11. Pimp My Ride

ISO 50 • 3.2 sec. • f/20 • 24mm lens

Upgrades and Accessories to Expand Your Camera’s Creative Potential

If you bought your camera with a lens, then you basically have everything you need to begin shooting. I took great care to ensure that almost all of the techniques covered in the book are not beyond your basic camera setup. That being said, there are some accessories that are essential for certain types of photography. Other accessories aren’t necessarily essential, but they will improve the look of your images. Then there are the gizmos and gadgets that won’t make your images look any better but they will make your shooting experience more enjoyable.

Just one word of caution when it comes to photography accessories: Don’t let yourself get in the mindset that the gear is more important than the technique. Buying photo accessories can become habit forming. It’s easy to think that the next big filter or flash modifier is going to put your photos over the top, but there is no substitute for good old-fashioned practice and skill. Buying gear can be fun but it shouldn’t overshadow the importance of a good basic skill set. Now let’s take a look at some items that I believe are must-have accessories for your photography.

Filters

You should have several filters in your camera bag. Each one serves a unique purpose. Some say that digital imaging programs such as Adobe Photoshop can duplicate the effects that the filters offer. This may be true, but I would rather screw on a filter than spend countless hours trying to replicate an effect on my computer. Here’s another benefit to using a filter: lens protection.

Skylight

Probably the cheapest—yet one of the best—investments you can make for your camera is a skylight filter. This filter is used more for its protective effects than for any visual boost. At one point in time, the skylight, UV, and haze filters were used to filter out UV light in order to add sharpness to distant subjects, correct a minute bluish color cast, and reduce the effects of haze in a film image. A digital camera offers the benefit of having filters that are built into the camera in front of the image sensor to eliminate the effects of UV and infrared light. Therefore, most of the visual benefits of using a skylight filter are not evident. So why, if there is no real visual difference, should you use a skylight filter? Because what they do offer is protection for your valuable lens for a relatively low price.

For example, a Canon EF-S 18–200mm IS lens will cost you about $600. A 72mm HOYA Skylight 1B filter costs around $40. As someone who often either forgets or loses lens caps, it’s reassuring to me that a $40 filter protects the precious glass on the front of my lens without degrading the quality of my image. If it does get scratched, I just unscrew it and buy another. That beats the heck out of $600 or thereabouts to replace or repair a scratched front lens element.

Polarizing

This one ranks right up there at the top of the list of must-own photography accessories. You won’t find a self-respecting landscape photographer who doesn’t have at least one polarizer in his camera bag (Figure 11.1).

Light travels in straight lines, but the problem is that all those lines are moving in different directions. When they enter the camera lens, they are scattering about, creating color casts and other effects. The polarizer controls how light waves are allowed to enter the camera, only letting certain ones pass through. So what does that mean for you? Polarizing filters will make blue skies appear darker, vegetation color will be more accurate, colors will look more saturated, haze will be reduced, and images can look sharper (Figures 11.2 and 11.3). Not bad for a little piece of glass.

ISO 800 • 1/125 sec. • f/11 • 120mm lens

Figure 11.2 Without using the polarizing filter, the scene looks a little low on contrast and has a blue color cast from the sky.

ISO 800 • 1/60 sec. • f/8 • 120mm lens

Figure 11.3 After adding a polarizer, the colors are much more accurate and the color cast is now gone.

Most polarizers are circular and allow you to rotate the polarizing element to control the amount of polarization that you need. As the filter is rotated, different light waves will be allowed to pass through, such as a reflection on a lake. Turn the filter a little and the light waves from the reflection are blocked, making the reflection disappear. Another benefit of the filter is that it is fairly dark, so when used in bright lighting conditions, it can act as a neutral density filter (you’ll learn more in the next section), allowing you to use larger apertures or slower shutter speeds. The average polarizing filter requires an increase in exposure of about one and a half stops. This won’t be an issue for you since you will be using the camera meter, which is already looking through the filter to calculate exposure settings. You should consider it, though, if your intention is to shoot with a fast shutter speed or use a small aperture for increased depth of field.

