3

Types of Business Writing

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Set up a business letter in the correct format.

• Name the main parts of a memorandum.

• Describe what the minutes of a meeting are used for.

• Cite the main purpose of written proposals and reports.

• State eight things to be explained in the body of a proposal.

As we’ve said, a main purpose of business writing is to communicate ideas so that some action will occur. There are other ways to do this, of course, and you may not always select writing as the best form of communication for your purposes. Writing leaves a record, even when it is sent from computer to computer. Written communication is generally more formal than conversation and less personal than a phone call, and it doesn’t allow for the back-and-forth exchange that is particularly useful when you’re batting an idea around or considering a strategy. E-mail is a kind of in-between communication: less formal than something on paper, but no less faceless and, at times, more anonymous. It allows for a quick and simple exchange, though, which may be exactly what you need in some circumstances.

Many situations require written communication, however. It may be important to create a lasting record, or the complexity of your message may make it more efficient to put it on paper, where it can be reread and reconsidered at the reader’s pace. Other times, courtesy, custom, or the delicacy of a situation demand that you take the time to compose your thoughts carefully and observe the etiquette of the culture in which you work. All of these factors go into deciding what form of communication is best suited to your message.

Most of the formal business writing you do will fall into four main categories: letters, memos, proposals, and reports. In each case, what we’ve said in previous chapters applies: Before you start writing, you need to know your audience, adapt your writing to their needs, and organize your ideas and information. Then you’re ready to write.

Word processing programs generally offer predesigned formats for letters, memos, reports, and a host of other documents. This is useful knowledge to have in your head as well as your machine, however, so we will review the formats here.

THE BUSINESS LETTER

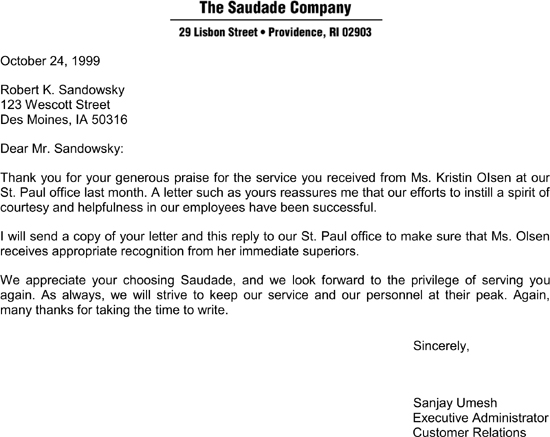

Perhaps no form of writing requires that you identify your audience more than a letter. The reason is simple: You address a letter to a specific person or group. In many ways, this makes letter writing the easiest kind of writing to do. Because you have a clear idea who will be reading your message, you can keep that person in mind as you write. Letters have the added advantage of following a standard format. You’ll find an example of the correct format for U.S. business letters in Exhibit 3–1.

Format

Letters are single-spaced in block format. That means that you don’t indent the first line of a new paragraph, but do leave two lines between paragraphs. Business letters are usually written on letterhead, which has a business address printed somewhere on the page. If you don’t use letterhead, you need to type an address to which your reader should reply at the top of the page, either on the right- or left-hand side. (You may want to design and store your own letterhead on your computer to use for your own letters.) If you are writing to a different country, be sure to include USA after the zip code. Then, on the line directly below your address, type the date.

Two lines down at the left-hand margin comes the internal address. This is the name, title, and address of the person to whom you’re writing. Make sure that you spell names correctly, use the correct form of address, and get titles right. This is one of the most basic rules of etiquette (and common sense), yet it often goes unheeded.

Next, two lines below the internal address, comes the salutation or greeting, which is followed by a colon. It is always best to use the recipient’s name, if you know it. Unless you are on a first-name basis with your reader, use his or her last name and an honorific: typically, Mr., Ms., Mrs., or Dr. is generally reserved for physicians, so unless a person with a Ph.D. has signed a letter to you as Dr. So-and-So, you will be on firm ground using Professor or one of the general forms of address.

In most places, Ms. has become an all-purpose form of address for women, regardless of their marital status, and equivalent to Mr., which is used for all men. However, some married women prefer Mrs., so follow the lead of the person to whom you’re writing; if she has identified herself that way, you should too.

