2

History, Heresy, Hacking

Hacking’s origin is well understood, and its origin myths legion. Phone phreaking—using audio tones to make free phone calls, to the dismay of Ma Bell—is one activity that stands out in hacking lore. (The hacker publication 2600 is named for the hertz frequency used to control the phone system.) Another famed locus of proto-hacking is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus, where obsessed students stayed up nights building elaborate model train systems, stringing together novel electronics, and prowling the campus using its network of infrastructure tunnels.1 Though these examples are somewhat divergent, they are more similar than they are different: both began in the late 1950s and placed adventure-seeking, curious, youngish white men at the center of the action. And, by extension, this is the subject position we imagine when we think of a hacker: located at the center of technical culture, the hacker stretches the limits of technologies to flex his curiosity and assert agency.

This genealogy is important as we examine how voluntaristic technical communities grapple with patterns of participation among their ranks. This book takes the perspective that technical communities and their activities are co-constitutive. In other words, changing who is there may also change practice, and vice versa. This disputes widely held assumptions that technical practices like coding or tinkering constitute a neutral palette.2 It also argues that for those whose social positions deviate from the norms around which the categories of geek or hacker have been called into being, negotiation with these categories is required.

Geeks and Hackers

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines geek as “depreciative. An overly diligent, unsociable student; any unsociable person obsessively devoted to a particular pursuit.”3 This usage goes back to at least the 1950s. The OED offers a more recent, 1980s, definition of geek as “a person who is extremely devoted to and knowledgeable about computers or related technology,” and notes that “in this sense, esp. when as a self-designation, not necessarily depreciative.” Another iteration of the term meant a carnival performer or circus freak. This usage is a bit earlier, with the OED listing 1919 for a carnival performer and 1935 for the colorful description “a degenerate who bites off the heads of chickens in a gory cannibal show.” Precedent for both the circus geek and the academic geek is found in nineteenth-century usage of a foolish, offensive, or worthless person. Geeking, the verb form, also has a lineage that might surprise us. By 1990, to geek out meant to study hard, a denotation linking the phrase to geek meaning studious diligence. More specifically, the New Hacker’s Dictionary links geeking out to technology, offering the following definition: “Geek out, to temporarily enter techno-nerd mode while in a non-hackish context.”4 But in its 1930s incarnation, the OED defines geeking and geeking out as “to give up, to back down; to lose one’s nerve” (in addition to the meaning of performing as a circus freak). Geeking was originally equated with weakness and failure.

This inversion—from geeking as weakness to geeking as mastery—is worth scrutinizing.5 Even as geeking signifies academic or technical potency, it retains hints of cultural ambivalence. Though geeks may now be celebrated as heroes, they are still characterized in popular culture and the popular press as physically weak, socially maladjusted, and outside of normalcy more often than not. Geeks may or may not differ from nerds. On this distinction, science and technology studies (STS) scholar Ron Eglash quotes novelist Douglas Coupland, who writes that “a geek is a nerd who knows that he is one.”6 In other words, self-awareness and embrace of one’s geeky status are components of geekhood. Geekhood can be borne with pride, whereas nerds are just nerds, dweebs, losers.7 In popular culture, geek can mark outsider status, or outsider status along with studiousness.

To explain this drift over time, we might look to the transition from physical labor to “knowledge work” that has occurred over the twentieth century. As cultural historian Anson Rabinbach explains, throughout the nineteenth century, society was understood to be powered and moved forward by bodies at work: “The human body and the industrial machine were both motors that converted energy into mechanical work.”8 By the late twentieth century, though, the mind was ascendant, at least metaphorically. Industrial and physical work still exist, of course, but they have been rendered invisible by a combination of offshore manufacturing in global supply chains and the discursive exaltation of managerial and intellectual work, which marginalizes service work and manual labor. Geeks have ridden this shift in the opposite direction, moving from a position of weakness and marginality to a position of greater relevance and influence. Human minds, not bodies, are understood to be the seat of power in late capitalism. That said, geeks have not moved into unambiguously hegemonic positions, and the geek body retains its status as a site of spectacle. While geeks no longer decapitate chickens with their teeth, they are often portrayed as gawky, puny, and bespectacled9—perhaps not monstrous, but still deformed.

The genealogy of geek is important for multiple reasons. Not only is it now centered on knowledge (especially arcane knowledge), it has transmuted from a term of insult into a more positive descriptor. Many people using geek to describe themselves and others use it in a fond, self-aware form of teasing and playfulness. As with other iterations of identity politics, geeks have laid claim to a title with a history as a term of disparagement in order to gain power over its use, and they now derive strength from a label that had once been injurious to them. Geeks’ embrace of this term now signifies their own uniqueness, their distinctness from the mainstream and commonality with each other.

