11

MAKE THE IDEA BIGGER, NOT THE LOGO: OR, WHY BRANDED CONTENT IS MORE INTERESTING THAN ADVERTISING.

IN MY OFFICE AT FALLON, THE FUTURE of all advertising was changed with one brilliant idea. No wait, not my office, it happened in the office just down the hall from mine, actually. That's where the creative team working on BMW entirely changed the course of advertising history. (Honest mistake. They were just two doors down from my office.) In that office, the BMW team came up with an idea that disrupted everything everybody knew about advertising.

Before that time, the accepted wisdom was this: if a brand's annual media spend for advertising was x, then its agency could spend no more than 20 percent of x to produce all the advertising—every single ad, billboard, commercial, photo shoot, all of it had to be covered in that 20 percent.

But Fallon's pitch was the opposite.

“Okay, you know all those TV commercials we usually make? And all the print ads we publish? And all those media schedules we normally spend months planning? Yeeeeaah, we're gonna go ahead and throw all that out and take the year's entire budget and give it to some Hollywood peeps. To make eight movies. C'mon! Whaddaya say?”

The concept was called The Hire, a series of short movies starring Clive Owen as a driver-for-hire, all directed by A-list Hollywood directors (listed in Figure 11.1) and all available for free on the web. The first one to air, Ambush, was directed by John Frankenheimer and it was so not a commercial. There was no voice-over prattling on about the engine's horsepower. It was just Clive Owen, driving a BMW 740i like a bad-ass all over some city as he tried to save an old man in the back seat from a van full of bad guys.

In The Art of Branded Content, Marcelo Pascoa described it this way:

What [they] bravely proposed was nothing short of a complete inversion of this so-called principle [of limiting production budgets to 20 percent of the media spend]. Its approach was to invest most of its marketing budget into production, believing that the quality of the content would lead consumers to the campaign without the usual massive media effort to reach them. The brand put its money where its mouth was and changed the relationship between entertainment and advertising forever.1

For the first time, an advertising campaign wasn't being proposed as an interruption but as a destination—bmwfilms.com. So many people went to this destination the server crashed more than once. Today, The Hire is rightfully crowned as the first massive success in what we now call branded content.

Another early example of branded content, one which people paid to see, was The Lego Movie. I thought it was a funny movie while The Guardian's film critic had a more guarded response: “It wasn't a great film, but it's a brilliant commercial.” Andrew Essex in The End of Advertising, put it nicely:

For advertising to survive it must add value to people's lives. Advertising will have no choice but to compete as primary content, not secondary intrusion. It will become the thing, not the thing that sells the thing… . [And about The Lego Movie, he added] For the first time in a long time, the thing that normally sold the thing had become the thing itself. Just a good movie, about a brand, brought to you by that brand. It was primary, not secondary.2

Branded content can be a feature film, but it can also be a free movie online, a concert, a Q&A chat room, a blog, an app, a downloadable video game, or just a stupid free ringtone. It can be almost anything if it has entertainment value or is something a customer might find useful.

Today all brands, big and small, have to be in the content business. Many brands and agencies have added content studios to their capabilities and this has created new opportunities for copywriters and art directors to be content creators. Best of all, it frees visual storytelling from the restraints of the 10-, 15-, and 30-second blocks of time broadcast networks sell. Long-form content opens up vast opportunities.

So where do we start? As always, with the customer.

Know your customers and what matters to them.

You've probably seen this diagram before (Figure 11.2). If you haven't, it's called a “purchase funnel.” (Creepy name, I know.) For years it's been the go-to visualization for how people moved from no brand awareness to consideration and finally to purchase. But not anymore.

Advertising used to work primarily from the top of the funnel generating awareness until a brand had a happy customer, even a brand ambassador. Along the way, in-store salespeople, point-of-purchase, and, of course, recommendations from friends would also inform customers (during CONSIDERATION) and help close the deal. If everything aligned just right, reinforcing both emotional and rational purchase criteria, someone might ultimately buy your car or widget or whatever you were selling.

