Introduction

A Developmental Model of Family Business

WAL-MART. CARGILL. McGraw-Hill. As well as Petralli and Sons Auto Repair, Ethel’s Tree Service, and Goldman Furniture Co. This book is about families who own or manage businesses and about the businesses themselves—from the corner convenience store with a handful of employees to the multinational conglomerate with fifty thousand. They include some of the best-known companies in the United States, as well as the thousands of unknowns. The variety is enormous, but all these varied companies share one core characteristic: they are connected to a family, and that connection is what makes them a special kind of business.

Some of those companies proudly identify themselves as family businesses, like the third-generation furniture store with brothers and sisters and cousins in all of the management roles. Others are controlled by families but do not think of themselves primarily as family businesses, but rather as “private” companies, manufacturers, real estate brokers, or members of the construction industry. Either way, the people involved feel the difference. Family business owners are well aware of how different their role is from that played by shareholders in companies owned by many public investors. Employees in family businesses know the difference that family control makes in their work lives, the company culture, and their careers. Marketers appreciate the advantage that the image of a family business presents to customers. And families know that being in business together is a powerful part of their lives.

Who Are the Family Firms?

Family businesses are the predominant form of enterprise around the world. They are so much a part of our economic and social landscape that we completely take them for granted. In capitalist economies, most firms start with the ideas, commitment, and investment of entrepreneurial individuals and their relatives. Married couples pool their savings and run a store together. Brothers and sisters learn their parents’ business as children, hanging around behind the counters or outside the loading dock after school. It is not just an American dream to make a business venture succeed and then to add “and Sons” (and recently “and Daughters”) to the sign over the front door. The success and continuity of family businesses are the economic Emerald City for a large portion of the world’s population.

Articles on family business make various guesses about the number of family-controlled companies, but even the most conservative estimates put the proportion of all worldwide business enterprises that are owned or managed by families between 65 and 80 percent.1 It is true that many of these companies are small sole proprietorships, which will never grow or be passed down from generation to generation. But it is also true that many of them are among the largest and most successful businesses in the world. It is estimated that 40 percent of the Fortune 500 are family owned or controlled.2 Family businesses generate half of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and employ half the workforce. In Europe, family firms dominate the small and medium-sized firms and are the majority of larger firms in some countries.3 In Asia, the form of family control varies across nations and cultures, but family firms hold dominant positions in all of the most developed economies except China.4 In Latin America, grupos built and controlled by families are the primary form of private ownership in most industrial sectors.5

If family businesses are so common, how can they also be special? When Freud was asked what he considered to be the secret of a full life, he gave a three-word answer: “Lieben und arbeiten [to love and to work].” For most people, the two most important things in their lives are their families and their work. It is easy to understand the compelling power of organizations that combine both. Being in a family firm affects all the participants. The role of chairman of the board is different when the company was founded by your father and when your mother and siblings sit around the table at board meetings, just as they sat around the dinner table. The job of a CEO is different when the vice president in the next office is also a younger sister. The role of partner is different when the other partner is a spouse or a child. The role of sales representative is different when you cover the same territory that your parent did twenty-five years earlier, and your grandparent twenty-five years before that. Even walking through the door on your first day of work on an assembly line or in a billing office is different if the name over that door is your own.

This sense of difference is not just a feeling. It is rooted in the reality of the business. Companies owned and managed by families are a special organizational form whose “specialness” has both positive and negative consequences. Family businesses draw special strength from the shared history, identity, and common language of families. When key managers are relatives, their traditions, values, and priorities spring from a common source. Verbal and nonverbal communication can be greatly speeded up in families. Owner-managers can decide to solve a problem “like we did it with Uncle Harry.” Spouses and siblings are more likely to understand each other’s spoken preferences and hidden strengths and weaknesses. Most important, commitment, even to the point of self-sacrifice, can be asked for in the name of the general family welfare.

However, this same intimacy can also work against the professionalism of executive behavior. Lifelong histories and family dynamics can intrude in business relationships. Authority may be harder to exercise with relatives. Roles in the family and in the business can become confused. Business pressures can overload and burn out family relationships. When they are working poorly, families can create levels of tension, anger, confusion, and despair that can destroy good businesses and healthy families amazingly quickly. The public is well aware of family tragedies that can accompany business disasters. The Bingham family in Louisville, the Pulitzers, and the du Ponts make for compelling reading. For many years “Dallas” and “Dynasty” were the two most popular television programs in the world, portraying an America of wealthy business families tearing themselves apart.

It is unfortunate that the sensational failures sometimes overshadow the beauty of successful family enterprise. When they are working well, families can bring a level of commitment, long-range investment, rapid action, and love for the company that nonfamily businesses yearn for but seldom achieve. Lieben and arbeiten together are a powerful foundation for a satisfying life. Family businesses are tremendously complicated, and at the same time these firms are critical to the health of our economy and to the life satisfaction of millions of people.

However, professionals are not always prepared to deal with the special nature of family companies. The influence of families on the businesses they own and manage is often invisible to management theorists and business schools. The core topics of management education—organizational behavior, strategy, finance, marketing, production, and accounting—are taught without differentiating between family and nonfamily businesses. The economic models underlying most management science depend on interchangeability of decision makers, so that it does not make any difference “who” anybody is. Business newspapers and magazines usually treat family involvement in a firm as anecdotal information—colorful and interesting, but rarely important.

This book presents a model for understanding this extraordinary form of business. It is designed to help professionals from all disciplines—business consultants, lawyers, accountants, family counselors, psychologists, and other advisers—to work with the enormous complexity of these systems. It is also intended to help family business owners think more clearly about themselves.

Conceptual Models of Family Firms

The study of family business is still relatively new. The scholarly work began with consultants’ case descriptions of family firms. In the last few decades, researchers from management and organizational sciences have begun to apply their models, from organizational behavior, strategy, human resource management, and finance, to smaller-sized or privately owned companies. At the same time, family therapists have begun to apply concepts such as differentiation, enmeshment/disengagement, and triangles to the subgroup of families who have businesses. The contributions of these scholars and practitioners, as well as the work of psychologists, sociologists, economists, lawyers, accountants, historians, and others, have begun to coalesce into conceptual models of family business.

Family Businesses as Systems

The study of family businesses as systems began with a few standalone articles in the 1960s and 1970s.6 These early classics focused on typical problems that appeared to hinder family firms, such as nepotism, generational and sibling rivalry, and unprofessional management. The underlying conceptual model held that family businesses are actually made up of two overlapping subsystems: the family and the business.7 Each of these two “circles” has its own norms, membership rules, value structures, and organizational structures. Problems arise because the same individuals have to fulfill obligations in both circles; for example, as parents and as professional managers. In addition, the business itself has to operate according to sound business practices and principles, while at the same time meeting family needs for employment, identity, and income. From the beginning, it was clear that finding strategies that satisfy both subsystems is the key challenge facing all family enterprise.8

This two-system concept is still very much in evidence today. Researchers and scholars use it as a basis for their analyses of complex organizational behavior, strategy, competitiveness, and family dynamics. Consultants and other practitioners find it useful in clarifying the sources of individuals’ behavior and decisions. For example, an estate planning attorney may be puzzled by a client’s reluctance to implement the most rational distribution plan, until she considers the client’s conflict between his desires as a parent (to treat each offspring equally) and as a business owner (to consolidate control in one successor). Similarly, an apparently illogical expansion strategy for a growing company may make sense only when one understands the needs of coowner siblings to keep their divisions equal size, no matter what. The conflicting pressure that the family and business circles put on individuals in the middle was the first practical concept in this field of study.

