6

The Conscience of a (Feminist) Hacker

POLITICAL STANCES WITHIN DIVERSITY ADVOCACY

During the June 2013 San Francisco unconference for women in open technology, news broke about a massive leak regarding warrantless National Security Agency (NSA) spying. Only a few days earlier, on June 5 and 6, the Guardian published its first articles showing that US telecommunications companies like Verizon had been handing over user data to the US government and that other tech companies like Google and Facebook had given the NSA direct access to their systems. The immediate reaction by the US government was to defend these programs, with President Barack Obama saying they were correctly and legally overseen by the courts and Congress.1 Another article on June 8 called into question the degree to which Congress was actually performing oversight on these programs.

The revelations were incredible for their insight into the misdeeds of the US security agencies. But they had additional significance in hacking circles, where commitments to both free speech and private communication are dearly held. On June 9 (during the unconference), the Guardian revealed the identity of the whistle-blower, Edward Snowden (with his permission). Stating in a video interview, “I have no intention of hiding who I am because I know I have done nothing wrong,” Snowden claimed that the American people had the right to judge the NSA’s programs themselves. On a lunch break that day, I was sitting with a Anika, a New York City–based woman around thirty years old, and, in what began as a casual chat, she told me that the whistle-blower had just “outed himself and is holed up in Hong Kong.”2 I knew what she was talking about enough to follow, but I was not up to date with this latest information, as I hadn’t been checking the news much since the unconference had started, and the identity of the leaker was brand-new information. To my surprise, she then choked up and started to cry. Delicately, as we were barely acquainted, I asked if she was OK. She became more composed in short order and explained her profound connection with this stranger’s actions. For Anika, Snowden’s revelations as an NSA contractor who had blown the whistle on illegal government surveillance were not only of great importance in an ongoing debate about the correct balance between liberty and national security. She reacted in an immediate, visceral way to his personal sacrifice and identified greatly with his decision to leak this information to the press, fearing for his safety as he was now likely to be subjected to extradition and prosecution. Though she had little more information about Snowden than I did, as someone closely identified with hacking, what she perceived as his bravery and vulnerability hit her like a punch to the gut.

Hacking is not a single set of practices or cultural ethos. It is fruitfully understood by taking a genealogical approach, as suggested by sociologist Tim Jordan, which includes taking notice of what is absent in social phenomena as well as what is present.3 This is particularly useful in understanding whether and how hacking has a relationship to politics and activism. Early threads of hacking, according to Jordan, were centered around altering technologies and manipulating information.4 Hacking sensibilities also included the formation of communities, and the identification of coding as both a material practice and discursive resource. Free software played a special role, as programming “bifurcated between free software and the programming proletariat. The activity of coding is the same for both and individuals may, and often do, occupy both positions but there are distinct roles as a coder for community owned and collectively generated program[s].… This is a broad distinction but it develops and begins to underpin many of the political aspects of coding.”5 Coding took on significance as both a material practice and a discursive resource, allowing people engaged in it to recognize themselves as members of a community and elevating both its status as a practice and the social status of its practitioners within that community. Though these developments may seem obvious from our present standpoint, they were contingent. Furthermore, their significance was not necessarily apparent in the moment, though it was at times crystallized through the circulation of texts like John Perry Barlow’s “Declaration of Independence in Cyberspace” and hacker The Mentor’s “The Conscience of a Hacker” (both of which are instantly recognizable as sacred texts that bind community members).6

Among hackers, there is not, in this genealogical telling, a commitment to political intervention, progressive or otherwise. In fact, hacker culture has displayed many politically regressive tendencies. As has been explored extensively, this includes a strong and exclusionary thread of masculinity.7 In addition, some high-profile proponents of open culture such as Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, have been heavily influenced by Ayn Rand and her so-called objectivist philosophy, which privileges individual power and entitlement.8 David Golumbia has argued that cyberlibertarianism is a dominant mode of belief in Silicon Valley and represents a far-right libertarianism.9 Lastly, the ethos of transgression favored by many hackers contains a strong potential for retrograde political effects.10 This background is necessary to underscore that though this book has focused on the mostly progressive intentions of diversity advocates in open-technology cultures, the political waters they swim in have a history of being populated by people and ideas ambivalent or even hostile toward these intentions.

A later development in hacking practice involved hacktivists who were invested in building tools that were meant to secure the free and open (which also meant secure) transfer of information over the internet.11 This animated some strands of FLOSS with a somewhat different political valence. Since the emergence of the global justice movement (also called the anti-corporate-globalization movement) of the late 1990s, many technology-oriented activists have focused their energies on building tools that remake the internet with the goal of supporting activism.12 This includes FLOSS tools to enhance privacy and anonymity in electronic communication, as well as activist-specific tools and software suites to permit activists to run email and other applications on independently built and maintained software (as well as hardware like servers), pushing back on state and corporate surveillance and enclosure.13 Many scholars have noted that hacking can sound notes of revolt against commodification and alienated labor, more and less explicitly.14 Lastly, leaking and whistle-blowing are also political acts that may be tied to a hacker ethos, as in the high-profile cases of Snowden and Julian Assange,15 among others.

Scholarship on present-day hacking and making in the United States has asserted that much of the impulse that drives practitioners is not about politics. Rather, as Sarah Davies shows, much hacking and making is driven by a desire for community and for participation in leisure pursuit that one finds personally meaningful. This is related to claims that hacking can assume significance as unalienated labor, but Davies argues that a wider politics is actually circumscribed for many participants. She writes, “Contrary to expectations of the maker movement as heralding social change, the benefits of hacking were viewed as personal rather than political, economic, or social; similarly, democratization of technology was experienced as rather incidental to most hackers’ and makers’ experiences.”16 Earlier we have seen arguments about hacking versus making, with some practitioners claiming that making is more apolitical and more about lifestyle, while hacking is more politically charged. While this is a valid critique in some settings—hacking is generally more politically valenced in Europe, for example—Davies’s argument reveals a broader truth about the underspecified politics of hacking. This is an important point—for all the ink that has been spilled trying to nail down what the politics of hacking might be, it is definitely important to note that a significant proportion of contemporary hacking is essentially in line with the original iteration of DIY in the US, a project of suburban postwar homeowners’ infusing a bit of “autonomous production” into their consumption practices.17

What can be concluded about hacker politics? In the main, to generalize about hacker politics is fraught. Anthropologist Gabriella Coleman has written of hackers’ “political agnosticism,”18 but over time she has chronicled an evolving politicization emerging as hackers have responded to perceived threats to their liberties and belief systems.19 And yet, while it would be erroneous to conclude that hacker politics are monolithic, good or bad, neither are they neutral (to bastardize historian of technology Melvin Kranzberg’s famous quote). Any formulation of explicit political stances occurs against the backdrop of general cultural assumptions, which have tended to emphasize altering and controlling technology, which has been related to a liberal—some would say libertarian—impulse that elevates the individual’s exercise of freedom. Where this impulse leads is underdetermined, but not clearly in a progressive direction, nor necessarily tied to a notion of collective good. Part of what is so complicated here, according to Golumbia, is the plasticity that accompanies the ideological accretion around computing and digital technologies:

Cyberlibertarianism’s primary social and epistemic function is to yoke what would have previously been seen as at least liberal if not actually leftist political energies into the service of the political far right, with enough rhetorical padding to obscure at least partly, even to adherents, the entailments of their beliefs. In other words, cyberlibertarianism solicits anticapitalist (or at least anti-neoliberal) impulses and recruits them for capitalist purposes, to such a degree that many believers often do not notice and even disclaim these foundations.20

In other words, for Golumbia, even left-leaning political intentions have the potential to be taken up, transformed, or recuperated as part of a right-wing or even libertarian social and technical project, even in spite of people’s intentions to the contrary.21

An updated genealogy of hacking would include feminist hacking. It would also potentially be broadened to include practices and practitioners who have been excluded by hegemonic accounts of hacking, as detailed in the historical introduction of this book. Feminist hacking is not necessarily immune from Golumbia’s critique about the lurking potential for regressive tendencies, in part because feminism itself is contested and subject to corporate co-optation. But more importantly, for feminists and others, technology is a uniquely challenging site for progressive intervention.