If you don’t know the name of the person you’re writing to, or if you’re writing to a group of people, try to find a brief, inclusive, nonsexist title or description, such as Dear Director of Research, or Dear Design Staff. If that isn’t possible, use Dear Sir or Madam. Avoid false familiarity (Dear Friends, to people who aren’t your friends) or cuteness (Hiya, Fellow Toilers in the Field). Humor can be a great social lubricant, but only in appropriate circumstances.

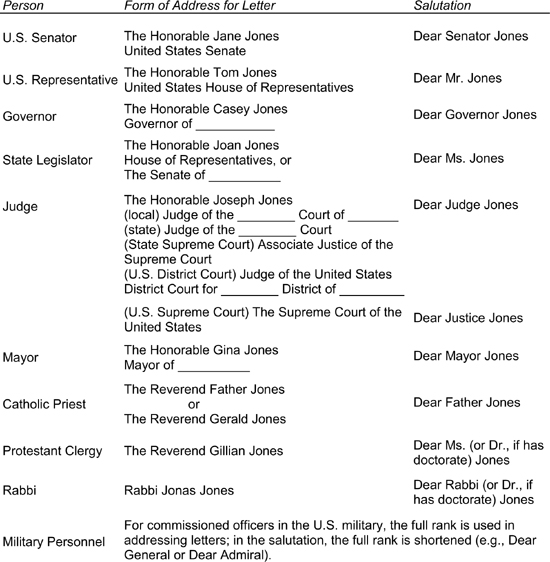

Occasionally, you may need to write to a politician, judge, or person in the military or a religious order. Exhibit 3–2 lists the proper forms of address for these individuals.

In a letter, the greeting is followed by the body, or message. The letter then finishes with the closing. As with the greeting, fight the urge to be breezy, clever, or glib, and stick to the standard closings, Sincerely, or Yours truly. Drop down four spaces and type your full name and title. In the space between the closing and your typed name, sign your name by hand. Use only your first name if you are well-enough acquainted with the letter’s recipient, if that person has signed a letter to you with only a first name, or if the situation seems to call for informality. Otherwise, sign your fall name.

Body of the Letter

Business letters should be concise and to the point. They are generally one or two pages long, though length is determined by what you need to say. In the first paragraph, explain clearly and directly why you are writing. If you’re writing at someone’s suggestion, mention that person early in the letter; a familiar name often moves a letter to the top of the pile. If you’re making a request, make it tactfully, but don’t bury it under qualifiers or apologies so that it is unclear what you want.

Let’s look at an example. Suppose a colleague tells you that her old boss at another company will soon be hiring a Director of Information Services, for a new office, and he has asked her to keep her eyes open for good candidates. The position hasn’t been advertised, but your co-worker encourages you to express your interest, which you do by sending your resume and a cover letter. Your letter might begin in this way:

Melissa Rosen, with whom I work at Sky’s the Limit, told me that you plan to hire a Director of Information Services at your new office in Santa Cruz. She suggested that I send my resume for your consideration.

The second paragraph of your letter might highlight or elaborate on one or two significant points in your resume, and a third paragraph might state specifically what you think you would bring to the job. For example:

As my resume shows, my training and work experience have focused on information technology. I minored in computer science as an undergraduate and have kept current with developments in the field in postgraduate courses. Here at Sky, I have been named to the Innovators Honor Role two years in a row and received several letters of commendation for the technology training programs I developed in my position as Assistant Manager of Technology Services.

I believe I would be able to bring to your company a combination of experience and openness to new ideas. Having recently completed a six-week course in electronic marketing, I would like the opportunity to work with a sales department to implement the techniques I learned there. I understand that you are interested in exploring the potential of this exciting new resource too, which makes the position particularly appealing to me.

In general, middle paragraphs give information or suggest a course of action. As in all business writing, stick to the point and say only as much as is necessary at the time. Keep paragraphs relatively short and easy to follow because letters are single-spaced. Long blocks of type can be daunting, and, as a consequence, the reader may skim the letter and miss your point.

