Chapter 6

Harnessing Building Information Modelling (BIM) using the Plan

Why is the briefing process different on a BIM project?

How does a BIM project benefit from a well-assembled team?

How do the task bars and defined tasks in the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 benefit BIM projects?

What other aspects of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 are crucial on a BIM project?

Building Information Modelling (BIM) is radically altering the way that we design buildings. While early BIM projects harnessed the potential of emerging software to create buildings with more complex geometries, the acronym BIM is now being used as a wrapper to discuss many subject matters and as a catalyst for change.

In the UK, the Government Construction Strategy (published in May 2011, see www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-construction-strategy) has provided the impetus for many current BIM initiatives. A number of pilot projects are under way and new standards and protocols are being discussed, developed and published. The emergence of BIM has to be set within a broader context: the ongoing development of internet and associated technologies which are radically altering many business models (for example, consider recent changes to publishing, the music industry and the retail sector). Economist Jeremy Rifkin’s vision, in his publication The Third Industrial Revolution, is endorsed by the European Parliament and underlines the radical changes that are occurring.

Designers are finally reappraising their working methods. Computer-aided design (CAD) replicates the ‘analogue’ processes applied to the drawing board. BIM (despite its rather anonymous acronym) is championing a more revolutionary process and moving design into the ‘digital’ age. Although more long-winded, BIM might be better defined as ‘the means of harnessing technological change and developing new ways of briefing, designing, constructing, operating and using a facility’; in other words, creating a new Plan of Work.

At first glance, particularly for those accustomed to the jargon associated with BIM, the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 may not appear to be greatly influenced by BIM. However, the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 has been conceived in a manner that works with the most progressive of BIM projects. Conversely, the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 has also been devised to accommodate the transitional phase that allows a practice or project to incrementally change their working methods from analogue to digital.

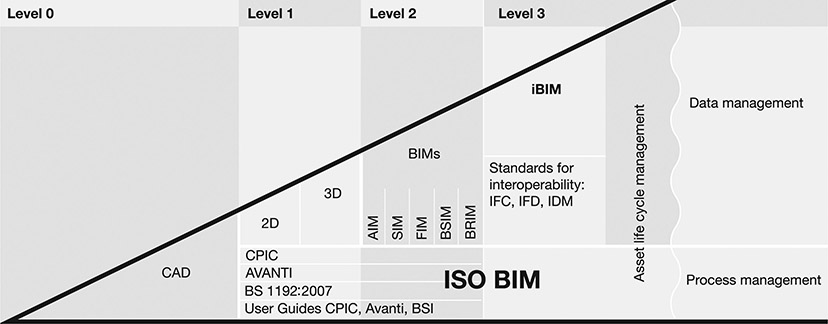

BIM Levels

Level 0 (L0)

Level 0 BIM is the use of 2D CAD files for production information; a process that the majority of design practices have used for many years. The important point to be derived from L0 is that Common Standards and processes in relation to the use of CAD failed to gain traction as the use of CAD developed.

Level 1 (L1)

![]() Level 1 BIM acknowledges the increased use of 2D and 3D information. For architects, 3D has increasingly been used as a conceptual design tool for analysis and development of more complex geometries and for visualisation of the finished project. This form of BIM, where only one party utilises the benefits of the model, is frequently referred to as ‘lonely BIM’. With L1, the use of 3D models by trade contractors also became more commonplace, with, for example, mechanical and electrical (M&E) contractors embracing BIM to enhance their design processes and to assist in the resolution of coordination issues during the design phase rather than waiting for the design to be realised on site. In terms of processes, L1 embraced the need for Common Standards to sit alongside design processes, including BS 1192:2007, Collaborative production of architectural, engineering and construction information – Code of practice.