The problem with the purchase funnel today is the average buying process is no longer this linear. Paid advertising isn't necessarily the first thing a customer sees anymore. The side view of the funnel leads you to assume it's a smooth slide down from top to bottom.

But if we could somehow look over the top of the funnel and see all the forces in play, we might see something more like an M. C. Escher labyrinth. Up is down, down is up, and there are entries and exits all over the place. Today, customers can find their way right into the middle of the funnel's purchase process via search, a blog article, a link on Twitter, or a pin on Pinterest. There are many pathways for customers to bump into a brand.

Figure 11.2 The old version of the purchase funnel. Today, the path from awareness to purchase is neither smooth nor linear.

Online spending has gone nuclear because every brand, even the big ones, can afford only so much for paid media. But in the ether of digital, the only real costs are production budgets, and so a brand really can be online everywhere their customers are.

This requires agencies to engineer a brand's presence across the entire web. Engineering this presence, as digital expert Andy Blood says in the next chapter, means building a “content ecosystem.” It's his way of describing a campaign's architecture online. To build such an ecosystem, we create different content for each medium with an understanding of what a brand's customers are doing there.

So, we study the people in those communities. What are they doing, what are they interested in, and how can our brand improve their lives? In some ways, this isn't much different from what we do with paid advertising. We need a clear sense of the people we're trying to have a conversation with.

In a previous edition, author Edward Boches offered a smart checklist to help frame your thinking as you approach creating branded content.

- BRAND/PRODUCT: What is it, what does it do?

- ITS TRUTH: What is the single truest thing you can say about your product or brand? Be completely and totally honest.

- FEATURES: What distinguishes it, defines it, makes it special?

- BENEFITS: What are the benefits of those features?

- ONE WORD: If you had to convey your brand in a single word, what would it be?

- BELIEFS: Does this brand have a bigger purpose or reason for being? How does it share beliefs or values with its communities?

- COMMUNITY/USERS: Is there an existing community that's a source of content and creative ideas?

- USER INTERESTS: What is happening right now—in the news, in entertainment, on the internet, in real life—that the brand's community is paying attention to or cares about? How can it be leveraged?

- STORIES: What are the brand's stories—real or created for inspiration—that can be told? Consider the brand's history and what customers have said about it.

- MEDIA: Where do your target customers spend their time? What particular platforms? How will the platforms' technologies affect what you create?

- INFLUENCERS: Who are the influencers? Can you collaborate with them? Use them as media channels?

- UTILITY: What could you make or do for those communities?

As you can see, Boches's list starts off sounding like a creative brief for advertising in traditional media. But with the addition of digital, it's as if we've moved from playing regular chess to a 3D version of the game. We still must tell our brand's story, but the dynamics of how we do it here are targeted more tightly to specific audiences and are more fluid and connected.

“In other centuries, human beings wanted to be saved, or improved, or freed, or educated. In our century, they want to be entertained.”

—Novelist Michael Crichton

THE HARD PART: COME UP WITH SOMETHING THAT WORKS FROM BOTH AN ENTERTAINMENT AND A MARKETING PERSPECTIVE.

In The Art of Branded Content, Pelle Sjoenelle wrote, “Finding the intersection between your story and your brand is the ultimate goal of branded entertainment.”3

It's like we're back to our Venn diagram and we have to hit a different sweet spot. This is tougher than it sounds because it's hard enough coming up with an interesting story, but now your story must align with a brand's mission. This is a delicate balance because if you focus too much on the narrative, viewers may dig your idea, but not get any brand messaging.

