Introduction

In many ways, state provision of mainstream schools is standardised. Funding for new school buildings is based on fixed formulae and briefing has long tended toward a ‘kit of parts’ approach, as described in Building Bulletin 103 and its predecessors, Building Bulletin 98 and 99.i

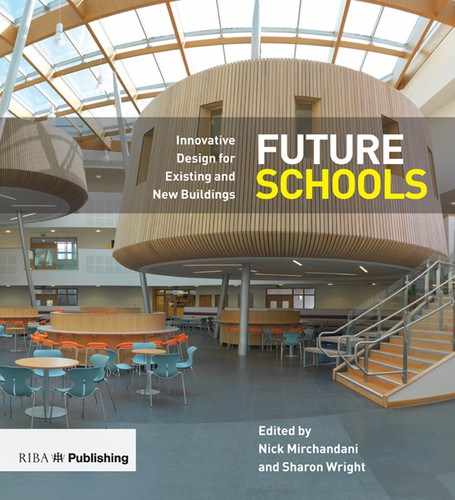

Michael Faraday Community School, Southwark (Archial NORR). Providing nursery, primary school, adult education and community facilities, the circular main building accommodates class bases arranged as a ring around the ‘Living Room’ – a large open-plan learning environment at the heart of the school. A smaller stand-alone pavilion, ‘The Ballroom’, contains the school’s dining and main hall facilities.

Since the James Review of Education Capital 2011, government has also advocated standardisation in the design and construction of schools, with the explicit aim of delivering both cost and time efficiencies. For the Priority School Buildings Programme (PSBP) and its contractors framework, the Education Funding Agency (EFA)ii has produced standard Facilities Output Specifications as well as Baseline Designs for primary and secondary schools of various sizesiii. These designs are not intended to be proscriptive however, but seek to illustrate how the area and performance criteria can be achieved affordably.

In comparison, variety in special educational needs (SEN) schools tends to be more pronounced. Although some may be relatively generic in their provision, others are tailored so precisely to the needs of their students that they must adapt for each new intake. Variety in SEN design is therefore beyond the scope of this chapter.iv

Likewise, independent schools are not constrained by particular formulae and standards, other than very limited legislative requirements.v Building Bulletins and other guidance, while intended primarily for state schools, are nonetheless of relevance and value.vi

Even in the state mainstream however, no two schools are quite the same. While certain differences are self-evident, such as the number of students or the age range served, others exist even where schools have similar populations. Such variety falls into different but overlapping categories – educational, social and physical. Most importantly it exists in the more nebulous concept of ethos – a particular school’s individual style and its belief system regarding its function and place within its community.

Educational variety

Although the introduction of the national curriculum in the late 1980s sought to standardise what is taught in schools, each has its own distinct approach to pedagogy, based both in the long-term – through its history, governance and reputation – and in the shorter term, through the particular expertise and concerns of its staff and governors. In recent years, such variety has been embraced politically, for offering choice to parents and in recognition that traditional academic, vocational or comprehensive models may not meet the needs of all pupils, or provide the skills required in newer industries.

Like the national curriculum, specialist status was introduced following the Education Reform Act of 1988. Although additional funding was withdrawn by the coalition government of 2010, the idea of encouraging diversity in schools persists and extends beyond specialist status itself. Initiatives from both sides of the political spectrum have led to entirely different categories of school – first academies and more recently free schools, university technical colleges and studio schools. All are funded independently of local authorities and all enjoy certain freedoms when planning and delivering the curriculum.

Other recent developments in education also serve to enhance variety. For example, increased integration means that many mainstream schools now enjoy expertise in particular areas of SEN provision, including learning difficulties, social, emotional and behavioural issues or particular physical impairments. Similarly, school buildings increasingly provide for education outside core school hours or age range. Such activities include extended use by the school population itself (eg after-school homework clubs) and use by other educational providers such as adult education and lifelong learning initiatives.

Even when schools are identical in terms of curriculum delivery, the way it is delivered and the structures in place to support this can vary widely. Pedagogical styles and preferences differ from school to school, sometimes with little impact on the built form but sometimes with major implications. An extreme example would be a ‘school within a school’ model whereby a large school is subdivided into smaller units with distinct student populations and educational, pastoral and support structures to match. In briefing a new project, such requirements may be already established and their design implications understood, as often the case with the larger academies chains, or they may need to be explored and their implications tested with end users.