Level 1 BIM acknowledges the increased use of 2D and 3D information. For architects, 3D has increasingly been used as a conceptual design tool for analysis and development of more complex geometries and for visualisation of the finished project. This form of BIM, where only one party utilises the benefits of the model, is frequently referred to as ‘lonely BIM’. With L1, the use of 3D models by trade contractors also became more commonplace, with, for example, mechanical and electrical (M&E) contractors embracing BIM to enhance their design processes and to assist in the resolution of coordination issues during the design phase rather than waiting for the design to be realised on site. In terms of processes, L1 embraced the need for Common Standards to sit alongside design processes, including BS 1192:2007, Collaborative production of architectural, engineering and construction information – Code of practice.

Level 2 (L2)

Level 2 BIM requires the production of 3D information models by all key members of the collaborative project team. However, these models need not co-exist in a single model. By understanding and utilising BS 1192:2007, designers can ensure that each designer’s model progresses in a logical manner before it is used by another designer or a designing subcontractor within the federated model (which combines the individual design team members’ models). It is not anticipated that the legal, contractual or insurance issues will change for L2 but it is fair to say that L2 BIM does expose some of the deficiencies of current contractual documentation. For example, the project roles need greater consideration and the allocation of design responsibilities between the various designers and contracting parties has to be clearer. The outputs, or Information Exchanges, at each stage will also require greater definition. L2 BIM requires better integration of the design team and the designing subcontractors, with collaborative project teams adopting Common Standards under new forms of procurement that employ ‘plug and play’ working methods.

Level 3 (L3)

With L2 acting as the boundary between analogue and digital processes, it is likely that there will be an evolution to L3 BIM rather than a leap. The boundary between L2 and L3 will see the development of:

- • early ‘rough and ready’ design analysis on environmental performance, minimising iterative design time

- • cost models that can be quickly derived from the model using new costing interfaces

- • automated checking of building models for Building Regulations compliance and/or other technical standards

- • methods of analysing health and safety aspects associated with the construction and maintenance of the building in parallel with the design, and

- • asset management, key performance indicators and other Feedback information aligned with intelligent briefing enabling information in the model to be developed during design and used as part of a more sophisticated handover (Soft Landings) approach and to inform and improve future projects.

Design processes will continue to be developed to their next level of refinement so that there are clear and established methods setting out how many parties can work in the same model environment at the same time. These processes will be aligned with better Schedules of Services and responsibility documents and ways of assembling the project team.

![]() The 2012 BIM Overlay to the RIBA Outline Plan of Work 2007 provided a useful overview of the different levels of BIM as defined in the Bew-Richards BIM maturity diagram in Figure 6.1, and highlighted the fact that, in order to progress to L2 BIM and onwards to L3, the following were required:

The 2012 BIM Overlay to the RIBA Outline Plan of Work 2007 provided a useful overview of the different levels of BIM as defined in the Bew-Richards BIM maturity diagram in Figure 6.1, and highlighted the fact that, in order to progress to L2 BIM and onwards to L3, the following were required:

- • collaborative and integrated working methods and teamwork to establish closer ties between all designers on a project, including designing trade contractors

- • knowledge of databases and how these can be integrated with the building model to produce a data-rich model incorporating specification, cost, time and facilities management information

- • new procurement routes and forms of contracts aligned to the new working methods

- • interoperability of software to enable concurrent design activities (for example, allowing environmental modelling to occur concurrently with orientation and façade studies)

- • standardisation of the frequently used definitions and a rationalisation of the new terms being developed in relation to BIM, and

- • use of BIM data to analyse time (4D), cost (5D) and facilities management (6D) aspects of a project.

Figure 6.1

BIM maturity diagram (source: © Bew and Richards, 2008)

![]() The 2012 BIM Overlay to the RIBA Outline Plan of Work 2007 also:

The 2012 BIM Overlay to the RIBA Outline Plan of Work 2007 also:

- • noted that better briefing, including Project Outcomes, was essential

- • highlighted the need for teams to be collaborative and integrated

- • stressed the need to define responsibilities, Schedules of Services and organograms early in the design process

- • underlined the need to refine old, and define new, project roles, particularly those related to design leadership

- • acknowledged the need to identify BIM procedures and protocols

- • emphasised the need to consider design responsibility

- • set out the possibilities for new post-occupancy duties

- • introduced the need for information drops and a delivery index (now Information Exchanges), and

- • considered the importance of Construction and Design Programmes.