Neutral Density (ND)

Sometimes there is just too much light falling on your scene to use the camera settings that you want. Most often this is the case when you want to use a slow shutter speed, but your lens is already stopped down to its smallest aperture, leaving you with a shutter speed that’s faster than you want.

A classic example of this is shooting a waterfall in bright sunlight. To get the silky look to the water, the shutter speed needs to be about 1/15 of a second or slower. The problem is that a proper exposure for bright sunlight is f/16 at 1/100 of a second with the camera set to ISO 100 (this comes from the Sunny 16 rule). If your lens has a minimum aperture of f/22, the slowest shutter speed you would be able to use is 1/50.

The way around this problem is to use a neutral density (ND) filter to make the outside world appear to be a little darker. Think of it as sunglasses for your camera. ND filters come in different strengths, which are labeled as .3, .6, and .9. They represent a one-stop difference in exposure per each .3 increment. If you need to turn daylight into dark, a .9 ND filter will give you an extra three stops of exposure. You can also get yourself a variable ND filter (Figure 11.4) that allows you to dial in just the amount of neutral density that you need. In my earlier example, you could get an exposure of f/16 at about 1/10 of a second if you dialed in three stops or used a .9 ND filter. This would be a good starting exposure for getting silky smooth waterfalls (Figure 11.5).

ISO 50 • 5 sec. • f/7.1 • 45mm lens

Figure 11.5 Using a five-stop ND filter allowed me to use a long shutter speed in broad daylight to capture this silky smooth waterfall image.

To see more Singh-Ray filters, check out singh-ray.com.

Graduated ND

Another favorite of the landscape photographer, the graduated ND has the benefit of the standard ND filter but graduates to a clear portion. This allows you to darken just the upper or lower portion of your scene while leaving the other part unaffected (Figures 11.6 and 11.7 on the following page). This filter is most commonly used to darken skies that are too bright without affecting the foreground area. If a regular ND is used, the entire area will get darker, so there is no visual change in the image as far as the brightness ratio between the sky and the ground is concerned.

You can purchase the graduated ND as a screw-on filter, but most photographers prefer to use the larger 4×6” version, which allows them to control exactly where the filter transitions from dark to transparent. There are many different options when looking for graduated ND filters, such as the density factor (number of stops), as well as how gradual the transition is from dark to clear.

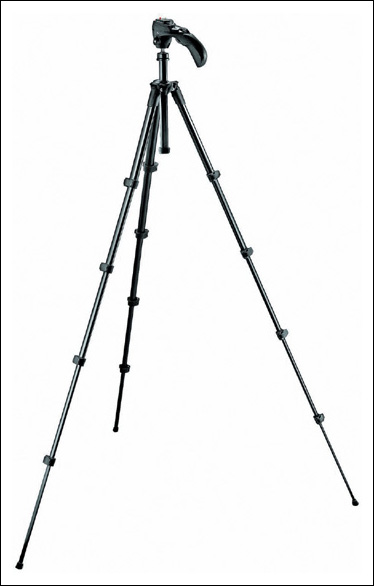

Tripods

If you only buy one accessory for your photography, do yourself a favor and make it a tripod (Figures 11.8 and 11.9). In general, any tripod is going to be better than no tripod at all. A tripod makes your photos sharper and lets you shoot in any lighting condition. There are more choices in tripods than there are in DSLRs. So how do you go about choosing the right one for you? The main considerations are weight, height, and head.

The weight of your tripod will probably determine whether or not you will actually carry it along with you farther than the parking lot. Many different types of materials are used in tripods today. The lightest is carbon fiber, which is probably the most expensive as well. More than likely, you should consider an aluminum tripod that is sturdy and has a weight rating that is suitable for your camera as well as your lenses.

Make sure that the tripod extends to a height that is tall enough to allow you to shoot from a comfortable standing position. Nothing ruins a good shoot like a sore back. Taller tripods need to be sturdier to maintain a rigid base for your camera. You will also want to consider how low the tripod can go. If you want to do macro work of low-level subjects such as flowers, you will need to lower the tripod fairly close to the ground. Many new tripods have leg supports that allow you to spread the legs very wide and get the camera low to the ground.

