7

Putting Lipstick on a GNU?

REPRESENTATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS

Nowadays, it is claimed that the Chinese and even women are hacking things. Man, am I glad I got to experience “the scene” before it degenerated completely.

—HACKER, 20081

At the 2011 annual conference for the Python programming language (PyCon), held at a conference hotel in downtown Atlanta, GA, I immediately noticed how few women were there. Even though I had been intellectually prepared for a masculine-dominated environment, the experience was a little unnerving. Having hung around tech activism spaces for many years for research, I had become accustomed to being one of only a couple of women in a group of a dozen men. The software conference was a difference of several degrees of magnitude: it wasn’t like joining a soldering meet-up at a squat and being a relative oddity, which might or might not be commented upon. This felt like walking into large, homosocial space like a barracks; I immediately felt that I did not belong, like everyone was looking at me, and I found myself stifling an urge to laugh (which was probably a reaction to how ludicrous I felt in this space and also masking discomfort). I kept a straight face, pulled myself together, and, before long, adjusted enough to revel in my newfound ability to use the bathroom whenever I wanted without making an internal calculus over whether my need to relieve myself was greater than my distaste for standing in line or being late to the next session—an experience I had never had at a conference before or since.

This may seem an idiosyncratic or even frivolous way to mark the oddness of being a woman in the social space that is a men-dominated software conference. But it reveals several key points about this research site. First, it cannot be overstated that as a woman, one cannot enter such a space without standing out. This may be changing. It is not equally true in all sites. In fact, the very next year, when PyCon convened in Santa Clara, CA, the ratio of women to men was still not equal, but more women were present. This was a due to deliberate efforts by organizers.2 It is logical to assume that people exhibiting other visible forms of difference from the dominant social identities in a given site might experience something similar. (For instance, as a white woman,3 I cannot comment directly on the experience of people of color entering white-dominated spaces, but one imagines there are commonalities.) The extraordinary visibility one experiences may or may not create discomfort; this may or may not be overcome over time. Even not presenting in any hyperfeminine way (like many other attendees, I wore jeans and a rumpled button-down shirt), it was certainly hard to walk through a space crowded with men and not feel hypervisible. I did not experience leering, or any other inappropriate behavior, either at official conference sessions or in down time. But it was obvious that the eyes scanning over me—as they do at conferences, searching for friends, or associates one hopes to buttonhole—were taking longer to process my presence or sort me into a category (“not known, not important,” I would guess).

Visible, marked difference may be a source of comment, too. It was difficult to not take ordinary small talk inquiries (all of which were entirely polite and mundane) about who I was or what I was doing at PyCon as specially interrogating my presence, at least somewhat. In a way, being there as a true interloper, a social science professor interested in the dynamics of the community, both broke the ice and gave me cover. I would imagine that being a first-time attendee, a woman, and a programmer could make similar inquiries feel like one’s bona fides or right to be there were under examination, depending on the tone and circumstance. (Women programmers routinely report being assumed to be at software conferences as someone’s girlfriend, or because they are in marketing, not because they have technical roles.4) Being such an obvious outsider, I was received quizzically, but my presence was not challenged. That said, it would have been relatively easy for dynamics to tip in a direction that felt less welcoming, and if that had happened, it would have been hard not to wonder if who I was (or was perceived to be) had something to do with that sort of interaction. It is also possible that affirming that I was not a programmer confirmed subtle biases about women in computing, and made me easier to place—that, ironically, being a total outsider was easier to explain.

All of this is preamble to the main topic of this chapter, which is how—in a climate of burgeoning awareness of diversity issues and advocacy to change the ratios of open-technology participation—community members grappled with issues of social position and identity. I was at the 2011 PyCon precisely because I had identified the Python community as one where diversity advocacy was recently picking up steam; a network of PyLadies or PyStar groups to support women, trans, and nonbinary folks learning Python had begun to form in a variety of cities in 2010–2011. Though most of the technical talks at PyCon (which were, of course, the vast majority) were beyond my ken except at the most conceptual level, there were multiple formal presentations about diversity on the conference program; moreover some more informal “birds of a feather” sessions formed too. I quickly identified a handful of people who seemed like ringleaders for these topics, and attached myself to them. Probably not least because of their reflective awareness of being welcoming as a tenet of diversity work, they were kind, and willing to be ambassadors of PyCon for me.

Background on Social Identities and Technical Cultures

This chapter focuses on how advocates for diversity in open-technology cultures define the identity categories around which they rally. It is evident that they hope to deepen an association between certain categories of social identity and certain forms of technological belonging (as well as challenge other associations). Contemporary social studies of technology treat technology as neither wholly socially determined nor as conforming to or flowing from an internal rational logic. Technologies and technical practices are understood as durable but not immutable assemblages of social relations and technical artifacts. Technology—more specifically, people’s relationships with machines—is an important site of identity construction.5 I conceptualize the people in these voluntaristic open-technology communities not as people who simply work and play with computers and electronics (and crafts), but as people who actively construct identities around their work with these artifacts. They hold a closer relationship to technology than average users.6

The people discussed in this book have encountered and contested long-standing patterns of how technological affinity intersects with social identity and social position. Diversity advocates in open technology are openly struggling with the legacy of computing in North America and Europe as a pursuit that has historically been linked with white men, often from privileged educational and economic backgrounds.7 (Chapter 5 addresses employment relations and social class more directly than the current chapter.) This is partly due to a legacy of technical enthusiasm that formed in the early twentieth century around radio tinkering, which enforced both electronics hobbies and white-collar technical professions as the province of white men.8 Computer programming and hardware tinkering is a later development, but computer enthusiasts represent continuity with earlier forms of technical masculinity, as opposed to a radical new class of people birthed by the introduction of computers. That said, devotion to computing has some distinct traits: the geek stereotype was codified as a concept and a modern vocabulary word around computer enthusiasts.9 Scholars have noted that “in spite of the possibility of emancipation from corporeal realities imagined by early theorists and boosters of new media and cyberspace, bodies and social positions are anything but left behind in relationships with computers … it is still the case within the so-called high tech and new media industries that ‘what kind of work you perform depends on how you are configured biologically and positioned socially.’ ”10 In other words, social context and position, including gender, matter greatly as we consider who participates in technical practices, and who possesses agency with regard to technology, both historically and in the present.

Gender is a relational system for sorting people, which intersects with other systems for social sorting.11 Gender as a category has existed across history, though the particular content of what constitutes, for example, masculinity, femininity, or binary-straining gender formations, has varied over time and across cultures. Gender stands as a useful category for analysis because it is a constitutive element of social relationships based on perceived differences between people of different genders, and it is a primary way of signifying relationships of power.12 Gender identity is not something that is given, it is something that is constantly constructed and remade: “the ‘doer’ is variably constructed in and through the deed,” in the words of Judith Butler.13 Identity is not endlessly fluid merely because it is performative or iterative.14 Rather, identity is constituted through performance, through materiality, through practice, through social relations, through signification and representation. Scholars have shown that “technology [is] both a source and a consequence of gender relations.”15 Gender structure and identity16 are materialized in technological artifacts and practices, and technology is implicated in the production and maintenance of a relational system of gender.17

As Ron Eglash has explored, the whiteness (and masculinity) embedded within geek identity means that members of other racial categories have often had to reject or recast hegemonic geekiness in order to find a comfortable place for themselves within technical subcultures. He specifically discusses Asian American “hipsterism” and Afrofuturism as racially recoded appropriations of technology. In other words, these are nondominant groups’ strategies for extending technological affinity to nonwhites in ways that challenge (but do not totally evade) the hegemonic whiteness of geekdom. (I invoke race and racial categories here under the terms proposed by proponents of critical race theory, who hold that “race and races are products of social thought and relations. Not objective, inherent, or fixed, they correspond to no biological nor genetic reality; rather, races are categories that society invents, manipulates, or retires when convenient.”18) Jessie Daniels calls for greater attention to race and racism in internet studies, arguing that too little attention has been paid to the power dynamics and social structures that have moved racism online (and often transformed it there in new and troubling ways, including globalizing it).19 Quoting Carolyn de la Peña, she argues that racism has “whitened our technological stories,” which are typically unable to reveal the whiteness of not only internet cultures but even the scholarly interrogations of them.20 The present chapter attempts to account for whiteness even in unmarked forms, and to explore how racialized notions of technological participation have led to both named struggle and unidentified blind spots for those who would diversify open-technology cultures.

