CHAPTER 3: CHANGE ISSUES

Introduction

The beginning of this chapter discusses conditions, goals and the environment. Later, we move onto describing solutions and approaches.

When changing the organisation, irrespective of the reasons for change, IT is unlikely to be the first aspect considered to be a problem; however, many issues will materially impact on the IT infrastructure and applications running on that infrastructure – together these are the services consumed by the business (and the customers of that business) to run its business(es).

Consider the following:

- The change driver – why are we changing the business and for whom? Business in this context could be a service to the public provided by government, or by the private sector; new or revised social security or taxation legislation, for example, or new banking services.

- The scope and nature of the change – which parts of the business are to change and how (and why … )?

- What new, or altered, business capabilities are required?

- What changes in IT deployment are required to support these?

- How acceptable are existing IT systems and capabilities?

- What are the compatibility requirements of the new or altered IT systems, and is there an opportunity for compromise, at least in the short term (in the instance of a merger or acquisition) (see also Appendix 1)? The last point is key – instead of a risky technical programme of change, can management (organisational) change be accommodated to allow parallel running?

- What architecture and design rules exist to govern the IT infrastructure post change, and what is the scope for transitional arrangements and compromises?

- What organisational and personnel issues affect the business, its use of IT, and its relationship with the IT providers?

- What is the current cost of IT and is it considered justifiable?

- What is the ability of the business and the IT provider (internal or external) to take the business and its IT from where they are now to where they need to be, in the required time-frame?

Other issues include competing for resources – generally resulting in projects competing for budget and increasing the time taken to get services to market (or the quality of services being delivered); varying degrees of maturity in terms of use of technology; trained personnel or processes being in place to facilitate both business and IT management – each of these points to an inefficient organisation. Often, the drive to reduce operational overheads, or to satisfy customers, leads to changes that were not properly planned or executed.

Six facets of the organisation

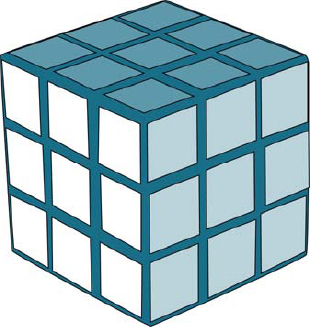

Consider Figure 5 for a moment and the allegory between changing the facets of a business and changing the alignment of the facets of a dice cube. Think of the cube as a well-known, trademarked puzzle!

Figure 5: The Perfect world

A business can be considered to have six major facets: strategy, process, organisation structure, technology, people and quality. Inevitably, someone or something, decides to change one of these facets because something – whatever ‘it’ is – is not working as it is perceived it should.

Maybe some nice, shiny new technology is needed by someone. And following changing out some old boring stuff for some new shiny stuff, things don’t work quite as expected. The next step is to change the organisation to make it work better. Or, maybe the strategy. Or, perhaps educate our people because, clearly, they are the cause of the problem. Perhaps the quality of the work needs to be improved, so we implement a programme to instantiate a quality approach.

Inevitably, in a dice/cubes analogy, the result will resemble a manipulated cube – and getting things back together in the same way, will be an impossible task. The changes must (from a business perspective) be managed holistically.

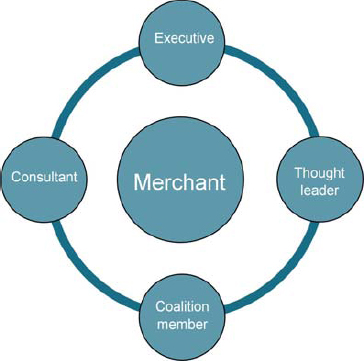

The politics of change

A major component of any change, and one that is very often ignored, is the political climate of the business. Culture is more often than not a phenomenon of the prevailing political climate – that is both small and large ‘P’. In Figure 6, if we consider that every business is a merchant of some flavour (even governments), then a number of major political elements can be recognised.

