Chapter 7: Optimized lifetimes

The speed and volume with which industrially produced products flow through the fashion system has resulted in their depersonalization. We no longer know the makers, or the source of the materials; they no longer speak of our myths, communities or societies. Our garments have become inanimate objects, mainly providing a means for delivering on commercial goals. Poetic meaning has been reduced in importance in favour of efficiencies of production, and a garment’s aesthetic reflects a bare minimum appeal, developed primarily to secure the initial sale. They are, as Jonathan Chapman calls them, ‘aesthetically impoverished’.8

The limited presence of meaning and empathy in so many commodity fashion products, combined with their low cost and ease of purchase, is a key factor in their being discarded long before they are worn out. To change this requires work on a number of fronts – critically around what influences the lifespan of a garment in material, fashion and emotional terms. Lifespan, or durability, is frequently understood first and foremost as a physical phenomenon: resilient materials and robust construction. But physical durability is a flawed solution in sustainability terms. Often in the fashion sector, a discarded product is not an indicator of poor product quality, but rather of a failed relationship between the product and the wearer.9 And though it may be true that the lack of physical durability in a functional item such as a zip may result in a discarded garment, studies show that 90 per cent of clothing is thrown away long before the end of its useful life. Physically durable products still remain subject to the logic of cyclical consumption directed by ‘Western’ society and culture. And as Jonathan Chapman also notes, ‘when physical materials grossly outlive our desire for them, the result is waste’;10 physical durability becomes a liability rather than an asset when the product is in landfill.

Empathy

True measures of a ‘durable’ product lifetime are best found along emotional and cultural indices – what meaning the garment carries, how it is used, and the behaviour, lifestyle, desires and personal values of the wearer. These empathetic connections are already well explored and understood by companies, since they form the very basis for marketing strategies to sell more product. Using this information not only for financial gain, but also to direct design for emotional attachment to optimize product life for sustainability gains, is quite unfamiliar and uncomfortable territory. It challenges the very core of existing business models.

How we enable products to evoke empathy in an overdeveloped and overabundant material world is a formidable challenge. The fast-paced and visually noisy marketplace depletes the psychic attention of the shopper; elements that might signal emotional attachment to a garment, as quiet as they often are, can easily be drowned out by the competition for a shopper’s attention. Indeed, designer Christina Kim of Dosa acknowledges and circumvents this problem by showing her ‘slow fashion’ line in her own gallery space in downtown Los Angeles, by appointment only. Here, viewers can take time to savour the unique qualities of each piece and absorb the whole philosophy of the designer in her space (see page 177). Moreover, empathy often evolves through reflection and acquired narratives, which build slowly and over time, after the initial purchase is secured – that is, beyond the designer’s direct influence. Enabling these narratives to be captured is therefore a delicate dance, for intent and meaning are subject to countless personal interpretations based on both past associations and the experiences of the wearer – a memory, a significant event or a rite of passage – and as such, responses can be quite unpredictable from person to person.

Durability’s physical and emotional attributes

Yet there are some well-accepted physical product attributes that consistently delight our sensibilities. The ‘faded bloom’ of denim, for example, acquires an increasingly desirable character over time, capturing the user’s particular patterns of wear and tear and continuously building on its emotional content. And the feel of cashmere never fails to deliver and redeliver a comforting and warm sense of well-being to any wearer. Besides these tactile routes, emotional content can also be achieved through the skilful treatment of something as simple as a label. The Californian company ZoZa, for example, sewed thoughtful messages such as ‘Don’t be tense. Be present’ in unusual places inside their garments, which created immediate delight upon discovery, and a lasting appreciation that the designer was emotionally engaged when creating.

Additional examples, where the emotional engagement of the designer is apparent and the same is enabled in the user, could be explored by exploiting the varying light- and wash-fastness properties of natural dyes and layering the fabrics accordingly in a garment so that patterns are revealed and evolve over years of use; conversely, over-printing the same garment while integrating resist areas to provide a ‘window’ on its previous state would capture the past while creating a new pattern and allowing more complex patterning to evolve into the future. These poetic touches create space for moments of clarity and shed a slanted light on different ways to create and experience fashion.