Notably, geek’s acquisition of positive valence and in-group signification coincided with computing’s rise in prominence over the past three or four decades. Computers have made a leap in the popular imagination from symbols of dehumanizing bureaucracy to intimate machines for self-expression and liberation.10 Programmers, computing magnates, and hackers have catapulted into the limelight. This is evident in the stature and perceived social power of such figures as Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg. Their technical “wizardry”11 is an object of public reverence. At the same time, especially as geeks shade into hackers, they may be met with suspicion and ambivalence, as Edward Snowden or Julian Assange can attest.12 This indicates that the freakish, threatening elements of geekhood may still be conjured. Programming exhibits a long history of conflict between practitioners and the institutions that employ them, including contestations over requirements for entry and over craft versus science status, as computing historian Nathan Ensmenger has shown.13

Wizardry is also gendered, of course. Technical masculinity precedes computing.14 Historian of communication Susan Douglas locates amateur (ham) operators’ work with radio as a site of reinforcement of ideas about masculine identity and technical competence in the early twentieth century.15 She discusses how the tinkering work performed by men and boys, celebrated in the press, helped attenuate tensions between conflicting definitions of masculinity. Tinkering offered access to a masculine technical domain that was accessible and valued, and that stood in contrast to masculine ideals of ruggedness, strength, and plunder, which were becoming less accessible and less valuable. Douglas’s account demonstrates that radio amateurs seized the new technology and interpreted it in a way that emphasized masculinity and how the technology related to different gender roles; the technology was used to reinterpret masculinity itself. Electronics tinkering was a remarkably stable elite masculine hobby during the twentieth century, offering suburban men and boys both a masculine space within the domesticity of the home and training for white-collar technical professions.16 But by the last decades of the twentieth century, the object of tinkering had begun to shift away from radio and toward computers. The continuity of tinkering as a masculine pursuit offers some clues about geek identity. Computer geeks (like the hams before them) are overwhelmingly likely to be white men (or youth17), often from middle-class or upper-middle-class backgrounds. Reasons for this likely include exposure to computing at a young age; parental educational achievement; gender expectations and socialization of children and youth; and cultural norms in computer science and hobbyist communities, among others.18 Geek identity is one factor perpetuating exclusivity in some technical cultures ranging from engineering schools to Silicon Valley. Yet for all of its exclusivity, it is worth noting that geek identity represents a nonhegemonic form of masculinity:19 geeks may feel persecuted (especially in high school) and geek spaces (online or off) have historically constituted sanctuaries for young men to revel in alternate forms of sociality, leaving oppressive elements of mainstream culture behind.

None of this is to suggest that participation in computing or related technical pursuits is closed to people who are not white men, of course. Strategies to combat the association of geekiness with white masculinity include linking geek identity to technical engagement as opposed to technical virtuosity.20 Technical communities including free and open-source software groups and hackerspaces have repeatedly sought to address issues of diversity within their ranks, as this book demonstrates. Women can and do identify as geeks.21 And Ron Eglash argues that Afrofuturism is an example of an improvised way to achieve technical prowess or identification without being tied to geekiness per se.22 Yet the association of white middle-class masculinity with aptitude and affection for computing is entrenched.

These dynamics may be easier to see in cases considered to be peripheral to hacking (or not considered to be hacking at all). A couple of instances are illustrative. Though leisure activities were a point of entry for whites into technical occupations, by contrast, historian of technology Rayvon Fouché has documented how the meaning of tinkering and inventing for African Americans was circumscribed by racism. Acts of black invention were framed in a negative context; whites declined to celebrate black ingenuity. Fouché quotes a nineteenth-century white lawyer weighing in on a dispute over a black inventor’s patent application: “It is a well-known fact that the horse hay rake was invented by a lazy negro who had a big hay field to rake and didn’t want to do it by hand.”23 In a similar vein, Mexican American lowrider car culture, while occasionally celebrated as an urban folk culture, has historically needed to defend itself against being associated with criminality, and has rarely been portrayed as hacking in a positive, agentic sense.24

Thus, returning to cultural ambivalence toward hackers or hams whose activities might at times be met with suspicion, it is apparent that whiteness has been a resource for white technologists who are understood as nonthreatening, “good” actors in society—more dazzling wizards than criminal threats. Electronics tinkerers who were white could cast even boyish mischief (as practiced by radio hams who trolled the US Navy with obscene messages in the 1910s25) as a stepping stone to cultural legitimacy in the form of high-status technical employment. Needless to say, such behavior would likely be met with harsher social or even legal sanctions for members of social groups whose expressions of dominance (technical or otherwise) would not be celebrated by the wider society.26 Unlike their white counterparts, African Americans exhibiting technical ingenuity might not strive for subversion as much as for legitimacy; some were motivated by the goal of acquiring proper credentials to assimilate into white society.27 Upwardly mobile middle-class whites, on the other hand, did not need to assimilate, and their acts of pranking can be understood as an expression of not only playful engagement with technology but also social dominance.28 It is not necessarily true, though, that either hams or hackers as a class would recognize this consciously.

