For experienced presenters

In this chapter

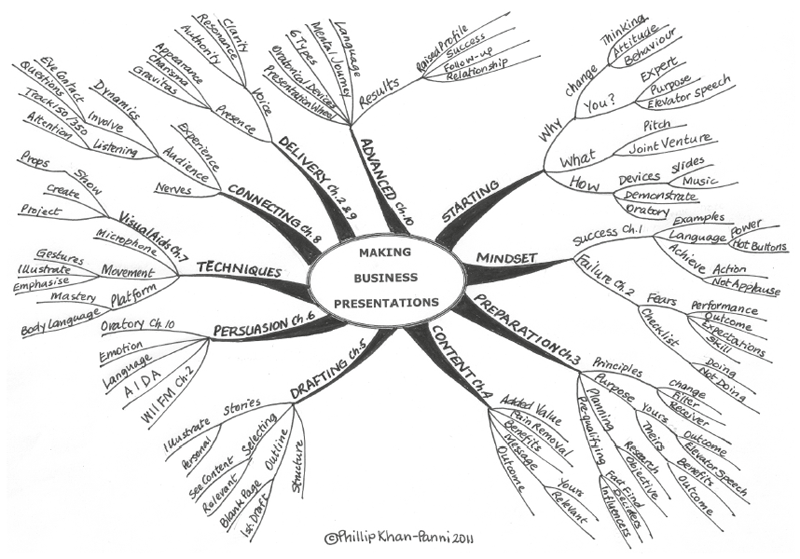

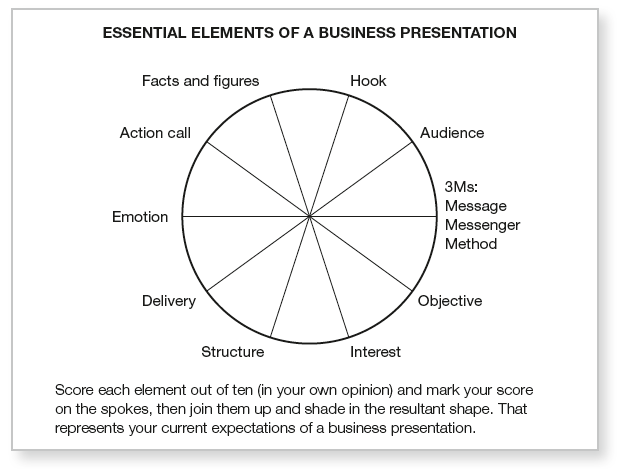

- The presentation wheel

- Six different kinds of presentation

- The right language

- Oratorical devices

- The emotional journey

This book is about persuasive business presentations. It is about the process of changing the way others may think about the issues you want to discuss, so that they are prepared to take the action you propose. It involves providing evidence and a well-structured case that builds on what the audience already knows and takes it on a notch, because change is not easily accomplished in giant strides. Part of the process is meeting the expectations of your listeners.

This chapter is about a level of understanding that goes beyond the mechanics of putting together a presentation and delivering it competently. It is about managing the emotional journey created by your presentation, and about the language and techniques that skilled orators use to reach the hearts of their hearers.

What follows is a wheel diagram with ten spokes. They represent the ten most important elements of a business presentation. The diagram provides you with a means of measuring how closely your own expectations might match those you might be addressing.

Make a photocopy of the diagram and mark each element out of ten for importance, in your own opinion, by marking a dash on the spoke. Zero is at the centre of the circle, and ten is on the rim. When you have marked your ten scores, join up the dashes, and you will see a shape that represents your preferences.

Next, make another copy and give it to someone who is similar to the kind of person who would be in your audience. Ask that person to mark their own preferences, just as you did. Now compare your diagram with theirs. That will give you some idea of how close or far apart your expectations might be.

The ten elements

To help you decide on your scores for the ten elements on the wheel, here are some brief explanations of those elements. A simple mnemonic to help you remember them is HAMO IS DEAF.

H is for the Hook

As explained earlier, this does the same job as the headline in a press ad. It is something that you do or say to grab the attention of your audience. After all, it is obvious that you cannot make your pitch without the engaged attention of your listeners. Thanking people for being there is not the best way to open. You can thank them later.