The preceding discussion lays out hacking culture as a medium where diversity advocates’ political intentions are being sown. The rest of this chapter follows the lines of diversity advocacy as they intersect with political stances that relate to diversity advocacy. As will be illustrated below, some political intentions expressed by diversity advocates are quite at odds with a right or libertarian political slant, which potentially inhibits their likelihood for growth in hacking culture. That said, their perhaps unlikely growth in this medium reflects both an urgent grasping for alternatives and the need to grapple intensely with the threat of recuperation by political agendas with which one does not intend to align.

A theme of this book is borders of care: reflexive attention to how boundaries are drawn around what counts as an object of care and intervention. How to set limits on what is a core concern (and thus meaningful intervention), versus what lies beyond, is a challenging aspect of diversity advocacy and a challenge to anyone analyzing this advocacy. As this book has argued, following Leo Marx, technology is a hazardous concept, in part because it enfolds many social and political issues; technology is politics by other means, whether or not this is explicitly acknowledged. Diversity advocacy, I have argued, uneasily blurs a line regarding whether it is intervening in technology for technology’s sake, or whether it is addressing other matters. Though it is perhaps counterintuitive given diversity advocates’ active, agitational stances—already chronicled in this book—I argue that their political stances and intentions are not especially self-evident. In many cases, diversity advocacy sits alongside topics with overt political valences, hinting at them, flirting with them, or disavowing them. This chapter scrutinizes the ways in which diversity advocates navigate other political concerns, and then concludes with a meditation on what is gained and what is lost in technologists’ isolation of the topic of diversity in the midst of a wider spectrum of political concerns.

The following three sections sketch some of the explicit political stances that are audible alongside diversity advocacy, including broader radical activism, antimilitarism, and anticolonialism. They are not mutually exclusive categories, of course. Crucially, I do not wish to imply that all advocates for diversity in open technology hold these political positions, merely that a nuanced accounting of the politics of diversity advocates reveals these stances to be salient in diversity conversations.

Radical Politics and Activism

A pastiche of political intentions was on display in the unconferences I observed. As described earlier, the organizing premise of the unconferences was to support women* in open technology, but this was a general principle. In practice, attendees themselves set the agenda; there was no prescribed program and people organized themselves into sessions based on interest. At the 2012 unconference in Washington, DC, someone proposed a session on “Intersectionality: feminism and other social justice work in technology circles” (figure 6.1). The session did not center on Kimberlé Crenshaw’s use of intersectionality—intersecting social identities and their multidimensional, differential experiences of marginality and power—though this framing was in the background.22 Rather, the session attendees discussed whether and how “geek feminism complements and works with other [social] movement stuff, or ways it might butt heads,”23 in the words of one person. A second session on a related topic was “Using open stuff to create social change/feminist change.”24

A common sentiment across these two days of sessions was that, in many attendees’ primary open-technology circles, there was relatively little commitment to political engagement. (Quite obviously, those who had self-selected to propose and attend these sessions were united in being politically engaged.) Many were puzzled at how far the world of open technology seemed from more engaged, activist stances. A woman from New York with a background in human rights advocacy asked the group, “Is it helpful to think of open source as a movement?” Another person replied, “Not necessarily. A lot of people in open source are not motivated by politics or social justice. It’s actually pretty conservative.”25 Others agreed. Sam, a genderqueer developer from the San Francisco Bay Area reflected:

There is a gulf between tech and [my background in] queer activism. “Tech for the common good” [as a framing] is missing an edge. [I think about] bringing a different or more radical kind of activism to open source or to tech. [If my workplace supports a cause like,] Let’s make sure kids are web-literate, [I am thinking,] What about prison? There are people who really don’t have access to communication.26

FIGURE 6.1. Session proposal, “Intersectionality: feminism and other social justice work in technology circles,” Washington, DC, July 2012. Photograph by the author.

This quote is an excellent encapsulation of some of the dilemmas experienced by people who are oriented to social justice in an environment like open technology. In Sam’s telling, a respectable but anodyne workplace campaign to promote web literacy sparked her to consider communication rights in a more expansive manner, and to land on incarcerated people’s communication rights (which are notoriously curtailed, not only through lack of access but through exorbitant rates charged by the telecommunications industry27). But she balked at raising this issue in her workplace, precisely because of its “edge”; incarcerated people’s communication rights are a less well-known and potentially more controversial site for intervention, and might not seem like an appropriately middle-of-the-road, workplace-friendly campaign. In other words, though in her mind incarcerated people’s communication rights and web literacy were related as matters of open technology and social conscience, this connection would not be apparent to everyone, even those invested in promoting open technology. It is of particular interest that she invoked her personal political commitments when thinking about the workplace campaign. As explored in the previous chapter, lines between workplaces and voluntaristic sites of association blur heavily in open technology. Yet there are established reasons for workplaces, even those committed to abstract notions of the common good, to steer clear of more radical political stances. Thus it is not necessarily surprising that an open-technology enthusiast who is also committed to political radicalism would bemoan missed opportunities for political intervention when an employer (for- or nonprofit) moves to support a more mainstream goal or campaign.

Sam also offered some illuminating commentary on the corporate clamor to recognize and support LGBT people in technology fields. (People in the session then kidded about informal community labels like Homozilla in the Mozilla community, Glamazons at Amazon, and Oranges at Apple, signaling a high degree of awareness of such communities in the industry more generally.) She said that on the one hand, she appreciated that large corporate workplaces in tech had acknowledged the presence of LGBT folks. But at the same time, company sponsorship of a happy hour (“if you’re gay, there’s beers here,” in her words) or a Pride parade float stopped well short of her own commitments in struggles for social and political equality. She said, for example, “My history of activism or queer identity isn’t gonna be the same [as a corporation’s]. Gay marriage is not my battle, my politics are nonassimilationist.”28 These statements reflect tensions for queer communities that have been discussed at length in other contexts, and it is not my intention to rehash them here.29 The main point is that many of the attendees of this unconference were not quite sure what open-technology fields and social justice work had to do with one another, even though some of them were fervently committed to both. Sam also remarked, “I have a background in queer activism, for twenty years. Then when I’ve come into the open-source community, it seems like there’s a gulf. [Even the conversations that are happening] are Feminism 101. Is this what our community is about? Is this what are conversations are about?”30 She wondered, “Who’s even meant when we talk about ‘our community’? For example, the Python community: two people who work in Java shops but [program in] Python, is that a community? People of color, queer people, [oppressed people], are who I mean when I say community—not SeaMonkey [an internet suite developed by the Mozilla community, which grew out of Netscape source code] users!”31 Sam is white, but said, “I learned about race even though I’m white, I learned about disability even though I’m able-bodied, because this was the kind of activism I came up in.”32 Overall, her commentary indicates that she seeks to conjoin radical politics to open technology, but views her comrades in open technology as less politicized, or less politically sophisticated.

People repeatedly circled back to the topic of how they felt open technology embodied inchoate politics. One person said, “free software was bearded guys in the 70s that were supposed to be the radicals,”33 but their legacy was less than she might have hoped. Other people speculated that community building and political consciousness building were particularly difficult in online environments. Sam, the queer developer from the Bay Area, said that she “would like to know more tactics for the internet because [it] is such a special, special place … a horrible place.”34 Here she is referring to multiple forms of antisocial online behavior for which online association is notorious, from flame wars to trolling, much of which is racialized, gendered, or otherwise intolerant. A woman from Boston who had extensive experience at the intersection of nonprofits and FLOSS said in response, “The tactic for the internet is to keep having one-on-one conversations over and over,”35 indicating that she thought people were more likely to be more reasonable with each other if they were not on display, and that free speech absolutism could be curbed when its potentially negative effects on others were less abstract; in other words, if someone objected to perceived hostile speech, the community would benefit from one person addressing another privately, sheltered from escalatory dynamics of piling on or shaming. A developer from Seattle agreed and said that in a project community she helped lead, they had “changed [poor dynamics] by making people see each other in person, but it took three years to turn around nasty, trollish dynamics.”36 All agreed that online congregation en masse coupled with the potential for anonymity—or even just the lack of face-to-face accountability—raised the possibility that voluntaristic groups would experience significant challenges having to do with governance and interpersonal or intra-group dynamics. While no one suggested that in-person groups were immune to negative dynamics, they agreed that groups whose main mode of association was online could be especially susceptible to negative dynamics, or even just the outsize impact of one or two “difficult personalities” or people with a high tolerance for adversarial interaction.37 Political activism in open-technology cultures was understood to face unique challenges.