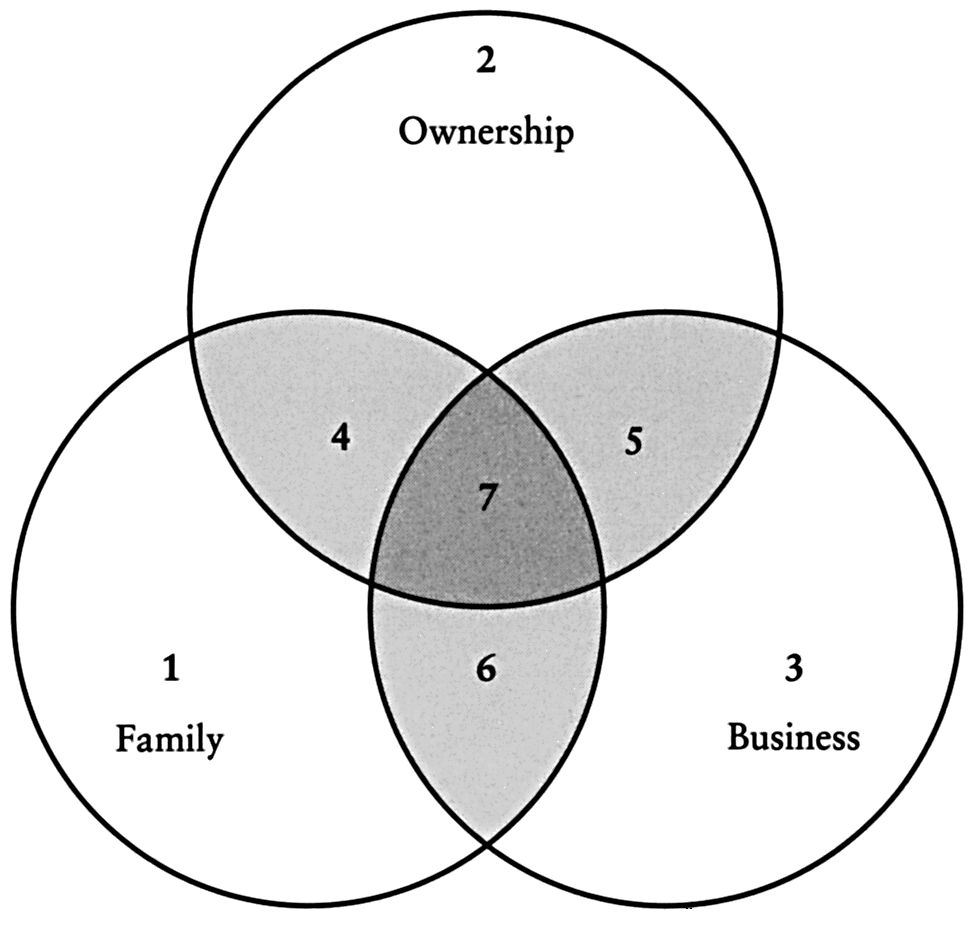

Tagiuri and Davis elaborated the two-system model with their work at Harvard in the early 1980s.9 They argued that a more accurate portrayal of the full range of family firms would need to make a critical distinction between the ownership and management subsystems within the business circle. That is, some individuals are owners but not involved in the operation of the business; others are managers but do not control shares. Our work with many different sizes of companies has supported their argument that many of the most important dilemmas faced by family businesses—for example, the dynamics of complex, cousin-controlled family businesses—have more to do with the distinction between owners and managers than between the family and the business as a whole. As a result, the three-circle model (figure I-1) emerged.

The three-circle model describes the family business system as three independent but overlapping subsystems: business, ownership, and family. Any individual in a family business can be placed in one of the seven sectors that are formed by the overlapping circles of the subsystems. For example, all owners (partners or shareholders), and only owners, will be somewhere within the top circle. Similarly, all family members are somewhere in the bottom left circle and all employees, in the bottom right. A person who has only one connection to the firm will be in one of the outside sectors—1, 2, or 3. For example, a shareholder who is not a family member and not an employee belongs in sector 2.—inside the ownership circle, but outside the others. A family member who is neither an owner nor an employee will be in sector 1.

Figure I-1 ■ The Three-Circle Model of Family Business

Individuals who have more than one connection to the business will be in one of the overlapping sectors, which fall in two or three of the circles at the same time. An owner who is also a family member but not an employee will be in sector 4, which is inside both the ownership and family circles. An owner who works in the company but is not a family member will be in sector 5. Finally, an owner who is also a family member and an employee would be in the center sector, 7, which is inside all three circles. Every individual who is a member of the family business system has one location, and only one location, in this model.

The reason that the three-circle model has met with such widespread acceptance is that it is both theoretically elegant and immediately applicable. It is a very useful tool for understanding the source of interpersonal conflicts, role dilemmas, priorities, and boundaries in family firms. Specifying different roles and subsystems helps to break down the complex interactions within a family business and makes it easier to see what is actually happening, and why. For example, family struggles over dividend policy or succession planning become understandable in a new way if each participant’s position in the three-circle model is taken into account. An individual in sector 4 (a family member/owner/nonemployee) may want to increase dividends, feeling that it is a legitimate reward of family membership and a reasonable return on investment as an owner. On the other hand, a person in sector 6 (a family member/employee/nonowner) may want to suspend dividends in order to reinvest in expansion, which might create better career advancement opportunities. These two individuals may also be siblings—similar in personality and style, and with a close emotional bond—who do not understand why they cannot agree on this question. Another common example concerns the difficult decisions a family must make about offering jobs to family members. Which children should be employed in the business? How much should they be paid? Will they be promoted? Viewed through the three-circle lens, different individuals’ opinions on questions like these become more understandable. A person in sector 1 (family circle only) might feel, “Give them all a chance. They’re all our children.” Sector 3 (business circle only), on the other hand, could say, “We only hire relatives if they are better than all other candidates, and their career movement is determined strictly by performance.” The three-circle model helps everyone see how organizational role can color a person’s point of view; personality conflicts are not the only explanation.

