6

The Complex Family Enterprise

THE TYPE OF COMPLEX family enterprise described in this chapter—a multigenerational, cousin-owned company that has reached a mature stage of business development—is a rarity among family companies. Probably no more than 5 percent of all family businesses in the United States reach this stage of development. Companies of this stature, however, have a unique importance in our model. The very fact that they have reached this stage means that they have successfully responded to challenges that scuttle other family companies. They contribute mightily to the GNP, employment, exports, and innovation in all market economies. The fact that they are more common in the older economies of Europe and parts of Asia suggests that they may be the future of some of the best of the post—World War II American firms, which are now making the transition from Controlling Owner to Sibling Partnership. They also represent many founders’ ultimate dream (or fantasy), which shapes the family policies of many businesses at earlier developmental stages.

These companies are among the icons of American commerce. Cargill, Inc., the largest privately owned company in the United States, is an example of a fourth-generation Cousin Consortium family business. Cargill’s product line, accounting for $47 billion in revenues, consists of commodities trading and transport, food processing and production, and agricultural products. The company has 63,000 employees working in forty-seven business units in fifty-four countries. Incredibly, 87 percent of the ownership, and complete voting control, still lies in the hands of three family branches, led by four cousins descended from the company founder, W. W. Cargill. The current CEO, Whitney MacMillan; his brother, Cargill MacMillan, Jr.; and two cousins, James R. Cargill and W. Duncan MacMillan, have run the business for the last twenty years.

Campbell Soup Company, another Cousin Consortium, is a $6 billion business that employs 47,000 people. Although its well-known soups control 75 percent of the domestic market, its other popular products include Swanson frozen foods, V8 vegetable juice, Prego spaghetti sauce, Vlasic pickles, and Pepperidge Farms baked goods. Four branches of the Dorrance family, including nine cousins and their children, control the company through their 51 percent ownership stake. The well-publicized dissension within the Dorrance family, in which one branch tried to force the sale of the company, illustrates one of the key challenges of managing these complex family enterprises.

Family businesses that have reached this stage must contend with considerable complexity in all three dimensions. The Cousin Consortium stage of ownership development not only suggests a larger number of individual family owners, but often includes trusts, holding companies, employee stock ownership plans, and even, in some cases, publicly traded shares. Although some of the business units have reached the Maturity stage of business development, other product lines, divisions, or subsidiaries are likely to be at other points. Finally, in the family dimension, the range of ages in each generation typically means that there will be different nuclear families within the clan in each of the family development stages, from Young Business Family to Passing the Baton.

