Overview

- When does a cybersecurity incident become a crisis?

- When it impacts entire enterprise

- When it requires activation of disaster recovery plans

- For example, it becomes a crisis when a single compromised server becomes ten compromised servers, then a hundred, and pretty soon the entire data center is infected, damaged, or worse.

- Saudi Aramco in 2012: Shamoon virus infected ∼ 30,000 of its Windows-based machines.

- Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014: Malware stole huge amounts of confidential data.

- In addition, smaller incidents happen every day outside of the public eye.

- This chapter describes

- how things change when a crisis occurs;

- how enterprises behave under the duress of a crisis situation; and

- techniques for restoring IT during a crisis while simultaneously strengthening cybersecurity to protect against an active attacker who may hit the enterprise at any moment.

Topics

- Devastating Cyberattacks and “Falling Off the Cliff”

- Keeping Calm and Carrying On

- Managing the Recovery Process

- Recovering Cybersecurity and IT Capabilities

- Ending the Crisis

- Being Prepared for the Future

Devastating Cyberattacks and “Falling Off the Cliff”

Context

- A cybercrisis begins with a devastating cyberattack impacting an enterprise’s ability to function or deliver revenue-generating services.

- Stuxnet attack impairing Iranian nuclear program

- 2014 attack on a German foundry’s blast furnace resulting in extensive physical damage

- Many devastating cyberattacks involve attackers gaining complete administrative control of victim network.

- Unfortunately, many enterprises structure their security in a manner that attackers can gain administrative control relatively easily.

- Devastating cyberattacks and potential impacts can be characterized as follows:

- The Snowballing Incident

- Falling Off the Cliff

- Reporting to Senior Enterprise Leadership

- Calling for Help

The Snowballing Incident

- The true magnitude of a devastating cyberattack may not be visible initially.

- Cyberattack starts like any other incident.

- For example, an anti-virus alert or a logon fail with an administrator credential.

- As investigators analyze the incident and start correlating it across the enterprise, the incident’s impact expands.

- An administrator account is being used inappropriately throughout the enterprise.

- Malware is discovered on critical application servers, systems administration servers, or authentication servers.

- A piece of malware—once it is identified as such—is present on a significant portion of the enterprise’s computers.

- A large number of enterprise computers are communicating with an external command-and-control server.

- Once the right signatures are loaded into network security systems, the enterprise realizes malicious communications are taking place throughout the enterprise network.

- The snowball gets bigger and bigger …

Falling Off the Cliff

- As the investigation proceeds, the enterprise realizes this incident is

- not a small incident to be cleaned up in a day; and

- a “big deal.” (The enterprise is in “big trouble.”)

- Investigators refer to this situation as falling off the cliff.

- As the crisis snowballs, the enterprise’s ability to respond to it diminishes.

- The incident includes most, if not all, servers in the system, along with the consoles used to control them.

- Most computers are compromised.

- Most of the enterprise’s disaster recovery plans are not going to work because the attacker is in control.

- The enterprise is still uncertain as to what the attacker can or cannot do.

- The enterprise needs to be careful not to let the attacker in control know the enterprise

- knows what is going on; and

- is about to kick the attacker out.

- The attacker might react and do something extremely destructive.

- Cybersecurity staff should be cautious regarding their communications.

- Face-to-face and telephonic communications are preferred.

- Messaging, e-mail, and other collaboration tools can be compromised and tip off the attackers.

Reporting to Senior Enterprise Leadership

- As the enterprise understands the cyberattack’s magnitude, it is time to report the situation to senior leadership.

- Initial reports are most likely incorrect and do not accurately portray what it will take to resolve the situation.

- Report needs to present clearly the magnitude of the knowns, unknowns, threats, and risks.

- Key reporting points include

- what is known so far;

- what is not known so far;

- what is understood about the attacker;

- what will be required to stabilize the situation;

- what will be required to resolve the situation; and

- what help should be called in immediately to start the response.

Calling for Help

- Once senior enterprise leadership understands the magnitude of the cyberattack, leadership and employee channels will be consumed to

- keep organized around the situation; and

- maintain accurate status for leadership.

- Enterprises staffed for “normal” operations seldom have the bandwidth to handle additional reporting.

- Areas that may require help include the following:

- Strategy, Architecture, and Planning

- Advising leaders on the big picture for crisis

- Providing leaders with templates based on experience so leaders do not start from scratch

- Investigating the Incident

- Understanding the magnitude of the crisis, affected accounts, computers, networks, and malware

- Collecting information for remediation

- Strengthening Cybersecurity

- Reinforcing security capabilities so attackers will not be able to counterstrike while they are being removed or after remediation

- Rebuilding IT

- Reconstituting affected IT systems

- Restoring impacted business operations

- Tracking Status

- Keeping track of crisis activities

- Accurately reporting activities to leadership

- Facilitating discussions to understand and make risk-based decisions

- Trading off operational risk with cybersecurity risk

- Calling for help takes the pressure off regular employees so they remain focused on staying in control of the situation and making decisions.