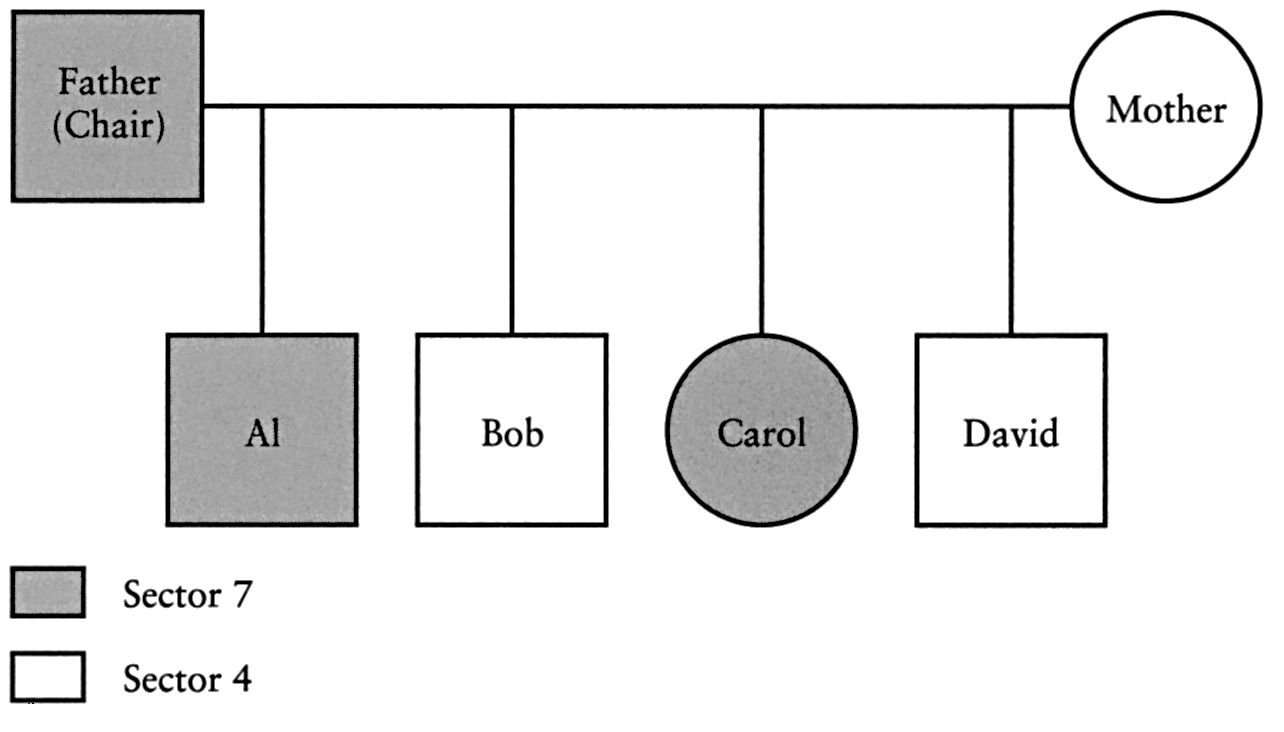

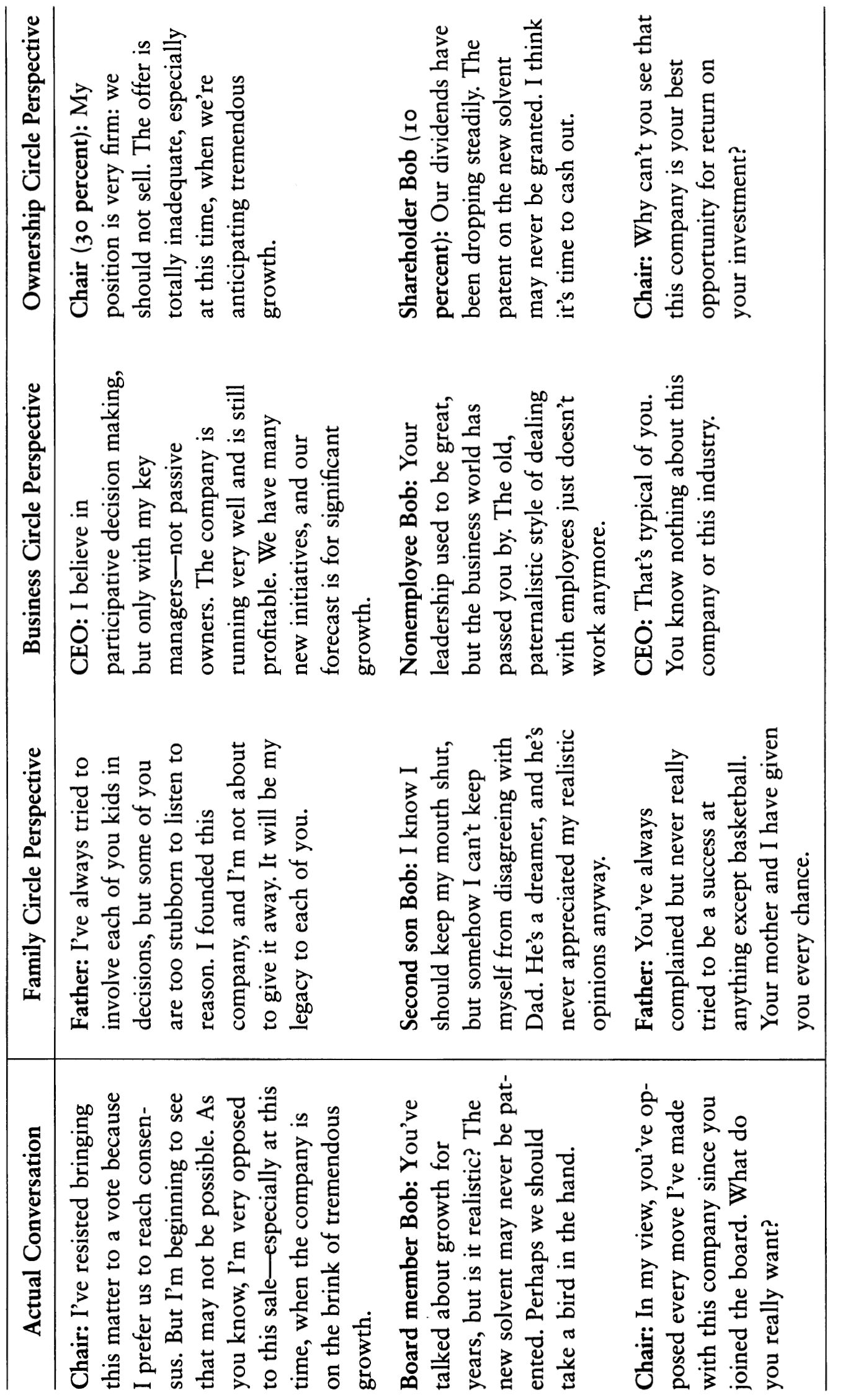

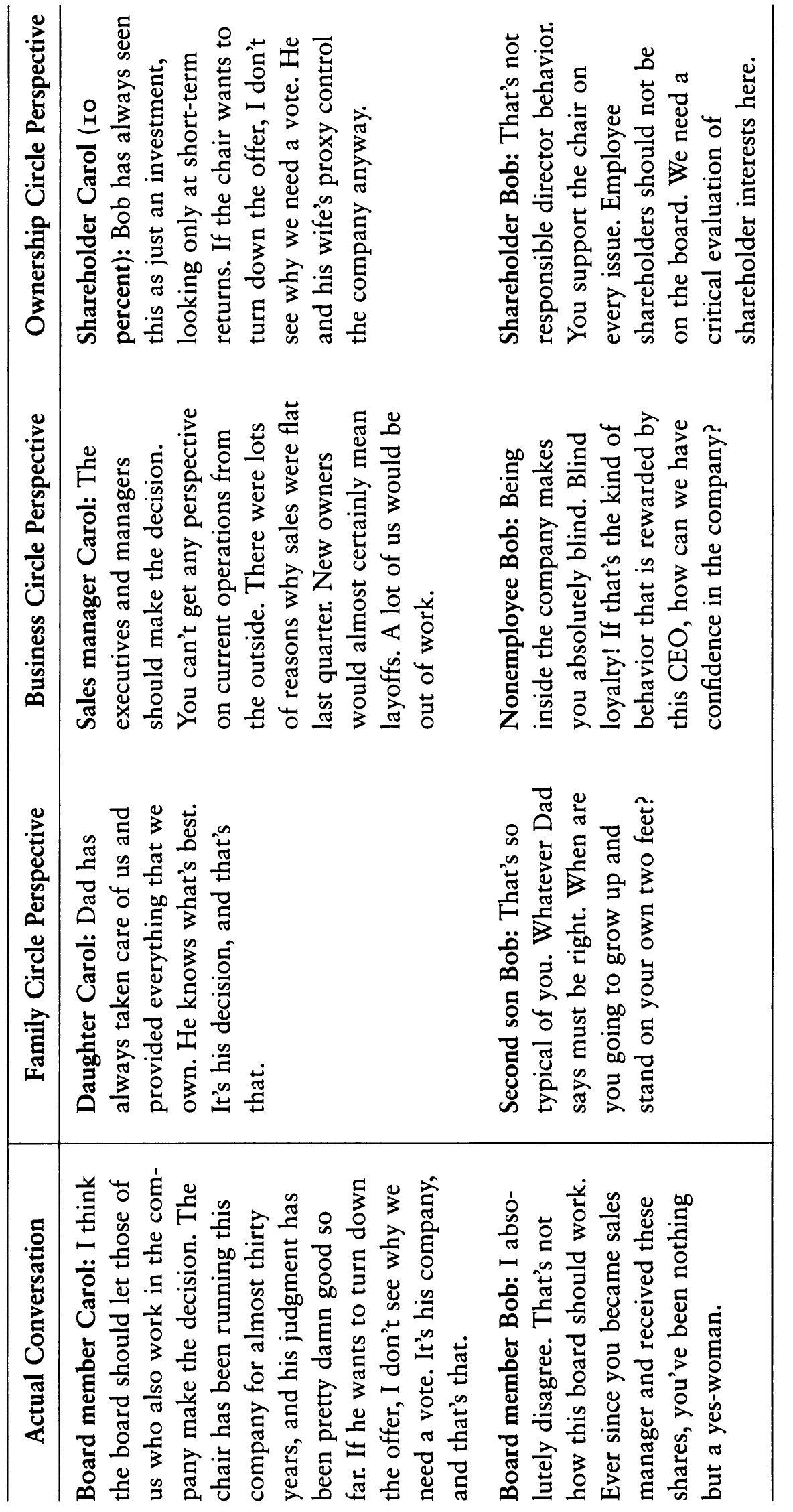

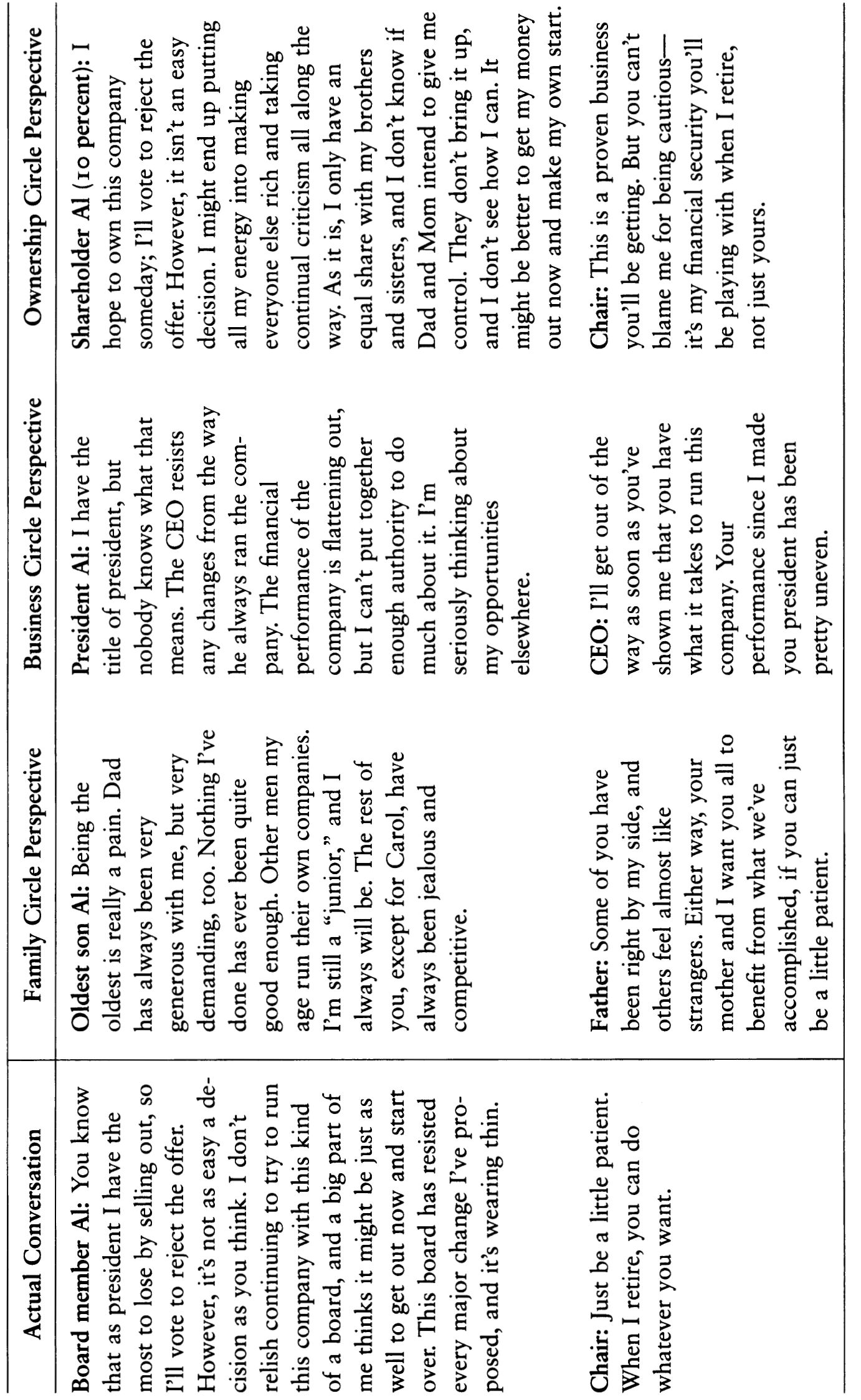

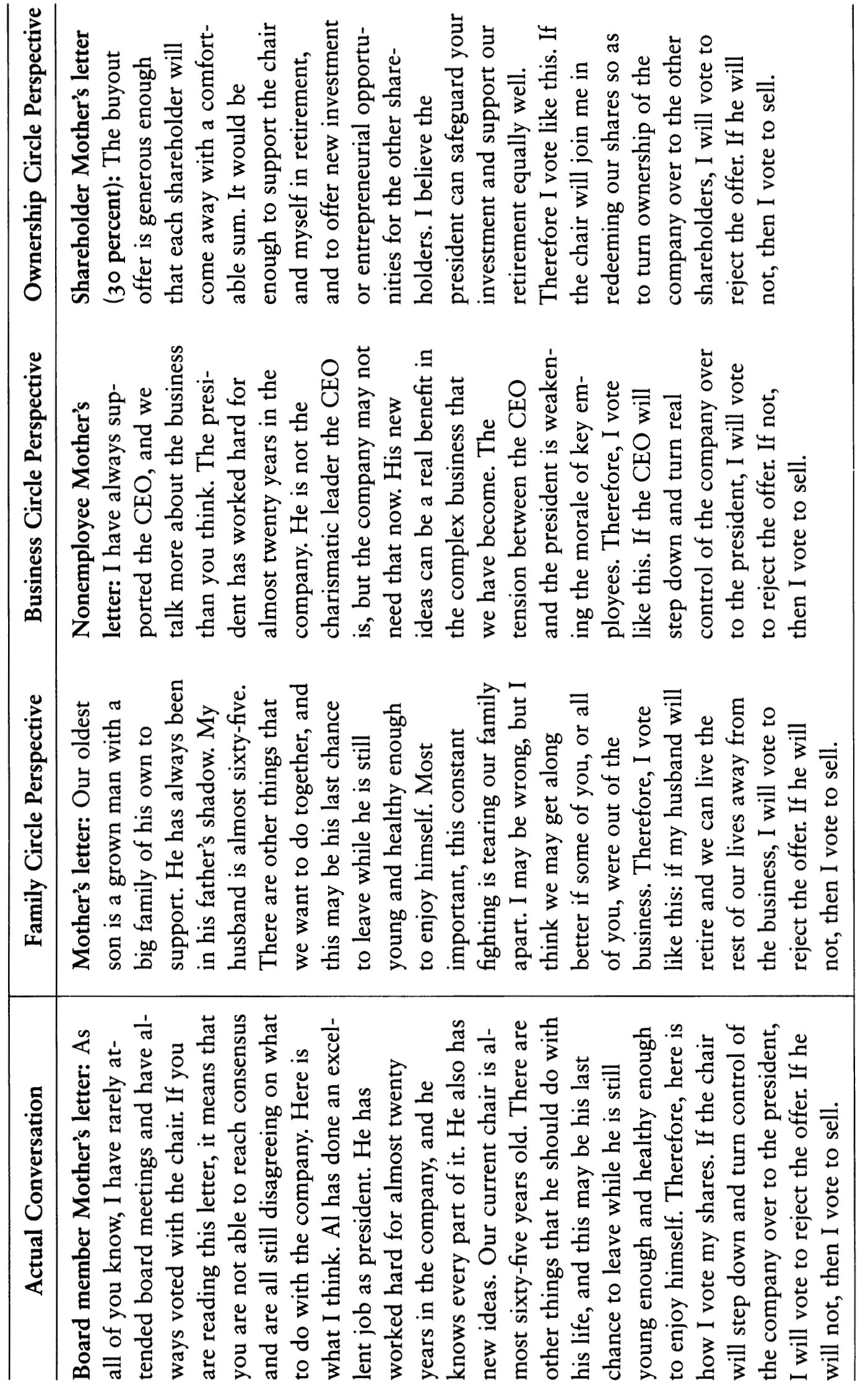

A further example can illustrate how messages from all three circles can be exchanged at the same time. The board of directors of Tru-Color, Inc., a family-owned paint manufacturer, is trying to decide how to respond to a buyout offer from a large competitor. The board is made up of six members of the Franklin family (figure I-2).10 Mr. Franklin, Al, and Carol work in the company. Because they are simultaneously family members, employees, and owners, they are in sector 7 of the three-circle model. Mrs. Franklin, Bob, and David do not work in the firm. As family owners, they are in sector 4. David has never participated in the board and has given his proxy to his mother. As the board debates the offer, each person’s statements reflect his or her role in all three circles: the family, the business, and the ownership group. In table I-1, on page 9, excerpts from their conversation appear in the left-hand column. Columns 2, 3, and 4 present the “between the lines” points that each individual is trying to make, reflecting his or her three different roles.

Figure I-2 ■ The Franklin Family

Mr. Franklin is convinced that he is serving all his roles—chair, CEO, and father—by keeping the company. As a father, Mr. Franklin is most concerned with his responsibility to take care of his family financially. He describes the company as his “legacy” for his children. As CEO, he wants to protect his authority to run the company as he sees fit, and as chair of the board, he insists that shares in Tru-Color are still a wise investment. His most vocal challenger is his second son, Bob, who views the same decision from the point of view of a younger sibling, nonemployee, and minority investor. Bob is acting as a son who has always had a difficult relationship with his father, as a critical observer of the CEO’s management style, and as a worried investor. The two men may be in conflict on many things, but their disagreement on this issue appears more rational and less arbitrary in light of their very different roles in each circle.