The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 develops these themes further. There are two core statements that set out how the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 facilitates best practice in BIM:

Better briefing processes result in more effective designs that are more focused on the client’s objectives and desired Project outcomes.

Properly assembling the project team is the backbone of a collaborative team and results in each party understanding what they have to do, when they have to do it and how it will be done.

In this chapter we consider these two topics in greater detail.

Why is the briefing process different on a BIM project?

Briefing processes vary but their aim is the same: to obtain sufficient information from the client to allow the design process to commence in a constructive manner. The RIBA Plan of Work has always acknowledged that design is iterative and that aspects of the brief may develop as design solutions are developed. The information used to develop the Concept Design may include:

- • an area schedule defining the client’s spatial requirements

- • details of important spatial relationships (for example, between a kitchen and a dining space in a house or the waiting areas in relation to clinical spaces in a hospital)

- • information on subjective themes that are important to a client (for example, the building should be ‘accessible’, ‘light and airy’, etc.)

- • detailed technical requirements (for example, the number of sockets in rooms, lux levels or certain furniture or equipment to be accommodated in a room), and

- • budgetary considerations.

The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 does not change these fundamental requirements. However, it does split the briefing process into two stages: the Strategic Brief related to the client’s Business Case and the development of a detailed and specific Initial Project Brief.

The Strategic Brief tests the robustness of a client’s Business Case and may consider refurbishment, extension and new build options or compare the merits of a number of sites before objectively recommending the best approach. It may also look at strategic cost considerations: the overall area required, benchmark costs, level of specification and any abnormal costs that might arise from a specific site. By considering the project holistically, any strategic site, briefing or cost issues can be addressed before the detail of the project is developed.

Even on a simple project, these high-level considerations can save considerable time and money on abortive design work that might result from a flawed brief.

The 3D brief

With the Strategic Brief prepared, BIM can assist in the preparation of the Initial Project Brief. Using a 3D ‘block’ model allows the written brief to be developed in parallel with the Feasibility Studies. The linking of the geometric model to a spreadsheet containing the areas allows iteration between the developing 3D brief and the strategic area allowances. While using a 3D model, linked to a database, to prepare the Initial Project Brief allows a more intelligent and robust brief to be prepared, there is clearly a fine line between using such a tool for briefing and the commencement of the Concept Design.

The use of the BIM model as a briefing tool is also influenced by a number of other subjects that reinforce this approach and provide clues to how BIM will change design processes.

Reuse of assemblies

Hotel chains invest considerable time in determining the size of their rooms and what they will contain, including toilets, baths, showers, storage, furniture and detailed consideration of the interior design. Modular construction is increasingly being used on these projects, with completed rooms delivered to site. Although 3D geometry is not essential for such thought processes to work, stringent Feedback from previous projects and the reuse of design information from one project to the next reinforces the circular design processes, with one project acting as a catalyst for the next.

Healthcare providers are also seeing the benefit of fixing certain aspects of a project based on previous experience. For example, an operating theatre might be reused in its entirety on a future project, right down to the light, grille, equipment and socket locations. This reuse of assemblies (typically rooms) will become more commonplace as Feedback is harnessed more effectively.

In the future, clients who undertake repeat projects will increasingly provide briefs that specify the reuse of detailed assemblies from previous projects for certain areas, along with more traditional briefing for areas where they require a project-specific design solution, for example the lobby in a hotel.

