March 7, 2016.

4 Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert, “A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind,” Science, November 2010.

5 Marco von Bummel et al., “Be Aware to Care: Public Self-Awareness Leads to a Reversal of the Bystander Effect,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, July 2012.

6 James Fowler and Nicholas Christakis, “Cooperative Behavior Cascades in Social Networks,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, December 28, 2010, p.107.

7 Russell Belk, “The Perfect Gift,” in Gift Giving: A Research Anthology , ed. Cele Otnes and Richard F. Beltramini, Bowling Green University Press, 1996.

8 Melanie Rudd, Kathleen D. Vohs, and Jennifer Aaker, “Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time and Enhances Well-Being,” Psychological Science, December 2010.

9 Barbara Frederickson, Positivity, Harmony Books, 2009.

10 Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman, Character Strengths and Virtues, Oxford University Press, 2004.

Social Awareness Interventions

In most models of emotional intelligence, social awareness—empathy—is central. Empathy is ultimately an act of imagination. It means viewing the world from another perspective and using that understanding to guide our actions. Considering that relationships are the underpinning of a good life, empathy is enormously important.

Yet we hear conflicting research about empathy. Empathy is waning in young people, a development attributed to the smartphone with varying levels of shrill urgency. Then again, empathy might not be that great anyway according to Paul Bloom (Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion [Ecco, 2016]), leading us to prioritize the needs of one person rather than thinking about the greater good.

The arguments are also playing out in the design community. Empathy, foundational to design thinking, has come into question. There are limits to how each of us, working in our own bubble, can reasonably hope to empathize with such a wide range of people. Ethnographic research, our go-to approach for immersive empathy, is a phase that is often skimmed or skipped altogether. Then, there’s the uneasy place empathy occupies between going with your gut and going with the data.

I’ll go with the Dalai Lama on this issue. Let’s reaffirm the need for empathy, of all kinds. What we need now, and always, is understanding, perspective, kindness, and compassion. Affective empathy helps synchronize us with other’s emotions. Cognitive empathy helps us to be less judgmental. Empathy is a way toward well-being. It has a real impact on physical and mental health. Even more so, empathy is the underpinning of community.

Although empathy can come naturally to many of us, few among us have reached our empathetic potential. Certainly, we try to cultivate our own empathy as designers, mostly through research. So, how can we design technology to better facilitate empathy among others?

POSITIVE SOCIAL-AWARENESS PATTERNS

Because strong relationships are so critical to happiness, there’s no shortage of inquiry into how to cultivate empathy and compassion. A few patterns emerge:

More time spent in meaningful conversation translates to empathetic understanding. People who engage in discussion about the state of the world and the meaning of life seem to be happier than those who spend their time talking about the weather. It might seem counterintuitive. I mean, staying on the shiny surface could seem less troubling than plumbing existential depths. Because humans have such a strong drive to create meaning and connect with other people, however, substantive conversation does contribute to our sense of well-being.

Conversational depth relies on a push and pull between discovery and synthesis, seeking and coherence. A good conversation is open-ended, emotionally resonant, and distraction-free. And it requires time. Sherry Turkle writes in Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in the Digital Age (Penguin, 2015) about the informal seven-minute rule—that it takes seven minutes for a conversation to unfold.

Conversely, many of our tech-mediated conversations seem built for shallow interactions. Whereas Slack is useful for a quick check-in, it’s not great for a sustained conversation; the same goes for other social platforms for which staying in touch, rather than the quality of the conversation, is the endgame. Conversation online suffers not only from a lack of undivided attention and lack of emotional cues, but also from cognitive distortions unique to internet experience. The performative aspect of conversation is inflated on social platforms, too. The sense that you are speaking to an audience changes the tone of the conversation.

We can certainly choose to use social media in a way that supports conversational depth. I use birthdays, the only chronological aspect of the experience, as a reminder to engage in conversation. Many people use FaceTime or Skype to have a conversation, so much so that the American Association of Pediatricians have given the greenlight to video-chat apps at any age. Quora, despite its Q&A format, gets close to this sometimes. However, we could also build technology toward meaningful understanding as opposed to gathering information or broadcasting a message or quickly checking in.

Engaged presence nurtures affiliation. Whether you’re phubbing your colleagues on a video chat or surreptitiously picking up your phone at the dinner table, something about the current design of our favorite technology discourages presence. And yet we know from years of research that engaged presence is what sustains relationships.

For a time, I engaged in a little data collection project in which I sketched people looking at their devices in public places like airports, school concerts, and doctor’s offices. I learned two important things: people are not looking at their devices as much as we think they are and many people are happily passing devices between them. Couples, and kids especially, seemed to enjoy a kind of copresence.

Maybe this is where we follow the teens’ leads. Some of the most popular apps teens use are geared toward engaged presence. Houseparty is a current favorite in my house to host real-time group chats (Figure 5-12). As much as we might like to complain about Snap or Kik, they can underpin creative, engaged, and, yes, even sustained conversations. Airtime is just one of many new apps springing up that let people share photos, videos, and music in a video chat.

Figure 5-12. Conversation isn’t dead, it’s just shifted (source: Houseparty)

In urban design, well-being emerges from mixed-use blocks. Rather than blank stretches of big-box stores, researchers find that people are more likely to have casual conversation and spend time together when there is a lot of variety. William Whyte discovered, through time-lapse observation, that people cluster around busy entrances rather than isolated corners. When it comes to neighborhoods, people prefer a bit of a jumble.