The other determining factor when purchasing a tripod will be the type of head that it employs to secure the camera to the legs. There are two basic types of tripod heads: ball and pan. Ball heads use a simple ball joint that allows you to freely position the camera in any upright position and then clamp it down securely (Figure 11.10). This type of head is flexible and quick to use, but it can sometimes be difficult to switch between portrait and landscape orientations. They also tend to be slightly more expensive as well.

Pan heads employ a swivel and usually two hinged joints that allow the camera to pan left and right, move up and down, and adjust the position along the horizontal axis (Figure 11.11). Handles are typically employed to allow movement of the camera and lock down the position. The pan head is by and large the most popular tripod head style on the market. If you have a DSLR that also shoots video, you might want to consider the pan head style since it will deliver more functionality for your videography, specifically panning from side to side.

If you really want to make your tripod shooting move faster, consider buying a tripod that utilizes a quick-release head (Figure 11.12). There are many styles of quick-release brackets; most use a small plate that screws into the bottom of the camera and then quickly locks into and releases from the tripod head. This locking plate function will let you move quickly from a hand-holding situation to a tripod with minimal effort.

The other thing to consider when purchasing a tripod is the leg locking system. Whether it is a lever-lock, locking rings, or some other system, make sure that you test it thoroughly to see how easy it is to lock and unlock the leg positions. Also check to see how smoothly the legs retract and extend. Avoid legs that stick because they will probably only get stickier over time.

You can find more information on Giottos tripods and accessories at www.giottos.com. Manfrotto tripod products can be found at www.manfrotto.com. For more info on the Benro tripod visit www.benro.com.

Cable Release

When shooting long exposures, you can use the self-timer to activate the camera or you can get yourself a cable release (Figure 11.13). The cable release, which is an electronic release, attaches to the camera via a remote port and lets you trip the shutter. It is also the preferred tool of choice when shooting with the camera set to Bulb (see Chapter 10). The idea of the release is that it allows shutter activation without having to place your hands on the camera. This is the best way to ensure that your images will not be influenced by self-induced camera shake. If you want to purchase a wireless remote, make sure that it will work from behind the camera as well as in front. Most wireless remotes use an infrared system and need to “see” the sensor on the front of the camera to work. This is great for taking self-portraits but not so good when you want to work from behind the camera.

Figure 11.13 A remote cord like this Canon 60E3 lets you activate the shutter without touching the camera.

Macro Photography Accessories

Extension tubes

Extension tubes are like spacers between your lens and your camera. The tubes are typically hollow, and their sole purpose is to move the rear of the lens farther away from the camera body (Figure 11.14).

Figure 11.14 Extension tubes like these from Kenko allow you to get macro shots from a variety of lenses.

A lens can only get so close to a subject and still be able to achieve a sharp focus. This is because as the subject gets closer, the focal point for the lens moves back to a point where it is behind the image sensor. Using an extension tube lets you move that focal point forward by placing the rear of the lens a little farther away from the camera sensor, thus letting you get the lens closer to the subject and enlarging it in your picture.

The tubes come in varying sizes, which are typically measured in millimeters. The more common sizes are 12mm, 20mm, and 36mm. The longer the tube, the greater the magnification factor (up to 1:1). The tubes are best used with lenses that are 35mm in focal length and longer. A wide-angle lens will have such a short focusing distance that you will be right on top of your subject. Many camera manufacturers, like Canon and Nikon, make extension tubes, or you can buy them from third-party manufacturers. Prices vary, but you will pay more for tubes that utilize optics in their design. You can also purchase sets of tubes with varying lengths that can be used individually or stacked together for greater magnification.