When black hackers do occur in literature or popular imagination, as they did by the late twentieth century, the signs and signifiers of blackness are largely “used to empower subordinate identities (in this case, hackers) within white society,”29 according to Kali Tal. In other words, while the blackness of these characters bolsters their connotation of subversion vis-à-vis mainstream white society, these representations do not necessarily traffic in actual black lived experience, but appropriate blackness in the service of bolstering the revolutionary or outlaw nature of hacking.30 In a related vein, information studies scholar Lilly Nguyen posits that hacking in present-day Vietnam is best understood as breaking into global technology cultures from which most people in Vietnam have been excluded. This is in spite of the fact that hegemonic hacking is understood to be breaking out of social and technical limitations.31 Nguyen points out that this definition of hacking only applies to hacking that is already integrated into established technical cultures. To understand the practices of Vietnamese hackers requires a shift in understanding of what hacking is.

All of this is to suggest that this book cannot invoke the history of hacking without troubling more traditional accounts that center around computing and electronics, which neglect innovators and appropriators of technology who fall outside the most common scripts.32 This chapter offers an abbreviated history of hacking, open source, and open-technology participation that offers context for the activities described in this book. At the same time, it picks up critiques like Tal’s and Nguyen’s to suggest that present-day diversity advocacy needs to be read as a recentering and redefinition of what counts as hacking—and by extension, who counts as a hacker or technological agent more generally.33

A more conventional genealogy of hacking begins, as noted above, with the activities of obsessed technical enthusiasts in the middle to latter decades of the twentieth century that heralded the rise of computing and particularly networked computing. Phones, trains, and mainframes were important early sites for enthusiasts altering technologies, manipulating them to do things they were not built or expected to do (in the Global North).34 Early networked computing provided a sense of community for its users, and also offered them the sense that this “place” where they convened and communed had its own ethics, politics, and values.35 In parallel, computer programming itself emerged as a recognized skill with application in employment relations. The growth of this professional category witnessed the “[bifurcation] between free software and the programming proletariat,” according to sociologist Tim Jordan. Though both pursuits were based on coding as a practice, different political valences of coding emerged, as practitioners began to distinguish between coding in the service of collectively generated and community-owned projects versus coding for a corporate, for-profit employer or a government employer (in the national interest).36 All the while, Jordan argues, hacking was tied to consistently unequal social relations that not only uncritically adopted the masculinist biases of computing but amplified them, as the transgressive values and practices of hackers could shade into exaggerated misogyny.37 Hacking evolved into a self-conscious and increasingly socially prominent (or notorious) community of practice, which often emphasized breaking into (cracking) other computers on a network for the purposes of exploring and identifying vulnerabilities. Anthropologist Gabriella Coleman offers a rich description of the lifeworld of a budding hacker, arguing that his identity and commitments emerged through intersubjective experience: “Many hackers did not awaken to a consciousness of their ‘hacker nature’ in a moment of joyful epiphany but instead acquired it imperceptibly,” thoroughly immersed in the cultural and technical facets of hacking alongside others engaged in the same activities.38

FLOSS; Hackerspaces and Hacktivism

Simultaneously, free software communities emerged and matured. By the 1990s, free software assemblages could be called a movement, though not necessarily a unified one. STS scholar Christopher Kelty writes, “It was in 1998–99 that geeks came to recognize that they were all doing the same thing and, almost immediately, to argue about why.”39 Free software faced a moment of reckoning with the introduction of the label and similar-yet-different valence of open source. In Kelty’s words:

Free Software forked40 in 1998 when the term Open Source suddenly appeared (a term previously used only by the CIA to refer to unclassified sources of intelligence). The two terms resulted in two separate kinds of narratives: the first, regarding Free Software, stretched back into the 1980s, promoting software freedom and resistance to proprietary software “hoarding,” as Richard Stallman, the head of the Free Software Foundation, refers to it; the second, regarding Open Source, was associated with the dotcom boom and the evangelism of the libertarian pro-business hacker Eric Raymond, who focused on the economic value and cost savings that Open Source Software represented, including the pragmatic (and polymathic) approach that governed the everyday use of Free Software in some of the largest online start-ups (Amazon, Yahoo!, HotWired, and others all “promoted” Free Software by using it to run their shops).41