Stationers’ Crown Woods Academy in Greenwich (Nicholas Hare Architects) comprises nine separate pavilions in a ‘school within a school’ arrangement. Four ‘college’ buildings provide the core curriculum for 450 students each, three for students aged 11–16 and one for the sixth form. The remaining pavilions provide specialist and shared facilities.

Other things to consider:

- Does the school have specialist status or strengths in particular areas of the curriculum? Should this impact on the level of provision, the type of provision or its location within the school? For example, does a particular subject require additional or specialist facilities and should it be located in a prominent or central position? Alternatively, should the specialism be dispersed throughout the school to impact on all areas of the curriculum?

- Are there particular curriculum groupings at the school? For example, does it have a traditional subject-based departmental model or larger faculties that group together such departments? How do these relate to each other? Do the school require particular adjacencies to facilitate or encourage cross-curricular or project-based activities?

- Does the school favour a particular pedagogical style of delivery or does it require flexibility? How does this impact on the kind and size of space required? Should all spaces be enclosed or might some be open-plan? If the latter, how are acoustic issues to be addressed?

- Are all teaching spaces similar or are a variety of spaces required? Are breakout areas for smaller group work needed adjacent to more formal learning spaces so the two can be used in conjunction? Is transparency required between them to allow supervision?

- Are students to work in traditional classes of 30 or might the school require larger spaces for lectures, team teaching or lead lessons? Are such spaces required in particular curriculum areas or are they a central resource for all to use when required? Are they a permanent requirement or could they be created only when needed, for example by amalgamating two standard teaching rooms using a sliding-folding partition?

- Are particular teaching and learning spaces specialist or general, formal or informal, specific or flexible? Might they also accommodate social activities at some times during the day? How do the ICT and FFE (furniture, fittings and equipment) solutions support its use?

- Is there a preference towards a traditional model whereby individual teaching rooms are ‘owned’ by specific members of staff? This decision can have a major impact on space requirements as it tends to lead to generic teaching spaces, sized to allow delivery of the whole subject curriculum. If teachers are not associated with specific rooms then a variety of more specialist accommodation can be provided, allowing them to select the space most suitable for a particular activity.

- Does teaching and learning occur in the same spaces for the full age range of the school or are some learning areas age-specific? This is standard practice in primary schools and common for sixth forms but some secondary schools also like to distinguish key stage learning areas or provide a distinct year 7 zone. If such distinction is preferred, does it apply only to general teaching spaces or are some areas of the specialist curriculum such as science also dispersed? If so, how does this affect staffing and servicing?

- If the school has a sixth form, is their teaching delivered within curriculum zones or within a defined sixth form area? What about spaces for private study? If a sixth form base is preferred, is this integrated with social spaces?

- How are SEN, learning support and inclusion accommodated within the school? Should particular facilities be located centrally or remotely? Should they be grouped or dispersed? Is discrete access and egress required?

- How and where are staff to work when not teaching? Are separate working areas required in each curriculum area or should they be centralised? How is the senior leadership team structured? Should they be grouped together or dispersed to allow local presence around the school? Are individual offices preferred or shared spaces to encourage team working? If the latter, are separate rooms required for meetings and confidential activities?

- Where and how are exams to be accommodated, in the sports hall and/or elsewhere? What are the implications on the location of these facilities, acoustics, furniture storage and the ongoing delivery of the curriculum while they are in exam use?

- Do certain learning facilities require direct access to the outside, either functionally (eg for deliveries) or to allow external learning activities? What services and facilities might be required to support external learning?

- In primary or all-through schools, is a nursery provided? What is the relationship between the nursery and the school, are they managed together or independently? What facilities are separate and what might be shared? If the nursery is integrated with the school, is it to be part of a foundation stage with reception?

- Will particular learning facilities (eg sports or performing arts) enjoy extended or out-of-hours community use? Are there to be supplementary learning facilities (in addition to school accommodation) and, if so, will the school enjoy use of these during the day? How does this impact on their location within the school and will they require secure zoning?

Social variety

All schools exist within a specific geographical and social context. In the case of primary or urban schools the area served may be very small and homogeneous. In contrast, large and rural secondary schools may have a very wide catchment including distinct and potentially different communities. Each school is therefore a product of its particular population, with variety possible within schools as well as between schools.