By definition, identity categories are constructed. One benefit of using identity as a means to understand relationships with technology is how it may help us to get at parts of human experience that are moving targets, slippery, constructed, and yet real.21 Structural factors certainly contribute to individuals’ and groups’ relationships with technology. But here I interrogate identity categories as they are introduced and interpreted by diversity advocates, not because structural factors are unimportant, but because forms of social belonging experienced around relationships with technology are salient for diversity advocates. It goes without saying that there are potential limitations in understanding how race and gender categories become interwoven with technical identities as primarily about identity work; technological cultures are made of (and with) much more than just identity work. (Arguably, though, identity categories feel somewhat more within actors’ control than structural factors.)

Taking the intersection of social identity and experiences with tech as a starting point, this chapter describes how diversity advocates have attempted to grapple with the “who” of diversity advocacy. In other words, which kinds of subjectivities and social identities do advocates believe are missing from tech? How do open-technology communities conceive of the diversity they hope to usher in? What is at stake in these contestations over representation? What is at stake in thinking of this as a matter of representation in the first place? This chapter argues that representation as a goal has limits as a project of empowerment, as noted by scholars of postfeminism and race.22 Representation as a producer or a consumer of a given technology is not necessarily indicative of a change in social power or social status.23 If diversity advocates in open-technology communities are serious about changing how social power is configured, it might serve them well to focus on goals beyond representation in technological participation. While it is easy to conflate technological representation and social power, they are not interchangeable and should not be mistaken for one another.24

Gender, Trouble

Within diversity advocacy writ large (including not only open-technology communities, but industry and government discourses), gender diversity is commonly held as a primary goal. In fact, diversity is frequently used as a metonym for gender diversity, which, in turn, is reducible to more women. In other words, diversity is often almost a shorthand for more women, and women can stand in for diversity, too; each collapses to mean the other. For example, some advocates for diversity claimed that collapsing diversity into women was justified because improving women’s participation was a surefire way to increase other, unmarked forms of diversity overall. For example, at a talk at the 2011 PyCon conference, a speaker said, “Gender diversity can broaden out to other kinds of diversity.”25 Diversity advocates in open-technology communities wrestled with this framing of diversity, sometimes aligning their efforts with it, and at other times challenging it along multiple lines.

As noted multiple times in this book, efforts to promote women’s inclusion in open technology have ramped up in recent years. We have seen the founding of groups like LinuxChix (founded ca. 1998), Debian Women (the Debian operating system project, ca. 2004), Ubuntu Women (2006), the Geek Feminism project (ca. 2008), and, more recently, PyLadies (from the Python computer language community, 2011) proliferate, and the list goes on. One mundane example of this highly self-aware turn toward inclusiveness26 can be seen in the following email exchange. One person (with a masculine username) addressed an electronic mailing list, Womeninfreesoftware, hoping to recruit women to FLOSS projects in which he was involved:

I had a look at the projects I’m directly professionally involved in—[project A] and [project B]. And, well, they’re pretty much your typical FLOSS sausage fests [men-dominated spaces], I’m afraid. We do actually have a few women involved, but they’re all [company] employees [who are paid to be there]; on the volunteer side, it’s all men so far.

So I’m hoping to encourage people—women in particular—reading this list to come and get involved with [project A] and [project B].27

This quote exemplifies a project participant reaching out to women and in so doing, demonstrating that these projects were aware of diversity issues and making an effort to be welcoming. Another list subscriber replied, “Thanks, [Name], for taking the time to make that bid for participants in your project. It was exactly what the world actually needs[,] much more so than almost any other single action.”28 These quotes illustrate the typical, mundane framing of gender diversity as inclusion of women in free software projects (all post-2006 initiatives should be read in part as a reaction to the 2006 EU policy report by Nafus et al. showing a minuscule rate of participation by women). Reaching out to women was seen as a straightforward, and appreciated, way to foster the inclusion that diversity advocates prized.

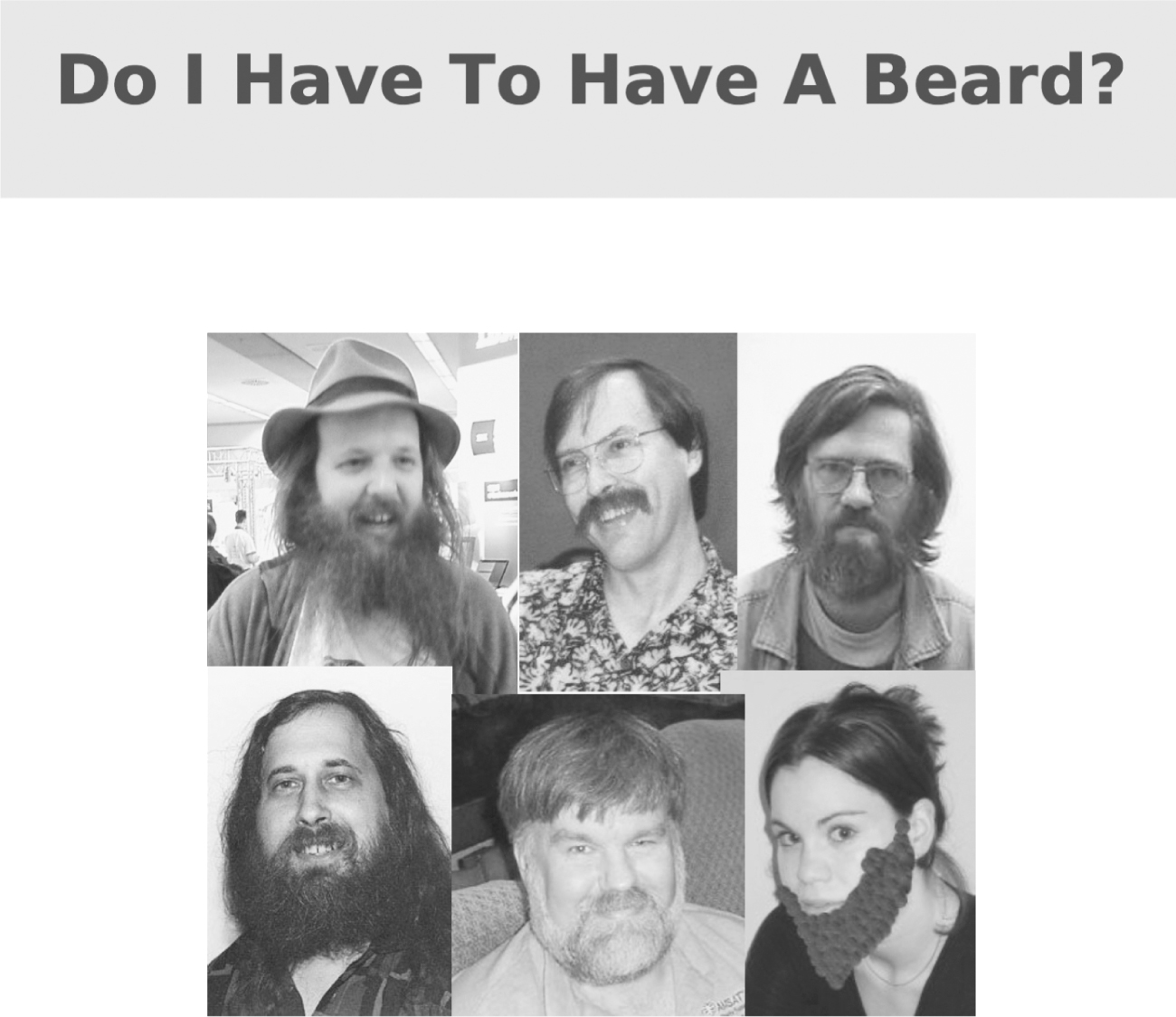

A major concern of diversity advocates, which runs throughout this book, was how to rethink the gender codes surrounding hacking, coding, and computing. In particular, advocates wished to challenge tacit or explicit associations of masculinity with coding and hacking, which they believed could begin to undo the “sausage fest” climate of open-technology projects. This was a constant refrain. It is so ubiquitous that outside of this chapter I rarely comment in depth on the embedded assumptions about gender that diversity advocates were sometimes exposing in order to challenge, and sometimes recapitulating. But here they are of central concern. It is worth considering in detail some of the wide-ranging claims that constitute how diversity advocates were framing and responding to these issues.