Figure 6: The political business

Any business created, and run, by its founder (usually then the CEO), will adopt the characteristics of the founder. Should the founder step aside, the way the business works will change, perhaps not immediately, but inevitably. Good examples include Apple and Microsoft. Where a founder takes all material decisions, it is very likely that an organisational structure will have been created to ensure that autocracy cannot be challenged. Many governments have been predicated on a system, such as this (and not all of them have fallen). Where these governments have fallen, the change (to democracy) creates its own challenges. Even a democracy is impacted by the nature of the governing body; not all democracies are the same and they reflect much of the nature of the leading political figure. The same is true of business change in such circumstances.

The way in which change is (or should be) managed is related strongly to the political ethos that prevails in the business.

For each quadrant of the diagram shown in Figure 6, the following dominant role models are described:

- The thought leader: these individuals seek an advisory role, with corresponding behaviour expected of people they work with (i.e. no ideas to be implemented ‘off the shelf’, adopt and seek to adapt ideas of others with more influence).

- The executive: this role is a decision maker, such individuals do not need to have ideas, it is expected that people will approach them with ideas and concepts.

- Coalition member: people with these characteristics lead through developing a common vision regarding change. They listen to, and incorporate ideas of, coalition members and the opposition (anyone who has ever worked in the Netherlands will recognise this type of conduct, sometimes the drive to get everyone to agree leads to stasis, since no one wants to move forward without agreement). Consensus leaders look out for, and partake in, the coalition corresponding most closely to their own ideas.

- The merchant: this position is determined by the ability to focus on sales. People, such as this are alert to trade-offs and are content with a suitable compromise – whatever it needs.

These roles are present in different degrees in all leaders; many organisations have one particular influence that is prevalent and change is managed according to that dominant trait (see comment about the Netherlands).

Political issues are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4 (see The political perspective revisited).

Catalysts for organisational change

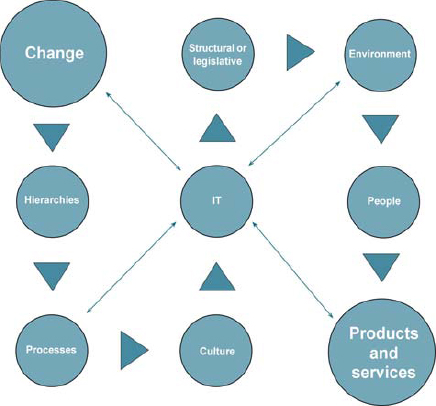

In the next sections, we will take a closer look at some IT catalysts for change. Why does change take place? Where does change originate?

Figure 7: Change can be driven from many domains

The short answer is ‘Anywhere’ (see Figure 7). As we have mentioned, a current (white) hot topic is Cloud Computing; a major technology driver that is predicated on cost (or rather, less cost), but few have addressed one major cost issue – the cost of changing legacy systems that were designed to run on a specific platform and that are likely to be huge COBOL systems.

At this point, someone somewhere will cite their favourite method as being suitable for driving the associated organisational changes that will be an inevitable consequence of the brave new Cloud-world. Unfortunately, those ‘someones’ tend to be IT people who consider (for example) the ITIL® as the ‘Bible’ on any subject and blithely recommend an ‘ITIL® compliant’ organisation as the solution. And, because everyone wants change to be easy, it is not uncommon for the IT or ITIL® ‘expert’ to be charged with changing the organisation.

The words ‘asinine’ and ‘risible’ spring to mind, but, being politically correct, let’s just say that it is somewhat misguided of IT ‘experts’ to expect to have IT leading the Board of Directors. This method of madness is also discussed later.

Legacy systems

Dealing with legacy applications is particularly pertinent to a period of organisational change, because the existing applications are what you start with. You would, no doubt, like to know how easily they can be changed and what they should be changed to. Various means can be used to assess how easy, or how difficult (and, therefore, expensive), it would be technically to change existing applications. You may also want to move your legacy systems to a new technical platform (think Cloud … ), in accordance with perhaps plans for a new ‘target’ information systems architecture. In fact, various options are available to you for dealing with your legacy applications:

- Refreshment – modification of an existing system in situ, to address specific requirements or limitations, and to extend the life of the system.

- Conversion – transfer of the application from one IT platform to another, as mentioned above (bear in mind that re-engineering of some description will be needed).

- Re-engineering – the identification and extraction of business functions by analysing existing systems, and the generation of a replacement system in any chosen technology (expensive, risky and time-consuming).