As the meeting progresses, other board members join the debate (see table I-2, page 10). Siblings may have grown up in the same family, but they also represent different combinations of roles. In the conversation captured in table I-2, Carol is not only guided by her personality and individual style, she is also in the role of youngest child, only daughter, recently promoted employee, key manager, and new shareholder. It is easy to understand why she finds herself in conflict with her older, nonemployed brother.a

Table I-1 ■ Tru-Color, Inc.:Bob’s Opinions

Table I-2 ■ Tru-Color, Inc Carol’s Opinions

Later in the meeting, the oldest son, Al, who has been quiet until now, is asked for his point of view (see table I-3, page 12). Everyone assumes that he will give a ringing endorsement for keeping the company in the family. The dynamics between generations are always complicated, especially between the current and designated leaders. Each of them is responding to the anticipated transfer of leadership in each of the three circles. Both Mr. Franklin and Al express the ambivalence he feels about “letting go” and “taking over.” The three-circle model helps us keep in mind that, not one, but three separate transitions are taking place, and they may occur at different times and involve different participants.

At the end of the board meeting, Mr. Franklin confidently announces that, even with Bob in opposition, the majority of shareholders clearly favor keeping the company. At that moment, Carol announces that she has a letter from Mrs. Franklin concerning the voting of her shares and those of the absent sibling, David. She has instructions to read it if the board was not unanimous (see table I-4, page 13).

The members of the Tru-Color family illustrate the complexity of family businesses that gives them such a special character. The major players are responding to more than one powerful agenda at a time. Each participant sees all the others as parents or children, coworkers, and coinvestors simultaneously. Messages often become confused when they originate in ambivalence. Even the individuals themselves do not understand what they are feeling, or where the tension and conflict originate. All of these dynamics complicate the tasks of any of the circles—family, business, or ownership.