In another session at the unconference, people touched on their hesitancy to strongly politicize diversity advocacy itself. One person opined that she felt that it was unfortunate that she ought not use a “moral framing” because this might make people defensive about having been exclusionary, so she stuck to pragmatic arguments about building more widely used products and saying, “we’re just not doing as well as we could be.”38 Liane, an organizer of the women*-only unconference said in an interview that she had raised money for the unconference by appealing to men in industry and saying, “wouldn’t you like a more level playing field for your daughter?” but without dwelling on some of her own personal beliefs about power in these domains. She said, “[Many] men are playing a zero-sum game: in order to have wealth and power, you have to keep others from attaining it. There is a class-[and race-based] agreement, let’s keep power with the white men.”39 In essence, she knew that expressing these beliefs to people who did not already share them would be perceived as confrontation, which would undercut her ability to fundraise. Along similar lines, Paul, who ran a number of programs to increase women’s participation in Python, said that he often called his efforts outreach because this was unlikely to be controversial, whereas diversity as a label could set back his agenda, leading to wasting time trying to convince people that rates of participation in FLOSS differed according to one’s social group, and that this differential mattered for the wider FLOSS community (what Sam had called “Feminism 101” conversations). And I observed a presentation on FLOSS “for shy people,”40 which was another way to gently initiate a conversation about being more inclusive without touching the third rail and setting off a full-blown debate about autonomy and free speech, which many open-technology communities are poised to have at any moment. “Shyness” may have been a noncontroversial way into the topic of project cultures and interactions, but it tiptoes around the fact that unequal standing and unequal treatment have been experienced by open-technology participants. It deliberately avoids confronting the dynamics patterned on race, class, or gender that many people report as being a barrier to entry to participation in open technology.

Clara astutely drew several of these threads together. She had a capacious understanding of this terrain, having worked on various technical projects in both paid and volunteer capacities for many years, having quit a job as a systems administrator for a nonprofit institution to work as an advocate for open technology at a think tank, and holding personal political leanings that ran toward social and environmental justice and appropriate technology projects in Global South countries, especially in Latin America. She said that she assumed that some activists were deliberately framing their interventions in language that would enhance their chances of receiving funding but tended to obscure the extent of their radicalism: “[Diversity] advocates often have social justice motivations but work in for-profit organizations that aren’t equipped, much less motivated, to do the right thing for its own sake. So the advocates learn the language that will get an initiative funded, or whatever their goal is.”41 In other words, diversity advocacy could give cover for more radical political intentions, but at the same time, these intentions could be diluted when framed as diversity projects instead of, say, incarcerated people’s telecommunications rights, or queer antiassimilationist politics. The above comments reveal that for some people invested in diversity in open technology conversations, there is a self-evident (though sometimes rather nascent) connection between their engagement with technology and their wider political commitments. But as these comments expose, these aspirations sit together somewhat uneasily: technologists who envision deep connections between social justice activism and open technology are a minority in tech communities. “Diversity in tech” as a discourse may in some ways bridge these commitments, but it also bridges to agendas where a robust commitment to social justice is plainly more muted.

Opposing Militarism

At the 2012 Hackers on Planet Earth (HOPE) conference, a panel discussed “DARPA funding for hackers, hackerspaces, and education: A good thing?” in front of an overflowing audience. The panel was moderated by Mitch Altman, who had caused a significant ripple of controversy when he announced his refusal to participate in that year’s Maker Faire, on the grounds that the Maker Faire organization had accepted Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA, an agency of the US Department of Defense, DoD) funding. Featuring fire-breathing robots, product demos, and spaces for children to play with circuit boards, Maker Faire is an exposition space sponsored by O’Reilly media’s Make magazine. It was first convened in 2006 in the San Francisco Bay Area and has since branched out to several more cities in the United States and Europe. It is a significant event and ritual space in the contemporary maker cultural movement.42

Known for inventing a “TV-B-Gone” remote control device that turns off televisions and for cofounding the high-profile San Francisco hackerspace Noisebridge, among other accomplishments, Altman is a widely respected figure in hacker circles and a regular feature at hacker conferences and in hacker media. The panel discussion included Altman; a hacker who had somewhat ambivalently accepted DARPA funding for a program in his hackerspace focused on space exploration and colonization; a hackerspace founder who posited that she had no ethical problem interfacing with the military in order to aid humanitarian intervention and thought hackerspaces were good places to discuss resiliency and “the coming zombie apocalypse;”43 and a librarian involved in bringing hackerspaces and libraries closer together. They held a lively discussion, reaching consensus that this was an important topic for hackers to consider, but no further conclusion. As one panelist said, “One of the things I’m concerned about is, if you grow a piece of celery in red water, it’s going to be red. If you are at Google, and you get 30 percent of your time to work on [your own] project, that’s [still] going to be related to Google[’s priorities], [so] I’m just wondering how this DARPA defense contracts money is going to influence these projects.”44 Another panelist said that a potential negative aspect of accepting this funding is that DARPA ultimately has a “military goal,” which “means that anything you do in relation to them is, in effect, furthering the military prowess of the United States, which means you are in effect a secondary supporter of a machine that [exists] for the functional purpose of military conflict, in short, killing people or defending people.” He drew a direct line between military conflict and DARPA funding, however distant this connection might seem from inside a hackerspace.

The librarian said that he worried that having DoD-funded hackerspaces in high schools would draw closer together STEM education and military recruitment. He said that “while DARPA does not recruit, military recruiters have a presence in high schools and they are extremely interested in STEM education.”45 He cited a recent article on military recruitment that encouraged recruiters to go into STEM classrooms, as well as research that indicated the prevalence of military recruiters targeting students from working-class backgrounds and communities of color. He was therefore concerned that hackerspaces in high schools might be used to facilitate military recruitment, which would be illegal (because under US law it is illegal to recruit children for military service who are under seventeen [and under eighteen under international treaty46]) and, further, unjust (targeting youth from poorer and racially minoritized backgrounds for military service perpetuates these communities shouldering a disproportionate burden).

It is important to note that 2012 was only a few years into the global economic crisis caused by the financial industry’s reckless gambling in the subprime mortgage market in the United States. The moment at which DARPA was offering grants to hackerspaces and to Maker Faire (to put makerspaces in high schools and thus cultivate STEM mentoring and education) was also a moment that saw the slashing of the budgets of public schools and libraries, often quite drastically. The librarian on the panel felt that grant-based (and especially DARPA) funding clashed with the civic mission of libraries and the ethos of most hackerspaces. He said:

There are very few neutral places left in the world. And if you think about the public library, anyone can come to the library and read basically whatever the hell they want, look up whatever you want. We are completely neutral, and we’ll defend your right to read and look at whatever you want until the bitter end. That’s why we’re here. To a large extent, that was my original interest in hackerspaces. The model is very, very [similar.] It’s a neutral space where you can come in, you can destroy whatever the hell you want, set it on fire, we don’t care.47