As this passage illustrates, free software and open source both do and do not refer to the same thing. The practices that define and unify the mode of production to which these labels refer are sharing source code, conceiving of openness, writing licenses, and coordinating collaborations.42 At the present juncture, open source has become a much more ascendant label. (Someone I interviewed for this book in 2012 asked me, not at all unkindly, why I was referring to free software in our interview; for him, this was a settled terminology and free software was anachronistic). In later writing, Kelty wryly notes, “Free software does not exist. This is sad for me, since I wrote a whole book about it.”43 Though some still hold tight to the free software moniker and attendant political values, it is certainly true that the market- and profit-oriented aspects of these practices have become more authoritative and dominant. At the same time, free software is, by definition, always in a state of becoming; it is a potential, not a fixed value.44

A cognate offline phenomenon, with some of the same political ambiguities, is the hackerspace, or hacklab.45 Hackerspaces port the open-source software ethos to the domain of hardware. Their emblem is the 3D printer, which produces tangible objects whose design is endlessly modifiable. In these spaces, like-minded people come together to hack, learn, socialize and experiment.46 They are defined by Wikipedia by their devotion to “computers, technology, science, digital art or electronic art.”47 This sets hackerspaces apart from autonomous spaces that are not centered around technology (though technology has had a prominent role in many visions of alternative community since the Appropriate Technology movement of the 1970s48). That said, such a space—particularly in a European context—may be located in a former squat, and there is a line of continuity between hacklabs, squatted social centers, and community media activist spaces, including pirate radio and independent journalism49 (see figure 2.1). Hackerspaces appeared around the turn of the millennium in Europe, picking up steam after 2005, and reaching North America in approximately 2007, via Germany’s Chaos Computer Club, Europe’s largest association of hackers.50

FIGURE 2.1. A young man peers inside a cabinet-sized radio transmitter, in a warehouse crammed to the rafters with electronics, puppets, and paintings. Visible in this photo in addition to the transmitter are a painted wooden sign that reads “Phoneland” and a PA system for audio. This space is not a hackerspace but a living, art, and social space in an industrial building. It represents a through-line between various kinds of alternative living and technological experiments that precede hackerspaces. Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. Volunteer photo, courtesy of the Prometheus Radio Project.

What hackerspaces do have in common is that they are generally not top-down enterprises.51 They are formed through rhizomatic contact with others in hacking culture, relying on voluntarism for their establishment and maintenance. Most rely on member dues and on financial and in-kind donations to subsist. An especially prominent US hackerspace, Noisebridge in San Francisco, had an operating budget of around $75,000 in 2015, but no staff.52 This would likely be at the upper end of the range for a US hackerspace.53 Similarly, initiatives like voluntaristic efforts to teach women to code might receive small grants from foundations. A couple of events I attended had been underwritten by the Python Software Foundation, which covered the cost of pizza and other refreshments for a series of workshops; these were often held in donated space such as workplaces or universities during off hours. And the organization hosting the unconferences for women in open technology that feature in this book was moving toward a more institutionalized part of the spectrum: it was ramping up to having a couple of paid staff and becoming a tax-exempt nonprofit organization before abruptly shuttering in 2015. Its 990 (exempt organization) tax forms indicate its operating budget was approaching half a million dollars in 2015, including individual and corporate donations. This represents the spectrum of institutionalization of the groups in this book; however, most are relatively small, ad hoc, and informal.

Hackers do not possess a monolithic politics. Gabriella Coleman has referred to them en masse as “politically agnostic.”54 But over time, politically motivated hacking, or hacktivism, has emerged as a significant stream of hacking. This has included civil disobedience in online settings, ranging from electronic mass protest or virtual sit-ins to launching distributed denial-of-service attacks to paralyze corporate websites. It also includes the creation of tools to protect speech and privacy online, and cracking to obtain information on political adversaries.55 It is “not strictly the importation of activist techniques into the digital realm. Rather it is the expression of hacker skills [toward political action].”56

Women in Computing and Hacking

Many activities in this book represent efforts to foreground feminist principles within the wider hacker or hacktivist milieus. They are intended to extend the reach of what practitioners believe is the emancipatory potential of hacking, expanding hacker culture by making it more inclusive.57 While they are a more recent intervention into hacking, there are significant cultural antecedents that predate the period in this book (approximately 2011 to 2016). The history of women in computing is a complex topic that will receive only cursory treatment here. As historians of computing have shown, women were programmers of electronic computers in their earliest days, assisting the Allied wartime efforts in Great Britain and the United States.58 Nonetheless, programming was predominantly associated with masculinity within a decade after the war; women’s work in computing was effaced,59 and over the next few decades men flooded the growing computer-related workforce and established the academic field of computer science.60