Keeping Calm and Carrying On

Context

- As the magnitude of the crisis unfolds, people will be afraid for their

- jobs,

- careers, and

- livelihoods.

- Many people will look for mistakes that may have led to the situation becoming a crisis.

- It is critically important for leadership to keep calm and hold second-guessing in check.

- Everyone needs to stay focused on the problems and finding solutions.

This poster was developed in Great Britain as part of the preparation for World War II, but it was not widely distributed at the time.

The British government kept it in storage for use in case of a devastating German attack.

It was rediscovered in 2000 and has since become quite popular.

Playing Baseball in a Hailstorm

A

cyberattack crisis

is like playing a game of baseball while it is hailing baseballs.

- Keeping calm becomes more difficult as a crisis unfolds.

- Established communications channels become overloaded, along with corresponding leadership.

- Using the baseball analogy, everyone quickly becomes overwhelmed.

- Leaders spend most of their time in meetings.

- Leaders spend little of their time synthesizing reports, setting up assignments, or delegating tasks.

- Consequently, “the ball gets dropped” everywhere in the organization.

- Normal processes of reporting and delegating become ineffective.

- Usual communications channels of e-mails, voicemails, and meetings break down.

- In a crisis, the enterprise needs to change its method of operations (including support contractors) if it is to manage the crisis effectively.

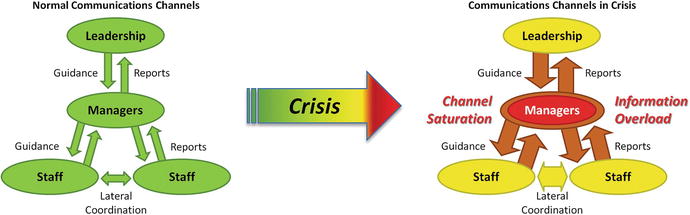

Communications Overload

- As the situation becomes a crisis,

- regular communications channels become saturated;

- managers become overloaded by status information, requests for support, and guidance from leadership; and

- communications overload seriously undermines the ability to accurately assess the situation.

- To improve the situation, staff and contractors can

- rely more on lateral communication to coordinate among themselves, which takes pressure off of managers who don’t have time for lateral communications.

- spend more time synthesizing their reports into formats that managers need rather than simply giving them raw data.

- elicit the guidance and requirements they need from managers rather than waiting for such information.

Decision-Making Under Stress

- As the crisis situation unfolds,

- confusion in reports and status information can have an extremely detrimental effect on management effectiveness;

- incomplete and inaccurate status can dramatically impede decision-making; and

- incomplete and inaccurate status can result in incomplete and inaccurate management guidance.

- Several factors contribute to difficult decision-making during a crisis.

- First, status reports are incomplete, do not contain the right data in the right format, or are not summarized in the right way for decision-makers to properly handle the data.

- Second, some status reports are inaccurate or get distorted as the reports get passed through multiple layers of management.

- Third, overwhelmed leadership misses important facts or performs inadequate analysis or synthesis of the facts, resulting in faulty decisions.

- To assist decision-makers in getting the best possible status and making the best decisions, remember the following factors:

- Accurate decision-making requires accurate data regarding the status, not opinions, about the status.

- Accurate Data = Four of five servers have been rebuilt and the fifth one will be ready tomorrow.

- Opinion = Most of the servers are done and the rest will be done soon.

- Opinions do not synthesize well into combined reports for key decision-makers.

- Accurate data or status information will not always be available and frequently decisions will have to be made with incomplete information.

- This situation is one of the most difficult situations for managers.

- Talented leaders can make “gut” choices in the absence of accurate data.

- Such choices will be revisited after the fact; that is, there will be an after-action review.

- Leaders need to capture and document their assumptions when making key decisions.

- Inaccurate status information is absolutely toxic to good decision-making.

- When different enterprise departments maintain their own status and the statuses do not match, senior leadership must spend valuable time de-conflicting the reports.

- Bad status can result in wasted time and delays in decision-making.

- Worst of all are decisions and guidance that are wrong due to inaccurate situational awareness.

Asks Vs. Needs: Eliciting Accurate Requirements and Guidance

- Staff and contractors should ask intelligent questions to help ensure the

- status they are giving is accurate and actually needed; and

- guidance they are receiving is actually the appropriate guidance.

- It is not unusual for staff members to send up a situation status report and expect certain guidance based on that status, only to get contrary guidance.

- This situation occurs because the original status was distorted going up the chain of command.

- It can also occur because the resulting guidance got distorted coming back down.

- Staff and contractors who recognize these disconnects can question the communications and address the distortions to help the enterprise make smart decisions.