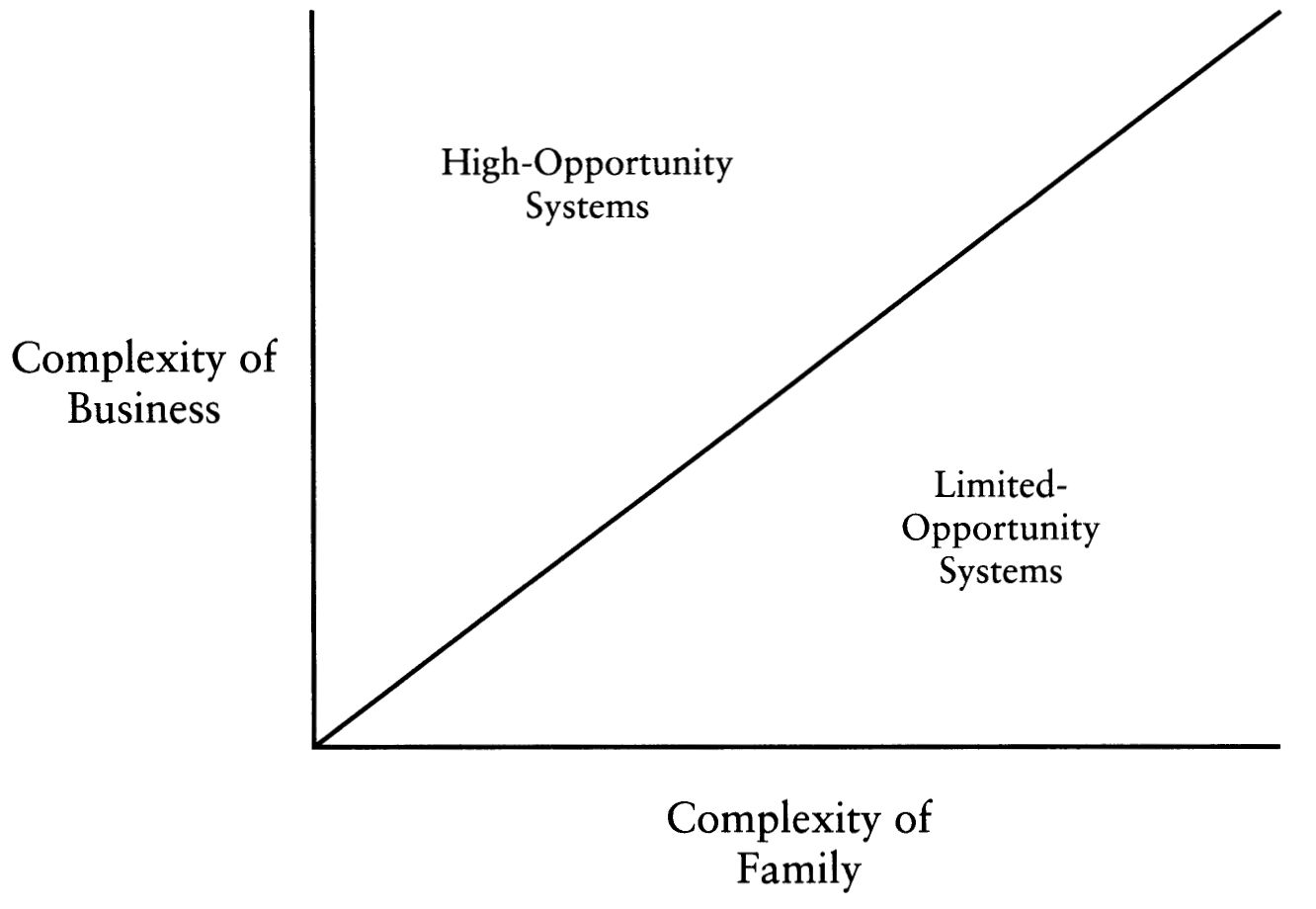

This increased complexity can be difficult to manage, but it also generates opportunity for family members and owners, which energizes the relationships among members of all three circles. As illustrated in figure 6-1, the relationship between family and business complexity creates for family members an environment of financial and career opportunity. In family business systems in which business complexity exceeds family complexity, sufficient “opportunities per family member” will be greater within the family business. These opportunities can be in terms of jobs, dividends, executive or board positions, compensation, and management development roles. More opportunities per family member helps to keep the peace within the family and keeps family members interested in and loyal to the business. Loyalty in turn helps the business to keep growing. On the other hand, when family complexity exceeds business complexity, opportunity per family member will be lower. There is greater competition within the family over scarce opportunities and less incentive for the entire family to be loyal to the business. Family companies need to learn how to accurately assess the degree of opportunity provided to family members in these complex Cousin Consortium systems, and how to manage the consequences. If the ratio suggests severely restricted opportunities, then either the business can be reviewed for its growth and renewal potential or consideration can be given to reducing the complexity of family ownership by pruning the shareholder tree.

Figure 6-1 ■ Level of Individual Opportunity in the Complex Family Enterprise

This chapter explores the typical issues faced by large, complex, dynastic family enterprises, focusing on the family business at the Cousin Consortium stage of ownership, with the core business at the Maturity stage and the dominant families in the Working Together stage of family development.

Hartwall Group Ltd.

Hartwall Group Ltd., a $400 million fifth-generation brewer and bottler located in Helsinki, Finland, is an encouraging example of a professionally run, complex family company. The company was founded in 1836 by Victor Hartwall, the great-great-grandfather of Erik Hartwall, the current managing director. Hartwall Group is structured as a holding company, totally owned by thirty-six Hartwall family members. The group in turn owns bottlers and brewers in Finland and Latvia, as well as a brewery machinery holding company in Holland. The principle products of the operating subsidiaries are several brands of beer for domestic and export sale, Coca-Cola and Schweppes products, and a variety of soft drinks and bottled waters. Since 1989 they have held a steady 67 percent of the Finnish beverage market, and they currently employ about 2,500 people.