Think about the way films and even TV dramas open these days. They go straight into the action, setting up an incident or an encounter that will determine the way the plot develops, and bring up the titles and cast later. In other words, they open with a hook. Remember, the makers of films and TV dramas know a thing or two about connecting with their audiences. You can use a prop or you can say something unexpected, just as long as you do something more impressive than a seamless move into a PowerPoint slideshow.

The hook is the A in AIDA – it gets Attention.

A is for Audience

Your presentation must be relevant to the audience, to their needs and interests. This means making the effort to find out their concerns, and their business objectives. What anxieties do they have that you can enlarge and relate your message to? Do they have any cultural or social influences that can affect the way they respond to you? Do you have to modify the language you use to connect well with them? What can you find out about their pressure points, their tolerance levels, their attitude to you and your company?

If you do no research and encounter hostility or resistance halfway through your presentation, you may find it hard to recover. It’s better to find out in advance and prepare for it. In the TV series Dragons’ Den, many would-be entrepreneurs are blown away because they do not prepare adequately, and do not anticipate the ‘So what?’ questions that the Dragons like to ask.

M is for M × 3

The 3Ms are Message, Messenger, Method, and are more fully explained in Chapter 9. If you are going to make a presentation, you must have something to say, something you want your audience to hear and act upon. That’s your Message.

The second M is about you, the Messenger. Why is it you giving this presentation, or why do the audience need to hear the message from you? It needs to belong to you, because it expresses your own take on the ideas or information.

The third M stands for Method. This is about technique. You do need to develop the communication skills that enable you to make the most of your message.

O is for Objective

Why are you making the presentation? More importantly, what do you want to achieve, and what do you want to happen at the end of the presentation? It is highly unlikely that you will prepare and deliver a business presentation without some objective in mind, but will it be the right one?

Many a person will say, ‘My objective is to promote my business.’ Is that good enough to tick the box? I have often heard the American motivational speaker, Les Brown, say that the problem is not that people aim too high and miss, but that they aim too low and hit. So it’s really worth taking a close look at what you can achieve with every presentation you make, and make sure you aim high enough.

I is for Interest

The AIDA graph in Chapter 6 clearly indicates the importance of capturing interest and building it to the point of desire. You do that by following a structure, by clarifying the relevance of all your facts, by using stories to make your point, by ensuring that your audience remains engaged. This is about the body of your presentation, and should follow a three-part structure, such as Past/Present/Future or Problem/Cause/Solution. No matter how many things you want to talk about, group them into three streams of argument or reasoning.

S is for Structure

There are two quite separate parts to structure. The first relates to the sequence of the content, as suggested in the previous paragraph. It’s the physical organisation of the content. If it is not structured, if it does not follow a discernible pattern, it could be hard to follow and even harder to recall. A planned structure keeps the presenter on track and helps the audience follow what is being said.

The other part of structure is about the emotional journey. If your objective is to take your audience from where they are to where you want them to be, it will be a process. It is highly unlikely that you could just announce your proposition and get it immediately accepted. You will have to warm up your audience, engage their emotions as well as their minds, and take them gradually up the emotional scale until they say, ‘We’d like to have that.’

That’s the point of Desire – the D in AIDA.

D is for Delivery

Think again about the point made under 3Ms (above) about why it is important to receive the message from you. The presenter makes a difference to the success of the presentation. A vital element in the delivery is conviction. If you believe in your proposition and in its value to your listeners, you should speak about it with conviction and commitment, and that can make all the difference.

Several organisations were involved in a joint venture that came under attack, and they were required to justify their actions. One man organised the defence, with one director from each of the member companies. He himself was going to act as chairman, calling each up in turn.

While rehearsing them, I realised that he was the best presenter of them all, although he had an easygoing, avuncular style. That was because he believed in the rightness of their cause, and in the original project. I switched him to lead presenter and the case was won. Delivery matters.

Emotion and passion

Here again, the emphasis on emotional appeals will vary according to the audience and topic (and also the country). What importance do you give to emotion in the content and passion in the delivery?

A is for Action call

As I said before, you need to drive your presentation towards some action to implement the change that you are aiming to bring about. If you leave it to your listeners to make the decision themselves, you could have a very long wait! If the presentation gains agreement at each step along the way, it is logical to ask for commitment and to tell your listeners what to do next. Don’t hope to play it by ear, plan it.

This is the final A in AIDA.

