Chapter 2. Drawing Expressive Lines

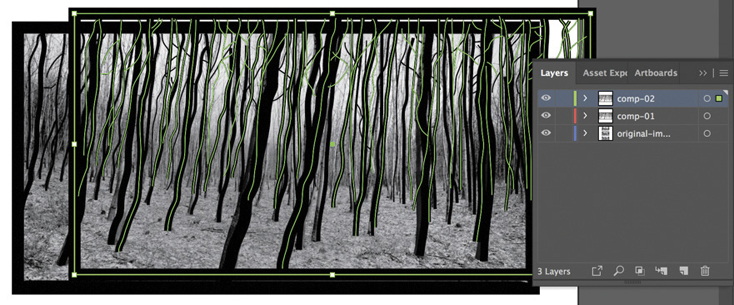

The Exercises in this chapter encourage you to study lines as design elements. Specifically, you’ll examine the lines found in a landscape photograph of trees. As you can see in FIGURE 2.1, the dark lines produced by the bark of the trees are read in stark contrast against a winter sky. You’ll use the Pencil and Paintbrush tools and explore the Gradient and Layers panels in Adobe Illustrator.

A group of similar lines creates a repeated pattern that is easy to read and understand when the weight (or thickness) of the lines is contrasting. Thicker lines will seem to push to the front of the composition, while thinner lines recede into the background. The same is true for dark and light values, respectively. In Chapter 1, The Dot, the Path, and the Pixel, we focused on the separation between the foreground and background of the composition space. In this chapter, lines will express the individuality of each tree in the landscape. Although foreground and background are less likely to shift in this composition, you’ll begin to see how the sizes and values of design elements affect human perception.

Because a line connects two dots, it makes sense to follow a chapter study on dots with one on lines. In her book Decoding Design, Maggie Macnab articulates the complexity of the line by referring to the anchor points at each end of the line as a pole. “The poles, while repulsed in their division, are attracted back to one another—the paradox of this principle” [1]. A line can be used to join two elements or to separate parts of a whole (FIGURE 2.2).

A line can be tight or loose, meaning it can be straight and mechanical (tight) or flowing and organic (loose). The plans for an architectural space, for example, will be clean and organized. The “hands” of Alicia Eggert and Mike Fleming’s Eternity clock form a composition of tight, black lines on a contrasting white background (FIGURE 2.3), while flowing water in Colleen Ludwig’s Cutaneous Habitats: Shiver demonstrates free-form movement (FIGURE 2.4).

The exercises in this chapter will show you how to create a series of lines using the Pencil and Paintbrush tools in Adobe Illustrator. You’ll experiment with various strokes (line weights) and values to alter the perception of depth between the foreground and background elements.

Saving and Sharing Files

When you save a file, you have many choices to make. How will you name the file? Are you collaborating with others? If so, will you all adhere to the same naming conventions? What type of file do you want to save? What do you plan to do with the file once it’s saved? If you are submitting files to a call for projects or an instructor, have you been given directions about the file name and its format? How you answer these questions will play a role in how you choose to name and save your files. What follows are a few general guidelines that will help you determine how to save and share your files.

File Naming

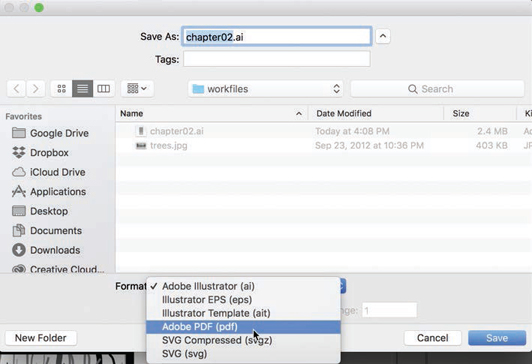

If an image is saved in two different formats, the files will have different file extensions. Therefore, you can keep the same file name in place, resulting in something like: x-burrough.ai and x-burrough.pdf so it’s clear the two files refer to the same project.