In your final paragraph, state the response you are looking for. If a reply is required, ask for one. If you plan to do something as a follow-up, mention that. In the letter just shown, you might say, I would like to talk with you about this position and will call next week to arrange a time. Unless you have good reason to make a demand, phrase your requests politely, though, again, not so politely that the reader has no idea what you want. Include a deadline if it’s important. Once you’ve said what you need to say, end your letter.

If you’re on friendly terms with your correspondent, you might include a pleasantry or regards to a mutual acquaintance in closing, but neither should take up a large part of a business letter. Nor should you include anything that you or the recipient would feel uncomfortable allowing a co-worker or boss to see.

Whether you send your letter by post, fax, or e-mail will depend on factors such as urgency, etiquette, the need for review of your communication by others, and the expectations of your business. Some people do a major portion of their work online, while others seldom check their e-mail; if you’re not sure which category the recipient of your letter falls into, use postal mail. Some people think that if they fax a message, it will get quicker attention, and sometimes it does. But you don’t want to make a nuisance of yourself by faxing everything, whether it’s urgent or not; that’s a version of crying wolf. Again, as the technology of communication changes, so does the appropriate mode. Appropriateness, after all, is determined largely by what we’re used to.

Exercise 3–1 gives you a chance to practice writing different kinds of letters.

Exercise 3–1: Writing Letters

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Draft the body of letters for the following situations. Though letters will vary, compare yours with the samples at the end of the chapter for content, length, and tone.

Draft the body of letters for the following situations. Though letters will vary, compare yours with the samples at the end of the chapter for content, length, and tone.

1. You found out that your company has been “slammed,” a practice in which a telephone company takes over your account from the company you have chosen, usually without telling you. Slamming is not illegal in your state, but it is unethical, and, after you have returned to your original long distance provider, you are still angry. You know that the offices of state attorneys general forward complaints about slamming to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which keeps a record of which companies engage in the practice. Write a brief letter to your state attorney general’s office, registering your complaint.

2. The grocery delivery service you manage has just gone online. In the past, customers have consulted your catalogs and then ordered by phone or fax. Now, they can place their orders at your Web site—www.GroceriestoYou.xxx—and you will guarantee delivery within 15 hours. Orders placed online will be free, and as an added bonus, you’re offering $10 off the first order placed this way. Write a letter, no longer than three paragraphs, announcing this new opportunity to longtime customers.

3. At your new job as Acquisitions Editor of Lawton’s, a law textbook company, you have reviewed your list of titles and decided that several need updating. Write a letter introducing yourself and suggesting that the authors of these books get in touch with you if they are interested in doing more writing for your company. Though you will send the same letter to several authors, you will address each individually. This one is to Sibley Lawless, a professor of law. Keep it short and to the point, but be encouraging and friendly, since you hope that this will be the beginning of a fruitful relationship.

THE MEMORANDUM

The memo is the most common form of written communication within a company. It is used to:

• inform co-workers;

• announce policies, accomplishments, plans, and decisions;

• keep records of conversations;

• assign responsibilities;

• request information or responses; and

• instruct and motivate employees.

Memos are used by businesses to maintain records of all their actions. It’s not surprising, then, that clarity, accuracy, and appropriate tone are particularly important here.

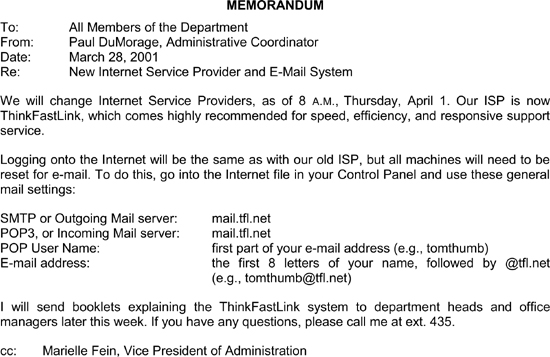

Protocol and Format

Memo style and format vary from company to company, so it is necessary to learn your company’s preferences. Most e-mail messages are set up as memos, making the format increasingly familiar. Exhibit 3–3 shows one standard memo format; however, the following points apply to all memos:

• In determining to whom you should address your memo, who receives copies, and he order of distribution, follow the protocol and hierarchy of your organization.

