4

Effective Writing

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define and identify the three basic sentence patterns.

• Explain what a topic sentence is and what it does.

• Explain how to structure sentences to emphasize or deemphasize ideas.

• Demonstrate the use of parallel structure in sentences.

• Rewrite sentences to eliminate misplaced modifiers.

So far in this course, you have learned about focusing and organizing your ideas as you prepare to write, and you have reviewed the most common kinds of business writing. The next step is putting all this together to construct a message with the greatest clarity and impact. Because your primary building blocks are words, it is important that you choose them carefully so that each contributes to your meaning. You also need to structure your sentences logically so that the reader sees the points and connections you mean to make. These word choices and sentence structures are the substance of your writing style.

When you think of style in writing, you may think first of fiction, where style is a distinguishing element. How a story is told may be as significant as what is told, so we are often delighted when fiction writers use meandering sentences, obscure vocabulary, and images that make us stop in our tracks. We are less charmed when we encounter these traits in business communication, but style matters here, too, because style and content are interrelated.

In writing for business, your goal is to communicate clearly. You don’t want your readers to have to reread a sentence or stop to look up words in the dictionary—or worse, not reread or look up the words, so that they fail to understand what you’re trying to say. An easy-to-read style will help avoid these problems.

This chapter offers specific techniques for constructing sentences that convey your meaning clearly. In combination with the following three chapters, it will show you how to develop an appropriate and effective business writing style.

CHOOSING APPROPRIATE SENTENCE PATTERNS

Just as a carpenter might use different sizes of beams and boards in building a house, you need to use different kinds of sentences to construct a piece of writing. In this chapter, you’ll learn about the three main types of sentences. Each serves a different purpose.

Sentences are made up of clauses, groups of words containing at least a subject and a verb. There are two types of clauses: a main clause, which is the principal part of the sentence and can stand alone as a sentence, and a subordinate clause, which is dependent on the main clause and cannot stand on its own.

Clauses that are lopped off from sentences and left hanging are called sentence fragments. You may find them punctuated as if they were sentences, but they’re really poor relations and they’re incorrect.

Simple Sentences

A simple sentence consists of one main clause—a subject and a verb. Because a simple sentence conveys a single idea, it is a good choice for emphasizing a central point; for example, We have a new order form for office supplies.

Compound Sentences

A compound sentence contains two or more main clauses, each of which could be a sentence by itself. It shows relationships between two or more ideas or things, which are sometimes in opposition to each other; for example, I want to help you complete the report, but I have to be on a plane to Phoenix at 4:00 this afternoon.

In this sentence, the ideas expressed are related and of equal importance, two essential elements in a compound sentence. Unless you mean to point out incongruity, try not to join unrelated ideas, as in, I want to help you complete the report, and I can’t wait to sit on the beach for my vacation.

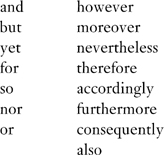

When you have two main clauses in a sentence, because the ideas are equal in importance or rank, you need to use a connecting word, such as:

Use a comma to set off the connecting words in the left-hand list. With those in the right-hand list, use a semicolon before the connecting word and a comma after it:

We love good food, and we eat out often. We love to cook good food; nevertheless,

we eat out often.

Complex Sentences

A complex sentence contains one main clause and one or more subordinate clauses, all related (1) in a time sequence, (2) as cause and effect, (3) as an action leading to a purpose or result, or (4) by some condition. The ideas expressed in a complex sentence generally are unequal in importance. The sentence shows a connection between the less important idea and the main idea:

The company demanded immediate replacements for our forklift trucks because the

service manager complained about smoke and odor from them.

The most important information in this sentence is that the company has demanded replacements, so that idea is placed in the main clause, which could stand alone as a sentence. The word because shows that the relationship between the two clauses is cause and effect. Notice also that the second clause, because the service manager complained about smoke and odor from them, cannot stand alone as a sentence because it is not a complete thought.

