Chapter 8

Questioning in Your Personal Life

Judge a man by his questions rather than his answers.

—Voltaire

What can good questioning do to enhance your personal life?

![]() Boost your child’s cognitive abilities and verbal skills.

Boost your child’s cognitive abilities and verbal skills.

![]() Help you ease into social situations.

Help you ease into social situations.

![]() Find winners in the dating scene.

Find winners in the dating scene.

![]() Ensure you don’t come across as a self-centered jerk at a party.

Ensure you don’t come across as a self-centered jerk at a party.

![]() Convey compassion to someone in pain.

Convey compassion to someone in pain.

![]() Save you money.

Save you money.

![]() Make life more pleasant in general.

Make life more pleasant in general.

In this list of benefits, some are intuitive and some merit discussion. One that doesn’t warrant discussion, but is backed by a short story that makes the point, is “save you money.” When my children were in elementary school, our family went back-to-school shopping and my wife and I felt sticker shock at the price of clothes for little girls. I asked the cashier, “When does the half-price sale start?” I was joking. She said, “Thursday. But I guess there’s no harm in giving you the deal today.”

That was one of my better questions.

Using questions well in your personal life has a great deal to do with spontaneous opportunities to interact with people, such as my experience in the store. If you’re walking through a mall and you see someone struggling with packages, that’s a perfect occasion for a friendly requestion: “May I give you a hand with that?” In that context, your asking the question could be the most wonderful thing that happened to that person all day. Questions in our personal life shouldn’t be tools of interrogation, but rather tools of connection.

It’s important to note also that people don’t pose the same question identically, nor do they respond to identical questions in the same manner. Our different personality types make some of us more inclined to question comfortably and well, and others to be less comfortable or adept at asking questions. Similarly, our different personality types give some of us an advantage in evading a question or outright lying, whereas other types find deception very stress-inducing.

A wonderful Website called StoryCorps features great questions in multiple categories to help people get a conversation going. It even includes a “question generator,” which enables the user to create a set of customized questions that reflect a particular need, such as conversing with someone who is going through a difficult time in life. The category of “great questions for anyone” features a number of well-structured questions that naturally evoke a narrative response. A few of them are:

![]() What was the happiest moment of your life? The saddest?

What was the happiest moment of your life? The saddest?

![]() Who has been the biggest influence on your life? What lessons did that person teach you?

Who has been the biggest influence on your life? What lessons did that person teach you?

![]() Who has been the kindest to you in your life?

Who has been the kindest to you in your life?

![]() What are the most important lessons you’ve learned in life?

What are the most important lessons you’ve learned in life?

![]() What is your earliest memory?

What is your earliest memory?

![]() What is your favorite memory of me?

What is your favorite memory of me?

![]() What are the funniest or most embarrassing stories your family tells about you?

What are the funniest or most embarrassing stories your family tells about you?

![]() If you could hold on to just one memory from your life forever, what would that be?

If you could hold on to just one memory from your life forever, what would that be?

![]() If this was to be our very last conversation, what words of wisdom would you want to pass on to me?

If this was to be our very last conversation, what words of wisdom would you want to pass on to me?

![]() What are you proudest of in your life?

What are you proudest of in your life?

![]() When in life have you felt most alone?

When in life have you felt most alone?

![]() What are your hopes and dreams for what the future holds for me? For my children?

What are your hopes and dreams for what the future holds for me? For my children?

![]() How has your life been different than what you’d imagined?

How has your life been different than what you’d imagined?

![]() How would you like to be remembered?

How would you like to be remembered?

![]() What does your future hold?1

What does your future hold?1

PARENTING AND QUESTIONS

Haven Caylor is a Doctor of Education and the father of 4-year-old twins, Ammon and Carter. In reading some of the material he’s put together for a parenting book on traveling with young children (Travel to Learning and Laughing), I was struck by the way Haven uses good questioning techniques with his children. The use of interrogatives is consistent, so the children are naturally learning to answer with names, concepts, and sentences rather than just yes or no. Haven also doesn’t use leading questions, so Carter and Ammon are accustomed to having their opinions invited rather than shaped. They contributed this conversation on an upcoming vacation for this book:

HAVEN: Carter, where are we going on our next vacation?

CARTER: Disney World.

HAVEN: Ammon, when are we going?

HAVEN: Raise your hand on this one: How are we traveling there?

CARTER: In the car.

HAVEN: Ammon, who is your favorite Disney character?

AMMON: Minnie Mouse.

HAVEN: Carter, who is your favorite Disney character?

CARTER: Donald and Goofy.