Project Outcomes

Project Outcomes also require circular processes, albeit applied in a different manner. For Project Outcomes to be successful they need to be specified in a manner that can be measured when the project is completed. More importantly, datasets from a number of similar projects are required before benchmarking can be constructively applied to a project.

The data within the BIM models and the ability to analyse this information as it is refined demonstrates how BIM can provide a significant contribution to this subject.

Post-occupancy use of design information

Designers have traditionally prepared their information solely for the purpose of constructing the building or related activities, such as gaining planning consent. While operating and maintenance manuals might be prepared, these are typically static documents. Facilities management software interfaces are being developed that will require new briefing methods to ensure that the BIM model can be effectively used for the operation of a building and not just for its construction.

These examples are not intended to be definitive. They provide suggestions as to how practices might develop their own working briefing methods and processes using the RIBA Plan of Work 2013.

How does a BIM project benefit from a well-assembled team?

The documents set out in Chapter 3 for establishing the project team have been devised, in conjunction with the RIBA Plan of Work 2013, to be applicable to any project. They have been specifically devised with a BIM project in mind. The notion is simple: if time is spent during Stage 1 considering who will be doing what, when and how, the design process will be more effective when it commences. More crucially, once the boundaries between each designer have been properly defined, any ambiguities regarding roles or duties will be removed. Furthermore, each party can proceed with confidence that their fee reflects the work they will have to undertake. As a reminder, the process defined by the documents recommended in Chapter 3 ensures that:

- • the roles required on a project are properly considered

- • the timing of contractor involvement is thought through

- • management and design responsibilities are clear

- • Information Exchanges are defined

- • Project, Design and Construction Programmes are agreed, and

- project protocols are established.

The more specific aspects of this process that benefit a BIM project are:

- • ensuring that it is clear which software, including the specific version, is being used by each member of the team by early completion of the Technology Strategy to be included, or referenced, in the Project Execution Plan

- • agreement of the Communication Strategy and the means by which information will be distributed, commented on and developed within the project team

- • agreement of the project BIM manual, determining file structuring and naming protocols

- • use of the Handover Strategy to assist in the consideration of how BIM will be used during Stages 6 and 7, allowing the designers to include the relevant information within their BIM models as the design progresses

- • harnessing the Design Responsibility Matrix and the Information Exchanges so that it is clear who is responsible for each aspect of the design and the level of detail required at each stage (see further below).

Properly assembling the project team is only one aspect of creating a collaborative project team. Effective communication skills are essential for a project team to be truly collaborative and, while the communication skills of individuals will be invaluable, these skills can only come into their own if the team has been properly assembled at an early stage and their processes and protocols agreed in advance of design work progressing.

How do the task bars and defined tasks in the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 benefit BIM projects?

Chapter 2 sets out the reasoning behind the eight stages and eight task bars. Five of the task bars have been conceived specifically to facilitate BIM, as detailed below.

Procurement task bar

The Procurement task bar looks at procurement holistically and considers the procurement of the project team, which includes the design team and the contractor.

Programme task bar

Collaborative contracts, such as PPC2000 (a multi-party contract published by the Association of Consultant Architects), stress the importance of having an agreed Project Programme. Generating the programme collaboratively ensures that each party in the project team is aware of the reasoning for each period. The programme is particularly important on BIM projects because greater effort is required during the early design stages. Compressed design programmes reduce crucial set-up periods or the time required to successfully iterate the design. Overlapping activities or stages with other activities, such as Stage 4 and the period during which the planning application is being considered, generate substantial risk. Generating the Project Programme ensures that it is clear who is taking such risks.

Those generating the Project Programme should bear in mind the following:

- • BIM may reduce design time; however, no specific research has been published in relation to this and each practice will have to use their own experiences to make judgements regarding design periods.

- • BIM may reduce the number of iterations required by the design team to coordinate the design, in particular by harnessing collaborative working.

- • The need to properly set up a project team on a BIM project is vital and this period should not be compromised.