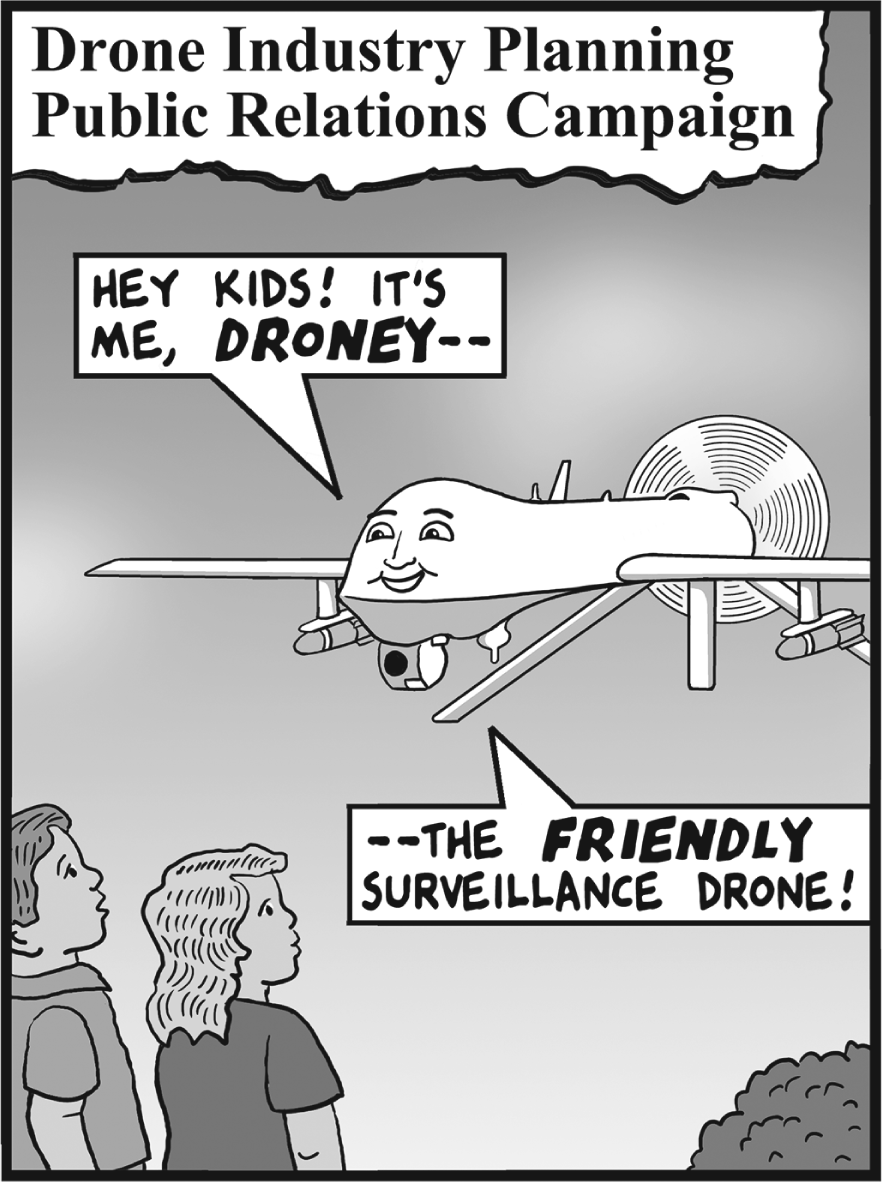

By contrast, he felt that schools and hackerspaces would necessarily be affected by having DoD sponsorship and would no longer support more “neutral” forms of exploration or knowledge creation.48 He also expressed concern that the DARPA grants to fund makerspaces in high schools would be unevenly administered, with wealthy high schools having more ability to control how their makerspaces were run, and other schools having fewer resources and less quality control: “We’re seeing the [funding for public institutions] go like that [hand gesture of decline]. It’s gonna be, like, substitute teachers working for a couple dollars a day, with instructions on a sheet of paper [that say] ‘you just teach what’s on this paper and shut your face,’ and then the military recruiters [step in and] say, ‘Yeah, I can do that for you.’ ”49 In other words, he was concerned that DARPA involvement in education might both reflect and contribute to economic and social stratification; he saw an alarming pattern in civic and public institutions losing funding and militarized institutions stepping into the breach. He also discussed the possibility that students would have less freedom at DARPA-funded spaces, with less making (or destroying) “whatever the hell you want” and more focus on designs for artifacts like—he posited—unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, drones). He cited literature that, he claimed, could be read as a statement that a goal for DARPA in these educational spaces was to “inculcate a military design methodology in high school kids”50 (figure 6.2). Other panelists pushed back on this, saying that DARPA was unlikely to recruit for the armed services directly, or even for DARPA itself, because DARPA usually contracted with industry for engineering work.

FIGURE 6.2. A “friendly surveillance drone” addressing children, satirized by cartoonist Tom Tomorrow, 2012. Copyright Tom Tomorrow, https://

There is merit in the latter claims; in point of fact, DARPA is not directly involved in military recruiting, and supports much military research and development in industry through funding and contracts. Yet in a wider sense, the librarian’s concerns are still pertinent. While it is not necessarily realistic for advances in applied military UAV technology to come out of a public high school, it is certainly the case that the technological designs and applications that are valorized in an educational setting may affect how students view technology and their own relationships with STEM artifacts and careers. And is not a stretch to imagine that such a setting would be a space for ideating an engineering career; indeed, this is a goal shared by educational institutions, Maker Faire, and DARPA alike.51 To have much of the play and education in a makerspace center on, for example, radio-controlled flying objects, and to deny that there is a potential relationship between these objects and militarism, is to be disingenuous at best, considering the history of flight technologies, radio communication, and electronics miniaturization.52 And in subsequent years, ties between makerspaces and military contractors have increased: as of 2017, Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems runs at least five makerspaces.

Moving beyond the more abstract panel discussion, some of these issues can be observed in situ at the Philadelphia hackerspace whose membership had forked in the aftermath of conflict over a sex-toy-hacking workshop (described in chapter 3). Clara, the former board member who had left the hackerspace, later told me she thought militarism was another unstated aspect of the conflict over values in the space. Though no longer active in HackMake, she continued to occasionally read traffic on its email list. She described a posting where one member of the hackerspace had enthused on the space’s electronic mailing list about a design for a one-winged UAV designed for surveillance. Similar to the shape and properties of a maple tree seed spiraling through the air, a prototype had recently been tested and a video released of its flight (figures 6.3 and 6.4).

Hackerspace member Ian posted the video on the mailing list, along with his congratulations to Jim, another member: “Look what Jim’s been doing! Good Job Jim!” Since Clara knew all the players, she explained that Jim had, at work, been involved in the development of the prototype, which Ian, Jim’s friend and cohobbyist, thought was neat and wanted to share with other space members.53 She said, “[Jim] is a very, very sweet and smart member who happens to work for Lockheed, I think. but [military-industrial] complex for sure.”54 In her time with the hackerspace, she claimed that no one had ever explicitly questioned whether their hobby shaded into technology that was being sponsored by the military or developed by military contractors like Lockheed Martin. But she didn’t think this was because no one was thinking about it; rather, she said that “[because] of social ties, there’s a politeness incentive to de-politicize the [conversation] … [But that] larger topic [does come] up a lot at my dinner table b/c we have 3 MIT grads under our roof[.] Where do MIT grads go to work? Sili[con] valley or defense contractors … There’s actually a lot of social incentive to be polite about the politics of this stuff.”55 She noted that on the mailing list, another member, Alan, next proceeded to ask Ian about the technical aspects of the prototype. She astutely pointed out that Alan may have diverted the conversation about the prototype to a discussion of its physical properties as a strategy to avoid what might be an uncomfortable conversation for members about politics, which no one wanted to have. (This email exchange occurred in 2013, after Altman brought the topic to the fore in hacker communities in 2012.)

FIGURE 6.3. UAV prototype modeled on a maple seed, 2011. Courtesy of Lockheed Martin Corporation.

FIGURE 6.4. Maple seeds. Courtesy nlitement/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0.