- To help with clarification, staff and contractors need to following these recommendations:

- First, they need to have a conversation with management about what status management is looking for and what the resulting status actually means. In other words, what does management want to measure that accurately reflects the goal to be achieved and the corresponding progress toward the goal?

- Second, they need to have conversations with management when they receive guidance for action. They need to ask follow-up questions to understand better what management really wants (deliverables) to avoid wasting time doing the wrong thing.

- Third, they should elicit accurate deliverable requirements, particularly in contract situations where requirements are at the heart of the contract (for example, giving customer sample requirements to approve, disapprove, or correct to make it easier for management to provide concrete guidance). In other words, they need concrete guidance and get everyone on the same page.

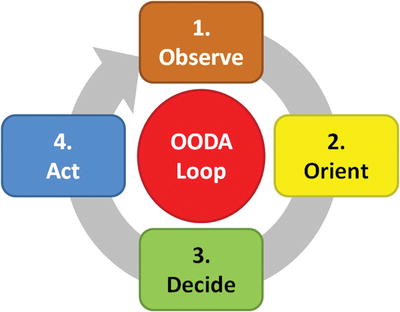

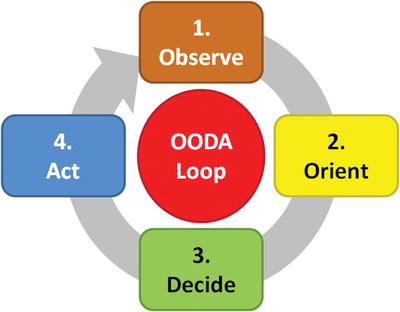

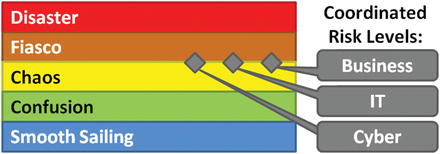

The Observe Orient Decide Act (OODA) Loop

- US Air Force Colonel John Boyd (1927–1997) developed the Observe Orient Decide Act (OODA) loop to describe how fighter pilots perform in combat.

- Enterprises can apply this model when they make decisions.

- The four steps are as follows:

- Observe: Collect status from personnel “on the ground” and synthesize the status into a coherent picture for decision-makers

- Orient: Analyze the situation and prepare to make the decision; may involve processing status data into “actionable intelligence” and preparing plans and alternative courses of actions for decision-makers

- Decide: decide on a course of action and break decisions down into their contingent parts so teams can take actions based on the decision

- Act: execute the decisions by repositioning resources and executing procedures (in other words turn the decision into actions, and observe the results and impacts … then cycle begins again)

- If an enterprise can operate faster than the cyberattacker’s OODA loop, then the cyberattacker will be forever “one step behind” and unable to respond effectively to the enterprise’s actions.

Establishing Operational Tempo

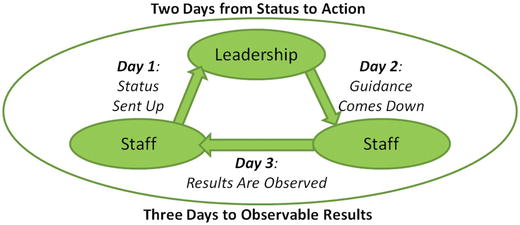

- The OODA theory maps directly to enterprise crisis operations.

- Information collection

- Decision-making

- The theory states that reports and decisions have to be synchronized so that there is time to observe the results of decisions before making new decisions to continue moving forward.

- Making decisions at an accelerated rate requires that reporting, meetings, and coordination all take place at an accelerated rate as well.

- This synchronization defines the enterprise’s operational tempo.

- The pace of decision-making depends on the time required for each OODA step.

- Operational changes can be made hourly by simply changing operational parameters.

- Staffing changes can take weeks to execute (hiring, training, and so on).

- Engineering changes can take days, weeks, months, or years (re-tooling, testing, and so forth).

- Strategy shifts can take months or years to observe and orient before making key decisions.

- In a crisis, faster OODA loops may be required (for instance, hours vs. days).

- Normal business operations often revolve around a weekly tempo of reports and decision-making.

- At low levels, there may be daily, or even hourly, “huddles” to make sure everyone is on the same page and problems are dealt with quickly.

- Staff and teams may meet weekly to coordinate.

- Strategic management layers may meet monthly, quarterly, or annually.

- Crisis business operations tend to be compressed due to urgency of the situation.

- Every hour is used to its maximum to make progress against threat.

- Crisis operational tempo tends to be daily.

- Even with daily reporting and guidance, there are delays and it can take several days for

- status to travel up the hierarchy;

- decisions to travel down the hierarchy; and

- the impacts of the decisions to be observed and reported back up.