- • Although BIM may reduce design time, agreeing to reduce design time creates risks for the design team. Stringent design processes are required to manage this risk and Change Control Procedures should be adopted after the Concept Design has been signed off by the client.

Suggested Key Support Tasks task bar

The purpose of the Suggested Key Support Tasks is to underline the need for certain activities to occur. In terms of BIM, agreement of the Schedules of Services, the Design Responsibility Matrix and Information Exchanges and preparation of the Project Execution Plan, including the Technology Strategy, as part of the process of assembling the project team are the most important tasks (covered in greater detail on pages 75 to 77).

Information Exchanges and UK Government Information Exchanges task bars

The Information Exchanges task bar, and the associated task bar that sets out the UK Government’s Information Exchanges, play a crucial role in underlining some of the significant cultural changes required to implement BIM effectively. Information Exchanges and level of detail are considered further below.

What other aspects of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 are crucial on a BIM project?

While all of the activities within the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 are applicable to any project, certain activities have been specially developed with BIM in mind. In particular, the Design Responsibility Matrix, Information Exchanges (and the associated level of detail) and a number of aspects related to the Project Execution Plan are of particular relevance on a BIM project.

Design Responsibility Matrix

The Design Responsibility Matrix is an important BIM document, related closely to the level of detail, which is considered further below. The Design Responsibility Matrix addresses the issue of design responsibility between consultants in the design team, but, more importantly, it also addresses the design interface between consultants and the specialist subcontractors employed by the contractor.

The boundaries between structural and building services engineers and specialist subcontractors have been clarified in recent years and there are common expectations regarding the interfaces between the various designers. For the architect, specific components, such as curtain walling, are exceptions to the rule that there is no commonly agreed method of determining those aspects for which the architect retains design responsibility and those where design responsibility passes to a specialist subcontractor via the Building Contract. JCT Building Contracts have facilitated the prescription of such elements for some time. The RIBA Plan of Work 2013, through the inclusion of specialist subcontractor design in Stage 4 and the Design Responsibility Matrix, encourages greater consideration of this important subject.

The Design Responsibility Matrix is of particular importance on a BIM project as it ensures that every party with design responsibilities is clear regarding the design information they will be contributing to the federated BIM model and the level of detail that this model will contain. The matrix is of particular importance to the lead designer, who must ensure that it allows any design coordination obligations that are allocated to this role to be undertaken.

Federated model

A holistic model of a project consisting of models from each member of the design team that are linked together – the model may contain geometric and/or data information.

Information Exchanges (and level of detail)

Chapter 3 examined why consideration of Information Exchanges is a crucial matter in relation to the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 and how use of the Information Exchanges template in assembling a collaborative project team will facilitate this. It also clarified why level of detail is an important subject.

If we consider the typical development of a federated BIM model we can begin to understand the complexities of the subject:

- • The architect develops the concept design model and, following a number of iterations using rendered visualisations, achieves client sign-off.

- • The structural and mechanical engineers work on their models, with the lead designer providing comments, to ensure that the concept being presented is robust.

- • The iterative design process continues until all of the models are coordinated and cost-checked to confirm that the project is on budget.

- • The detail of each designer’s model progresses until it is sufficiently developed for use by specialist contractors to prepare their design models.

- • The specialist contractors develop their models, which are checked by the lead designer, who also ensures that they integrate with the coordinated design.

- • All design models are signed off and off-site manufacturing and onsite construction commence and continue until completion.

- • The client or a specialist facilities management company utilises the models for the day-to-day maintenance and running of the building.

Early contractor involvement may result in a more complex interface and overlap of designers’ BIM files and those prepared by specialist contractors. This scenario is based on BIM files being transferred between parties and also acting as the contractual information. The accuracy of the information in these files is therefore of paramount importance and the level of detail in each model needs to be appropriate for its purpose. Where the design baton is being handed over from designer to specialist subcontractor, the level of detail in the designer’s model must be sufficient for the specialist to progress their proposals.