- Replacement – development of a new system to meet business requirements; the new system may replace some, or all, of the functions provided by the existing system.

- Replacement by the purchase of package software that has been built and proven by a third party; some element of bespoke development of software may also be needed to allow the package to meet your business needs.

The change issues are exacerbated by new technologies or the hype around new technologies. Cloud Computing, for example, is not really a new technology per se, unless it is a myth that business has been carried out over the Internet for the past 15 years. Cloud Computing is, however, a major driver for considering technology change to improve the ability of the business to control costs, and to innovate more rapidly.

It is also a cause of concern if all of the issues (for example the risks of changing platform, security issues, data ownership, cost of change, etc.) are not thoroughly addressed; the altered cube beckons.

Business goals

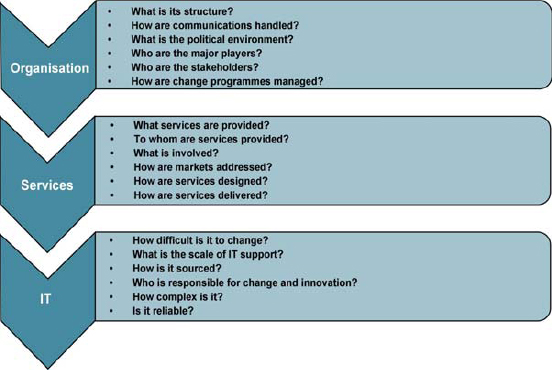

The ultimate IT goal is well-designed, architecture-conformant, integrated and flexible applications. From the business perspective, this is likely to be idealised as reliable, high-availability support from IT. The speed with which you move to this ideal will depend on the needs of your business. See Figure 8 for a list of the questions you may wish to ponder. If your priority is to have integrated and flexible systems, you will probably want to move faster than if your priority is to contain IT costs.

You will certainly want to make sure new applications are architecture-conformant, but you should decide what to do about existing applications on a case-by-case basis, depending on whether each application:

- Needs to be changed to meet business needs

- Is capable of being so changed

- Is worth changing to meet business needs and also, depending on whether, and how, each application can be accommodated on any new technical platform that is being introduced, to facilitate wider acceptance and increase use in the business.

Figure 8: Questions

Replacement options

Development

A new system development allows total flexibility in terms of technology and design. Definition, construction and verification of the system carries the normal risks associated with application software development, which includes creeping scope and subjective judgement of correct completion. The risks to a development project are also greatly increased if data processed by an existing legacy system needs to be carried across to the new system. The wider the disparity of functions between the legacy and the proposed replacement systems, the greater are the costs and the risks. Partial redevelopment is possible, for example, to replace obsolescent user interface software.

Package

The solution of buying packaged solutions should be cheaper than an in-house development, because the development costs are shared across all potential purchasers. The migration of legacy data into the package, and the addition of any functional areas not covered by the package, can, however, substantially increase costs.

Choice of technology can be limited by the range of hardware/software environments in which the package is implemented. To avoid problems, purchasers should always ensure that the package has been designed for the technology on which it is expected to run, and is not converted from a disparate, technical platform.

Success, or failure, in package selection, rests with the purchaser. An accurate specification of functionality and supporting data structures by the purchaser will facilitate selection of an appropriate solution. Early consideration of the issues associated with the migration of business data to fit the package will significantly contribute to the successful implementation of a package solution. It is important to recognise that the more specific the customisation of a package that is required by the business, the less satisfactory this option will be and, in particular, the greater will be the costs and risks.

Approach to legacy software issues

Understand the asset

A comprehensive analysis of the existing IT application portfolio will result in an objective assessment of its strengths and deficiencies. It will also provide a template for assessing its appropriateness for the future.

Define business requirements

Prioritise the requirements for future changes and establish the timescales in which they must be achieved. Although requirements will inevitably change with circumstances, the degree of change in requirements should be kept to a minimum, because a moving target can frustrate the ambition of change.

Compare options for change

Examine the options for change to see which best satisfies the business requirements. A combination of options may be appropriate where different parts of your systems have different characteristics.

Perform a cost-benefit analysis

Having identified viable options, for each of these (including the ‘do nothing’ option), establish the costs and risks, and compare them against the benefits which will accrue to the business. The assessment should take account of the risks resulting from introducing new technology, extending functionality, or imposing restrictive timescales.

