Chapter 3. Designing, with Feeling

RUMMAGING AROUND IN THE clutter of handouts that comes home from school, I stumbled on an alarming article in my youngest daughter’s welcome packet, “It’s Digital Heroin: How Screens Turn Kids into Psychotic Junkies.” Although I certainly struggle with parenting in the digital age, I was taken aback by this high-panic pathologization of technology. Naturally, I tried Facetiming my middle school daughter, just in her room upstairs. No answer. Then, I texted my oldest daughter also at home somewhere. At first three dots, and then nothing.

Eventually, I found the same blurred and crooked photocopy in each packet—elementary school, middle school, and high school. When I sampled the opinion of other parents, no one gave it a second thought. When we think about the most vulnerable among us, emotions are laid bare. Smartphones make kids feel stressed, envious, depressed, and inadequate. Everyone knows that technology makes you feel horrible, I was told. But I wasn’t so sure.

This was a turning point for me. And, as a researcher, I approached it in the best way I knew how. Thousands of diary entries and hundreds of interviews later, I noticed how difficult it is to find a “good” experience that isn’t emotionally complex. A smooth process, once appreciated, was soon taken for granted. Rarely did I see mention of the little blips of delight we diligently design. When people described their highs and lows with technology, it was with mixed emotions. Often the most satisfying tech use tied to something bigger—a better version of themselves, an authentic connection, an engaging challenge, contribution to community. The emotional texture was not simply happy or sad, overwhelmed or calm. It was all of those simultaneously plus many, many others.

Yvonne Rogers, director of the University College London Interaction Centre, calls this technology for engaged living, or “engaging experiences that provoke us to learn, understand, and reflect more upon our interactions with technologies and each other.”1 As a complement to calm technology doing things for us in the background, it’s technology that no longer plays a purely functional role but social and emotional roles.

In this chapter, we consider emotional intelligence and its implications for technology. Rather than a new framework, what you’ll find in this chapter is a mashup of emotional intelligence and design thinking. Rather than designing for task completion or moving people toward a goal or even building habitual behaviors, it’s designing with emotion. But that doesn’t mean we’ll always design to make people feel a certain way. Here, we look at ways to build emotionally sustainable relationships with technology and one another.

Emotionally Intelligent Design Principles

Emotional intelligence is a gateway to a balanced life. People with high EQ are more likeable, empathetic, and more successful in their careers and personal lives. People who are a bit deficient when it comes to EQ are often unable to make key decisions in their lives, keep jobs, or build relationships. Even setting broad claims and myriad studies aside, it’s common sense. If we can understand and work with, rather than against, our own emotions and those of others, the outcome is positive.

The idea that emotion is integral to intelligence is age-old. From Plato to Proust, Spinoza to Sartre, Confucius to Chekhov, emotion is a way to make sense of the world and ourselves. The concept of emotional intelligence, as we know it, has been in circulation since the 1960s. Daniel Goleman’s bestselling 1995 book, Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ (Bantam Books) popularized the idea at a time when IQ was the prevailing standard of excellence. Emotional intelligence is not just being emotional or feeling feelings, though. Emotional intelligence is recognizing emotion in yourself and others and managing those emotions in meaningful ways. It’s usually summarized like so:

-

Self-awareness, or how accurately you can recognize, understand, label, and express emotion. Most often associated with self-compassion, self-esteem, and confidence.

-

Self-management, or how well you can regulate your own emotion, which usually includes discipline, optimism, and resilience.

-

Social awareness, or the ability to recognize and attempt to understand the emotions of others. Also known as empathy but encompassing tolerance and rapport.

-

Social skills, or how well you can respond to the emotions of other people. This translates to vision, motivation, and conflict resolution.

Although Goleman’s model is the most widely known, it’s really a mix of two approaches. The ability model, advanced by Peter Salovey and John Mayer in the 1980s, emphasizes how people perceive, understand, and manage emotions.2 The trait model, based on the work of K. V. Petrides, says that emotional intelligence develops out of personality traits. Despite the variation between different models, each approach is more about emotional competencies than moral qualities.

To effectively reason, plan, and perform tasks (all things we think of as cognitive), human beings need to have emotional intelligence. It means managing feelings so that they are expressed appropriately and effectively. It means handling interpersonal relationships fairly and with empathy. It affects how we manage behavior, navigate social situations, make personal decisions, and work with others toward common goals. And emotional intelligence, whether you consider it more about personality traits or more about ability, can be cultivated.

That’s just what many organizations are trying to do. In schools, social and emotional learning (SEL) is core to many curriculums teaching ways to cope with emotional distress and pro-social behavior. Leading the way is the Yale School of Emotional Intelligence with its RULER model for emotional intelligence: Recognizing, Understanding, Labeling, Expressing, and Regulating emotion.

Companies take it seriously, too. Emotional intelligence has been identified as a core skill for the workforce in the next 50 years by the World Economic Foundation. Companies from Zappos to FedEx provide leadership training with emotional intelligence as a core component. Organizations rely on tools like Culture Amp and Office Vibe to foster emotionally intelligent workplaces. Starbucks employees learn the LATTE method to respond to negative emotions in positive ways: Listen to the customer, Acknowledge their complaint, Take action to solve it, Thank them, and Explain why it occurred.3

So, what would happen if we applied the principles of emotional intelligence to design?

First, it would need to start with the organization. Right now, few organizations recognize how much emotion matters. Those that do tend to make the same mistakes. Many don’t factor in emotion at all. Or they rely on weak substitutes, like Net Promoter Score or behavioral metrics. Others go straight for a desired emotion, without trying to understand the context. Or they focus on evoking emotion in the moment, without thinking about the long term. Often organizations focus too much on one emotion, like delight, without thinking about other emotions that create value and meaning.

Then, it would need to be supported with a method that encompasses new ways to recognize, understand, express, evoke, and sometimes cope with emotion. It could certainly bring in new technology, too, employing emotion AI to help sort it out. It would mean expanding our repertoire to account for a more diverse range of emotional experience. Let’s begin with a new way of approaching emotion.

ADOPT A NEW MINDSET

Emotionally intelligent design starts from a mindset that considers emotion as intrinsic to the experience, not a nice-to-have extra. Whether we intend it or not, we already design emotion and build relationships. Where emotional design strives to create products to elicit an emotion, emotionally intelligent design builds emotional capacity. Designing products and services through the lens of emotional experience can make the experience better for everyone. First, a few guiding principles:

- Learn from emotion

-

Empathy is already a critical aspect of design, but that hasn’t always translated to emotion. Learning about our emotional life with technology and other products means spending time understanding the full scope of emotion. When done well, it’s more than evoking emotion. Emotions are clues to what we value. Fear tells us that something important is threatened. Sadness might remind us of what’s been lost. Shame might indicate that we haven’t been living up to our own goals. Values, in turn, guide behavior, motivate toward action, and prompt judgment.

It’s not a one-to-one mapping. It’s not always the same. But it’s important that we pay attention whether or not we are in it for the long term. Value-Sensitive Design (VSD), developed by Batya Friedman and Peter Kahn at the University of Washington, intersects with emotionally intelligent design. A core principle for VSD looks at who will benefit and who will be harmed, considering tensions between trust and privacy, environmental sustainability and economic development, and control and democratization. If we are paying attention to emotion and translating what it means, it can work in tandem with VSD to identify values, explore tensions and consider trade-offs.

- Embrace complexity

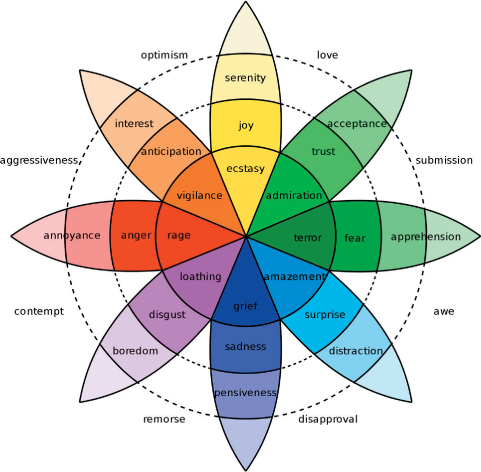

- Our inner lives are beautifully complex, yet even the most emotionally intelligent among us tend to translate what we feel into just a handful of emotions. What we need to develop our emotional intelligence isn’t fewer concepts, but more (Figure 3-1). Likewise, what we need to design emotionally intelligent tech is to embrace complexity in our work. Think about the most meaningful, emotionally satisfying, personally compelling experiences, and you’re likely to find mixed emotions. This doesn’t mean making design complicated, but instead creating rich experiences.