Why did open-technology practitioners identify advocacy around gender and participation as a primary site of intervention? How did they understand the lifeworld of open technology, and in what ways did they feel it needed to be changed? One example of the lifeworld of open technology that advocates hoped to dispute can be seen in the following quote. During the dispute in the Philadelphia hackerspace about whether to host an event featuring sex toy hacking (chapter 3), one member wrote the following statement as he expressed his reluctance to host the event:

A lot of the hackers here at the space are the Make Magazine/Instructables type, not the Julian Assange HOPE-conference attending type, or even the kind that cares much about a global movement of hackerspaces. I’m not sure what category dildo hacking falls in.… For a lot of people, DIY has to do with a sort of Father-son nostalgia for Popular Science magazine, model airplanes, and so on, so even if we don’t actually get too many kids in the door there is a lot to be said for promoting that image.29

This comment is quite illuminating. The hackerspace member allows for a range of hacking practices, first invoking an independent producer ideal, exemplified in Make magazine (though Maker Faire and much of DIY actually reproduces consumer culture30). He next refers to a more politicized, Wikileaks-esque, information-wants-to-be-free sort of hacker.31 Then, he correctly signals the heritage of DIY as a way to impart technical affinity to boys. Notably, while he allows for different motivations for hacking, they are all tied to masculinity, which is marked, and whiteness, which is not. In other words, part of what diversity advocates struggled to address was that even as hacking itself might be malleable enough to encompass a range of politics and practices, the default hacker was under all of these scenarios a man or a boy.32

This association between hacking technologies and masculinity was thus a prime site for advocates to intervene. Over and over, advocates discussed what they perceived as a tacit, entrenched embrace of masculine identity performance in the practices of collaboration around software and hardware. Many early studies of computer geeks have argued that one of the affective pleasures people find in computing is mastery. Writing in 1996, Sherry Turkle observed that “[Hackers] are passionately involved in mastery of the machine itself.”33 (This passion differentiated highly skilled and enthusiastic user groups like hackers from ordinary users who were interested in running applications, but not necessarily trying to get inside the machines’ code or hardware themselves.) This is consonant with the construction of masculinity around control over technologies that preceded computing.34 In computing, the exaltation of mastery occurred in part through competitive dynamics, often evinced in fleeting moments of interaction, but in aggregate constituting a cultural norm (to which many computer enthusiasts were exposed quite early in life35). Socialization practices reflect these norms: old-timers in particular often recalled being hazed while learning to program. Even when one is not being hazed per se, there are decades-old geek norms to “read the fucking manual” (RTFM) before asking questions, which discourages people from displaying uncertainty. Joseph Reagle writes that the RTFM norm can provide a positive incentive toward self-cultivation: one will be valued if one strives “to learn [to code], to write a useful utility, and [then] to share [one’s] learning and its fruits with others.”36 Less positively, of course, this directive to independently cultivate and exhibit mastery can also be used to intimidate, to shame, and to turn off newcomers who are for whatever reason unwilling or unable to flourish under these conditions. This effect has been celebrated in mainstream open source. Eric Raymond, open-source evangelist and author of the famed essay “The Cathedral and the Bazaar” writes,

We’re (largely) volunteers. We take time out of busy lives to answer questions, and at times we’re overwhelmed with them. So we filter ruthlessly. In particular, we throw away questions from people who appear to be losers in order to spend our question-answering time more efficiently, on winners. If you find this attitude obnoxious, condescending, or arrogant, check your assumptions. We’re not asking you to genuflect to us—in fact, most of us would love nothing more than to deal with you as an equal. But it’s simply not efficient for us to try to help people who are not willing to help themselves.37

This ethos has also been subject to pushback; Reagle notes that Wikipedia reminds its community members to “not bite the newcomers.”38 Nonetheless, these dynamics are well documented as long-standing tenets of computing culture and especially open source, and it is not necessary to rehearse them here beyond a basic adumbration.

These dynamics conform to a normative masculinity, where competitive displays and mastery are understood as virtues. Scholars have argued that geek masculinity is in some ways distinct from hegemonic masculinity,39 but it still trades in “othering” women.40 David Bell writes, “Geek masculinity [is] a complex negotiation of outsiderhood and privilege, even outsiderhood as privilege, which sometimes suggests possibilities for gender inclusivity, but at other times reinstates rigid gender boundaries and hierarchies.”41 It is worth noting that masculinity is a set of (contingent and historically malleable) characteristics that have been laden with the power to signify men and maleness, but do not necessarily inhere to men. Nor is it the case that women (or nonbinary folks) may not possess or exhibit traits that are gendered masculine. Rather, signifiers of masculinity and femininity are components of a symbolic repertoire that support a cultural system of gender.

Contesting Gender Essentialism

With this as introduction, how have diversity advocates dealt with normative masculinity as a component of open-technology cultures? The answer to this question is not straightforward, and it illustrates many pitfalls for advocates. One major stumbling point, which seemed all but impossible to resolve, was how to challenge normative masculinity as a cultural default without invoking normative femininity as its opposite. This played out in a variety of ways.

On the list where the person had lamented the “sausage fests” in his current open-source projects, list members discussed making a logo to represent the list itself. One list subscriber proposed, “If we took the picture of a GNU used by FSF [Free Software Foundation] … added lipstick, eye shadow, and mascara, replace the beard by a string of pearls, and replaced the horns by a feminine hat, with a flower sticking up from the hat, I think that would convey the idea.”42 The “GNU symbol” is the logo of a Unix-like, Linux-related operating system, a line drawing of the antelope-like gnu, replete with beard and horns as described in the email (figure 7.1). In other words, the subscriber proposed adorning the GNU gnu with normative markers of femininity.

FIGURE 7.1. GNU logo, GNU Project, ca. 2009. Used with permission under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 License.

Responses to this suggestion registered immediate discomfort. One person commented, “I … am not a big fan of this idea. Most women in free software do not adhere to traditionally feminine styles of dress/grooming—I have seen very few wearing makeup let alone pearls at free software events—and I think this sort of appearance would be alienating to many of us.”43 The original poster agreed with this (“You’re right.… Most of us don’t dress over-the-top feminine. I certainly don’t.”44) and added that the original suggestion was intended to be a humorous way of depicting women in FLOSS. Posters to the list struggled with how to signal the presence of women without falling back on representations of normative femininity that many of them found “alienating.” They also touched on race, as one commenter wrote, “I think the gnu is more appealing than the wasp-y [white Anglo-Saxon protestant] noses and dainty lips [in some other ideas for a logo].”45

