7

The Diversity of Successions: Different Dreams and Challenges

SUCCESSION IS the ultimate test of a family business. Once the business has been transformed from an individual venture into a family enterprise, its continuity becomes a unifying concern. Inevitably, individual and company life cycles must diverge. Passing the company on, profitably and in good condition, to a new generation of leaders is a goal that drives the members of all three circles. This chapter addresses a fourth classic type of family business: those in which the ownership group, the family, and the company itself are within a few years of changing leaders.

Succession is not one thing but many. It is not a single event that occurs when an old leader retires and passes the torch to a new leader, but a process that is driven by a developmental clock—beginning very early in the lives of some families and continuing through the maturation and natural aging of the generations. Succession always takes time. Even in those cases in which sudden illness or dramatic events lead to abrupt changes in individuals’ titles or roles, there is a period of preparation and anticipation, the actual “handing over of the keys,” and the period of adjustment and adaptation.

The process, moreover, is not always as rational and planful as described in most of the family business literature. Some family businesses work hard to be proactive about succession planning and anticipate the preparatory tasks that accompany each stage of business and family development. Other families succeed by simply muddling through by themselves, without much conscious planning until perhaps the last moment. But whether elaborately planned or responded to as needed, succession is a complex process, presenting a formidable obstacle course for members of all three circles. The owners must formulate a vision of a future governance structure and decide how to divide ownership to conform with that structure. They must develop and train potential management successors and set up a process for selecting the most qualified leaders. They must overcome any resistance to letting go that the seniors may have and help the new leadership establish its authority with various stakeholders. And, after planning, strategizing, and negotiating, they must then be prepared to deal with unexpected contingencies, which may threaten these very plans at any point in the process.

Despite the great variety of structures that are actually adopted by contemporary family businesses (collective ownership, shared management responsibilities, multifamily succession), the family business literature has tended to remain focused on a single type of generational transition, in which a father passes his business to a son. This model, rooted in the ancient tradition of primogeniture and with practical advantages of clarity and predictability, is still a common form of succession. Nevertheless, the almost-exclusive attention given to it by the classic works in the field has tended to inhibit a true understanding of the complex universe of family companies.1

Lansberg has identified two core concepts that expand the traditional view of the succession process.2 The first core concept concerns the range of postsuccession options available to a business family and the fundamentally different processes involved in transitions to each of them. Some leadership transitions involve only a change in the people who are running the company, but others involve a fundamental change in the structure and culture of the company. The planning process can be likened to a journey that is shaped at every stage largely by the destination the family has in mind. In this case, the destination is the ownership and governance structure that the family envisions for the future of the company.

The second concept is that the choice of one or another structure at any given juncture is driven by a shared dream, in which the aspirations of individual family members become woven together in a collective vision of their future. Members of the senior generation have individual dreams of the company and the family after they are gone. They may see the company as a monument to their own accomplishments, with new leaders replicating their successes in a replay of the seniors’ tenure. Or it could be a very different vision, correcting all the seniors’ self-perceived mistakes. Each person in the junior generation will also have a vision, including a fantasy about his or her role, and the hoped-for network of relationships with all the other members of the rising generation. The ideal process of succession planning is the gradual uncovering of these individual dreams, and their integration into one goal and one course of action.

Reaching that ideal is not always easy. The individual dreams may be vastly different and even incompatible—as when the retiring leaders want to maximize continuity and the aspiring leaders are committed to dramatic change. Further, as the shared dream takes shape, it may or may not be realistic when matched with the “raw material” in the family; that is, the distribution of skills and talents in the next generation. The implementation of the dream may be hampered by the authority and influence hierarchy of the family, with the most powerful individuals favoring a solution different from the majority’s. Finally, families that envision a structure different from the one to which they are accustomed often have not considered the implications of the change and the fundamental transformation of the business culture that will be required. However, all family members are driven to some degree by the shared goals of success, financial security, and fulfillment for their offspring. When these positive forces outweigh the impediments, succession planning has a fighting chance to succeed.

This chapter illustrates the process by which a shared vision of the company’s future emerges and guides the transition from one generation to the next. Although succession is a process in all three circles, we have found that the transition mechanism in family business tends to begin with choices about ownership. In large public companies in which ownership is not dominated by one family or group, the stock is so fragmented that senior management has de facto control over the business’s direction.3 There, succession is about changing the CEO, not about trading stock on the exchange. But in family businesses, even if management has been passed largely to professional nonfamily executives, the family’s control of ownership marks the seat of ultimate power in the system.4 It is the often-evoked golden rule of family business: “The one who has the gold, rules.” As a result, the succession process begins with decisions about the ownership form for the next generation—Controlling Owner, Sibling Partnership, or Cousin Consortium—and those decisions serve as catalysts for the other transitions in management and family leadership. For that reason, we have organized our presentation of the succession process by describing the transition toward each of the three ownership stages.

The following case is an excellent illustration of the succession process, because it describes two separate leadership transitions, one recently completed and the second already well under way. The experience of the Lombardis, a sophisticated and competitive family with a successful business, illustrates the challenges that must be dealt with as a company moves from one governance and leadership structure to another.

Lombardi Enterprises

Lombardi Enterprises began as Lombardi Foods, a small-scale produce distributor in the Sonoma Valley. Today it operates a $900 million chain of retail markets throughout the western region, specializing in gourmet items as well as the usual array of grocery products. The founder, Paul Lombardi, Sr., came to the United States from the Tuscany region of Italy and started operating a few acres as a truck farmer. He built the company and ruled it as a controlling owner for almost twenty-five years; now he is eighty-two years old and retired. For the past twenty years, the company has been run by his five children, four sons and a daughter. The oldest—Paul Jr., fifty-five—has filled the role of “first among equals” in their Sibling Partnership.

Over those twenty years, there has been a transformation in the management style and culture of Lombardi Enterprises. During Paul Sr.’s long tenure, power and authority radiated from a single source. Decision making was concentrated in the hands of one leader, who also enjoyed most of the glory for the company’s successes. Under the Sibling Partnership that has emerged since his retirement, major decisions are made by consensus. Paul Jr.’s role is much more circumscribed than that of his father. Over time, he and his siblings have worked out a system in which all grant one another a certain amount of autonomy in running their divisions, and no one individual captures all the limelight. Nonfamily managers have had to adapt to a wholly new management environment, in which authority flows not just from one but from five sources and decisions at the top are often made by a group.