Figure 3-1. Core emotions unfold into a spectrum (source: Atlas of Emotions)

- Build a relationship

- Designing for fun is…well, fun. A pop of joy can certainly make a difference in your day. That’s emotion in the short term, and that can be significant. That view tends to focus on the emotion itself as the destination. Emotional intelligence takes a longer view. It means thinking in terms of relationships over experiences. As our products develop more intelligence about us, we will expect more. That means evolving emotional connections over time by studying how emotions, behaviors, and decisions form into lasting relationships. And it means making a leap to consider relationships with products and organizations and institutions as not just desirable for business, but worthwhile for all.

- Be inclusive

- Psychology has largely been the product of North America and Europe. So much so that more than 90% of psychological studies are WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic).4 Consider that the preponderance of studies that rely on college undergraduates, and you have just a tiny slice of our psychology. The study of human emotion has mostly evolved out of knowledge of a small part of the world. Clearly, humans share basic physiology and some fundamental needs. We no doubt share some core affect. Whether you argue that we share only a high-level binary of positive and negative affect as some neuroscientists do, or that we share five to seven basic emotions, as evolutionary psychologists argue, it’s not the entire story. The emotional texture of our experience is more nuanced. It’s on us to bring more diverse voices into the process, which has benefits beyond emotionally intelligent design.

- Consider scale

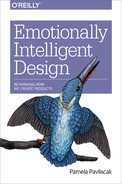

- Emotions are contagious. Your emotions will trigger another’s emotions, and so it goes. Although it seems like emotional contagion spreads more readily face to face, where we can see emotion, that just isn’t the case. There are emotional signals all around us that send emotions ricocheting between people, through communities, in cities (Figure 3-2) and around the world. Reading emotional climate without losing individual nuance and tracing the pathways without losing the thread will be vital to consider emotion at scale.

Figure 3-2. The emotional climate of a city, aggregate and individual (source: Christian Nolde)

- Be sensitive to context, always

- Picking up emotional signals is just that: signals. Clues about emotions. After all, feeling angry is not the same as flaring your nostrils and yelling. Even if there are patterns in appearance, that emotion might not be felt in the same way. Emotions certainly won’t be expressed the same way either. Anger online is expressed much differently than anger at school or at home. Emotions shift in cultural and historical context. Loneliness today is considered much more negative than in times past. Belonging in present-day America shares little resemblance to a similar suite of feelings in Japanese culture. Context changes everything. Without sensitivity to context, there’s no real path to emotional intelligence.

With something as deeply personal and wonderfully nuanced as our emotional lives, it’s clear that we need to take care. Prioritizing emotional experience is not just a different mindset, it affects how we practice design.

SETTING NEW GROUND RULES

When we focus in very narrowly on someone in the moment of interacting with a technology—a user—our current approach works well enough. Even looking at a customer’s journey, hopping from one business touchpoint to another, we might feel comfortable with current methods. But when we expand our view to consider a broader range of human experience, it becomes trickier.

If we look at anthropology, the tension between being a participant and an observer is acknowledged and discussed. That’s a healthy conversation for our field to have, too. As an observer, you change the power dynamic. Rather than people framing the experience in their own way and telling their own story, the observer ultimately gets to be the storyteller. As a participant, you lose a bit of that outsider perspective. Either way, you change reality a bit. Let’s set some new ground rules.

-

Lead by example

- Check your bias

- Even trained emotion coders will disagree on which emotion or how much emotion is expressed. People just do not see emotions in the same way. We have unconscious biases that lead us to draw different conclusions based on the same information. The emotions we detect might reflect us just as much as they reflect other people or the system. Machines will exhibit bias, too. Partially because of human bias in creating the system, and partially because of newly created bias in how emotion is interpreted.

- Be aware of stereotypes

- Women might describe themselves as more emotional, especially when you ask retrospective questions, like “How have you felt over the past week?” But gender differences rarely show up in experience sampling, according to Lisa Feldman Barrett in How Emotions Are Made (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017). Likewise, emotion-sensing tech doesn’t always register differences on a gender divide, and the same is true when it comes to race. There’s a huge body of research on emotion and stereotypes, which you can pore over. Or, you can simply commit to questioning stereotypes and do good product research.

- Let yourself be vulnerable

- Some of emotion research is detecting what we normally observe in others—an expression, a gesture, or a tone of voice. It’s visible, and it’s open to (your) interpretation. If you choose to go further than that, you’ll soon learn that it’s a give and take. Should you decide to have those conversations, know that you’ll need to reveal a bit more about yourself than you might otherwise do.

-

- Participate as equals

- Researchers favor the observer position. Implicit is the belief that “people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” That mindset doesn’t give people nearly enough agency. I’d rather see how we can creatively engage people to shape the future with us. Many organizations are leaning toward a participatory approach already, with design team members as equal participants, not leaders.

- Respect boundaries

- If we are going to be a little more personal, we need to respect boundaries. All of the same guidelines we have for research already around privacy hold true, of course. We need to hone our skills to listen for verbal cues, whether obvious or subtle. Training in body language is essential. Knowing your own personal boundaries is a given. As we develop a wider range of participatory research methods, we need to honor any and all contributions.

- Think post-demographic

- Demographics, whether traditional age and gender breakdowns or behavioral categories like shopping habits, cast people in broad strokes. Demographic or behavioral data inherently aim to predict what people will do in the future based on stereotypes. Besides veering toward caricature, demographic categories are slippery. Gender is a spectrum, age is often unmoored from typical attitudes or behaviors, “techiness” is constantly in motion.

-

Develop a shared understanding

- Develop an emotional vocabulary

- Emotions are, in part, concepts that we learn. Sometimes, we pick them up as part of our culture; sometimes, we’re taught; sometimes, we transmit them from one person to another. Most of us do not excel at talking about emotion, but it’s a skill we’d do well to develop. Practice becoming more specific in your vocabulary and adding new emotion concepts to your repertoire. There are endless lists and emotion maps to build a common language, like the Dalai Lama’s Atlas of Emotions, or T. U. Delft’s Negative Emotion Typology. Try out an emotion tracking app, like my favorite, Moodnotes (Figure 3-3), to help you develop your own sensitivity.

- Offer multiple ways to participate

- Design thinking has opened up a new world of collaborative activities around making. Empathy exercises are no longer rare. But let’s not stop there. Emotion is often best understood indirectly, which means developing new ways to prompt stories. Emotion is often private and personal, which means balancing think aloud with think alone, group brainstorm with singular contemplation.

- Listen empathetically

- The best listeners don’t just hear; they make the other person feel heard. To understand emotion is to home in on emotional undertones in language. It involves tuning in to body language and nonverbal cues. It might mean mirroring the mood of the speaker. More than just reflecting back, it also means showing care and concern.

Figure 3-3. Emotionally intelligent tech needs emotionally intelligent designers (source: ustwo)

What this really comes down to is a shift in perspective. We’ve created methods to understand behavior, but we’ve neglected emotion. Behavior can be observed much more readily than emotion. Either way, we see only the tiniest slice of real life. As technology insinuates itself into more facets of our everyday life, we need to facilitate more ways to understand how it affects our inner world as much as our outward behavior.

Design Feeling in Practice

Now that have some new principles for emotional intelligence in design, let’s put them in action. Next, we need a method. Design thinking is not perfect, but it’s widely practiced and easy to follow for designers and nondesigners alike. And it’s readily extensible to new contexts. For instance, Microsoft’s Inclusive Design process, under the leadership of Kat Holmes, follows five phases similar to a design thinking process: get oriented, frame, ideate, iterate, and optimize. Likewise, IDEO’s Circular Design Guide to sustainable design merges Kate Raworth’s thinking in Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (Chelsea Green, 2017) with design thinking in four phases: understand, define, make, and release.