Understanding the various aspects of durability – emotional, trend-based and physical – in the context of an individual wearer of clothes generates a place at which resources and meaning can be optimally satisfied. Yet, if the ultimate goal of optimized lifetimes is to slow the flow of natural resources through the fashion system, then designing more emotionally durable products may be as limited a strategy as physical durability. For the fastest-growing real-estate sector in the US is self-storage, now a $50 billion industry, and the majority of items contained in these units is middle-class ‘stuff’. This state of affairs exists even though families in the US are half the size they were in the 1950s, and houses twice as large. Just as reducing the embodied energy in one garment does not guarantee absolute energy reductions as the overall business grows in size, so optimizing the lifetime of one item alone does not necessarily guarantee net reductions in resource consumption. Achieving ‘absolute optimized lifetimes’ through fundamental shifts in culture, social behaviour and business practice remains the imperative.

But despite their limitations, what all of the above concepts do provide is an emotional feedback loop for the wearer, where we can reassess our relationship to each piece, contemplate notions of use, ownership and need, and take account of the stocks and flows of things passing through our lives and recalibrate the metabolism of our wardrobes.

Optimized lifetimes

The notion of optimized lifetimes as a category of sustainability in fashion has invited a number of approaches and explorations, each iteration reflecting deeper knowledge and more integrated responses to sustainability. We have seen optimized lifetimes evolve from simple beginnings expressed in the materiality of the product (as physically robust fabric and construction; and in Cradle-to-Cradle-inspired recycled and biodegradable fabrics). We have seen concepts outperform industry’s ability to change (as with Patagonia’s ‘Sugar and Spice’ shoe, designed to be disassembled and recycled, which fell short of its goal because of a lack of industry infrastructure), and conversely we have seen concepts hit the mark (as in Avelle’s bag-leasing service, see page 103), where product characteristics imbue both a short-term emotional quality to one consumer, and a long-lasting physical quality to support continuous recirculation and extended use by many.

A growing number of research projects are contributing to our understanding of how to make garments appropriately durable. The ToTEM (Tales of Things and Electronic Memory) project investigates the potential to associate people’s personal stories with specific objects through the use of Quick Response (QR) codes and RFID tags, thereby enabling others to read them and gain an insight into an item’s significance. And the clothing-specific project WORN_RELICS© provides a unique space where the lifetime history and future of clothing can be collected and archived. Participants apply for a password provided by a coded label that allows them to register an item and create a profile of it on the Worn Relics web site. Entries may be updated and many of them follow the continuing life or journey of the garment. The archives not only reveal the attachment between the product and the wearer, but a whole web of associated relationships, uses, feelings and memories that inevitably become linked with an often-worn garment.