Differences in students’ backgrounds can take many forms – economic, ethnic, cultural, educational and aspirational. In turn these may require a particular approach to delivering learning. For example, schools with a large proportion of students with English as a second language may need different curriculum support structures.

Social variety in schools relates not only to the backgrounds of students and staff, but also to an individual school’s particular pastoral arrangements. Typically a school may provide pastoral support in either ‘vertical’ or ‘horizontal’ structures. The former would include ‘houses’ incorporating students across the age-range of the school. The latter would include year or key stage groupings. Either may, or may not, have particular design implications, depending on the activities delivered within the pastoral groupings.

John Madejski Academy in Reading (WilkinsonEyre Architects) is a development of a BSF exemplar designvii, with discrete buildings linked by first floor bridges and a high level canopy. Each ‘strawberry’ shaped pavilion accommodates a separate house and includes science laboratories as well as general teaching spaces arranged around a double height central resource area.

Other things to consider:

- What are the pastoral arrangements in the school and what, if any, their design implications? Whether the school has a year, key-stage or house-based system, what activities occur within the group? Should each group have a defined physical location within the school, to enhance a sense of identity and ownership? How and where does registration occur and how many spaces are required? In what groupings are assemblies held and how often?

- How large a space or spaces are required for assembly? If large assemblies are required for multiple year groups, how is this space to be afforded within funding allowances? Perhaps associated spaces such as the main hall and drama studio can be amalgamated using a sliding folding partition to allow combined use for assemblies and performances.

- If the school has a sixth form, is it integrated within a vertical pastoral structure or is there a separate sixth form base? If a sixth form base is preferred, is this integrated with learning and private study spaces? Should it be located in a prominent position, for younger students to aspire to, or should it be on the periphery where it can enjoy discrete access?

- Dedicated indoor social spaces are not particularly well provided for under EFA funding arrangements. In the case of a secondary school, BB103 identifies only three such spaces – the dining area, sixth form social area (where appropriate) and staff social room. For a typical 8 form entry 11–16 school the dedicated social accommodation comprises around 335m2 or 3.9% of the 8,610m2 total funded area. Social use of other spaces is therefore crucial. How might these be arranged and configured to enhance indoor social provision?

- Dining is the largest social area allowed for under EFA funding. If it is only for dining however the space will be un-utilised outside meal times. Alternatively, can it be located and configured to accommodate other functions such as private study, small group work or other informal learning and social activities? Might it be combined with area allowances for assembly, using a sliding folding screen perhaps, to allow for larger school gatherings?

- How is dining delivered and in what groups? What is the take up of school meals? How many sittings are required or is a staggered lunchtime necessary? The latter may have a significant impact on design as different students will be learning and dining at the same time. Location and acoustic separation are therefore critical.

- Dining has a social function that extends beyond the physical necessity. How does this impact on dining provision, its location within the school and its style? Is the dining space a single homogenous area or is variety preferred? What about students who bring their own lunch? Where do they dine, with their peers or elsewhere? Where and how is drinking water to be provided within the school and grounds? Are fountains or bottle filling points preferred?

- If a defined external dining area is required, where should it be located and how is it to be managed? What about other external social spaces? Are areas to be defined for different age or other groupings? Are students to be allowed access to external sports areas (eg multi-use games areas or playing fields) for socialising and informal play?

- At what time do students arrive and leave school? Which areas are to be accessible before and after core school hours – the grounds, the LRC, or social areas including dining? Is a breakfast club to be provided and from what time? What are the implications on security and zoning?

- Is a faith room required? If so, should it be sited centrally or in a quieter, more peripheral location? Are particular facilities (eg ablutions) required? Might the space have a multi-purpose function?

- Does the school provide lockers and, if so, in what proportion to students? Are they to be centralised or dispersed? When are students to be allowed access to their lockers? Are they best located in registration areas, which may have restricted access, or in circulation spaces? Are external lockers acceptable or preferred?

- Where are toilets best located, for students, staff and visitors? Should they be separate or shared? Should they be centralised or dispersed? How are they best supervised?vii

- Does the school prefer a central staff social space (the traditional staff room) or is this function best dispersed into different areas of the school? If the latter, where are large staff meetings to be held? Should staff social and work areas be combined or separate?

- How will students be allowed access into the site and school buildings at the start and end of the day? Will they all use the same entrance or are multiple or separate entrances (for different groups) preferred. If the former, is the student entrance also the main visitor entrance? Might this cause problems for visitor access at peak times? If there is a sixth form, will they enjoy privileged access arrangements?

