Are You an Investor from Lake Wobegon?

Are you a good driver?

Are you a good parent? Son or daughter? Sibling? Spouse/Boyfriend/Girlfriend?

How do you rate in your, er, more intimate activities?

Most people think they’re in fact pretty good in all of those categories. Certainly above average. But statistics tell us that, in fact, most people cannot be above average.

And the majority of investors think they’re above average in that skill too. No matter what their brokerage statements tell them.

It reminds me of Garrison Keillor’s Prairie Home Companion, which describes the fictional town of Lake Wobegon as a place where “all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all of the children are above average.”

In fact, a psychological term, the Lake Wobegon effect, is a bias in which people overestimate their abilities. Investors are notorious for this trait.

It’s unlikely that you (or anyone else) are a better-than-average investor. After all, even the pros stink out the joint most of the time.

According to Standard & Poor’s, the majority of mutual funds underperform their benchmark index in just about every category.3 More than 61% of large-cap funds failed to return as much as the S&P 500. Mid-caps were even more of a disaster with nearly 79% of funds underperforming.

Fund managers who went for growth were even worse. 88% of mid-cap growth managers, 80% of large cap, and 74% of small cap missed the index benchmark.

That means investors would have been better off investing in an index fund or exchange-traded fund that tracks the index rather than trusting the manager to beat the market.

So if these men and women who spend ten hours a day or more in the markets can’t succeed, isn’t it highly unlikely that you’ll be a better stock picker than they will?

The data shows that you won’t—at least when it comes to timing.

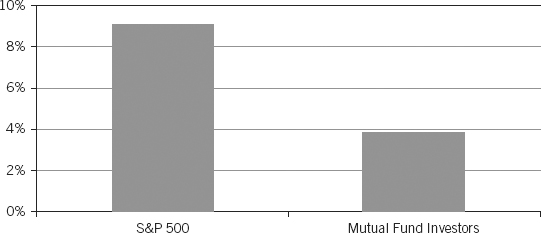

According to the DALBAR Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) study, from 1990 to 2010, the S&P 500 gained an average of 9.14% per year while the average equity fund investor saw profits of only 3.83% per year—not even enough to keep up with inflation.

What the study in Figure 3.5 shows us is that mutual fund investors are buying and selling at the wrong times. They buy when the markets get hot and sell when they fall, the exact opposite of what they should be doing.

Figure 3.5 1990–2010: Equity Mutual Fund Investors’ Poor Timing Leads to Subpar Results

Source: DALBAR, Inc., “Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior, 2011”

The remedy is to not be an active stock picker. Buy stocks that fit the criteria in this book and leave them alone for ten or 20 years. Trying to trade in and out of the market is a fool’s game. Do you really know when Intel is going to miss earnings or when the market is about to tank?

Invest in great companies that raise their dividends every year and don’t do anything else. In several years you will have many times more money than if you try to trade the market or put it in an actively managed mutual fund.

One other thing to consider in light of the fact that I just shattered your self-image as the next Warren Buffett: When you invest in dividend-paying stocks, you’re often more than halfway to matching the market’s return.

The market historically appreciates an average of 7.48% per year. If you own a stock with a dividend yield of 3.75%, you’re already halfway there. You don’t have to be Warren Buffett. In fact, you can be a lousy stock picker, one who invests in stocks that go up only half as much as the market, and you’ll match the performance. And if you reinvest the dividends, you’ll do even better.

If you invest in a stock with a 5% yield, you only need a gain of a few percentage points during the year to beat the market and the vast majority of professional investors, including the hedge fund manager with the $20 million New York penthouse apartment, $3,000 suits, and the 120-foot yacht. You’re likely beating that guy.

But investors aren’t the only ones who overestimate their abilities. Some CEOs think they can generate a better return for investors instead of giving some of that cash back. And, often, they’re wrong.

DePaul University’s Sanjay Deshmukh, Anand M. Goel, and Keith M. Rowe created a model for determining whether a CEO is “overconfident” or “rational.”4 In their research, they concluded that “an overconfident CEO pays a lower level of dividends relative to a rational CEO.” Interestingly, overconfidence tends to be seen more often in companies with lower growth and lower cash flow. Exactly the kind of companies where a CEO should not be overconfident.

Additionally, the market reacts with less enthusiasm to dividend announcements by companies headed by overconfident CEOs, suggesting perhaps that investors can sense the guy is a blowhard and are turned off by his management style.