Chapter 14: Engaged

‘No humans or other living beings can survive without multiple interconnections with other organisms.’

Ernest Callenbach70

At the heart of sustainability is an experience of the connectedness of things; a lived understanding of the countless interrelationships that link material, socio-cultural and economic systems with nature. These connections operate at different scales and with different spheres of influence, some on a direct local level and others globally. Openness to these relationships is a key precursor for change as it demonstrates the dynamic effect of each part on every other. Put simply, when working with sustainability ideas and practices, nothing exists in isolation.

Such an approach contrasts sharply with most fashion products on offer today, which can be seen to epitomize value-free expression and equip us to appear in a world that has little or nothing to do with the Earth, the health of its soil or its people. Such a world is abstract and remote and has a tenuous relationship with the reality of how fashion is made, used and discarded. Robert Farrell has described this as a ‘world of ideas’;71 an imaginary place where the consequences of actions need not be felt, where almost anything is possible, where there are few limits. Yet our reality is different to this: our planet plainly does have limits. Many of the ecological systems on Earth are closed systems of finite capacity, and fashion is as subject to them as anything else is. Restoring the relationship between fashion and the social and ecological systems that support it requires transformation of the remote, abstract ‘world’ that has so far shaped conventional industry into something more direct and connected.

Lynda Grose’s yellow vintage dress with embroidery by Nathalie Chanin makes narratives of wear and relationships between friends visible.

Sustainability is based on action

Much of the shift towards interconnectedness implied by sustainability is predicated on us being active – as individuals (in our roles as designers and also as consumers) and collectively as a society. This means engaging with and enquiring about material flows, design processes, business models, social questions, ecosystems and so on as an intrinsic part of life and, by extension, of the fashion experience. However, for many consumers of fashion, it is passivity rather than activity that characterizes their experience of buying and dressing in clothes. The products on sale in the high street are largely homogenous and this lack of choice erodes individual expression, dulling consumers’ imagination and limiting their confidence about what clothes can be. This lack of self-belief spills over into hesitance to make, alter and personalize pieces. Consumers find themselves with little choice but to be on the receiving end of the fashion industry’s ‘product’. Here they choose between styles created for them by designers, manufactured by distant workers, selected for them by buyers, presented to them by marketers. They then wear these pieces in combinations directed by stylists and magazine editors and replace them regularly as trends manufactured by forecasters change. Select information about each garment flows one way down the supply chain from producer to consumer with little or no opportunity to interrupt this flow and ask questions. The effect is to create a physical and emotional void between those who wear the garment and those actors, and environments, who produce it. This leads to an absence of connection on a global scale, underscored by the growing corporate practices of brand loyalty creation and offshore production; legitimized by the trading rules of global institutions such as the IMF and the WTO; and reinforced by the established hierarchies of the fashion industry elite, who benefit from the status quo and the passive state of most consumers.

Innovating to bring change in the form of a new engagement with fashion is highly politically charged. It challenges the dominance of the growth model – large-scale, globalized production, non-transparent supply chains, the flow of large volumes of similar garments, and the mystique of the fashion creation process. Yet the benefits it promises are linked to the possibility of recreating counter-flows where consumers do not just follow but can perhaps also lead, and thereby participate in fashion in a more co-operative, healthy, active relationship with the whole.

Co-design

Co-design, the practice of designing with others, involves the collaborative design of products together with the people who will use them. At a fundamental level, co-design contests the economic growth-driven logic of most design activities today and offers an alternative based on different imperatives such as greater democracy, improved empowerment and less domination, through practices such as inclusiveness, co-operative processes and participative action. Its premise is that those who use a product are entitled to have a say in determining how it is designed. And that when stakeholders and their interests shape and contribute to the design process, the quality of a design increases.

Designing with users

Over the last decade, the practice of designing with users rather than for them has been on the rise, no doubt influenced by growing interest in the social and political dimensions of design and by, for example, the role of the Internet in opening up new design opportunities. Co-design’s political and social potential springs from its influence over who in society holds power, who controls knowledge and who makes decisions. Some Internet-based co-design initiatives such as Linux software and the online encyclopedia Wikipedia exemplify this set of changed relationships. These initiatives, created by a widely distributed network of volunteer creator-users, make the knowledge within the product available for the common good. Those involved share the work and also share the benefits.