Close-up filters

Another great way to jump into macro work is by purchasing a close-up filter (Figures 11.15 and 11.16). Close-up filters also come in varying magnifications but tend to be a little more expensive than extension tubes. This is because they are usually made of high-quality glass that works in concert with the lens. The filters and lenses can have some advantages over tubes, too. Because they screw onto the front of your lens, they don’t interfere with any of the communication functions between the lens and camera body. They also result in less loss of light, so exposures can be slightly shorter than when you’re using extension tubes. They do, however, work similarly to tubes in that they allow you to shorten the minimum focus distance of your lens so that you can move closer to your subject, thereby increasing the size of the subject on your sensor. Close-up lenses usually come in magnification factors like +1, +2, +3, +4, and +5. They can also be stacked, strongest to weakest, to increase the magnification factor.

Figure 11.15 The Canon 500D close-up filter can be used on any make or model of lens but must be purchased by lens filter diameter.

ISO 400 • 1/30 sec. • f/5.6 • 70mm lens

Figure 11.16 A close-up filter was used to help capture this flower image.

The other difference is that they are usually screw-threaded onto your lens, which means that you have to purchase a specific thread diameter. So if your favorite lens has a 68mm filter thread, this is the size you would use for the close-up filter. The big downside is that if you want to use different lenses that have different thread sizes, you will have to buy multiple filters. This is why I prefer to work with a zoom lens so that I can have a range of focal lengths to use with just one filter. Also, just as with most glass filters, the larger the diameter, the higher the price.

Hot-Shoe Flashes

Earlier in the book I covered the built-in flash and what you can accomplish with it. Now that we have covered that, let me say that you really, really need to get yourself a hot-shoe mounted flash if you want to take better flash images (Figure 11.17). For one thing, the external flash is going to be much more powerful than the pop-up version. Also, there is much more flexibility built into the external flashes than you could ever hope to get from the built-in version.

Figure 11.17 A Nikon SB-700 (left) or a Canon 430EX II (right) flash unit will add power and flexibility to your flash photography.

Most manufacturers make at least one—if not two or three—different hot-shoe flashes for their cameras. They can be a little pricey, but the flexibility of being able to move the flash head and redirect the light is well worth the price. Another benefit to this style of flash is the added power. Most hot-shoe flashes have at least twice the power of a built-in flash, and they also throw a wider swath of light, meaning you can illuminate a larger area.

The third benefit is their mobility. You can add a remote flash cord and move your flash completely away from the top of the camera while maintaining all the functionality. This will let you expand your lighting possibilities to areas that a pop-up flash could never hope to achieve.

Diffusers

While I am covering flashes, let’s discuss a tool that lets you improve the light you are using in your portrait photography. A diffusion panel is a piece of semitransparent material, usually white, that you place between your light source and your subject (Figure 11.18). The fabric does as the name implies: it diffuses the light, spreading it out into a soft, low-contrast light source that makes any subject look better. You could make your own or buy one of the many commercially available versions. I prefer the 5-in-1 Reflector Kit made by Westcott. It not only has a very nice diffusion panel, but it also has reflective covers that slip over the diffusion panel so that you can bounce some fill light into your scene. Best of all, the entire system is collapsible, so it fits into a pretty small package for traveling.

You’ll find more information on Westcott diffusion panels at www.fjwestcott.com.

Camera Bags

This topic is tricky because I have yet to find the perfect bag for my own gear. All I can do here is tell you what I like to use and let you base your opinions on that.

First of all, I like to travel with my photo gear. Typically, my travel involves flying. This means that all of my camera equipment will be traveling in the cabin with me, not in the luggage compartment. I can’t emphasize this enough: Do not pack your camera in your checked luggage! Thousands of cameras, lenses, and accessories are lost and or stolen from checked luggage each year. The best way to ensure this doesn’t happen to you is to bring it on board and place it in the overhead storage. I like to travel with my laptop as well, so I have found a couple of backpack camera storage systems that allow me to fit a camera body, several lenses, some accessories, my laptop, and even some snacks into one backpack-style bag that still fits under the seat in front of me. I also prefer a backpack because I like the freedom of slinging the bag over my shoulder, leaving my hands free for other luggage. I am currently using a Kata MiniBee-120 for most of my travel needs (Figure 11.19). The thing that I really like about this bag is that it is extremely configurable and the yellow interior makes it really easy to find everything inside.