Here, we merge emotional intelligence and design thinking. Should we call it design feeling? Or simply emotionally intelligent design? I’ll leave it to you to decide what feels most comfortable. Let’s use the following model for design feeling, with the easy-to-remember acronym FEEL.

-

Find, understand emotion in multiple dimensions using mixed methods.

-

Envision, map emotional experience and generate concepts.

-

Evolve, model and build relationships.

-

Live, develop ways to sustain the relationships.

You can observe the following as a step-by-step process. Or, you can supplement your current design practices with some of the ideas and activities. The core idea is the same—to design with greater emotional intelligence.

Find Feeling

Empathy is essential to emotional intelligence. The concept stands in for a wide range of experiences, but usually it means both the ability to sense other people’s emotions and the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling. The split between two types of empathy—affective empathy and cognitive empathy is contentious, though.

In our field, the emphasis has been on cognitive empathy. When we talk about empathy, we usually mean curiosity and perspective taking. In Practical Empathy: For Collaboration and Creativity in Your Work (Rosenfeld Media, 2015), Indi Young makes a point of differentiating between the two, finding cognitive empathy more useful for design.

Cognitive empathy gets us only so far, though. All we have to do is look at some of the current tech products on the market to test the limits. For example, the team who proposed a smartphone-enabled vending machine called Bodega designed to replace actual bodegas, almost certainly ticked off “empathy” in their design sprint, interviewing potential customers and possibly looking at behavioral data. And yet the proposed concept lacked emotional empathy.

In other areas of life, cognitive empathy is not enough. If you try to understand another person’s point of view without internalizing their emotions, you’re still detached. This can manifest in all kinds of ways. It might mean that you can’t understand another’s perspective. It might mean that you simply aren’t motivated to help. It might mean that you don’t fully realize the impact of your own behaviors on others. Take it a little further, and you’ll find narcissists and sociopaths who use cognitive empathy for their own gain, whether to manipulate opinion or inflict pain.

When you begin to allow yourself to feel what other people feel, that’s emotional empathy. It attunes us to another person’s inner world. And it even has a physical force, as emotional contagion activates mirror neurons in our brains, creating a kind of emotional echo. Emotional empathy has serious downsides, of course. It can lead to distress and physical exhaustion, so much so that certain professionals experience emotional burnout. Social, medical, and rescue workers can’t afford to let emotional empathy overwhelm them, but they’ll provide poor care without it. It’s not much of a stretch to see how that applies to designers, too.

In truth, we need both kinds of empathy. We need to understand what people are going through and to feel their emotions (to a degree). In some circles, this is called compassionate empathy. Whatever the case, it means expanding our repertoire.

MORE MIXED METHODS

As the first step in a design thinking process, empathy doesn’t always home in on emotion. Designers have developed keen observation skills but train their sights on individual behaviors. Emotions are more of an afterthought.

It’s not that observational methods can’t get at emotion. After all, we observe emotion in others all the time. High EQ is associated with how well you can notice subtle facial expressions and changes in tone and then interpret those signals. Emotion AI is trained to work in the same way, although in much broader categories. But there are limits to observation when it comes to emotion, too.

Observation can reveal truths but sometimes misses subtleties. Technology creates barely detectable shifts in behavior that can’t always be easily observed. If you are observing only a few people, you might not pick up on workarounds or adaptations. Because we train our sights almost exclusively on people acting alone, we might miss social dynamics. New gestures or expressions, even given the wonders of AI, go undetected. Emerging contexts of use are not always evident.

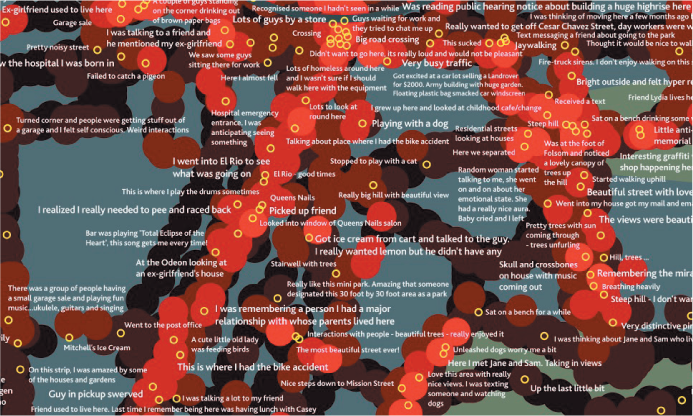

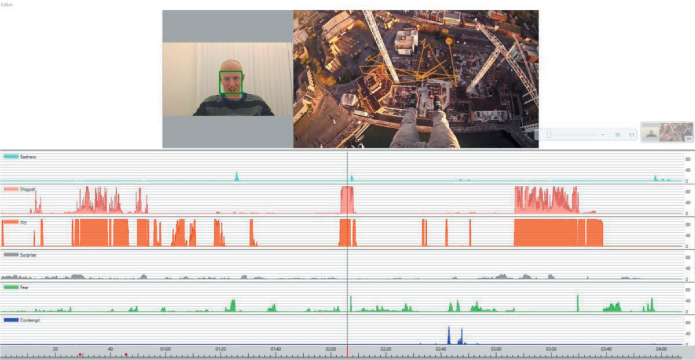

Emotion AI is no different in that respect; it’s observational, too. Already touted as a “lie detector,” it threatens to reveal your emotions, like it or not. Just as polygraphs tracked blood pressure and breathing to gauge stress levels associated with lying, so too does emotion AI. The emotion AI company Human promises real-time lie detection by analyzing faces from smartphone videos and security cameras (Figure 3-4). Coverus claims the same from eye tracking. Usually, the claim is not overt, but the assumptions are the same—smart observation reveals human truth.

Emotion AI is subject to many of the same pitfalls as any observational approach when it comes to the emotional side of experience. It captures physical signals that can be interpreted in many ways. It privileges the social performance of emotion. And it works within a limited context.

A vast expanse of human experience—arguably the most important part—is simply not considered by relying on what can be observed. Observation stays at the surface, so we miss out on how people perceive and interpret and feel. It omits how people make sense of their own experience. It skims over how people make their own meaning.

Figure 3-4. Can observation reveal our secrets? (source: Human)

The implications go beyond that. By privileging observation to such an extent, we privilege our own voice as designers and developers. We frame the story by choosing the context for observation. We get to tell the story, rather than giving people ways to tell their own story. We then shape the story going forward, based on our interpretation of what we can see.

So, we need to let emotion into research. And we need to work with mixed methods to understand all aspects of emotion. Design has already embraced mixed methods for research. Adding emotion just takes it a bit further.

Start by considering how to understand different dimensions of emotion. Emotions have a physical dimension. Maybe your face heats up or you feel a tightness in your jaw. Maybe you get butterflies in your stomach. Or, you know, maybe you just smile. Then, there’s also a perceptual dimension; how we recognize and interpret a feeling, what we call it, how we describe it, and what we compare it to. Our perceptions are grounded in memories and possibly in future projections, too. Some of our social response seems automatic; most of it is learned and highly context-dependent. There’s a behavioral dimension. You might yell in anger or frustration—an external behavior. But you could also suppress it or internalize it in another way. Emotional responses change depending on whether you are alone or with others. That’s the social dimension. And the unspoken norms, conventions, rules, and even stereotypes add a cultural dimension.

With so much to consider, we need to push mixed methods a little further. For now, some of the methods listed in Table 3-1 are fringe. Not every team has access to emotion-sensing devices and platforms, but you don’t really need to. Consider this collection of methods as a frame to build on as affective computing becomes more common.

| AFFECTIVE LAYER | SIGNALS | QUANTITATIVE METHOD | QUALITATIVE METHOD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurophysical | Pulse and temperature, gaze, brainwaves | Wearables, eye tracking, brainwave trackers | Observational research |

| Perceptual | Core affect, personal meaning | Data over time, aggregate data | In-depth interviews, diaries, metaphor elicitation, therapeutic research |

| Behavioral | Interactions | Behavioral analytics, satisfaction ratings | Observational research |

| Social | Facial expression, intonation, body language, language | Facial analysis, voice analysis, gesture analysis, sentiment analysis | Group conversations, paired interviews, co-design activities |

| Cultural | Norms, attitudes, laws, institutions | Location tracking, behavioral analytics, aggregate data, literature scans | Contextual inquiry, narrative study, co-design activities |

That’s big picture. Now let’s go step by step, starting with the most basic emotions. Even in broad strokes, even with the latest emotion AI, it’s not easy to do.