Protocols determining the level of detail for BIM models therefore become essential tools for use on future projects.

Project Execution Plan

![]() A Project Execution Plan is a useful document on any project. In Chapter 3 the contents of this document were considered, and Assembling a Collaborative Project Team provides a further layer of information. In relation to BIM, reference is frequently made to a BIM Execution Plan or a BIM manual. The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 suggests that all of these documents are included or referenced in the Project Execution Plan. A number of aspects of the Project Execution Plan are of particular importance on a BIM project, as detailed below.

A Project Execution Plan is a useful document on any project. In Chapter 3 the contents of this document were considered, and Assembling a Collaborative Project Team provides a further layer of information. In relation to BIM, reference is frequently made to a BIM Execution Plan or a BIM manual. The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 suggests that all of these documents are included or referenced in the Project Execution Plan. A number of aspects of the Project Execution Plan are of particular importance on a BIM project, as detailed below.

Technology Strategy

Agreement of the Technology Strategy on a project is an essential first step because different parties involved in a project team will inevitably use different software packages. Despite a move towards interchangeable data formats (IFC), outputting data from one software format into another is not always possible or is liable to data loss or corruption. Regardless of the realities or legal issues associated with these technical points, the software to be used can have a significant impact on a project. If new software has to be adopted by one party, the issues of training and working to deadlines needs to be considered, depending on the importance and complexity of the software, and additional costs for purchasing software may also have to be built into any fee proposals.

The location of hardware can also have an impact, and particularly the location of the server containing the BIM files. Is every party working from this server, which might require a high-speed internet connection? If not, how are files shared? And in what format?

In conclusion, the Technology Strategy for the project team needs to be carefully considered to ensure that each member of the team is capable of working successfully with other members and that the implications of hardware and software are considered and agreed prior to appointments being made and design work commencing.

IFC

The Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) data model is an open and freely available (i.e. not owned or managed by a single software vendor) object-based file format. It was developed by buildingSMART (formerly the International Alliance for Interoperability) to facilitate interoperability in the architecture, engineering and construction industries and is a commonly used format for BIM.

Communication Strategy

The Communication Strategy is closely related to the Technology Strategy. For example, on an international project, video conferencing (part of the Technology Strategy) may be a core communication tool.

The purpose of the Communication Strategy is to consider the interface between meetings, workshops, email, file-sharing portals, procedures for commenting on drawings and other methods used in the iterative design process. The strategy must be flexible and ad hoc meetings, calls or other methods of exchanging information will also need to be adopted.

BIM manual

The BIM manual sets out file- and drawing-naming conventions and other processes in relation to BIM. A CAD manual is typically a single-party document whereas a BIM manual has to be considered and agreed by the collaborative project team and sets out project-wide conventions and processes. Agreement of the BIM manual (or any other name by which it may be known) is a core requirement in the development of a collaborative project team.

What is meant by ‘plug and play’?

Most architectural practices have their own CAD manual that sets out file- and drawing-naming conventions along with other internal CAD protocols. One of the disappointments of the CAD era is that no commonly adopted industry-wide documents or Common Standards exist (those that have been created have not been widely adopted). The concept of ‘plug and play’ envisages a scenario where practices can move seamlessly from one project to another and integrate collaboratively into many project teams without any changes to their internal BIM manual: an industry-wide BIM manual. The design development processes would be seamless. As project teams try to define common ways of working, the challenges in the short term will be significant. In the long term, it is likely that automated BIM processes will resolve the challenges associated with creating a ‘plug and play’ environment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, BIM and new digital technologies will drive cultural changes in the construction industry as we move from analogue to digital ways of working. In this guide, reference is made to how the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 facilitates a BIM project. For subjects still at an embryonic stage (level of detail, for example) we have highlighted the robustness of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 to accommodate future change as thinking around these subjects matures.