File names should be concise, organized, and descriptive. If you’re working on a series of files or collaborating with others (for instance, if you’re a student submitting a file to an instructor who is in effect “collaborating” with you and all of your peers), you should consider naming all files for one project with a consistent naming convention. File names should not include spaces or foreign characters, and they should always include an extension (for example, .ai, .psd, .jpg, and so on). The file name “My BEST picture ever!!!!!!!” is sloppy—it includes spaces and exclamation points, mixes upper- and lowercase letters, lacks the file extension, and, worst of all, it doesn’t describe the content of the image. In my classroom, I ask students to label all files with a description followed by their first initial dash last name dot file extension, all in lowercase, for example, chapter02-x-burrough.ai. I insist on file names with all lowercase letters, because many of my foundations-level students later enroll in interactive media design classes where lowercase letters are the norm. (It saves time troubleshooting code if you know that the file names don’t utilize uppercase letters.)

In addition to how you name your files, you have to consider the saved format. Best practices include always saving the file in its master or native format (for instance, always save an Illustrator file in .ai format). The master file can be edited at any time in the application in which the file was originally developed. In addition, you may want to save a separate file for sharing. The file formats JPG and PDF are often used for sharing photographic images or type and image layouts. These formats compress the file (which means that some data is lost), resulting in a smaller file size. Most importantly, viewers don’t need Adobe applications in order to open or print these formats, as all computers can display JPG and PDF files via basic previewing applications, the freely downloadable Adobe Reader application, or even a web browser. Although applications that can open a PDF can read recent versions of Adobe Illustrator files, commercial printers will likely request the file in PDF format. It’s common to save two versions of the same file: one in the master format (which can be especially useful for later revision) and one in a format conducive to sharing a finished work.

Place and Lock an Image

Place and Lock an Image

Copy the original photograph by Aleš Jungmann, trees.jpg, from the folder chapter02-workfiles and paste it into a folder named chapter02.

Workspace > Essentials Classic

Set the workspace to Essentials Classic by choosing it from the menu in the Application bar or by choosing the Window menu > Workspace > Essentials Classic.

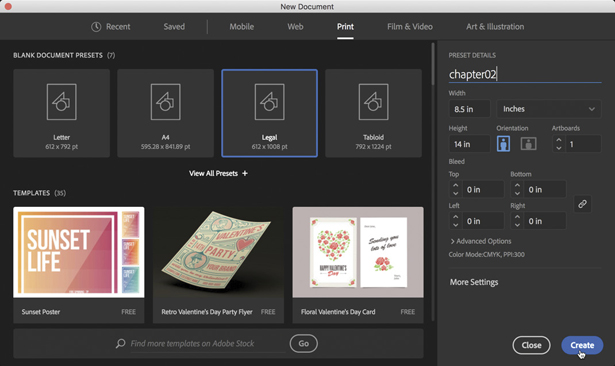

Open Adobe Illustrator. Choose File > New and adjust the following settings: Select the Print tab and set the paper size to Legal (612 by 1008 points or 8.5 by 14 inches). In the Preset Details (on the right side), name the new file chapter02 and choose Inches from the Units menu (FIGURE 2.6). Click Create.

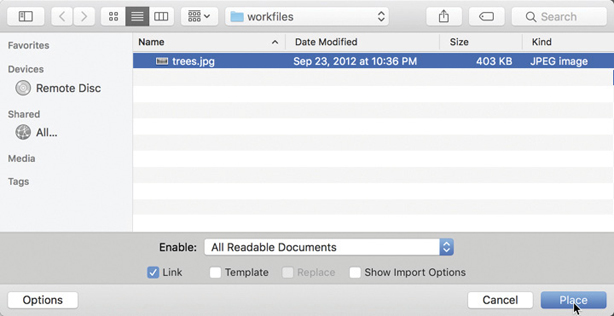

Figure 2.6 Start your new document by selecting and modifying a profile. Choose File > Place to add the photograph of trees to the artboard. In the dialog box that opens, browse to the file trees.jpg in the chapter02 folder you created in Step 1 (FIGURE 2.7). Your cursor icon will change to a loaded graphics cursor—click anywhere on the artboard to place the image (FIGURE 2.8).

Figure 2.7 Browse for a file to add it to the artboard using File > Place.

Figure 2.8 Click the loaded cursor to place the image onto the artboard. Workspace

You can set or reset the workspace anytime. Reset the workspace by choosing Window > Workspace > Reset [whichever workspace is active]. You’ll want your workspace to look like mine so the screenshots are more likely to reflect what’s in front of you.

The photograph will appear small on the page. Because you’ll eventually create your own vector abstraction based on the image, don’t worry about file resolution for printing purposes. (This topic is thoroughly investigated in Chapter 5, Resolution and Value.) In this situation, it’s safe to enlarge the photographic image. Use the Selection tool to click the image, and then hold the Shift key while dragging any of the four corners outward from the image. Drag the image to the top of the artboard while keeping an eye on the margin spacing—aim for equal margins on the top, left, and right sides of the image (FIGURE 2.9).