The following examples demonstrate how placement of the main idea influences the meaning and emphasis in a sentence:

• We visited the Tyne Corporation’s service manager after he complained about the trucks. (time)

• Because Tyne’s service manager was unhappy, we sent one of our trouble-shooters to visit him. (cause or reason)

• We wanted to solve the problem so that we could restore a good working relationship with Tyne. (purpose or result)

• I spoke only to the service manager at Tyne, although the operations chief was available. (condition)

The position of clauses also dictates the correct punctuation. If the main idea comes last, a comma separates the two ideas: Because the tuna fishing industry had a disastrous year, the Sorry Charlie Company went belly up. However, if the main idea comes first, no separating comma is needed: The Sorry Charlie Company went belly up because the tuna fishing industry had a disastrous year. When the less important idea comes in the middle of the sentence, it must be set off by commas: In 1993, a disastrous year for the tuna fishing industry, the Sorry Charlie Company went belly up.

Sentence Choices

To select the sentence pattern that best conveys your meaning, you have three main choices:

A simple sentence with one main clause: We goofed.

A compound sentence with two or more closely related, equally important ideas, each stated in a main clause. Main clauses are often joined by but, and, or or: We goofed, and we’re sorry.

A complex sentence with two or more closely related, but not equally important ideas, one of which is stated in a main clause. The relationship between main and subordinate clauses is expressed by a connecting word: Since we goofed, we’ve been apologizing continuously.

The subordinate idea in this example—a disastrous year for the tuna fishing industry—adds a defining characteristic to the term it modifies: 1993. In your sentences, aim to keep the less important idea as close as possible to the word or words it explains. The alternative can be fuzzier and weaker: In 1993, the Sorry Charlie Company went belly up because it was a bad year for the tuna industry.

These variations on a tuna demonstrate two rules for complex sentences:

1. Commas set off the less important idea.

2. The less important idea follows the word or words it explains.

Exhibit 4–1 summarizes possible choices in sentence patterns.

USING SENTENCES EFFECTIVELY

When you write, you combine sentences into paragraphs as a way of organizing your thoughts. A coherent paragraph begins with a topic sentence. When you move from one thought to another, usually indicated by a paragraph break, you use transitional words or phrases to guide the reader.

Topic Sentences

A topic sentence previews or summarizes the main ideas presented in a paragraph. It serves as a guidepost and is a favorite of readers who skim because it allows them to pick out key ideas easily. It also helps you, the writer, keep your focus because a topic sentence is similar to a main heading in an outline. Both can remind you what you’re writing about. Here is an example of a paragraph with a strong topic sentence, which introduces the ideas that follow:

The federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) defines one type of sexual harassment as gender discrimination. This is discrimination against women because they are women. This category covers such clearly discriminatory acts as assault, threats, unwanted touching, and quid pro quo bargains. Most antidiscriminatory law is based on the EEOC guidelines, so this category figures prominently in workplace antisexual harassment policies.

Paragraphs

After you highlight your key idea in a topic sentence, develop the rest of the paragraph by offering additional information or analysis to support that idea. There are several possible organizational tools for expanding on the topic sentence, including:

• providing facts, examples, or a chronology,

• comparing or contrasting ideas or methods,

• narrating a sequence of events, and

• arguing a position or proposal.

Choose the type of organization most suitable to your topic. For example, if you want to describe the background of a proposal, it makes sense to trace the history of the subject through a chronology. If your purpose is to urge one course of action over another, a comparison of benefits and costs is probably your best bet. To review organizational designs, refer to Chapter 2.

In general, it is desirable to devote one paragraph to each major idea, though some ideas will require a few paragraphs to develop and others will be so closely related that they will need to be presented together for the sake of clarity and logic.

Transitions

Transitions— words or phrases that suggest relationships between ideas—smooth the shift from one concept, sentence, or paragraph to another. Transitions usually come at the beginning of sentences or paragraphs and refer to what came before. There are several types:

• Modifying words, such as thus, moreover, nonetheless, therefore, consequently, however, and also.