- Will particular social facilities (eg dining) enjoy extended or out-of-hours community use? Are there to be supplementary social facilities (in addition to school accommodation) and, if so, will the school enjoy use of these facilities during the day? How does this impact on their location within the school and will they require secure zoning?

Physical variety

While schools buildings might in theory be identical, all school sites are different; large or small; urban or rural; flat or sloping; developed or greenfield. All such differences will have a major impact on what is possible, both for technical and cost reasons. Understanding the opportunities and constraints of a particular site is therefore the most important first stage in developing a successful school design.

Large or small

Building Bulletin 103 provides formulae for appropriate site areas as well as for the gross building area required for mainstream schools of varying student populations. Where a site meets the minimum criteria, its size is unlikely to be a significant design driver, unless it is constrained in other ways.

BB103 recognises however that some school sites fall below the minimum guidance and suggests priorities for the provision of external facilities.

In these cases it will be important to maximise the net area available to students for curriculum delivery and socialising by minimising the nonnet areas (eg the footprint of buildings, entrance roads and paths, parking, drop-off, deliveries and refuse areas).

The space required for the footprint of buildings is inversely proportional to the number of storeys; the taller the building, the less its footprint. A multi-storey building is therefore more efficient in terms of land used than a low-rise solution. It is also likely to be cheaper to construct as the area of roof and foundations will be reduced. Within limits, a taller, compact building can also allow reduced travel distances and increase beneficial adjacencies.

On the other hand building high can have disadvantages that need to be balanced against the wish to minimise footprint:

- Primary schools in particular tend to prefer single or two-storey solutions, to minimise the risk of an institutional feel and to maximise direct connections between indoor and outdoor spaces.

- Secondary schools also tend to work best at three storeys or below. Beyond this, congestion on stairs can result in behavioural problems and the need for additional staff supervision. To avoid these risks (and ensure adequate fire escapes) a greater area is required for circulation, thereby reducing the efficiency of the building.

- Beyond three storeys, structural requirements can lead to increased costs over lower buildings.

On very tight, typically urban, sites however, taller solutions may be essential. It may even be necessary to use flat roofs for external sports or play-decks, or to excavate below ground. Where playing field areas are limited it may be necessary to provide an artificial turf pitch, as the area of these can be counted twice (in comparing to guidance) as it is possible to timetable them more intensively than natural grass pitches.

Urban or rural

The primary difference between urban and rural school design tends to relate to the available site area, as described above. There will also be differences in acceptable building heights however. In rural areas, planning considerations and impact on neighbours may limit height to one or two storeys. In suburban areas three storeys may be acceptable, in urban areas, taller still.

The non-net space given over to access may also vary considerably between urban and rural sites. In the former, the catchment area may be very small and transport connections excellent. In such situations the area required for parking and drop-off may be almost nil. In rural areas it may be extensive, requiring adequate space for buses as well as private cars.

Flat or sloping

Certain design solutions may be able to accommodate level changes better than others. For example, terraced or stepped designs can allow buildings to follow a natural slope while still providing an inclusive, accessible environment, albeit at the cost of earthworks and retaining structures. An incline can also help to minimise the perceived bulk of buildings, particularly those larger elements that do not require extensive daylight, such as sports halls, which can be cut into a slope. External amenity spaces can also benefit from an incline, helping to create distinct and varied areas as well as particular design opportunities such as an amphitheatre.

In contrast, the larger formal sports facilities such as playing fields and multi-use games areas (MUGAs) are restricted in their allowable gradient. For this reason it is sometimes necessary to consider their location first in order to minimise the need for costly re-grading. Once their preferred locations are identified, buildings and amenity areas can be designed on the steeper areas of the site, assuming these are also suitable for access, servicing and so on.

Developed or greenfield

One of the most significant constraints when redeveloping schools is the extent and location of existing buildings. Even when they are to be demolished it is usually preferable to build and occupy the replacement buildings first, in order to avoid the cost and disruption of temporary accommodation. This means that new buildings must be sited outside the footprint of the existing and in such a location as to allow safe and separate construction access alongside the functioning school. While a phased solution can help overcome this problem, it is likely to involve additional cost, time and disruption.

Where existing school buildings are to remain as part of the completed school, they must be integrated into the whole according to the same adjacency and access requirements as for an entirely new-build school, as further explored in Chapter 6.