In 1991, MIT computer science researcher Ellen Spertus famously asked, “Why are there so few women in computer science?”61 By the first decade of the twenty-first century, women’s rate of participation in academic computer science had declined even further in the United States. US Department of Education statistics indicate that in 1985, a few years before Spertus’s essay, 37 percent of computer science majors were women. In 2009 this number had dropped to 18 percent, and steadily hovered around that percentage during the 2010s at most institutions.62 This situation is obviously in flux: Carnegie Mellon University boasted that 48 percent of incoming first-year students in computer science were women in 2016, an exceptional highwater mark attained through a concerted effort by university administrators, faculty, and students.63 As noted in the introduction of this book, the picture in free software was even more grim: the European Union 2006 policy study64 showed that women’s participation was far less than in academic or commercial computer science, coming in at less than 2 percent. Whether or not the gender disparity between FLOSS and other computing was as large as this report indicated, it acquired significance within free software communities, galvanizing attention to women’s participation in open-source development.

In parallel with the disparity decried by Spertus, 1987 saw the founding of an electronic mailing list to support women in computing, the Systers list. (See chapter 3 for more on this type of communication.) Systers was formed by “a group of female computing professionals” in response to what they perceived as a men-dominated computing culture, to “allow women in computing fields to communicate with each other in a supportive atmosphere.”65 Women on Systers mostly came from the computing sector in industry and university settings. Similarly, The Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing (GHC) was founded in 1994 by computer scientist Anita Borg. Named for a US Navy rear admiral pioneer of programming, it touts itself as the world’s largest gathering of women in computing.66 FLOSS community attention to gender and other diversity issues thus lagged industry and academic attention to these topics by about a decade.