Co-design’s aim, to ‘reduce top-down mechanisms to a minimum and… to share practice between a multiplicity of participants on as equal terms as possible’,72 greatly disrupts traditional fashion hierarchies, where most power is conferred to those at the top of the tree. Elite designers, high-street retailers and global brands cement and even augment their positions by protecting their concepts and products. Select ‘auteurs’ hold knowledge in a secretive system closed to outsiders. Information flows one way down the hierarchy from top to bottom, as decisions about design direction, finish, fabric and cost are handed down to producers, supply chains and consumers. Maintaining the security and exclusivity of the knowledge system keeps the fashion establishment in power and in the money. For without access to knowledge and associated skills, in both the material and symbolic aspects of fashion, users cannot do-it-themselves.

Co-designer Otto von Busch invokes the ‘Cathedral and Bazaar’ metaphor first developed by online open-source pioneer Eric S. Raymond, to contrast the different social organization of traditional and co-designed fashion. The top-down, stratified and closed model of fashion is the Cathedral, ‘where strict chains of command are built into the structure itself’.73 The Bazaar, by contrast, is co-designed fashion, ‘a free buzzing market where everyone is talking simultaneously. It is chaotic yet somehow organized, like a street market or anthill.’74 The Bazaar’s (or co-design’s) organization is flat, or heterarchical, and all elements are linked or networked.

Collective understanding

In co-design, the design process is turned out on itself. Here, the concern is less about producing rarefied objects and more with building capacity in the user population. It stresses collective understanding, designing and doing – and this expanding knowledge and experience is not just reserved for the amateur designer, but influences the professional one too. Sociologist Elizabeth Shove and colleagues put it in these terms: ‘rather than a design(er)-led process in which products are imbued with values for consumers to discover and respond to, proponents [of co-design] … argue that the traffic flows both ways.’75 It is in this two-way flow of ‘traffic’ that the co-designer dwells, working in multipart roles as facilitator, catalyst and encourager, both learning from and teaching other actors in the process.

Different approaches to co-design

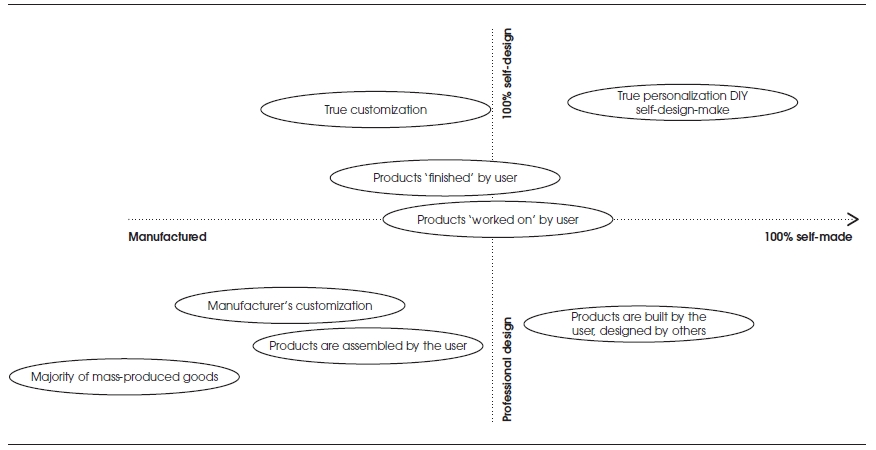

Co-design often emerges from the grass roots and builds on processes and appetites that already exist. In his book Design Activism, Alastair Fuad-Luke explores a spectrum of design and making activity (see fig. 11).76 While established industry practices tend to fall in the lower left quadrant of the chart, between the axes of manufactured production and professional design, new activities and interests are beginning to populate other areas. Home dressmaking, for example, has experienced considerable growth in recent years as people begin to self-design and make, largely as a low-cost alternative to buying clothing in recession-hit times. And the development of modular products (see page 80), where a series of panel pieces can be built into a variety of garments, leaving space for the user to refashion how a garment is made, also marks out a different role for designing and making.