Figure 2.9 When the image is in position on the artboard, you’ll see equal margin spacing on the top, left, and right sides. There should be plenty of room for you to work toward the bottom of the page. You’ll be drawing lines on top of the image in the next exercise. If you don’t lock the image, you may unintentionally select and move it while you’re trying to work. With that in mind, lock the image now in anticipation of the next steps. This is easily accomplished with the Layers panel. Click the Layers icon in the panel dock on the right side of the application window (FIGURE 2.10). The Layers panel will appear. Any paths you draw or images you place on the artboard appear in the Layers panel.

Figure 2.10 Click the Layers icon to access the Layers panel. (You can also choose Menu > Layers.) The Layers panel displays paths and images added to the artboard. Click the sideways arrow next to Layer 1 to flip it into a downward pointing arrow, revealing content saved on this layer (FIGURE 2.11). The image appears in Layer 1 as <Image>. Click the unlabeled box to the left of <Image> to lock it inside Layer 1 (FIGURE 2.12).

Figure 2.11 By default, all media is stored in Layer 1. You can expand and collapse a layer by clicking on the arrow to the left of its icon.

Figure 2.12 Click the unlabeled box to the left of a layer to lock it inside Layer 1. Finding Panels

If the Layers panel icon is not easily visible, you can always open it by choosing Window > Layers.

Understand Layers

Understand Layers

The Layers panel is a standard feature in many Adobe applications. Illustrator and Photoshop treat layers slightly differently because of the difference between how art is created in vector and bitmap applications.

In Illustrator, you begin with one layer. Each time you add content to the artboard, it’s added as an element that’s part of Layer 1. You can lock individual elements. You can lock entire layers. You can create and delete layers. You can rearrange what’s referred to as the stacking order of layers to make content appear more in the foreground (towards the top of the panel), or background (towards the bottom of the panel) of the document, in front of or behind other elements. When you click where there are multiple elements, the topmost unlocked element will be selected. Much of this is also true in Photoshop, although you’ll see in later chapters that it’s safer to work with each element (graphic or text) on its own layer in bitmap applications.

One of the primary roles of layers is to help you organize your document. In the following exercises, you’ll create new layers to make the content of separate compositions easy to find.

Create Lines with the Pencil Tool

Create Lines with the Pencil Tool

Click the Create New Layer button at the bottom of the Layers panel (FIGURE 2.13). Layer 2 will appear on top of Layer 1.

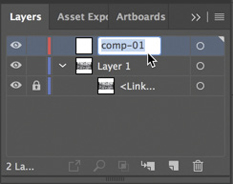

Figure 2.13 The Create New Layer icon appears at the bottom of the panel next to the Trash icon. (I always tell students that birth and death live next to each other.) The bottom of a panel is often the location for Create New and Trash icons in Adobe programs. Double-click the name Layer 2 and type the new name comp-01; then press the Return/Enter key or click anywhere outside the text field to set the text (FIGURE 2.14). You’ll draw all the new lines for the first composition on this layer.

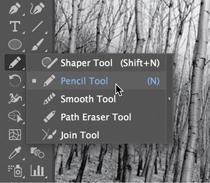

Figure 2.14 Double-click the name Layer 2, and simply type on top of its name to rename it. Find the Shaper tool in the Tools panel on the left side of the application window. Notice that the Shaper tool, like many of the tools, has a small arrow in the bottom-right corner. Pressing and holding the mouse button on the arrow reveals several related tools that are bundled with the visible tool. Press and hold on the Shaper tool and select the Pencil tool (FIGURE 2.15).

Figure 2.15 Clicking the small arrow in the lower-right corner of a tool’s icon reveals related tools that are bundled with the top tool. The default fill and stroke values for the Pencil are no fill and a black stroke. Check the Fill and Stroke controls at the bottom of the Tools panel or on the Control panel and set them to no fill with a black stroke if the default settings have been modified (FIGURE 2.16).