Multiple approaches to durability

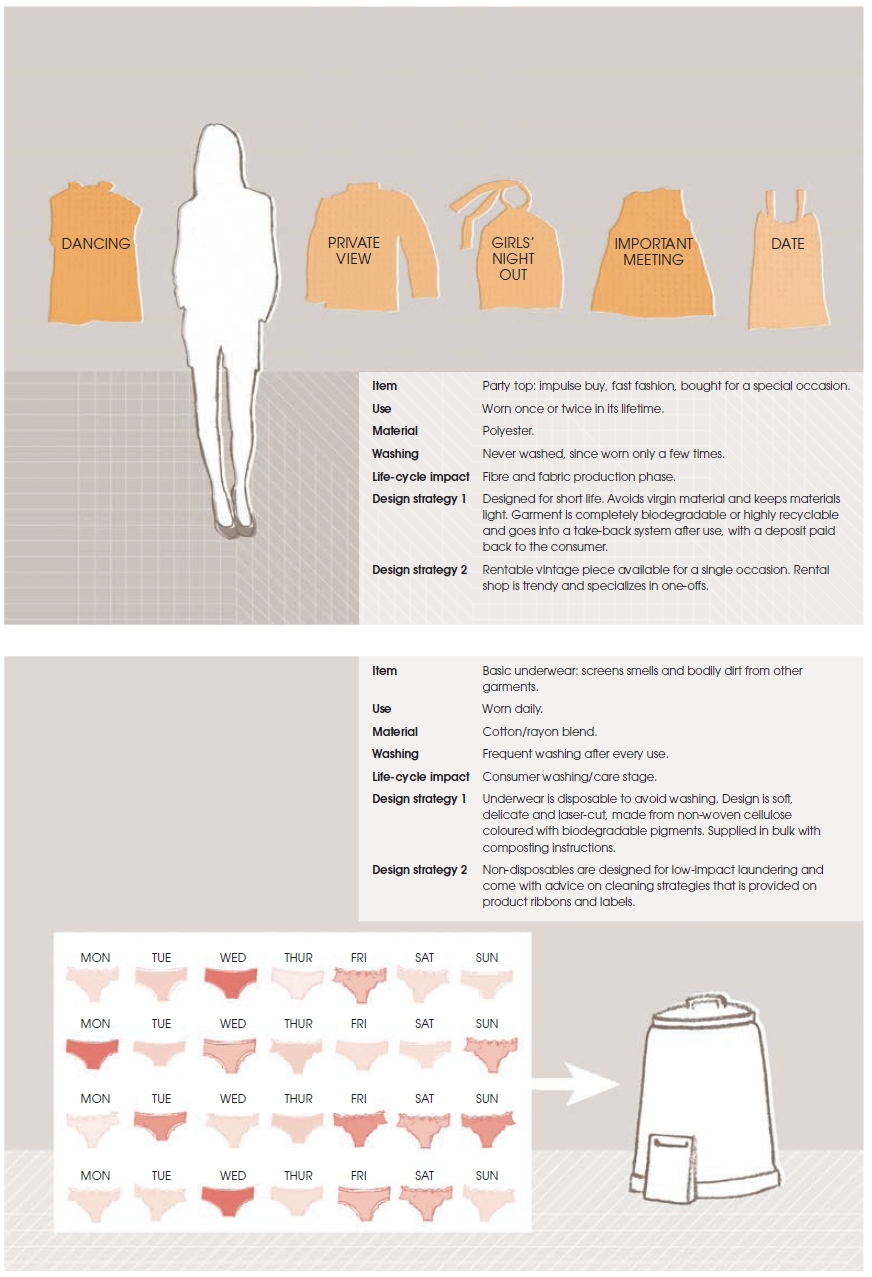

One means of imagining beyond existing frameworks is through ‘future scenarios’, where explorations are carried out along a given set of criteria based on well-researched socio-cultural and ethnographic tendencies, and pushed as far as possible to gain insights into what might happen decades in the future. The 2004 Lifetimes project by Kate Fletcher and Mathilda Tham presents a nuanced exploration of clothing and the potential for designing more resourceful garments by considering speed and time. This involved researching products across a number of indices including extended life, durability, materials, use and services. The goal of the project was to create scenarios for more resourceful consumption for specific garments, as summarized in the table on pages 90–91.

Metabolism of a wardrobe

Scenarios such as those developed in the Lifetimes project help us imagine future possibilities that involve minimal financial investment in infrastructure or prototype development, and enable us to reason through a host of influences to create a platform from which we can imagine logical next steps. Given the scenarios developed in Lifetimes, it is not too far a stretch to imagine, for example, a time when everyone knows the ‘metabolism’ of their wardrobe and has the ability to adjust it. Rather than being mere receptacles periodically purged to create more space, wardrobes become places of ‘dynamic equilibrium’; clothes are reworked, shared and reused without constantly requiring a flow of new goods and resources. Here shopping is no longer at the centre of the fashion experience but is simply one among many aspects incorporating also the creative energies of individuals as they consider the optimum lifetime of each piece and refresh their wardrobes and themselves in new ways.

Current (top) and future (below) wardrobe metabolisms indicating many options for slowing personal material flows.11