• Phrases, such as in addition, in summary, in contrast, as a result, in conclusion, and for example.

• Pronouns, which always provide transition by referring to the words they modify. (For example, if you ended a paragraph about a new inventory system by writing, Callie summed up the impact it would have on us, then you could make a smooth transition by beginning the next paragraph: It was she who had recognized the need to change it late last year)

• Key words that are repeated.

• Numbering or sequence words, such as first, before, next, afterward, last, and finally.

Transitions are useful tools when used appropriately and moderately. Use them when they seem natural to the flow of your writing and will help the reader understand the connections among your ideas. If a transition serves neither purpose, omit it. You may find that you need fewer transitions to guide your readers than you think.

In Exercise 4–1, you can practice organizing sentences into a logical sequence.

Exercise 4–1: Organizing Sentences

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Organize the following sentences into the most logical and coherent sequence for a paragraph.

Organize the following sentences into the most logical and coherent sequence for a paragraph.

1. The book will also discuss controversies in the workplace.

2. Finally, it will serve as a useful reference.

3. As in earlier versions, the revised text will provide explanations, examples, exhibits, and exercises.

4. How to Succeed at Success offers guidelines for a successful business career.

5. These are intended to stimulate the kind of thinking managers are called on to do.

EMPHASIZING AND DEEMPHASIZING IDEAS

Your knowledge of the three basic sentence patterns will help you emphasize and deemphasize ideas and information. The following sentences contain most of the same words, yet their meanings vary. Think about why that is so.

1. We recently filled the assistant manager’s job that Ms. Bright wanted.

2. Ms. Bright had wanted the assistant manager’s job that was recently filled.

3. The assistant manager’s job is the one Ms. Bright wanted, but we filled that position recently.

4. Ms. Bright wanted the assistant manager’s job; however, we filled it recently.

These sentences are all grammatically correct and similar in content. Yet they emphasize different aspects of the same situation: either the filling of the job or Ms. Bright’s desire for it.

The first sentence emphasizes that the job was filled. It does this by putting that idea in a main clause that could stand alone as a sentence: We recently filled the assistant manager’s job. This sentence deemphasizes the person’s desire for the job by putting that idea in the subordinate clause.

Emphasizing Ideas

To emphasize an idea:

• put it in a main clause,

• place it at the beginning or end of the sentence, and

• make it the subject of the sentence.

To deemphasize an idea:

• put it in the subordinate clause,

• place it in the middle of the sentence, and

• don’t make it the subject of the sentence.

The second sentence has the opposite emphasis. The person’s desire for the job is emphasized by putting it in the main clause (Ms. Bright had wanted the assistant manager’s job), whereas the filling of the job is deemphasized by putting it in the subordinate clause.

The third sentence emphasizes that it was the assistant manager’s job, as opposed to another job, that Ms. Bright wanted. We know this because the phrase the assistant manager’s job is the subject of the sentence and appears at the beginning.

Finally, the fourth sentence puts equal emphasis on Ms. Bright’s desire for the job and the filling of the job by stating both ideas in main clauses joined by a semicolon. Exhibit 4–2 summarizes the relationship between emphasis and sentence design.

When you have a crucial or subtle idea to convey, try phrasing it different ways and then choose the one that emphasizes the most important aspect of your idea. Be careful not to emphasize the lesser ideas and bury the more important ones, as in the sentence, The government conducted a study and found that only 10 percent of Americans believe IRS forms are easy to complete. Here, the point of the sentence—Americans’ difficulty with IRS forms—is neither placed first nor made part of the main clause. This problem arises from a particular way of thinking. We tend to set the stage first by citing the actor: the government. Then we proceed to the action, conducted a study and found. We get to the point, the problem, only at the end.