IDENTIFY BASIC EMOTION

Perhaps you’ve seen Pixar’s Inside Out? The movie is about five basic emotions: joy, anger, fear, disgust, and sadness. Although the filmmakers considered including a full array of emotions, they kept it to five to simplify the story. Whether you agree that these five are universals or not, these are simply big categories to use as starting points. Think of each as a continent. Within each there are many states, cities, disputed territories, shifting boundaries. Those we’ll fill in later through qualitative research. Most designers aren’t paying much attention to even these big categories in research yet, but there are three main ways to get started.

First, you can add some emotion awareness to what you already do. We already gather some information about how an individual frames an experience, how they interpret what they see, and how they take action in the context of usability tests. We already observe personal context and daily ritual or routine in ethnographic interviews. An easy place to start is to simply make a point to notice verbal cues, facial expressions, pauses or hesitations, and body language and gesture. In Tragic Design: The Impact of Bad Product Design and How to Fix It (O’Reilly, 2017), Jonathan Shariat and Cynthia Savard-Saucier share a list to notice, including sighing, laughing, shifting in a chair, nervous tapping, and forceful typing. Going back to our new rules of engagement, you’ll need to be aware of your own biases and expand your emotional vocabulary to make this work.

It’s easy enough to add emotion categories to your data collection sheets or logs. If you are running research sessions alone, you can take notes on a simple cheat sheet during the conversation if it’s not too intrusive or after the session when you review the recording. If you have a partner, they should record their notes, too. The more people you can factor in to record and interpret, the better.

A simple sort of happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise is a good place to start, even though it will be imperfect. You can take it a step further, analyzing the words in your written transcript using sentiment analysis or the tone in a voice recording using a tool like Beyond Verbal’s Moodies app. In workshops, I’ve had people try using Affdex Me and Moodies in combination to get a general read on emotion.

Obviously, there isn’t a one-to-one mapping between observed actions and emotion. A pause might indicate hesitation, confusion, or interest. Context might give you a clue, or it might not. Quickly swiping through might mean someone is having fun, but it could signal boredom or even anxiety.

Second, whenever possible, give people a chance to comment on their emotional experience. Add a way for people to self-report their emotion whether in-person or online. Even if you consider yourself keenly emotionally intelligent, you’ll miss a lot of emotional cues and you’ll misinterpret. Outward expression of emotion varies with social context, and research is an unusual one. People vary in their range of expression and intensity of emotion in ways you won’t be able to observe.

You can ask directly. Net Promoter Score or satisfaction surveys don’t tell us much about emotion. Instead, include questions that give people a chance to express emotion. A simple selection of smile or frown, thumbs up or thumbs down, can lend a basic read to positive or negative emotion. That’s a level one emotion signal.

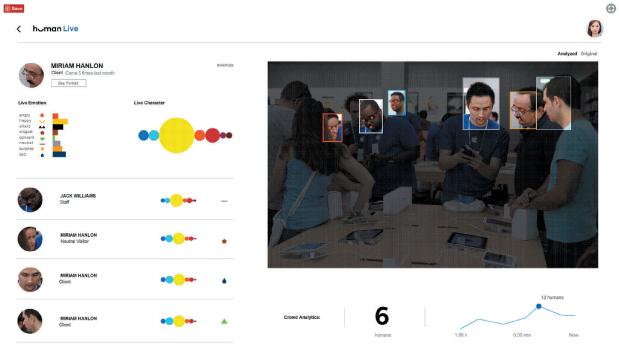

Better still to get a simple range of emotion. YouX (Figure 3-5) is an experimental tool inspired by Plutchik’s wheel of emotion.5 Tools like PrEmo, which rely on images rather than words, work around language barriers. It can get at multiple emotions at the same time and it translates across cultures better, but it still assumes that everyone will be able to interpret facial expression. Follow either approach with a narrative question though and you’ll get context to understand the emotion as well as more granularity. Layer in sentiment analysis on open ends, and you’ll get a general read on emotion.

Figure 3-5. Asking, with feeling (source: YouX Tools)

In a follow-up questionnaire or online survey, the most well-rounded approach is to give people a short list of emotions along with a narrative prompt to accompany it. In person, direct questions might not be the best approach. People are not apt to honestly reveal emotion to strangers in a research context. So indirect is best, whether you are prompting conversations between participants or engaging them in design activities.

Third, cautiously consider a tech layer. Emotion AI is able to detect broad categories, 5 to 10 at least. In the near future, it might be embedded in a product you’re developing, and you’ll be tasked with interpreting those signals to further evolve it. For now, it’s probably not. So, one way to get familiar is to begin trying some of the tools. You can certainly capture these same signals using existing research tools. A multimodal platform like iMotions layers together a few different biometrics tools to record facial expressions and tone of voice or heart rate (Figure 3-6). Getting participants in a lab, wearing headgear and sensor bracelets, is not the kind of research we typically do on design teams. Even so, trying it out can lend some understanding to how emotion detection embedded in products might work.

Figure 3-6. Peeling back the layers of emotion (source: iMotions)

Platforms that detect emotion don’t automatically interpret the results, revealing what it all means. Emotion AI embedded in a product won’t either. Instead it will begin mapping broad categories to anticipated behaviors and types of content. Think back to one of our core principles: don’t assume too much.

Now that you’ve started to tune in to emotion signals, you’ve got an initial read on in-the-moment reactions to a product or service. That’s still limited. Next, move beyond broad strokes to understand emotion with greater nuance, and over time.

ADD NUANCE AND TEXTURE

When you heard about Cambridge Analytica, were you mad? Or were you morally outraged, bitterly disappointed, filled with dread? Was the feeling intense? Did it linger? Did you comment online using words like “angry” or “bad,” or did you employ more nuanced words like “flagrant violation”? The more finely tuned your feelings, the more adept you’ll be at navigating your emotions.

The greater your sense of granularity and complexity, the richer your experience of the world, too. You’ll see analogies to wine or perfume. Think of it like fonts. Designers perceive subtle variations in the curvature of a’s and j’s, the slant terminal, or the spines. People who have less experience might not see these differences but can still distinguish between an oblique and an italic. A novice might be less capable of making these distinctions, perhaps picking out only differences between a serif and a sans serif. Then, there are those who have little sensitivity to fonts at all, just seeing letters in a string on a screen. Those novices won’t be equipped to decipher the subtle messaging behind a font choice or to select a font that perfectly conveys a feeling. Novices and experts alike can continue to learn and develop that intelligence. Ultimately, the payoff for discerning nuances in fonts is not as great as for emotion, but you get the idea.

If you’re able to make fine distinctions between many emotions, you’ll be better able to tailor them to your needs. You’ll adapt to new situations. You’ll be better at anticipating emotion in others. You’ll be able to read the emotion of a group. You’ll be able to construct more meaning from other people’s actions, too. A finer sensitivity to nuance translates to higher emotional intelligence. So, let’s see if we can bring that into design.

Emotion classification can be more art than science, with myriad possibilities. A few basic models can build toward greater nuance:

-

The circumplex model suggests that there are two main dimensions.

-

The PANA model, or positive and negative activation model, develops granularity along lines of positive and negative affect.

-

The mixed model, also known as Plutchik’s model, is a hybrid of circumplex for intensity (or arousal) and valence (positive or negative) (Figure 3-7).

Figure 3-7. A mixed model for mixed methods (source: Robert Plutchik)

Of course, it doesn’t end there. The PAD model adds dominance submission to the other dimensions of the circumplex model. The Lovheim cube of emotion is a three-dimensional model combining dopamine, adrenaline, and serotonin with eight basic emotions.

Rather than stress over which model to choose, the key takeaway is to understand a range of emotion. If the most emotionally resonant and sustainable relationships are the most complex, we need to lean into that complexity. Here are a few activities to add to your repertoire that will tease out more detail.