Antiform Industries works within the Hyde Park community in Leeds, UK, to create fashion co-operatively.77 Tapping into pre-existing sewing, repair, craft and embellishment skills and offering training where skills are in short supply, Antiform has facilitated the creation of an eight-piece collection with 64 local people (beaders, knitters, artists, seamstresses and volunteers) sold in the Leeds districts of Hyde Park, Woodhouse and Chapeltown. All materials for the collection are waste clothing gathered in the area from free monthly exchange events, which bring an influx of materials and people into the project. The symbiotic relationship between the resulting collection and the materials exchange is key to the project’s development, allowing local residents to get involved in many different levels of the project, creating a new system for local fashion.

FIG. 11 WAYS OF DESIGNING AND MAKING.78

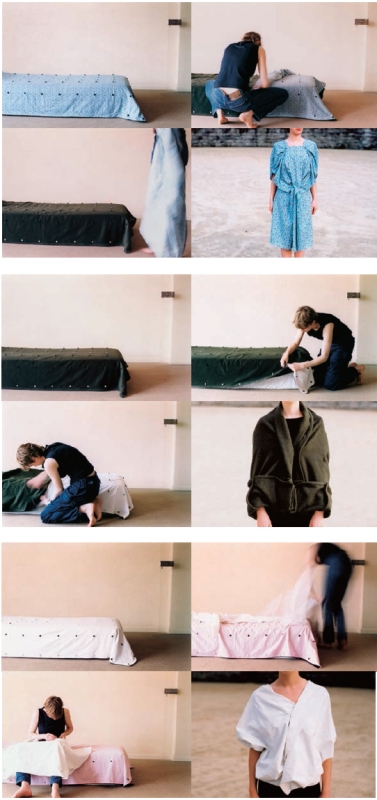

In contrast, Self-Couture by Diane Steverlynck is a multifunction piece, exploring a different way of designing and making.79 Both garment and bedding, the piece is composed of two to five layers of fabric in different materials, chosen for their specific character between bedding and clothing. Each layer is evenly perforated with buttonholes and double buttons that can transform every layer into a sleeping bag, a single or double sheet, a winter or summer blanket, a dress, a blouse, a jacket or a skirt. The project designs with the user, offering the prospect of many changed forms and uses from a simple piece of fabric.

Active craft

Craft is hands-on, resource-based and practical. It has a visceral connection with materials and the way they are shaped into forms for display or use. It involves the actual doing of something rather than merely the experience of being done to – that is, the practice (in the case of fashion) of stitching, knitting, cutting, draping, folding and joining to make fabric into garment.

Leeds-based Antiform Industries designs and produces garments in a collaborative, community process with the people who will wear them.

Also essential to craft – and to crafting well – is experience: long hours working and reworking the same technique. Crafting is a slow activity, with skills maturing over time as the crafter reflects, thinks deeply and constantly tests the limits of his or her activity. In his book The Craftsman, Richard Sennett describes craftsmanship as ‘the desire to do a job well for its own sake’.80 This motivation brings the powerful promise of emotional rewards; it anchors people in material reality and allows them to take pride in their work.81 For all of these reasons – for its connection to resources, for its active, hands-on quality, for the value it places on lived, grounded experience and emotional satisfaction – craft supports many sustainability values.

Self-couture garments/bedding by Diane Steverlynck.

Craft is political and democratic

There are other reasons why the relationship between craft and clothing is a rich seam in sustainability terms. Highly developed craft skills can be seen to support democratic ideals, for their potential is distributed widely among us all rather than attributed only to those with wealth or privilege. Crafting garments employs hands in combination with materials and machines. Here it is what you do – that is, technique, honed by years of experience – not who you are or how much technology you can access, that plays a defining role. Further, craft production can be seen to convey a sense of restraint in consumption, a speed limit and volume cap, for after all you can only consume as much, and as fast, as the craftsperson can produce. Craft can, perhaps covertly, even imply further restrictions. It can suggest that we produce just enough for our own personal consumption (and in so doing opt out of the corporate, industrial model); or produce as a protest against, say, poor treatment of garment workers and degrading environmental quality, because it allows us to control more closely production conditions and material provenance.