In the case of greenfield sites such constraints do not exist. However other costs may be greater. For example, entirely new infrastructure may be required, including access roads, parking and service connections (eg drainage, gas, water and power supplies).

UCL Academy in Camden (Penoyre & Prasad) is located on a tight urban site alongside a new special educational needs school with which it shares certain facilities. The academy is accommodated over six storeys to enclose and shelter a lower-ground level courtyard. This main external space is supplemented by a series of roof terraces to maximise external social and learning opportunities.

Other things to consider

- Careful orientation of buildings can pre-empt or minimise environmental problems which are otherwise costly to mitigate. If possible, learning spaces should be orientated facing north (ideally) or south (as necessary). East and west orientations should be avoided if possible as the height of the sun in these directions varies most during the year, making it harder to control heat gain and glare. Though often overlooked, orientation is possibly the single most important factor in delivering a truly low energy design. Orientation with regard to views, sunlight and prevailing wind direction will also impact on the quality and use of external spaces.

- Many sites have noisy neighbours such as busy roads or rail lines. Wherever possible less acoustically sensitive functions should be located facing in these directions. Alternatively, facilities that require mechanical ventilation for functional reasons (eg science) can be sited in these locations, allowing other spaces to remain naturally ventilated wherever possible. Buildings may also be placed strategically to shield external areas from noise sources.

- While perimeter security is almost always a requirement, it is generally preferable for a design also to incorporate a secondary, inner security line for use during the school day. This allows visitors free access only to the public areas of the site including parking, drop-off and, crucially, the main visitor entrance into the building. Such an arrangement avoids the need for visitors to use an intercom at the site boundary and allows a more welcoming approach to the school.

- Service connections such as gas, electricity, water and drainage (both existing and new) can impose significant constraints and costs on any design. For this reason it is essential to carry out surveys at the earliest possible stage in the design process, including enquiries to suppliers.

Ethos, organisation and building typology

Reflecting a school’s particular ethos through its built form is one of the greatest challenges in developing successful school designs. It is partly a combination of functional preferences, as described previously, but it is typically more than the sum of those individual requirements. At its core is the ability to reflect a school’s style and organisation. For example, is the school outward or inward looking? Is it a single entity or is it the combination of distinct, identifiable parts; is it centralised or dispersed?

In identifying the appropriate form for a school, it is helpful to consider alternative typologies. While there is an almost infinite range of such models, four particular types suggest the full breadth of options, with hybrid versions in between.

Campus

A traditional model comprising separate buildings, each accommodating different functions or curriculum areas. The number of buildings may vary and students may need to move between blocks after every lesson or may be timetabled to one building for longer periods.

In recent years campus typologies have been less favoured than in the past. This is most likely due to the costs inherent in multiple buildings. A campus arrangement is however often a natural solution when adding new accommodation to existing schools.

The all-age Chobham Academy in Newham (Allford Hall Monaghan Morris) is designed for students aged 3–18 and incorporates three separate but linked buildings, each with a distinct form and visual identity. The arrangement of elements is designed to reinforce the new urban grain of the wider Olympics-led regeneration of the area.

Like all options, the campus arrangement provides both benefits and drawbacks:

- It is necessary to go outside to travel between buildings, although routes may be covered. Some schools consider this a benefit, providing students with fresh air and a chance to let off steam between lessons. Others consider such breaks a potential distraction to learning.

Lesson change may also take longer.

- In terms of building design, there is greater opportunity for variety. Each building can be designed specific to its particular function and with its own identifiable character. Each may also be sited in response to its particular functional requirements, such as proximity to external facilities or deliveries.

- A collection of distinct buildings affords landscape design opportunities and scope for creating different character areas in the spaces between.

- A campus arrangement can be particularly appropriate on a sloping site. Accessible level changes can be more easily and cost-effectively provided over larger distances in the landscape than within buildings. This needs to be balanced against the need for a lift within each block with an upper level. A larger number of fire escape stairs is also likely.

- Separate buildings naturally limit the potential for cross-curricular activities. There is a natural risk of ‘silos’ within the school and a reduced sense of the collective.

- Separate buildings do not allow one function or subject area to expand at the expense of another in response to changing demand.

- This model may lend itself to out-of-hours use of particular facilities. For this reason, and others, sports buildings are often separate stand-alone buildings.

