CASE STUDY 12

Learn by Numbers

Keith Boyfield

As a topic, international accounting standards are not necessarily guaranteed to send a shiver of excitement down people's spines. But this indifference may soon change because UK public companies have been required – as from 1 January 2005 – to comply with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

The new accounting standards are likely to have a profound effect on the way in which utilities state their financial results. As this involves money along with a potential volatility in share prices, investors are likely to give it their rapt attention. Yet it is important to highlight the fact that the implications of IFRS will vary between utilities depending on their business activities.

Why introduce IFRS? In part, like Sarbanes-Oxley, it is a reaction to the succession of corporate scandals that have surfaced in recent years. Regulators believe that the more rigorous rules established under IFRS will curb potential fraudsters, limit any damage that might be associated with maverick management methods and allow companies less flexibility to manage how they present their financing activities.

Experience suggests, nonetheless, that fraudsters will always be with us and IFRS may simply encourage some managers to cut corners in new and innovative ways. But overall, the utilities sector across Europe has a good record when it comes to observing accounting standards.

Another of the key goals linked to IFRS is the desire to enable investors to compare in a more accurate and transparent manner the operational and financial performance of companies across Europe, particularly where these companies operate in the same sector. Furthermore, IFRS is closer to US GAAP than the old national accounting standards, making transatlantic comparisons easier, too. As the utilities sector in the European Union continues to consolidate, this objective is close to the hearts of institutional investors.

IFRS introduces a host of changes – which is good news for accountants – but relatively few will fundamentally change the stated profits or assets of most utilities.

One of the most important new standards for the utilities sector as a whole is the new “financial instruments” standard (IAS 39), which will require companies to “mark to market” many commodity contracts. To mark to market is to calculate the value of a financial instrument at current market rates. Furthermore, any changes in marked-to-market (MTM) values may need to be stated in the profit and loss account, which could trigger considerable earnings volatility. This is because the whole change in value for a long-term contract will flow through the earnings statement every year.

Commenting on this likely trend, Iain Smedley, an executive director with Morgan Stanley's investment banking division based in London, says: “The market will tend to look at ‘pre volatility’ numbers when assessing financial performance and multiples such as price/earnings ratios.”

“At the same time, the greater disclosure of details required under IFRS may well throw up a raft of interesting facts – including issues relating to pension funding, financial leases and commodity contracts. This could well have a significant impact on share price, or at the very least highlight areas on which investors should focus.”

There is still some uncertainty about exactly what commodity and derivative contract structures count as “hedges”, and can therefore be termed “IFRS friendly”, because they are unlikely to cause earnings volatility. Inflation risk hedging is particularly significant to regulated water and electricity networks companies, where both the regulatory base of the assets and the revenues earned from those assets are indexed to inflation. In the interests of optimal risk management, a clutch of utilities have sought to issue inflation-linked financing or achieve the same risk management goal using derivatives.

But a note of caution should be sounded. The interpretation of IFRS in1 these areas is as yet unclear, so many accountants are reluctant to support the use of derivatives to hedge against inflation risks. “Companies must avoid the paradoxical trap of being exposed to real economic risks just because they are trying to follow an ‘accounting safe’ approach,” says Smedley.

James Leigh, an energy and utilities partner at Deloitte makes a similar point: “As the complex IAS 39 rules become better understood by energy and utilities companies, the areas of debate become narrower and arguably more marginal. While these areas are important, companies also need to focus on explaining the impact of new standards to their investors and, in particular, how their trading and hedging strategies drive their commodity accounting. However, this debate should not be limited to IAS 39, as a number of energy and utilities companies will also suffer the erosion of net assets from changes to pension, deferred tax and possibly fixed asset accounting. Nobody in the energy and utilities sector finds the introduction of IFRS easy.”

Sir Roy Gardner, chief executive of Centrica, reckons there are four specific areas linked to the introduction of IFRS that are particularly relevant to his company. First are “mark-to-market energy contracts that are not for own use or do not qualify as hedges under IAS 39”. In his review for the latest financial year, he noted that the “form and timing of IAS 39 is still uncertain”. Alas, there is still some uncertainty almost 12 months later.