The first leadership transition at Lombardi Enterprises demonstrates how a near-tragic event can precipitate a fortuitous succession. While swimming at a California beach in 1977, the athletic founder was caught in an eddy, dragged down, and nearly drowned. Paul Sr., then sixty-two years old, spent almost half a year recuperating in a hospital and remained depressed for some time afterward. Meanwhile, Paul Jr. and his siblings stepped into the breach. Proving the dictum that power is seized and not given, Paul Jr. not only filled the leadership vacuum but, in a short time, was leading the company into new ventures. By the time Paul Sr. returned to the company, it was clear that members of the second generation were fully in charge and running things smoothly. The father decided it was a good time to step aside and assume an advisory role as chairman of the company.

It would be a mistake, however, to think that this first succession was entirely unplanned—or that it took place instantaneously. From the time the five Lombardi siblings were young, Paul Sr. and his wife, Anna, had envisioned that the children would one day take charge of the company and manage it as a team. In those early years, the parents tried to dampen their offspring’s natural competitiveness and encourage them to cooperate and share, with the idea that teamwork would eventually be essential to their future partnership. When stock was transferred to the second generation, each sibling received an equal amount. The five now control 55 percent and will inherit the rest after their parents’ deaths.

The five were well prepared for company leadership. The four sons were sent to excellent colleges and then graduated from top business and technical schools. As head of the company’s markets division, Paul Jr. has demonstrated his leadership by expanding the supermarket chain from twelve California stores in 1965 to sixty-five stores throughout the West and Pacific Northwest in 1990. The only sister, Rita, is also college educated. She has traveled widely and for many years headed the company’s import division. Each of the siblings had been working in the company for several years and was in charge of a division when their father’s accident occurred.

It has taken years, however, for Paul Jr. to consolidate his position as leader of the sibling system. His position as first among equals was a compromise that preserved some of the appearances of his father’s strong individual leadership and made the participative system more acceptable to employees and the outside world. But Paul Jr. had to gradually legitimize his leadership with his siblings, and the scope of his authority has been defined over the years by trial and error. When Paul Jr. makes a major decision without informing them first, they let him know—very pointedly—that he has exceeded his authority and that, as equal partners, they expect to be consulted. After many years of defining the boundary ad hoc on each new occasion, the partners have recently attempted to define explicitly the boundaries of the oldest brother’s authority. So, for example, the partners have agreed to let the CEO make decisions on any expenditure of money below a certain amount and on ventures that do not commit the company to support for longer than two years.

The Lombardi siblings have been willing to grant certain limited powers to their oldest brother because he has proven his ability to put money in their pockets. In recent years, they have recognized Paul Jr.’s need to receive more recognition for what he has achieved for the company and have been more generous with their private compliments and public credit. Nevertheless, if Paul Jr. gets too bossy or tries to act like the patriarch in any decision, they are quick to remind him of his limited powers.

Even as Lombardi Enterprises reaches closure on the first succession from Paul Sr. to the Sibling Partnership, it is moving toward a second that will be even more complex to manage. Paul Jr. has suffered a mild heart attack and, at fifty-five, is thinking of retiring soon. The sibling partners are thus at a crossroads where they must decide when the next leadership transition will occur and how the new leader or leaders will be chosen. The partners could have chosen to recycle the present structure, giving each sibling who wants it the opportunity to serve as first among equals, but they have rejected this option. Perhaps because none of the four wishes to take over the CEO’s job in the shadow of the successful oldest brother, they have decided that the next change in leadership will occur when members of the third generation are prepared to take charge of Lombardi Enterprises. There is already some evidence of sibling politics. The sibling partners worry that Paul Jr. is maneuvering to position his son, Jaime, the oldest of the cousins and the one with most experience in the company, as an automatic choice for CEO.

There are twenty-five cousins in the third generation, many of whom have already expressed their commitment to the company’s tradition of professionalism. They have also revealed an eagerness to take places in top management. The hard reality is that not all who want to make careers in the company and aspire to top positions can be accommodated. The seniors are thus faced with some tough decisions that the family has never had to deal with in the past. What will the requirements for entry into the company be? Because the cousins vary much more widely in age than did the siblings, how will the choice of leaders be affected by the fact that some will be old enough to take over before others? Moreover, there are more cousins in some branches of the family than in others, which raises questions about how stock should be divided. If each sibling divided his or her equal share among the offspring, some cousins will end up with many more shares than others. On the other hand, if stock is to be distributed equally to the cousins regardless of their branches, it would require a buyout process. Given that some branches would then control more stock than others, how would that affect the balance of power in the next generation?

The list of decisions that must be made is formidable. If some cousins who aspire to work in the company will not be able to get jobs, what, if anything, should the family do to support the careers of the disappointed family members? If many will be passive shareholders, what will the family managers of Lombardi Enterprises have to do to ensure their continuing support and loyalty? The growth in sheer numbers of shareholders in the third generation will also put financial pressure on the company to provide a steady flow of generous dividends to cousins not making careers in the company. Can Lombardi Enterprises enable the cousins to maintain the affluent lifestyles to which they are accustomed, without depriving management of the capital it needs to build the company?

The biggest challenge in transitions to a third generation is to set up structures to manage all of this complexity. The biggest risk is that the sibling partners will attempt to install a structure very similar to their own. In other words, they may look for a group of cousins who can work together and continue the same pattern of shared decision making that they have been able to establish. But this vision of the future probably will not fit the changed circumstances in the third generation. The kind of mutual understanding and synergistic cooperation that siblings growing up under the same roof are sometimes able to achieve is difficult to replicate in the third generation; cousins grow up in households and families that may be far apart in values and attitudes.

The seniors have other options, however. If managing complexity becomes too difficult, they might ultimately agree to return to a Controlling Owner form—under which one family would very likely have to obtain a controlling share of stock through a buyout process. This alternative would be particularly attractive if one of the cousins emerges as an outstandingly qualified leader, head and shoulders above his or her contemporaries. Or the Lombardis could conclude that, if only a few are chosen to lead, that will create bitter feelings and divide the five families. To avoid that, they might decide to go further down the road of professionalizing the business by hiring nonfamily managerial talent to take over the top executive positions. Again, these choices may not be arrived at by an entirely rational planning process. They may be the result of subtle negotiations and compromises. Whatever ownership and governance structures are chosen, however, structures such as a board of directors with qualified outsiders on it and a family council in which nonparticipating members can discuss business matters that affect them will be essential to ensuring sound, professional management and shareholder harmony.