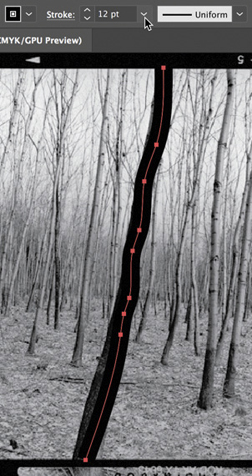

Figure 2.16 Set the Pencil tool to a black stroke with no fill: Click the Stroke button at the bottom of the Tools panel (or the left end of the Control panel) and select the black swatch; then click the Fill button and select the [None] swatch. Use the Pencil tool to draw a line along the contour of the tree that’s most in the foreground (or the tree’s outline—you can choose the side). When you finish drawing the line, it will remain selected. Modify the weight of the line by increasing its stroke value in the Control panel at the top of the application window (FIGURE 2.17). I set mine to 12 points, resulting in a line that’s nearly the same width as the trunk of the tree.

Figure 2.17 Modify the weight of a selected line by changing its stroke value in the Control panel. Repeat Step 5 to trace enough trees to create a recognizable abstract line drawing of the photograph. Change the weight of each line (the stroke value) as you develop lines that appear in the background (FIGURE 2.18). Watch out for areas where two lines seem to connect (for instance, in those tiny sideways branches in the background). When you draw a line with the Pencil tool, it’s constructed by a series of anchor points. The line remains selected after it’s drawn. If you draw another line on a new area of the artboard, the first line becomes deselected, and the second line is selected. If you try to draw a line that connects with the first line, instead of creating a new line, you’ll end up modifying the first (selected) line. Inevitably, you’ll do this when you don’t intend to. You’ll have to manually deselect the first line—use the Selection tool to click in any white space on the artboard—then reselect the Pencil tool and draw the second line.

Figure 2.18 Continue to trace trees. Watch out for intersecting lines. You will need to deselect the path before drawing a new line that intersects with the previous drawn line. Keyboard Shortcut

While you’re using the Pencil tool, you can easily access the Selection tool by pressing the Command key in macOS (or the Ctrl key in Windows). Holding this key while you’re using the Pencil tool temporarily converts the tool into the Selection tool. When you release the key, the Pencil tool returns.

Select the Rectangle tool, and draw a black border around the image, covering the film edges. Modify the stroke value to match the weight of the line shown at the edge of this photograph (FIGURE 2.19).

Figure 2.19 Use the Rectangle tool to create a border.

Duplicate the Composition

Duplicate the Composition

Rename Layer 1 so that it better describes the content on the layer. I named mine original-image.

Toggle off the eyeball (or visibility) icon next to the comp-01 layer so you can see the original image layer set behind it (FIGURE 2.20). The stacking order of the layers prevents you from seeing lower-level layers when top layers contain content that covers the same areas.

Figure 2.20 Toggle off the eyeball icon in the Layers panel to view the original layer. Expand the original-image layer if it is not already expanded and unlock the image (FIGURE 2.21).

Figure 2.21 Expand the original-image layer and click the lock icon to unlock the image. Select the image within the Layers panel by clicking in the last column to its right (FIGURE 2.22), called the selection column. When you see a box (mine is blue, yours may be another color), you’ve selected a layer element. Look on your artboard to see that the image has been selected.

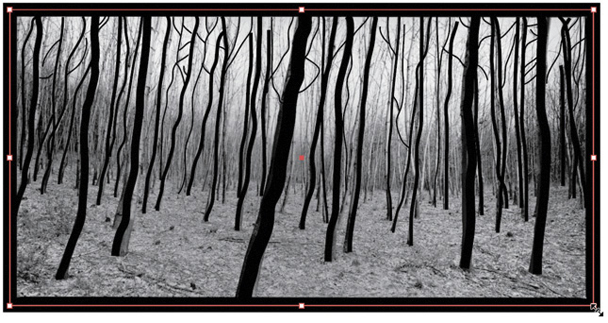

Figure 2.22 Select the image within the Layers panel by clicking the blank area at the far right of the layer. Choose the Selection tool. Option-Shift-drag/Shift-Alt-drag to create a copy of the image beneath the first original image. Repeat this process to make a second copy (FIGURE 2.23). Once they are placed, edit the spacing of the margins (the negative space) so they are even. You’ll reference these images when you create the next two compositions.

Figure 2.23 Choose the Selection tool and use Option-Shift-drag/Shift-Alt-drag to copy the image twice. New images appear in the original-image layer in the Layers panel.

Add a Gradient Background

Add a Gradient Background

Click the eyeball icon to toggle visibility for the comp-01 layer on. Don’t expand the layer. Click in the selection column (FIGURE 2.24). This selects everything contained within the comp-01 layer. Every pencil stroke you created is selected. Choose Edit > Copy, or press Command-C/Ctrl-C.