Facts and figures

There will usually be factual content, supported by evidence. This element will be more important in some presentations than in others, and that will also apply to certain audiences. In general, how important is the factual content in the presentations that you deliver?Essential tip

Essential tip

- Even under different names, the AIDA elements of persuasion work.

There are, of course, other elements that contribute to the success of a presentation, such as:

- Word pictures and stories. Would you illustrate your presentation with stories, and by creating word pictures? Does it help make your message more understandable?

- Oratory. How important is it to use oratorical devices such a repetition, groups of three, and the techniques of Barack Obama and other powerful speakers? (This is developed further a little later in this chapter.)

- Relationship building. Is it necessary, in your view, to consider the presentation a part of the process of developing a relationship, or is it enough just to transmit your message and push for a commitment?

- Respect. Your presentation may be trampling on long-held beliefs, or contradict what someone in the audience may have said, or even run counter to their business practices. Is it necessary to take account of hurt feelings or seniority?

- Humour. Do you believe it is essential to use humour in a business presentation? Are there situations in which you would not use humour? What about telling jokes? Are you the kind of speaker who can get away with it?

Six different kinds of presentation

Although some of the rules apply to all business presentations, we should recognise that there will be differences according to the nature and purpose of the presentation. These are the main kinds:

- New business. This is a sales pitch. It needs to follow the sequence of persuasion, with particular emphasis on addressing the needs of the audience. If treated as a problem-solving presentation, it has a greater chance of success. It should therefore play down the credentials element and trumpet blowing, although testimonials could feature as evidence. The ‘buyer’ or ‘prospect’ should be encouraged to speak, as you cannot solve problems unless they have been stated or confirmed by the other person.

- Persuasive. There are other kinds of persuasive presentations, for example when you are looking for a vote in your favour on a matter of policy or when there is more than one point of view on a central issue. Although the context is competitive (your stance against the rival one) you should avoid criticising the alternative point of view, as that will often alienate those who are still undecided.

Essential tip

- Avoid criticising. It turns people off.

- Motivational. This type of presentation usually depends heavily on the presenter’s charisma, and will therefore not require many slides (if any). This could be a leadership statement, a rallying cry or a call to arms, for example if your company is battling its way out of a recession and you want the team to fall in behind you, or if you are a sales manager calling for an extra push for sales. Often an organisation will bring in an outside speaker who specialises in motivation.

- Entertaining. After-dinner speeches and convention keynotes can be either motivational or entertaining, or both. Their purpose is to lift the spirits and add goodwill to the occasion, and they will therefore be quite informal. Toasts fall into this category, in which the guest of honour, for example, might be teased.

- Ceremonial. These are presentations for special occasions such as retirements, funerals, promotions or the award of some honour. They will be about the personal qualities of the person being remembered or honoured, and be briefer than some of the other kinds of presentation.

- Instructional. These presentations are delivered either as lectures or discussions in which the presenter acts as facilitator. The material (e.g. slides) will be shown and explained, usually one step at a time, and a discussion will follow. The presentation could be to deliver the findings of a research project on which a decision has to be taken, so there will be an element of persuasion, although its pace and timing is likely to be extended.

The importance of the right language

See if you can make mental images for the following words:

- Happiness

- Success

- Hunger

- Achievements

Put them into sentences, and see if that works any better:

- The pursuit of happiness is a noble goal.

- We are looking forward to a successful year.

- Hunger and disease are common in Africa.

- You should be proud of your achievements.

Those are common enough sentences, often used in presentations and in written documents, but what do they do for you? What images do they create in your mind, and do they press your emotional buttons? Try these for size:

- Getting out of bed each morning, greet the day with a welcoming smile on your face.

- Our aim is to double last year’s sales and double the bonus payments too.

- Imagine a child who hasn’t eaten for ten days, grazing on grass.

- Everyone in the company and beyond would like to copy what you did.

The difficulty with abstract words like happiness and success is that they usually do not create mental images that the listener can relate to, and that reduces their impact in a spoken presentation. The text that’s written to be read is not the same as the text that’s written to be said. You can always go back over a written text and think about its meaning. If the spoken text leaves you wondering about its meaning, you’ll find yourself on Track 350, and not listening to the presenter.

Here are a couple more examples of text that’s hard to understand. The first is from a book about getting ahead in business, while the second is from a book on communication skills(!).