HAVEN: Ammon, why is Minnie Mouse your favorite character?

AMMON: Because she plants flowers at Mickey’s Clubhouse.

HAVEN: Carter, why are Goofy and Donald Duck your favorite characters?

CARTER: Because they’re silly!

HAVEN: When we are in Disney World at the resort, what are we going to be doing once a day with some of the characters?

BOTH: Eat with them!

HAVEN: We are! We have some sit-down character dinners. When we’re at the Hollywood studios, Ammon, which of the characters we’ve discussed—Jake, June, or Agent Oso—would you like to eat with?

AMMON: June. I like the way she sings and dances.

HAVEN: Carter, which character would you like to eat with?

CARTER: Jake, because he can do what Captain Hook can’t do and he does helpful things.

For those readers who are non-parents or non-kids, June is a character from Disney’s Little Einsteins, Jake is a Neverland pirate, and Special Agent Oso is a teddy bear who is the lead character is an animated series of the same name.

As a professional educator, Haven has taken a conscious approach to using good questioning to guide his children’s discovery about people, places, things, and events in time. In his parenting book, he has a chapter on “choosing souvenirs for future learning,” and tells a story of how having reindeer souvenirs of a previous trip sparked a series of questions about the difference between reindeer and a white-tailed deer the kids saw. After asking questions such as “Where do they live?” and “What do they eat?” Haven says,

My 4-year-old preschool children had compared and contrasted two species of deer (natural science/zoology). In Bloom’s Taxonomy of objectives in learning, Carter and Ammon were working on the 4th tier of his 6-tier pyramid. Going from the base of the pyramid (remembering), where the objectives in learning are easier, to the pinnacle (creating) of the pyramid, where you create with all the things you’ve learned, the levels are Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating. They were also learning world geography as we found the countries where reindeer lived. How was I engaging my children in this kind of learning? By relying on some souvenirs we had collected during our travels to guide the questioning.2

In a real sense, all Haven is doing is advancing the children’s natural tendency to ask simple, direct questions. In contrast to this, many adults, including teachers, have a tendency to lead children astray with bad questioning styles. Consider this common exchange:

CHILD: I’m bored.

DAD: Don’t you have some books to read?

CHILD: Yes. But I don’t feel like reading.

DAD: Would you like to ride your bike?

CHILD: No.

DAD: When I was your age I never got bored, and I didn’t have as much as you have. Why don’t you clean your room?

CHILD: Then I’d be more bored.

Now let’s see the father switch to slightly better questions:

DAD: Really?

CHILD: Yeah, there’s nothing to do around here.

DAD: So, what’s it feel like to be bored?

CHILD: You know, nothing feels like fun to do.

DAD: How else does it feel to be bored?

CHILD: You know, nothing is happening.

DAD: What do you think we can do to make today not so boring?

DAD: Where would you like to go?

Toddlers particularly can be masters of persistent questioning, but it’s probably not because they intend to annoy you. According to Leon Hoffman, MD, co-director of the Pacella Parent Child Center at the New York Psychoanalytic Society & Institute, they may ask the same question over and over again for at least three reasons. They are trying to:

1. Understand words. Children between the ages of 1 and 2 are just learning to talk, so they repeat questions to get clear on what each word means.

2. Build memory. Sometimes it takes a little while for new information to sink in to a toddler’s developing mind. Hearing a trusted parent give the same answers time and again can help drive unfamiliar concepts home.

3. Check in. Because toddlers find comfort in repetition, rewinding and replaying questions is just a way of asking for emotional support.3

Two of the three reasons, therefore, are actually a type of discovery. Don’t discourage your toddler from persistent questioning—she may be on her way to becoming a doctor.

SOCIAL QUESTIONING

Susan RoAne, aka The Mingling Maven, offers keen advice on the nature and use of questions in a social situation. In her book What Do I Say Next?, she devotes several sections to what conversation is not. “Conversation is not a soliloquy” is one piece of advice, which she precedes by telling a pointed story of a colleague who told her quite confidently that, even though RoAne had written the (best-selling) book How to Work a Room, that he really knew how to work a room. In fact, he was so good at it that when he left a room, people who remained in it felt a void. RoAne correctly assessed that they welcomed the void. She and her friend Jeanie had encountered him at an event where he had immediately launched into a 10-minute update on his life and recent achievements. And then he walked away:

Gary never asked a question of either of us, and made no attempt at anything that resembled a conversation. Jeanie had a client in his field, which she happened to mention at one point. If he had shut his mouth and listened, he would not have blown this lead from her. I had mentioned that I was writing this book, giving him a topic to bounce off of, but he lacked the interest to inquire about it.4

The incident triggered a recollection that RoAne had of a colleague’s “Five-Minute Rule”: If a person you’re speaking with does not ask a question in the first five minutes, it’s time to leave.

