CHAPTER 1: WHY DO ORGANISATIONS EXIST?

The fundamental question

A politically incorrect answer to this question would be that organisations exist to allow individuals to make money (in the private sector), or to wield power (in the public sector). After all, in the case of the former, the world economy is dependent on businesses making capital and creating wealth and, in the case of the latter, whether democratically elected, or simply being the ruling party, society would fail to function if it were not organised. Of course, the degree of satisfaction we have with either organisation entirely depends on where you sit.

If we examine the question from either the private or public perspective, it seems clear that if organisations did not exist, we would need to create them, because who/what else would address the following questions; what … ?

- Is the state of our economy?

- … and the world economies?

- Is the most important change taking place in our sector of the market?

- Are the demands of the environment?

- Is the impact on this business (or this government body)?

- Should we be planning for to ensure our long-term future?

- Products and services will be needed?

- Are our current capabilities?

- New technologies will help us?

- Are our strategic objectives?

- Specific actions must we take, and in what time-frame?

- Support will we need?

- Skills are present in our top management team and what others will we need?

- Kind of action plan can we agree on?

- Will be our communications strategy (internal and external)?

- Can we create as a roadmap or model, to provide a common picture of any change effort?

- Can we get each senior manager to define as criteria for success?

- Are the decisions to be made, or questions to be answered, at executive level?

- Specific sets of employees will be implementing change and, therefore, expected to understand the change?

- New skills will they need?

- Have we communicated to the executive and business levels about goals?

Why IT?

Why mention IT specifically? Largely because IT is now ubiquitous; it is almost inconceivable to imagine a business that is not dependent on IT in some form (even if it is simply an address on the Internet for a restaurant or public house perhaps, where potential customers can find information).

These days IT is not so much an enabler of change, but more of a catalyst. That does not mean IT is either ‘integrated’, or necessarily ‘aligned’ with the business of the business (in fact it is often perceived as being as remote, or insensitive, as it ever was). The issue is that some IT services/concepts have been taken on board by organisations in such a way that IT has become much more commoditised in some areas, and yet remains difficult to change at the fundamental level (by that we do not refer to the out-of-control, day-to-day change that is simply too easy to request and, indeed, out of control). The reference is to the change sometimes considered for fundamental services – which, in turn, comprise application building blocks and specific hardware – which is simply too expensive to contemplate unless major, material advantages will quickly accrue.

IT often does not know how to align to the business properly, and that leads to this misalignment; a statement which applies irrespective of the nature of the business – private sector, government or otherwise. This is not to say that people in IT do not try. It is quite common for IT to have senior staff members whose job it is to ‘represent’ different elements of the business. It is quite common to find, though, that these resources only have (at best) a tactical understanding of the business unit they represent. Most often they are recruited from within IT, and guess what? They have an IT view of the business.

They do not necessarily get involved with business strategy decisions or business planning sessions. Unfortunately, this lack of business understanding leads to a reactionary relation between IT and business. IT is instructed at the last minute that a new service or system must be built – or sometimes installed. Or worse, that the business has just purchased an expensive business software solution that IT must now support. In some cases, business buys a service and because of the nature of the Internet, is able to use the service – until something goes wrong, perhaps many months after purchase. At which time, IT is asked for support – often the first that anyone in IT even knew that a new IT system was in use!

IT needs to be involved with business planning and strategy sessions in order to truly align with the business. It is in this way that IT can be more useful. Some suggestions include:

- From the IT perspective; recommending solutions to automate business processes.

- And from the business side; providing IT management with early warnings about plans that will impact current skill sets, staffing or IT support/capacity needs.

For an organisation to exist without some strategic view of its second most expensive investment (people being the primary and most important spend) is tantamount to commercial suicide.

This is not to argue that IT changes or drives change to the organisation, it is a recognition that the business drive to reduce overheads through greater use of IT, will inevitably lead to organisational change. How to manage that change is not, however, necessarily in the gift of IT.