- The appeal of the strategies and portfolios approach lies in its ability to wed the underlying strength of strategic planning to the real world limitations on management control in marketing today.

- The implications of identifying underperformance and having individual remedies applied has undertones which could conceivably be interpreted as sinister or threatening to staff.

These are by no means the worst examples of language that you will hear in scripted presentations that are written by people who do not understand the difference between the spoken word and the written text. But they are cumbersome and even difficult to say. In fact you would not speak like that in conversation.

As reported in Chapter 2, Peggy Noonan, speechwriter for US presidents, said, ‘You must be able to say the sentences you write.’ Amen to that.

Essential tip

- The text that’s written to be said is different from the text that’s written to be read.

How skilful orators stir the emotions

A good speaker uses a number of linguistic devices, or figures of speech, to enhance the impact of a speech. The most common are metaphor and hyperbole. The British use metaphor all the time: the boot was on the other foot . . . it was a mountain to climb . . . health warning on the Budget . . . sailing close to the wind . . . pressing people’s buttons . . .

Hyperbole is simply magnification of the truth, exaggeration for the sake of effect. When we describe something as fantastic, immense, incredible and so on, we don’t mean it literally. These powerful words are used to signify something on a grand scale, but also our own reaction or response to them. If we call an event fantastic we mean it affected us as much as a supernatural event.

In addition to these two, there are other figures of speech that can lift a speech out of the ordinary. President Obama, one of the best orators of our time, favours the tricolon, which is the use of three phrases building to a climax.

Obama uses several oratorical devices, including alliteration (e.g. long live liberty, levity and leprechauns), rhyme (while I encourage levity, I more admire brevity) and iambic cadence (I wish I was in Dixie). For the avoidance of doubt, none of these examples is from any of Obama’s speeches. However, here is an example of the tricolon that he did use:

‘If there is anyone out there who still doubts that America is a place where all things are possible; who still wonders if the dream of our founders is alive in our time; who still questions the power of our democracy, tonight is your answer.’

The tricolon was also used by Abraham Lincoln:

‘With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right.’

Obama also used the extended tricolon to great effect. Notice how he combines it here with the ascending structure of ‘not that . . . but this . . . and this above all’:

‘A new dawn of American leadership is at hand.

- To those who would tear this world down – we will defeat you.

- To those who seek peace and security – we support you.

- And to all those who have wondered if America’s beacon still burns as bright – tonight we proved once more that the true strength of our nation comes not from the might of our arms or the scale of our wealth, but from the enduring power of our ideals: democracy, liberty, opportunity, and unyielding hope.’

The first two sentences set the scene for his declaration of principles. It works because it clears the decks by dumping what doesn’t fit, then reinforcing what does, before adding the new. It prepares the listener’s mind for the message. In a business context, you might say something like this:

- To those who think we have fallen behind our competitors, we will surprise you.

- To those who have remained loyal to us, we will reward you.

- And to all who wonder if we are still competitive, we say this – we do not need to chase every new fad or fashion. We are about to announce a development that will amaze you, one that places us at the cutting edge of our industry, but which remains consistent with the values that have lain at the heart of the way we do business.

There are just three more rhetorical devices I’d like to share with you here, although there are others. These are the three you are most likely to use in speeches or presentations, to generate an emotional response. Don’t be put off by their Greek names; they are powerful tools for any presenter:

- anaphora (a-NA-fo-ra);

- epistrophe (e-PIS-tro-fee); and

- symploce (sim-PLO-see). All three relate to the use of tricolons – three statements that build to a climax, as in the examples above.

Anaphora

Repeating a phrase at the beginning of each sentence, e.g. It’s a disaster when a government shoots its own people; it’s a disaster when a business stops trying to be the best and settles for good enough; but it’s a disaster of the greatest magnitude when an individual quits because he or she has been knocked down once too often and doesn’t have the heart to rise again.

Epistrophe

The opposite of anaphora, with the repeated phrase placed at the end of each sentence. One of the best-known examples is in Abraham Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address in which he speaks of government ‘of the people, by the people, for the people’. Another appears in Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians in the King James Bible: ‘When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child.’