Sjoenelle agrees we must focus first on creating great entertainment, but we also have to make sure “the entertained audience does not leave without somehow knowing the brand was involved in the joy.”4

I have a more prosaic way of describing this. Consider the problem of giving a dog a pill. Dogs hate pills, right? What most of us do is wrap the pill in some bit of meat or perhaps a doggie treat. Well, it's kinda the same thing with brand messages, because people hate brand messages. So, we have to wrap the brand right in the middle of something yummy. The two have to be one.*

Your cool idea cannot just be a “brought to you by the makers of” thing. It has to come from, be inspired by, and carry the brand DNA itself. It must also be relevant to the target audience. PJ Pereira says, “If you make it impossible to talk about the idea without the brand, yet make it interesting enough to generate some buzz, you have something special on your hands.”5 His observation almost perfectly describes an extraordinary branded-content campaign from CHE Proximity for Virgin Australia Airlines.

In a spoof that felt like a series of episodes from “The Office,” the campaign pretended an intern working in the airline's frequent-flyer-rewards division, Velocity, had made a mistake announcing the big new “Million Point Giveaway.” In an email sent to half of Australia, it was mistakenly called the “Billion Point Giveaway.” (You know, just a small typo, really.)

Hours later, the airline sent another email (Figure 11.3, left) headlined, “1 Billion Points, what were we thinking?” But the copy below it promised, “After speaking with our lawyers, we've decided to honor the mistake and commit to giving away all of the 1 billion points.” Then the real campaign began.

The agency created 40 different videos documenting the trauma happening inside a TV version of the airline's rewards department (Figure 11.3, right). Said creative director, Ant White, “Our biggest creative opportunity these days is to find ideas that allow us to create content to stay watchable for [a] long period… . We wanted to make this work feel like we were covering a ‘live event,' rather than creating a couple of films that lose relevance over time.”6

Over the month the campaign ran, the name of the giveaway changed from “The Billion Point (That Was Supposed to be the Million Point) Giveaway” to “The Billion Point (Deny It Happened. What Billion Points?) Giveaway” and even “The Billion Point (Now Hiring New Interns) Giveaway.” People shared the videos online and ultimately it was the most successful rewards campaign in the airline's history, returning $6 for every $1 the brand invested in it. What makes it even more brilliant was the strategic issue that led to the whole idea: research had shown not enough Australians trusted Virgin's rewards program.

Figure 11.3 The agency decided not do an “advertising idea” for Virgin's frequent flyer program. Instead, they came up with “an idea worth advertising.” A brilliant mockumentary about an intern's mistake.

Figure 11.3 The agency decided not do an “advertising idea” for Virgin's frequent flyer program. Instead, they came up with “an idea worth advertising.” A brilliant mockumentary about an intern's mistake.

After this, they did.

Think like a publisher.

The explosion of digital channels has created so many places to post content, our challenge becomes how do we regularly crank out things that entertain, help, or amaze people?

Part of the answer is having a plan. Most agencies or brands map out their editorial calendars, so they know what they'll be doing every quarter, month, or week.

If it's a big brand, it's likely they'll be publishing two kinds of content: one kind's called stock, the other flow.* Stock content is bigger and lasts longer. One good example is the “Billion Point Giveaway” mentioned previously. Stock content is worth investing in and taking the time to make great because it can last for months, if not years, on a client's website or YouTube channel. Unlike campaigns in paid media, which air for a time and disappear, a branded content campaign can be “always on.”

Stock is a brand's assets and flow is more like income. Stock is always there but flow: it comes and goes. The value of flow is how it's renewable, flexible, and responsive. Flow content appears daily in the feeds of a brand's social channels and maintains their presence with customers in between periods of paid advertising. For example, the “Chicken Pot Pie–Based Meditation System” campaign KFC ran on Instagram was stock content (Figure 11.4, left). As an example of flow, they had a short partnership with crochet artist and put up some goofy KFC things you could crochet, and the patterns were included (Figure 11.4, right).

One way agencies create flow is factoring it into the editorial calendar and making it as needed. Another is to take cues from conversations currently going on in the social sphere and then weigh in with content. A third way is to curate and share useful information and links—to make the brand a resource to customers. That means learning to consume content as well as produce it.

Figure 11.4 KFC stock content: “The Pot Pie–Based Meditation System” campaign, left. KFC flow content: KFC crocheting posts, right.