DATING AND QUESTIONING

Building on RoAne’s “Five-Minute Rule,” if you are on a date and the other person asks no questions about you, you could walk away—or you could dismiss the faux pas as the nervousness associated with a date trying to impress you or amuse you. So, I’d say give him/her 10 minutes to start asking you about yourself. There is the opposite problem of course—which RoAne calls a “probe-lem”—and that is the situation in which the date acts like an interrogator. A barrage of “Where did you go to school?” “What’s your sign?” and “Who did you vote for?” is the stuff of a bad date, no matter how attractive the person it.

The nature of your questions on a date speaks volumes about what you’re genuinely looking for a in a companion, as well as what you have to offer. Keeping the conversation focused on skiing or going to parties suggests you want a playmate. Questions about the future suggest you want a wedding. ASAP.

Here’s a story that illustrates the importance of asking the right questions. Paul and Ann met on her first day at the office; her cubicle was next to his. They had an immediate attraction and he asked her out before the day was over. Ann is the kind of person who enjoys learning about what makes a person tick. Her questions on their first date kept them talking almost all night about everything from favorite novels to space travel.

Three months later, their relationship still held magic for both of them and they started talking about moving in together. And then, one of his former girlfriends showed up at work and took him to lunch. They came back two hours later, with the girlfriend showing signs of having had too much Chianti with her pasta. Leaning into Ann’s cube, she said in a snarky tone, “His mother won’t like you either,” and then she swayed toward the exit.

Later that night, when Ann and Paul were together, she asked why the girlfriend had said that. Paul explained that he’d never had a girlfriend his mother did not think was a gold-digger. In all those three months, Ann had never asked Paul about his background because she figured he would talk about it if he wanted to. Instead she got to know him inside, never finding out that his mother came from an enormously wealthy family.

“Don’t worry, Ann,” he said to her. “There are lots of reasons why she won’t come to that conclusion about you.” The story had a happy ending.

PERSONAL QUESTIONS AND PERSONALITY

Anyone can be trained to ask good questions, and even people who are reticent to ask questions can generally do it comfortably in a professional setting. In a social or personal situation, it can be a very different matter, however.

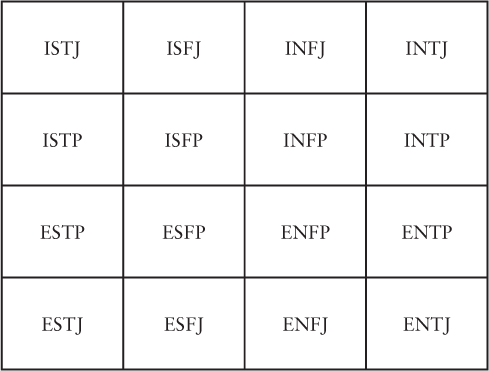

You may be predisposed to ask questions about feeling and values—“What can we do about puppy mills?” Or, you may be inclined to ask questions that essentially render an opinion or some sense of how you think the question should be answered—“Why do you think Congress has been foot-dragging on immigration reform?” I think the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is a useful tool to provide insights on how a person might be predisposed to approaching questioning. Understanding your predominant type and that of people you interact with often could improve your questioning and listening. Ann’s approach to questions with Paul captures exactly who she is in terms of the MBTI: Introvert, Intuitive, Feeling, Perceiving. Princess Diana is considered a famous example of an INFP. On the Myers-Briggs Website (www.myersbriggs.org), INFPs are described as:

Idealistic, loyal to their values and to people who are important to them. Want an external life that is congruent with their values. Curious, quick to see possibilities, can be catalysts for implementing ideas. Seek to understand people and to help them fulfill their potential. Adaptable, flexible, and accepting unless a value is threatened.5

In considering the characteristics of the various types summarized by the following grid, I concluded that the “judgers” were probably least likely to ask open-ended questions. The Js are those “who prefer to get things decided,” as opposed to the perceivers, who “prefer to stay open to new information and options.” Most of us tend to wiggle from one block to another, depending on context, so there is no absolute associated with this view of who makes a good questioner.