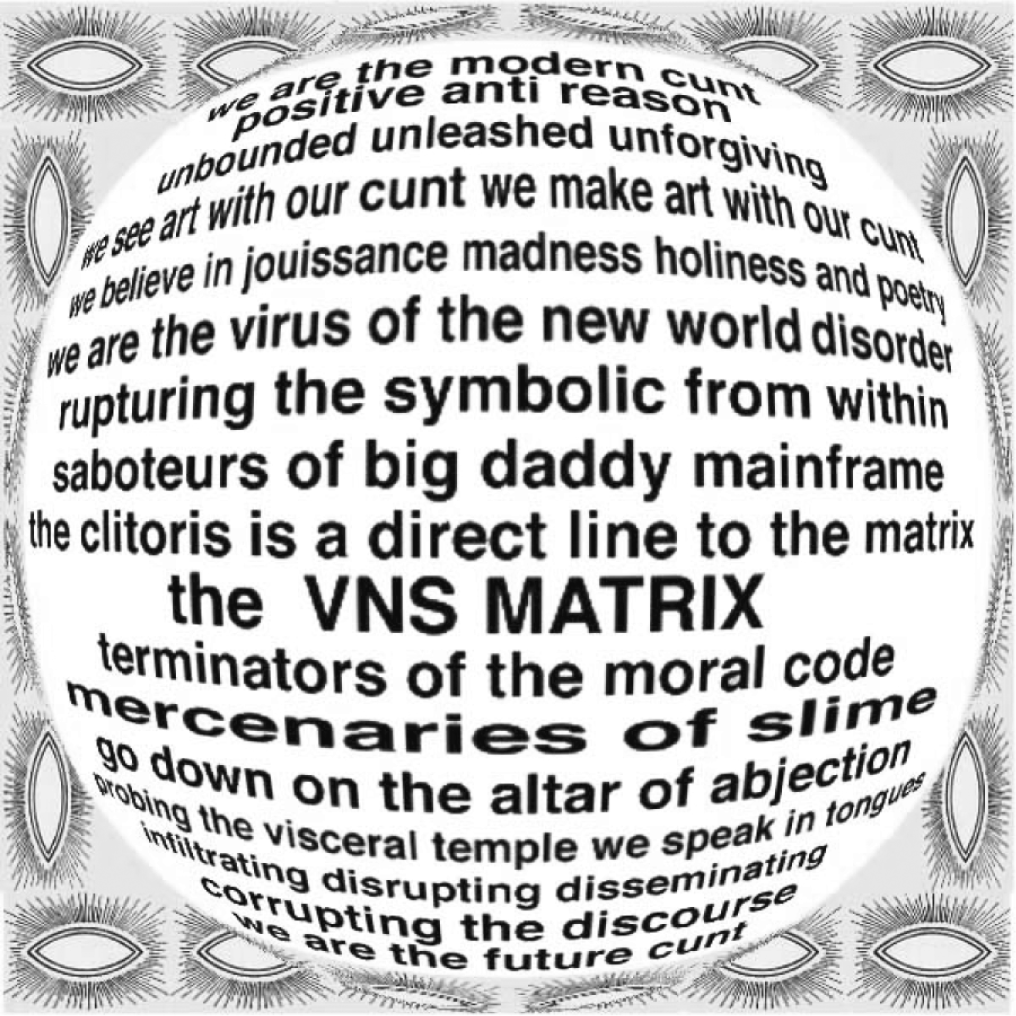

WE CHEW ON THE ROOTS OF CONTROL AND DOMINATION

But there is another thread of women’s participation in computing worth excavating, particularly in the imaginary of who one is when one uses the internet.67 In the early 1990s, cyberfeminists latched onto networked computing as a site of emancipation,68 creating online spaces that were held to contribute to women’s empowerment, participating in identity play, and generally appropriating computing as complementary to, and central to the evolution of, women’s identity and experience (figure 2.2). This stood in contrast to an eco-feminism that drew on tropes of nature and viewed technology with antipathy, associating it with masculine dominance.69 Many cyberfeminist thinkers held that digital technologies would facilitate the blurring of boundaries between humans and machines and between male and female, enabling users to assume alternate identities; new technologies were celebrated for heralding a new relationship between women and machines.70 Imagining de-gendering or reconfiguring gender were powerful and liberating experiences for many who pursued these ideas at the crest of the feminist wave.71 Founders of the 1990s cyberfeminist web portal Mujeres en Red in Spain urged users to participate in free software, linking cyberfeminism to FLOSS.72

FIGURE 2.2. “We are the modern cunt” cyberfeminist manifesto by Australian arts collective VNS Matrix, 1991. See Evans 2014a; 2014b. Courtesy of VNS Matrix.

Of course, the past wasn’t dead, and it wasn’t even past: by early in the next millennium critics and scholars were pointing out that cyberspace was not in fact a space where in-real-life (IRL) social identity got left behind, and that networked computing did not usher in a utopia.73 From our current vantage point, these may be painfully obvious statements. Notable incidents that have occurred in the past few years serve to render them painfully obvious. Possibly the most notorious to date is 2014’s Gamergate, a particularly vicious harassment campaign directed at women gamers, journalists, scholars, and game developers, culminating in death and rape threats.74 More recently, a fracas has surrounded Google engineer James Damore’s 2017 circulation of a memo in which he opined on “natural” gender differences leading to men’s prominence in STEM fields.75 These events could not have occurred without the ascendance of tech employment, both materially and in the cultural imagination, since the two dot-com booms. In other words, a steady drumbeat—sounded by mass media, national governments, college administrators, and countless others—insisting that employment in STEM fields, computing in particular, is the most viable route to secure future employment invites the entrance of new participants. The uptake of open source within major corporate shops has become widespread. These factors have understandably swelled the ranks of related off-the-clock, voluntaristic pursuits. Thus, while little to none of the action in this book is set in workplaces, the communities I have studied are simultaneously distinct from and yet contiguous with wider tech industry culture. In some ways they are standing on the thin edge of a wedge; what is at stake in their contestations in voluntaristic spaces includes their own communities, the workplace, and wider notions of social good.

Arguably, to be a geek is to assume a subject position in a technologically advanced society where an abundance of gear and surfeit of time (whether one’s own leisure time, volunteer labor, time stolen from an employer, or something in between76) can be presumed.77 According to cultural studies scholar Radhika Gajjala, cyberfeminism had a Global North cast, and needed to be adapted to hold promise for those in the Global South; in particular, she questioned whether access to computing could, itself, serve as an equalizing force.78 Not only does geek originate within a largely North American or European cultural context, the export of geek identity can be interpreted as an expression of Global North dominance and a means to bring people in other parts of the world (especially the Global South) into alignment with neoliberal79 and capitalistic values. It is not a coincidence that some of the values of geek communities, including self-organization and peer production, can be easily ported onto discourses of entrepreneurship and bootstrapping.80 Some attempts to export geekhood to “Africans,”81 for example, rightly identify computer capital as a “as a mark of distinction with which to ensure [people’s] viability on the job and in the social structure.”82 Yet these attempts often fail to consider the inadequacy of the distributive paradigm83 as a mode of intervention into systemic inequity. In other words, social power and technical participation are imbricated to such a degree that they may at first glance seem equivalent, but increasing participation in technology is no guarantee of movement into a more empowered social position.

Hacking Hacked?