The sentence as written is a good choice only if you want to emphasize that it is the government, rather than some private group, that conducted the study. But, more likely, it is the result of the study that is significant. The sentence should be rewritten to put the main idea first and in the main clause: Only 10 percent of Americans believe IRS forms are easy to complete, according to a government study.

But what if you want to emphasize two or more ideas equally? You have two options: You can put them in equally important clauses, or you can put each in a separate sentence.

When joining main clauses, be sure to use a connecting word (e.g., and, or, but) preceded by a comma. Never use a comma without a connector; that creates what’s known to grammarians as a comma splice. In case you don’t remember that sin from school days, here’s a good example of a bad sentence: We begin our telemarketing campaign next week, we expect a good response. You have four ways to correct that sentence. Try to rewrite it correctly in Exercise 4–2.

Exercise 4–2: Beware the Dreaded Comma Splice

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Rewrite the following sentence correctly in four different ways. You may have to add a transitional word, but keep the meaning the same.

Rewrite the following sentence correctly in four different ways. You may have to add a transitional word, but keep the meaning the same.

We begin our telemarketing campaign next week, we expect a good response.

1. _________________________________________________________________

2. _________________________________________________________________

3. _________________________________________________________________

4._________________________________________________________________

When joining more than two ideas, you must be especially careful that the ideas are, in fact, equally important. If they aren’t, use connecting words that show relationships clearly and guide your reader from idea to idea. That is much better than stringing together a series of short, choppy sentences that don’t relate clearly to one another. It’s better, too, than giving a subordinate idea its own sentence or main clause, which, because of its isolation, calls too much attention to the idea.

Words or ideas placed at the beginning or end of a sentence are generally the most prominent. When an element other than the subject comes first, it becomes emphatic. For instance, Clarity is the business of writers.

Putting a word or group of words at the end of a sentence for emphasis works particularly well when you want to introduce a new element or idea. This is illustrated by Robert Frost’s observation: “A jury consists of twelve persons chosen to decide who has the better lawyer.”

This principle—placement at the beginning or end of a sentence emphasizes a word—also applies to sentences in a paragraph and paragraphs in a message, as we shall see in later chapters. Exercise 4–3 will let you practice using sentence structure to emphasize an idea.

Exercise 4–3: Structuring for Emphasis

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Rewrite the following sentence to emphasize each idea listed on the next page.

Rewrite the following sentence to emphasize each idea listed on the next page.

Moral rights, a legal concept, are an aspect of copyright that give creative artists

control over the integrity of their work.

1. the legal issue:________________________________________________

2. what copyright includes:_________________________________________

3. who benefits:_________________________________________________

CONTROLLING SENTENCE LENGTH

Now that you have learned about the major sentence patterns and the relationships among the parts of a sentence, you need to think about sentence length. A sentence is a unit of thought. The longer the sentence, the more ideas a reader must keep in mind at the same time. If too many ideas come at once, the reader may lose control over some or forget them all. Try rewriting an overly long sentence more clearly in Exercise 4–4.

Exercise 4–4: Sentence Length

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() In the following paragraph, all 63 of the words are simple and familiar, but when they’re strung together in one sentence, they’re daunting. Rewrite the sentence as four sentences, aiming for clarity. Compare your revision to the one suggested at the end of the chapter.

In the following paragraph, all 63 of the words are simple and familiar, but when they’re strung together in one sentence, they’re daunting. Rewrite the sentence as four sentences, aiming for clarity. Compare your revision to the one suggested at the end of the chapter.

Sufficient demand exists to support the proposed addition of 100 to 120 guest rooms to the hotel, along with either a new food and beverage facility, plus several meeting rooms, or a conference center with facilities for 600 to 800 people, believing that, regardless of the size and purpose of the expansion, a new pool will be necessary to meet the increased demand.