Along similar lines, in a question and answer session following a presentation called “Diversity in Tech: Improving Our Toolset” at the 2011 PyCon meeting, normative assumptions about femininity caused significant controversy. The presenter, a thirty-something white woman who worked as a software engineer in a large Silicon Valley firm, offered an overview of research that addressed “diversity in the workforce.” Beginning with a description of “gender diversity” (meaning women) in the tech industry, the presenter said there were things that made women more or less likely to participate in tech fields. She described a hypothetical example where a woman approached a recruiting manager, who was a man, about an engineering job, and was met with a brief moment of disbelief that she was the applicant (because of her gender). The presenter claimed that research showed that expectations have an effect on performance, suggesting that the woman engineer might be undermined by the manager’s expectations: “The engineering manager’s expectations would have impacted how he judged her, and could conceivably have impacted how she performed in a job if she had taken that job.”46 She pointed out that there was “no malice on the part of the engineering manager,” but “if you’re not watching what you’re doing, you can actually materially damage the ability of other people to succeed alongside you.”47 She then told the audience that “working in a diverse workforce is hard. It’s harder than working with people like you.… You will be more likely to face people challenging you.” In the end, though, she claimed that any potential strife had a payoff: “Conflict and challenge [are] how we arrive at interesting, creative solutions to problems.”48 Her concluding point was that, “Diversity is hard, but if you work hard at it, you can end up ultimately with a much better situation.”49

On the one hand, this presentation was utterly banal. It signaled the importance of diversity, invoked social science research, and argued that embracing diversity was, while somewhat challenging, likely to yield benefit to firms and workers (and implicitly to consumers). This line of argument is eminently familiar from many corporate, higher education, and government discourses about diversity. It was certainly presented as something no reasonable person could disagree with. And yet somehow, it was apparent that the presentation had caused the temperature of the room to rise. There were a few possibilities as to why. First, the presentation had, knowingly or not, the tone of a human resources–driven (and mandatory) workplace training session, on which some attendees later commented disparagingly.50 While it did not address topics like harassment, the tone was fairly dour. It occurred to me that given that the audience members were all there voluntarily (this was not a plenary session, so they could have attended several other concurrent talks instead), many of them possibly were not there for a stern lecture making the point that diversity is a virtue. Diversity advocacy can be a volatile topic in the “sausage fest” environment of computing and has been interpreted as a threat to the “clubhouse” atmosphere of programming workplaces and (especially) FLOSS projects. This presentation probably did little to enhance the notion that that diversity work was anything other than a slog, or that diversity conferred benefits that intersected with the affective dimensions of computing prized by many. (This stood in contrast to another presentation earlier that day, given by advocates for diversity in open source whose focus was more on voluntaristic projects. Entitled “Getting More Contributors (and Diversity) through Outreach,” advocates there emphasized finding out why people were involved and whether they were having fun.51)

The “Improving our Toolset” presentation became volatile during the Q&A following it, along lines that are perhaps surprising. Audience members had lined up to ask the speaker questions that presented scenarios they had encountered and asked what could have been done differently. One fellow, a white man in his thirties or forties, began his question by remarking that he had been married recently. He said that his wife had some talents that included “communicating, worrying, and correcting my grammar and spelling mistakes.”52 He said the presentation had caused him to think about how if men and women were “fifty-fifty” in programming, coding might be better documented and contain more “case statements.” (These are conditional control structures in programming that allow for a selection to be made depending on whether a clause directs one choice or another; in rough terms, analogous to “if this, then that,” or especially, “if this, and this, then that.” In other words, he was referring to thinking about outcomes resulting from multiple layers of contingency, perhaps born of a cautious mindset; in his words, “is this gonna happen, is this gonna happen, is that gonna happen.”) He mused that teams might be stronger if they were composed of people with complementary skills, which he saw as correlated with gender. At this point, an audience member, a white man in his thirties from Minneapolis who was also in line to ask a question, had an outburst, shouting, “COME ON, MAN!! Are you serious?!??” and stormed out of the session. The speaker gingerly replied, asking if the querent was suggesting that “code would be better documented, and would it cover cases that might go wrong” if his wife were a programmer. She said she had not seen research that indicated that this was true, and then added diplomatically, “I find that it’s good to be really careful about making gender assumptions.”53 The Q&A then turned toward some of the issues that this question had raised. The next person to speak, a white woman with a northern European accent, challenged the previous querent. She pounced on the suggestion that inherent gender differences guided people in different domains of action, and said, “stereotypes don’t help, even if they’re complimentary,” at which point many people spontaneously applauded. She also said, “What about women in politics? People think it would be so much better if the world were run by women, there would be no more wars—but ever hear of Margaret Thatcher? … When you generalize, even if it’s well-meaning … [I would say] thanks for the compliment, but no thanks.”54 As the original querent reacted to the presentation and attempted to map its topics to his own observations, he invoked gender stereotypes of women as caring, cautious, and communicative (which were, he averred, different from his own approach, an implicitly masculine one). He was no doubt surprised by the reaction to his question, which, it seemed, was sincere, and was not in any way overtly denigrating toward women. But immediately, both the presenter and two other audience members resisted this essentialism—more and less forcefully.

Though the fellow asking the question that invoked his wife was undoubtedly taken aback by these reactions, diversity advocates were primed to be impatient. Certainly, wife, mother, and other roles gendered feminine are often used as shorthand for nontechnical people;55 language habits have been a way of entrenching the notion that women are outsiders in computing. Second, though, this fellow’s question and the ensuing discussion illustrated that to advocate for women in open technology is to have ideas about who women are and why their presence is a good thing. Provisionally agreeing on diversity (or more women) as a virtue is, of course, not the same as forming consensus about these matters. These are thorny issues, rife with identity politics, issues of representation, and, as seen here, questions of essentialism. In the case of people even casually steeped in gender studies, which includes no small number of people in open-technology communities, to promote women in technology was to fairly immediately run afoul of gender stereotypes. The fellow who asked the question invoking his wife was either not familiar with or in disagreement with common critiques of gender essentialism. His misunderstanding of the issues elicited impatience in part because while advocates tended to agree that essentialism was a problem, how to combat it was far from clear, both among advocates themselves and when they were facing wider open-technology communities. And advocates did not necessarily produce any converts to their way of thinking in this interaction.

Later, in an impromptu discussion about the presentation, people criticized the presenter for turning off audience members. They said she had struck the wrong tone for the developers and community managers who were there, most of whom were not hiring managers, and who were probably already “on the train,” accepting of diversity as a good, at least in the abstract, and not in need of that kind of “remedial information.”56 They did not, however, address how the explosion over gender stereotyping might have puzzled or alienated people who were less conversant in critiques of gender essentialism.

FIGURE 7.2. Session proposal, “Does talking about differences …,” Washington, DC, July 2012. Photograph by the author.

But more sympathetically, taking the measure of the GNU and PyCon examples, it becomes evident that arguing for gender diversity without promoting gender essentialism was a dilemma for diversity advocates. Advocates themselves acknowledged this in many ways. At an unconference devoted to “women* in open technology,” one person proposed a conference session to talk about this double bind: how to promote women in open technology without reducing people to stereotypes. She expressed this on a note, taped to a wall where people posted various ideas for sessions (figure 7.2):

Her session topic centered on a question, “Does talking about differences between men and women reinforce them?” The simple phrasing of the question belies a tangled thicket of issues that social scientists and theorists of gender in culture have not resolved; there is certainly even less consensus about these topics in the wider society. She was wary of stereotyping members of masculine and feminine genders, especially allowing a focus on gender difference to amplify perceptions of difference and thus potentially to actually construct or deepen difference. The question is almost poignant, in that one can sense both her hope for moving past divisions and her fear of entrenching them.

Later that day, Miriam, a woman who had for years worked and volunteered in technology communities, offered thoughtful comments. She said:

The problem is not that men are in workplaces [and therefore that] more women will make workplaces better. The problem is masculine behavior. Women [too] can emulate that, act competitive. And then that makes it even worse, [people will] comment on them as [being] “catty” and [that behavior will] be used to generalize about women.57

This comment raises many issues worthy of scrutiny. It presents the belief that gender differences are not inherent; if women can act “masculine” and competitive, it stands to reason that men can act in less stereotypically masculine ways as well. She rightly notes that technical cultures are often competitive and links this to masculinity, but does not think that “just adding women” will necessarily change the cultural norms.58 Further, she worries that placing women in environments where masculine norms hold sway will set them up for failure; even if they succeed in aping in those patterns of behavior, they may then be penalized for not being appropriately feminine: competitiveness, a virtue in men, in a woman is perceived as cattiness, a vice. At a subsequent meeting of the same unconference, conversation was devoted to what one person called the “likeability paradox”: she said that for women being liked and being perceived as competent were inversely correlated, especially in men-dominated fields.59 She said that this meant that “women have to choose between being liked and being powerful.” Social science research suggests that there is truth to this claim, and that at the very least this terrain is much more challenging for women.60 And in an interview, another woman said that in an earlier period in her career, “I had worked hard to emulate assholes.”61 In other words, in domains where competence was strongly coupled with technical masculinity (performed through competitive displays centering on technical knowledge), placing technically competent women in this environment would not necessarily make the environment “less masculine,” nor see the women rewarded for their competence.