In all of these contexts, craft is clearly political. It is an expression of production values, power relations, decision-making and pragmatism. Its sharp political edge is felt perhaps most distinctly in needlecraft’s changed role in women’s lives over the past 50 years. As recently as two generations ago, knitting, embroidery and dressmaking were part of women’s domestic duties and household obligations, keeping females’ ‘idle hands busy’. By contrast, in the past decade, vastly different socio-cultural, labour and material conditions have seen needlecraft reclaimed by women as liberating feminist action rather than as subjugating work. It has been recovered as a practical, satisfying, expressive and creative act in and of itself. It is now sometimes referred to as part of the ‘new domesticity’, where meaning is brought to a society dominated by mass-production and ready-made products and with decreasing space and time for hobbies.

Craftivism

Richard Sennett describes the meaning and contribution of craft to society as, ‘the special human condition of being engaged’, and something that reflects a satisfying process rather than the action of simply getting things to work.82 He continues: ‘At its higher reaches technique is no longer a mechanical activity; people can feel fully and think deeply about what they are doing once they do it well.’ Thus craftsmanship fuses head and hand, bringing thought to life through action. At the level of expert, when feelings and thoughts are maximally open, ethical, political and environmental questions appear uncloaked. It is in this context that the term ‘craftivism’ has evolved, a neologism naming craft as a change agent in material, political and social culture. It describes a role for practical work to participate in and shape negotiations about consumerism, industrial production, equality, environmental conditions, individuality and materialism, among other issues. It blends political questions and practical action.

Craftivism is an area of rapidly growing interest, as evidenced by Craft Lab, a new creative hub with emphasis on critical making set up at California College of Arts,83 and the highly popular ‘Craftwerk 2.0: New household tactics for popular crafts’ exhibition in Sweden.84 Irrespective of academic interest in craft as activism, its power as an agent of change emerges from widespread public involvement, where for example users engage in the skilful process of constructing pieces that are more than the sum of their parts. To work in this way requires users to have such skills as self-confidence, reflective awareness, practical knowledge and an ability to operate in modes of social organization different from the status quo. Practical technique hewn from experience is used to influence a social and economic agenda in the ways of quality over quantity, active making over passive consuming, empowerment over domination, and rebellion over acceptance. Such practices can help users engage with fashion on a level deeper than as consumers, and help connect with materials, skills and language necessary to create both physical objects and a brave new world of sustainability ideas.

The short jacket with finger-knitted extensions by Elisheva Cohen-Fried starts to reintroduce craft into a fast-paced modern lifestyle.

Elisheva Cohen-Fried’s short jacket is designed with finger-knitted extensions that the user adds to after buying the garment. Loops are strategically placed on the garment to capture the lengthening knitted pieces, and creativity is enabled through the simplest of craft techniques: finger knitting. The jacket invites the wearer to be more than a consumer of commercial products, engaging her as a co-designer, adding craft and personality and gaining making skills in the process. Moreover, in a world of de-skilled wearers, this concept allows for the creative contribution to be easily accomplished without specialized tools and even in our fast-paced modern lifestyles: on a bus or a train, in a taxi, during a flight…

Hacking

In line with the intensely political nature of participatory design actions, hacking and fashion production can enhance the promise of engagement with a garment by challenging the control and power of the fashion system. A hacked garment is one that may provide a clever or quick fix to a particular issue such as fit, or hacking may involve the modification of a piece, its production process or its advertising and semiotics to subvert it for political gain, or more practically, to give the user access to features that were otherwise unavailable.