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

One important way to make your writing easy for readers to understand is to keep the sentences reasonably short. What’s short? According to Rudolf Flesch, an expert on measuring reading levels, an average of 11 to 15 words in a sentence makes for fairly easy reading. This applies when your words are short and common, but, even when you’re writing about a technical topic, your goal should be an average sentence length of fewer than 20 words. (Word processing programs will make this calculation for you, but you can figure the average sentence length in a piece of your writing by dividing the total number of words by the total number of sentences.)

This doesn’t mean that an average sentence length of six to nine words is even better, though. A series of short sentences can be almost as bad as a series of long sentences, as we’re about to see. Moreover, if you stick to short sentences only, you may omit important connecting words, such as however and since, which show relationships and improve the ease of reading.

CREATING RHYTHM WITH SENTENCE VARIETY

Relying on a string of simple sentences may make for clear and concise writing, but it can also make your writing seem simplistic, choppy, angry, or monotonous. Consider the following example:

We must do something about our management-trainee program. Our current method of recruitment is ineffective. We haven’t filled a trainee class in three years. We don’t have adequate information to tell us why. All we have is speculation. We need to fill the class this year. It doesn’t look like we’re going to. We need to study successful programs. That will tell us what we’re doing wrong.

It sounds like a first-grade reader, doesn’t it? It isn’t all that easy to follow, either, because no connections are made between ideas. Yet pairing the sentences to turn them into a series of compound sentences isn’t much better:

We must do something about our management-trainee program, and we have to redesign our recruitment. Our current method is ineffective, and we haven’t filled a trainee class in three years. We don’t have adequate information to tell us why, and all we have is speculation. We need to fill the class this year, but it doesn’t look like we’re going to. We need to study successful programs, and that will tell us what we’re doing wrong.

Yawn. The rhythm is singsong, making the ideas seem trite. We could rewrite the piece as a series of complex sentences, but that would be only marginally better. So what’s the alternative?

The trick to creating fluid and interesting writing is varying the kinds of sentences you use: some short and punchy, others longer and more intricate; some joining two clauses with a colon, others starting with dependent clauses or transitional phrases. Other techniques for varying sentence structure include inverting the normal word order (e.g., Particularly important is the emphasis on self-sufficiency) and asking questions that you proceed to answer (e.g., What can be done to achieve these goals?).

By mixing types of sentences, you create a rhythm that encourages the reader to follow your train of thought. Variety in sentence structure, length, and rhythm also represents the true relations among thoughts more accurately than a series of similar sentences will. So a more engaging way to write about the recruitment problem might be:

In order to improve our management-trainee program, we must change our recruitment methods. Our trainee class hasn’t filled in three years, nor does it look like it will this year. Yet we have only speculation to explain why this is so. We need more information, and we need to examine the problem methodically. I recommend that we study successful programs—those that routinely receive more applicants than they can accept—to learn what they’re doing right and what we’re doing wrong.

BUILDING SOUND SENTENCES

Techniques such as varying sentence structure for emphasis and clarity will help your writing style, but unless your sentences are sound to begin with, you’ll be building a house of cards. To construct solid sentences, you need to use parallel structure and you need to place your modifiers correctly

Parallel Structure

As we discussed earlier, one way to show that ideas are equally important is to put them in equal parts of the sentence. These equal parts may be clauses, phrases, verbs, nouns, or another part of speech. In other words, a series of equally important items in a sentence should be presented in parallel form. This fundamental technique is called parallel structure. Parallel structure requires that the items in the series have the same grammatical form. They might all be verbs:

She marshaled her evidence, spoke eloquently, and convinced the audience.

Or nouns:

Education, work experience, and references are what we consider in hiring.

Or phrases:

We hope our product will appeal to teenagers, who call it retro, and to adults, who call it nostalgia.

Or clauses:

I want to start the project at once, my boss wants to wait, and the board of directors wants to cancel it completely.

These are all examples of well-constructed sentences using parallel structure. In contrast, the following sentence is awkward because it mixes different grammatical forms: The purposes of the focus group are to determine what consumers think of this new product, evaluation of their attitudes toward the product category, and recommending appropriate action. Exercise 4–5 allows you to practice creating parallel structure.