When technologists seek to advance a technological vision, they are always involved in cultural mediation as much as technological production. In the following chapters, this book will show that diversity advocacy in open technology reveals a complex dialectic between social relations that reinscribe a dominant order and others that begin to challenge, reframe, or rewire this order.84 National and global economic and labor currents are important contexts for understanding diversity advocacy. So, too, is the underarticulated history of hacking in which peripheral people and practices move to the center of the frame. At present, exhortations to “learn to code” are all but deafening. This book shows why the reply, “learn history and social theory!” is not a snarky rejoinder, but an absolutely essential pointer to the means to effectively grasp the economic, technological, and cultural stakes in contestations over diversity in tech fields, and inequality and pluralism more broadly. Everyone becoming a technologist is not a way out; universalist longings cannot unseat sticky dilemmas of inclusion, belonging, and differential social and economic power. A more nuanced understanding, which can be read through present contestations around diversity in technology fields, is urgently needed.

1. Coleman 2012a; Levy 1984.

2. See Slaton 2017.

3. Oxford English Dictionary, “geek, n.” March 2019. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com./view/Entry/77307?rskey=B1Eu4Q&result=1, accessed May 17, 2019.

4. Raymond 1996: 214.

5. See Dunbar-Hester 2016a.

6. Coupland 1996 quoted in Eglash 2002: 61, n1.

7. The OED notes that nerd has also acquired a definition as a person who pursues a “highly technical interest with obsessive or exclusive dedication.” However, it is still more likely to be depreciative, and it is also more broadly defined as “an insignificant, foolish, or socially inept person; a person who is boringly conventional or studious.” Much more could be said here. For example, the appearance of the “black nerd” in popular culture indicates that reclamation of nerd is possible as well. Significantly, this appropriation recodes nerd racially, tying African Americanness to intellectualism. It thus decouples blackness from primitivism, a linkage exemplified in musician Brian Eno’s statement “Do you know what a nerd is? A nerd is a human being without enough Africa in him,” quoted in Eglash 2002: 52.

8. Rabinbach 1992: 2.

9. See, for example, Jain 1999; Pullin 2011 for discussions of how prostheses mark disability.

10. Streeter 2010; Turner 2006.

11. Rosenzweig 1998.

12. Gregg and DiSalvo 2013.

13. Ensmenger 2010a.

14. Though early computer operators were women, historians of computing have shown that many of the skills and practices associated with running the first electronic computers were not associated with a particular gender. In any event, this early history did not unseat the association of technological skill with masculinity (Abbate 2012; Hicks 2017; Light 1999).

16. Douglas 1987; Haring 2006.

17. See Coleman 2012a: 28–30 on youth and coding.

18. Kendall 2002; Margolis and Fisher 2003; Misa 2010. See Ensmenger 2010a on the historically tenuous status of programming and the rise of academic computer science.

19. Some have speculated that geek masculinity got diluted with the appearance of Wall Street and “brogrammer” types in Silicon Valley (Baker 2012), while not unseating masculinity in tech. I will leave it to others to sort out the veracity of these claims; see Rankin 2018, chapter 2 on fraternities and computing in the 1960s.

20. Dunbar-Hester 2008, 2010.

21. Newitz and Anders 2006.

22. Eglash 2002. See also Everett and Wallace 2007; Mavhunga 2014.

23. Fouché 2003: 647 (emphasis Fouché’s). See also de la Peña 2010; Fouché 2006; Green 1995.

24. See Chappell 2001; Henry 2013.

26. In our present day, Arab American or Muslim hackers might be met with extreme suspicion. The 2015 case of Ahmed Mohamed, a Sudanese-American high school student in Texas who built a homemade clock and was accused by his teacher of making a bomb, brought forth charges of ethnic profiling and Islamophobia (Chappell 2015).

27. Fouché 2003: 6.

28. Control over technology has historically been used to enforce social order; technical expertise was constructed in the late nineteenth century in a manner that exerted the power of the “electrical priesthood” over women, rural and lower class people, African Americans, indigenous people, and colonial subjects (Marvin 1988).

29. Tal 2000.

30. And the presence of people like Art McGee, a Bay Area African American “cyber organizer” who maintained Afronet, an electronic bulletin board system (BBS) in the 1990s, is relatively overlooked (McIlwain 2019; see also Bailey 1996).

31. Nguyen 2016 (emphasis in original). See also Beltrán 2018. Gajjala (2014: 289) argues that marginalization itself is reproduced unequally; the “very point of access to the global” can become the point of marginalization for those from non-Western spaces.

32. See Eglash et al. 2004; Nakamura and Chow-White 2011; Tu and Nelson 2001. For historical examinations of race and racialization in computing, see also McIlwain 2019; McPherson 2011; Nakamura 2014; Nelsen 2017. Benjamin (2016) underscores that technoscientific innovation is a site for the making and remaking of race and racism.

