41

Chapter Four

Stories About the

Warmth of Cooperation

and the Big Freeze

When Cooperation Flourishes: Jill’s Story

As soon as I walked into Jill’s office, I could hear the buzz; it was obviously a Hot Spot of energy and excitement, and Jill was Glowing. I wanted to know why. This is Jill’s story.

I am a very driven person. From an early age I knew what I wanted to be and have always worked really hard to get there. My passion was always for design. I love the process of thinking about something and then bringing it to fruition. For me the way I judge myself is the quality of my work—I have really high standards for myself and others and am known to push my colleagues really hard at times. When I was at design school, I was really focused on developing my own skills—I wanted to be the best designer in the college.

When I left design college, I joined a small design team. At first I loved the work, really relishing working on my own and bringing my ideas to fruition. Then I began to feel more and more uncomfortable. I found I was not sleeping very well at night and often felt a pit of anxiety in the stomach. I began to realize that one of the reasons was that people had begun to move away from me. At college we worked pretty much on our own, and I was used to doing my own thing. Here in the design studio I continued to work like this—getting in early in the morning, working on my project, and leaving late at night. I felt increasingly exhausted and isolated.

So in my late twenties I had to make a real choice about how I wanted to work. I began to realize that I was not seen as someone who could work easily with others. In fact, the rest of the team seemed to work well together, but I was excluded. I was seen as the person who worked only for herself, who liked to work on her own and to take all the credit. I realized that because I was working so hard on my own projects, I rarely noticed that others had great ideas as well and that there were occasions when my particular skills would be useful for the rest of the team.

For me the real shock came when at the end of six months’ work on a project, it came time to show the work to the clients. I was really pleased with mine and thought that it was the best piece of work I had done. I had used all my skills and worked incredibly hard. . . . So you can imagine how shocked I was at the reception the clients gave to my work. Although I had done the very best I could, there were two areas of the design that I had completely failed to understand. I had not really come to grips with how the product I’d designed could be manufactured, and the prototype I had created was going to be too costly to mass-market. It began to dawn on me that because I had worked so hard on my own, I had not had the benefit of my colleagues’ insights and knowledge of the manufacturing process and of costing feasibility.

Looking back, that client presentation was a life-changing event for me. I began to realize that if I was going to excel in the way I wanted to, I had to learn to cooperate with others in a more skillful and thoughtful way. I had to make cooperation my day-to-day habit, and I had to get better at listening to and conversing with others. I was lucky that on my team there was already a strong ethos and norms about cooperation. The team members often had lunch together, and they worked really hard to support one another. In fact, they even worked together to recruit new people to the design studio, each interviewing the person and then deciding together whether they would want to work with that person and how this potential recruit would add to the skills of the team. Once I set to work on it, I found it really easy to cooperate with others. For example, one of the practices we have is that whenever people visit our team from one of the other teams, we always try to have a brown-bag lunch for them and ask them to talk about what they are working on right now and what interests and fascinates them for the future. My team has been doing this for some time now, and I guess it is just the way that we do things around here.

I have also noticed how well the people on the senior team get on with one another. Don’t get me wrong—it is not all a bed of roses, and sometimes there are some really deep disagreements. But you can see that they respect and trust each other and have the best interests of the studio at heart.

43

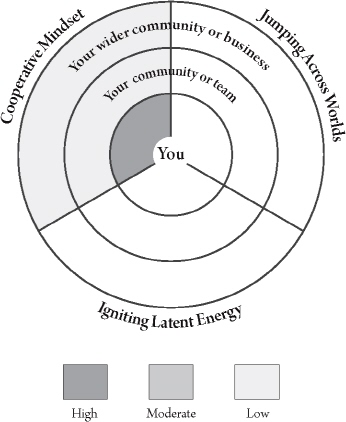

What strikes you about Jill’s story? Did you hear in it echoes of Fred, who also thought that success would come from hunkering down and minimizing his relationships with colleagues? What’s interesting about Jill’s story is that she had great resources working with her. Both her immediate colleagues and the place that she worked supported her to become more cooperative. So if you plot Jill’s cooperative profile in the three potential resources (herself, her colleagues and immediate team, and her wider community or business), as Figure 4.1 shows, all three resources are helping her Glow

44

FIGURE 4.1 Jill’s Cooperative Profile.