How the Shared Dream Is Negotiated

At the heart of the notion of planning is the idea that the family can create a blueprint for the business, which will describe its future strategic direction as well as the ownership and governance structures of the organization. Long before details of the blueprint can be filled in, however, the family members need to formulate a shared dream—an energizing vision of what the company is to become that will enable the family to realize all of its individual values and aspirations.5 This concept of the shared dream is Lansberg’s adaptation of the dream concept introduced in Levinson’s work on adult development. In his research in the 1970s, Levinson described the dream in the lives of his subjects as “a vision, an imagined possibility that generates excitement and vitality. . . . It may take a dramatic form as in the myth of the hero: the great artist, business tycoon, athletic or intellectual superstar performing magnificent feats and receiving special honors. It may take mundane forms that are yet inspiring and sustaining: an excellent craftsman, the husband-father of a certain kind of family, the highly respected member of one’s community.”6

Entrepreneurs and their spouses are typically driven by a powerful dream that influences the way they bring up their children, as well as the operation of the business. The shared dream usually begins to take shape when the children are young. Their parents develop a vague longing to see all they have built survive and continue after them, to provide sustenance for their families and their fundamental values. Meanwhile, their offspring are growing up in the pervasive shadow of the family company, which inevitably becomes a force in their lives, shaping their own aspirations and career choices. The juniors may decide to reject the seniors’ dream and pursue their ambitions outside the family business—usually not without great psychological conflict. Or they may decide that they can realize their own ambitions and values within the family business. The process of forging a shared dream turns into a negotiation that begins in early dialogues between parents and children and continues right into the adult years, becoming more urgent and explicit as the time for a leadership change approaches.

For families that manage to forge one, the shared dream is thus a vision of the future, which all family members can enthusiastically embrace and which forms the basis of their future collaboration and provides the motivation and excitement needed to carry the family through the hard work of planning. Often it has a religious inspiration or stresses a social mission beyond profit making. However, not all families have a clear idea of what they want for the future of their families and the business. And in some families, the parents have dreams that are contradictory; for example, if one favors a system of equal owner-partners and the other wants to give ownership and control to only one child. When parents have a clear and congruent dream, it influences the way they raise their children as well as how they train the next generation to take over the leadership. When parents have contradictory dreams, however, they may avoid open discussion of their differences and send confusing signals to their offspring. Some couples discuss and reconcile their dreams as they form their marriage enterprise in the Young Business Family stage or as they revise it in later stages. Some families confront the inconsistencies in their dreams as they deal with the younger generation’s initial life planning in the Entering the Business stage. Others completely avoid the process of negotiating a shared dream with the younger generation.

As the offspring grow into adults—and clarify their own dreams—the family’s shared dream may have to be revised. The seniors must clarify for themselves the structure they want for the future and constantly reassess whether the talents, skills, and commitment of the juniors are strong enough to make that structure work. Likewise, the juniors’ career interests evolve as they grow to maturity and experience the world and the family business. The dream of a sibling structure, owned and managed by equal partners, may have to be abandoned, for example, if only one offspring is interested in joining the business, or if only one is clearly qualified to lead it. Indeed, if none of the next-generation family members aspires to a career in the business, the owners may have to decide whether it would be feasible to hire nonfamily managers to run the company or consider selling it.

Families that aspire to a different governance structure than the one they have always known face a cognitive leap of faith. The three basic forms of governance—Controlling Owner, Sibling Partnership, and Cousin Consortium—call for very different leadership styles and structures. Business owners often cannot realize the full implications of the choice they have made, because they are unable to evaluate the evidence regarding what kind of structure is feasible for their family. That is not surprising, for the only roadmap they have is their own experience—the roadmap that has guided them to business success—and the terrain that lay behind may be quite different from what lies ahead.

Understanding the Diversity of Successions

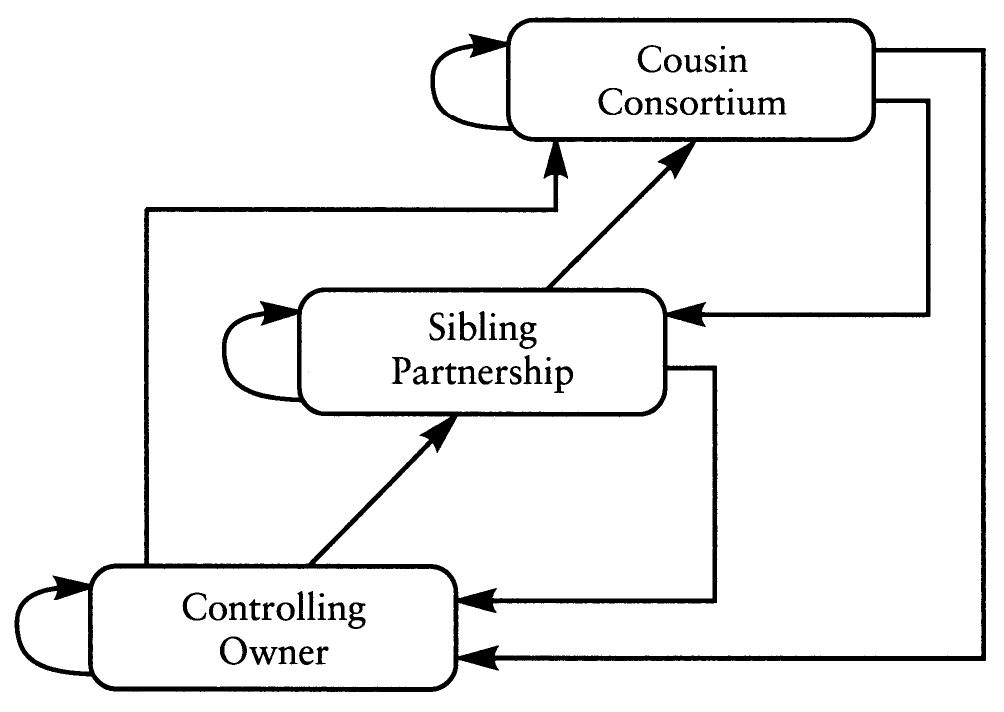

In describing the ownership developmental dimension in chapter 1, we presented three categories of family business ownership: Controlling Owner companies, Sibling Partnerships, and Cousin Consortiums. Typically, when a company is on the brink of a leadership transition, the choice of a future governance structure involves three basic options. The first is to recycle the structure that has worked during the tenure of the incumbent leadership, as when a founder leaves the business to one daughter or son (Controlling Owner to Controlling Owner) or when a group of cousins passes on ownership to their children (Cousin Consortium to Cousin Consortium). The second option is to move to a more complex structure by dividing ownership rights and management responsibilities among a group of next-generation siblings, as was the case in the second generation at Lombardi Enterprises (Controlling Owner to Sibling Partnership), or when siblings pass on ownership to all their offspring (Sibling Partnership to Cousin Consortium). The third is to make the future ownership and governance structure simpler, which would be the case if, for example, the Lombardis were to return to a single owner-manager in the third generation (Sibling Partnership to Controlling Owner).