- Traditional meetings often don’t keep pace with a crisis; the crisis requires alternative methods, procedures, and tools to co-locate observers, analysts, and decision-makers (for example, war rooms and crisis operations centers).

Operating in a Crisis Mode

- During a crisis , it is helpful for an enterprise to think about the following key crisis factors:

- Planning: It is important for an enterprise to have a crisis recovery plan.

- Process: An enterprise needs to establish a process for the recovery effort.

- Prioritization: The next challenge is to prioritize recovery efforts.

- Parallelism: An enterprise may have a lot of resources at its disposal.

- Sequencing: It helps to ensure recovery happens in the right order.

- Crisis Factor: Planning

- Does not need to be elaborate

- Needs to have some agreement on where to go and how to get there

- Establishes initial operating capability (IOC) and full operating capabilities (FOC) targets

- Needs to get everyone “on the same page” to help manage the chaos

- Can be refined and detailed as crisis unfolds so everyone gets required information

- Can occur “just in time” along with everything else in the recovery process

- Crisis Factor: Process

- Reduces ad hoc communications and enables teams to interface smoothly

- Should contain the following elements:

- Regularly scheduled meetings for reporting, coordination, and issue discussion

- Standardized formats for reports and requests

- Supporting capabilities such as telephone bridges, document repositories, request trackers, and workspaces

- A room where people can go to for information, a whiteboard containing important announcements, a telephone bridge, or a request line staffed by support personnel

- Crisis Factor: Prioritization Factor

- Tends to be difficult because everyone wants everything recovered immediately and IT systems that are nonfunctional have critical business consequences

- Lacks enough resources to do everything simultaneously

- Requires tough decisions

- Turns IT discussions about technical priorities and dependencies into discussions about business priorities so leadership can make informed decisions

- Crisis Factor: Parallelism Factor

- Organizes the resources so they are working at maximum efficiency

- Requires minimizing resources tripping over each other while waiting for interdependencies among teams and systems

- Plans recovery activities by keeping available resources fully utilized at all times, thereby avoiding time spent waiting on interdependencies

- Requires a delicate balance between parallelism and prioritization

- Crisis Factor: Sequencing Factor

- Avoids having critical resources sitting idle while they are waiting for other pieces of the enterprise to recover

- Builds IT system layers in correct order to deliver capabilities

- Networking, storage, computing, operating systems, applications, Internet connectivity, and clients

- Tests IT systems late in the recovery process due to the time required for all pieces to be integrated

- Establishes an initial operating capability (IOC) vs. full operating capabilities (FOC) so recovery can continue in parallel across multiple tracks

Managing the Recovery Process

Context

- The CIO looked around at his staff as the gravity of the situation sank in … the attackers had complete control, and the enterprise was entirely at their mercy.“So, what do we do now?”The CISO leaned forward and replied, “Now we fight!”

- What does an enterprise need to do in a cybersecurity crisis to regain control of the situation, rebuild impaired systems, and recover lost business functionality?

- Engaging in Cyber Hand-to-Hand Combat

- “Throwing Money at Problems”

- Identifying Resources and Resource Constraints

- Building a Resource-Driven Project Plan

- Maximizing Parallelism in Execution

- Taking Care of People

Engaging in Cyber Hand-to-Hand Combat

- The beginning of a cyberattack crisis is not the end of the cyberbattle, which generally consists of the following phases:

- Stealth: In the beginning, attackers often have stealth on their side as they move slowly and carefully to avoid setting off enterprise defenses.

- Discovery: After enterprise defenders discover the attack, they should move carefully to avoid tipping their hand and letting the attackers know the enterprise is aware of the attack. Defenders analyze the attack sequence to understand the extent of the attack and consider defensive and remediation options.

- Containment and Remediation: Now the game is on. Defenders attempt to contain the attack and remediate affected systems. Mistakes and oversights allow the attackers to retain their foothold or retake it after they are first repelled.

- Counterattack and Battle: After the initial remediation, attackers may attempt to regain control of the enterprise. Attackers now know the defenders are on to them, so they often switch tactics. Speed and tenacity are all-important now as the cyberbattle may wage back and forth for days, weeks, months, or even years.

- Entrenchment and Stabilization: Eventually, the situation stabilizes, with one party emerging victorious. Generally, defenders regain control of the enterprise. Sometimes, attackers outmaneuver the defense and disappear inside of unmonitored IT systems, thus retaining their foothold on an ongoing basis. Other times, the business disruption required for complete eradication may be too great and the attackers continue to have access to noncritical systems.

- For cybersecurity personnel in the midst of battle, it feels like cyber “hand-to-hand combat” as attackers take over accounts, computers, servers, and networks. The process is grueling and exhausting.

“Throwing Money at Problems”

- In a crisis, money may be the only lever an enterprise really has to deal with problems and take pressure off of overburdened staff and teams.