The cost-benefit analysis may suggest a different option for change than that initially considered to be the most likely. A change, of course, at this stage may save later embarrassment and expense, but is only possible with a comprehensive understanding of the legacy asset and environment, and an awareness of the range of options for change.

Changing the IT infrastructure platform

It isn’t just the IT applications that you have to look at, the underlying IT platform infrastructure, comprising hardware, telecommunications facilities and supporting general purpose software, such as operating systems, may also need to be changed. Here are some of the questions to ask about the underlying IT infrastructure:

- Does it conform to a well-defined, up-to-date architecture?

- Is it capable of enhancement, to provide more capacity and to accommodate new applications?

- Does it support the levels of integration that will be required?

- Can it be regarded as mainstream, or is it obsolescent, or in a cul-de-sac?

- Does it, or can it, support technological innovation?

- Does it support current and foreseen needs for IT applications?

- Is it aligned with our longer-term thinking?

The ultimate goal can be further elaborated as a flexible, well-designed infrastructure that supports the integration of data and of applications, and that is based on a judicious mix of desktop, departmental, central and Cloud-based IT facilities, each of which adheres as far as possible to de jure, or de facto standards, or to available public specifications.

Wherever possible, new IT infrastructures should conform to the business architectural standards, but these must be flexible enough not to stifle technological innovations. Such new infrastructures need not be installed in a ‘big bang’, but gradually, over a period determined by the immediate and long-term needs of the business for IT support. It may be possible to build on the existing IT infrastructure in order to cope with the change.

Service delivery improvements

A major public service employer was examining approaches that would enable them to provide better services to the public. The major obstacle was considered to be the culture of the business, which was steeped in tradition and hierarchical structures. The following is a list of the elements that had to change in order to improve the service delivery processes. They decided to:

- Evolve a more outward looking culture

- Eradicate bureaucracy and tradition

- Use HR to reinforce required behaviours

- Improve internal communications

- Amplify the need for roles, rather than specific grades, within hierarchies

- Improve staff morale

- Examine how services were offered and described

- Improve the supporting processes (e.g. managing incidents and problems more effectively)

- Base organisational structures around the management of business processes

- Use IT to automate labour-intensive processes

- Deploy IT in a more strategic role, based on a new applications architecture

- Ensure that business goals were reflected in the new organisation

- Identify and quantify service demands

- Gear change proposals to meeting standards of service and negotiated expectations of customer’s requirements

- Take into account, but not be constrained by, previous investments

- Require absolute, demonstrable commitment from the top.

A major change issue: Outsourcing

Outsourcing is a major change issue, with repercussions across all six elements of our organisational cube. Outsourcing is most often discussed in the context of IT, though it is no less often used for cleaning, HR, finance, logistics, security and many other services.

Outsourcing can be both an inhibitor of change and an enabler (depending upon perspective – and how well the contract was negotiated!).

Outsourcing – inhibitor of change

Over the years, it has been possible to collate a range of opinions about the possible benefits and risks of outsourcing.

Issues discussed included:

- Loss of professional IS/IT competence in the company

- Difficult to revert to in-house provision

- Ill-defined and ambiguous contracts, leading to disputes

- Little or no integration with corporate business

- Wasted time spent on disputes about costs, scope of contract, estimates, service quality, etc.

- Increased (even misplaced) dependence on the supplier

- Costs greater than anticipated

- Personnel unsettled

- Loss of flexibility, through being locked-in to the supplier’s proprietary methods and tools

- Poor quality of software development; assistance required from within the company that was not anticipated

- Putative cost reductions in technology not achieved in reality because of long-term contracts

- Failure to recognise the need for specialist skills in contract management, contract negotiation and supplier management

- Managing contracts costs money and time, much more than originally believed

- Slow response to change

- Service levels

- Poor programme/project management, leading to delays and increased costs

- Profit takes precedence over business

- Complexity in managing both the outsourcing supplier and other third-party suppliers

- Long lead times before service quality is adequate

- Poor control of the contract exercised by both customer and supplier

- Unrealistic notions of the service levels negotiated with the supplier by the business and its end users

- Strangely, the business and its users dislike having to pay money for IT, especially to an external supplier – which leads to the question: why did they take that direction?