33. This argument is contiguous with yet exceeds the myriad stories that are surfacing in popular culture and scholarship about neglected or forgotten contributions by women and people of color in STEM, such as the 2016 commercial film Hidden Figures about four African American women’s contributions to the US space program in the early 1960s. See also Rosner 2018.

34. Jordan 2016: 5.

35. Jordan 2016: 5–6.

36. Jordan 2016: 6.

37. Jordan 2016: 6.

38. Coleman 2012a: 30. I use the masculine pronoun here because Coleman does throughout her chapter; she states, “I use ‘he,’ because most hackers are male” (2012: 25).

39. Kelty 2008: 98.

40. A term in software development that refers to copying code and building it in a new direction, while leaving the original version intact. See chapter 3.

41. Kelty 2008: 99.

42. Kelty 2008: 98.

43. Kelty 2013.

44. Kelty 2013.

45. Hackerspace is roughly interchangeable with hacklab, makerspace, or hackspace, though connotations vary. See Davies 2017a, 2017b; Maxigas 2012; Toupin 2015. Makerspaces in particular may share an ethos of democratized fabrication, but they ultimately boil down to leisure and lifestyle, at quite a remove from more radicalized strands of hacking and hacktivism (see Davies 2017a, 2017b).

46. Toupin 2015.

47. Quoted in Toupin 2015.

48. Dunbar-Hester 2014; Pursell 1993; Turner 2006.

49. Maxigas 2012.

50. Maxigas 2012; Toupin 2015.

51. Here again, a contrast with makerspaces: some are voluntaristically organized, but others have been placed in high schools, and, at the time of this writing, at least five are run by defense contractor Northrop Grumman (chapter 6).

52. Noisebridge, http://

53. Maxigas (2012) states that hackerspaces are more likely to rent, while hacklabs or other spaces in a more explicitly radical tradition are more likely to occupy collectivized or squatted space.

54. Coleman 2012a: 187. Coleman has since chronicled an evolution of hacking politics (2015, 2017).

55. Coleman 2015, 2017; Jordan 2016; see also Renzi 2015.

56. metac0m quoted in Toupin 2015.

57. Toupin 2015.

58. See Abbate 2012; Hicks 2017; Light 1999; Misa 2010.

59. Abbate 2012.

60. See Ensmenger 2010b.

61. Spertus 1991.

62. Raja 2014.

63. Carnegie Mellon University, 2016. It is obviously too early to speculate what effect this will have on graduation rates, workplace composition, etc., and Carnegie Mellon as an elite institution has resources other institutions do not. See also Aspray 2016; Margolis and Fisher 2003.

64. Nafus et al. 2006.

65. Winter and Huff 1996: 32. “Systers” is a play on “sisters” and “sys” as in system administrator.

66. Critics have charged that prominent companies send women workers to the GHC for celebration, while failing to materially support them in workplaces: “Many of the companies in the tech industry who are facing the greatest challenges of gender discrimination are the same ones with a prominent presence at GHC” (Salehi and Tech Workers Coalition 2017).

67. Streeter 2010.

68. “We are a collective body of feminists who … chew on the roots of control and domination,” read an announcement for a feminist hacking event (Email,—to [Feminist Hacking List], June 25, 2018). Though from 2018, this quote harks back to cyberfeminist collectivity and centers power in its technical engagements and explorations. “Root” here also invokes the root directory in an operating system.

69. Haraway 1991a. Haraway’s text is less utopian than many subsequent iterations of these ideas—and cyberfeminism is not a single theory or philosophy.

70. Wajcman 2007: 291.

71. Turkle 1995; see also Stone 1992.

72. Puente 2008: 438.

73. Nakamura 2007.

74. Classicist Mary Beard provocatively argues that since antiquity, women’s voices in the public sphere have often been received with scorn and hostility, unless they are narrowly circumscribed to speak about “women’s issues” (2014). See Chess and Shaw 2015.

75. Lecher 2018. As of this writing, the fired Damore was suing Google, claiming that the company discriminated against conservative white men.

76. Söderberg 2008; Turner 2009.

77. Coleman 2012a; Kelty 2008; Söderberg 2008.

78. Gajjala 1999: 618.

79. Streeter 2010.

80. Streeter 2010: 69–70. See also Lindtner 2015 and forthcoming.

81. Roberts 2012. Beltrán (2018) elaborates on these dynamics in a Latin American context, arguing that hacking reorganizes social relations of precarity and uncertainty.

82. Postigo 2003: 600.

84. Söderberg and Delfanti (2015) write of “hacking hacked” as the dialectic between hacking being recuperated “from below” and the co-optation of (technological) critique by firms and capitalism. See also Ames et al. 2014.