Second, he pointed out there was a need to “confirm a final, industry treatment for Petroleum Revenue Tax [PRT]”. In this context, “there is uncertainty over whether PRT should be treated as income tax or a production cost which impacts the method of calculation”.

Third, Gardner notes that IFRS will demand that companies record any pension deficit, net of deferred tax, on the balance sheet under the IAS 19 rule. This standard has been the subject of technical revision but the latest position appears to be that companies will be able to use the FRS 17 model as well as what is referred to in jargon as the corridor method, with actuarial adjustments recognised in equity.

Fourth, IFRS will require publicly quoted companies to subject goodwill to an annual impairment test rather than an amortisation charge, as happened previously.

In a recent presentation to investors, Phil Bentley, Centrica's group finance director, observed that: “It is important to note that IFRS has no impact on our business strategy, nor on the cash flows generated by the business, and it does not change the underlying drivers of value of Centrica's business model.” Indeed, Bentley argues that cash generation will continue to be one of the key performance measures for the company. In a separate presentation to investors, Simon Lowth, Scottish Power's director of finance and strategy, has made precisely the same point.

No doubt both are trying to impress experienced analysts such as Catherina Saponar, now of Bank of Montreal. For her part, Saponar points out that “cash flow remains one of the most important measures for utility companies”. Indeed, she adds, “IFRS may lead to an ever increased focus on cashbased measures”.

Bentley recognises that the commodity mark-to-market requirement is particularly significant for Centrica's business (in comparison, say, with a company like National Grid Transco). Specifically, Bentley acknowledges, “the requirement to mark to market more of our commodity transactions requires the initial recognition of unrealised profits and losses and introduces volatility in the Group's reported profits”.

The adoption of the new IFRS rules will have an even more profound impact on the future financial results reported by National Grid Transco. In overall terms, the new accounting standards are expected to lead to an increase in operating profit, pre-tax profit and earning per share. Yet the treatment of net assets is likely to lead to a lower figure.

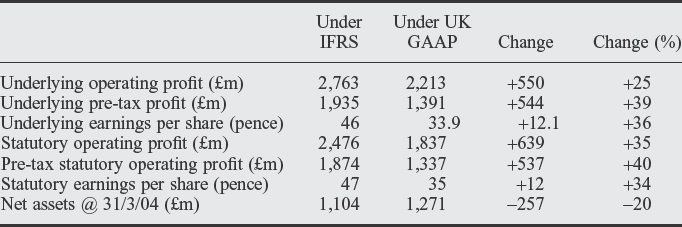

Table C12.1 illustrates the impact that the adoption of IFRS would have had on National Grid Transco's consolidated profit and loss account and net assets for the year ended 31 March 2004.

Table C12.1 The effect of IFRS on National Grid Transco's results (2004)

One of the drivers behind IFRS is the extensive use of fair value accounting. But this has proved a controversial initiative because this can lead to a host of practical difficulties, most notably the increased volatility that goes hand in hand with such accounting techniques.

BAA, the airport operator that runs Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted, has decided to stop issuing quarterly results because the company feels it is impractical to revalue its £8.6 billion property portfolio so often. It is the first major publicly quoted company to adopt such a strategy, specifically to avoid IFRS reporting standards, but not necessarily the last. What is particularly significant is that BAA only opted to make this move after extensive consultation with its major institutional shareholders.

From an investor's point of view, some of the more sophisticated institutions and fund managers may use the new IFRS accounting standards as a hook on which to conduct speculative activity in the hope of significant share movement. For the most part, such wholesale investors will take IFRS in their stride. But individual investors, some of whom may have acquired their shareholdings at the time of privatisation, may find the new accountancy standards confusing.

Probably the best advice for such investors is to consult company websites – most utilities have been at pains to explain the practical implications of the new IFRS rules. And it would pay individual investors to examine the detailed research prepared by equity analysts on this topic. Again, some of this can be downloaded free of charge from a number of financial websites.

One final point is worth mentioning. Charlie McCreevy, Ireland's former finance minister and now Commissioner for the internal market in the European Commission, is taking a close interest in the implementation of IFRS standards. If investors have any complaints about the impact of these new rules, he would be a good person to contact. After all, he is a chartered accountant by profession, so at least he should be able to understand the numbers.

Reproduced from Utility Week (17 June 2005), by permission of Keith Boyfield.