- Icon (or screen) annotation

- Studies tell us that icons can trigger feelings, but we’ve probably intuited that all along. Icons have symbolic value. That is, icons often begin to represent a feeling, a value, a person, an action, or a story. A quick exercise I use is to have people sketch or take a screenshot of their home screen or desktop and annotate each icon. You can ask for emotions or values—people often don’t distinguish between the two anyway—by prompting them to tell you what each means to them or what role it plays in their lives. Whether you are trying to understand your own app, or an analogous one, or how it might live among the others on a smartphone, this activity can help uncover deeper meaning and even how it shifts over time.

- Feeling drawings

- Rather than annotating icons or pages or photos with feelings, here you take the reverse approach. Instead, you ask people to draw what an experience feels like. The idea is to have people focus on illustrating their feelings rather than talking about them. Whatever the result, follow up with questions about what they drew and why. You can continue with more drawings too.

- Movie making

- Movies tap into emotion in a way that is profound and meaningful, but also indirect. Part of this is pure storytelling. Narrative is the superglue that helps us make sense of our lives. Part of this is also the way movies move us through time. In my own research, this translated to having people frame crucial moments with a device or app as a movie and then going back to “watch” these stories, noting the sequence, hitting pause on certain key events, muting the conversation to focus only on actions, fast-forwarding to look at consequences, and finally putting together a trailer to summarize.

- Object interviews

-

Made in cooperation with cultural institutions around the world, the object interview series, imagining objects as if they had separate lives, is quite whimsical. What if a vase were teaching French or a bench were playing hide and seek? As our tech products develop more personality and agency, this technique seems more and more relevant. If we consider people and product to be in a relationship, it means lending a voice to both.

Start with a narrative approach in which people tell stories about the product or an analogous product. If possible, start with one that elicits strong feelings (or even use that as a recruiting factor). Have them tell a story about it, show pictures, and draw it to describe that emotion. Then, flip it. Narrate from the object’s point of view. You’ll get a sense of how emotion builds or dissipates. You’ll begin to understand how conversations or interactions support or challenge.

- Kansei clustering

-

Kansei engineering, the Japanese technique to translate feelings into product design, has always seemed intriguing and a bit mysterious. Developed in the 1970s to understand the emotions associated with a product domain, the approach centers on an analysis of the “semantic space” gathered from ads, articles, reviews, manuals, and customer stories. The analysis can be large-scale and statistical, but it doesn’t need to be.

In my work, I begin with interview transcripts, diaries, customer stories, and social media posts, but I find just culling emotion words is not very helpful. Love, hate, like, distracted, and angry don’t mean much without the context. So, instead, bring it into a follow-up interview or a participatory design activity to fill in that missing piece.

- Worry tree

- Another technique that I’ve tried is using a worry tree. A little like the “five whys,” this technique looks at your anxiety or worry and traces it back to what you can do. You start with an anxiety. Perhaps it’s an anxiety caused by an existing technology, like FOMO. Or, perhaps it’s an anxiety that your technology is trying to address. After you list the anxiety, the next step in the tree is to list what you could do. If you can do something, you can begin to list how and when. If you can do nothing, well, then you need to let it go.

- Sentence completion

-

Sentence completion is a way to understand emotions and, in turn, values. Suppose that we are looking at a fitness app. You might include some sentences to get at emotions related to fitness, exercise, and healthy lifestyle. Here are just a few examples:

-

I feel ___________ when I exercise/eat healthy.

-

When something gets in the way of my routine, I feel ___________.

-

The best fitness experience is ___________.

-

When I think of my fitness/health, I dream about ___________.

You might also include exercises that ask about the app directly but emotion indirectly.

-

Using [app] is ___________.

-

To me [app] means ___________.

-

The [app] makes me think of ___________.

-

When I use [app], I think of myself as ___________.

-

When I use [app], other people think ___________.

-

Moving beyond basic emotion doesn’t need to be awkward or arduous. We can understand emotion by building on some of the techniques we already use or adding new activities and exercises to our repertoire. At this point, all of this emotional data is still abstract, though. Next, we need to visualize.

MATERIALIZE EMOTION

The finale to the find phase is to materialize emotion. Using technology, where appropriate, or low-tech prototyping methods, the aim is to find new ways to give substance to emotion uncovered in research. Creating a material vision surfaces the meaningful aspects of the experience.

Think of it as a remix of art therapy and participatory design research. Working within the comfort level of individuals and the team, the goal is to make the experience palpable. Making the data physical facilitates further discussion, and ultimately informs the design.

Organizations are already trying this approach in the mental health space. Mindapples provides kits for groups to share their “five-a-day” prescription for mental health. Aloebud is a self-care app that visualizes mental health as a garden. Stanford’s Ritual Design Lab installed a Zen Door in downtown San Francisco for the April 2015 Market Street Prototype Festival encouraging people to contribute their wishes as a kind of data sculpture.

Individuals are turning to it as a way of understanding physical and mental illness. For instance, Kaki King and Giorgia Lupi created data visualization to record a history of strange symptoms—mysterious bruises on Kaki’s daughter. The idea was not only to help understand the patterns but also to see with fresh eyes something that’s difficult to assess. At the same time, it became a coping strategy for processing the illness of a loved one. Laurie Frick’s Stress Inventory is another vivid example of transforming data she tracked about herself in a tangible form. It’s a way to interpret the data and a way to process the emotional impact.

When I run these sessions for clients, we distribute cards with a high-level activity related to building emotional capacity: discover, understand, cope, process, manage, enhance, remember, and anticipate. Depending on the project, there might also be cards that include scenarios or people, too. Most crucially, we create cards that summarize aspects of the data, such as a distribution of emotions words, a core emotion and related emotions, data that connects emotion with values, and so on. Each data card includes the topic, the source, a description, and a visual. Finally, I select materials that cover a range of properties. Materials that lend color like food coloring or paint. Materials like wood blocks that don’t have any give and, by way of contrast, materials that are flexible like moldable soap or erasers. Materials that bind together like elastic bands, or attract like magnets, or fit together like LEGOs. The idea is to represent a wide-open field of possibilities.

After an introduction to the activity and the data, individuals or groups choose and discuss the cards. Then, I have participants select a maximum of three materials before moving on to create a material representation of the research data and document their process. In a recent session about e-sports, emotion research materialized variously as a paper chain of people holding hands framed by color-coded translucent windows. It demonstrated how people were coming together for a certain amount of time to share an experience, that would color their view of reality afterward. This illuminated some of the emotional goals for the project while giving us a touchstone for further discussion.

The outcome is to find ways of characterizing and framing emotion, propose new ways of doing things or approaching issues, and gauge people’s reactions and responses. Rather than finding a universal color for joy or the default texture for security, which is likely a futile effort anyway, this instead lets us begin connecting physical qualities, features, and functionality with emotional experience. These emotional objects provide a bridge to the next phase.

Envision Experience

Now that we’ve collected more information about emotion, by documenting the emotions and values at play, we can try to shape this into a strategic direction. Because our emotional life is subject to so much variation, we need to begin by bringing more people into the process.

When we start to treat people as collaborators, we need to make sure that they have a way to contribute in a meaningful way. Our current repertoire of participatory techniques favors extroverts and, like any group activity, tends to privilege some voices over others. It’s on us to acknowledge and amplify unique voices. We need time to reflect and to respond critically. We should do everything possible to draw out the imagination of the broader community.

FOSTERING FRESH IDEATION

Ideation sessions, hackathons, design sprints, and co-designs aren’t always conducive to open conversation and thoughtful reflection on our inner lives. So perhaps our practices are due for a refresh. One way we can do this is to lend the right prompts, constraints, and opportunities to speak to their unique strengths and capabilities. Here are a few new ways to stretch our practice with a mix of social and less-social activities.

- Create intimate experiences

- To build communal spirit and encourage associative conversation, think about how to build codesign experiences that create a sense of intimacy. Rather than a conference room, even a hip one with glass walls and fun furniture, create a safe space where people can be a little vulnerable and power dynamics are leveled. The trend toward dinner parties like Death Over Dinner (Figure 3-8) or The People’s Supper is one that has promise for codesign. Alice Julier, author of Eating Together: Food, Friendship and Inequality (University of Illinois Press, 2013) finds, “When people invite friends, neighbors, or family members to share meals, social inequalities involving race, economics, and gender reveal themselves in interesting ways.” Some agencies, like Frog Design, are following suit with ideation sessions that take a more personal approach, held in homes or at off-the-beaten-path restaurants.