Courtyard

Another traditional model based on collegiate precedents, themselves derived from the monastic tradition. The courtyard or courtyards provide an external focus for the school. A single courtyard arrangement is perhaps best suited to smaller schools, including primary. Larger secondary schools are likely to require multiple courtyards (which may be of different size, character and function) or a hybrid arrangement such as a central courtyard with ‘fingers’ arranged off it.

Barnfield West Academy in Luton (ArchitecturePLB) is arranged around a series of courtyards, each with a particular scale and character to suit a variety of external activities including socialising, dining and curriculum use. Views into the courtyards from the interior assist wayfinding, provide visual interest and allow generous levels of daylight.

Benefits and disadvantages include:

- Views into courtyards can help wayfinding and assist building legibility in a large school.

- Internal routes, as opposed to passing through courtyards, can be lengthy. Careful design, or a hybrid typology, may be required to avoid the need to pass through one curriculum area in order to reach another. This in turn limits ‘ownership’ and dual use of circulation spaces.

- The courtyard can be a valuable gathering space for larger numbers than are possible internally, potentially even the whole school. It can also provide a focus for engaging with the wider community, for example on open days.

- A courtyard arrangement can be used to provide a continuous ‘ribbon’ of accommodation, allowing particular areas to expand at the expense of others in response to changing demand.

- Any centralised layout, including courtyard arrangements, can be harder to extend if the school needs to expand.

Street and fingers

This model is based on a hierarchical circulation pattern and is included as one of the EFA’s baseline designs for secondary schools.

A generous ‘street’ provides the primary circulation route with distinct ‘fingers’ of accommodation arranged off it. The circulation street, which may be more or less linear, can be enhanced with area for other activities such as dining to create a generous and flexible multi-purpose space.

Street and finger arrangements became extremely popular in the recent school building boom. They are particularly appropriate for schools that wish to create identifiable sub-areas (for particular curriculum or pastoral groups) while maintaining the benefits of a single building. A common sub-category, the ‘hub and spokes’ model reduces the linearity of the street to a central atrium, with radiating fingers of accommodation.

Benefits and disadvantages include:

- The secondary circulation routes within the fingers are cul-de-sacs and as such, can be ‘owned’ and used by the areas they serve, for breakout from formal teaching, exhibition etc. Just as the street can be enhanced by dining or other functions, so can the secondary circulation within the fingers. This has led to the popular ‘strawberry’ arrangement comprising an open-plan resource area (often double or triple height) surrounded by formal teaching spaces.

- This model may be particularly suited to schools that enjoy extended use as it offers natural internal security lines, allowing general access to the more public activities in the street while allowing individual fingers to be locked off.

- The spaces created between fingers offer varied landscape opportunities. While some may relate to the activities within the fingers, others may relate to the street, providing routes to the outside or external dining.

- Because the finger blocks are arranged off the main street, each can be extended independently to allow for varied expansion where required. However, as each finger is separate from the others, it is not possible to rebalance teaching space between them in response to changing demand.

- While the separateness of the fingers promotes individual identity, it also naturally limits potential for cross-curricular activity.

The Jo Richardson Community School in Dagenham (ArchitecturePLB) is an early example of a street and fingers model. The three-storey street provides the main circulation and dining spaces as well as opportunities for informal assembly, small group activities and exhibition. Shared community facilities are located to the front of the building with the more private teaching wings to the rear.

Superblock

The superblock model provides a very compact arrangement and is also included as one of the EFA’s baseline designs for secondary schools. Typically three or more storeys, it is particularly appropriate on constrained sites where there is a need to minimise the footprint of the building.

The superblock model comprises a continuous ‘ribbon’ of perimeter accommodation arranged to encircle larger spaces in the centre. These typically include cellular spaces, such as the main hall and performing arts areas, and dining which is often full height and open to the surrounding circulation. This central atrium brings daylight from above into the heart of the building and acts as a focal point.

Benefits and disadvantages include:

- This is a very dense, inward-looking arrangement. Circulation can suffer from a lack of external views (as is evident in the EFA’s Baseline Designs) although this can be alleviated in some areas using single-loaded balconies around an open atrium. Such an arrangement also assists wayfinding by providing a strong visual reference point. In conjunction, the bottom of the atrium and the open balconies can accommodate large school gatherings.