Exercise 4–5: Parallel Structure

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Revise the following sentences to create parallel structure. Then compare your revisions to those at the end of the chapter.

Revise the following sentences to create parallel structure. Then compare your revisions to those at the end of the chapter.

1. Tell us what color you want the office painted, the furniture arrangement, and where to put the paintings.

______________________________________________________________

2. I’ll need the following items for the meeting: notepads, how participants will be seated, to be able to project charts, and working with someone on the agenda.

______________________________________________________________

3. Public presentations and to be available for travel are both parts of the job.

______________________________________________________________

4. The client insisted on reviewing the proposal and a discount.

______________________________________________________________

Parallel structure is advisable, but it doesn’t work in every case. It can’t be used when the items in a series are of unequal importance; for example: He attended PS 163 in Brooklyn, was elected to Congress from Connecticut in 1989, and received his party’s nomination for president last year. The first item is far less important than the others, so it is out of place in this sequence. It could be saved for another part of the message, but it doesn’t belong here.

Nor should parallel structure be used when items in a series are significantly different in quality or kind, as in, Sheila has beauty, brilliance, and a cocker spaniel. The items in this list of attributes are the same grammatically (all nouns) but very different conceptually. So, unless your intent is humor, unleash the cocker spaniel in another sentence.

Similarly, if the items in a series are not conceptually parallel, parallel structure doesn’t work; for instance, Ernie would bring three skills to this job: mathematical ability, ease with customers, and Spanish. The last item doesn’t fit because it is a language, not a skill. Changing it to fluency in Spanish would correct the problem and the sentence.

To punctuate the items in a series, use a comma after each item when there are three or more; for example, The three most important things in real estate are location, location, and location. Some writers omit the final comma before the conjunction (and), but including it is never wrong and helps separate the last two items.

A colon may be used before a list of items to mean note what follows; for example, Our offices are located in each of our sales regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West. Use a colon only after a main clause. It is incorrect elsewhere, such as between a verb and its object or between a preposition and its object. Our sales territories are: the Northwest, Midwest, South, and West is wrong because it separates the verb (are) from its object (the Northwest, Midwest, South, and West).

Headings, too, benefit from the use of parallel structure. Note that the headings in this chapter all begin with a participle: choosing, using, emphasizing, controlling creating and building. They are parallel because they are similar in grammatical structure and intention. Exhibit 4–3 summarizes when to use parallel structure and how to punctuate it.

Misplaced Modifiers

English, like all languages, has its complexities. The same word can mean different things depending on its context and position in a sentence. To reduce ambiguity and other forms of confusion in your writing, you need to be attuned to the many pitfalls in the language. Primary among these are misplaced modifiers. A modifier is a word, phrase, or clause that limits or qualifies the meaning of another word. Adjectives and adverbs are common modifiers.

A modifier is misplaced when it seems to apply to the wrong part of a sentence or when the reader cannot tell which part of the sentence the modifier does apply to. Sometimes a misplaced modifier is merely awkward; other times it’s fanny. Funny’s fine, but only when you intend to be. A single sentence should make our point clear: Our office received a letter from a client covered with exotic stamps.

The best way to avoid gaffes and confusion is to keep modifiers close to the words they modify. Adjectives should precede their nouns, and adverbs should follow their verbs as closely as possible.

The large group of trainees had difficulty hearing the speaker.

Not: The large trainee group had difficulty hearing the speaker.

Subordinate clauses should come next to the word(s) to which they refer.

Studies show that salespeople who show enthusiasm increase their sales.

Not: Studies show that salespeople increase their sales showing enthusiasm.

Limiting modifiers, such as almost, even, and only, should immediately precede the expressions they modify.

They saw each other only during meetings.

Not: They only saw each other during meetings. (This is ambiguous. Does it mean that they met only at meetings or that during meetings, they had eyes only for each other?)