Figure 2.24 Clicking in the selection column of the collapsed layer selects everything stored within it. Before pasting all those paths, create a new layer and title it comp-02.

Keyboard Shortcut

Press the Shift key and the appropriate arrow key to move items faster—they travel by ten units rather than one unit at a time.

While the comp-02 layer is active, press Command-V/Ctrl-V or choose Edit > Paste. If your document is like mine, you’ll end up with a pasted set of lines that are not aligned with the second original photograph (FIGURE 2.25). While the lines are selected, use the arrow keys to move the composition of lines into position over the second photograph. I used Shift-Left Arrow to move my composition of lines to the left significantly faster than if I didn’t use the Shift key.

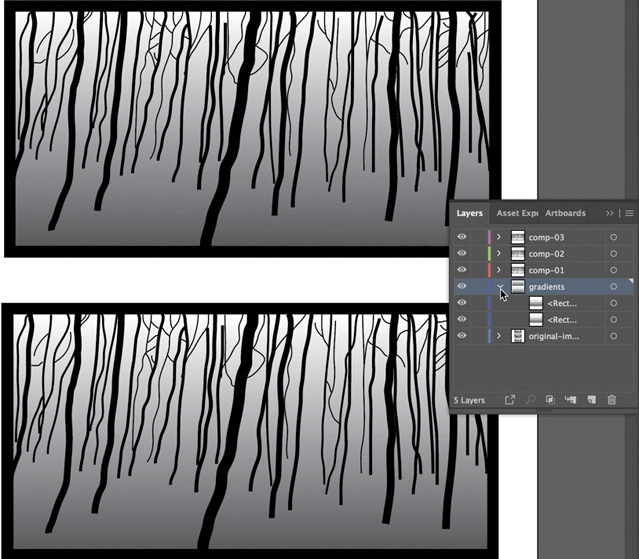

Figure 2.25 Pasted items land on a new layer. Create a new layer to store gradient fills. Name the layer gradients and drag it to the stacking position just above the original-image layer (FIGURE 2.26).

Figure 2.26 A layer can be moved to a new stacking order by dragging it into position in the Layers panel. The gradients layer is dragged into stacking position just above the original-image layer. Deselect the lines on the comp-02 layer if they are selected. Click the gradients layer in the Layers panel to make it active. Draw a rectangle (use the Rectangle tool) on the gradients layer that’s the same size as the compositional space of the middle photograph. Make sure the Fill icon is selected either at the bottom of the Tools panel or on the Control panel, and double-click the Gradient tool to open the Gradient panel on the right side of the document window. Click the tiny triangle to the right of the gradient swatch to open the gradient menu, and choose the first option to apply a two-point linear gradient from white to black (FIGURE 2.27).

Figure 2.27 Use the Gradient tool to fill a rectangle in the gradients layer. Modify the angle of the gradient to −90 degrees. If you choose positive 90 degrees, the darker value will be on top, where the sky should appear white (FIGURE 2.28).

Figure 2.28 Choose Window > Gradient to modify the gradient settings. The Type setting determines how the gradient is distributed and the angle determines the direction of the gradient. Be Careful!

If you followed the last few steps but didn’t see a change on your artboard, you may have deselected the gradient fill before modifying the settings in the Gradient panel. Select the gradient fill on your artboard and then try those steps again.

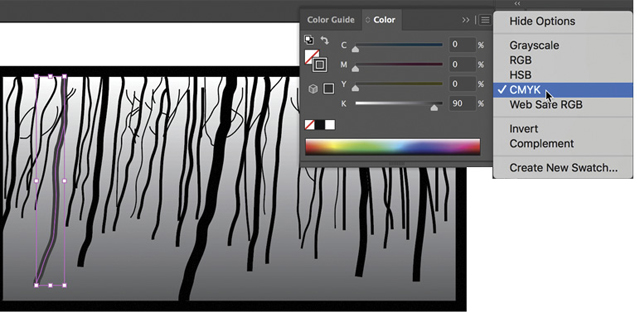

You can modify the colors at the two ends of the gradient spectrum at any time. You can also add an additional “pit stop” of color or value by Option/Alt-dragging one of the color chip handles in the Gradient panel. Double-click the black color chip near the bottom of the Gradient panel. This will open a Color panel specific to the Gradient settings. Adjust the dark value so it’s 80% black (dark gray) rather than true black: Change the 100% K (or black) value to 80% (FIGURE 2.29).