• Sign or initial the memo to show that you know of, have read, and approve of its contents. You can do this next to your typed name or at the end, depending on your company’s style.

• Make the title or subject description clear, accurate, and sufficiently detailed. It orients the reader and also determines how the memo is filed and retrieved. The title does not take the place of an opening sentence, however.

• In the title, capitalize the first letter of all words, except articles, prepositions, and conjunctions of fewer than four letters (e.g., and, but). However, if these are the first or last word, they should be capitalized.

• One- or two-page memos are usually single-spaced. Longer memos are prepared in manuscript format, that is, double-spaced. Again, follow the style of your company.

For the convenience of your readers, you may want to attach a routing list on top or provide a checklist at the bottom. For example:

I can meet on:

______Thursday, 21 April

______Friday, 22 April

______Tuesday, 26 April

Content

Though memos vary in length, they should be kept as short as possible relative to the complexity of your subject. Generally, a memo covers a single subject. Multiple-subject memos are harder to respond to and harder to file.

Memos may be used to persuade, analyze, inform, or argue for or against an idea or action. Regardless of their intent, they have certain basic things in common. First, memos begin with a statement of the central point. In many cases, this will be your solution to a problem or the conclusion you’ve reached through an analysis. If your readers are unfamiliar with the topic or its background, you will need to provide a brief review that includes only the information your readers need to understand the rest of your memo.

Even if your readers know the context, it’s a good idea to remind them of it: As we discussed when we spoke by phone yesterday. . . . This history is also important if your memo is to serve as a record. As we discussed in Chapter 2, there are times when you may not want to begin with your main idea. If you think your reader is going to be skeptical about what you have to say, or if you’re contradicting or disagreeing with a superior, a better strategy might be to begin by stating the problem, rather than your solution.

Regardless of where you begin in your argument or recommendation, the bulk of your memo will be devoted to persuading or convincing your reader. You accomplish this by means of logic and the systematic presentation of sound evidence to support your ideas, just as we discussed in Chapter 2.

Headings, lists, and charts help organize information both for you and your readers. Headings are particularly useful in long memos because they highlight main topics, break large chunks of information into manageable pieces, direct the eye and mind, and call attention to transitions. Lists, used with discretion, also highlight important material by making it stand out visually. They break up blocks of type and make priorities clear. Charts can make it easier to grasp relationships, numbers, or percentages. When you list ideas or items of information, or illustrate information in charts, be sure to connect them to the rest of the memo and make their significance explicit.

As in all writing, your tone must be appropriate to your audience and your purpose. A particular danger in a memo is to pare your writing down so much that it becomes curt to the point of rudeness. At the opposite end lies the danger of florid, stuffy, or pretentious writing. In this kind of self-important writing, people don’t ever get colds, but instead suffer from upper respiratory infections. Plain, clear writing is best. Strive for it. In Exercise 3–2, you can practice writing a memo with the right tone.

Exercise 3–2: Writing a Memo

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Write a memo to all employees in your division enlisting their help in cutting phone expenses by explaining what you want them to do in clear, measurable terms and an appropriate tone. Then compare your memo with the version at the end of the chapter.

Write a memo to all employees in your division enlisting their help in cutting phone expenses by explaining what you want them to do in clear, measurable terms and an appropriate tone. Then compare your memo with the version at the end of the chapter.

The situation: Telephone costs are one-third higher than last year, and though some of this difference is attributable to higher rates, you think it’s possible to keep phone bills within 15 percent of last year’s. As Services Manager of a small start-up company, you need to urge everyone in the company to keep telephone charges as low as possible, and you need to do it without raising hackles.

What you want from your readers:

• All sales orders, except for overnight deliveries, completed by postal mail, fax, or e-mail

• Greater use of discount rates during off-peak hours, especially to different time zones

• All overseas calls limited to 5 minutes

What you will do: Report on how well this works at the beginning of the next quarter.

THE PROPOSAL

The purpose of writing a business proposal is to persuade someone to pursue a course of action. It may be for internal or external use. An internal proposal usually is written by a subordinate to a superior, and its point usually is to recommend a change. An external proposal generally is written by a potential seller to convince a potential buyer to select the seller’s product or service. It will probably offer that product or service within a specified time at a specified price and may serve as a formal agreement.