A few years later, in an interview, another member of the hackerspace, Liam, told me that the space had mostly avoided an overt discussion about militarism, in part by passing up opportunities for grant funding that might bring the issue to a head among members. He said the question was moot because “we’re not cool enough for DARPA funding. We’ve got a member who works for the navy, he does cool top secret shit on his day job, [but] he comes to us [to make an] art car for a sculpture derby.”56 In this statement, he implies that “art car for a sculpture derby” is both too low-tech and too far afield to raise any issues of the presence of militarism in the space. He also suggests, likely accurately, that this member of the space is simply a technology enthusiast who enjoys tinkering and making in his spare time.

Then, somewhat to my surprise, Liam also volunteered that a member who had owned a lot of guns had passed away. He said, “He was the one who would bring guns to the space … He [was] a friend, you’d say ‘I don’t feel comfortable [with that],’ but he doesn’t care … [Also] in the case of the zombie apocalypse, he’s the one I’d go to.” This comment suggests that his own discomfort with the other member bringing guns to the space was mitigated by their friendship and was not great enough for him to draw sustained attention to the matter. Though passed off in a rather tongue-in-cheek, silly comment about the “zombie apocalypse,” his comment and a similar one above by a HOPE panelist does suggest that hackerspace members are not unfamiliar with survivalist tropes. I also observed this in the Oakland makerspace led by people of color. Notably, the Oakland makerspace’s use for weapons needed after the apocalypse included hunting and archery, but not guns explicitly. They were perhaps imagining a gentler and less well-armed future than some other hackers.

In any event, given that Philadelphia has a strong pacifist Quaker tradition, and that hacker culture had begun to debate whether it should accept DARPA funding in 2012, it seems likely that by the time of this 2016 interview HackMake had a culture that tacitly endorsed militarism enough that people who would be especially troubled by weapons in the space or by uncritical celebration of military-contractor-developed technology would probably join other local spaces instead (perhaps the one to which the would-be sex toy hackers decamped). Liam concluded, “We avoid the ethical discussion by not seeking funding, we don’t do grants. We’d have people on both sides of that debate, for sure.”57 It is interesting that he suggested that their membership structure, based on dues and not grants, allowed them to skirt ever making this an open topic for debate or forcing the hackerspace to codify its position. In any event, this also bolsters Clara’s observation that people often avoided bringing up these topics out of a “strong social incentive to be polite.” Given that this was a technical hobbyist space, not a politically oriented one, and that members were known to work for both the military and companies that were recipients of military contracts, it is understandable that to bring up one’s concerns about militarism might seem confrontational. But the level of comfort with weapons and military technology some members exhibited was not something she shared. Indeed, even Liam, who was a close friend of the person who brought guns to the hackerspace did not feel it was especially appropriate, but neither did he make an issue of it.

In spite of HackMake’s tacit acceptance of the presence of militarism in their space, it is clear that some in the hacking milieu were less than acquiescent. Altman, for example, was opposed to the normalization of militarism in hobbyist spaces. Another panelist at the 2012 HOPE conference (on a separate panel) alluded to these issues in his talk when he quipped, “I think it’s great that DARPA is now working with Make magazine because the next inventor of napalm could be a kid.”58 This barbed, sarcastic comment stood in contrast to other stances hackers might adopt about weapons technology; an “apolitical” technophilia might incline some to argue that weapons are “neutral tools” to be figured out and mastered.59 On the panel about hackerspaces and DARPA funding, another panelist argued that, even though she “might wish” the military were not sharing cultural space with hackers, it was naive to not accept that they were here and try to learn what could be learned about technology and/or use their presence to promote technological enthusiasm. Specifically, speaking of drones, she said that a “quadcopter” (UAV design) had “delivered [her] a beer the other day, and that was pretty cool.”60 (This is an instantiation of the “neutral tool” argument, of course.)

It is to be expected that people expressed a multiplicity of ideas and values with regard to militarism in hacking communities. Altman launched the panel discussion by stating that the hacker community was one he valued for its range of opinions, and what he primarily hoped to accomplish was a respectful discussion that would make people think, which he said was what he most embraced in this community. Being thoughtful, and even being wary of weapons technologies, does not necessarily dispose one to opposing militarism. Sometimes people who have extremely strong feelings about weapons technologies, like atomics weapons scientists, hope to engage with these technologies in order to control them (and even prevent their use). Other reasonable people might disagree and choose to engage in activism around disarmament.61 That said, hacking communities demonstrate in some cases a lack of consideration about whether their civilian activities potentially amount to military public relations (or even research and development). For reasons including technophilia, belief that technologies are neutral tools, and not wishing to have uncomfortable political conversations in hobbyist spaces, hackers often appear to sidestep the potential politics of the artifacts with which they are joyfully tinkering. Some diversity advocates are more attuned to these thorny ethical issues. One person in the 2012 unconference for women* in open technology noted in the session on soft circuits (sewing with conductive thread to make electronic circuits, described in chapter 4) that these creations could have military applications, even though they seemed like domestic crafts projects. And as Clara put it, “These folks [mainstream hackers] are generally not disciplined appropriate technologists, so they’re not aware of, much less [trying to build] around, the issues of communities who are victims of all the militarized stuff to begin with.”62 For Clara, there was a difference between being a techno-enthusiast and someone who had thought deeply about power relations and ethics in relation to technology—in other words, a “disciplined” technologist.

Some of these issues gained wider traction in 2017 and 2018, the first years of the Trump administration in the United States, when organized coalitions of tech workers challenged their firms on major government contracts. Two prominent examples were workers advocating that Microsoft not build a database that could assist Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE),63 and that Google cancel its involvement in Project Maven, a proposed deployment of algorithmic machine learning in war zones.64 Obviously, there is a long history of interdependence and collaboration among industry and the military and academia,65 so it remains to be seen to what extent these challenges may be effective in articulating less militarized visions of tech work.

Global Positioning Systems: “Decolonizing Technology”

Clara’s comment about “communities who are victimized by militarized stuff” raises the topic under consideration in this final section of this chapter.66 In interviews, field sites, and online, some advocates for diversity in open technology pondered not only identity categories (further explored in chapter 7) but also reflected on how difference is generated through spatial, economic, and political relations. Such advocates expressed concern that the technologies they on the one hand embraced so fervently were on the other hand implicated in colonialist or neocolonialist relationships, which undercut their liberatory potential.67 Diversity advocates sought to name and explicate these relationships as an antecedent to recuperation of technology.68 Self-identifying as a “white-passing Latinx” person who had lived in and worked on projects in the US, Europe, and Latin America, Clara herself had a highly reflexive awareness of relational differences in power and position.69

For example, in their call for participation in the 2016 feminist hacking convergence, organizers wrote,

We take as a starting point the assumption that colonialism has invaded and embedded the digital realm and our technologies in general.…

How then can we imagine the decolonization of technologies and of cyberspace? What would such processes, epistemologies, and practices entail? How can feminist anti-colonial, post-colonial, and/or indigenous frameworks shape and strengthen our analysis in our collective reflection on such questions? … We will explore the intricacies of colonial technologies while at the same time trying to conceive what decolonial technologies mean.70

Here the organizers invoke feminism, indigenous,71 and postcolonial or anticolonial frameworks and suggest they be brought to bear on technologies and cyberspace, suggesting that the best possible basis for praxis requires analysis and reflection on these issues. In practice, this orientation was rather vague. As postcolonial theorist Edward Said writes,

“The colonized” was not a historical group that had won national sovereignty and therefore disbanded.… The experience of being colonized therefore signified a great deal to regions and peoples of the world whose experience as dependents, subalterns, and subjects of the West did not end—to paraphrase from Fanon—when the last white policemen left and the last European flag came down. To have been colonized was a fate with lasting, indeed grotesquely unfair effects.…

“The colonized” has since expanded considerably to include women, subjugated and oppressed classes, national minorities.… The status of colonized people has been fixed in zones of dependency and peripherality, stigmatized in the designation of underdeveloped, less-developed, developing states.… To be one of the colonized is to potentially be one of a great many different, but inferior things, in many different places, at many different times.72