Many family business owners approaching retirement do not fully appreciate the range of choices open to them. As we discussed in chapter 1, successions in family businesses do not have to follow a progressive sequence from simpler to more complex. Many family businesses, for instance, are founded not by a single entrepreneur but by a team of siblings. In the second generation, the siblings may choose the Controlling Owner form as most feasible, with the successor and his or her family buying out the other partners’ shares. A comparable change can happen in a Cousin Consortium, when cousins decide to sell their interest in the family company to a cousin in one branch, who then becomes the controlling owner. By the same token, a Controlling Owner business may skip the Sibling Partnership stage entirely and go directly to a Cousin Consortium. This rare type of succession occurs when none of a controlling owner’s children is interested in or capable of leading the business, and the owner-manager thus makes plans to transfer ownership to his or her grandchildren, in the hope that they will eventually be able to take it over. (Usually in such cases, the owner-manager hires nonfamily professional “bridge managers” to run the company in the interim.)

Figure 7-1 shows a total of nine possible types of succession. Three are “recycles,” involving a change in leadership while maintaining the same ownership form; three are “progressive” successions that involve a change in leadership while increasing the complexity of the ownership form; and three are “recursive” successions that involve a change in leadership while simplifying the ownership form. This typology demonstrates the true diversity and complexity of leadership transitions. When succession involves replacing the leadership without altering the basic form of the business, much of the owners’ accumulated learning from the past is applicable to the future. However, when succession involves not just a changing of the guard but a restructuring of the fundamental form of the business, the adaptation required of the system is of a higher order of magnitude. In this case, little of what may have worked in the past is likely to work well in the future.

Figure 7-1 ■ Nine Types of Succession

All successions in family companies involve the passing of a baton from one generational leader or team of leaders to the next generational leader or team. The tasks that must be accomplished before the senior generation can depart and the junior generation can take charge, however, vary significantly, depending on where the transition starts and where it is designed to finish; that is, the governance structure employed by the seniors and the structure envisioned for the juniors.

The Transition to a Controlling Owner Business

The idea that one and only one individual should be the leader is steeped in the rich imagery of the hero in Western culture. (Given the historical biases of Western culture, the hero myth is traditionally presented as male. In the contemporary world, it obviously applies to both genders.) The king passes the crown to the crown prince. Likewise, the lord of the manor, to prevent his land from being broken up into uneconomic small holdings, turns it all over to one heir. The master’s skill and craftsmanship lives on after he has gone in the apprentice to whom he has vouchsafed his sacred knowledge and secrets. It is perhaps natural for an entrepreneur, who has performed the great deed of starting a successful business and personifies this company in the community, to want to see his or her name and work carried on by a favored child who promises to become a hero in the founder’s own image—to family, to employees, and in the community. There can be an intense identification between the controlling owner and the chosen son or daughter (or, in some cases, the chosen nephew, niece, or child-in-law).7 To the extent that the senior has not achieved all of his or her own dream, he or she sees the successor as completing the holy quest. It is the ancient fantasy of immortality, to transfer one’s experience and self from the aging body nearing the end of a life into a youthful and energetic figure who will continue the work.

One-person, monocratic rule also has deep roots in the hierarchical traditions of both church and state. From the management point of view, it has the advantage of being parsimonious. It permits decisive action, often critical when a company must move quickly to capture markets or beat competitors. By contrast, rule by committee is often slow and cumbersome. Controlling owners tend to believe that it is their ideas, their willingness to take risks, and their decisiveness that accounts for the company’s success—and that groups are inherently incapable of those qualities. In addition, the outside world, including customers, lenders, and community organizations, is still more comfortable dealing with one individual than with a group.

Paradoxically, when the controlling owner has unshared control of both ownership and management, the very advantages of this form of governance, monolithic decision making, are also its biggest drawback. With a Sibling Partnership or Cousin Consortium, families spread the risk by placing ownership control in the hands of a group of offspring. Families that choose a Controlling Owner structure for the next generation are betting the store and the family fortune on the leadership talent, business acumen, and emotional maturity of one person—a risk that is magnified if the controlling owner is also the CEO. A poor choice can have grave consequences for the business. Moreover, the decision to have only one leader increases the risk that the choice of a son or daughter will be based on emotional favoritism rather than on demonstrated competence.

Probably the most common situation that leads to a recycling succession to a Controlling Owner form is when there is only one offspring, or at least only one who has any interest or expectation of being either a manager or an owner in the business. In the case of the single heir, there will still be the challenges that come with any intergenerational transition, but making the choice of successor is not part of the problem. By far the more complicated cases occur when there is more than one next-generation member who has an interest in the business. In those situations, when families opt to continue or return to a Controlling Owner structure, they need to devise a mechanism for concentrating the stock in the single successor’s hands. For those families in which the business is the primary asset, this raises fundamental questions of fairness in distribution of the family’s wealth. Parents who want to avoid showing favoritism among their offspring are strongly inclined to divide stock in the family company more or less equally among members of the next generation in a Sibling Partnership.8 Choosing a Controlling Owner model usually means that this equal division idea has been overruled by the principle, emphasized by Danco and other advisers in the field, that the one responsible for leading the business and producing results must control the stock.9 Otherwise, the chief executive’s decisions can be constantly undermined by dissident shareholders.

Sometimes parents in a Controlling Owner generation try to hedge this issue by investing management seniority in one offspring, but dividing ownership among the sibling group, and instructing them (explicitly or, more often, with unspoken assumptions) to support the business leader “as if” he or she were a controlling owner. This is often an untenable resolution. This point was driven home by a second-generation owner-manager who had worked in his family’s business for twenty years. When his parents died, they left the stock divided equally among him and his four siblings. This man complained bitterly about the injustice of the parents’ decision.

It was always understood by all that I was the one who was going to take over the family company. I loved working with my parents. I put in the time, I made the effort and achieved the respect of all employees. My parents had always led me to believe that I would control the company. However, shortly before their deaths, they felt that giving me majority control was going to be unfair to my brothers and my sister. Without telling me, they changed their will and left us all equal shares in the business. I now feel like an ox pulling the rest of the family along. The irony of it all is that they thought this would minimize the conflict among us.

It is better for members of the senior generation to be clear in their own minds about whether they want all or nearly all of the ownership shares to go to a Controlling Owner successor, where concurrence and participation of other minority shareholders (if there are any) is unnecessary, or whether they want to consider some form of Sibling Partnership, where collaboration is required. The parents’ dilemma in choosing a single successor is that, while denying control of the stock to the next generation’s business leader may ultimately hurt the business, concentrating the stock in the next owner-manager’s hands can divide the family. Even in families that understand the distinctions between the circles, a position of authority in the business usually endows the incumbent with great power and prestige in the family as well. The elevation of one brother or sister in a group of siblings to be the controlling owner, even when other family assets more or less equalize the estate plan, can exacerbate jealousies and rivalries that go back to childhood. The controlling owner sibling’s control of the business can create a de facto quasi-parental situation in the family (as discussed in chapter 1). Some older siblings already had a quasi-parental role in the early years of a family, but it normally weakens somewhat as the younger offspring mature. If given control of the business as an adult, the older sib can easily slip into a parental role again. This may be bitterly resented by the other siblings. Consider how a brother or sister will feel if, instead of going to the parent to request a loan, he or she must go to the sibling who has been named controlling owner of the business.