- Buy Experience: Bring in service providers to help with planning, investigation, cybersecurity improvements, IT rebuilding, and status tracking to free up employees so they can provide leadership and strategy

- Buy Services: Buy supplemental services while enterprise IT systems are offline during the recovery process

- Buy Capacity: Buy excess capacity on a temporary basis during the rebuilding process as some systems may be held as evidence for criminal investigations or to provide capacity to support parallel rebuilding

- Buy Capability: Negotiate with vendors for “sampler platter” licensing contracts that enable the enterprise to use the vendors’ full range of products, and to rapidly test and discard options without getting bogged down in contract and licensing negotiations; for the long term, only keep the capabilities that are ultimately needed

- Buy Contingencies—Hedge against potential failures and uncertainties during the rebuilding process to guard against big problems becoming showstoppers

- Money can be used to obtain expertise, services, software, and equipment to give the recovery effort options and flexibility.

Identifying Resources and Resource Constraints

- An early step in the recovery process is identifying the resources available for the recovery effort , which ones are going to be critical, and which ones are going to be overtaxed, such as

- Leadership and Project Management: Leadership and project management quickly become saturated in a crisis situation and need whatever useful relief they can get.

- Incident Response and Forensics: Few enterprises have in-house incident response teams that are staffed to handle an incident of any magnitude.

- Cybersecurity Engineering: Efforts to shore up cyberdefenses in the wake of a breach will likely exceed the capacity of the existing team; such expertise is critical for proceeding.

- IT Infrastructure and Backups: As rebuilding efforts get underway, critical infrastructure elements— such as networking, firewalls, storage, computing, and backup systems—become bottlenecks to progress and system recovery.

- IT Support and Help Desk: If major changes are performed to endpoints or enterprise applications, IT support staff quickly become overwhelmed in supporting impacted employees who are unable to work effectively.

- As these resource constraints are identified, planners can hedge against them by obtaining additional resources , lining up contingency resources, or exploring alternative approaches.

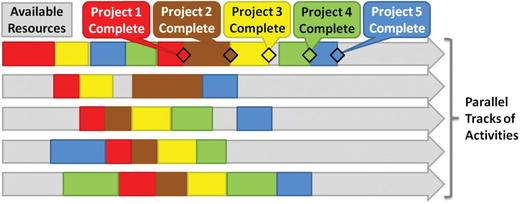

Building a Resource-Driven Project Plan

- The result of the recovery planning effort is a resource-driven project plan vs. a normal project plan.

- Resource-driven projects are designed around primary constraints—time and available resources.

- The goal is to ensure all resources are gainfully employed at their maximum level so the rebuilding process goes as quickly as possible.

- The highest-priority project should be overlaid onto the resources first—part of critical path.

- Lower-priority projects are sequenced later with the understanding that they will spend time waiting for the resources needed to execute successfully.

- High-priority, mid-priority, and low-priority projects are laid out and sequenced.

- Low-priority projects are worked on an “if-time-is-available” basis until higher priority efforts are completed.

- The graphic depicts how five projects can be overlaid onto available resources so the highest-priority project completes first.

- It also depicts the projects progressing linearly; the reality is much more complex and iterative.

- Projects can be performed out of sequence to compress overall project schedule, but risk goes up.

- “Keep calm and carry on” while remembering that in a crisis you never have the resources you need to do everything you want.

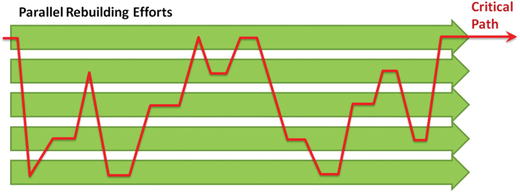

Maximizing Parallelism in Execution

- A resource-driven plan strives to optimize available resources to get the most important recovery activities completed first to help the business recover as quickly as possible.

- As the plan is executed, the critical path jumps around among the different teams as each team’s activities become critical to the rebuilding process.

- Teams that have resource constraints may be disproportionally represented on the critical path.

- Teams include leadership, incident response, cybersecurity, IT infrastructure, and IT support teams.

- In a highly parallelized rebuilding effort, the critical path can jump around among the different parallel tracks.

- A critical path analysis helps to identify risks so leadership can line up contingency plans or resources to keep risks manageable.

- Delays in recovery can cost thousands or even millions of dollars per day in lost productivity.

- Business leaders need to calculate the cost of lost productivity so that they can make smart investments to reduce the real or potential costs of such delays.

Taking Care of People

- During a crisis , there are periods where people dive in and give up their nights and weekends to deal with the crisis, but such efforts are difficult to sustain.