Figure 3-8. The best things happen over dinner (source: Death Over Dinner)

- Seek renewed inspiration

- Technology is not the first field to reinvent, however inadvertently, inner life. Philosophers and filmmakers, artists and architects, painters and poets have long contemplated our emotional world. In a series of pop-up events around the world called Future Feeling Labs, I’ve been doing the same. Each session elaborates on an emotion, like schadenfreude or outrage. We begin with a history through art, literature, and culture before moving on the current culture. Looking toward novelists as we characterize chatbots, or to sculpture as we create new objects, holds promise as intentional inspirations.

- Simulate emotional experience

- Sometimes, simulated experience can inspire and mobilize. An empathy museum that encourages patrons to try on the shoes of migrants and refugees while listening to their stories can transport you. Empathy kits, complete with augmented reality (AR) headsets and awkwardly shaped lollipops, can be a bridge to understanding autism or dementia (Figure 3-9). Typefaces that simulate the problems faced by people with dyslexia can prompt temporary attunement. Simulated experience gets us only so far. Empathy, emotionally attuned and cognitively aligned, will never be lived experience but it can lend emotional force to abstract problems.

Figure 3-9. A tidy kit unfolds into messy emotion (source: Heeju Kim)

- Strive for immersion

- Let the ideation session become a playing field for exploring different worlds. Virtual reality (VR) certainly has the potential to immerse us in other worlds and introduce multiple realities. But we don’t need VR for that. Think of language immersion programs, in which you leave your language and culture behind to enter a new world. Although we probably can’t make that drastic of a switch, we can cultivate that feeling that you have entered a new world. It could be a shared ritual that leaves behind the “old world” like when people turn in their smartphones as they check in to Camp Grounded. It could mean staying “in character,” like you would in a Live Action Role Play (LARP). Anything that brings an element of absorption to the session.

- Activate the senses

- Sketching and whiteboards are the typical tools for ideation. Unexpected materials seem to foster new pathways for creative thinking. Just as we habituate to what once made us happy, we also feel less than inspired by the usual supplies. At the University of Washington’s HCI design lab, pom-poms, pipe cleaners, and popsicle sticks nest in bins alongside sharpies and Post-its. Alastair Somerville’s popular sensory design workshops incorporate scent jars and walking tours. Many teams are experimenting with LEGOs and clay. My favorite supplies come from hardware store bins and fabric shops. Broken toys, party favors, and miniatures can also trigger unexpected creative collisions. The odder the objects, the more people open up.

- Add think-alone time

- Unstructured time and independent activities leave space for new ideas and critical thinking. Future Partners, for instance, makes silent walks an integral part of the ideation process. Even in a typical conference-room-with-whiteboards-and-Post-its ideation session, we can build in time for quiet. We certainly should include ways for people to be alone with their thoughts and then come together again as a group.

- Expand participation

- Think beyond everyone together in the same room. Why not invite people from anywhere to participate on Twitter or Snapchat? How about leaving a tabbed flyer with a number to call and leave a good old-fashioned voicemail? Future visioning agencies Situation Lab and Extrapolation Factory have invited anyone interested to call a toll-free number and record their future dream in a voicemail, using that as a foundation toward speculative design. Anything to challenge creative expression while involving more people.

It might sound like we are bringing empathy back into this phase. Yes. Empathy in all the phases. Besides a refresh on how we approach ideation, it has the potential to lend the support of disparate stakeholders. So, what do we do after we have a new frame for ideation? Create an emotional imprint.

IDENTIFYING THE EMOTIONAL IMPRINT

After you’ve developed a conducive co-design space, use the materialized research as a bridge to design. Begin with the mix of emotions associated with the experience. What is your product’s core emotion? What else is associated with that emotion? What emotion do you want to evoke? What emotions are people expressing? What emotions are unexpressed? Which are the most intense feelings people identify? Which are the least? When beginning, sinking into, and finally leaving your experience, what states are you evoking and in what order? Your research might have answered some of these questions; some might remain. Either way, we can use these answers to begin.

First, you’ll create a map of the emotions associated with the experience. Empathy maps connect feelings with thoughts and actions, but the tendency is still to “solve” negative emotions. Instead, let’s try to connect emotion with motivation.

Motivation has many models. There’s self-determination theory, focusing on competence relatedness, and autonomy. There’s ERG theory, comprising existence, relatedness, and growth. There are intrinsic and extrinsic theories of motivation. There are goal setting theories. But let’s start with the familiar.

In a co-design setting, start with Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs. Besides near-universal recognition, it lends itself to easily mapping emotion to motivations, values, needs, bigger goals. You can begin by drawing the pyramid with the five levels of needs: physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. When I do this exercise, I use the later model, which includes knowledge, beauty, and transcendence. To break out of hierarchical thinking, I don’t always use a pyramid (Maslow didn’t originally, either). It might be more difficult to consider those higher needs when basic physical and safety needs aren’t met, but every human life will still be shaped by higher needs, too. At scale, it’s dehumanizing to suggest otherwise. From there you can sort the emotional knowledge you gathered in research, according to needs, to see where strengths and weaknesses lie.

Sometimes, I use a four-world-style model, based on a pared-back model of emotional well-being (Figure 3-10). The matrix is a blend of Daniel Goleman’s model of emotional intelligence and recalls Patrick Jordan’s concept of the four pleasures. Emotional experience can be situated on a spectrum of self-directed or socially directed, pleasure-based or purpose-based, resulting in a four different kinds of experience.

-

Transformative, experience that facilitates personal growth

-

Compassionate, altruistic and prosocial experience

-

Perceptive, sensory-rich experience

-

Convivial, experience that brings people together socially

Figure 3-10. Four types of experiences to support emotional well-being

Transformative experiences create a context for an individual to grow and find personal significance. These are experiences promising to help you make progress toward a goal, whether it’s getting fit, saving money, or becoming more productive. Experiences that help you understand your psyche or your health go in this category, too.

- Emotions

- Curiosity, interest, anticipation, vigilance, pensiveness, pride, confidence, inspiration, fascination

- Values

-

Love of learning, achievement, wisdom, judgment, accomplishment, independence, capability, self-control, intellect, perseverance, prudence, self-respect

Examples: Duolingo, Fitbit, Lynda, Headspace, Mint

Compassionate experiences are those experiences that center on shared purpose, mutual growth, a common cause. Compassionate experiences facilitate giving, helping, and fostering empathetic community, from charitable giving sites to games for good, to civic action.

- Emotions

- Acceptance, trust, caring, kindness, sympathy, empathy, respect, consideration, hope, altruism, courage, compassion (counter to contempt, pity, indignation, hostility)

- Values

-

Fairness, perspective, community, equality, forgiveness, helpfulness, tolerance, citizenship, open-mindedness, integrity, mercy

Examples: Re-Mission, GoFundMe, Resistbot, Be My Eyes, WeFarm

Convivial experiences are social in the way that we most often think about social. These are experiences that emphasize bonding, reputation, shared activities, and conversation. Successful convivial experiences support layered communication, social experiences that engage the senses, mixed reality, shared rituals, and storytelling tools.

- Emotions

- Love, admiration, lust, desire, amusement, relaxation (counter to loneliness, shame, jealousy, social anxiety, isolation)

- Values

-

Friendship, social recognition, harmony, humor, intimacy, trust, nurturing, vulnerability, fairness

Examples: Snapchat, Kickstarter, Pokemon Go, Google Photos, Twitch

Perceptive experiences are sensory-rich with opportunities to play. They can be pure in-the-moment fun, like games or music, but can also help us to savor or wonder.

- Emotions

- Amazement, surprise, arousal, tenderness, playfulness, fascination, excitement, amusement, relaxation, relief (counter to confusion, bewilderment, boredom)

- Values

-

Humor, creativity, zest, curiosity, imagination, cheer, appreciation of beauty, comfort

Examples: Spotify, Monument Valley, Pinterest, Dark Sky, Keezy

Most products are not just one type, of course. An app for good like Charity Miles is both transformative and compassionate. Prompt, a visual diary for those who have memory loss, is both transformative and convivial. Wayfindr might be considered transformative but also perceptive. Skype could be convivial or compassionate, depending on how you use it. The point is not to fit an experience into a tidy box. Instead, it’s simply a way to analyze insights and understand strengths.