The goals of theory, research, and intervention all converge on discovering frameworks to untangle the knots of such complex behavior. The three-circle model has been a powerful tool toward reaching that goal. By separating the domains, it clarifies the motivation and perspectives of individuals at various locations in the overall system. But an additional dimension is needed to bring this framework to life, and to make it more applicable to the reality of family and business organizations. That dimension is time.

Table I-3 ■ Tru-Color,: Inc Al’s Opinions

Table I-4 ■ Tru-Color,: Mother’s Opinions

Time and the Inevitability of Change

Psychological research is valuable in expanding our knowledge, but for most people, what we understand about human behavior comes from our personal experiences, often remembered in the form of stories. Consider the following four stories about family businesses:

Mr. A Jr. feels trapped in unending squabbles with his father. Mr. A Sr. founded the company twenty years ago, and just passed the role of CEO to Mr. A Jr. last summer. Managing his father’s continuing interference is only one of Mr. A Jr.’s problems. Profits are flat, and there is a need for significant new product development, which was a low priority in his father’s last years in the company. Mr. A Jr.’s wife feels that he has been working much too hard since taking over as CEO. He is so busy that he has almost no time for their daughter, and she is not sure about having more children soon if he will not be able to be more helpful.

Mr. B does not know how to respond to his brother Jim’s request that he employ Jim’s daughter in the company. Jim is one of the family shareholders and owns 25 percent of the company. Mr. B’s own daughter joined the accounting department last year after graduating from college, and his son is trying to decide whether to join the company or take a job with somebody else. Two of the company’s key nonfamily managers have expressed serious concern about too many family members in the business.

Mr. C’s daughter, the company’s vice president for marketing, wants to take the company in a new strategic direction. His son, who is the operations manager in the manufacturing plant, is opposed to any major changes. The board of directors and senior managers are split on the issue. Mr. C believes that some of the conflict is fueled by increasing competition between his children for the inside track as his successor. Both offspring have been with the company for ten years.