- Leadership needs to establish a sustainable pace for the overall effort (probably a marathon, not a sprint) that is in effect 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- Establishing a pace includes

- identifying key decision-makers (such as CIO and CISO) who do not need to be available 24/7, but who are available to make decisions at critical times;

- Getting personnel backups (for example, deputies and senior direct reports) so that key decision-makers can get the rest and breaks they need to be able to stay on top of things; and

- arranging shifts, relief schedules, and vacations.

- Management should watch out for the technical people who are consulted on every project or who are the sole source of institutional knowledge on key systems.

- When such technical people are identified, leadership should consider the following:

- First, ensuring these people are incentivized to stay through the recovery process

- Second, ensuring they have some relief by assigning colleagues or consultants to assist them

- Third, watching their work schedules and making sure they are given breaks when opportunities arise

- Leadership should establish work schedules to ensure everyone gets time off with some regularity.

- Leadership can support morale with inexpensive activities (for example, catered food) to help everyone stay productive.

Recovering Cybersecurity and IT Capabilities

Context

- As the recovery process gets moving, there will likely be two parallel tracks occurring.

- Remediation and strengthening the cybersecurity situation

- Restoration of damaged IT capabilities

- Cybersecurity improvements in controls (particularly preventive controls) can often interfere with the rapid rebuilding of compromised IT systems.

- Consequently, these two parallel tracks may be in tension with one another.

- How can an enterprise deal with this tension?

- Building the Bridge While You Cross It

- Preparing to Rebuild and Restore

- Closing Critical Cybersecurity Gaps

- Establishing Interim IT Capabilities

- Conducting Prioritized IT Recovery and Cybersecurity Improvements

- Establishing Full Operating Capabilities for IT and Cybersecurity

- Considering Cybersecurity Vs. IT Restoration

- Preparing for Maximum Allowable Risk

- Leadership must carefully manage this tension to ensure IT does not jeopardize the recovery process by undermining cybersecurity protections.

Building the Bridge While You Cross It

- “Building Airplanes in the Sky”1

- Construction workers build an airplane while it is in flight.

- Workers parachute off the completed airplane at the end.

- Analogy: Complex systems present building and deployment challenges, particularly when the systems are needed immediately or are operational throughout the project.

- “Building the bridge while you cross it” is a similar analogy for the relationship between cybersecurity and IT recovery during an extensive rebuilding effort.

- Cybersecurity needs to protect IT.

- Cybersecurity also relies on IT to provide the enterprise with networks, storage, and computing needed to deliver cybersecurity protective capabilities.

- If cybersecurity gets ahead of IT, it will deploy security capabilities that IT cannot use, thus getting in the way of the IT recovery process.

- If cybersecurity falls too far behind IT, the IT systems will be deployed without the cybersecurity protections the systems need to be safe.

- Cybersecurity needs to protect IT as systems are built, but cybersecurity also relies on those systems to support IT.

- Cybersecurity and IT efforts need to be carefully synchronized so that IT functionality and cybersecurity protection both come online together.

Preparing to Rebuild and Restore

- A balanced strategy for rebuilding considers the following questions:

- What will it take to disrupt the attackers?

- What will it take to deny the attackers the ability to operate in the IT environment?

- What will it take to regain cybersecurity control?

- What will it take to recover impaired business IT capabilities?

- What is the minimum amount of cybersecurity necessary before proceeding with the IT recovery process?

- How can cybersecurity enhancements be phased so cybersecurity and business recovery can proceed together?

- What if the attackers counterattack in the middle of the recovery process?

- What is at risk if cybersecurity gets defeated while the recovery is in progress?

- What is the business’s tolerance for risk in the overall recovery effort while balancing business impairment, IT recovery, and cybersecurity?

- Generally, the resulting plan should use a phased approach to start the recovery without making the situation worse.

- First, critical cybersecurity controls are shored up enough to remove attackers from the enterprise, or at least deny them administrative control.

- Second, interim IT capabilities are established so the business can continue functioning.

- Third, more extensive IT recovery is performed in parallel with more extensive cybersecurity improvements. These two tracks run in parallel, building the IT bridge while cybersecurity crosses it. This approach is used to establish initial operating capabilities for IT and cybersecurity functions in parallel.

- Fourth, as the situation stabilizes and the business regains functionality, initial operating capabilities are matured into full operating capabilities, with full capacity, high availability, redundancy, and disaster recovery as needed by the business.

- The strategy helps allow recovery while enabling the enterprise to proceed with an agreed-upon balance of business, IT, and cybersecurity risk.

Closing Critical Cybersecurity Gaps

- First recovery steps:

- Repel attackers actively inside the enterprise environment

- Close critical cybersecurity gaps so that attackers cannot interfere with recovery process

- It is not realistic to think cybersecurity can be immediately brought up to par.

- Small, incremental steps may be taken to deny attackers administrative control or keep them out of critical infrastructure.