Outsourcing – facilitator of change

On the other hand, some customers of outsourcing suppliers of services cited a number of benefits that they believed were attributable directly to outsourcing:

- Immediate, effective application of professional standards

- Fewer people needed, fewer in-house specialists

- More cost-effective (and efficient) PC maintenance

- Problems often anticipated, leading to a reduction in major problems

- Smaller range of IT services requiring direct management

- Reduced bureaucracy

- Improved budgetary control

- A more customer-oriented IT service approach is often developed

- Business managers are free to focus on strategic issues, ensuring that they can focus on the needs of the business and less on the needs of users receiving a reliable level of service

- Business managers understand, and often value more fully, the contribution of IT

- Reduced total IT costs

- Predictable costs

- Faster services or systems development

- Developments delivered on time and to budget

- Third parties (e.g. network suppliers) find it easier to deal with changes through the outsourced IT supplier, reducing incidents, problems, delays and costs

- Users prefer to pay an external supplier rather than internal providers, because internal equates to free!

Some of the items appear in both of the lists; not surprising since outsourcing is an emotive issue and what one person considers a positive, another might consider a negative. The range of opinion will also be affected by where the individual sits (in or out of the organisation – maybe in or out because of the outsourcing).

It may appear to be anomalous, but it may also reflect the fact that a business spending more time on contract negotiations and using specialist advisers, obtains better results from outsourcing. Of course, even then the interviewees are blinded by their own preconceptions, good or bad. The reality, however, is that outsourcing is more successful if it is carefully planned and auctioned. In terms of IT, that is a lesson for those considering a move to Cloud services.

Consider again the cube analogy: small changes to one component find a way to becoming changes that cannot be foreseen. And, unlike the cube, you cannot find a key to put things back together.

Internal communications

Internal communication in times of change cannot be underestimated in terms of its importance. You need to have confidence that your personnel and contractors will understand why the change is being made, what is intended, and how they can help to bring it about. If you fail to communicate effectively, there is a major risk that people will thwart the change, rather than help to achieve it.

Branding a change programme to help with communications and to get people ‘on board’, is often a good idea. However, assuming that branding will solve all motivation issues, is not. By that, we mean that communications problems, once identified, are presumed to be easy to solve. Often change is managed at multiple levels, inadvertently creating tensions, false or unrealistic expectations, and the opportunity for disaster in terms of delivery. A good example is where organisations create executive sponsorship of projects (internal or external), delegating programme and project management appropriately, and then filling in resources at the coalface to do the necessary work.

At executive level, there is the desire to maintain a positive approach, to present the best possible picture of success. At the management level, this is met by selective presentation of information, not out of malice or even cowardice, but simply to maintain support. Often, issues or problems are discussed, but not sufficiently robustly, until the issue or problem has become a crisis.

Meanwhile, at the working level, there is increasing frustration that the management and executive level are failing to act on information that requires detailed attention, and action, in order to succeed. At this level, people become afraid of being scapegoated.

A project brand does nothing more than enable people to acknowledge a sense of ownership; it does not increase motivation, or change the way messages are passed through management layers. Of course, when things do go wrong, and executive management is forced to intervene, then often you will find that they look at how the project has been managed and then insert ‘missing’ good practices – obvious candidates being a communications plan where one did not exist, or a brand for the programme. Another regular intervention is the motivational speech featuring executives focusing on the wonderful opportunities, the valuable team members and how regular feedback sessions, led from the top, will get the programme back on track. Unfortunately, this does not solve the problem of no one wishing to be the bearer of bad news, until it is too late to act.

The tendency to optimism is a human characteristic that sadly leads to more inquests about ‘what went wrong’, then basic ineptitude. Further, the tendency at this point is to go into a full post mortem, project evaluation review, post implementation review – select your most used term – and the fickle finger of blame is pointed.

And then the workforce is vindicated in their fear of scapegoating.

None of the above is to suggest that executives, managers or workers lie, connive or deliberately conceal. It is simply a matter of fact that most change programmes that fail, do so because bad news is communicated either badly, or too late, or glossed over in the belief that hard work will make it go away.