Symploce

When the repetition occurs at both the beginning and end of line. A much-quoted example is in Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s book of 1955, Gift from the Sea: ‘Perhaps this is the most important thing for me to take back from beach-living: simply the memory that each cycle of the tide is valid, each cycle of the wave is valid, each cycle of a relationship is valid.’Essential tip

Essential tip

- Use groups of three for elegant emphasis.

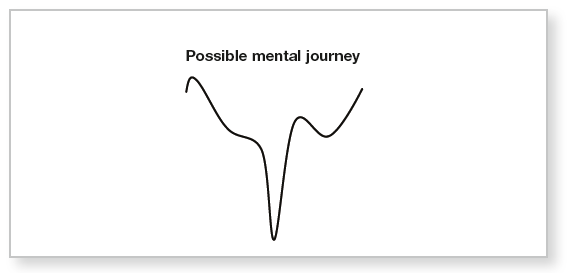

The emotional journey

When you make a speech, your listeners place themselves in a heightened state of expectation. They follow you until you break the thread that connects you, but you do need to be aware of where you are taking them, in case the thread becomes tangled or breaks because you have strayed too far from your theme.

Read the short speech below and think about the succession of images as you are taken from one context to another. Think about where, on the social scale, your mind is taken. It’s a speech to the undergraduates of a law college, on the occasion of the college’s 175th anniversary.

My Lord Mayor, Mr Chairman, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen. It is a rare honour to be invited to address this celebration of your establishment’s 175th anniversary. You have so much glory in your historic past. Your alumni, over the years, have gone on to great achievements, in government, in the law, and in literature. You have produced a Lord Chancellor, several Law Lords, two of them have been Prime Ministers, and one was even more distinguished as Leader of the Opposition.

I was travelling on a train to Newcastle, recently, when I got into conversation with another passenger, and I discovered that he, too, had qualified in this place, just as you are about to do. Something that he said struck a chord in me and I thought I’d share it with you.

He said he felt an obligation to make his legal knowledge available to those who most need it and can least afford it. The two often go hand in hand. Those who live in council estates with low levels of income and limited education often suffer injustice because they do not know where to find, and usually cannot afford, the best legal brains.

No doubt, in your studies, you will have come across such examples, and I would urge you to follow the example of my fellow train passenger and devote a part of your energies and commitment to pro bono work.

At the same time, I would also encourage you to stay close to your families, because as you rise to the top of your profession, as I am sure most of you will, there will be fierce pressures on you, and you will need the support and unconditional love that your families can provide.

This is a privileged place, an amazing building that houses the treasures of law, of knowledge and of art. Your library is one of the best of its kind in the land. And the walls of the principal rooms are graced with some exquisite works of art that the National Gallery would love to have. The main building itself is a work of art, a brilliant example of the best of early nineteenth century architecture. I’m sure it must imbue your bones with its elegance and history.

As you go into your new careers, eyes bright with hope, remember that your graduation does not mark the conclusion of your studies, merely the end of a chapter. There is much more to come, many more chapters to be read, and perhaps a few to be written as you make your mark in the world of law. I wish you all success.

Read it again, but this time draw a diagram to illustrate the mental journey. In the example, the opening is set quite high up the page, because it refers to dignitaries, but the second paragraph takes you to a train travelling to Newcastle. How does that feel, and was the change of scene too quick?

Consider how you feel when the speech refers to the poor and needy and pro bono work. What about the reference to family? Did it take you back to the days of living at home with your parents, perhaps with an untidy bedroom and tensions with siblings?

Whatever the effect on you, plot a diagram of where the speech takes you. Does it work, or did it cause you to lose track?

Remember this exercise, and plot similar diagrams of your own speeches or presentations in the future. You may know what you want to say, but you have to be consistent if you want your audience to follow you. Make it easy for them to understand and accept your Message, get excited about it, and be prepared to take some action as a result.

The next and final chapter is a summary of the book, to enable you to remind yourself of the essentials, and locate the right chapter for any of the points you want to re-read. It also repeats the 30-point checklist, to help you identify where you might still have work to do, going forward.

For further reading I recommend:

Getting Your Point Across, Khan-Panni, How To Books, 2007.

Stand and Deliver: Leave Them Stirred not Shaken, Khan-Panni, Ecademy Press, 2010.

Summary

- The presentation’s ten most important elements

- Six different kinds of presentation

- Language that creates images

- Oratorical devices that press the right buttons

- Mapping the emotional journey