In certain ethnic cultures, where the rule of primogeniture persists most strongly, an oldest son is still more readily accepted as a single owner-manager than a younger son or daughter. With more daughters as well as sons desiring leadership roles in family companies today, the choice of a single successor may lead to a head-on collision between older ideas of the family “pecking order” and the new standards. Barnes, for example, has written about the problems created by what he calls “incongruent hierarchies” in modern families. If daughters and younger sons tend to rank lower than older or eldest sons in the family hierarchy, for example, but one of them becomes the CEO, “the incongruence is obvious . . . (and) can lead to family stress that becomes even more painful when older siblings are actively involved in the business.”10

If the senior generation is firm in its commitment to a Controlling Owner succession, the system’s acceptance of the decision can be greatly facilitated by educating the other family members, as well as additional stakeholders in the company and its network, of the reasons for the choice of the Controlling Owner dream, and the process by which the successor was chosen. The family leaders do not need to justify their decisions in a defensive manner; the golden rule is operative here. However, explaining the decision by explicitly describing the values and priorities that underlay it can help prevent the business ownership decision from leaving the younger generation irreconcilably divided in the family circle. For example, if a current controlling owner is able to say, “Our best prediction is that the business is headed for a very difficult period, with restructuring and downsizing likely, and I believe that it is essential for one owner to have unfettered control and responsibility for the leadership ahead,” or, “I made a promise to my daughter when she started in the businesses that if she dedicated herself to preparing for the role, I would turn the company over to her in time,” a dialogue can begin, which can help the family accept and prepare for the new arrangement.

The same dilemma about how severely to consolidate ownership control must be addressed in choosing whether to exclude family members from management, choose only a single family executive, or invest in a family management team with many next-generation members participating. Forming the ownership dream for second and later generations based on a Controlling Owner instead of Sibling Partnership structure usually implies a similar decision about management in the business—that is, that the family has already identified or wants to identify one executive leader for the company. In some family businesses, the choice is easy. S. C. Johnson & Son, makers of Johnson’s Wax and the insecticide Raid, have had a single family member in control of ownership through four successions. Samuel C. Johnson, the fourth-generation CEO, has written, “Our firm has been fortunate in that there has been one logical successor in each generation.”11 But this is not always the case. If several more or less equally talented siblings aspire to be leaders, the choice of a Controlling Owner structure sets up a winner-take-all horse race. The more restricted the access to senior roles, and the longer the choice is put off, and the more ambiguity there is about the candidates and their relative standing, the fiercer the competition for the owner-manager position can become.

All family members know that their collective and individual futures depend on good choices. However, each generation, and to some extent different members of the generations, may have different points of view on the best process, guided to some extent by their different agendas. The senior-generation leadership is likely to want to delay the choice until one candidate emerges as clearly head and shoulders above the rest. This may require sufficient time for all of the candidates to be tested in varied positions. However, the parents of the older or leading candidates, who have a head start on experience and seniority in the company, may be more in favor of a faster timetable. In the same way, the members of the junior generation who see themselves as in the lead will emphasize early commitment and experience as critical criteria and may remind the decision makers of the disruptive effects of prolonged competition. Younger or “fringe” juniors may emphasize the value of a rational, objective process, protected from family politics and long enough to ensure that the right choice is ultimately made. Whatever process and timetable are chosen, the “tournament atmosphere” can be disruptive to ongoing business operation and put considerable pressure on the current owners.12

Some parents who want to put the company’s future in the hands of only one leader simply put off the decision because they are unable to pick one of their offspring over the others. This is a particular problem in enmeshed families, whose members have such close and intense relationships that the parents fear that any act that can be construed as favoritism will shatter family unity. There may, in fact, be a variety of reasons why a parent is not willing to set up real tests of their offspring’s capabilities. Not the least may be the founding entrepreneur’s own deep-seated resistance to the succession process itself, based on fears of surrendering control of the company and facing one’s own mortality. Entrepreneurs tend to be narcissistic personalities who do not find it easy to share the limelight with another, even a son or daughter. This is the theme of the classic biblical story of King Saul and his efforts to destroy David, the young warrior who enjoys such great popularity in the tribe that the king fears David may one day usurp his throne. For some of these same reasons, a founder may avoid making a choice of successor, stretching out the period of ambiguity and heating up the horse race between the candidates.

The process of transition to a Controlling Owner structure does not end with the selection of the new leader. There are several other tasks that must begin before the transition actually takes place, which continue after the new controlling owner is in place. One is to quickly put the successor into roles in the company that will showcase his or her strongest talents and provide an opportunity for quick results—ideally with good financial consequences for the company and any minority shareholders. Skepticism and resistance will begin to fade as soon as the new controlling owner can demonstrate that he or she can grow the business or produce handsome dividends in the future. There are other challenges as well. For example, the talents and performance of the single successor in a Controlling Owner to Controlling Owner transition will inevitably be compared with those of his or her predecessor. The parent must therefore pay special attention to ensuring that the successor’s career development builds self-confidence and provides measurable evidence of his or her leadership ability. This is not always easy for the retiring controlling owner, caught in the “King Saul” situation discussed earlier. It takes some sensitivity to honor the senior generation’s needs to have its contribution and continuing value validated, while making room for optimism that the new controlling owner will bring fresh opportunities and strengths.

The second task is the assessment of the tools, resources, and experiences that the new controlling owner will need in order to fulfill the leadership role, and providing for the development of the new leader. In a generational transition from one controlling owner to another, much of the mentoring of the successor is necessarily done by the incumbent. The process is thus intensely personal, and the quality of the relationship between parent and offspring becomes critical during the planning process. An in-depth study of successions at twenty family companies in 1988 concluded that companies in which the parent and the successor enjoyed some activity together outside the company were the most effective in carrying out the transfer of power. Whether it was tennis, or cooking, or orchard growing, the shared activity served to lessen the tensions between parent and child that inevitably arise during the planning process.13

The final task is the resolution of the family’s financial affairs, in line with the choice to transfer ownership control of the business to one individual. For businesses moving toward a Controlling Owner structure, one of the requirements is obviously to establish, in advance, provisions—and cash—for buyouts of dissident shareholders, should a conflict arise that threatens to paralyze the business.