Whether you call it weak ties or consequential strangers, these porous spaces reinforce empathy at a community level. Pokémon GO faded fast from our collective consciousness, but the most lasting and genuine aspect of its success was as a bridge between neighbors. Suddenly, kids were hanging out in their neighborhood with other kids. People welcomed new visitors to their neighborhood haunts. Similarly, CNA Speaking Exchange pairs Brazilian students with seniors at Windsor Park Retirement Community in Chicago. The program is dual purpose: help students learn English and bring conversation into the lives of the elderly in the United States.

Exposing people to different perspectives can cultivate greater tolerance. In social psychology, the contact hypothesis shows that prejudice is reduced through extended contact with people who have different backgrounds, opinions, and cultures than our own. Developed by psychologist Gordon Allport as a way to understand discrimination, it is widely seen as one of the most successful tools for increasing empathy.

KIND’s Pop Your Bubble project matches people with several individuals who have opposite points of view. It prompts you to follow Facebook users who have been identified as your opposite for geographic location (urban vs. rural), age, hometown, and previously liked and shared content. There’s no pressure to like or comment, but even so a personal connection can develop.

Authentic connection relies on mirroring. In Enchanted Objects (Scribner, 2015), David Rose envisions an enchanted wall of lights visualizing the moods of your loved ones. That future might not be far off. British Airways recently gave passengers flying from New York to London blankets embedded with neurosensors to track how they were feeling (Figure 5-13). When the fiber optics woven into the blanket turned red, flight attendants knew that the passengers were feeling stressed and anxious. Blue blankets were a sign that the passenger was feeling calm and relaxed. So, the airline learned that passengers were happiest when eating and drinking, and most relaxed when they were sleeping. I wonder about the effect on passengers, given our tendency toward social contagion.

Figure 5-13. Happiness is a sensor-warm blanket (source: British Airways)

Although emotion-sensing technology can mirror, it’s not the only way to do so. If I am trying to feel connected with my partner across long distances, I might share a heartbeat on my Apple smartwatch. There’s even the awkwardly named Kissinger, which sends a physical kiss across a network. Whether it’s sharing data about our stress level with a partner or posting images to express joy, technology can facilitate attunement. Empathetic technology, especially when aimed at cultivating empathy between people rather than reinforcing dependencies on products, could be a force for good. Just as often, though, we encounter the negative patterns.

SOCIAL AWARENESS ANTIPATTERNS

Way back in the early aughts, John Suler published the Psychology of Cyberspace, in which he laid out several cognitive distortions related to digital identity. More than a decade ago, it was clear that our relationship to one another online was not quite the same as, in the parlance of the time, meatspace. Here are a few examples of those cognitive distortions:

The feeling that you don’t need to take responsibility because you are anonymous. Despite the success of late-night talk show hosts reading out mean tweets, some people feel that they don’t need to own their behaviors online. People might convince themselves that their actions “aren’t me,” which is dissociation in psychological terms. Dissociative anonymity is linked to content vandalism, doxing, cyber-bullying, stalking, and trolling.

This isn’t to say that anonymity doesn’t have a place. The same freedom you might feel traveling alone in a new city can encourage you to play with your identity. When people can separate their actions from the “real world,” they feel less inhibited about being vulnerable. Anonymity can also be a safe space for people who are excluded. And for everyone who wants to experiment with identity once in a while or talk without being tracked.

So, how do we cultivate good anonymity and decrease the bad by design? This is the question most platforms struggle to figure out. So far, there have been a few approaches to counter the downsides of anonymity, trolling, and bullying in general. The Wikimedia Foundation uses supervised machine learning, in which human moderators train AI to filter with more precision. Another strategy is to enlist the public to report harassment. ProPublica has implemented a secure whistleblower submission system. Yet another is to give people more control. Instagram has recently added comment control to let people decide who can and can’t comment on their posts. Still, it’s a struggle.

A diffusion of responsibility based on the presence of a real or imagined group of observers. The more we think other people are present, whether visible or not, the more likely we are to assume that someone else will step up, online or off. Just in the past year, people have failed to intervene in livestreamed torture and suicide. But every day we see less horrific examples, too. A lonely cry for help in a Slack channel, where many can help but no individual feels an obligation to respond. The email sent to the group that everyone reads but no one answers.

The antidote to bystander effect might be public self-awareness. When we sense the group is aware of us personally, we are more likely to take positive action. A group of Dutch psychologists led by Marco van Bommel showed that highlighting an online community member’s name in red made people more likely to intervene in an online request for help. In brief, you know that other people know you are there.5 Perhaps it’s purely out of concern for reputation, or perhaps it’s simply a wake-up call.

Besides just making people feel present, we can nudge a little as well. Quora addresses lonely questions by suggesting individuals who could answer the question, as shown in Figure 5-14.

Figure 5-14. Gentle nudges for help (source: Quora)

Obviously, people shouldn’t be solely responsible for monitoring one another on social media. Social media platforms need to develop more intelligence to detect trolling, livestreaming of crimes, and other abuse. The moderation process needs to be more transparent. Over-reliance on human moderators, who can be traumatized by the work, needs to be addressed. Online harassment has too few consequences, or easily circumvented ones, for harassers and too many for its victims and moderators. That needs to change.