All of this is to say that there was a high degree of reflectiveness about gender and a strong current of questioning essentialist tropes among these advocates for diversity. Even when engaging in conversations about differences between men and women, people usually tried to stake out territory that allowed for differences among members of a given gender. One person expressed this when she said at an unconference meeting, “When people say ‘women [have this in common; are this way],’ it should not mean ‘all women are [this way; have this in common].”62 They also routinely allowed for the possibility of common characteristics in people of different genders. The above advocate’s position that “adding women” was a less satisfactory solution to gender trouble in technical communities than titrating out some of the communities’ masculinity was echoed in different ways. Though subtle, this is a notable distinction. Especially in environments that were critically oriented toward gender, which many of these were, people did not view femininity as a polar opposite to masculinity, and they also did not believe that all women were necessarily especially feminine.

Not uncommonly, people suggested imbuing environments with subtle cues that subjected the alpha geek competitive masculinity common in open-technology communities to subversion or redirection. One person said that in her workplace, new staff, regardless of gender, were given colorful arm-warmers and a brightly-colored toy.63 Another person suggested that it might be beneficial for members (of all genders) of her hackerspace to all go out and “get their nails painted with the hackerspace’s colors.”64 One person in an interview said that she had seen people use glitter at events to lighten them up; she claimed that in places where an all-black hacker aesthetic was dominant, festooning people with glitter was a way to inject a feeling of “color and celebration and comfortable vibes.”65 Notably, no one here was suggesting that glitter, colored armbands, or hackerspace-themed nail polish would feminize masculine spaces, nor was this their goal. In fact, these interventions can be read as resistance to the likes of “pink technology,” a marketing strategy to promote girl-oriented consumer electronics, as described by Mary Celeste Kearny.66 Rather, they were intended to queer or attenuate normative masculinity: the toy and the arm-warmers in bright primary colors reference childhood as much as anything else, and glitter and group nail polish evoke carnival or drag. (Another person described a community of coders who focused on both technical development and maintaining an inclusive environment: “[they] sport a lot of rainbows and glitter in a kind of supercampy anti-machismo.”67) It is perhaps debatable whether other people outside of these subcultures—or even everyone within them—would read these signifiers the same way. Nonetheless, it is apparent that for these actors, these strategies represent attempts to decenter masculinity without replacing it with normative femininity, of which they were critical and with which many of them were uncomfortable (as mentioned in the “lipstick on the GNU” discussion above).

Genderfuck: Queer, Nonconforming, Otherwise

This becomes especially apparent when we consider other aspects of gender that were swirling around in this milieu. In the discussion about the GNU, list members also identified another issue. One person commented, “I think the question of gender identity goes deeper than ‘do we all wear pearls here at [Womeninfreesoftware]’ to, are we really limiting our reach to ‘women’ or is there also room for gender queer techies who don’t identify with the gender binary?”68 In other words, using normatively feminine markers of identity to represent women in FLOSS was problematic for two reasons. First, these markers invoked and threatened to reinscribe a version of femininity that many geek women did not relate to, as discussed above. Second, they undermined a commitment to gender diversity salient in open-technology circles, where the prevalence of nonbinary- and trans-identified people seems relatively high (or is, at least, visible and vocal). In other words, for many, gender diversity did not stop with “more women.” Many projects and hackerspaces with a commitment to gender inclusion explicitly address and include people who identify as genderqueer, nonbinary, and so on. One representative example is from a feminist hackerspace, which describes its community as “intersectional feminists, women-centered, and queer and trans-inclusive.”69

There is a likely prehistory here, which I can only suggest. Preceding the fairly recent bursting of trans presence into the cultural mainstream, trans, genderqueer, and nonbinary gender identity in many tech circles was already somewhat established. There are a variety of factors at play, certainly, but one stands out as worthy of sustained consideration. Whether or not people are self-aware about this connection, there seems to be some correlation between people who are drawn to hacking and tinkering and people who are drawn to questioning gender as a system. Many people make this connection self-consciously, as did Salix, a queer-identified, twenty-something person who had cofounded a makerspace in the Pacific Northwest, who said,

Why are there so many queer geeks? To me the word “hacker” is about anyone who wants to tear down a system. It’s the same with [my] gender and sexuality—tearing down a system and seeing where I fit in it. I wonder if it’s something in brain chemistry [where people are “wired” to be attracted to tech and to question gender]. [Hackers] also have the experience of construction of self online. You play with construction of self, you play with sexuality.…

Through the technology we’re building now, we are expressing ourselves … [there are opportunities] to finally get into the nuances of your personality … we are seeing [new ways for] how people express themselves.70

Playing with selfhood online is a behavior that commentators made much of in the early days of the internet, particularly emphasizing the liberating potential of this realm of interaction.71 Though more recent scholarship has provided a welcome corrective to the notion that social categories like race, gender, and class get left behind in online spaces, and to the suggestion that there is a stark separation between online and IRL, it is also true that people like Salix have often spent time during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood playing online games or interacting in spaces like chatrooms or IRC.72 And they found these to be spaces for reflection about gender and sexuality, taking away the lesson that technology could be used to enhance or express true selfhood. (Salix is also an enthusiast of transhumanism, which informs a techno-utopian belief that technology can get into and enhance nuances of one’s personality or body, or provide new avenues for self-expression.73)

Salix is hardly alone in identifying an association between hacking objects or code and hacking gender. A queer-identified Belgian artist in their late thirties said in a meeting, “If you’re trying to open the source code of gender, it’s not right to use a closed-source operating system.… If you’re reflecting on your gender, you will be similarly reflective about technology.”74 They suggested that for a person drawn to question their gender (and heteronormative sexuality), there is “an issue [when] the first hardware you encounter is closed, is a [Microsoft] Windows system.” This shows a direct analogy in their thinking between an open-source ethos in computing and a questioning attitude toward gender; to wish to see inside and modify where one fit in a socially assigned system of gender was not very different from wanting to see inside and modify the operating system of one’s computer. They also suggest that people might experience questioning and exploration from the earliest points of contact with these systems: something could feel intuitively wrong about learning to compute on a “closed” machine like a PC running Windows. The artist and the hackerspace founder above were incredibly self-aware and articulate about the parallels for them between hacking gender and hacking machines.

Similarly, in the first-person account of a trans woman in London named Sarah Constantine, a connection arises between electronics hacking and being trans:

[As a boy growing up] I’d try to drag bits of machinery home. Old televisions, radios, mopeds, motorbikes, lawnmowers, anything electrical, mechanical, a boiler.… At twenty-four, I got into electronics. This is in the early to mid-Eighties. I spent three years building a huge sixty-five module synthesizer.… I would go to sleep thinking about electronics and engineering and wake up thinking about electronics and working out circuits.…

[Living in my assigned masculine gender,] I had created a [convincing] male persona.… [I] was a chameleon. But you’re constantly paranoid that you’re going to be found out.…

I just started taking hormones out of curiosity to see what it did to me.… When I transitioned, one of the things I found out was that about 80 percent of male-to-female [trans people] have a background in electronics and engineering.