Body of the Proposal

A proposal begins with an introduction whose main purpose is to summarize the problem or situation and the proposed solution. An introduction may also provide background information necessary for understanding the solution, and it may enumerate the benefits of the solution, as well as total costs. All this should be stated lucidly and directly, so the reader knows from the beginning what the writer is proposing.

Your business may prefer to put the conclusion or solution at the end of the proposal. If so, you’ll probably use what’s called an executive summary, which provides the same information as the introduction. (An executive summary may appear at the beginning of a proposal; again, it’s a matter of style.) A summary should be written in nontechnical language, and it should be separated from the body of the proposal or emphasized graphically to make it easy to identify.

The introduction or executive summary is followed by the body of the proposal, which may repeat the information that was summarized in the introduction. It should explain or describe:

• the scope of the problem you propose to solve,

• your reasons for selecting the solution,

• the benefits of the solution,

• the way the solution will be achieved,

• the method or organization to be used,

• the people responsible for carrying it out,

• a timeline, or beginning and ending dates, and

• a cost breakdown (this may be a budget amended to the proposal).

Before you begin your proposal, identify your goal and use that to guide the level of detail you provide. Consider these two different proposals and think about what details you would include:

1. You need to compare the merits of two trucking companies that the director of transportation is considering for a contract.

2. You want to suggest to the vice president for operations various ways to ship your widgets to the West Coast.

Each proposal would require its own set of details described to a different degree. If you were working at one of the trucking companies and writing a proposal to convince the widget company to hire you as its carrier, you would emphasize yet a third set of details.

As with all business communications, proposals are aimed at specific readers, so remember to tailor your writing to your readers, paying particular attention to their level of relevant knowledge. If you are writing about a complex subject or one that entails technical or obscure vocabulary, consider including a glossary or appendix to aid your reader.

A proposal ends with a conclusion in which the benefits of the recommendation are extolled and readers are called to action. Throughout the proposal, the tone should be confident, encouraging, and affirmative, but of course, that affirmation never should turn into bombast or unrealistic promises. The right tone is most important in the conclusion, which will create the final impression that readers take away with them. A good way to achieve the right tone is to be as specific and concrete as possible For example:

This symposium will correct misinformation and misunderstanding about OSHA regulations by examining five complaints filed in 1998 and analyzing their resolutions.

Proposals longer than one or two pages will probably be double-spaced, though this can vary, depending on how they’re printed, published, and circulated. In multiple-page proposals, you will probably need to organize your material under headings and perhaps subheadings for clarity and ease of reading. (A long, uninterrupted block of print is overwhelming and may obscure your point.) These divisions also help readers refer to specific points.

THE REPORT

Reports are similar to proposals: In both, you present information you’ve gathered, perhaps adding some analysis or insights. The major difference is that a report may be more neutral since, unlike a proposal, it does not necessarily seek to persuade or recommend an action.

The purpose of a report is to inform readers about achievements, activities, or issues. The material can be organized by topic, time sequence, comparison, or task. Usually, you would write a report for people at a similar or higher level than you in the organization, though it is likely to be read by a wider audience. Annual reports, for instance, are written for a company’s shareholders, but they are also available to the public and, therefore, are written and designed to create the public image a company desires. This influences their content and appearance.

Reports about current activities, such as trips or meetings, are usually short (one to four pages). Progress reports also may be short because they describe ongoing activities and work that has yet to be completed. Their format will be determined by your company, though reports over one or two pages are usually double-spaced, for ease in reading, and often use headings and lists for clarity.

Research and audit reports are usually longer, so they need an executive summary at the beginning. Research reports generally are written to provide information to high-level managers or executives. Their executive summaries include the purpose, scope, and findings of the research.

Audit reports also are aimed at executives. They report on a company’s compliance with internal or external financial regulations or on a company’s use of funds. They may be used to bring problems to an executive’s attention, so their conclusions may include recommendations along with the primary findings of the audit.

MINUTES OF A MEETING

Minutes are used to establish a record of what happens at a meeting. They note decisions taken, significant points of the discussion leading to these decisions, and matters to be considered at future meetings. They also serve as a record of who attended, spoke, and led the meeting. They are, essentially, a report on a meeting, and they are written in a reportorial style.