Looking back at your own cooperative profile, how similar is it to Jill’s? The interesting part of Jill’s story is that she did not start out cooperative. In her initial art school training, she had been encouraged to work independently of others. When she began work, she brought this mindset with her and continued to work in an independent way, regarding others as her competition. What changed Jill was the debacle of the client presentation.

This was a real “crucible experience” for Jill and a wake-up call about how she might have to change her attitudes and skills. This experience taught her that she was not going to be able to become what she wanted without the support of others.

45

FIGURE 4.2 Jill’s Virtuous Cycle

This was so important to her that she vowed to develop cooperative habits. Jill had to learn to be cooperative with others, despite the fact that she had been trained to compete rather than cooperate.

What really helped Jill develop these cooperative habits was that she worked on a team that practiced cooperation. Her colleagues listened to each other; they were prepared to give each other time and on occasions worked to support each other. The third part of Jill’s work life—the design company where she worked— is also very cooperative. Cooperative practices abound. People are selected on the basis of their ability to work as a team, and the brown-bag lunches provide a great informal place for conversation. At the same time, the senior team set strong cooperative role models through the way the members work with one another. In a sense, all three parts of Jill’s work life are now aligned around cooperation.

What has happened to Jill is that all three potential resources (her own attitudes and skills, her team and colleagues, and the company) are working together in what has become a virtuous cycle. This virtuous cycle is shown in Figure 4.2.

46

Jill has joined a design agency that believes in cooperation. In a sense, the place in which she works has been designed for cooperation. This is apparent in the way in which the whole team recruits new joiners, the habit of meeting informally for brown-bag lunches, and the open plan of the office, which encourages people to meet informally. All these are subtle ways of encouraging cooperation. As Jill spends more time in the company, she begins to behave in a more cooperative way. It becomes increasingly the norm for her to trust and support others and to expect them to trust her. So the language she uses is the language of cooperation; she uses words like we and colleague and cooperation.

So even though Jill worked on her own for her first six months at the company, as the tasks became more complex, she needed to focus on being more cooperative. Jill has been given a wonderful opportunity to Glow at work and to use her cooperative mindset as the basis of creating, finding, and flourishing in Hot Spots.

Reflecting on Jill’s Story

As you think about Jill’s story, ask yourself three questions:

- How would you describe your initial education and training— was it like Jill’s, encouraging you to compete with others and not develop the habits of cooperation? Action 1, developing the daily habits of cooperation, can help you learn how to build cooperation even if you have not been trained for it (see Chapter Five).

- On what basis have you decided whether to join a network, business, or community? Jill was lucky to join a cooperative community—but as we shall see in John’s story, others are not as fortunate. If you want to be more sophisticated about how you choose, Action 3, acting on the “smell of the place,” provides tips and questions on how to do this (see Chapter Seven).

- Have you ever had “crucible experiences” like Jill’s client meeting, when events go badly wrong? Looking back on those experiences, what can you learn from them—and is the basic problem, as in Jill’s case, one of lack of trust and goodwill?

47

When the Big Freeze Emerges: John’s Story

Although Jill started her career with a highly individual and independent mindset, over time she used all three potential resources available to her to create a work life that enabled here to Glow. Her profile is similar to what was identified as Profile Type A in Chapter Three. Looking back on Jill’s story, her crucible experience was the client meeting, which served as the wake-up call she needed to push her to develop cooperative habits.

But what happens when the resources around you do not encourage you to cooperate and Glow? When you are in a place where there is very little support for cooperation? When you are in Profile Type C? This is what happened to John.

Some years ago I was invited to advise a business that seemed to have much going for it. The mission of the business was to create innovative products in financial services and to act as a boutique for a couple of industry sectors. The founders had done everything they thought they should. They had carefully and systematically recruited clever people and some real experts to run the business. However, as I worked with the business, it became clear to me that all was not going according to plan. The hoped-for innovations were not taking place, and clients complained that they were disappointed with the people they worked with. They just did not have the sparkle the clients had expected. And it was not just the clients who were disappointed. I checked the turnover of talented people and saw that it was high. In fact, over the previous year, the business had lost four of its most talented young people. I began by talking with some of the younger people on the teams and also took a closer look at how people behaved toward one another on a daily basis. As part of the interview cycle I spoke with John—and subsequently followed up with him over the next six months. This is John’s story.