I’m not kidding. It’s so freaky. One day at the psychiatrist’s—you have to see a psychiatrist for two years [to be permitted to transition medically]—there was a notice on the board in the waiting room. A self-help group had started up in someone’s living room. So I went around. There are about eight sheepish-looking, ropy-looking [trans people]. And we’re all sitting there in someone’s living room. Things were a bit awkward. We didn’t know what to talk about. Someone mentioned in passing they were into electronics. I said I was into electronics. Someone said, “I started [reading] this Ladybird book [a UK children’s book series including educational titles]. It was called Build Your Own Transistor Radio with a Plank of Wood.” I said, “I remember that book. Use the OC71 transistor.” Someone else said, “Oh yes, and the OC45 for the radio frequency.” I mentioned modular synths and someone said, “What chip did you use for your roger-controlled oscillator?”

“I used the Ellum 13 700.”

“That’s the preceding?”

“That’s right, because it had linearizing diodes in the input and non-dedicated diodes.”

“That’s right. It came with an 11 fuel pin.”

All of a sudden it’s like … [hums the theme from The Twilight Zone] [television program]. What’s happening? They all know the same code numbers I do? I looked at them, they were all looking back, and I realized they’re all really nerdy.75

This is one person’s account, and as such it must be regarded as anecdotal data (the “80 percent” she references is clearly hyperbolic). But it is highly suggestive, and it conforms to how others have characterized relationships with technologies as sites where gender identities may be transformed.76 The high degree of interest in and pleasure from electronics’ inner workings that Constantine describes is consistent with many geeks’ accounts and is what sets them apart from “everyday” users of the same technologies. Her lengthy description of her own solace in electronics and the discovery that her pursuit was not singular to her stand out in her narrative. Building modular synthesizers, tinkering with ham radio transmitters or computer hardware, and coding are all practices that reflect obsessive enthusiasm for playing with and reconfiguring these machines. To reconfigure one’s own gender is, for some, a logical next step for someone accustomed to “hacking on” machines and dissatisfied with or questioning their assigned gender. Constantine, the Belgian artist, and the Northwest makerspace founder each describe this, albeit in slightly different ways. Constantine describes the concrete step of “taking hormones because I was curious,” while Salix describes a more abstract “questioning [of] a system and where I fit in it,” wondering (half-jokingly) if this connection can be explained by “brain chemistry.”77 (Though I in no way wish to wade into debates about a biological basis for gender, in the brain or otherwise, Salix and Constantine might find much to discuss.) The Belgian artist draws a parallel between modifying the source code of a machine and being reflective about the source code of gender (and vice versa).

However evanescent some of these connections may be, there is evidence that in many tech subcultures, a high level of attention is paid to gender issues. These very much include nonbinary conceptions of gender, and people are often quite self-aware about gender issues. In the unconferences for “women in open technology,” organizers had explicitly required that applicants for the events “identify as women in some way that was significant to them,” leaving to applicants to determine how feminine gender applied to them. This left a good deal of room for gender presentations and identities across a spectrum, and as discussed above, much of geek femininity already traffics in nonnormative femininities. In the unconferences, these topics were discussed at length. One person who said they identified as “genderfuck” or gender-fluid also said that they were aware that “I have more street cred if I say I am a woman fighting the gender gap [in tech] than if I say I’m a gender-fluid person fighting the gender gap [so as a matter of strategy I will say I’m a woman].”78 Sam, a queer-identified person, said, “Being in tech has changed how I identify. I didn’t really care [before] but now I’m like, ‘I’m a woman! Women matter! We need more women!’ But if I need to throw in the word ‘trans’ because I think the room needs to hear that, I’ll throw in the word ‘trans’ too because I can do that [identify that way as well].”79 Jamie, a nonbinary queer-identified person with a very androgynous presentation, said they “felt comfortable advocating for women even if I feel [I am] particularly masculine”80 and also said that women-only spaces were not especially comfortable, because “[I have felt] more ostracized in lesbian-only spaces.”81 Tech, as a normatively masculine domain, may seem to offer a home for people who do not identify as particularly feminine, but it is certainly not without complications.

For anyone who does not immediately feel like they fit into the normative masculinity of tech culture, reflection on gender issues is all but compulsory. Women (to say nothing of people who are genderqueer, etc.) are always needing to negotiate their identities and their presence in these communities, often feeling subtly policed in a damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don’t way. One person said that tech itself “deprecates putting any effort into your appearance. I go back and forth. No exercise, fuck taking care of my appearance, fuck makeup, fuck plucking my eyebrows.… But then, [I feel like,] no, I want to take care of my appearance, because I feel good when I do this.”82 This echoes the geek stereotype of an obsessive person neglecting bodily care routines in order to hack or tinker: computer-obsessed MIT students in the 1980s were described as people who “flaunt their pimples, their pasty complexions, their knobby knees, their thin, under-developed bodies.”83 One woman agreed: “I’m not hyperfeminine normally, but when I’m in a hypermasculine environment, I want to be like, dude! I’m a woman. I’m not sure if this [constant self-consciousness] affects my authentic [experience of] self.”84 To this, another woman replied, “I get a comment if I wear a skirt or pants. It underscores that I’m being watched.”85 All these comments make evident that there is no neutral or default way for women* to present in tech workplaces or hobbyist spaces (which clarifies the appeal of separate spaces, as discussed in chapter 4). As I found entering the 2011 PyCon, eyes will be on you if you present in a way that deviates from the expected masculine presentation; even though this may not feel like hostile attention, it can be palpable.

Jamie (the self-described “masculine” nonbinary person, who had been assigned female at birth) expressed a poignant example of women’s experiences in technical space, remarking, “I need to check my own assumptions. If I see someone [presenting in a way that is normatively] feminine, I do [initially] assume they are in marketing or HR. I don’t [then] think, I’m a bad person, I [just] think [that] I absorbed some bad messages.”86 In other words, even someone like Jamie who consciously “knew better”—having been assigned feminine gender at birth, experienced technical socialization as a person who did not feel they fit into the gender binary, and gone through engineering studies at MIT—still ran up against internalized stereotypes, making knee-jerk assumptions that women were ill-suited for technical roles. In turn, women, wherever on a spectrum of gender they identify, are confronted with needing to position themselves vis-à-vis these perceptions and biases. (This can also be seen in the above discussion of women needing to choose between being perceived as likeable or competent.)

One strategy people adopted was to have a shock of vibrantly colored hair. I came to recognize this as a very common geek signifier, sported by many women (as well as some men, and many people along a gender spectrum). At a zine-making event at a feminist hackerspace in San Francisco in 2014, attended by around fifteen people, I was certainly in the minority, having uniformly bland hair in my natural color.87 At one of the unconference events, also in San Francisco, people claimed there was strategic value in this aspect of their self-presentation: one woman with short brown hair containing vivid pink and green patches claimed that, “hair color is not a solution, but it’s mitigating. It can draw attention, but in a way that’s respectful.”88

In other words, she felt that a bright shock of hair could provide to interlocutors a relatively neutral aspect of her appearance on which to focus their reflexive comments about her presence or appearance. This was also a strategy for genderqueer people: a tall, striking person whose presentation of self did not conform to an obvious binary gender identification said the choice to wear a waist-length, eye-poppingly purple braid was in order to have “a lightning rod for commenting about my appearance. It makes for [more] non-harass-y comments.”89 Taking the measure of these observations, it is evident that no one expected to not receive attention for their appearance. The high degree of reflection about presentation of self (including gender presentation) within diversity advocacy is therefore unsurprising. This reflection, and even self-consciousness, occurred for women (cis and trans), and for people whose identities spanned less normative spots across a spectrum of gender.