The Transition to a Sibling Partnership

Parents who aspire to a Sibling Partnership in the next generation usually carry the value that family solidarity is just as important as unambiguous management authority. These business owners have a strong concept of what it means to be good parents as well as successful business owners. They wish to see their children working together closely and harmoniously, a band of brothers and sisters preserving family values and carrying the enterprise to new heights. Sometimes that vision is based on optimism about expanded future opportunities for the company and the family; other times it reflects an assessment of the world as a threatening place, in which family members must “circle the wagons” and look out for one another’s interests in the spirit of “one for all, all for one.”

The dream of a Sibling Partnership, like the single hero model that underlies the Controlling Owner dream, has a rich cultural history, from the ancient stories of Moses and Aaron or Damon and Pythias to the French Revolution, which glorified replacing patriarchal authority with fraternal leadership based on equality.14 The goal of interdependence requires the partners to subordinate their own ego needs and to truly appreciate and celebrate one another’s triumphs. The spirit of this collaboration can be summed up: “Your win is his win; his loss, your loss.”15

From a management point of view, multiple leadership offers opportunities for synergies from the combined talents and skills of a team, along with assurances of continuity should any one partner be disabled or die. A study of corporate CEOs by Richard Vancil shows that a number of large public companies such as General Motors now concentrate top management responsibility in an office of the chief executive, consisting of several executives.16 In an era when corporate America has discovered the value of teamwork at every level, and in a generational cohort with so many family businesses currently passing from first- to second-generation control, Sibling Partnerships have become an increasingly attractive option.

The toughest decision for parents who envision a Sibling Partnership in the future is: Are our offspring really capable of collaborating? In the most successful cases, parents make a realistic assessment of whether their children get along well and whether the distribution of skills and talents in the group is such that they will make an effective team. The parents start early to encourage the kind of sharing and collaboration that will be necessary for a sibling system to survive when the children begin working together as adults. However, the dream of a harmonious interdependence of siblings with complementary talents has irresistible appeal for some parents, which overwhelms such a clear-eyed assessment. In these cases, parents wish so profoundly to see this vision fulfilled that they ignore evidence of deep-seated rivalries among their children. Or, as discussed in chapter 1, they may try to fabricate a Sibling Partnership precisely to compensate for the disengaged style that has evolved in the family, and which they find disappointing. The decision to create a Sibling Partnership may, indeed, be a reactive choice, in which parents set the offspring up as equal partners precisely in order to prevent the acrimony that is likely to erupt if any one of them is given more power than the others.

Obviously, the choice of a partnership can be destructive to the business if it locks incompatible siblings into harness together, or prevents the most capable next-generation members from assuming leadership and having a decisive voice in business operations. The Sibling Partnership is a hard system to create and to maintain in practice. These partnerships are most likely to succeed when, as in the Lombardi family, the siblings are all capable and well trained, when the talents and special skills of those who work in the business are more or less complementary, and when a career in the company is seen as an option for those whose abilities and ambitions are a good fit with company needs, whereas others can choose not to join the business without loss of status in the family. The partners not only must be willing to subordinate their egos and share the limelight, they also must be extraordinarily flexible and willing to compromise when deadlocks arise over major issues. Finally, of course, they must have a strong commitment to making a consensus-based system work.

When these requirements are satisfied, the mutual knowledge of one another’s general attitudes and business philosophy, which come from years of growing up together and working within the family system, can unleash powerful synergies. Deutsch cites the example of a successful tennis doubles team: the partners are “promotively interdependent” because both play at comparable levels and yet each brings some skills—speed, a strong net game, an outstanding backhand—that raise the pair’s level of performance.17

The early stages of the transition to a Sibling Partnership raise in a greatly intensified form the dilemma between competition and collaboration that was introduced in the earlier discussion of selecting a Controlling Owner successor. Some families, in an effort to strengthen bonds between the potential partners, encourage activities in which the siblings can learn together and have time to exchange ideas, such as attending an executive training seminar at a university. The members of the sibling group in the business may be assigned to special projects that test and foster their ability to work as a team; for example, the group may be asked to collectively recruit, interview, and make recommendations on candidates to serve on the board of directors. In all these activities, the juniors are assessed not only on their individual work performance but also on their ability to work within the group and contribute to building consensus.

This is in contrast to the policies in other families, which are more concerned with creating data for the differential evaluation of siblings than they are with fostering a collaborative Sibling Partnership. These families will often create competitive conditions specifically designed to see which siblings rise to the top and take control, as the parentally sanctioned quasi-parent or first among equals. Although this tournament atmosphere does sometimes help the senior generation evaluate the candidates, there are significant costs. Once the junior generation realizes that the seniors want them to compete and their futures are on the line, they are often forced to become completely self-protective in relation to their siblings. Compromise, collaboration, and sharing credit are risky, self-defeating strategies, much to the detriment of the company and the developmental progress of the successors as a group. Also, the idea that truly objective data are created in such a “dog-eat-dog” atmosphere is usually a myth. Opportunities to shine are not really equally distributed. Finally, teamwork and collaboration may be critical skills for success in the next-generation Sibling Partnership, but they are not rewarded in this environment. This may lead to the wrong sibling being identified as the first among equals or even the quasi-parent, which usually results in a breakdown of the system once the parents are no longer around to enforce it.

There are ways that Sibling Partnerships can differentiate without going too far toward destructive competition. Sibling systems consisting of equal partners who are all capable and ambitious will sometimes make concessions to the need to act decisively. This may result in one sibling’s representing the business to associates, to bankers, and in the community, and another’s being the voice of leadership inside the company. In a multidivisional business, each partner may be in charge of a specific division or profit center. In a functional organization, the siblings may lead separate departments. In preparing for the transition from a Controlling Owner to a Sibling Partnership system, the senior generation must find the middle ground between establishing clear boundary lines, acknowledging each sibling’s autonomy in his or her own domain, and muting the competition between divisions or departments.

Even where rivalries do not exist, the siblings can become myopic in focusing on their own fiefdoms and lose sight of common objectives. Sometimes “respect for the other siblings’ territory” can become exaggerated into separationist procedures that are detrimental to the company as a whole. Although a division of labor based on the individual skills and interests of the partners is desirable, the group must also stay focused on common objectives. They must coordinate their efforts on certain key functions for the whole company, such as strategy, allocation of capital, and tax planning. Some workable balance must be found between individual expression and the collective interests of the whole organization. This is especially true as the sibling partners begin to reach the Working Together stages in their individual family development, and to prepare the next generation for leadership. In one large retail company in the southern United States, run profitably by two brothers for twenty years, neither brother’s children were permitted to work in the sectors of the business managed by their uncle. This was part of the policy to protect the discretion of each brother from intrusion by the other. As the brothers neared retirement, they realized too late that none of the otherwise-competent cousins was prepared to take over as general manager of the entire company.