The Hartwall family shareholder group has grown from one shareholder in the first and second generations, to three in the third, four in the fourth, nine in the fifth, and twenty-four in the sixth. There are three classes of stock: one nonvoting class, and both “strong” (twenty votes per share) and “regular” (one vote per share) voting classes. Some 10 percent of the company is publicly owned, nonvoting stock, which has provided the company with important capital for growth, but has not diluted family control of the enterprise. There are buy-sell agreements among the family shareholders, which control the distribution of the strong voting shares. Relatives are free to sell the regular shares. In the past, some shareholders were bought out to check the expansion of the ownership group, but there are no immediate plans to further “prune the tree.”

Through the first three generations, the company was controlled only by family members. Erik’s father, the fourth-generation leader, expanded the board to include nonfamily directors. Today the chair of the board of the holding company is a nonfamily member, as was once required by Finnish law and is now perpetuated by choice. Erik feels that differentiating the roles of chair and CEO has strengthened the leadership group, and he is eager to acknowledge the mentoring he has received from the non-family chair. The board is very active, meeting six to eight times a year. The board is credited with not only steering a sensible course for the company, but also allowing the nonemployed shareholders to feel that company actions are rationally arrived at and not just the desires of the management team.

Overall, shareholding has evolved so that no one branch has ownership control of the business. Three generations of shareholders are alive and very much interested in the company. In a culture that places a high premium on respect for seniority in the family group, this multigenerational work group has been able to interact in a cooperative, problem-solving manner; there is little visible competition within this closely knit group. Through several generations the family has followed the norm that reinvestment is a higher priority than dividends. Years ago, they established a formal limit on the amount of dividends as a percentage of earnings. Because the younger generation learns early that the company is not expected to be the sole financial support of the family, they pursue their own careers, in or out of the company.

Erik Hartwall leads the principal operating company as CEO. Erik’s family branch has been in management control of the company for three generations, but all four of the family branches are represented in the management of the company. Three fifth-generation cousins occupy key management roles, and an equal number of sixth-generation members have entered the company and are working their way up the ranks. At the initiative of the two generations active in management, the family recently began to respond to the challenges of the Working Together stage by clarifying employment expectations. To qualify for employment in the company, family members must complete their university degree, demonstrate that they have skills and interests that will contribute to the company’s performance, and express a long-term commitment to the company. An independent career psychologist counsels all sixth-generation members on their careers and deliberates with Erik and the board chairman about the suitability of potential family employees. Professional management standards are adhered to rigorously regarding all family managers.

In the last five years, as international competition has increased in Nordic countries as well as all of Europe, Hartwall has dramatically stepped up its already-respectable investment program. Following acquisitions of breweries in Latvia to increase its capacity, Hartwall completely reengineered its distribution system, including building a state-of-the-art warehouse at company headquarters. This new warehouse processes several times the volume of beer, mineral water, and Coca-Cola as the traditional warehousing system, lowering unit costs and providing faster information on sales. This innovation was complemented by a new management information system. Hartwall has not lost sight of what it is good at or how to make money. It has combined its tradition of strong customer relationships and market responsiveness with an increasingly analytical approach to decision making. In this way, the company has managed to fight off rigidity and bureaucracy and to maintain an entrepreneurial, professional spirit.

With all branches of the family represented in management, family members feel reasonably well informed about company performance and activities. But as the family grew, Erik understood that more formal mechanisms would be necessary to keep the family united behind the company. In 1991 he organized a family meeting to introduce family members to the academic topic of family business (they were well acquainted with the reality). At this two-day gathering, they instituted a representative family council. The council meets quarterly to plan for family meetings, develop family policies regarding the business, and discuss current issues facing the family and the company. The progressive approach has paid off. The younger generation in particular has appreciated being included in discussions about the business and having written policies about employment, promotion, and venture capital opportunities.