The degree of detail you will include will vary from business to business and meeting to meeting, so try to establish how extensive your minutes need to be beforehand. Minutes are not a complete transcription; tape recorders do that more efficiently than people. What people are good at is identifying and summarizing the main points, and that is what minutes are: a summary of significant events at a meeting. Minute taking, like other business writing, has been changed by technology. For example, voice-responsive programs are being developed, and a new system that can transcribe notes on a board directly to a computer will free minute takers to follow the gist of the discussion. That is important because, though minutes are primarily factual, minute taking is a skill, based on the art of listening.

Whole books have been written on how to listen, but for our purposes, let’s concentrate on listening for the main points. As a student taking notes in class, you probably learned to filter out the unimportant information—examples, anecdotes, jokes, digressions—and absorb the significant points. A good lecturer will help you do this by organizing his or her presentation and using words such as “first” or “therefore” to get the listener’s attention. Meetings are usually organized ahead of time too, and this organization is spelled out in an agenda. So the first thing to do when you’re taking minutes is to familiarize yourself with the agenda before the meeting begins. That way you’ll be able to anticipate the order of discussion and follow it more easily.

An important technique for identifying the main points in a discussion is summarizing mentally as you listen. Most people speak slower than your mind works, leaving you time to sift through what you hear and pull out the important material. This is especially true in meetings, where discussion may go on for some time before a conclusion or decision is reached. As you summarize:

• Listen for content, not style of presentation.

• Focus on ideas.

• Note outcomes more than processes.

• Condense ideas into brief phrases or sentences.

• Paraphrase unless the exact wording is significant.

Review your notes soon after the meeting is over—when everyone’s memory is freshest—to identify gaps or confusion, and check with others to ensure accuracy. Then write up your minutes clearly and without flourish. If you read them aloud at another meeting, you’ll find long, lyrical sentences hard to say and hard for listeners to follow. One final piece of advice: Make sure you spell all names correctly. It’s the bottom line of good minute taking.

WRITING TOGETHER

The preparation that leads up to the writing of proposals and reports, and sometimes memos, is frequently communal. Responsibility for researching or gathering information may be shared, and analyses and recommendations are usually reached by people working together to come to some conclusion. The writing itself may also involve more than one person, and this may require you to modify the way you write.

The points we keep emphasizing—know your audience, make your writing appropriate to their needs, organize your information, find good evidence, choose the right level of detail—apply whether you’re writing as a team or individually. We don’t recommend writing by committee—it’s cumbersome and time-consuming—but since it is not uncommon to share responsibility for a writing project, when you do, it’s a good idea to determine some ground rules ahead of time.

First, decide who will be responsible for what. You want to create a working relationship that capitalizes on each person’s strengths and expertise and leaves no significant gaps. Egos and hierarchies can get in the way of this, and people have different methods of writing, so agreeing on a method before you begin can make things go smoother. Here are some questions you’ll want to answer:

• Do you want to divide up primary responsibilities; for example, research and writing?

• Do you want to establish one person as the leader or editor, either for the whole project or for aspects of the project?

• Will each person be responsible for writing different sections, or will you write together? If the latter, be specific about how you’ll do this.

• How often will you consult with each other and review progress?

• Will you edit for consistency as you go along, or will you wait until the end?

• Who will be responsible for the final edit, and who will decide if there is disagreement?

Regardless of how you write it, you will want your proposal or report to read as if it came from one mind, so someone will need to edit for continuity of information, tone, and style. Also, mistakes are more likely to go undetected in shared writing, so make sure someone—preferably someone with a fresh perspective—proofreads the final version.

Most of your business writing will take the form of letters, memos, proposals, and reports, all of which rely on the principles of good, focused writing covered in Chapters 1 and 2. It is useful to be familiar with the standard formats for these types of writing and to identify your reader and your goals before you begin. You may also be called on to do other kinds of writing, such as taking minutes at a meeting. This requires listening for the main points and summarizing them clearly and accurately. Finally, some writing projects involve working with others. The writing task is the same, but sharing it demands some division of tasks and clear lines of responsibility.

