CHAPTER 26

Get Your Team to Do What It Says It’s Going to Do

by Heidi Grant

Say you’re in the early stages of planning your department’s budget for the next fiscal year. Your management team meets to establish short-term priorities and starts to think about longer-term resource allocation. You identify next steps and decide to reconvene in a week—but when you do, you find that very little progress has been made. What’s the holdup? Your to-dos probably look something like this:

Step 1: Develop a tentative budget for continuing operations.

Step 2: Clarify the department’s role in upcoming corporate initiatives.

Those steps may be logical, but they’re ineffective because they omit essential details. Even the first one, which is relatively straightforward, raises more questions than it answers: What data must the team gather to estimate requirements for continuing operations? Who will run the reports, and when? Which managers can shed additional light on resource needs? Who will talk to them and reconcile their feedback with what the numbers say? When will that happen? Who will assess competing priorities and decide which trade-offs to make? When?

Creating goals that teams and organizations will actually accomplish isn’t just a matter of defining what needs doing; you also have to spell out the specifics of getting it done, because you can’t assume that everyone involved will know how to move from concept to delivery. By using what motivational scientists call if-then planning to express and implement your group’s intentions, you can significantly improve execution.

If-then plans work because contingencies are built into our neurological wiring. Humans are very good at encoding information in “If x, then y” terms and using those connections (often unconsciously) to guide their behavior. When people decide exactly when, where, and how they will fulfill their goals, they create a link in their brains between a certain situation or cue (“If or when x happens”) and the behavior that should follow (“then I will do y”). In this way, they establish powerful triggers for action.

We’ve learned from more than 200 studies that if-then planners are about 300% more likely than others to reach their goals. Most of that research focuses on individuals, but we’re starting to uncover a similar effect in groups. Several recent studies indicate that if-then planning improves team performance by sharpening groups’ focus and prompting members to carry out key activities in a timely manner.

That’s an important finding, because organizations squander enormous amounts of time, money, ideas, and talent in pursuit of poorly expressed goals. If-then planning addresses that pervasive problem by sorting out the fine-grained particulars of execution for group members. It pinpoints conditions for success, increases everyone’s sense of responsibility, and helps close the troublesome gap between knowing and doing.

Overcoming Obstacles to Execution

Peter Gollwitzer, the psychologist who first studied if-then planning (and my postdoctoral adviser at New York University), has described it as creating “instant habits.” Unlike many of our other habits, these don’t get in the way of our goals but help us reach them. Let’s look at a simple work example.

Suppose your employees have been remiss in submitting weekly progress reports, and you ask them all to set the goal of keeping you better informed. Despite everyone’s willingness, people are busy and still forget to do it. So you ask them each to make an if-then plan: “If it’s 2 p.m. on Friday, I will email Susan a brief progress report.”

Now the cue “2 p.m. on Friday” is directly wired in their brains to the action “email my report to Susan”—and it’s just dying to get noticed. Below their conscious awareness, your employees begin to scan the environment for it. As a result, they will spot and seize the critical moment (“It’s 2 p.m. on Friday”) even when they’re busy doing other things.

Once the “if” part of the plan is detected, the mind triggers the “then” part. People now begin to execute the plan without having to think about it. When the clock hits 2 on Friday afternoon, the hands automatically reach for the keyboard. Sometimes you’re aware that you are following through. But the process doesn’t have to be conscious, which means you and your employees can still move toward your goal while occupied with other projects.

This approach worked in controlled studies: Participants who created if-then plans submitted weekly reports only 1.5 hours late, on average. Those who didn’t create them submitted reports eight hours late.

The if-then cue is really important—but so is specifying what each team member will do and when (and often where and how). Let’s go back to the budgeting example. To make it easier for your team to execute the first step, developing a tentative budget for continuing operations, you might create if-then plans along these lines:

When it’s Monday morning, Jane will detail our current expenses for personnel, contractors, and travel. If it’s Monday through Wednesday, Surani and David will meet with the managers in their groups to get input on resource needs.

When it’s Thursday morning, Phil will write a report that synthesizes the numbers and the qualitative feedback.

When it’s Friday at 2 p.m., the management team will reassess priorities in light of Phil’s report and agree on trade-offs.

Now there’s less room for conflicting interpretations. The tasks and time frames are clearly outlined. Individuals know what they’re accountable for, and so do the others in the group.