Mr. D and his wife intended to retire in three years, when Mr. D turns sixty-five, but now he is having second thoughts. He believes that his forty-year-old daughter, whom he named president two years ago, can successfully run the company, but he is not sure she comprehends how hard it will be. There is also troublesome conflict between his grandson, who works in the sales department, and his nephew, who is the new sales manager. In addition, a large corporation has recently approached Mr. D with a good offer to buy the company.

What do these stories have in common? They portray four typical dilemmas experienced by owner-managers in family businesses. They all illustrate examples of the complexity of managing differing norms, values, and expectations from various positions in the three circles. But, most surprisingly, they are all drawn from the same family business, at different points in time. Mr. A is Ben Smith at thirty, Mr. B is the same man at forty-five, Mr. C is Ben at fifty-five, and Mr. D is Ben at sixty-three.

To be alive is to be constantly changing. The A, B, C, and D stories about Ben Smith may all be about the same person in the sense that they are all about one human life, but in another sense Mr. Smith is never the same, from week to week or from year to year. Each experience and decision affects all those that follow. The course of any person’s unique development is the product of both the individual’s own maturation and his or her experiences in the world.

Systems and organizations also age and change. The family made up of a young couple and their six-month-old baby is not the same as the family with teenagers, or the family with elderly grandparents, adult offspring, and a new generation starting school. Similarly, entrepreneurial startups are not the same as businesses that have secured a place in the market but are concerned about growing. And both of these are different from older businesses, losing their edge and trying to generate the new ventures that will keep them competitive in the future. Because of the critical roles played by key individuals over long time spans, family businesses are especially affected by the inevitable aging of people in each of the sectors. The most important lesson we have learned in the past fifteen years of work with family companies is that our models must take time and change into account if they are to reflect the real world accurately.

Building a Developmental Model

The business, ownership, and family circles can create a snapshot of any family business system at a particular time. This can be a very valuable first step in understanding the firm. However, many of the most important dilemmas that family businesses encounter are caused by the passage of time. They involve changes in the organization, in the family, and in the distribution of ownership. For example, in the Tru-Color case, how different would the entire meeting have been a few years earlier, before the minority shares had been distributed to the four children? How different will it be a few years later, when Mr. Franklin has retired from the CEO position, and the balance of ownership has shifted to the younger generation?

It is easy to see how each of the circles changes when people enter and leave it over time. Families are an endless series of entries through marriage and birth, and departures through divorce and death. All of us have an intuitive understanding, based on our experience in our own families, that each of these additions and subtractions changes the family in some fundamental way. It is the same with businesses, as key managers come and go, and with shareholder groups, as new owners take on the responsibility of ownership and old ones relinquish it.

It is also important to see how the whole family business changes as individuals move across boundaries inside the system. In other words, a person’s movement from one sector to another, such as from “family member” to “family member/employee,” or from “employee” to “employee /owner,” can also stimulate a general reaction in the entire system. The full-time employment of the first member of a new generation in the business—as that individual crosses the boundary from family member only to family member/employee—is an important marker event. The first time that ownership shares are passed to new individuals, family members or nonfamily, is also a critical moment. Many of these transitions may be invisible—embedded in a tax-minimizing estate plan or an annual gift—but nevertheless have far-reaching consequences. So does the retirement of a senior family member executive, or the cashing out of shares by a family member or branch. The system’s adjustments to these boundary-crossing journeys of its members, and the meaning of those journeys in the lives of the individuals, are at the core of the entire family business phenomenon.

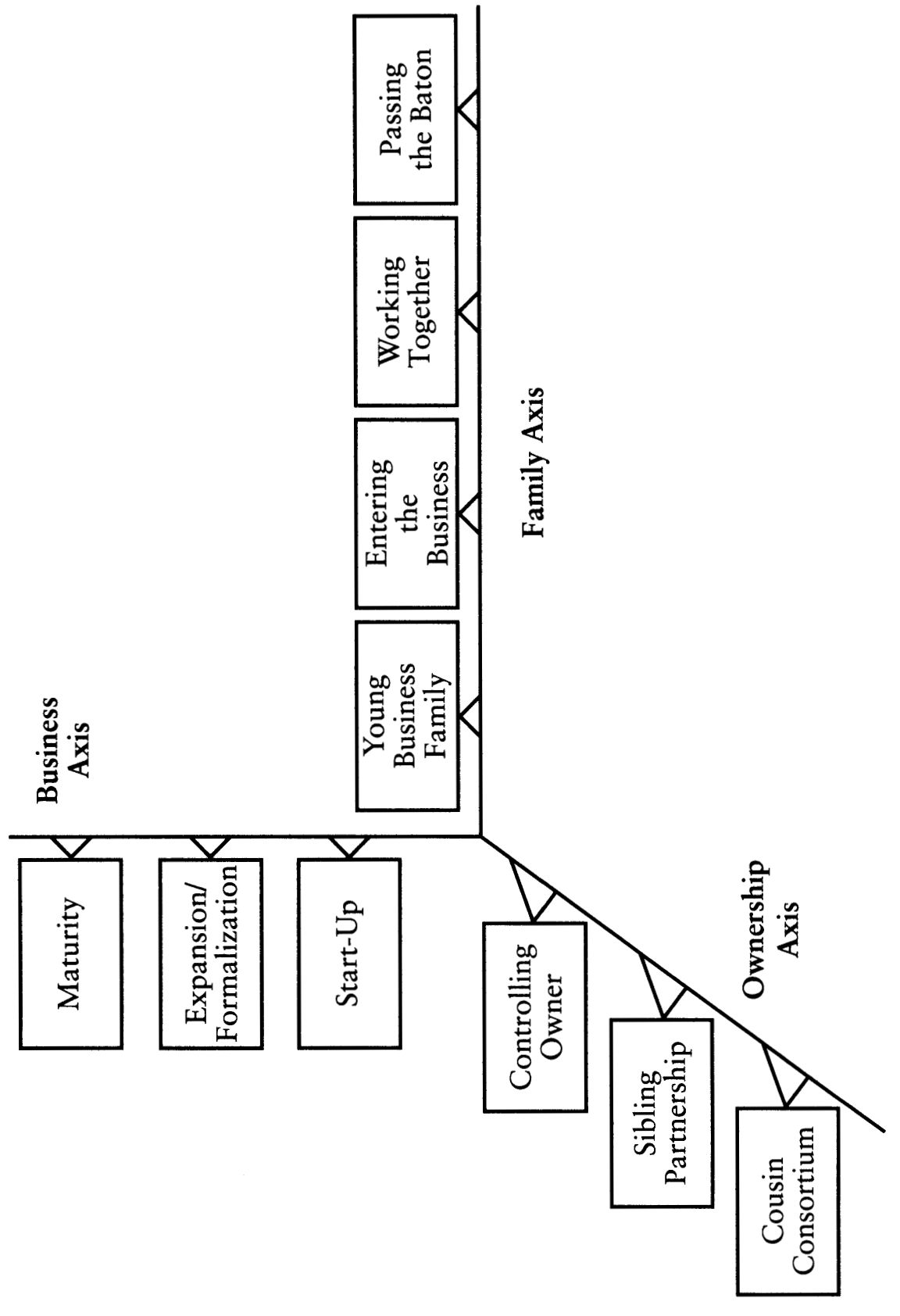

The result of adding development over time to the three circles is a three-dimensional developmental model of family business (see figure I-3). For each of the three subsystems—ownership, family, and business—there is a separate developmental dimension. The ownership subsystem goes through its sequence of stages, the family subsystem has its own sequence, and the business also progresses through a sequence of stages. These developmental progressions influence each other, but they are also independent. Each part changes at its own pace and according to its own sequence.