The long history of the Hartwall family has provided opportunity for each generation to learn from the mistakes and successes of its predecessors. Particularly in the last two generations, the family has been able to maintain an atmosphere of mutual support and respect, and has articulated family values that stress industriousness and modesty. The distribution of employment opportunities and ownership power reinforce a healthy balance among the family branches. Because there is little feeling of unjust treatment in the past and little sensitivity about being diminished in status now, family members express open support for one another and do not appear overly competitive. At the same time, they do not hide disagreements over policies or plans. In-laws have not had a fragmenting effect on the Hartwalls, in part because they have been brought into family discussions and are treated as first-class citizens in this system. The family works hard to stay aware of its internal politics and to maintain its family identity and support structure. This has been aided by the fact that the family is largely Helsinki based, and relatives see one another frequently in a variety of business and social settings. The family also no doubt benefits from the presence of leaders in the fourth generation who, now in their nineties, still appear at family gatherings to inspire even the youngest of the clan.

Ownership Issues

By the third or later generations, a business family can have grown quite large. Fifteen to twenty-five grandchildren in the third generation is not unusual; we have worked with several families with more than fifty members of the third generation, including grandchildren and their spouses. Later generations in dynastic business families may easily exceed one hundred relatives and in-laws. All of these relatives could be shareholders.

With most shareholders at this stage not employed in the business, nonemployed owners now have less direct information about company matters. Fewer family members now have a parent, sibling, spouse, or child to keep them informed and to guard their branch’s interests. To keep shareholders informed requires thoughtful information management—a requirement that, oddly enough, catches most family companies completely off guard. Getting enough of the right kind of information communicated to one’s family shareholders in a timely manner is no easy task. The task is made more difficult by three factors: geographic dispersion of the family (sometimes over continents); wide differences among family members in terms of skills, interests, income, and other factors; and the attitudes of different branches of the family toward the ruling coalition in the company.

As families grow and age, they become more diverse. Family members and branches differ in their incomes and income needs, wealth, social standing, political philosophies and affiliations, educational levels, careers, physical and mental health, and a variety of other factors. Most important, the branches of a family vary in their connection to and feelings about the business. By the third generation, one branch of the family generally has assumed management control of the business. The other branches will be more or less allied with this ruling branch. Often, another branch assumes the role of chief critic of the ruling branch. Typically, this critic’s role comes about because of feelings of being mistreated in the past; one generation’s sibling conflict can become a deep-seated antagonism between branches and cousins who may never have met. The “critical” branch is typically only marginally involved in the management of the company, if at all. It challenges the policies of the ruling branch and tries to get the support of other branches. This politicization of the ownership group is almost inevitable in Cousin Consortiums.

With or without a critical branch to galvanize opposition, family business leaders need to recognize that nonemployed shareholders have an important ownership and emotional stake in the business. They need to be informed of key events and have a legitimate right to a voice in the direction and policies of the company. The resolution of natural and created differences between the employed and nonemployed shareholders, between the ruling and critical branches, involves first recognizing the legitimacy of differing points of view. This is a difficult realization, especially if the family has operated under the belief that only those active in the business need to know about the sensitive issues in the company. In particular, if the family is organized in the Sibling Partnership stage into a quasi-parental system (as described in chapter 1), the transition to a Cousin Consortium may be especially difficult.

The key to effective management of shareholder issues is to develop a system of involvement and governance that informs and educates family members (shareholders and nonshareholders) and gives the family a real role and voice in the company, while shielding the business from the excesses of family politics and maintaining the business’s integrity. This lofty goal is, in fact, realizable through the efforts of a well-designed family council and board of directors. Boards at this stage generally include outsiders but still can be dominated by family members. This can work fine, or it can hobble the board if the family members act primarily to protect their branch’s interests rather than to look out for the general long-term interests of the business. Board structures that choose members only as representatives of family subgroups and without regard to their potential contribution to the real work that the board must accomplish generally work against both the business’s integrity and, ironically, family harmony.