We cannot solve this, but below you will see some of the questions to which you will need answers:

- What information (programme, project, goals, critical success factors (CSF), risks) do you need to communicate?

- How do we ensure that from the start, all possible problems and risks are documented, shared at all levels and a response recorded (see The Agenda in Chapter 4)?

- How will this document be tracked to ensure that issues are regularly reviewed, and that people are held accountable for decisions made about risks and problems?

- How can we ensure that information is focused, approved and endorsed business wide?

- Who are the decision makers?

- What are the target audiences?

- What do we want to achieve from this communication?

- When do people need the information?

- How can we provide the right information, at the right time to the right people?

- What is the most effective method of delivering the information?

- How will the results be measured?

- How will we know that the information has been understood?

- How can we ensure communications work two ways, giving and feeding back?

- Would discussion groups be effective?

- Can we use senior managers to illustrate commitment to change?

- Can they be held accountable for addressing risks and problems at an early stage?

- How much will it cost to communicate properly?

- How much will it cost if we fail to communicate properly?

- How many channels for communication exist in the business and is their use effective (in other words, is one forum for discussion better than a multi-tiered approach, and if not, how do we ensure that each tier addresses the same issues)?

- How do we continue the good practices post-change?

- What lessons have we learned that we will put into practice for the next change programme?

IT capability

If you are concerned about the capabilities of IT to deliver effective programmes of change, then that concern is probably wise. Ineffective IT is a ubiquitous problem and the statistics on successful IT projects are far from encouraging – but you can minimise the risks. If you have time, you may be able to do something with your existing IT in advance, to prepare it for the change. More likely you will have to prepare your IT during the change for the new business operations. In other words, your existing IT may not be a good starting point, but you will probably have to put up with that.

The quality of IT service provision can impact, positively and/or negatively, on:

- The smooth running of the ‘old’ business during the change

- The smooth introduction of the ‘new’ business during, and after, the change.

Business change will be successful only if the old and new businesses run smoothly, in accordance with the programme plan for the change. As far as possible, your IT should help you to achieve these objectives. You should certainly take steps to make sure your IT does not prevent you from achieving them.

To help you to understand the impact of IT on the business change, you will need answers to at least the following questions:

- Do we understand the strengths and weaknesses of our existing IT?

- In particular, what are our existing IT’s change capabilities?

- What time do we have to get our IT ready to cope with the business change?

- Is there an IT architecture, or strategy, or blueprint which sets the direction for IT change in the business? Do we understand the IT changes that will be needed alongside the business change? What new capabilities are needed? What new systems? What changes to underlying IT infrastructures?

- Do we have a programme plan which sets out the milestones for IT change during the business change?

- Does the programme plan include provision for the smooth running of the old IT, as the new IT is phased in?

- Does the programme plan allow for risks to the programme? In particular, what contingency is there to allow for slippage in the timescales for IT change, or for IT projects that fail to meet expectations?

- Is the degree of IT resourcing realistic and achievable? Does the business’s IT provider have enough of the right skills available?

- Are there enough funds for IT?

- Is there a fall-back position for each IT change? What can be salvaged if any such change should fail? Can we say which requirements can be deferred, or dropped, and which are essential if the IT projects get into trouble?

- What are the arrangements to make sure the business can assimilate the various IT changes? Who is responsible for making sure the proposed changes are acceptable to the business; for defining the new way of working; for testing the changes on behalf of the business; for training the business users; for accepting the IT changes on behalf of the business?

- What arrangements are there for phasing out the use of the old IT by the business?

Dependencies

Where there are interdependencies between projects, or there is a likelihood of knock-on effects from one project to another, these should be clear in your programme plans. It is a responsibility of the programme manager to make sure these interdependencies and knock-on effects are properly managed.

The business environment may well change rapidly, perhaps in unpredictable ways during the change, or the objectives of the programme may change. Again, it is a responsibility of the programme manager to make sure changes to the programme are translated into changes to IT-related projects within the programme.

Preparing for the impact of change on both business and IT is concluded only after you have considered all of these issues. Only then will the ‘new’ IT be fully alerted to support the new business operations, or, at least, as close to being able to identify its definitive form as your planning deems appropriate.