In considering which types might be better than others in blatant lies, inconsistencies, and evasions, I would turn again to How to Spot a Liar, which analyzes the possibilities according to temperament types. Based on Myers-Briggs profiles, the temperament types are: rationals, idealists, artisans, and guardians. They were first categorized as such by David Kiersey and Marilyn Bates in their book Please Understand Me. In brief, rationals are primarily characterized by a combination of intuiting and thinking. Senior military leaders and CEOs would likely fall into this category. With people like that in mind, you might assume they are good liars; in fact, they don’t lie well because they are not accustomed to thinking that they need to lie. Idealists, who combine intuition and feeling, tend to make good liars. They just want everybody to get along, and sometimes, evading the truth is the best way to help make that happen. (“No, you don’t look fat in those pants!”) Guardians are sensing-judging people who don’t tend to lie well. They would try to avoid situations that might involve omitting or sidestepping the truth. The sensing-perceiving artisans “get you in the ballpark of the truth,”6 according to Deborah Singer Dobson, the expert cited in this section of How to Spot a Liar.

QUESTIONING TO KNOW YOURSELF BETTER

You’re a character in the reality show you call your life. Just as questions have helped me understand the characters I’ve created in role-playing situations in training interrogators, I believe they can help you as well. Asking yourself good questions about yourself can lead to some wonderful revelations about your motivations, priorities, goals, and so on.

In training intelligence collectors, I had to develop an adversarial persona who was able to answer all of the questions I knew they would ask when I was testing their abilities to gain cooperation and seek information. My process was to envision a person in a particular environment, give him a personal and professional element, and then overlay it with regional culture and language. Some of the roles were very technical and scientific, and all were woven around the personal motivations and vulnerabilities that we all have.

I have been so many different people in the last 25 years that I fear in my old age my brain may call on one of the less friendly characters I’ve been and lock its memory there. No one in the nursing home will want to sit with me during meals. They’ll just say, “Jim Pyle? Oh, that’s the mean guy over there. You won’t want to talk to him!”

My students have had to question me as a foreign soldier, a sailor, an airman, a drug courier, a suicide bomber, a terrorist cell leader, and an ex-patriot with information on a foreign government’s nuclear, political, or military plans. Some roles were simple and easy to exploit whereas others contained layers and nuances not easily detected or exploited. For many students, finding out what I knew about research into the effects of high-frequency pulse radiation and its effects on the hippocampus of the brain was a little more involved than why, as a disenfranchised young man from a poor village, I was willing to carry drugs across the border so my family could eat.

Discovery questioning proved quite helpful as I developed roles for the students to question. It’s straightforward: If the information students are going to acquire is the result of asking questions, then the process of building a role begins with questions. It follows exactly as discovery questioning should: a basic question with the necessary follow-up in all the areas of people, places, things, and events in time.

In the case of my identity as Eduardo Morales, I was a lone individual who emerged from the bulrushes along the beach near Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, with nothing more than a diver’s knife and 500 pesos, wearing a modern U.S. military life jacket. I became Eduardo by asking myself questions: Who am I? Who makes up my family? Who are my friends? Where did I come from? What was my job? What schooling did I have? How did I get to this place? Why did I come to this place? Eduardo was built by questions and he was revealed by questions. In other words, he came apart the same way he was constructed.

If I were going to play you in such an exercise, what questions would I need to answer so that I could get away with it?

EXERCISE

Keep a journal for two weeks related to questions in your personal life. If you are keeping the Monday-through-Friday journal as suggested in the previous chapter, then you could just focus this journal on evenings and weekends.

Begin by making notes in three areas of your past questioning:

1. List five questions you asked that made a difference in your personal life. Put a short notation as to why you feel each served you well.

2. Add five questions you wish you had never posed. When it comes to your personal life, you may have some anxiety over these questions, so don’t bother to make a notation on why you have a tinge of regret about asking them. No need to rub salt in the wound.

3. Add five questions you believe you should have asked differently.

![]() How do you wish you would have stated the question?

How do you wish you would have stated the question?

![]() How would restating the question have potentially changed the answer you got?

How would restating the question have potentially changed the answer you got?

In your journal, keep notes about how the structure, placement, frequency, and other pertinent factors related to your questions has changed.

1. Record one question each day that made a difference in terms of a personal relationship. (Note: You might have asked a question that threw someone into a state of rage. That counts as making a difference.)

2. Record one question you wish you hadn’t posed. (If none, then congratulations.)

3. Record one question you think would have gotten a better answer if asked a different way. (If none, then you’re probably kidding yourself.)

![]() How do you wish you would have stated the question?

How do you wish you would have stated the question?

![]() How would restating the question have potentially changed the answer you got?

How would restating the question have potentially changed the answer you got?