Direct action

Hacking in fashion borrows heavily from the language and practice of computer hackers, who open up commonly available consumer electronics, modify software and parody and sabotage web sites, among many other activities. In its most positive forms, computer hacking explores how electronic direct action might work towards (technological) change by combining programming skills with critical thinking. Though it is also associated with more destructive acts across a wide span of political ideals and issues, including those that attempt maliciously to undermine individual, corporate and state security, in the main, electronic hacking is seen as activity that is productive rather than destructive. It needs the system that is being hacked to continue working in order for the hack to be a success. Its goal is not to damage a system and switch it off, but to build something extra in that system into which it plugs: ‘hacking is the mastery of a system but usually not with ill intent. While it is true that every hack needs a crack, a central aspect of hacking (unlike in cracking and breaking) is building and constructive modification.’85

Keeping the power on

In sustainability, the model for understanding and organizing society is ecological and based on networks. Likewise, most participatory and co-design activities are best understood in terms of networked flat structures. Networked forms propose alternative structures for practice and it is in altering and tuning networks and rerouting the energies of the system that hackers have made their home. Otto von Busch, the leading instigator of work on fashion hacking, describes one role for fashion hackers: ‘Diktats from Paris, London, Tokyo, Milan or New York can be short-circuited, tuned and repurposed… Not opposing the inherent magic of fashion, but re-circuiting its flows and its channels. Keeping the power on.’86 This implies action from individuals, changing how they wear, modify and put together pieces but also more than this: it can lead to modified communities and changes in the ways fashion is communicated. For when a system is hacked, it is made ‘to do new things by explicitly using the existing forces and infrastructure within the system for changing it’.87 Black Spot sneakers, for example, invites every purchaser to contribute ideas on product marketing strategy, and designs a blank space on the shoe specifically to accommodate a logo developed by each wearer, thereby using existing and accepted mechanisms to reverse the usual flow of power. Here the implications stretch beyond changes to physical products to include also people and behaviour.

Hacking is both process- and outcome-focused; the activity itself has a finesse described by the journalist Steven Levy thus: ‘the feat must be imbued with innovation, style and technical virtuosity.’88 This brings hacking firmly into the territory of design and, more specifically, co-design actions, which share a similar concern with the technique or process. Hacking activities themselves are potentially wide-ranging and, according to social researcher Anne Galloway, may involve:89

- access to technology and knowledge about it (transparency);

- empowering users;

- decentralizing control;

- creating beauty and exceeding limitations.

The process and products of ‘hacking’ the manufacturing process of hand-made shoes at the Dale Sko shoe factory in Norway.

Hacking in a fashion context

The challenge in hacking, as in most forms of engaged practice, is to create something beyond the original design intentions; this can be product-based, process-focused, or system-wide. This helps differentiate hacking from, say, customization, which largely works within the original design’s framework. In his PhD thesis, Otto von Busch gives form to what some of these might mean in fashion:

It could be anything from the product–service relationships in the form of barbershop-like recycling boutiques, to offering restyling help and infrastructure for drop-in updating of clothes. It could be workshops that engage in secondary school craft curricula. It could be free DIY books created in collaboration with the greatest haute couture designers. It could be projects exploring the full width of user engagement, from various forms of Lego-like kits to shared workshops for co-production inside fashion stores. It could be new forms of Swap-O-Rama-Ramas where whole new scenes are formed and shared and that intersect both a wide range of lifestyles and high-quality production.90

The hacking project at the Dale Sko shoe factory in Norway was a three-day experiment in 2006 that explored the forces at play between globalized fashion and small-scale local production of shoes using collaborative design approaches. The project brought Norwegian fashion designers into a small hundred-year-old shoe factory, reduced by the pressures of a globalized market to a small unit creating a line of hand-made shoes. The aim was to tinker and manipulate (hack) the flows and functions of design and production by allowing designers better to understand the limits and potential of production and the shoe producers. This provided greater access to the creative and business potential sparked by creating shoes and remixing existing models with new materials and processes. The outcome was a collection of shoes and a newly invigorated business approach for Dale Sko shoe factory, where collaboration between some designers involved in the original hack and the factory is continuing. Here both the fashion system and shoe production are firmly redirected at the same time as small-scale creation and tradition.