Beyond the issues of family favoritism and inclusion, which are often present in these mature shareholder groups, both employed and nonemployed owners also tend to wrestle with the balancing act between dividend payouts to the family versus reinvestment needs of the business. As a family grows to this point, the number of family shareholders seeking dividend income will usually grow as well. The axiom we ask families to remember is “Families grow faster than businesses,” which is generally true. The family’s expectations about lifestyle have probably also grown, nurtured with each passing generation. The result can be a shareholder group that thinks first and foremost of its own personal financial needs and little of the financial needs of the business. It has taken the Hartwalls generations to come to grips with this dynamic and to find a way to manage it, but it still takes continuous reinforcement and reeducation of the younger generations about the limits on the company’s ability to support the family financially.

Balancing the financial needs of the business and family at this stage requires planning, a concern for both entities, a view that the business’s needs must come first, and a healthy dialogue between family and business members. Dividend policies must be established that allow healthy business reinvestment and give family members a predictable dividend income stream. Dividends may be traditionally high in some fortunate companies and may have high periods in many companies, but generally businesses cannot afford to sustain high dividends with a very large shareholder group. One role of leadership is to keep an expanding family’s dividend expectations realistic. Families must educate their members that the business will probably not be able to support them in the lifestyle they have seen in their parents’ smaller generation. As in Hartwall, family members must be encouraged to earn their own living and rely on dividend income only as a boost to their earned income.

If information to shareholders is not managed well or if shareholders feel their financial needs are not being fairly considered, the desire to sell out usually grows. Even when adequate and timely information and reasonable dividends are given to shareholders, some shareholders may not want to or be financially able to keep all of their shares. When this occurs, the ownership group must be prepared to buy out those who want to cash out all or part of their shares. A company may not be able to meet all shareholder demands for buyouts in a timely way. Long-term buyout agreements may need to be arranged to allow family shareholders to sell shares at a fair price and to help the company finance this activity. This, of course, necessitates the creation of a fair internal market (as discussed in chapter 3), where share price is agreed upon on a regular basis, typically annually.

To develop policies that protect the interests of the business, guard it from the excesses of family politicking, and treat the family fairly, nothing is more beneficial than a professional board of directors. Such a board should have ample nonfamily, nonexecutive “outsider” representation; we prefer to see a majority of outsiders on such a board. Family representatives on the board should be limited to the chair or CEO, the designated successor or successor candidates, and family council representatives. These structures and the relationships between them will be discussed in chapter 8.

Family Issues

Like any good Shakespearean play, the family drama at this stage of development has to do with its internal struggles over recognition, power, and money. By definition, families at the Cousin Consortium stage have at least two definable family branches and by the third generation can be very large. The largest fifth-generation family we work with, for example, has over 200 members. Families have a history, an accumulation of experiences, each of which is interpreted in a variety of ways within the family. The interaction of the family history with its current situation creates the context of family life.

Cousin Consortium families, really more clans than families, are political structures.1 Each branch and each family member has its own agenda. These agendas sometimes overlap and complement each other, and sometimes conflict. With each generation, a wave of in-laws joins the family, adding strengths and weaknesses to the skill base, sometimes helping to solidify the identity of the clan, sometimes diluting its identity, and certainly adding to the number of agendas the family will attempt to satisfy. To the extent that the multitude of agendas can be recognized and satisfied, the family can be satisfied and at peace. To the extent that the family company is seen as facilitating the satisfaction of family needs, the family can feel loyal to and proud of the business.

As noted earlier, by this stage one branch of the family has typically assumed dominance in management and may even include all the family members still employed in the company. In many cases the family is reassured that one branch is in firm control and that the performance of the company is not undermined by conflict fostered by uncertainty. This dominance structure can be welcomed by relatives who are glad that some family members are keeping the wealth and the commercial name of the family intact. But the way the dominant branch uses its authority will determine the reaction of the rest of the family. If relatives believe that the choice of successors, managers, and employees, and the resulting distribution of income, have unfairly favored the dominant branch to the detriment of another branch, resentment is likely to result. This is the situation that can lead to the emergence of the critical branch discussed above—nonemployed owners who try to reduce the power of, or unseat, the dominant branch. Similarly, the branch of the family most identified with senior management can feel misjudged by other branches and resent the lack of appreciation it feels it has received. When this occurs, family tensions can be magnified and carried on for years.