As I have suggested above, there are probably reasons specific to tech that account for the salience of nonbinary and queer identity formations in these sites. People suggested that work setups that permit telecommuting, which can include many programming jobs, can be relatively attractive options for people whose gender identities do not conform to normative ones.90 There is also the prevalence of identity play through computing, as discussed by the makerspace founder, above.91 And geek identity has long been bound up with certain kinds of outsider-ness, as described in chapter 2. In FLOSS and hackerspaces, geekhood carries echoes of countercultural selfhoods as well: hippies, back-to-the-landers, squatters.92 An early account of the Burning Man festival, an annual countercultural desert bacchanal attended by many in the Silicon Valley IT industry, described it thusly:

There are all sorts here, a living, breathing encyclopedia of subcultures: Desert survivalists, urban primitives, artists, rocketeers, hippies, Deadheads, queers, pyromaniacs, cybernauts, musicians, ranters, eco-freaks, acidheads, breeders, punks, gun lovers, dancers, S/M and bondage enthusiasts, nudists, refugees from the men’s movement, anarchists, ravers, transgender types and New Age spiritualists.93

FIGURE 7.3. Handwritten note calling for “Invisible Queers” informal meeting, PyCon, March 2011, Atlanta, GA. Photograph by the author.

For our purposes, it is notable that members of tech subcultures (“cybernauts, rocketeers”), counterculturalists (“eco-freaks, urban primitives, nudists,” etc.), and folks expressing nonnormative gender (“transgender types”) were all rubbing elbows in the desert in 1995. This cultural formation is both a legacy of the Bay Area counterculture and a progenitor of present-day Silicon Valley culture, as described by Fred Turner.94 In a direct parallel, at the 2011 PyCon, people convened a “birds of a feather” session (a spontaneous meeting not on the official conference program) for “invisible queers” (figure 7.3). Queers was used expansively, including not only nonnormative gender expression and sexual orientation (“GLBTQ folk”), but also “wierdos”95 [sic] and “crusty punks.”96 To “fly your freak flag high” is encouraged in communities that draw from a countercultural heritage where self-exploration and self-expression are valued. This also fits with a mythos that surrounds programming cultures, which have a long-standing commitment to the idea that your personal identity is irrelevant if you can make valued contributions to a technical project. (We should not take this mythos at face value, of course, as programming has also been associated with sexism and heteronormativity,97 but it does constitute a resource for justifying nonnormative personal expression in the context of FLOSS.)

Having established the varying ways that diversity advocates understood and grappled with their mission to expand gender diversity—and to promote an expanded notion of gender diversity—in open-technology communities, I now turn to their diversity mandate as it pertains to race and ethnicity.

Positionings: Ethnicity, Race, Nation

As noted throughout this book, gender diversity (often meaning “more women”) was the most consistent formulation of diversity in open technology communities. This does not mean that it was the only aspect of diversity to which advocates attended. In fact, people advocating for attention to racial and ethnic diversity pushed back on the diversity as gender framing. One person who cofounded a “people of color-led” makerspace in Oakland, CA, wrote in 2014 on a social media platform, “Diversity means more than gender. Blacks and latin@s are conspicuously underrepresented in tech, too. That’s why we started [our people of color makerspace].”98 Gender diversity was very important for the founders of this space too; they were, however, making an explicit effort to situate themselves in contrast to dominant hacker or geek identity in which whiteness has historically been hegemonic.

As noted above, whiteness has been a dominant though often unmarked identity category in the cultural milieu of hacking. The celebrated boy-hero with dazzling mastery over technology has been a media trope since the early twentieth century. Radio historian Susan Douglas writes, “[The public] did not know they were surrounded by an invisible and mystical realm to which youthful wizards such as [radio hams] were privately gaining access.”99 As this statement suggests, there is striking continuity in how radio hams and more recent hackers have been represented, primarily as young men with great technical aptitude whose powers awe the public. For both hams and hackers, though, the public’s attitude of dazzlement could shade into ambivalence; at times, they have been subject to suspicion over their motives and their power to not only do public good but public harm with their technical prowess. Hams pushed back on government efforts to curtail their communicative freedom during World War II, citing the importance of the ham communication network to a public safety mission, and presenting ham tinkering and communication as a “resolutely apolitical” activity.100 Modern-day hackers like Julian Assange or Edward Snowden are familiar with public ambivalence toward their activities as well.

The “electrical priesthood” of white men was elevated in relation to and at the expense of women, rural and lower-class people, African Americans, indigenous people, colonial subjects, and immigrants, as documented by cultural historian Carolyn Marvin.101 For white youth, beginning in the early twentieth century, electronics tinkering was understood as a path to gainful employment in white-collar technical occupations. A typical instance of this cultural association can be seen in a 1955 Popular Electronics cover; we see a young white man wearing a literal white collar while operating ham radio apparatus (figure 7.4). He is almost certainly located in a “ham shack,” a basement, attic, or garage where men and boys carved out a masculine space from the feminine domain of the home, as documented by historian of technology Kristen Haring.102 There is notable continuity between this image and the early days of “home-brew computing” as illustrated in this image from the 1970s, in which a young man has built a programmable minicomputer in his garage (figure 7.5).

FIGURE 7.4. Popular Electronics magazine cover, February 1955.

Though these leisure activities were a proving ground for whites’ entry into technical occupations, by contrast historian of technology Rayvon Fouché has documented how the meaning of tinkering and inventing for African Americans was circumscribed by racism. Blacks were largely denied access to both shop culture and school culture,103 two avenues where white Americans honed their technical skills through informal apprenticeship or formal education and found routes into scientific and industrial cultures where credentialed invention occurred.104 Furthermore, to reprise historical background from chapter 2, acts of black invention could be framed in a negative context: a technological innovation that might be celebrated as an act of “ingenuity” in a white inventor might be received by whites as an act of “laziness” or an effort to sustain poor work habits if advanced by a black inventor.105

FIGURE 7.5. Homebrew computing, ca.1975. For more on the Homebrew Computer Club, see Turner 2006: 115–16. Courtesy of Bob Lash, http://

Thus, returning to the topic of ambivalence toward hackers or hams whose activities might at times be met with suspicion, it is apparent that whiteness has been a resource for white technologists, understood as nonthreatening, “good” actors in society, dazzling wizards instead of criminal threats or layabouts. Electronics tinkerers who were white could cast even their mischief (as practiced by not only stereotypical teenage hackers106 but also, for instance, radio hams who “trolled” the US Navy with obscene messages in the 1910s107) as a stepping stone to cultural legitimacy in the form of high-status white collar employment. Probably needless to say, such behavior would likely be met with harsher social or even legal sanctions for members of social groups whose expressions of dominance (technical or otherwise) would not be celebrated by the wider society.108 Black inventors might not strive for subversion as much as for legitimacy; some were motivated by the goal of acquiring proper credentials to assimilate into white society.109 Upwardly mobile middle-class whites, on the other hand, did not need to assimilate, and their acts of pranking can be understood as an expression of not only playful engagement with technology but also social dominance (though neither hams nor hackers as a class would necessarily acknowledge this consciously).

This historical background illustrates why, as Ron Eglash has argued, geek identity limits the capacity of people of color to take up its mantle whole cloth without critiquing it or innovating upon it.110 Because of this legacy, the people-of-color-led makerspace in Oakland self-consciously called itself a makerspace, not a hackerspace. June, a founder who is East Asian-American, said in an interview, “ ‘Makerspace’ is more welcoming than ‘hackerspace.’ We do a variety of activities here, and we want people to be attracted to us, not to put on [events] where we tell them what to do—we want there to be cross-pollination [between what they are already doing and our mission].”111 June’s comments are revealing. She states outright that the “hacker” label and identity would likely not “attract” many people of color. Though she did not go into detail, the above discussion of hackers as people who enjoy technical problem-solving and are often willing to flirt with mechanical and electronic mischief—such as lock-picking or phone phreaking, as well as probing computer networks where one is not authorized to be112—suggests that members of social groups who have historically been assumed to be criminally suspect, and have been surveilled to greater degrees than middle-class whites,113 might be hesitant to embrace the “hacker” identity. Perez, who self-identifies as a “bi-cultural Latina,” said in an interview that she found the stereotypical hacker aesthetic to be off-putting. As someone who spent a lot of her time in the infosec community (digital privacy and security), she said that the “pressure to have to wear all black and be in an intense vampire movie, [have an] emo or goth [aesthetic]” was, to her, “cultural imperialism, too Anglo, too German.… We don’t have to all be hackers in that stereotypical way.”114 Though she presented this topic half-jokingly, she is serious in her critique that the dominant aesthetics reflected cultural positioning that was literally foreign to her, and which she had to learn how to navigate upon entering tech workspaces and hobbyist spaces. (She said that over the years she had modulated both her femininity and her ethnicity in order to be accepted in tech circles; she claimed that she became more “tomboyish” because she didn’t feel she could express the normative femininity of her cultures of origin in open source, echoing some of the above discussions about gender.)