In spite of rigorous empirical and theoretical attention to these issues in certain academic subfields, as Said’s quote illustrates, there is a reason for the looseness surrounding discussions that invoked colonialism (or decolonization) in open-technology circles. Even as a nonspecific concept, it satisfied advocates’ desire to attend to geopolitical, spatial, and economic inequities deriving from the hegemonic positions of certain nations or peoples relative to others. In terms of advocates’ use of these concepts, we might take Said’s description of “the colonized” as “dependents, subalterns, and subjects of the West” as both literal description and figurative approximation (and indeed Said goes on to describe how this concept has been malleable enough to include various “subjugated and oppressed classes” such as women, national minorities, and others73). In a variety of forums, Global North technologists reflected on the interplay between their encounters with technologies (especially their commitment to hacking, and their association of technology with agency) and the troubling and polluting origins of those technologies, as well as technology’s ongoing implication in Western economic and political dominance, including settler colonialism.74

A variety of empirical examples peek through field sites. Soliciting participation in the feminist hacking convergence, organizers recognized that their event would be convened on colonized land. In their words, “We acknowledge that we are proposing the [event] to take place on the traditional territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka. The Kanien’kehá:ka are the keepers of the Eastern Door of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. The island of ‘Montréal’ is known as Tio’tia:ke in the language of the Kanien’kehá:ka. Historically, this location was a meeting place for other Indigenous nations, including the Algonquin peoples.”75

During the event, participants acknowledged that their acts of cultural and material production were situated within the Global North and dependent on materials and labor extracted from the Global South.76 As described in chapter 4, a burgeoning Montréal activist hardware group hoped to assert autonomy from labor, extraction, and postuse processes they perceived as exploitive by repairing discarded computers. They sought to shorten and localize the chain of production and consumption, recirculating repaired machines running free software within their local community. There is reason to believe that this would be an extremely difficult process to enact on a large scale; computer hardware is, quite simply, not designed for long life or simple repair. It is, conversely, designed for obsolescence: “a high rate of machine turnover marks a condition of tremendous profitability for the computer hardware and software industry[ies],” in the words of Jonathan Sterne.77 Nonetheless, a member of this aspiring group listed as their goal, “Recycling with partners that don’t ship to dumps overseas, getting to zero waste, or as close as possible.”78 (North American electronics recycled by well-meaning consumers and institutions often wind up in unregulated sites in the Global South such as Agbogbloshie, outside of Accra, Ghana, where precious metals are reclaimed under conditions that are extremely hazardous to workers’ health.) Fervent about hacking, the aspiring Montréal collective sought to reposition it as a social and material practice. Aware of the dirty and exploitive conditions of electronics’ production and postuse, they hoped to divorce hacking from the exploitation of people in the Global South and the environmental degradation upon which it currently rests.

A promotional poster for a feminist hacking event convened at an anarchist autonomous collective in Catalonia by some of the same people a couple of years earlier suggests similar critical awareness of Global South–Global North relations. Here, feminist hackers have appropriated an image (Uterine Catarrh) by Wangechi Mutu, a Kenyan artist working in the United States, and imposed on it text advertising their event, a “trans futuristic cyborg cabaret,” including the words “gender hacking, anti capitalism, libre [free] culture, anti-racist, anti-sexist” (figure 6.5).

Mutu’s piece depicts a gynecological exam (replete with scientific instrument—the speculum—and flowing white vaginal mucus, “catarrh”) set between the eyes on a white skin mask partially covering the face of an African woman depicted in a hyperprimitivist fashion. There is a vivid grotesquerie to this visage, which absorbs a colonial and scientific gaze, and maybe gazes back. It is impossible not to wonder if there is a deliberate association with Frantz Fanon’s famous book exploring colonial domination, Black Skin, White Masks. Thus, a politics of liberation including anti-racism, gender hacking (echoing cyberfeminism), and free culture are all linked for the feminist hackers.

FIGURE 6.5. Feminist hacking event poster, 2014. DIWO, or doing it with others, is a less heroically self-reliant DIY.

Other actors talked about these dynamics in less abstract terms. Perez, a US-based activist who identifies as a “bi-cultural Latina” said in an interview, “Some of my closest friends are developers from Cuba, they didn’t learn how to really code [code extremely well] until they moved to Spain [where computing resources were not scarce]. [In Cuba,] the Cubans had to build their own computers, find parts, construct their own computer. University gave you some hours on the internet, but speed is really slow. It’s a testament to how smart they are to figure stuff out in these environments.”79 She described the Cubans initially learning programming by writing out code longhand with pencils at home, and then running it on university machines later, with much lag time in between. She compared this with her own experience learning different programming languages, where, she said, if she encountered a problem her existing knowledge base didn’t prepare her for, she could just “go in and Google it.… If I didn’t have the internet, I wouldn’t have been able to do that.” Perez observed that while her Cuban friends might feel their coding skills were inferior when they encountered people from the United States or Spain, she saw this in opposite terms: they had learned so much with scant resources, which demonstrated grit and ingenuity beyond that of many programmers who had learned their skills in the Global North.

Relatedly, STS scholar Anita Chan found that FLOSS activists in Peru were enthralled by the possibilities they imagined for upending historical dependencies experienced by their nation and region of the globe. However, they encountered a disconnect between their own interests in programming and their university computer science classes. She quotes an activist recalling a dean who had said he “should not dream of working with Bill Gates in Redmond,” and was discouraged in his university study from learning more advanced programming associated with operating systems, as this was “not for us [Peruvian] students.”80 According to him, the university administrator reinforced a notion that innovation in computing was not to originate in Latin America; these countries were destined to be dependent on technology that would be created elsewhere. The activist perceived great limitations in the university-sanctioned vision of computing education, which urged him to orient to the needs of established local businesses.81 By contrast, when the activist came to FLOSS, he ascribed to it meaning as a tool for agentic personal growth in the vein of hacking, and as one with national significance, offering “new potentials for developing other pathways towards [Peruvian] technological, political, and economic independence,” in Chan’s words.82 Of course, using closed proprietary software such as Microsoft cost Latin American governments and institutions a great deal in licensing fees, which FLOSS by definition did not. Technological and political sovereignty are bound up together in numerous ways.83

This being said, FLOSS still struggles in many ways with the hegemonic presence of Global North culture. In his ethnography of FLOSS in Brazil, Yuri Takhteyev describes how Brazilian FLOSS programmers predominantly code in English because it keeps their code consistent with global, professional coding practices—even though it is an option to use Portuguese for some aspects of their code—and because English is already encoded into the grammars of the programming languages themselves.84 Others echoed the notion that FLOSS cultures themselves needed examination. On an email list discussing an upcoming unconference (that was never convened), one person said that she would be interested in talking about “free culture/open source from a decolonial/critical perspective that challenges the rather imperial ethos embodied by organizations [like] the Electronic Frontier Foundation (basically trying to approach the ‘free’ movement from an anti-oppressive place rather than the anarcho-libertarian ethics of most of the orgs run by white men).”85 In other words, she claimed that mainstream or Western FLOSS culture had not examined how it potentially reproduced imperial power vis-à-vis groups trying to enact “open culture” in other places, with different emphases and values. Another woman, based in both the United States and Latin America, elaborated in a list discussion about white or Global North feminism, “[A]s someone that lives between US and latinoamerica I can totally see the two different FLOSS worlds.… The different organizers need to really understand … the importance of hav[ing] a diverse tech community (that also [extends beyond] gender diversity).”86

The Montréal convergence’s intentions to explicitly attend to the topic of decolonizing technology were in practice undercut by the fact that many of the people they had hoped would attend the event to lead workshops on these issues failed to show. Some of us met to discuss the topic anyway. One of the convergence organizers explained that the subject had originated at an event on Afrofuturism, where a panelist had raised the issue of cultural diversity in hackerspaces, not only gender diversity. She also said that she had reached out to people at eco-camps, antiracist, and indigenous-led groups she knew. It is impossible to know why the people she had solicited did not attend, and it is certainly true that this event—which took place on the heels of the World Social Forum (WSF) in Montréal—was competing with other meetings and events, and was weakened also by significant levels of activist fatigue after the WSF. Nonetheless it is notable that this event was a very genderqueer but mostly white radical feminist hacking meeting. The absent activists perhaps approached the intersection of technology and liberatory politics differently, possibly with critical ambivalence,87 or they may have equivocated about attending a mostly white event.