- In larger secondary schools the ratio between spaces requiring daylight and views and those that can be internal (or rely on top light) is not ideal. As a result compromises are usually necessary with some of the former needing to be located centrally. This is easier to achieve if the school is happy for spaces such as the Learning Resource Centre (LRC) to be open-plan, in which case they can benefit from ‘borrowed’ light and internal views across the atrium. Open-plan dining at the base of the atrium may cause acoustic issues however, particularly if there is a staggered lunchtime.

- As a single building with limited external articulation, the superblock does not create defined, sheltered external areas in the same way as other typologies. Being less articulated it may be particularly appropriate in an urban street pattern where it all but fills the available site.

- The continuous ribbon of perimeter accommodation allows provision to be rebalanced in response to changing demand, while maintaining groupings. Combined with the centralised, inward-looking arrangement, the building form can also encourage and facilitate cross-curricular activity.

- The higher proportion of internal spaces limits the opportunity for natural ventilation. On the other hand, acoustic and pollution concerns may make this impossible anyway, particularly in urban situations.

- The EFA’s baseline designs illustrate a main superblock with a detached sports building. Such an arrangement can be ideal for discrete, community use of the school’s indoor and outdoor sports facilities. On the other hand, it isolates the changing facilities from performance and drama.

Thomas Fairchild Community School in Hackney (Avanti Architects) is a new school for up to 630 primary aged students plus a 50-place nursery. Arranged over three storeys to maximise the available site the building is a smaller example of the superblock typology with a top-lit central dining atrium providing daylight into the heart of the building.

Conclusion

Recognising variety and responding to project specifics is critical in developing designs that accurately reflect a school’s individuality and its particular circumstances, character and vision. The current trend towards standardisation however, combined with reduced budgets, increasingly proscriptive performance criteria and shorter design programmes, makes delivering bespoke solutions a real challenge. The combination of cost, quality and time constraints mean that it is essential to understand not only the school’s preferences, but also its priorities. Not everything will be possible, and efficiencies through standardisation in some areas are a necessary and valuable way of delivering school-specific solutions where they can have most impact.

It would therefore be wrong to suggest that standardisation is a bad thing in itself or that a highly individual design is necessarily better than a more generic one. In fact, the opposite can be true. If a design is too specific in focusing precisely on current requirements, then there is a real risk that it may limit scope for alternative patterns of use or future changes. There are cases, for example, of highly individual new schools briefed by a particular headteacher who then moves on, leaving a building that struggles to accommodate other approaches or different pedagogies.

In designing schools it is also important to recognise that a new building is not the finished product. Even in the short-term good school buildings need to be versatile, allowing staff and students to take ownership, experiment and change how they use space. In the longer term, a new building should also help the school to develop and improve over time. Above all, school buildings need to be robust, both physically and in the ability of the design to accommodate change.

Understanding and balancing these twin concerns, the specific and the adaptable, is the responsibility of the skilled educational designer. Whether standardised or bespoke, a successful design needs to offer a long-life solution, able to adapt to changing preferences and new requirements easily and efficiently.

References

i Refer Appendix 1.

ii The EFA is an executive agency of the Department for Education (DoE), responsible for funding education for learners between the ages of 3 and 19, and those with learning difficulties and disabilities between the ages of 3 and 25. They also fund and monitor academies, university technical colleges, studio schools, and free schools and provide building maintenance programmes for schools and sixth-form colleges.

iii Refer Appendix 2.

iv At the time of writing, guidance on the design of SEN schools is covered by Building Bulletin 102, although this is shortly to be replaced by a new Building Bulletin 104, currently out for consultation.

v Refer Appendix 1

vi As part of the Building Schools for the Future programme, the then Department for Education and Skills commissioned a series of exemplar projects. Published in 2003 as Schools for the Future - Exemplar Designs: Concepts and Ideas it is now only available online through commercial or subscription providers.

vii Toilets in schools are one of the most hotly debated subjects and of particular concern to both staff and students. Valuable guidance can be found in SSLD3 (see Appendix 1).

UTC Cambridge (Hawkins/Brown) required an innovative building to reflect their specialism in Biomedical and Environment Science. The brief was to create learning spaces to inspire students and prepare them for the real world. The architects brought their experience of designing for both industry and higher education to deliver ‘grown up’ learning environments and social spaces. In particular the top floor ‘superlab’ reflects the UTC’s specialisms providing bespoke and highly flexible laboratory space for up to 350 students.