The general emotional fabric of Cousin Consortium families varies widely. Sometimes family members will retain a sentimental tie to the family of origin and, to some extent, have emotion-based relationships with one another, but the emotional residue from interactions in the past (as among siblings) has died down. Although still an important factor in family relationships, emotions in these families are based less on unconscious, early relationship factors and more on the satisfaction of current personal and branch needs. This calmness is most often the emotional tone of Cousin Consortiums where the rules for employment, dividends, and other policies have been in place for a long time, and the business continues to do well financially.

But, in other families, there is no sign of such a cooling out in the cousin generation. Because it is almost inevitable that the cousins have less intense daily contact as a group than their sibling parents did, and therefore less opportunity to have frequent current issues to fight about, a high level of emotional conflict at this stage usually means that old wounds to a branch’s pride are having a powerful impact on current relationships. Old wounds prepare a branch to see the current situation in a suspicious manner and expect to be mistreated by another branch. Individuals or branches who feel they have been unjustly diminished in the social order can feel great resentment. This resentment may be constant, or it can go underground for generations and emerge as covert or open conflict. Some senior family members go to great lengths to perpetuate old grudges through their (often-outdated) characterizations of other branches. Shortsighted members of the senior generation can, like effective whips of political parties, marshall support for their views and force their children to vote the party line. The junior generation of a business family must have great fortitude to defy the perceptions of the senior generation or to forgive past grievances and build solidarity among the family. This is why it is so important in every generation, if the family intends to keep a shared financial interest in the company after it has reached the Cousin Consortium stage, to reaffirm the identity and membership of the broad extended family outside the business, and to give younger generations a chance to gather their own data about more distant relatives.

For a family to have a sense of itself, it is necessary for it to have leadership. Such family leadership can be the same individuals as the business leaders when the family is united around the company and feels fairly treated. But it is often useful, and sometimes necessary, to encourage separate leadership of these two entities. The leadership of the family (one or more persons, none of whom must come from the senior generation) can help the family develop a mission that includes but extends beyond the business. Given the diversity of the family, it has a variety of interests outside the business that may include community, church, philanthropy, and other activities; the family may see value in acting collectively in any of these arenas. Even after several generations, the family may also share certain core values that help to define its identity; family leadership can help to articulate these and build a social structure around them. In chapter 8 we discuss the roles of the board and family council in balancing and expressing the needs of these critical stakeholders.

Business Issues

Companies that have reached the Maturity stage of business development have established their market reputations, grown beyond the cash flow crises of earlier stages to financial stability, hired professional management, and developed sophisticated management systems. Successful, mature companies are often dominant or at least very competitive in their market niches, having found ways to secure customer loyalty through cost or product advantages. This is the stage to which most family companies aspire, and for good reason. Once here, it is more possible to defend against competitive attack. A mature business generally has more leverage in dealing with suppliers, key customers, banks, and other resources. Once a business is large, it can gain the confidence of a market that can help it maintain momentum and grow even larger.

But size and maturity, like all organizational characteristics, also have potential disadvantages. Such businesses often run the risk of losing sight of two business basics they probably understood well in their earlier stages: strategic focus and market-smart innovation. Mature companies can begin to see their success as inevitable, rather than fragile, and stop listening to customers. They can close their eyes to current and potential competition and stop keeping up with technology. This turn inward generally spells trouble and sometimes is disastrous. Companies can stop innovating in ways the market appreciates and experiment with new products and services that are far from their core competencies. This loss of market focus and innovation can generally be traced to hubris on the part of leaders and to the rigidity and lack of responsiveness of a larger organization. Keeping the company responsive, innovative, and disciplined at this stage is the name of the game. Family companies are no different than other firms in this regard.