The business environment

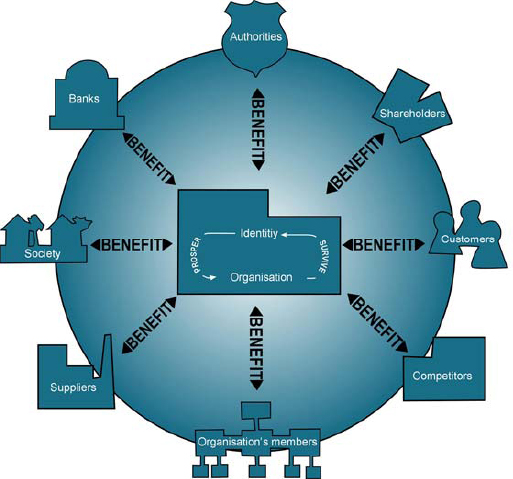

Figure 1: Business eco-systems

It is worthwhile spending some time considering the fundamental causes of change in business, and why some changes are easier to survive than others. Figure 1 illustrates some of the main business eco-systems. It illustrates what are institutionalised stakeholders; in each instance the organisation exists only to provide some form of benefit. Where the business is operating in a well-established sector, providing well-known products or services in a stable or niche market, it is likely that IT capabilities are well matched to business needs. Changes are unlikely to be dramatic and should be easy to manage and survive.

In such a situation, if the market begins to change, the synergy between the business and IT is probably reflected in the business and IS strategies for the future. In that case, IT will be an enabler of the changes and any business transformation. Although more risk is involved, survival is more a matter of good management and planning.

In situations where the business is operating in a stable market, and gaps are found between the business requirement for IT support, and the IT capabilities that are available to the business, fundamental change in IT is necessary. The ability to survive is, to an extent, dependent on the scale of the change and the speed with which it has to be undertaken, but once more the risks can be controlled.

If the capabilities of the IT organisation are not aligned with the business strategy, and the business capabilities of the business are not aligned with their market, then the business is presented with very significant challenges.

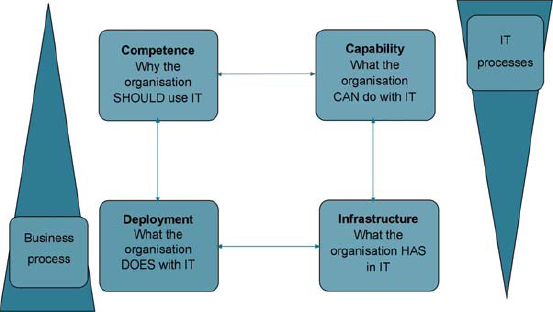

If IT is a significant stakeholder in change, should not then the business take a view on the capabilities in IT? Figure 2 provides a viewpoint for the business. Strictly speaking, the prevalent competence of your IT sets the stage for its deployment (what is possible); and the deployment is partially responsible for the business results.

Figure 2: How IT should be viewed by business

A required competence requires a set of IT capabilities, which, in turn, enable the organisation to use its IT effectively. The hardware and software used by IT is the infrastructure, and is (or should be) an invisible, but important, asset for the business, but one wholly managed by the trusted service provider. Changing the infrastructure of course means new capabilities, new competence requirements and, of course, should result in better deployment of IT.

The loop is one of continual feedback, with the elements necessarily influencing the other.

The deployment element, of course, creates demand upon the infrastructure and, in turn, the infrastructure is necessary to support deployment.

The business must be aware that change predicated on using IT will have implications across each element. This is further covered in Chapter 6. The key element of change then is its widespread effect.

For example:

- Decisions that you, and other managers, make in the business, are affected, e.g. where you would take one position on an investment in the past, you would now take a different position because of economic fluctuations.

- Usefulness of IT deployed in the business area in economic terms is enhanced (or reduced), since the methods to determine the degree of support, or perhaps the lack of it, have changed.

- The IT services used in the business area gradually change as the IT infrastructure changes (maybe because the business starts to procure IT services from outside, because it is seen to be more responsive than internal IT).

Organisations exist to provide benefit to a variety of putative stakeholders. Shareholders receive benefit from their investment in private sector companies, for example. Governments provide benefit to their citizens (though that might be a debatable point depending on where you live). Banks were initially created for purposes not entirely linked to getting rich at the expense of their customers, and many of the benefits are consequent on an eco-system of different organisations. All of these types of benefit are (or should be) the focus of the organisation created to provide them.

How the organisations are structured and managed is, however, unique, even in the same vertical sector. For example, government is government, but does anyone really believe that the French govern in the same way as the English? Or that politics in the US is not influenced by the media more than in any other country? Or that all countries have a free press?