Does the if-then syntax feel awkward and stilted? It might, since it doesn’t reflect the way we naturally express ourselves. But that’s actually a good thing, because when we articulate our goals more “naturally,” the all-important details of execution don’t stick. The if-then construction makes people more aware and deliberate in their planning, so they not only understand but also complete the needed tasks.

Solving Problems That Plague Groups

Beyond helping managers get better results from their direct reports, if-then planning can address some of the classic challenges that groups face when working and making decisions together. Members often allow cognitive biases to obscure their collective judgment; for example, falling into traps such as groupthink and fixation on sunk costs. New findings suggest that if-then planning can offer effective solutions to this class of problems.

Groupthink

In theory, teams should be better decision makers than individuals, because they can benefit from the diverse knowledge and experience that each member brings. But they rarely capitalize on what each person distinctively has to offer. Rather than offering up unique data and insights, members focus on information that they all possess from the start. Many forces are at work here, but primary among them is the desire to reach consensus quickly and without conflict by limiting the discussion to what’s familiar to everyone.

Even when team members are explicitly told to share all relevant information with one another—and have monetary incentives to do so—they still don’t. When people are entrenched in existing habits, paralyzed by cognitive overload, or simply distracted, they tend to forget to execute general goals like this.

Research by J. Lukas Thürmer, Frank Wieber, and Peter Gollwitzer conducted at the University of Konstanz demonstrates how if-then plans improve organizational decision making through increased information exchange and cooperation. In their studies, teams worked on “hidden profile” problems—which required members to share knowledge to identify the best solution. For instance, in one study, three-person panels had to choose the best of three job applicants. Candidate A was modestly qualified, with six out of nine attributes in his favor—but every panel member knew about all six attributes. Candidate B also had six attributes in his favor, but every panel member knew about three of them, and each had unique knowledge of one additional attribute. Candidate C, the superior candidate, had nine out of nine attributes in his favor, but each panel member received information about only three attributes. To realize that Candidate C had all nine, the members of a panel had to share information with one another.

All the panels were instructed to do so before coming to a final decision and were told that reviewing the bottom two candidates’ positive attributes would be a good way to accomplish this. Half the panels made an if-then plan: “If we are ready to make a decision, then we will review the positive qualities of the other candidates before deciding.” (All study participants knew that the if-then plans applied specifically to them—and that the task needed to be done at that moment—so they didn’t spell out the who and the when, as they would have in real life.)

A panel that focused only on commonly held information would choose Candidate A—one of the inferior candidates—reasoning that he had six attributes as opposed to Candidate B’s four and Candidate C’s three. A panel whose members broke free of groupthink and successfully shared information would realize that in fact Candidate C had all nine attributes and choose him instead.

Not surprisingly, panels that made no if-then plan chose the superior candidate only 18% of the time. Panels with if-then plans were much more likely to make the right decision, selecting the superior candidate 48% of the time.

PLAN FOR THE UNEXPECTED

If-then planning is particularly useful for dealing with the inevitable bumps in the road—the unforeseen complications, the minor (and major) disasters, those moments when confusion sets in. Studies show that people who decide in advance how they will deal with such snags are much more resilient and able to stay on track.

Begin by identifying potential risks, focusing on those that seem the most likely. If the new project management software you purchased turns out to be buggy or the new review process you’ve implemented is too cumbersome, what will you do? If a major supplier goes out of business or has a factory fire, will you have sufficient reserves on hand?

To create contingency if-then plans, you identify what action to take should one of those risks turn into a reality. Suppose your business unit is market testing two new product lines. Rather than assume that at least one of them will merit further investment, make an if-then plan that allows for a less optimistic outcome. For instance: “When we have third-quarter sales figures in hand, Carol will calculate ROI and build a business case for next-phase funding.”

Clinging to Lost Causes

Further studies by Wieber, Thürmer, and Gollwitzer show that if-then plans can help groups avoid another common problem: committing more and more resources to clearly failing projects. As the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman and his collaborator Amos Tversky pointed out decades ago, we tend to chase sunk costs—the time, effort, and money that we have put into something and can’t get back out. It’s irrational behavior. Once your team realizes that a project is failing, previous investments shouldn’t matter. The best you can do is try to make smart choices with what you have left to invest. But too often we stay the course, unwilling to admit we have squandered resources that would have been better spent elsewhere. Groups, especially, tend to hang in there when it would be best to walk away, sometimes doubling down on their losing wagers. And the more cohesive they are, the greater the risk.