Figure 2.29 Double-click the black chip in the Gradient panel to open a Color panel controlling the Gradient settings. Set the dark point to 80% black. Print Profile

Because you used the Print profile when setting up your document, the Color panel will display with CMYK or cyan, magenta, yellow, and black values.

Be Careful!

Value and Tonal Range 80% black is a value in the tonal range from white to black. Value and the tonal range of an image are explored in Chapter 5, Resolution and Value.

Create Depth with Contrasting Values

Create Depth with Contrasting Values

In this third composition, you’ll modify the value of some of the lines to create greater compositional depth. Depth and space are alluded to in two-dimensional space by properties that appear in our three-dimensional reality. The size of the trees becomes smaller as the viewer perceives the depth of the forest (both in terms of their height and the line weight of their contours). The overlapping position of the trees also helps the viewer perceive depth. These two values (size and overlap) were translated from the original photograph in black and white. However, atmospheric perspective accounts for the depth that’s perceived due to less visibility through contrast as items are farther from the viewer’s plane of vision. In this case, you’ll need to modify the values of the trees toward the background to allude to the atmospheric perspective.

You’ll also add a final diffused line to the third composition to separate the horizon line from the ground. All aspects of the original image can be translated with one basic design element: the line.

Repeat Steps 1, 2, and 3 from Exercise 4 to create a third composition. This time copy comp-02 and name the new layer comp-03. You’ll also need to copy, paste, and position the gradient for the third composition on the gradients layer (FIGURE 2.30).

Figure 2.30 A view of the Layers panel with the new layer, comp-03. Leave the tree you drew in the very front black (the one with the trunk that extends all the way to the bottom of the frame). Choose the Selection tool and click one of the trees/lines near the foreground. In the Color panel, open the panel menu (in the upper-right corner) and choose Show Options. Set the Stroke value to 90% black (FIGURE 2.32).

Figure 2.32 Use the Selection tool to select a line; then change its Stroke value using the Color panel. Select the next set of near-foreground trees together. You can select multiple lines by pressing the Shift key as you click each one. If you accidentally add a line to your multi-selection, Shift-click it again to remove it. Set the value to 80% black (FIGURE 2.33).

Figure 2.33 Hold the Shift key and click to select multiple trees with the Selection tool. Use the Color panel to decrease the stroke values on all of the selected lines. Repeat Step 3 as you set another group of lines to 70% black, then 60%, and so forth as you move backward in the compositional space. You may leave some of the smaller twigs black as they overlap other tree branches. This contrast between black and mid-gray will help the viewer see the details in the forest.

Use Master Files and Shared Files

Use Master Files and Shared Files

When the design is finished, save the master file—either press Command-S/ Ctrl-S or choose File > Save As to rename the file or to save a duplicate of the file in a different location on your hard drive. Save the file in master format, meaning .ai (Adobe Illustrator), the format that is specific to the Illustrator application. You can click OK through the Illustrator Options dialog box unless you’ll need to open and edit the file in a prior version of Illustrator. (If so, see the following sidebar about backward compatibility.)

Use of the .ai format is imperative: If the file is in this format, you’ll always be able to open and edit the file using Illustrator. However, you’ll also want to save your work in a format optimized for sharing. For this purpose, vector graphics are most often saved in PDF, SVG, or PNG file formats. Save the file as a PDF now. Choose File > Save As (Shift-Command-S/Shift-Ctrl-S) and then choose Adobe PDF from the Format menu (or in Windows, from the Save As Type menu) (FIGURE 2.35). The next dialog box contains a lot of information about how the PDF will save, which is more thoroughly covered in Chapter 11, The Grid. For now, click the Save PDF button and view the two files in your folder. As described earlier in this chapter, you can use the same name on both files because the file extensions (which are, officially, part of the name) are different.

Figure 2.35 File formats, such as PDF, are available in the Format menu (or in Windows, in the Save As Type menu) of the Save As dialog box.

Lab Challenge

Lab Challenge

Find or take a photograph of an athlete, and develop a “tight” pencil illustration of their action or movement using the Pencil tool (or by exploring the Paintbrush tool) in Illustrator.

Reference

[1] Maggie Macnab, Decoding Design (Blue Ash, OH: HOW Books, 2008), 62.