Let’s use Spotify to demonstrate how this works. Listening to music seems to sit squarely in the perceptive quadrant. If you think about making and sharing playlists, well, that is convivial. Perhaps you use Spotify Running to motivate you toward fitness goals. That’s transformative. We could easily imagine a Charity Channel or games that work with Spotify to raise awareness of social issues. That would be compassionate.

Ideally, you might try to boost all four quadrants. In practice, this is not always practical or even possible. But we can use the matrix to think through emotionally resonant experience in new ways and determine where to build capacity.

A part of mapping the emotional landscape means considering the emotional role the technology will play in people’s lives. Does it enhance an emotion that’s already there? Does it activate new emotion? Does it help people process their emotions about the product itself? Or relate to something else entirely? Does the whole experience stand in as a coping mechanism? Has it come to represent an emotional moment, or experience, or even just a feeling on its own? Recall Don Norman’s levels of cognitive processing: visceral, behavioral, reflective. Or, you can think about it in the following terms:

-

Source, the product itself elicits or inspires emotion.

-

Support, it helps people understand, process, cope, or otherwise handle emotions.

-

Symbol, the product or experience stands in for a feeling.

As a way to categorize qualitative research or as a way to define features and functionality, these three roles can serve as a guide. More often than not, a product will engage more than one of these core emotional roles. But even then, the emotional signature of each won’t necessarily be the same.

DRAWING APT ANALOGIES

You might say you feel empty to convey a lingering loneliness. Another day you may tell a friend that your outlook is sunny to communicate optimism for the future. Or maybe you feel like monkey mind is a good way to describe a persistent state of distraction. After a year of working through social anxiety, you might feel like a turtle poking its head out of a shell. Emotional states inspire little blips of poetry, in an otherwise prosaic existence.

When we try to articulate how we feel, emotion words—even an impressive vocabulary of emotion words—are not nearly sufficient. Instead, we fall back on metaphor. A metaphor is a pattern that connects two concepts. When we are considering emotions, it serves a double purpose: it articulates emotion and evokes experience. Metaphors bring the emotional imprint to life, giving us a rich set of concepts to work with as we design.

Analogy has long had an influence on design. Henry Ford’s assembly line was inspired by grain warehouses. Hospital emergency rooms draw from Formula 1 pit stop crews. Design thinking already relies on analogy to develop products. Yes, there is a difference between analogy and metaphor. Metaphor makes a comparison; analogy demonstrates shared characteristics. A metaphor sparks instant understanding, while an analogy often requires elaboration. For our purposes, let’s not get too down in the weeds.

So, here we’ll develop emotional analogies. This activity works best with a collection of emotion and value words. It’s fine to mix them because they will already be jumbled together. Shame surfaced because people felt they weren’t able to live up to expectations. Anxiety kept people coming back, increasing each time. Values like presence or generosity, for example, will likely be somehow connected with serenity and admiration. You’ve probably already stumbled across these connections in your research.

When you are working with metaphor, there are a few combinations that are most useful to inform design:

-

Emotion + attribute, for connecting emotion with physical aspects of experience like color, texture, scale, size, material, weight, temperature, luster, age, and depth

-

Motivation + interactions, for connecting social and emotional goals like belonging, transcendence, safety, flow, recognition, love, autonomy, and so on with how people will engage with the system

-

Value + natural world, for connecting values (or emotions) with the natural world like shadows, changing leaves, a flock of birds, roots, and so on

-

Behavior + relationship, for connecting an action or behavior with a relevant relationship metaphor like a friend, parent, physician, or pet

A metaphor-based approach bridges the abstract concepts around emotions, values, and motivations with concrete aspects of design like what the object might look like or what behaviors it supports. It nudges us toward new aesthetics and experiences and away from clichés, too.

TRACING A LONGER JOURNEY

Emotions rarely fall on a neat timeline. When we develop customer journeys, they seem tidy though. The narrative arc feels familiar. It begins with a negative emotion and builds to a positive moment. In reality, that’s rarely the case. A journey is alive with all kinds of emotion.

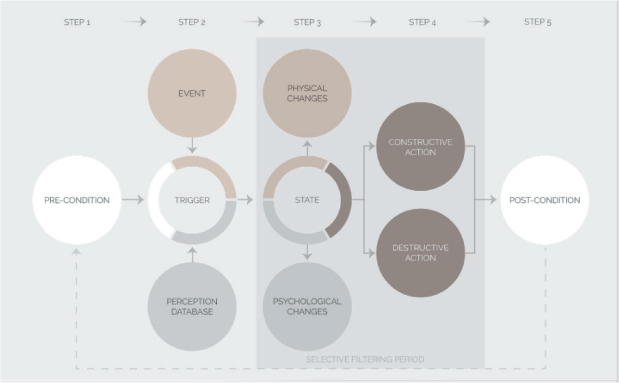

Most contemporary models of emotion include a few components (see Figure 3-11). It goes something like this:

-

Cognitive appraisal (evaluation of an event or object; let’s say a repeated misunderstanding by a voice assistant)

-

Bodily symptoms (rapid heartbeat)

-

Action tendencies (speaking more slowly or pounding your fist)

-

Expression (your face is twisted in anger)

-

Feelings (subjective experience of an emotional state, say terror)

Figure 3-11. An emotional timeline within a larger timeline (source: Atlas of Emotion)

Some would add your emotional state beforehand as a factor. Maybe you are already upset or you’re in a hurry, which could give some context to your response. Other experts would add your personality traits, and say you tend to be quick to anger. Maybe your mental health history is an issue; perhaps you have PTSD or have suffered some trauma. Most likely, you sift through a personal repertoire of memories as you process the emotion. You’ve had terrible experiences before, or you just read an upsetting story about a voice-assistant fail. Some of this new experience gets added to the mix; some doesn’t make the cut. To make matters more complicated, the next day, even though the voice assistant remains the same, you could have a totally different emotional experience. And then there’s the other people in your household…

Well, that got complicated. And it might well be something that machines are better able to map in the far-off future. For now, let’s dial it back a bit. Let’s think less about the event, or even a single experience. Instead, let’s look at the relationship.

Framing emotional design as a relationship hasn’t really taken hold, but it certainly isn’t new. In Design for Emotion (Morgan Kaufmann, 2012), Trevor von Gorp and Edie Adams drew connections between their ACT model (attract, converse, transact) and psychologist Robert Sternberg’s relationship phases: passion, intimacy, and commitment. Stephen Anderson, in Seductive Interaction Design (New Riders, 2011), modeled emotional experience on falling in love. We’ll revisit the relationship model again in Chapter 4 in the context of social bots. For now, let’s apply it to the overall experience.

Start with milestones. Every relationship has milestones, symbolic markers that form a kind of ongoing timeline. Perhaps you might think of big milestones, like moving in together or buying a home. It’s also small moments, like taking care of a partner when they’re sick or sharing a bathroom for the first time, or when you sent a text that only the two of you understood. Your relationship with a brand, product, or experience has these milestones, too. We already focus on firsts, like the first encounter, the first purchase, the first return. Consider other relationship milestones too, whether it’s introductions to friends or a deepening commitment.

Then, move on to meaningful moments. It seems obvious to start with emotional peaks and endings. Other moments may be even more important, though. Think about where there is a change in emotion or moments of strong emotion, good or bad. Those are the moments that reveal bigger values, build capacity, create support, form a memory. For example, Garren Engstrom of Intuit speaks about the moment of clicking “Transmit” using TurboTax software. Before that simple click happens, there are hours of mindless drudgery, intense effort, and a fair measure of anxiety. After you’ve successfully sent your return, you are likely to be flooded with emotion.

Finally, look at the emotional arc. After you have identified milestones and moments, you can begin to develop a narrative arc for each that draws on emotional experience. The first time you felt understood by a voice assistant might move from curiosity (“Can I ask this?”) to frustration (“How many times do I need to rephrase?”) to surprise (“Wait, that worked!”) to relief (“It feels like I can rely on it”) to bonding (“Wow, it really does understand me a bit better”).