The dangers of identifying too much with one’s team or organization are well documented: pressure to conform, for instance, and exclusion of atypical group members from leadership positions. When being a “good” team member is all that matters, groups often (implicitly or explicitly) discourage diverse ways of thinking, and they’re loath to acknowledge their imperfections and errors of judgment. Hence the blind spot when it comes to sunk costs.

However, by taking the perspective of an independent observer, a group can gain the objectivity to scale back on its commitments to bad decisions or cut its losses altogether. In other words, by imagining that some other team made the initial investment, people free themselves up to do what’s best in light of current circumstances, not previous outlays.

Wieber, Thürmer, and Gollwitzer hypothesized that if-then planning might be a particularly good tool for instilling this mind-set, for two reasons. First, studies showed that if-then plans helped individuals change strategies for pursuing goals, rather than continue with a failing approach. Second, additional research by Gollwitzer demonstrated that making if-then plans helped people take an outsider’s view (they assumed the perspective of a physician when seeing blood in order to reduce feelings of disgust).

To test the effectiveness of if-then plans in scaling back group commitments, a study led by Wieber put subjects into teams of three and asked them to make joint investment decisions. Each team acted as a city council, deciding how much to invest in a public preschool project. During phase one, the groups received information casting the project in a very positive light, and they allocated funds accordingly. In phase two, they received both positive and negative information: Construction had begun and a local store was donating materials, but the building union wanted a substantial raise and environmental activists had voiced concerns about the safety of the land. Rationally, the teams should have begun to decrease funding at this point, given the uncertainty of the project’s success. Finally, in phase three, the groups received mostly negative information: Oil had been found in the sand pit, parents were outraged, and fixing the problems would be time-consuming and expensive. Further scaling back was clearly called for.

So what did the teams do? Those that had made no if-then plans showed the typical pattern of commitment. They slightly increased the percentage of budget allocated to the project from phase one to phase three. In contrast, teams with if-then plans (“If we make a decision, we will take the perspective of a neutral observer that was not responsible for any prior investments”) reduced their investments from phase one to phase three by 13%, on average.