June, the Oakland makerspace founder, also stated, “there is almost no support for blacks and Latinas—being people of color [in tech] is a different challenge.”115 This comment suggests a number of issues surrounding race and ethnicity in open technology cultures. First, consciousness regarding gender diversity does not necessarily translate to matters of race. She alludes to “challenge” as being part of the allure of tech work—coding, solving problems—but she states openly that for people of color, not all of the challenges are necessarily of a positive or motivating sort. She indicates that, as noted above, whiteness is the most prevalent and often unmarked category of racial identity in open technology, which “others” must position themselves in relation to. And within these “other” categories, there are nuances and gradations that make for a multitude of experiences surrounding race, ethnicity, and belonging in open technology communities.

June discussed her own background as an East Asian American. She said, “Being Asian is interesting because you have some degree of privilege, but [in reality] a lot of Asians aren’t privileged.”116 As American studies scholar Lisa Nakamura has explored, Asians are in a special position in terms of assumed techno-proficiency; this assumed special position elevates certain Asians and Asian Americans symbolically while rendering less privileged Asians and Asian Americans invisible.117 She writes, “The ongoing cultural association with Asians and Asian Americans and high technologies is part of a vibrant and long-standing mythology.”118 Multiple American interviewees with South Asian and East Asian ethnic backgrounds described ambivalence about their experiences with race in technical settings including education, hobbyist or volunteer spaces, and workplaces. Anika, an American woman in her thirties whose ethnic background is South Asian, said that she was sure that when she first tried to learn to program in a college course, she was not subject to as much challenge or pushback from peers as she might otherwise have been. She said, “To be frank, some sort of racism helped me—‘Indians are good at coding’ stereotype—people looked at me as Indian, not as a woman.”119 She opined that she did not have negative experiences with peers questioning her competence because of racial stereotyping, even when she was a novice and not particularly good at coding. She said did not enjoy her first foray into learning to code; she had enrolled in the course in part due to family pressure to study science or engineering and said that when she did not like the course or do well in it, she “used that as an excuse” to evade that pressure. Crucially, though, she did not feel out of place in the environment because of gender or race, and she later returned to learning to code, driven by her own curiosity and being a “power user” of FLOSS applications.120 It is perhaps relevant, too, that Anika’s presentation of self was not especially feminine: when I met her over the course of several events, she sported short-cropped hair, no makeup, a t-shirt, and khakis or jeans. I do not know what her appearance was like years earlier when she was initially learning to code, but it is possible that being seen as Indian first and woman second was a reaction she elicited in part due to how she presented herself. As discussed above, many women* in FLOSS do not present as normatively feminine, and they describe receiving different reactions to themselves based on whether they were presenting as “more femme or more butch,” were made up or not, or were wearing a t-shirt and jeans versus something more formal or more feminine.121

Paul, a man in his late twenties who was active for several years in diversity efforts in the Python community, was also of South Asian descent (his family was from India and he had been raised in the UK and US). He helped launch volunteer-run programs to teach “women and their friends” Python in Boston that were replicated in many cities. He reflected on why there were not more South Asians in FLOSS, which he viewed as especially curious given that they were well represented in many technical fields, and that Indians’ English proficiency is high. (Though FLOSS contributors are based all over the world, English is a dominant language in FLOSS.) Paul said that he himself had been introduced to FLOSS in his youth by a “white kid” at summer camp, and then had pursued this burgeoning interest on his own. But he said that “if you’re an immigrant from South Asia like I am, in your conversations with your parents, it’s unlikely that you would be encouraged to [just] fiddle with a computer.”122 In other words, while he (like the other South Asian-American respondent above) was urged to pursue science and engineering by his parents, the “fiddling,” tinkering, or self-guided exploration—about which nascent hackers or FLOSS geeks are enthusiastic (and which becomes second nature for them)—was not something in his repertoire based on his cultural background. While he did eventually cultivate a fusion of joy, curiosity, and agency in his relationships with computers, this attitude was something to which he was first exposed by people whose cultural background was different from his own. The author of a blog post about South Asians in FLOSS (using Debian as his example) writes that, “My mother reports that schools in India focus on memorization instead of creativity. This can leave little room for extracurricular pursuits [or self-guided exploration].”123 Just exploring, and less practical interactions with computers—such as “finding out about features even if I’m not using them”—were experiences Paul and others had to pursue without family encouragement.124

Along similar lines, Helena, a self-identified mixed-race woman in her thirties, offered insights about the cultural assumptions of many people in open technology circles, including some of those fervently advocating for diversity. Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, she had witnessed over the years a number of initiatives to promote diversity, both in industry and outside of it. These included the birth of hackerspaces and makerspaces centered on women* and people of color, and the unconferences for women* in open technology that I discuss in this book. In an interview, Helena said that her own family background had been precarious in multiple ways; her parental support was unstable, and any economic security was hers alone to achieve. This meant that unlike a lot of other professional colleagues in tech, she did not feel like she had a safety net to fall back on if a venture failed, and she had to contribute all of her own savings and retirement earnings without the expectation of inheritance or family support through an employment lull (leading her to prioritize paid work over voluntaristic enterprises, which she felt set her apart from peers). Living in famously expensive San Francisco, she speculated that colleagues and friends who could afford a lot of time for voluntaristic projects were accustomed to more financial security than she was. She also had not had the opportunity in childhood and young adulthood to explore computing as an affective pursuit; by the time she discovered and fell in love with the “analytical mindset” of coding, she was around twenty years old. Interestingly, she did not feel that she was at a disadvantage professionally per se, but did indeed feel that way in FLOSS. In some ways, she echoed the statements of the South Asian and South Asian American people I quote above whose family backgrounds had not encouraged the same pursuit of the affective dimensions of computing that they observed many white youths’ families had.

And these factors seemed to set Helena apart from many of the other people I met in the course of this research. Her attitude toward many of the diversity advocates she encountered was, if not jaundiced, at least guarded. She questioned the sincerity of people advocating for women without doing the also-challenging work of intersectionality.125 She said, “How many [people in] diversity roles are white women? … White women are not incentivized to advocate for others because they feel what they have is precarious [relative to white men].”126 In other words, she wondered if white women, having struggled for standing and visibility in tech projects, were then inclined to consolidate the power they had, as opposed to continuing to advocate for a greater spectrum of diversity that included people unlike themselves, some of whom might challenge them. She felt that her own ability to find common cause with many (though not all) white women had been hindered by dynamics where white women did not really want to advocate for change beyond improvement in their own stations.127 Helena added that she felt that white women were gatekeepers between women of color and projects and groups trying to do diversity better, because white women, as women, could easily stand in for movement toward diversity. She said that her experience had been, “If you raise anything [critical] as a woman of color, you will get backhanded backlash, House of Cards shit [a television program in which characters engage in political scheming and double-crossing], [they will] not invite you to things, or make up or misconstrue things [about your intent]. It’s really hard unless you have a white female ally.”128

Writing on an electronic mailing list, a woman in India made an explicit critique of what she perceived as lack of solidarity from white women, especially those in the Global North. The incident in question is not especially important.129 Of greater significance is how her words invoke race and reflect differences in global positionings among diversity advocates:

While I appreciate the work being done by American feminists, the focus is entirely on the needs of white American women and the needs and experiences of colored women, especially those women from other nations are completely ignored and negated.… When men do it to women, [it’s] called sexism, so what is the term when white American women silence colored women?130