“To create content in real time you have to consume content in real time,” argues Noah Brier, cofounder of Percolate. “Brands don't do that naturally, so they need to learn how.” Brier believes the better a brand becomes at consuming content, the sooner it can align with its customers' interests and find ways to stay culturally relevant with its own content. Some brands produce a lot of content, and to keep up creatives must get used to coming up with and executing ideas quickly.

As with any commercial creativity, there's a discipline here, and as you sit down to create branded content, you must have an objective. Why are you making it? For whom? Consider, too, what purpose it will serve. Can you come up with something that's part of a larger, more important conversation? Can its purpose be to help make the world better, have an opinion, or support a cause?

Brands should, in fact, have opinions, and many do, but most clients avoid this because they think taking a side on anything might lose a customer. (Remind you of politicians?) Fortunately, 70 percent of Millennials and iGen say they lean toward brands that support causes,7 and according to Sprout Social, people are overwhelmingly open to brands participating in social and political conversations. “Not only do they want to hear from brands, they expect brands to converse in intelligent and impactful ways.”8 (We'll revisit corporate responsibility and connected capitalism in Chapter 17.)

“Think like a marketer, behave like an entertainer and move like a tech start-up.”

—PJ Pereira, Creative Chair, Pereira & O'Dell9

Done beats perfection. Lean toward action.

“Moving like a tech start-up” is a key part of Pereira's maxim, because everything's constantly changing. Things catch fire quickly—news, themes, memes—they're seen everywhere and then poof, they disappear with equal speed.

So, it's smart to lean toward action and embrace a real-time approach to content generation. Learn to target keywords and trends in your social monitoring and in the news. Develop the ability to respond fast to market changes by speeding up the approval process, both internally and with clients. Measure engagement and effectiveness, reframe any failures as learning experiences, and then move on.

Digital expert Tim Cawley says creatives in his company don't put all their bets on one idea and hope they're right. “I say in meetings all the time, ‘I want to give you more chances to be right. Let's make 10 things, and if one message works best, [that's what we go with].”

TELL STORIES WITH DATA.

Every brand you work on will have tons of data and often buried within are cool stories worth telling. Data, even when presented as a static infographic, can be interesting. Many firms specialize in data mining to discover interesting patterns inside large sets of data—whether it's likes on Facebook or purchase behavior on a brand's site.

If you're fortunate enough to work on a brand that's inherently data-driven—Spotify, The Weather Channel, Airbnb—you'll have lots of material to work with: data about what's most popular, what's most frequent, what's trending. But you can also access deep stores of publicly available data all over the web. There's census data, real estate data, flight info, average salaries, even divorce rates. I read somewhere the state of the US economy could feasibly be monitored with satellite images showing how many cars there are in Walmart parking lots on a given day.

As a very small example of leveraging data, I remember doing an online promotion for a cruise line (back when the web was still steam-powered). Most cruises sail from Florida, but many passengers fly in from cities such as Chicago, which in winter, obviously, can get very cold. Using streaming data from the Weather Channel's current Chicago temperature, the discount on our little digital post went up for every degree Chicago went below freezing.

To launch the Puppo brand of dog food in New York City, BBDO Auckland used the city's dog licensing database to generate 100,729 unique ads, every one of which included the dog's name and breed. (The campaign name? “Every Dog Has Its Ad.”)*

Spotify's in-house creative team used data to tell some interesting human stories for its end-of-year outdoor campaigns. They were even able to localize the messages, generating data from a specific city to mention the strange listening behavior of (anonymous) local residents (Figure 11.5).

The best place to find case studies of the creative use of data is online at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. The festival has added Creative Data as a category, inviting entries that display “innovative uses of data that allow brands to tell better stories and drive more meaningful engagement.”

Figure 11.5 Spotify used listener data for urban billboards.

Use “do-invite-capture-share” to get customers to create branded content for you.