- Use of air-gapped systems and networks

- Establishment of multi-factor authentication on critical system accounts

- Initial key actions to consider in the recovery process include the following:

- Disrupt attacker communications channels so attackers cannot control malware inside the enterprise that might be left over from before the attack

- Protect critical systems administrator accounts with multifactor authentication, rapidly changing passwords, or extensive auditing

- Protect critical security servers through patching, hardening, network isolation, or monitoring

- Isolate key infrastructure onto separate network segments with restrictive firewall rules

- Use application whitelisting or monitoring to detect unauthorized changes on key and/or vulnerable systems

- Establish 24/7 monitoring and altering to detect and respond to future attacker activity

Establishing Interim IT Capabilities

- While cybersecurity gaps are being closed, IT can simultaneously start preparing IT capabilities to replace lost capabilities and support the recovery process.

- Options depend, in part, on the severity of what was lost and the long-term IT strategy.

- Transition production IT data and services to development or staging systems that were unaffected by the attack

- Recover IT servers from backup and bring them back to operation as they were before the attack

- Recover IT data from backups and rebuild affected servers as they were before the attack

- Migrate IT functions to cloud services, either on a temporary or a permanent basis

- Accelerate otherwise planned upgrades to IT systems and roll out upgraded systems

- Use manual workarounds, such as pen and paper or personal computer tools, rather than enterprise applications

- Combinations of these approaches can work well.

- Don’t underestimate the value of manual workarounds that work fine on a temporary basis and free up critical IT talent to focus on recovering important IT systems.

Conducting Prioritized IT Recovery and Cybersecurity Improvements

- Once critical cybersecurity gaps are addressed and interim IT capabilities are established, the recovery effort begins in earnest.

- Prioritize activities based on business needs

- Break up recovery into multiple phases of IT capabilities so that initial operating capability (IOC) is delivered quickly and full operating capability (FOC) is delivered later

- Use limited resources to deliver the greatest amount of IT functionality in the least amount of time

- In parallel with the IT recovery, the enterprise will most likely make improvements to cybersecurity capabilities.

- Ensure recovered IT systems are adequately protected from current attackers or other more advanced attackers in the future

- Plan carefully so improvements don’t interfere with recovery activities

- Break up improvements into IOC and FOC phases to effectively use limited engineering, deployment, and support resources

Establishing Full Operating Capabilities for IT and Cybersecurity

- With the completion of IT recovery and cybersecurity upgrades, the IOC is established for the majority of functions damaged or loss due to the crisis.

- The enterprise should be able to resume normal operations as it was conducted before the crisis.

- Work remains to achieve FOC and remove limitations associated with capacity, redundancy, high availability, disaster recovery, or security.

- Schedule, budget, or resource constraints impact the FOC timeline, which can takes months or even years.

- Systems may operate in a “high-risk” configuration until required budget is available.

- While uncomfortable, decisions and trade-offs are appropriate to balance the business, IT, and cybersecurity risks involved.

Cybersecurity Versus IT Restoration

- Throughout the recovery process, there will likely be an active tension between cybersecurity and IT.

- Cybersecurity controls inevitably get in the way of IT personnel recovering systems and rebuilding IT capabilities.

- To maintain a balance between these recovery activities, it is important the enterprise embraces this tension and maintains open communications channels on what is working and what is not working.

- There is no one right answer—only a delicate balance.

- What actions can the enterprise take to maintain this balance?

- Educate IT staff on the purpose of cybersecurity controls that interfere with their work and let everyone know that management understands how the controls impact productivity

- Ensure cybersecurity staff understands the operational impact of cybersecurity controls and plans ahead for alternatives should this impact becomes untenable

- Have leadership regularly monitor the productivity impact of cybersecurity controls and be prepared to execute contingency plans if necessary

- Have cybersecurity be proactive about what they are doing and why

- IT staff will be more supportive , contribute to solutions, and come to their own conclusions that the chosen controls are the least adverse alternatives.

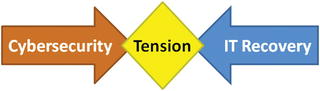

Maximum Allowable Risk

- Throughout the recovery process , business, IT, and cybersecurity leaders need to ensure all aspects of the recovery are performed at the same overall risk level.

- Depending on the severity of the original crisis, an enterprise’s tolerance for risk may vary.

- If the crisis was minor, the enterprise appetite for risk in the recovery may also be low.

- If the crisis was catastrophic, the enterprise appetite for risk in the recovery could be very high.

- Leadership should constantly monitor risk to ensure the risk levels stay as well coordinated as possible.

- The primary business driver is speed.

- Business leadership will likely push IT and cybersecurity to move at the maximum speed possible to get recovery done securely without resulting in spectacular failure.

- Business impairment may be worth thousands or millions of dollars a day.

- When such costs are high, the business appetite for risk in the name of speed will likely be quite high.