Figure I-3 ■ The Three-Dimnesional Developmental Model

Taken together as three axes of ownership, family, and business development, the model depicts a three-dimensional space. Every family business has progressed to some point on the ownership developmental axis, some point on the family developmental axis, and some point on the business developmental axis. The enterprise takes on a particular character defined by these three developmental points. As the family business moves to a new stage on any of the dimensions, it takes on a new shape, with new characteristics. We will discuss the way the three dimensions work together after first presenting each dimension in more detail.

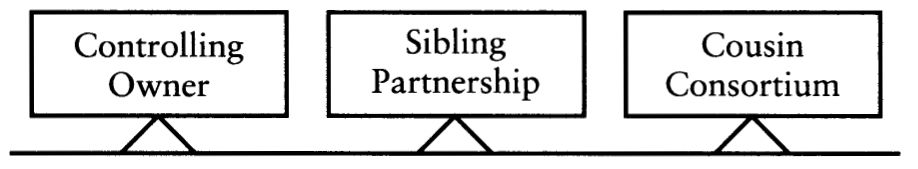

The Ownership Developmental Dimension

The first dimension describes the development of ownership over time (figure I-4). Our description of this dimension draws heavily on the work of John Ward.11 It recognizes that the different forms of family ownership result in fundamental differences in every aspect of the family business. There is, of course, an almost-limitless array of ownership structures in family firms. Some companies are owned by one individual, or by a couple, or by two unrelated partners. At the other end of the complexity scale are companies owned by combinations of family members (sometimes numbering in the hundreds), public shareholders, trusts, and other companies. For this dimension, as for the other two, the model strives for useful simplicity. No model of such a complex phenomenon can present categories that are completely exhaustive and nonoverlapping. However, we have found that the core issues of ownership development are well captured in three stages: Controlling Owner companies, Sibling Partnerships, and Cousin Consortium companies. These three categories help the professionals who are working with family businesses to make some critical distinctions between companies of different types, and help families themselves to understand how their current ownership structure affects all the other aspects of business and family operation. The ownership developmental dimension is discussed in chapter 1.

This dimension is not just three categories; it also assumes an underlying developmental direction. It suggests that most businesses begin with the single owner.12 Many family businesses then move, over time, through the Sibling Partnership to the Cousin Consortium. This is not to say that family companies always follow this sequence. In fact, many companies are founded and owned by combinations of more than one family generation and may transition from any combination to any other. For example, replacing an individual owner-manager with a single successor from the next generation is one type of succession, which in this model would be represented by a Controlling Owner company remaining at that stage. But that is not the only possibility. Some controlling owners distribute their holdings to two or more of their offspring, creating a Sibling Partnership. Some Sibling Partnerships, in turn, distribute ownership to a Cousin Consortium, or restrict it to a next-generation Sibling Partnership. And both of the later forms can recycle to the Controlling Owner stage if a single individual buys out all the others and reconsolidates ownership. The addition of multiple-family ownership groups, nonfamily shareholders, classes of stock, trusts, and annuities adds spice to individual cases. However, these three developmental stages still explain most of the variance across the widest range of companies. At any point in time, most family companies can be located primarily in one of the three stages, and there is an underlying developmental dynamic that pulls them through the generational sequence from Controlling Owners toward Sibling Partnerships and then Cousin Consortiums. That is why the ownership developmental dimension is the first in this model of family business.

Figure I-4 ■ The Ownership Axis

The Family Developmental Dimension

The model’s second dimension describes the development of the family over time. This dimension captures the structural and interpersonal development of the family, through such issues as marriage, parenthood, adult sibling relationships, in-laws, communication patterns, and family roles. To conceptualize individual and family development, we looked to the pioneering work on normal adult development by Daniel Levinson and his colleagues and to the many fine theorists studying family life cycles.13 Dividing business families into developmental subgroups helps sort out the enormous variety of business-owning families. Although there is variability in and overlap between stages, we saw that families within a stage had much in common. We also saw that the transition from one stage to another was a recognizable, meaningful moment in a family’s developmental history. The families that we work with respond immediately to the concept of change over time. They recognize themselves in the descriptions of the various stages. The sense of similarity with other family firms in the same stage is at once enlightening and reassuring. They find it particularly useful to learn about the challenges that likely await them in later developmental stages, so that they can anticipate and prepare for the future.

After considering the life histories of hundreds of business-owning families of all sizes and types in light of these developmental theories, we found that business families could be usefully divided into four stages, defined by the ages of the members of each generation active in the business. We call these stages Young Business Family, Entering the Business, Working Together, and Passing the Baton (figure I-5).

The first stage, Young Business Family, is a period of intense activity, including defining a marital partnership that can support the owner-manager role; deciding whether or not to have children and raising them; and forming a new relationship with aging parents. Returning to the four-part example that began this section, Ben Smith A is concerned primarily with resolving his continuing conflict with his father and becoming the business leader in fact as well as in name. His wife is troubled by the demands of the business. She needs his involvement in the family circle as well, in order to cover the tasks of home building and child rearing, and perhaps to allow her to pursue her own career dreams. The YBF stage presents parents with all the dilemmas of early adulthood as defined by Levinson’s adult development model: creating a dream of the future, exploring alternative lifestyles, establishing credibility, committing to a career and, most often, to a family role, and finally “becoming one’s own person” in the late thirties.14

At one stage farther up the axis, in Entering the Business, each generation is ten to fifteen years older than in the Young Business Family stage. This is the stage when families have to nurture the movement of the younger generation out of childhood and into productive lives as adults. EB families are concerned with creating entry criteria and career paths for the young adult generation, which include deciding whether or not to join the firm; with working on midlife transition issues as a couple and as siblings; and with defining a role as the middle of three adult generations, between elderly surviving parents and children who are getting ready to form families of their own.

Figure I-5 ■ The Family Axis

As is common in business families, Ben Smith B has to manage not only his own children’s entry into the company, but that of his siblings’ children as well. As the owner-manager moves through his or her forties, this is often the time of learning the first lessons of “letting go”; that is, letting go of children as they become adults, letting go of direct control over all aspects of a more complex business, and letting go of some of the options for alternative lives. These are the challenges of the midlife transition.

As the parental generation moves through the decade of its fifties and the younger generation is in its twenties and thirties, the family is in the Working Together stage. In the Working Together stage, families are attempting to manage complex relations of parents, siblings, in-laws, cousins, and children of widely ranging ages. The capacity of the business system to support a rapidly expanding family is tested during these years, especially in two ways: can the company’s profitability keep up with the income and lifestyle needs of the whole family, and can the size of the business provide meaningful career opportunities for qualified family members?

Ben Smith C is in the enviable position of having a thriving business and two competent offspring in the company at this stage. Even so, the complexity of so many different career plans and personal agendas is putting a strain on his business. This is the stage that puts a premium on family communication and clear operating procedures. It is also the stage when many families become dramatically more complex themselves. There is now a whole new adult generation adding to the mix of marriage, divorce and remarriage, stepchildren and half-siblings, and grandparenthood. Working together is the goal, but it requires the skill of an orchestra conductor.