Though many of the above examples are relatively utopian and even abstract, they suggest that some Global North activists who had been thinking of diversity in more identity-based terms were starting to think about geopolitical power relationships and how this affected the terms of their activism. Advocates were, of course, invested in a high-tech, digital future; they were, after all, brought together by a shared interest in FLOSS computing and hacking more generally. At the same time, they were committed to locating the artifacts and practices of open-technology production within culture, space, and history.

By contrast, some actions by industry players underscore the obduracy of relations critiqued by the above advocates. In 2015, Mark Zuckerberg pushed to introduce a service called Free Basics in India, which would have given people complimentary limited internet access, with Facebook at its center. In 2016, the Indian government banned Facebook’s service, citing net neutrality.88 Critics such as American technologist Anil Dash chided Zuckerberg, advising him to “reckon with the history of western corporate powers enforcing their desires on a broad swath of the Indian population, especially India’s poorest … a colonialist ‘trust us, it’s for your own benefit’ pitch is a hard sell.”89 Indeed, technologists are often implicated in impulses to solve perceived problems in the Global South with Global North tech fixes. At a Google-hosted reception for the 2013 women in open technology unconference in San Francisco, attendees were ushered into a hall where a video played, featuring women entrepreneurs in a hardly elaborated African country who produced handmade bracelets, underscoring Google’s commitment to fostering women’s value and ingenuity;90 the video also celebrated practices of financialization through microlending.91 Audience members were then encouraged to look under our chairs for gift bags, Oprah-style, which contained Google swag such as branded water bottles, lip balms, and the bangles featured in the video, which revealed themselves to be iterations of Google’s logo (four thread-covered hoops in Google’s colors; I wound up taking mine home but always felt I had no use for them and eventually donated them to an internal recycling area of my apartment building when I moved, a few years later).

This feature of the Google reception (like much of the rest of it) was met with dismay by the unconference attendees, many of whom were not convinced that this pablum-laced presentation had much to do with the gender-in-tech issues they perceived as important. The video imputed to its audience a feminine reform mentality and belief in commodified (branded) empowerment. While many in the room were women who cared about Africa in a broad sense, there was palpable discomfort about being drawn into these issues on the terms laid out by Google, which contained an undercurrent of “saving the Other.” I inferred that many were also at a loss about what to do with feminine jewelry, even more than I was. With this audience, which was largely ambivalent about traditional femininity, and suspicious of white savior narratives, Google’s bangles were an awkward misfire.92

Conclusions

As noted in the introduction of this chapter, it is difficult to generalize about hacker politics, but we have seen moves in explicitly political directions with the rise of hactivism, and hackers sounding notes of resistance to commodification and alienated labor. (This is not to say that “apolitical” strands of hacking ever actually lacked politics, of course.) What the above discussion demonstrates is that feminist hacking should be included in an updated genealogy of hacking.93 Of course, feminist hacking, like feminism itself, is not monolithic, though it may be safely be generalized as fusing hacking with values of care. The chapter’s opening vignette, wherein the unconference attendee was moved to tears by the actions of Edward Snowden, illustrates care: Anika burst into tears because of the intensity of her affective care for Snowden’s well-being, and for the political ramifications of his whistleblowing. Far from pwning or dominance, hacking here was closer to platonic love, as elaborated by bell hooks: it included care, trust, honesty, and commitment (to community and to principle).94 A couple of years later, I interviewed Anika more formally in New York, and she spoke of herself valuing what she called “the numinous.”95 She explained that one of her parents had training as a priest and she understood both coding and teaching as having almost spiritual dimensions; the joy and the intensity of them were in their best moments shot through with something almost divine.

This chapter has broken out a few strands within feminist hacking—radical politics in general, antimilitarism, and anticolonialism—from the concerns of diversity advocates. In describing these topics, I in no way wish to imply that advocates have necessarily accomplished their intentions; I outline them in order to demonstrate that these topics have attracted attention and given rise to articulations. These topics are important because they shed light on what is at stake for the people using hacking to critique both hegemonic hacking culture and aspects of the world at large. Diversity is but one of many political goals these hackers of community are seeking to effect in open-technology cultures.

Advocacy for diversity in tech may seem like a potent issue of justice. This is especially true in our current moment, in which men’s rights activists challenge women’s presence in the electronic public sphere,96 when neo-Nazis coordinate online to march emboldened in the streets, and when even Google firing engineer James Damore over workplace expression of his views on gender essentialism is a flash point. But it is important to remember, as Golumbia cautions, that some left or liberal impulses in tech have the potential to be recuperated for purposes that do not necessarily align with their proponents’ intentions. Diversity, though a wedge issue in a culture war, is in fact having a long moment where it is becoming part and parcel of corporate and neoliberal mandates. It has been cleaved from necessarily having anything to do with justice, as Sara Ahmed has so thoughtfully explicated. The political interventions discussed above, falling under loose headings of left or radical politics for their own sake, antimilitarism, and anticolonialism, have arguably less potential to be recuperated in this way. This makes them very important as critique, as imaginings of a fuller-throated invocation of justice in the context of technological development and practice. But at the same time, for that very reason they may be less likely to flourish in tech culture outside of these iterations, which are (and can likely only be) at the margins, not the mainstream, of tech culture.

One reason for this is that voluntaristic tech communities are still tethered to workplaces in significant ways. In the words of Johan Söderberg, “A programmer might freelance for a multinational company three days a week, spend two days as an entrepreneur of a FLOSS start-up venture, and in the meantime he [sic] will be a user of software applications, all of which are activities that feed into the capitalist production apparatus.”97 In other words, even off-the-clock use of software or innovation on one’s own time are never very far from aligning with capitalist relations; at the same time, one is socialized to view one’s own creative labors as authentically recuperable from instrumental workplace relations.98 This constant blurring accounts for both San Francisco programmer Sam’s impulse to bring up her own radical politics in a work campaign around web literacy as well as her immediate realization that a campaign at a corporate workplace was not an appropriate place to critique the prison-industrial complex in the United States. Contemporary creative economies are suffused with an “upbeat business-minded euphoria,”99 which makes them resistant to the exercise of certain forms of critical agency. Many kinds of political language may be seen as alienating to colleagues, and to customers. Instead, Sam brought this up in a more hospitable setting, the unconference, but as a lament and a ritualistic proclamation of her politics.

It is worth revisiting Clara’s statement, in which she observed a balancing act for people with left politics. As outlined above, she thought that in workplace settings, people with more radical left politics might latch onto diversity advocacy because the latter played well in corporate settings, musing that, “In my experience, one reason they sit together well is because the advocates often have social justice motivations but work in profit-driven organizations that aren’t equipped, much less motivated, to do the right thing for its own sake. So advocates of course learn the language that will get an initiative funded, or whatever their goal is.”100 In other words, she felt that diversity advocacy in organizations might be a useful Trojan horse, allowing money or organizational time to be put toward political agendas that were harder to name outright in these contexts. On the other hand, as she readily admitted, these terms certainly circumscribed the scope of intervention. She humorously continued, “Ugh, I better quit [reflecting] before I start flipping tables!!”

Just as one is never outside of capitalist relations, “there is no vantage outside the actuality of the relationships between cultures, between unequal imperial and nonimperial powers,” as Said writes.101 In an interview, Christen, a German biotechnologist and activist for internet freedoms and women in STEM, pithily remarked, “I am just waiting for some hackathon organized by white people to make ‘an app for Africa’ or something.”102 Here she objects to hacker solutionism (and, slyly, to discourse that lumps African nations and peoples together as a monolith103). But she also points to one difficulty for hackers against colonialism: they are always already implicated in relationships of dominance and dependence. This is true for any person on earth, but it is uniquely true for technologists, who are so often called upon to execute political mandates under the guise of neutral technocratic intervention. It is difficult to ascertain exactly why no indigenous activists and few people of color showed up to the 2016 feminist hacking convergence in Montréal, for example, but the absence of these constituencies does underscore the potential difficulties of starting an anticolonial project centering on technology and specifically hacking.