- Challenge is translating these risk factors into business decisions so that leaders can make the best-informed decisions possible.

Ending the Crisis

Context

- As the expression goes, “This too shall come to pass.”

- The enterprise eventually reaches a point where it is no longer operating in crisis.

- This transition generally happens at different times for different teams.

- Some personnel—particularly cybersecurity personnel—stay in crisis mode long after most employees have gotten back to business as usual.

- How does an enterprise deal with transitioning from crisis to “normal” operations?

- Resolving the Crisis

- Declaring the Crisis Remediated and Over

- After-Action Review and Lessons Learned

- Establishing a “New Normal” Culture

Resolving the Crisis

- Generally , a crisis winds down through four recovery phases as different parts of the enterprise return to normal operations :

- Regular Employees: The first phase occurs when basic enterprise functions are restored, often using interim or contingency capabilities. Interestingly, for most regular employees, this first milestone marks the conclusion of the crisis since the impact to their ability to do their jobs is largely mitigated.

- Corporate Staff: The second phase occurs when the most important enterprise IT systems are recovered to initial operating capability (IOC). At this point, business personnel (corporate staff) are able to get back to work using their normal processes.

- IT Staff: The third phase occurs when IT systems are fully restored back to full operating capability (FOC). At this point, IT staff can get back to a regular schedule of system maintenance, updates, and improvements.

- Cybersecurity Staff: The fourth phase occurs when cybersecurity improvements are completed and cybersecurity staff can “relax” and get back to their business as usual.

Declaring the Crisis Remediated and Over

- At some point during the four recovery phases, enterprise leadership is able to declare the crisis remediated and over.

- Why is it important to declare the crisis remediated and over?

- First, employees need to understand the crisis is over and the expectation for them to go the extra mile is no longer present. Employees can get back to a normal work-life balance, take care of families and households, and enjoy vacations.

- Second, there may be policies and procedures put in place specifically for the crisis that need to either be returned to normal or permanently adjusted into part of the new normal.

- Third, often crisis situations are funded and accounted for separately from normal business operations so they can be tracked as one-time events or may even be paid for separately by insurance. The costs associated with the crisis need to be accounted for and the end of those expenses must be clearly delineated.

- There is no hard-and-fast rule when the crisis is declared remediated and over, but generally it is some time between the third and fourth phases.

After-Action Review and Lessons Learned

- When the crisis is declared complete,

- leadership should get together and make a list of lessons learned—not a huge list, but a candid list of what went well and what went poorly; and

- lessons learned will help the enterprise handle the next crisis a little better

- lessons learned are important inputs into strategic culture shifts that will persist long after the original crisis is resolved, establishing a “new normal” culture

- The after-action review should include lessons in successes and failures regarding the following:

- Balancing of operations vs. cybersecurity and recovery

- Task organization and coordination

- Performance of technologies, procedures, and techniques

- Performance of teams and organizations

- Performance of partners and contractors

- Recovery costs and cost-savings opportunities

Establishing a “New Normal” Culture

- Every crisis has a lasting impact on an enterprise.

- The challenge is to leverage the crisis to

- make strategic adjustments to the enterprise culture, emphasizing computer and information security more greatly than in the past; and

- translate those cultural changes into a “new normal.”

- Concrete and visible changes include the following:

- Greater willingness among business leaders to trade-off cost and productivity in the name of cybersecurity

- Greater security of endpoint devices and computers at the expense of functionality

- Restrictions on the use of personal computing devices and conducting enterprise business from home or other locations

- Greater emphasis on using enterprise devices inside of controlled facilities to do critical work

- Greater discipline among IT staff to focus on protecting enterprise systems and servers

- Employee awareness training on cybersecurity concerns and potential threats

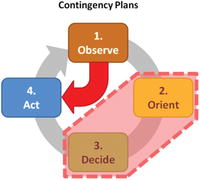

Being Prepared for the Future

“Disasters happen, and they happen to everyone … eventually.”

- Contingency planning reduces time in the “Orient” and “Decide” phases of the OODA loop.

- When contingency scenarios are well-defined ahead of time, staff can go straight from “Observe” to “Act”; this helps to minimize wasted time.

- Such planning is critically important for incident rapid response scenarios. Specific attack scenarios can be worked out ahead of time along with response procedures to isolate affected accounts, computers, networks, and servers so that attacks can be stopped before they get out of control.

- Disaster recovery resources reduces time in the “Decide” and “Act” phases of the OODA loop.

- When disaster recovery resources can be brought to fruition quickly in a future crisis, staff can go straight from “Orient” to “Observe”; this helps to determine if the resources have their intended effect.

- Resources may be offsite backups, contingency systems, or cloud services that are pre-coordinated and prepared ahead of time.

- Realistic training and tabletop exercises provide insight on how to operate in a crisis and what capabilities are needed.

Footnotes