When companies reach this size they must guard against becoming rigid structures that discourage contact with the market and inhibit internal innovation. Keeping a business culture open and innovative is constantly challenging at any stage, but particularly when the company has been successful. A strong culture based on shared assumptions usually develops as a result of continued success. Organizational members are often reluctant to examine or alter these assumptions and, consequently, changes in the environment can transform these strengths into weaknesses. 2

Leadership Resources

Because the stakes of poor decisions are substantial, mature family companies must insist on management competence throughout the organization, including the board. Competence may come from inside or outside the family, but the company has no choice but to put the best talent possible in key management positions. Family leadership of a family-owned business builds customer, employee, and shareholder loyalty if it is competent. Competent nonfamily leadership of a family company is preferable to incompetent family leadership, but nonfamily leaders can have difficulty keeping all of the constituencies loyal.

The family at this stage faces a critical decision: Whether to exercise its leadership and control in the future through ownership or through management, or both. If the family chooses to remain an owner-managed firm, then leadership will need to be developed in both the board of directors, representing ownership interests, and senior management. If the family chooses to withdraw from management, then board positions become the vehicle for family control, and the management task becomes recruiting and integrating excellent nonfamily managers. Family members need not occupy the positions of both CEO and chair of the board. These positions are both very important for a business at this stage and have different orientations and responsibilities. As long as a family member can fill one of these two positions, the family will probably appear to have maintained its leadership of the company.

To maintain family leadership of the enterprise requires both attracting competent family members into the business and developing them for positions of high responsibility. In the Working Together stage of Cousin Consortiums, a plurality of the individuals from both generations will typically come from the same or close branches of the family. The primary challenges at this stage are developing credibility and authority (by the junior generation), preparing the junior generation for senior management, and preparing the senior generation to let go in the future. Preparing the next generation for senior management is both more straightforward and very challenging at this stage. The professional nature of the organization usually makes it obvious that clear standards of management competence will be applied to family members as well as nonfamily managers at this stage. The stability of the mature company also helps to define career paths that can lead the successful member of the junior generation to the top levels of the company. At the same time, the level of performance that the junior generation must demonstrate is now very high. All the stakeholders—the senior generation, nonemployed family owners, and senior non-family managers—will be less likely at this stage to support family managers who are not the best talent the company can attract for any key position. In particular, nonfamily managers may feel more secure as the company operates ever more like a publicly owned, professionally managed firm, and may demonstrate more open competitive behavior toward rising family managers. Family successors who make it to the executive levels in this environment have truly earned their stripes.

By the time a family has reached the Cousin Consortium and Maturity stages, even if family members fill the CEO role, they are no longer supplying most of the management talent to its business and it is unlikely that many family members are even employed in the company. At some point in its history, often by the third generation, a family business leader has “cleaned house,” removing family managers who contribute little and bringing in nonfamily to fill most management positions. If family norms prohibit such weeding out, then the company is almost certainly plateaued at a level of performance below its potential. Companies that reach the Maturity stage in this condition (sometimes prematurely abandoning Expansion/Formalization strategies) will gradually lose their competitive position and are candidates for eventual failure or acquisition. If they do survive to be passed on to the next generation, the chore of upgrading management will be dumped on the successors—a most difficult situation.

Capital Resources

Beyond the need for a high level of management competence, businesses at this stage require large amounts of investment capital to maintain, let alone advance, their interests. Annual investment requirements for maintaining plant and equipment are generally sizable, but can actually pale next to the investment needed for new technology, people development, and marketing programs. It is difficult to find a business dedicated to strong performance that does not have very substantial reinvestment requirements. Even service sector companies require sizable investments in training and development, management systems, and marketing programs. Few businesses today are exempt from these investment requirements. Mature businesses generally have even greater reinvestment requirements than do companies struggling to reach the mature stage.

Management’s view of investment needs is generally tied to its view of the market’s needs and the company’s vulnerability, as well as the company’s traditions regarding innovation. If management views the company as secure in its competitive position or the company does not have a strong tradition of innovation, little capital may be set aside for the future. The family’s need for income can also have a powerful impact on how much is reinvested in the company.