Edward Boches came up one of the smartest methods out there for getting people to talk about a brand. He calls it Do > Invite > Capture > Share. Here's his formula, and it's one I've seen work effectively over and over again:

- Do something really interesting, something that communicates the value of your brand.

- Conceive the idea to allow people to participate in it, and find a way to invite them to join in.

- Capture all this created content, or document the event, so it can live beyond the event online.

- Make it shareable across every relevant channel.

Coming up with the Do is the hardest part. It's hard because you can't just come up with an ad or a commercial. For one of these bad boys, you really gotta come up with something that's radioactively creative. Here's how:

Shift your thinking from coming up with an advertising idea to coming up with an idea worth advertising.*

When you adopt this mindset, you'll find you can come up with things more exciting, fun, and (dare I say) easier to advertise than just some product. You'll see why when we get into some actual examples.

Another way to get a big kick-off idea for a Do-Invite-Capture-Share is to apply Alex Bugusky's cool process—you remember: Idea-as-Press-Release from Chapter 9. For that first step, instead of thinking of an ad, come up with an idea—a thing, a product, an event—something so interesting it could be written as a press release as news worth covering.

When you have an idea so cool it warrants news coverage, we might say it also qualifies as being what's called brand activation. Think of a brand activation as a highly creative, highly public jolt to a brand's visibility. It can be used to introduce new products but works equally well in energizing brands to keep them visible and relevant. It's not something a brand says but something it does.

What differentiates an activation from plain old marketing is it usually includes some form of audience participation. Which brings us to step 2, where we INVITE customers to participate. Depending on what our activating DO is, this participation can take many forms. Online, maybe we're asking customers to tweet us new flavors for our brand of chips. Or to post their own shirt designs to our fashion brand's Instagram. We give customers a blank canvas to paint, a podium to rant from, or a game to play—anything that lets people imprint themselves into the clay of the brand in ways that are so beautiful or interesting that when they're done, they want to show it off to friends. What they share is called user-generated content.

The last two steps are mostly process focused. In step 3, you CAPTURE whatever this cool content is, and in step 4, the brand SHARES it. And, more important, fans share it.

When you have big ideas where customers can create their own shareable content, it's something close to a self-funded marketing campaign with an all-volunteer creative department. Because when you capture all that content, it can go on to become a draw in and of itself, beyond your original kick-off idea, and if the online buzz and conversation amplify it, your idea can reach millions of people within a few weeks—all at a minimal cost.

Here's a recent example of this process from ReThink in Canada for their client, Heinz ketchup.

Figure 11.6 Customer-generated content was the centerpiece of this Heinz campaign, used in both outdoor and in a limited-edition packaging run. It's a textbook example of Boches's smart Do-Invite-Capture-Share process.

Figure 11.6 Customer-generated content was the centerpiece of this Heinz campaign, used in both outdoor and in a limited-edition packaging run. It's a textbook example of Boches's smart Do-Invite-Capture-Share process.

The kick-off happened behind the scenes with an experiment. They anonymously asked a large number of people, in five different continents, to “draw ketchup.” They didn't say they were representing Heinz or any other brand. But because Heinz is so popular, they knew what would happen. Most people naturally drew bright red bottles labeled Heinz and many of them even nailed the brand's unique label.

On the left in Figure 11.6, you can see how they used the content in out-of-home. And because they'd filmed the experiment on camera, ReThink released a fun video on YouTube and used several cutdowns of the video for commercials on paid TV.

To add to the talk value, Heinz took their favorite fan drawings and used them on a limited release run of their packaging (Figure 11.6, right). Then they kept the buzz going by inviting the public to submit drawings for a chance to win a new custom bottle featuring their labels.*

ReThink was having a winning year at Cannes when I interviewed their chief creative officer, Aaron Starkman, about Heinz. We then turned to a project they'd just completed for Scott's Turf Builder.

To demonstrate how well their product worked, Scott's applied Turf Builder to a lawn in a public park. After the turf had time to get healthy and green, they set up an installation called the “Scott's Grass Green Screen.” As you can see in Figure 11.7, park visitors were happy to lie on the grass and have their picture taken, after which they could choose from a variety of different backgrounds. During the week the campaign ran, sales went up 42 percent.