The partners must make a pact to stick together and strongly resist any efforts by employees or outsiders to play one sibling off against another and divide the group—which frequently happens in sibling-led companies. Just as important, they must work out specific rules for resolving the arguments and breaking the impasses over major decisions that inevitably occur in any business organization. Some of the rules that we have seen attest to the flexibility and ingenuity of families in finding ways to prevent friction among people in close business relationships. One group of partners in Texas, for example, has developed a kind of lottery in which each gets a turn in having his viewpoint prevail when there is a deadlock. The brothers keep track of whose turn it is to prevail with an amulet that is worn around the neck at meetings and functions like “the Force” in Star Wars. Once the brother who is wearing it uses the amulet in order to have his view prevail on a major decision, he must pass it to the next brother, who also has the opportunity to use it just once. One reason this ritual seems to work is that it promotes consensus. The brother who wears the amulet wants to reserve “the Force” for a decision that he feels very strongly about, and thus is more willing to compromise with his siblings on issues of lesser importance to him. By the same token, the other brothers know that, when a conflict arises, they will lose out to the brother wearing the amulet—with whom they may vehemently disagree—unless they can reach a compromise.

We have seen in the case of the Lombardis that a partnership with a first among equals can work impressively. Although Paul Jr.’s authority sometimes appears to duplicate his father’s, his siblings constantly remind him that his powers are, in fact, far more circumscribed. At the same time, the Lombardis’ partnership functions effectively because each of the siblings not only acknowledges the skills and contributions of the others but also trusts the others to perform their roles and carry out their responsibilities capably. The Lombardis are highly competitive at times, but they understand that their rivalries trace back to childhood, and they are able to laugh and joke about them. Humor is one way that brothers and sisters can make a point in a nonthreatening way when a sibling’s behavior provokes or offends. A sense of humor about their rivalries may be one of the clearest signs that siblings will be able to manage their tensions in a partnership. The challenge to both seniors and juniors in similar companies is to correctly assess, first, whether such a critical balance and mutual appreciation of talents exists and, second, whether each of the partners has some insights into his or her limitations. Again, this is no easy task.

The Transition to a Cousin Consortium

As companies grow in size and families proliferate in later generations, it becomes more and more difficult to preserve the family influence. The dream of a Cousin Consortium company is a vision of a network or clan of cousins with a common lineage, ancestral symbols, stories, and traditions. The dream becomes the binding force for an extended group of families—like the Rockefellers in the United States, the Rothschilds in Europe, the Mogi family of the Kikkoman Company in Japan—that traces its roots to the founders of the company and their heroic accomplishments. The different family branches and the numerous cousins may not be as intimate as their sibling parents. Only a few of them may be active participants in the business. They may live far apart and come together only for occasional clan meetings. But they provide a far-flung support kinship network whose members can call on one another for help in time of trouble and even, in some cases, for financial assistance.

Cousin Consortiums tend to be associated with families that have enjoyed considerable success in business and accumulated substantial wealth. This is largely because, below a certain threshold of resources, an enterprise cannot continue to provide livelihoods for an expanding number of family members. Interest in the legacy of the business tends to wane as most cousins must seek alternative careers and sources of income. On the other hand, if several branches of a family and numerous cousins still feel strongly about the legacy and wish to retain some connection with the company, the challenges of governing in the next generation become far more complex for those who remain involved. Some family businesses in Europe and Latin America, which have existed for three or four generations, may include as many as 200 cousins who have some equity in the company. In addition, a large number of them may hope to make careers in top management.

In chapters 1 and 6, we have discussed the many dilemmas inherent in the complexity of these Cousin Consortiums. Of the many other challenges that confront Sibling Partnerships as they anticipate a transition to a Cousin Consortium, maintaining a balance of power among the various branches is unquestionably the most critical. One significant determinant of whether such a balance of power can be achieved is the simple numeric distribution of cousins among the various branches. In most extended families, the branches have unequal numbers of offspring, and that is where trouble begins.

Often each sibling partner will divide stock equally among his or her children, because that was how the founder did it when the company moved from a Controlling Owner structure to a Sibling Partnership. Thus the family chooses a Cousin Consortium structure by default, without realizing the full implications of the choice. For example, a successful leather products company in Spain is owned equally by four brothers. Each brother plans to divide his stock equally again and establish a Cousin Consortium in the next generation. This has been one of those well-functioning egalitarian Sibling Partnerships. For thirty years the brothers have been accustomed to having an equal voice in the company’s policies and decisions. In considering the ownership structure for the next generation, however, the brothers must wrestle with a different reality. The oldest brother has five children; two work in the company, and three do not. The second brother has only one son, who heads the marketing department. The third brother has four children, two working in the company and two not. And the youngest brother has five children, all of whom are still in school.

It is easy to see how these asymmetries in the next generation must be considered before beginning the transition to a Cousin Consortium. The second brother’s son stands to inherit fully one-fourth of the company’s stock, whereas his cousins will receive only a fraction of their father’s fourth. This has naturally increased the influence of the second brother’s son, who is already the odds-on favorite to be the next CEO. Fortunately, this “lead cousin” happens to be a very competent manager who has earned credibility among both family and nonfamily senior managers by quadrupling sales during his tenure as head of marketing. In addition, he has given other family members assurances that he will not abuse his advantageous ownership position. Nevertheless, his cousins privately worry that he might do so.

The fundamental dilemma in designing an ownership structure for the Cousin Consortium is whether to undertake a distribution of stock per stirpes, maintaining the quality of branch ownership, or to reallocate shares so that each of the cousins controls an equal amount of stock, maintaining the equality of individual ownership. This is a perfect example of how the world changes between the Sibling Partnership and Cousin Consortium stages. For the siblings, branch and individual equality were the same thing; for the cousins, unless each sibling has exactly the same number of heirs, they are mutually exclusive. Each option poses significant challenges. The resolution of this dilemma is so tricky that, more often than not, the sibling partners take the easy way out—they do not discuss it at all. As a result, everyone anticipates that a per stirpes distribution will take place, and the politics of the succession process occur with one eye on the new ownership power balance that will result in the cousin generation.