I did well in college. My grades were always good, and I was seen as a great student. I loved sports and spent much of my time outside of studying on the sports field. My specialty was the track events, and at one stage I got through to the college finals. I was really proud of what I had achieved.

48

When I left college, I joined one of the boutique financial firms. My job was to work as an analyst, so I had to collect and analyze data from companies in a given sector. In fact, I became something of an expert in the oil and gas sector. So I was delighted when after a year I was head-hunted to work with a newly formed financial research house. I was delighted to be part of the company; I knew the reputation of a couple of the founding partners and was very pleased to be working with them.

I have now been in the firm for two years, working as a research analyst in the oil sector. We tend to work separately as analysts. There are a couple of other people also specializing in the oil and gas sector, and I guess you would say we are in competition with each other. Every six months we each write a review of what we believe will happen in the sector, and the analyst with the strongest report is given a bonus.

Ours is a competitive firm. Each of the partners came from a different company, and they launched the business on the back of their expertise. The most important way to progress in the firm is to work with one of the founders—no one else really matters. I have a strong working relationship with Celia, one of the founders who specializes in the oil and gas sector. I spend a lot of time working on her clients. Some of my colleagues are somewhat jealous of this working relationship, but I know that finding a sponsor will be key to being promoted at the firm. By working with Celia, I get to know stuff that they don’t. But I am always careful to keep this knowledge to myself; I don’t want to let her down.

I guess I don’t feel great about working here. Sometimes the sheer competition between us gets me down. I cannot really talk with others about what they are doing because we are all in competition with each other. We use a lot of battle talk around here—winners and losers. We call our rooms “war rooms,” and when we make a sale to a client, we call it “taking the big game down.” It can be fun at times, but lots of people cannot take it and leave. I guess I am hoping going to get the most out of it before I move on.

49

FIGURE 4.3 John’s Cooperative Profile

John is not Glowing, and he is in a place where the Big Freeze is definitely taking its toll. How did this happen? John’s personal beliefs, his team, and his wider community are not resources that are helping him Glow. He and his colleagues see each other in an instrumental way—“What can this person do for me?”—and in a highly competitive light—“How can I do better than the others?” His cooperative profile is shown in Figure 4.3.

John has failed to build the virtuous cycle that Jill has and that you saw in Figure 4.2. Instead he is caught in a vicious cycle that is becoming increasingly “dog eat dog.” John was trained to be competitive, but unlike Jill, he did not have a crucible experience that forced him to look inside himself. He also joined a company where competitiveness is the norm. The place is designed for competition; you can see it in the way people behave toward one another and in the ranking and bonus systems. The language is the language of competition. John and his colleagues use the word I more than we; they argue strongly from their own corner and have little trust in others. The normal way to behave is competitively—these competitive norms encourage John and his colleagues to negotiate with each other; they engage in “tit for tat” conversation and always work for their own self-interest. As self-interest rather than cooperation becomes the normal way of behaving for John, he and his colleagues come increasingly to regard knowledge as power. So they begin to hoard rather than share knowledge. The Big Freeze will begin to take over. With the Big Freeze will go any opportunities for John to work with others and combine his expertise and knowledge as Jill was able to do when she created something novel and learned to Glow. The cycle illustrated in Figure 4.4 gives you an idea of how the momentum of self-interest eventually leads to a Big Freeze.

50

On the face of it, you would imagine that John’s company is a place where innovation and Hot Spots would flourish. It looks like it should be productive. John heard the words of competition, words like battlefields and wars and tournaments and winning. He saw these words as epitomizing power and energy and believed them to be harbingers of productivity and innovation. However, they turned out not to be. Instead, this is a place where knowledge is hoarded and negative competition is rife. Working in this company, John has lost his capacity to collaborate with others and has begun to lose trust in others. The competitive nature of John’s company has pitted him against his colleagues, so he sees competition around each corner and begins to be a little paranoid about the world; he no longer Glows.

There are some of the same elements here as in Fred’s story. Remember how he closed the door and vowed to work harder and harder? Like Fred, John’s energy and emotional strength are beginning to be sapped by his own attitudes and his workplace. His paranoia saps his emotional energy and destroys the possibility of friendships. His emotional state also stops him from sharing his ideas with others.

51

FIGURE 4.4 John’s Vicious Cycle

The interesting reflection here is that while on the face of it, such gung-ho, macho environmentsgive the impression that competition drives growth, yet in reality, they serve only to destroy the relationships, collaboration, and trust that are so crucial to Hot Spots and the possibility of anyone learning to Glow.