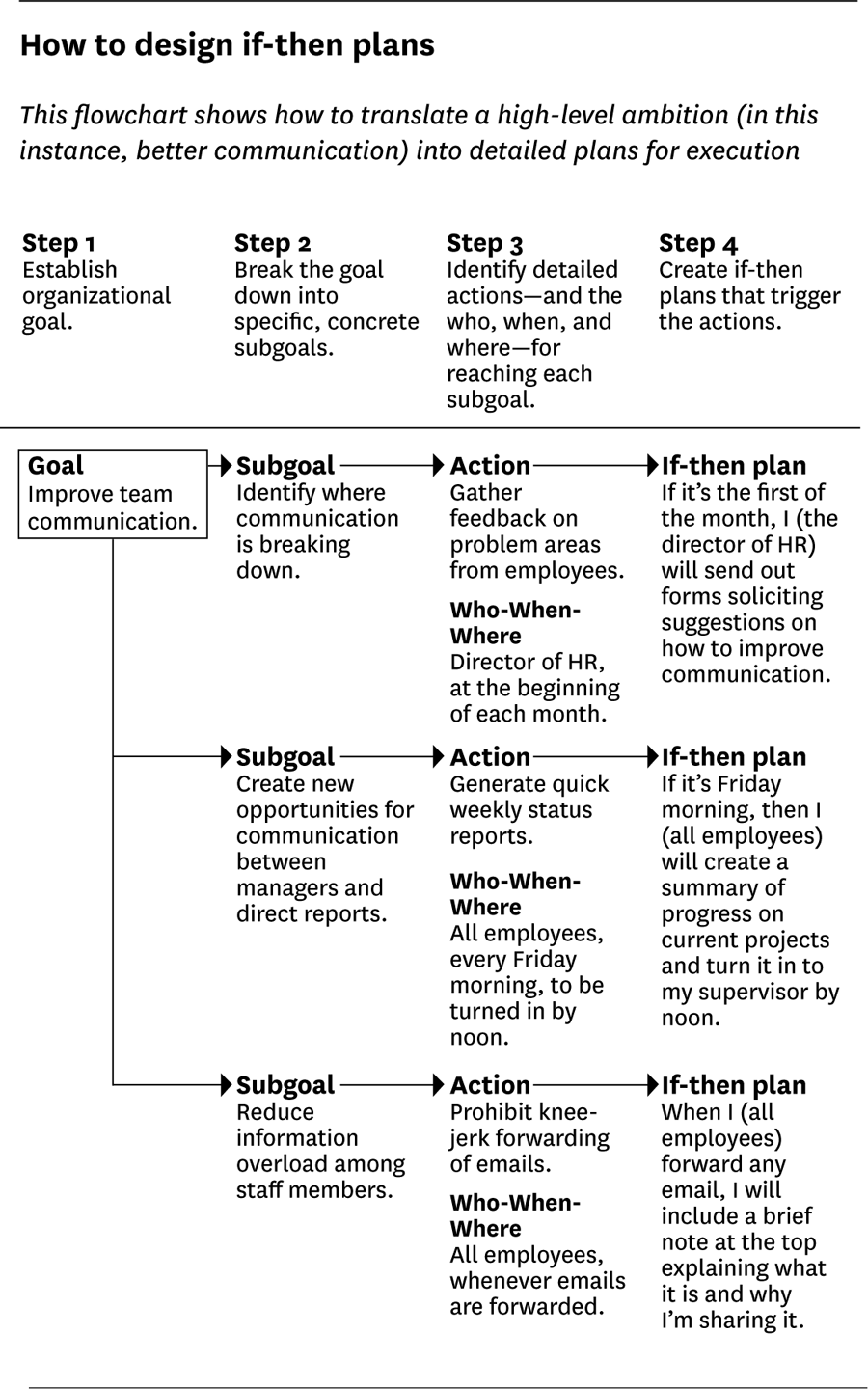

When teams and organizations set goals, they tend to use sweeping, abstract language. But it’s easier to frame your plans in if-then terms if you first break them down into smaller, more concrete subgoals and then identify the actions required to reach each subgoal. (See figure 26-1, “How to design if-then plans.”) If you were trying to improve your team’s communication, for example, you might set “Reduce information overload among staff members” as one subgoal. And after some brainstorming, you might decide to accomplish that by asking members who are forwarding any email to explain up front why they’re doing so. (The rationale: People will be more selective about what they pass along if they have to provide a reason.) The if-then plan for each team member would be “If I forward any email, I’ll include a brief note at the top describing what it is and why I’m sharing it.” One manager I spoke with found that this if-then plan put an immediate end to the knee-jerk forwarding that had clogged everyone’s inbox with unnecessary information. It also increased the value of the emails that people did forward.

Specifying the who, when, and where is an ongoing process, not a onetime exercise. Ask team members to review their if-then plans regularly. Studies show that rehearsing the if-then link can more than double its effectiveness. It also allows groups to periodically reassess how realistic their plans are. Is anything harder or taking longer than expected? Are there steps that the team didn’t plan for? If circumstances change, your if-then plans need to change, too—or they won’t have the desired impact.

Though the research on if-then planning for teams and organizations is relatively new, the early results are promising, and social psychologists are examining several uses and benefits. (For instance, I’m studying whether it can be used to shift group mindsets from what I call “be good” thinking to “get better” thinking that fosters continuous improvement.) What’s already becoming clear is that if-then planning helps groups frame their goals in a way that’s achievable, providing a bridge between intentions and reality. It enables them to do more of what they mean to—and do it better—by fostering ownership and essentially reprogramming people to execute.

__________

Heidi Grant, PhD, is Senior Scientist at the Neuroleadership Institute, and associate director for the Motivation Science Center at Columbia University. She is the author of the bestselling books Nine Things Successful People Do Differently (Harvard Business Review Press, 2012), No One Understands You and What to Do About It (Harvard Business Review Press, 2015), and Reinforcements: How to Get People to Help You (Harvard Busines Review Press, 2018). Follow her on Twitter @ heidgrantphd.

Reprinted from “Get Your Team to Do What It Says It’s Going to Do” in Harvard Business Review, May 2014 (product #R1405E).