Clear communication requires awareness of psychology and format, but it depends even more on putting the right words in the right order. The next three chapters will focus on those elements: writing effective sentences, putting them in order, and choosing the most appropriate words.

ANSWERS TO EXERCISES

Exercise 3–1

Sample Letter 1

Dear Attorney General:

I would like to register a complaint with your office about Susa Phone Company, since your office keeps a record of such complaints, which you forward to the FCC.

Last month, I discovered that Susa had taken over my long distance account from AnsaPhones, my phone service provider for the past five years. I was neither consulted nor notified about this change. I have since returned to AnsaPhones, but I do not believe this unethical practice should be allowed to continue. Please press for legislation that would make it illegal.

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

Sample Letter 2

Dear Ms. Broccoli:

As a longtime customer of Groceriesto You, you know that we offer name brand foods, the freshest produce and meats, and all your other grocery needs at supermarket prices—and we bring it all directly to your kitchen. Now we’ve made shopping with us even easier.

Simply shop on our new online grocery story at www.GroceriestoYou.xxx. Place your order, and receive your groceries within 15 hours; delivery is absolutely free. As an added bonus, when you take advantage of our new online ordering service within the next month, we’ll automatically deduct $10 from your first order.

Of course, you can also continue to shop from our catalogs by phone or fax and enjoy the same convenient service you always have. Either way, GroceriestoYou will keep saving you time and money.

Sample Letter 3

Dear Professor Lawless:

I am the new Acquisitions Editor for Lawton’s. Though this is my first acquaintance with the field of legal education, I’ve worked in acquisitions for commercial and academic publishers for the past decade.

Having just finished a review of our textbook series, I am impressed with its scope and quality. Over the years, many legal scholars and practitioners have contributed their expertise to build our internationally acclaimed list, and I feel fortunate to have inherited such a strong group of writers. Now I would like to focus on updating our core titles, building on established areas of interest, and enhancing our publications with software.

If you are interested in working with Lawton’s again—updating previous titles or adding new ones to our list—please let me hear from you. Call, write, e-mail—I’d love to talk with you about the latest developments in your field and hear about the areas you think we should pay attention to in the coming years. You are a vital link for us to the legal world. I look forward to hearing from you.

Sample Memo:

To: All Employees

From: Frank Chat, Services Manager

Date: July 30, 2000

Re: Telephone Expenses

You’ll probably be as surprised as I was to find that our telephone costs are a third higher than last year. Though some of this increase comes from higher rates, I think we can keep costs within 15 percent of last year’s by changing some of our telephone practices a little. I ask your help in meeting that goal.

Starting today, please make sure that you following these new policies:

• Complete all sales orders by e-mail, postal mail, or fax, except for overnight deliveries.

• Take advantage of discount rates by calling at off-peak hours whenever possible, especially to other time zones.

• Limit all overseas calls to 5 minutes.

Thanks for your assistance. I’ll report to you on how we’re doing at the beginning of the next quarter.

1. You are writing a letter to a product manager whose name you do not know. The best form of address would be: |

1. (c) |

(a) Dear Sir. |

|

(b) Hello Colleague. |

|

(c) Dear Product Manager. |

|

(d) to skip the greeting and go directly to the body of the letter. |

|

2. You should sign or initial your memo in order to: |

2. (a) |

(a) show that you know of its contents. |

|

(b) show that you typed it. |

|

(c) clarify your position in the organization. |

|

(d) make it easy to file under your name. |

|

3. A memo usually covers: |

3. (b) |

(a) recent developments. |

|

(b) a single subject. |

|

(c) three subjects. |

|

(d) the history of an organization. |

|

4. The purpose of an internal proposal usually is: |

4. (b) |

(a) to convince a potential buyer to select a product or service. |

|

(b) to recommend a change or improvement. |

|

(c) to discipline or commend a subordinate. |

|

(d) to organize an event or meeting. |

|

5. A proposal begins with a(n): |

5. (d) |

(a) salutation. |

|

(b) heading. |

|

(c) bibliography. |

|

(d) introduction. |

xhibit 3–1

xhibit 3–1

Review Questions

Review Questions