Thinking about Jill’s and John’s stories, what I find striking is how similar they began. Both Jill and John are the products of an education process that favors working individually. However, their paths took different routes when they left college and began to work. Jill joined a team and a company where over time she developed the habits and practices of cooperation. John’s career took a different path. In his company, he expected to work individually and competitively with his colleagues. His performance was pitted against others, and so he failed to develop the habits of cooperation.

Reflecting on John’s Story

As you think about John’s story, ask yourself three questions:

- What is your basic attitude about how you are going to be successful? Take a look at your competitive profile and see how you scored. Are you like John in believing that your success will come through competing with others?

- How do your colleagues on your immediate team behave toward one another? Are they, like Jill’s colleagues, likely to be potential resources for you? Or are they like John’s colleagues, likely to work against you? Remember that in a highly competitive world, everyone is competing with each other to Glow. In a cooperative world, everyone is helping each other Glow.

- If you are surrounded by highly competitive people, where can you start? One thought is to look at Action 1, developing the daily habits of cooperation, to identify how you can make the first move to change the nature of the place (see Chapter Five). Also take a look at Action 2, mastering the art of great conversation, to consider how you might begin the conversation (see Chapter Six).

52

Jill’s cooperative profile is aligned around cooperation, while John’s is aligned around competition. What happens when you find that you want to be cooperative but are surrounded by competitive people? That’s what Gareth found.

When a Cooperative Person Ends Up

in a Big Freeze: Gareth’s Story

As soon as you meet Gareth, you know he is one of life’s naturally cooperative people. Well-spoken, he handles himself with grace and ease. His voice rarely rises in tempo, and he has a reputation for fairness. This is his story.

54

Gareth’s cooperative profile is shown in Figure 4.5. As you can see, Gareth is a cooperative person who found himself in a highly competitive place where he was not succeeding and certainly not Glowing. In fact, it sounds as if he ended up in the Big Freeze, the sort of dog-eat-dog place John also found himself in.

Gareth made one big mistake: he left his old team and company to join another business without understanding what he was getting himself into. As a result, he ended up working in a highly competitive place where he was exploited for his good nature.

55

FIGURE 4.5 Gareth’s Cooperative Profile

Reflecting on Gareth’s Story

As you think about Gareth’s story, ask yourself three questions:

- Think back to your first job. Did it encourage you to be cooperative, or were you encouraged to compete with others?

- Have you ever found yourself on a team or in a community or business where you felt out of sync with everyone else? Like Gareth, have you ever tried to cooperate and simply ended up feeling exploited? If that’s the case, you need to become much savvier about the teams and places you are thinking of joining before you join. As Gareth found, having these insights after you have joined is too late. If you are in such a situation, take a close look at Action 3 to see how you can avoid making the same mistake again and be savvier about where you join (see Chapter Seven).

- Have you had crucible experiences that really shook you up? If so, how have you used these experiences to help you grow and Glow?

56

Now is the time to reflect on your cooperation profile and to consider which of the three actions discussed in Chapters Five, Six, and Seven are going to be most crucial to you.

Key Points in Chapter Four

Stories About the Warmth of

Cooperation and the Big Freeze

In these stories, we learned about three people and their experiences of cooperation. The key lessons from these stories are as follows:

- Some people, like Gareth, have learned to be cooperative from an early stage of their life, while others, like John, have been brought up to be competitive. These basic attitudes can be a resource that helps you Glow or an impediment that plunges you into the Big Freeze.

- However, even people like Jill who have been trained to be highly individualistic and competitive can learn new habits and skills. In Action 1, developing the daily habits of cooperation, you will see what Jill did to become more cooperative (see Chapter Five).

- Immediate colleagues and community are crucial resources inlearning new habits and skills. In Jill’s case, her immediate colleagues created a virtuous cycle in which the way they worked together, the language they used, and the norms of their behavior all created an atmosphere that encouraged Jill to be innovative, successful, and Glow.

- Your colleagues can also be a real block to Glowing. You saw this clearly in John’s story, when he foolishly joined a highly competitive team. That pitched him into a vicious cycle and made it more and more difficult to be energized, innovative, and successful. In Action 3, acting on the “smell of the place,” you will learn what John should have done before he joined and thereby avoided his error (see Chapter Seven).