It's important to note whenever we invite customers to devote any amount of time or effort, we must come through with some type of payoff. For Scott's, customers received a fun picture to post on their social feeds. Whatever we offer, it should be commensurate with what we've asked of customers, and it can be anything from product samples to digital coupons. Sometimes the payoff can be a memorable WTF experience, as the next example will show.

“Content is eating the world. Content marketing is the only marketing left.”

—Seth Godin

CREATE BRAND EXPERIENCES.

When we create intriguing advertising and tell interesting stories, we invite people to lean in. But with experiential marketing, we can help them fall in.

Figure 11.7 The “Scott's Grass Green Screen” demonstrated their product while giving customers something fun to post.

With experiential marketing we create one-on-one interactions between brands and customers, giving people something to encounter or interact with. Cool experiential ideas can connect brands to people in unexpected and memorable ways. Louis Falco of Cadillac says, “In experiential, we talk about surprise and delight.”10

Experiential falls into two general categories: experiences staged out in the real world (the street, a concert, a mall) or as something to take place online.

FCB&FiRe created a great example of online “surprise and delight” for the launch of PlayStation 5. What started off as an unboxing video on a Twitch streamer's channel quickly turned into a horror movie. As popular streamer Ibai Llanos opened the new PS5, his apartment appeared to be attacked first by unseen demons and then by a maniac with a flame-thrower. It all happened while streaming live in front of 200,000 gamers (Figure 11.8). Directed by Spanish film director Jaume Balagueró, the video accumulated more than 3.3 million views within the first 24 hours.

Physical brand experiences in the real world (or, more colorfully, “in meat space”) can be equally involving and memorable. They can take the form of an installation, a pop-up store, or just an app.