As you move through these exercises, weight, texture, color, light, scale, and other aspects associated with the emotional experience will emerge. Some features will rise to the top, others fade away. Content and tone begin to align. For now, we have an initial plan for a more emotionally experience.

Evolve the Relationship

Developing emotionally intelligent design is grounded in deep human understanding. Rather than looking at experience as a snapshot, or even a progression, we need to shift toward considering how it evolves. It needs to be elastic enough to grow and adapt and change over time.

After you have a prototype, you should continue to do research. You should iterate, as one does. The most successful experiences find ways to evolve the relationship further though. If you’ve made it this far, you’ll have people who love your product or service. Paul Graham of Y Combinator once advised Airbnb to cultivate that crowd, saying, “It’s better to have 100 people that love you than a million people that just sort of like you.”6 Airbnb’s 100-lovers strategy meant engaging the most ardent fans to shape the community. Likewise, Strava evolved the experience with a small group of avid cyclists who helped it formulate an emotional profile for friendly competition. Strava’s team was able to translate the feeling of accomplishment and camaraderie to keep the community motivated.

The 100-lovers approach is one way to develop a bond. But it shouldn’t be the only way. The same dangers you might encounter with a panel or a small group of beta testers still apply. It can become an insiders’ club. It can be prone to tunnel vision. It can get tapped out. So, you’ll want to continually seek out new people. Consider adding people with mixed emotions or those who overcome negatives. Bright-spot analysis is a way to accomplish this.

In Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard (Crown Business, 2010), Chip and Dan Heath outline their process for finding bright spots. In every community or organization, there are people whose exceptional practices enable them to do better and feel more. These people might be considered the bright spots. For our purposes, it might mean studying how people adapt a negative experience in a positive way. It also might mean that they’ve developed a community, embraced a subculture, or adopted a set of behaviors that have shifted the experience.

As you’re evolving, you’ll be tempted to measure success, too. John and Julie Gottman have studied couples in their Love Lab at the University of Washington. Among other methods, the two rely on affective computing biometrics to monitor couple’s facial expressions, blood pressure, heart rate, and skin temperature, all while asking questions about how they met, positive memories, and moments of conflict. Micro-expressions, the Gottmans claim, reveal which marriages will thrive and which will fail. Based on this high-tech approach to relationships, John and Julie Gottman came up with a formula for a successful relationship: five positive interactions for every negative.

Almost in parallel, Barbara Frederickson came up with a 3:1 ratio for flourishing. That is, three positive emotions for one negative. Every so often, you’ll hear the idea of a magic ratio surface again.

A magic ratio turns out to be difficult to replicate. It’s easy to see why. Imagine a person who experiences three moments of joy in a day, another who experiences one moment of joy and two of contentment, and still another who experiences two of joy and one of anxiety. If we subtract negatives from the positives, it would seem the first two people are happier than the third. But emotions aren’t quite that mathematically predictable. The broader our range, the more resilient we become.

As appealing as the promise of a simple mathematical equation seems, our emotional life is more complicated than that. But here’s what seems to stick. Building capacity to grow, to change, to adapt, to make meaning matters more than tallies of positives and negatives. All that takes time, so as much as we try to actively evolve the experience, we also need to consider how people will live with it.

Live and Reflect

Much of our emotional lives can’t be understood at a sprint. We will get better at understanding emotion, creating a framework, and creating and testing designs to support it. But emotional experience is not static. Without a long view, we’ll lose the texture.

One way to keep growing is to look at ways to sustain the relationship. Usually, this means getting a fuller rendering of how people are making products a part of their lives. So, if we are looking for emotion resonance, we need to shift from the center to the edges. At the risk of overdoing the acronyms, I use DECIPHER as a shorthand. Here’s what it means:

- Dreams

- Wishes, hopes, dreams—we might shy away from these topics, unsure of how to proceed. Whether too personal, too aspirational, or just the firmly held belief that people don’t truly know what they want, we miss possibilities by avoiding. Yet, aspirations are where people create identity, and identity is the nexus of our inner emotional life.

- Etiquette

- We have shared conventions around behavior or expression, but often these are unspoken or even go unnoticed. Almost by accident, research can detect new etiquette (or lack of it)—phone stacking (already defunct), text speak, and ghosting are just a few examples. Etiquette contains clues about how we feel and what we value.

- Contradictions

- Another place to spend more attention is where we see conflicted feelings, behaviors, or use. For instance, parents who want to limit their kids’ time online yet still rely on devices to fill in gaps while they’re working would be a rich area of exploration. Often when we see contradictions between what people say and what they do, we choose to simply ignore the former. The truth is more complicated than that.

- Images and symbols

- Icons bring a rush of memories, feelings, and hopes. Apps can stand in for relationships. Wearables can signify membership. We attach to experiences where the experience itself might no longer be relevant. For instance, I regularly visit a forgotten Instagram of a friend who died years ago, like a pilgrimage. It feels like a little secret and I’ll be bitterly disappointed to find it deleted someday. Symbolic relationships often open up emotional memories.

- Peaks

- Our fondest memories and wishes are often mixed up with the technology. Yet, we might be celebrating the wrong things. Twitter will cheerfully tell us when we’ve hit a certain follower count, Headspace will let us know when we’ve reached a meditation goal in a super nonchill way, Facebook wants to celebrate every possible thing with us. We assume a lot. What do people consider peaks? What epiphanies do peak moments spark?

- Hacks

- As people make a technology their own, many develop workarounds, adaptations, and adjustments suited to their context and community. We get excited about these hacks but tend to happen upon them by accident, like the ACLU Dash button (Figure 3-12) to channel anger, or when they become popular, like IKEA hacks. Fixing strategies, creative repurposing, and unusual adaptations suggest ways to live successfully with technology.

Figure 3-12. Hacks creatively cope with mixed emotions (source: Nathan Pryor)

- Extremes

- People who push the boundaries to break new ground—the outliers—can guide us toward new possibilities. They might be theorizing new ways to build, experience, or replicate something that already exists or pursuing something entirely novel. It’s not just trendsetters who engage in extremes, it’s everyone at one time or another. It might be a social practice, a community, or a policy that is unusual but addresses a fundamental human need.

- Rituals

- Nervous tics, curious habits, repeated behaviors, cherished practices, and other ways people try to integrate technology into their daily routines can guide us toward emotional needs and deficits. When people try to train technology through repetitive actions to be what they want, we need to pay attention.

The DECIPHER model shifts attention toward the aspects of human experience that we miss, discount, or simply need yet to understand. Consider these the signals that will help us understand ongoing relationships, emotions, and values.

Emotional relationships with products in our lives change and grow in value over time. Maybe it’s a hand mirror, passed down for years, that once belonged to a great, great aunt. Perhaps it’s an old Beetle that you restore with VW Heritage parts. Maybe it’s a coffee cup with an interior pattern that develops with use (Figure 3-13).

For me, it’s the rocking chair gifted to me by my mother-in-law before my first daughter was born. A chair where I spent hours upon hours with each of my three daughters. Gazing down at their miraculous tiny fingers and breathing in that delicious baby head smell, crying from lack of sleep, pleading with my little darlings to go to bed. Later snuggling up to read Dragons Love Tacos and stabilizing the rocker with blocks for hideaways and tending to smushed toes. Laughing as my dogs tried to jump up, only to be deposited right back on the ground. Years later, the chair looks a mess, but there is no way I’ll be getting rid of it.

Our emotional relationships with technology, products, and our designed environment become more profound the more steeped they are in complex emotion. Delight enlivens, emotional extremes engage, emotional depth and complexity endures.

Figure 3-13. Emotional connection etched in coffee stains (source: Bethan Laura Wood)

Design Feeling Is the New Design Thinking

In the near future it seems a given that emotion will be designed into the experience. The text your phone sends you to say that your purchase won’t make you happy, the app on your phone that lets you tune in to your partner’s mood before they get home, the robot companion who senses your irritation and adjusts its tone—none can be automated. We will be called upon to design for a mess of human emotion and a range of outcomes. And that future requires developing a greater sensitivity to our emotional lives with technology.