By this stage, the business will probably have encountered the question of being able to raise enough capital for growth without losing family control of ownership. We have pointed out several times that, by the time a business is mature, its capital requirements can be huge. Debt, when available, may cover only some of a company’s investment needs. The result is that many mature family companies must decide if they want to limit their growth to what they can support through internally generated funds and debt, or look outside the family for more equity capital. The two main options to raise growth capital are equity partners and a public stock offering. Each of these options will be evaluated in terms of the likelihood that they can raise the needed cash, and the consequences for family control. At this stage, family control does not necessarily mean owning a majority of the outstanding stock, or even the voting stock. These complex ownership systems may be effectively controlled in ordinary circumstances with a far smaller ownership share. But there is always some risk of nonordinary circumstances, where an effort is made to take control away from the family. Each family must assess its own comfort with various levels of risk, weighed against the capital needs of the company and the opportunity for significant increases in the total value of the shareholders’ equity.

One way to maintain the family’s control over the entire family enterprise while allowing outside investors into some areas of the company is to organize the family business as a holding company with subsidiary operating companies. In one design, the family members are sole owners of the holding company shares, distributed according to the family’s decisions about equity and estate planning. The holding company, in turn, is the majority owner of each of the operating companies’ stock. Outside investors (either a few individuals, or more through a public offering) also hold shares of the operating companies. In some cases, individual family members or branches also hold additional shares of those companies in which they have executive positions. This balance allows for spreading the returns of the whole enterprise throughout the family, but also rewarding superior performance for owner-manager family members on a company by-company basis. Ideally, each operating company has its own active board, including individuals from the family and outsiders who are most appropriate to that particular business or industry. Some holding companies put aside a portion of earnings as a “new venture” fund. This allows for family entrepreneurs to start and grow their businesses under the umbrella of the family enterprise.

One of the main objections to a holding company is that it can encourage undisciplined diversification. The extent of diversification is an important issue that often arises at this stage. Especially if the company has been successful, there is a desire to try one’s talents in new industries or geographical areas. A network of many different operating companies can provide greatly expanded opportunity for cousins to demonstrate leadership, satisfy an entrepreneurial need without leaving the family business, and have greater control over turf. It can also be a method of internationalizing a business, which can be essential for companies based in countries with limited investment capital and domestic markets.3 However, there is a downside risk if this process is not carefully evaluated and controlled. As many studies have pointed out, broad diversification can distract a company from its successful enterprises and dilute needed investment in profitable ventures.

A related issue that often emerges at this stage involves how to treat the original business, the business that launched the company and to which most of the family is quite attached. Often, by this stage, the original business has either begun to lose profitability or is well into the red. But because the family has a sentimental attachment to this founding business, there can be great resistance to closing, selling, or even reducing the size of this business. For the sake of the entire enterprise, the poorly performing business must often be “retired,” an act that sometimes involves a confrontation among family shareholders. Too often, closing or selling off the founding business is postponed to avoid family conflict, sometimes putting a drag on the entire company for years.

So that a mature business remains focused on its core competencies, the leadership of the company must form a compelling vision for the enterprise and convey that vision to a broad range of constituencies. After all, at this stage the company has many more stakeholders than just family owners and managers. There may be thousands of employees whose families are also dependent on talented leaders’ making wise decisions. There are customers and suppliers who count on their relationship with the company. And there is probably an entire network of community leaders, neighbors, recipients of company gifts or contributions, and future beneficiaries who may be relatively invisible to the business’s decision makers, but who would miss it badly if the company were to falter. Even if it is still completely in the family’s private ownership hands, the mature Cousin Consortium business is often in many ways a public resource. Guiding it is the kind of task that takes the combined efforts of senior management, the board, and the family council.

Somewhere in the mind of many of the entrepreneurs discussed in chapter 5, just founding their Start-Up/Controlling Owner businesses, lies a dream of the companies that are described in this chapter. These complex systems can be giants, dominant in their industries and well known to the general public. Family control may be very evident in the name and leadership of the company, or hidden and only apparent upon close reading of the annual report. In some ways their complexity and typical size makes their issues unique. In other ways, however, they demonstrate many of the same family dynamics and business concerns as all of their counterparts, who are less far along the developmental dimensions. There is still the tension between family control and broad participation in management and ownership, the dilemmas of continuity and succession, and the challenges of preserving the asset base while benefiting from it. Family companies that have accomplished the double tasks of building a profitable, competitive business while maintaining a viable and compelling concept of family should be justifiably proud.