Although siblings are often very active in protecting the interests of their own children (as discussed in chapter 6), at the same time they usually do everything they can to avoid arguments over which of their children are most deserving and best qualified for leadership positions in the next generation. Evaluating one another’s children is probably one of the most sensitive—and potentially explosive—challenges of sibling partners planning a succession. The problem is compounded when many capable cousins are competing for a few top management spots in the company and leadership positions in the ownership group, particularly on the board of directors. Sibling partners sometimes respond with structural gerrymandering that diminishes the need to make hard comparative assessments of the cousin candidates. Cousins may be dispersed to widely separated functions where they do not interact and where comparing their performance is an “apples and oranges” situation. We have described a case in which each offspring could only work in his or her father’s division; in contrast, sometimes offspring are allowed to work anywhere but in their parent’s domain. A growing number of families go to the extreme to avoid what they consider the inevitable destructive conflict that follows competition: they ban the cousin generation from management roles altogether. All of these solutions may satisfy some family needs, but they almost certainly interfere with the best course of management development for the cousin generation.

Furthermore, this kind of uncoordinated preparation threatens the company’s ability to continue as one enterprise. Keeping the cousins apart is no way to build a foundation for a strong, collaborative Cousin Consortium. The solution is not to avoid comparisons at all costs (which responds to the siblings’ discomfort more than to the cousins’), but to structure the management development process so that the best solutions for the company and the overall family can be rationally discovered. This requires the seniors to set up forums in which ownership and governance issues are confronted and procedures are worked out to appraise, select, and train successors as evenhandedly as possible. To enhance the fairness of the selection process, many family companies set up assessment committees, which include family members who are known for fairmindedness or who have no offspring involved, outside directors, and trusted senior managers (described in more detail in chapter 8). In fact, some companies, like a large Sibling Partnership in northern Mexico, turn the process over to a committee made up entirely of nonfamily board members and staffed by the senior human resource manager and the nonfamily heads of the operating divisions. In the right situation, where the nonfamily manager has considerable credibility and the family sticks by its noninterference policy, this can be a very rational and successful approach.

The options open to such committees will depend on the parameters determined by the family (ideally in a family council, as will also be discussed in chapter 8) on the desired relationship between the family and the company in the Cousin Consortium. If the family has decided that the protected role of the family members will be only in ownership (that is, through the board), then the committee may be instructed to evaluate the family management candidates in open comparison with the nonfamily talent that the business can recruit. A modified version would reserve the CEO position for a family member, but enforce no special consideration for cousins for other management positions. On the other hand, the family may want to encourage competent family participation throughout the top business management. In that case, the committee must be guided by these family goals—even if there is a cost in objectively assessing the professional abilities of the cousin participants. By custom in Japan’s Kikkoman Company, for example, each of the eight branches of the owning family is allowed to designate one and only one family member in each generation to participate in the company (although a parent and one offspring, from different generations, may work in the business at the same time).

Finally, perhaps the biggest challenge for Cousin Consortiums is to keep the dream alive. With each succeeding generation, the family’s influence tends to wane, and, unless the ownership tree is severely pruned, the stock will become increasingly fractionated. Cousins who want to use their wealth to pursue other careers and interests may seek to sell their shares, which makes some sort of buyout process and fund essential at this stage. Rather than too many family members knocking at the door seeking management positions, there may be too few—or none at all. The family may be held together by nothing more than their common financial interest, and if the returns on their investment are not better than what they could earn elsewhere, some stockholders may seek opportunities to sell their shares in the family company.

The gradual professionalization of management may contribute to the weakening of the family’s identification with the company. The Dorrances of the Campbell Soup Company are examples of third-generation family members who have had difficulty maintaining the family legacy in the company. Although they still control a majority of Campbell’s stock, they have never participated in management, and a few of the cousins have talked about selling their stock.18 By contrast, the traditions of the Ford family remain strong at Ford Motor Company through a few heirs of the founder in every generation who have served in management and board positions.

If the family determines that it wants to keep alive the dream of the family business, then it has to recommit in each generation to put in the required effort. For many companies at the Cousin Consortium stage, this is reflected in periodic clan meetings or retreats at which the elders may tell stories that illuminate the family’s values and traditions. For example, the seniors in one Canadian enterprise that has 200 cousins in the fifth generation talk at such events of the family’s dogged efforts to succeed—captured in its motto, “Persistence Pays.” The retreats feature ritual retelling of core myths about the family and the business: how the founders tried many beer recipes before hitting on one that became a best-seller, and how the family decided to tough out a provincewide labor crisis when other beer makers sold their plants or moved away because of the threat of violence and sabotage. These heroic stories inspire younger family members to carry on the legacy.

The company must also develop a range of opportunities for contributions by those young family members who do not want or are not offered jobs in top management. Participation on company boards of directors, family councils, boards of family foundations—all afford young people opportunities to get experience and remain connected with the family legacy even though they may not be involved in management.

The process of succession is the vehicle that moves the family along from stage to stage on the ownership and family dimensions. It is part voluntary and part irresistible; part planned and part developmental. The core perspective of our model is that succession goes far beyond unplugging the retiring leader and plugging in the new one. Succession is a transitional process along all three dimensions. It involves uncovering and examining the dreams of all the key players for the future, and forming from them a coherent dream for the family business. Then it involves understanding the requirements of whatever future is chosen and doing the necessary work to prepare the system to succeed in that future. The fascination with the succession process in family business is very understandable; it is complex and compelling. Helping it along requires an application of developmental principles of ownership, the family, and the company—a formidable challenge, but one with extraordinary rewards.

NOTES

Levinson 1971; Danco 1975; Barnes and Hershon 1976. Handler (1994) has prepared an excellent summary of this literature.

Lansberg, forthcoming.

The central arguments in the fascinating issue of ownership versus management power in American corporations are outlined in Berle and Means’s classic book (1932) and in the counter arguments that have followed (Larner 1966; Levine 1972; Zeitlin 1975; Francis 1980).

Daily and Dollinger 1992.

Lansberg, forthcoming.

Levinson 1978, 91.

Dumas 1990.

Menchik 1980; Swartz 1996.

Danco 1975.

Barnes 1988, 10.

Johnson 1988, 10.

As the data gathering proceeds, in some cases the senior generation may benefit from reopening the question of whether the Controlling Owner form is really workable for the next generation. The parents may believe in one-person governance philosophically, but there may not be one sibling who demonstrates clear superiority over the others as the selection process unfolds. Estate planning advisers may make it clear that, no matter how carefully things are structured, there will be an unacceptably unequal division of assets if one heir is given controlling interest in the company. Or the sibling or cousin group may themselves convey that they would feel more comfortable in a Sibling Partnership or Cousin Consortium, perhaps with a “first among equals.” Parents are well advised to stay open to modifying their dream if circumstances warrant—provided the more collaborative goal is not just wishful thinking, and the siblings have demonstrated that they can get along and work together.

Lansberg 1985.

Hunt 1992.

For more on this idea, see Deutsch’s discussion of “promotive interdependence” in the resolution of conflict (Deutsch 1977).

Vancil 1987.

Deutsch 1977, and personal communication.

Muson 1995.