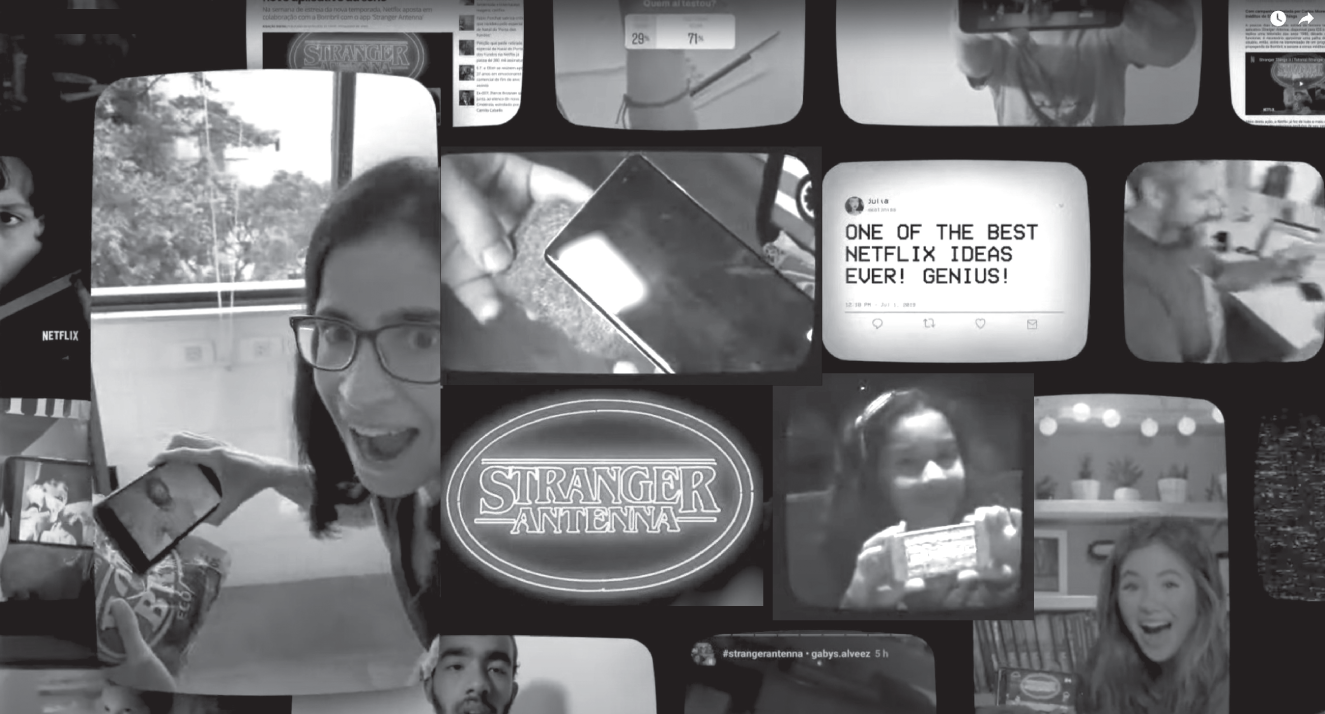

To build anticipation for the third season of Stranger Things, AKQA in Sao Paulo created an app that allowed fans to get sneak previews. But they could see them only by using an old television-reception trick Brazilians remember from the ’80s—putting steel wool on those old rabbit-ear antennae.

Figure 11.8 Online branded content: What started as just a plain old unboxing video of a new game turned into a live horror movie and a WTF experience for 200,000 gamers.

Figure 11.8 Online branded content: What started as just a plain old unboxing video of a new game turned into a live horror movie and a WTF experience for 200,000 gamers.

When fans first opened the app, their screens showed only static noise, like vintage television. But when they put steel wool (or any metallic object) close to the phone, crystal-clear video of advance clips began to play. (The magnetometer inside the phone, reading the wool's magnetic field, is what did the trick.)

People filmed their experiences of goin' all OMG with the app and, by sharing their reactions online, turned it back into content (Figure 11.9). As with many experiential events, if the experience is interesting enough, once captured it can live again online or be turned into commercials for use on TV.