Finally, in the Passing the Baton stage, everyone is preoccupied with transition. Although succession is often thought of as a business issue, we have been impressed with its enormous importance in the family circle as well. There are choices to be made about the sharing or passing of leadership from senior to middle generations in all aspects of family life. Business families have the symbolic issue of management and ownership control in the business to help them focus on the basic developmental questions of aging and intergenerational relationships. If the family prepares well and has the strength to overcome the many resistances to these powerful changes, then the work of Passing the Baton can be completed successfully. In any event, ready or not—too early, too late, or at just the right time—transitions inevitably occur, and the cycles begin again.

Ben Smith D thought he had a sound transition plan, but it proves harder to separate from his business than he had expected. Thinking about retirement causes him to take a good look at how he is relating in general to his son and daughter, both of whom are entering middle age themselves. The buyout offer also causes him to reconsider his own financial security. Looking forward to his senior adulthood, which could easily stretch for twenty or more years beyond his retirement from the presidency of his company, makes him realize that this stage is truly a transition, not an ending, and that it requires more “strategic planning” than he had thought.

The family developmental axis traces the developmental cycle of one nuclear family. However, as will be discussed in depth in chapter 2, as business families become more complex, there will be more than one family life cycle going on at the same time. In fact, within businesses that have reached the Sibling Partnership and Cousin Consortium stages on the ownership axis, there may be family groups that are in two, three, or even all four of the family stages. The interplay of different family groups, all dealing with their own developmental issues, creates some of the most interesting dynamics in family businesses and is one of the areas where this kind of model can be the most helpful.

The Business Developmental Dimension

The final dimension describes the development of the business over time. Our description of this dimension is built on the work of a number of business life cycle theorists, including Neil Churchill, Eric Flamholtz, Larry Greiner, and John Kimberly.15 The maturity of the business enterprise has been overlooked in most writing about family firms. However, there is important variation in growth, product maturity, capitalization and indebtedness, nonfamily manager development, and internationalization, which arises from the stage of the business. In fact, we found that the business’s developmental stage often has a powerful but hidden impact on such decisions as sales of family shares to outsiders or the succession of family leadership.

Models of business life cycles generally make fine distinctions between the stages, marked off by specific changes in the organization’s structure and operations. This level of differentiation is too specific for the purposes of this three-dimensional model. Once again, a simple three-stage progression captures the essential, useful differentiation of business stages (figure 1-6); the variations within each stage will be discussed more fully in chapter 3. The first stage, Start-Up, covers the founding of the company and the early years when survival is in question. Whether for the business as a whole or for new business units as they are created in complex family conglomerates, it is undeniable that there is always a startup period with powerful, unique characteristics. Businesses in their first few years are different in important ways from the way they will be at any other point in their life cycles.

The second stage, Expansion/Formalization, covers a broad spectrum of companies. It includes all family companies from the point when they have established themselves in the market and have stabilized operations into an initial predictable routine, through expansion and increasing organizational complexity, to the period when growth and organizational change slow dramatically. This stage may last a few years or many years, even beyond a generation. It is the time when family companies try to shape the growth curve and emerging structure of the business to serve the needs of the evolving ownership group and the developing family. Family businesses at this stage experience both positive and negative consequences of growth: increased opportunities and sense of possibility, and the concurrent stresses and strains as the expanding company outgrows its infrastructure (sometimes over and over again). If the business is succeeding, new opportunities are created for owners to realize acceptable returns on their investment and for family and nonfamily managers to build careers with attractive levels of compensation, authority, and status. When the business stalls or declines during the Expansion/Formalization stage, the consequences are felt beyond the business circle. The ownership group and the family must reassess their commitment to the business.

Figure 1-6 ■ The Business Axis

The final stage on the business developmental axis is Maturity. This stage has its roots in market assessment, describing the point when a product has stopped evolving and the competitive dynamics shift to increasingly unprofitable battles over market share. We are using it to describe a stage of stasis in a family company, when operations are routinized to the point of automatic behavior and expectations about growth are very modest. We do not present this as an indefinitely sustainable end state, however. Even when a company operates with extraordinary efficiency and has a controlling position in the market, the forces of developmental change cannot be held at bay indefinitely. There are two ways out of the Maturity stage for a family company: renewal and recycling, or the death of the firm.

There are limits on the usefulness of a typology of anything as complex as family enterprise. This model does allow businesses to be categorized into types. However, too much emphasis on categorizing can lead to oversimplification. Family businesses are constantly in motion, and distinctions between stages blur. There are many “hybrid” conditions, as when ownership is shared across generations, or in a complex business that is comfortably in maturity with its original product, while it starts some new ventures and grows others. We are not interested primarily in reducing family businesses to rigidly defined types; that moves us away from true understanding of their special nature. The model’s best use is to provide a predictable framework for the development of family businesses over time in each dimension, and to suggest how a recognition of the current stage—and the combination of stages across ownership, family, and businesses—helps us to analyze the dynamics of any family firm.16

The chapters that follow explore the complex variety of individual companies, while focusing on the common elements that make a model possible. Part I (chapters 1 to 3) presents each of the three developmental dimensions in more detail. Part II (chapters 4 to 7) presents four classic types of family business and shows how their characteristics and key challenges are shaped by their stage in each of the developmental dimensions. Part III (chapters 8 to 9) distills some of the specific lessons we have learned from intervention with family businesses as guided by the model. These ideas are intended for the various professionals who are advisers to family firms and for the owning families themselves.

NOTES

Dreux 1990, 1992. A truly reliable data base that will give specific demographic information about the number and type of family firms has yet to be developed. This is in part because the major sources of such data, such as the census bureau and business directories, do not classify companies according to the family status of owners or senior management. In two excellent new efforts, Massachusetts Mutual Insurance and Andersen Consulting have begun to gather broad sample survey data (Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company 1994; Arthur Andersen & Co. 1995). When the facts are ambiguous, we prefer to use very conservative estimates.

Zeitlin 1976.

Collin and Bengtsson 1991; Donckles and Fröhlich 1991; Lank 1991.

Chau 1991.

Lansberg and Perrow 1990.

Some of the earliest publications include Calder 1961; Donnelley 1964; Levinson 1971; Barry 1975; Danco 1975; and Barnes and Hershon 1976.

Beckhard and Dyer 1983; Lansberg 1983.

There has been some very interesting discussion in the literature about the relative balance between sub-system and whole-system analysis. See Kepner 1983; Hollander and Elman 1988; Benson, Crego, and Drucker 1990; and Whiteside and Brown 1991).

Tagiuri and Davis 1982.

This form of family diagram is called a “genogram.” It depicts the organizational structure of a family, indicating the age, gender, and family relationships of each individual. For more information on genograms, see McGoldrick and Gerson 1985.

Ward 1987, 1991.

As with all the stages in all three of the developmental dimensions, the titles given do not reflect all the variations in that stage. For example, although the stage is called “Controlling Owner,” in some cases a couple may own a business together, or there may be one dominant owner with a small number of other investors. The determinant of this stage is that one voice, usually one person, controls and speaks for ownership interests.

Levinson 1978, 1986, 1996. See also Erickson 1963; Vaillant 1977; Gould 1978; Gilligan 1982; and Levinson and Gooden 1985.

Levinson 1978, 144—165; 1996, 143—148.

Greiner 1972; Kimberly 1979; Kimberly, Miles, and Assoc. 1980; Churchill and Lewis 1983; Flamholtz 1986.

O’Rand and Krecker provide an elegant analysis of the utility and limitations of such “heuristic uses of the life-cycle idea” in the social sciences (1990, 259).