The other bag that you should look into is a more traditional, shoulder-style bag. These bags are made to handle all sorts of camera bodies, lenses, and accessories, and they’re usually completely configurable with moveable padded partitions so that you can completely customize the bag for your own needs. My current bag of choice is the Lowepro Pro Mag 2 AW (Figure 11.20). This small-looking bag just swallows up my gear and never quite seems full.

These two bags are the ones that I am using currently, but finding the perfect camera bag is truly the Holy Grail for photographers. The fact is that you can go through a lot of them searching for one that perfectly fits your every need and never find it. I know; I have about six bags presently taking up residence in my closet.

You can check out the full line of Kata bags at www.kata-bags.us and look for more info on Lowepro camera gear at www.lowepro.com.

Bits and Pieces

Since I just covered camera bags, let me share with you a couple of items that always travel in my bag.

The battle against dust is always a losing one, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t have your small victories. To help in the war against the dust speck, I carry three weapons of cleanliness.

The lens cloth

A good microfiber lens cleaning cloth always comes in handy for getting rid of those little smudges and dust bunnies that seem to gravitate toward the front of my lens. I use one called a Spudz, which folds into its own pouch and has the added benefit of being gray (Figure 11.21). This means that I can use it as a gray card to get meter readings in Spot metering mode, or as a way to correct the white balance in my images down the road when I bring them into my imaging software.

More information on Spudz cleaning cloths can be found at www.bhphotovideo.com.

The LensPen

For really stubborn smudges on my lens, I pull out my trusty LensPen (Figure 11.22). This nifty little device has a soft, retractable dust removal brush on one end and an amazing cleaning element on the other that uses carbon to clean and polish the lens. It comes in a variety of sizes that will take care of everything from your lens to the viewfinder to the rear LCD screen.

More information on LensPen products can be found at www.lenspen.com.

Air blowers

Some folks prefer to use canned, compressed air to blow away dust but they can sometimes release fluid when the can is tilted. For this reason, I always use my Rocket-Air Blower from Giottos (Figure 11.23). This funny-looking device is great for getting rid of tough dust, and it uses a clean air path so that the dust that you are blowing away doesn’t get sucked into the ball and re-deposited back on your equipment the next time you use it. At less than $10, it is something that everyone should have in their camera bag.

Better LCD vision

Having a large LCD screen is an amazing thing. The only problem is that it can be very hard to see in bright daylight conditions. The way I overcome this is by using a Hoodman HoodLoupe (Figure 11.24). The loupe doesn’t magnify your screen; it just provides a light-tight little tent for you to get a better look at your rear LCD. It has a handy little lanyard so you can just let it hang around your neck and keep it within easy reach for checking out those great shots you just took. If you are going to work out in the bright sun, you will definitely want to get yourself one of these for your camera bag.

To check out all of the Hoodman accessories, head to www.hoodmanusa.com.

Conclusion

You can spend a lot of time worrying about having the right gadget, filter, or accessory to make your photography better. It can become an obsession to always have the latest thing out there. But here’s the deal. You already have almost everything you need to take great pictures: a good camera and the knowledge necessary to use it. Everything else is just icing on the cake. So, while I have introduced a few items in this chapter that I do think will make your photographic life easier and even improve your images, don’t get caught up in the technology and gadgetry.

Use your knowledge of basic photography to explore everything your camera has to offer. Explore the limits of your camera. Don’t be afraid to take bad pictures. Don’t be too quick to delete them off your memory card, either. Take some time to really look at them and see where things went wrong. Look at your camera settings and see if perhaps there was a change you could have made to make things better. Be your toughest critic and learn from your mistakes. With practice and reflection, you will soon find your photography getting better and better. Not only that, but your instincts will improve to the point that you will come upon a scene and know exactly how you want to shoot it before your camera even comes out of the bag.