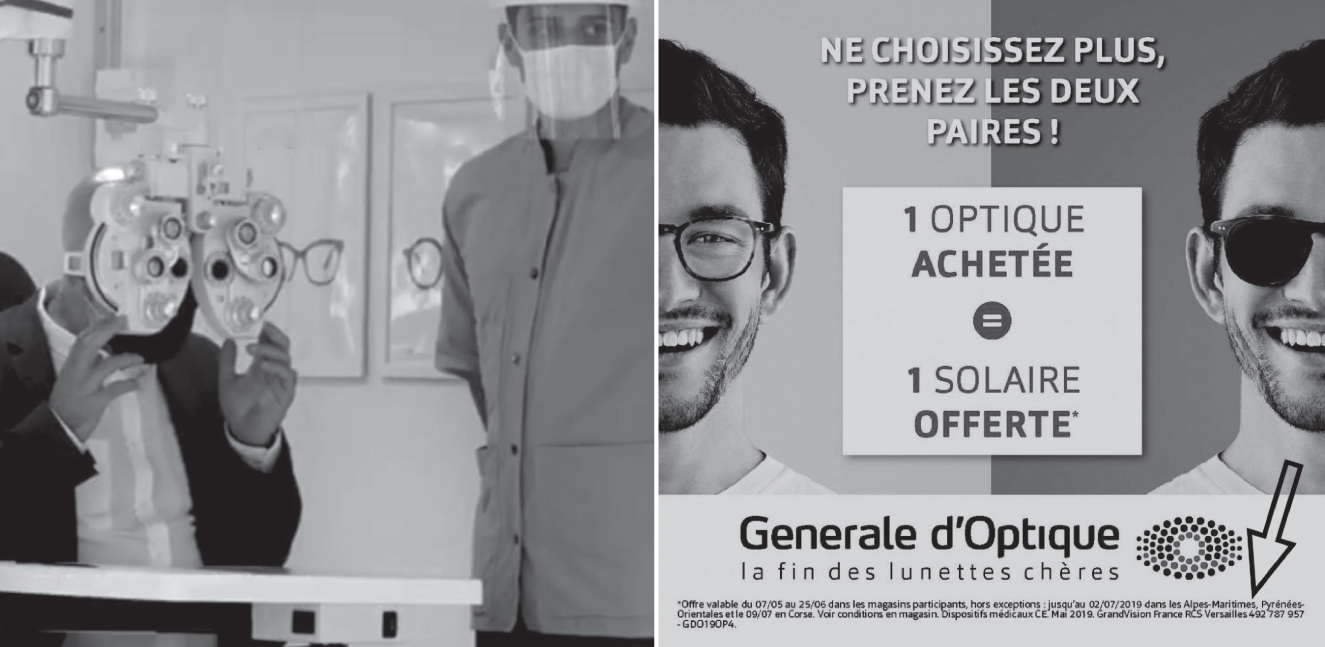

Okay, one last example of experiential marketing. A French chain of optical stores, Droit de Regard, and their agency BETC made fun of the shady advertising practices of competitors with an on-the-street eye test. No eye charts were needed, only the fine print at the bottom of their competitors' ads (Figure 11.10). Volunteers could easily read the ad's big “Buy a pair get a pair FREE” headline. But even with the help of the optician's testing equipment, nobody could read the conditions buried in the fine print. The takeaway? Droit de Regard's up-front pricing is clear, simple, and trustworthy.

Figure 11.9 Experiential marketing stunts can often be converted into branded content.

Figure 11.10 To show its competitive pricing, French optician Droit de Regard asked passersby to look at a competitor's outdoor ad and try to read the fine print. (Note arrow.)

As you continue to study other innovative digital and branded content ideas, it should become clear our creative toolbox is no longer limited to words and pictures. We may still make ads, but we're no longer “ad writers.” As Teressa Iezzi wrote in her book by the same title, we're idea writers now. We're not in the business of just making ads. We place brands into culture.

NOTES

- 1. PJ Pereira, ed., The Art of Branded Entertainment (London: Peter Owen, 2018), 49.

- 2. Andrew Essex, The End of Advertising (New York: Random House, 2017).

- 3. PJ Pereira, The Art of Branded Entertainment, 88.

- 4. PJ Pereira, The Art of Branded Entertainment, 125.

- 5. PJ Pereira, The Art of Branded Entertainment, 276.

- 6. “Velocity & Che Proximity Create Expo to Convince Aussies That Holidays Are Better Than Toasters.” B&T Magazine, October 30, 2017, https://www.bandt.com.au/velocity-che-proximity-create-expo-convince-aussies-holidays-better-toasters/.

- 7. David Baldwin, The Belief Economy (Austin: Lioncrest Publishing, 2017), 70.

- 8. “Brands Get Real: Championing Change in the Age of Social Media,” SproutSocial.com, July 18, 2021, https://sproutsocial.com/insights/data/championing-change-in-the-age-of-social-media/.

- 9. PJ Pereira, The Art of Branded Entertainment, 263.

- 10. Limelight webinar on YouTube, “The Future of XM and Events,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OgSIRB998u0.

- * No, I don't equate customers with dogs. Dogs are better. Please register your complaints at biteme.com.

- * The terms stock and flow date from about 2011 and are no longer in wide use in discussions about online content. But they're still a useful way to think about content scheduling.

- * The issue of personalization and privacy is beyond the scope of this book. I just work here.

- * This famous observation is credited to the brilliant strategist Gareth Kay.

- * Great work requires great clients, and clearly Heinz is one of them. In fact, their client, Nina Patel, head of brand build and innovation at Kraft Heinz, talks like an agency creative director. In an interview, she said her team “evaluates ideas bearing five things in mind: is it authentic and ownable to the brand? Will the press write about it? Does it have inherent tension and a point of view on the world? Does it offer something consumers can authentically engage in?” (Strategy, Spring 2021 issue).