Lastly, the Philadelphia hackerspace’s polite tiptoeing around militarism illustrates the accretion of values and interests around electronics and computing that render them friendly to casual association with war, whether or not this is consciously articulated. Historian Paul Edwards has argued that the Cold War did not represent a new technological dawn but a continuation of World War II and the transference of a mythic, apocalyptic struggle onto a new enemy, placing computing at the center of this conflict.104 Though this history is undoubtedly far from the minds of most hackerspace members celebrating a new drone design, the association has a sedimented history behind it that cannot be dislodged casually. This is why the DARPA debate at the HOPE Conference is so important. (Of course, there is nothing inherently liberating or peaceful about FLOSS: it does not matter if the drone that bombs your village was programmed using FLOSS.105) In his study of nuclear weapons scientists in North America, anthropologist Hugh Gusterson notes that there is a long-standing cultural commitment to working out issues of discomfort with militarism privately and alone, which he calls a process of “socialized individualism and collective privatization.”106 In other words, partly out of professional politeness, the ethics of weapons work are confronted alone, not in the professional realm. Again, the contiguity between norms of the workplace and of voluntaristic spaces has real consequences for what is politically articulable.

This is not to denigrate these ideations as goals for technologists—or for the society at large. Rather, the act of planting them here, in this medium, begs a question of whether they should be aimed at tech cultures or self-consciously cultivated in a wider milieu. The question of scale once again appears as a crucial issue; while it is a wholly understandable impulse to direct critique at one’s immediate environment (especially an environment where one perceives acute problems), voluntaristic, local interventions may experience difficulty upending the edifices upon which technical cultures have been built. Inequality in tech cultures is an outgrowth of the fact that technology as a domain is vested with many social and political agendas that are not progressive, including technocratic, corporate, and capitalistic values that progressive diversity advocates directly contest. Technology cultures may—and do—breed resistant strains, but they may also prove to be especially hostile terrain for antiracist, anticolonialist, antimilitaristic, and just thought and practice to root and grow (as illustrated by the person who said she felt she was prevented from using a “moral framing” for her concerns). Technology is a uniquely challenging medium in which to plant and grow resistant politics. Yet there is also opportunity here: naming antimilitarism, anticolonialism, and antiracism as in bounds for care in technical communities—as feminist hackers have begun to do—can create a compelling starting point by shifting the terms by which tech culture is analyzed.

1. Mirren Gidda, Guardian, “Edward Snowden and the NSA Files Timeline,” August 21, 2013, https://

2. Fieldnotes, June 9, 2013, San Francisco, CA.

3. Jordan 2016.

4. Jordan 2016: 5.

5. Jordan 2016: 6.

6. Jordan 2016: 7. Though Jordan does not spell this out, these future-facing titles also reach back toward Enlightenment tropes and values.

7. Jordan 2016; Jordan and Taylor 1998; Nafus 2012; Reagle 2013.

8. Rosenzweig 2006: 119. According to David Golumbia, “[Wales] is not merely an avowed libertarian but a follower of Ayn Rand so devout that he named his daughter after a character in Rand’s novel Anthem” (2013b). Thanks to Nathan Ensmenger and Matt Wisnioski for help tracking down some of these traces.

9. Golumbia 2013a, 2013b; see also Borsook 2000; Kelty 2014; Turner 2006.

10. See Chen 2014; Coleman 2012b, 2015; Phillips 2015.

11. Jordan 2016: 10. Less important for the present discussion, hacktivists also launched electronic mass actions like civil disobedience and demonstration tactics in online settings (Jordan 2016: 10). Antecedents here include radical techies of the 1990s (Milan 2013).

12. Juris 2008; Milberry 2014. See Wolfson 2012 for a critique of this.

13. Milberry 2014.

14. Milberry 2014; Söderberg 2008. Though see Golumbia 2013a, 2013b for discussion of how some of these politics are potentially less progressive than proponents may intend.

15. Coleman 2017. Writing in the New Yorker, Raffi Khatchadourian stated that, “For Assange, there is no real difference between a hack and a leak; in both instances, individuals are taking risks to expose the secrets of institutions” (2017).

16. Davies 2017a: 1.

17. Gelber 1997. Gelber rightly points out how DIY was a practice of masculine identity construction, important when suburban homeowners might have had white-collar jobs removed from a hands-on, brawny masculinity (see Douglas 1987). While contemporary hacking expands DIY to include feminine craft/DIY practices, its practices are still largely (neo)traditionally gendered.

18. Coleman 2012a, conclusion.

19. Coleman 2017.

20. Golumbia 2013a: 3–4.

21. It is not coincidental that many believers do not necessarily notice or engage the contradictions. Rather, “negative liberty” is conceptually intertwined with “positive liberty,” and a notion of collective freedom must include an account of individual freedom; they cannot be understood in isolation from one another, so potential for slippage in political valence is great (Berlin 1958 as discussed in Kelty 2014).

22. See also the 1977 Combahee River Collective Statement.

23. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

24. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

25. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

26. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

27. Kukorowski 2012.

28. Fieldnotes, July 11, 2012, Washington, DC.

29. For example, Warner 1999.

30. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

31. Fieldnotes, July 11, 2012, Washington, DC.

32. Fieldnotes, July 11, 2012, Washington, DC.

33. Fieldnotes, July 11, 2012, Washington, DC. See Ensmenger 2015.

34. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

35. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC. She also said that she believed that nonprofits were positioned well to understand and utilize the “freedom and empowerment” aspects of nonproprietary software, but that “then you [FLOSS] called us [nonprofits] stupid [for not adopting FLOSS],” which set back relations. See McInerney 2009 for more on the nonprofit sector and use of FLOSS.

36. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

37. Reagle 2013; Reagle 2017.

38. Fieldnotes, July 10, 2012, Washington, DC.

39. Interview, July 24, 2014, San Francisco, CA.

40. Fieldnotes, June 2011, New York, NY.

41. Personal correspondence,—to author, December 28, 2016.

42. See Sivek 2011.

43. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

44. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

45. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

46. Child Soldiers International n.d.

47. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

48. Of course, knowledge is never neutral. Yet his point about the sudden loss of municipal funding for civic, public institutions stands; see Klein 2007.

49. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

50. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

51. See O’Leary 2012. Drones in particular have been taken up with remarkable fervor by the DIY/Wired magazine set. In 2009, Wired magazine editor Chris Anderson launched a new venture, a website entitled “DIY Drones,” which by 2012 boasted over 30,000 registered users. He described the mission of DIY Drones as “open sourcing the military industrial complex.… In two years, we have begun disrupting a multimillion-dollar industry with the open-source model.… We can deliver 90 percent of the performance of military drones at 1 percent of the price” (Takahashi 2012).

52. Thanks to Peter Asaro, Chris Csíkszentmihályi, Seda Gürses, Wazhmah Osman, and Madiha Tahir for conversations about these topics; and see Asaro 2012; Osman 2017; Parks 2016.

53. The prototype received celebratory treatment in tech press, such as a 2011 article on Geek.com entitled “Lockheed Martin wants a fingertip-sized UAV in every soldier’s backpack” (Humphries 2011).

54. Shared in personal electronic chat with author, April 11, 2013. Names are pseudonyms.

55. Personal electronic chat with author, April 11, 2013.

56. Interview, July 29, 2016.

57. Interview, July 29, 2016.

58. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

59. Winner 1988.

60. Fieldnotes, July 15, 2012, New York, NY.

61. Gusterson 1996.

62. Personal electronic chat with author, April 11, 2013. See Pursell 1993 on appropriate technology.

63. Upadhya and Tech Workers Coalition 2018.

64. Tarnoff 2018.