The same is true of other organisations working in the same vertical, whether oil, pharmaceutical or IT; characteristics may be similar, but ways of working, management and pretty much everything else, may be labelled the same way, yet do not exist in the same way.

What is the function of the organisation?

As mentioned earlier, a cynical answer would be to ensure that it continues to exist, and sometimes cynicism is reality. If businesses are to flourish, an organisation and a hierarchy must exist. Even very small organisations exist primarily to serve themselves; a shopkeeper may have only one employee, but that employee exists to help maintain the business of that shop – the hierarchy is flat, but, nevertheless, it exists. And furthermore, the bullet list of questions that we began with at the beginning of the chapter, will be applicable, albeit at a level of effort commensurate with the scale of the business.

A new till may be a future purchase, for example, for a small corner shop business. Maybe the owner should buy a BlackBerry? Or in a large organisation, many BlackBerries, if the business wishes to improve communications. Or, maybe a shared workspace should be built/acquired to cut down on e-mailing … The point we are making is that boundaries often exist that are not bridged by one domain of expertise.

The crucial point is that all organisations are predicated on the Darwinian concept of ‘survival of the fittest’, even if they teach Creationism.

Corporate culture

So how do we get people to think across boundaries? Why is it important for organisations to work across boundaries? Is it speed and execution perhaps? We will elaborate on these issues throughout this book. We should also point out that elaboration is not the same as guidance. By and large, most organisations will face similar challenges, so we have created checklists that we believe all organisations will be able to use to orient their decision-making processes. But the question of guidance is another issue. Every organisation will have a different corporate culture and goals, and so it is impossible (and pretty stupid) to pretend that we – or come to that anyone else – has the single golden nugget that will change for the better everything that is, or should be, done. How you answer the questions in the context of your own organisation, is the most important factor; where possible, we provide some ideas and some examples that may assist, though, as we will often reiterate, there is no one, universal answer.

An example of perpetuating the organisation

Is there then one sure-fire way to help the organisation survive? Let’s take a look at a good example of how one organisation manages changes.

To facilitate change and improved business processes, the US Department of Defense provides official, documented guidance about authorised methods. One approach is corporate information management, which has a specific directive concerning change through automation. The directive suggests that you should think first about the best way to perform an important action, and then automate only the necessary information: avoid automating ineffective or unnecessary processes.

The US Department of Defense checklist for change includes:

- Adopt a business engineering approach to business management

- Focus on the mission of the business

- Identify the business activity to be evaluated

- Define the goals

- Create a strategy to achieve goals

- Identify options (through in-depth analysis of data requirements and business processes)

- Perform risk analysis

- Assess costs for the options

- Perform cost-benefit analysis to help decision making

- Create management teams for the programme of change

- Create plans for implementation

- Streamline, simplify, or consolidate added value activities

- Eliminate ineffective activities

- Improve business processes

- Take opportunities offered by IT to automate the improved processes

- Review progress regularly.

Fairly innocuous stuff really, and hard to argue with. One can see parallels with lots of published good practice. Unless your goals are not ‘Defense (spelled the American way) of the Nation … ’

A contrary view of this would be:

‘Nothing really changes does it? Those in power, stay in power. No vision, only procedures. Plenty of opportunity for red tape, scapegoating, etc. This stuff is more inclined to stifle change, rather than facilitate it. However, the list does illustrate “things that should be done”. But the most interesting thing is that even though the role and importance of the military might have changed since the fall of the Eastern bloc, it obviously has not changed their unduly rigorous views about handling change. No room for adaptation, no room for innovation. No room for anything except step-by-step precision.

Everyone is different and every change is different, so think about issues before you do anything. The Department of Defense goals of most likely, defending the nation*, do not bear any relation to goals of surviving transitions, prosperity, growth … Because their goals are based on their own, perceived, socio-economic importance – which has not changed even though the world has, and the world view of the socio-economic importance of the military is completely different.’

*Less contentious description of ‘Killing people more effectively’.

This book is not intended to provide specific answers to creation, or change to organisations, precisely because of the diversity of organisation types (and people running them), as this short example illustrates. It is, however, intended to discuss the issues facing all organisations, and to describe the methods that can be used to address some of those issues. The most important advice in here is that there is no silver bullet – no matter what someone tries to sell you.

In the next chapter, we will discuss some of the reasons why organisations change – some more frequently than others.