Keep subjects and their verbs close together and, if possible, avoid sticking a phrase between them.

On examining the necklace closely, the appraiser found an inscription in Arabic.

Not: The appraiser, on examining the necklace closely, discovered an inscription in Arabic.

Dangling Modifiers

When a word or phrase is meant as a modifier but doesn’t actually modify anything in a sentence, it is called a dangling modifier. Readers usually can figure out what sentences marred by dangling modifiers intend to say, but they really say something quite illogical. The following are examples of common types of dangling modifiers:

Walking down the street, the bus sped by me. (The bus walked down the street?)

To finish on schedule, overtime kicked in. (Overtime had to finish on schedule?)

On waking up, coffee was the first thing Ben craved. (Coffee woke up?)

Being a manager, it is important for me to write clearly. (It is a manager?)

Words came easily while addressing the admiring crowd. (Words addressed the crowd?)

Though dangling modifiers most often appear at the beginning of sentences, they also can come at the end, as in the final example. The way to avoid dangling your modifiers is to revise the sentence, either by changing the subject of the main clause or by rewriting the dangling modifier as a complete clause. Try your hand at undangling those modifiers in Exercise 4–6.

Exercise 4–6: Avoiding Dangling Modifiers

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Rewrite each of the following five sentences to eliminate the dangling modifier, then compare your revision to those at the end of the chapter.

Rewrite each of the following five sentences to eliminate the dangling modifier, then compare your revision to those at the end of the chapter.

1. Walking down the street, the bus sped by me.

______________________________________________________________

2. To finish on schedule, overtime kicked in.

______________________________________________________________

3. On waking up, coffee was the first thing Ben craved.

______________________________________________________________

4. Being a manager, it is important for me to write clearly.

______________________________________________________________

5. Words came easily while addressing the admiring crowd.

______________________________________________________________

Think of your sentences as the essential building blocks of your writing, and try to eliminate the weak elements. Sentences can be weak in many ways. They can be the wrong length, have inappropriate emphasis, lack parallel structure, or include misplaced or dangling modifiers. If you understand the way sentences are formed, if you think of them as logical expressions of thought, and if you keep appropriate structure in mind as you write, you can formulate your message in a way that will be easy for your readers to understand.

ANSWERS TO EXERCISES

Exercise 4–1

Order of sentences: 4, 3, 5, 1, 2

Exercise 4–2

Suggested revision:

1. We begin our telemarketing campaign next week, and we expect a good response.

2. When our telemarketing campaign begins next week, we expect a good response.

3. Our telemarketing campaign begins next week; we expect a good response.

4. Our telemarketing campaign begins next week. We expect a good response.

Exercise 4–3

Suggested revision:

1. As a legal concept, moral rights are an aspect of copyright that gives creative artists control over the integrity of their work.

2. Copyright encompasses moral rights, a legal concept that gives creative artists control over the integrity of their work.

3. Creative artists are given control over the integrity of their work through moral rights, a legal concept that is an aspect of copyright.

Exercise 4–4

Suggested revision:

Demand for our facilities has been increasing. We should add a new pool and 100 to 120 guest rooms to the hotel. We also recommend adding a new food facility and meeting rooms or a new conference center. These should accommodate 600 to 800 people.

Exercise 4–5

Suggested revision:

1. Tell us what color you want the office painted, how you want the furniture arranged, and where you want the paintings hung.

2. I’ll need the following items for the meeting: notepads, a seating plan, and an overhead projector. I’ll also need someone to help me create the agenda.

3. Being able to make public presentations and being available for travel are both parts of the job.

4. The client insisted on reviewing the proposal and demanded a discount.

Exercise 4–6

Suggested revision:

1. As I walked down the street, the bus sped by me.

2. Overtime kicked in as we tried to finish on schedule.

3. The first thing Ben craved when he woke up was coffee.

4. It is important for me as a manager to write clearly.

5. Words came easily to the speaker as he (or she) addressed the admiring crowd. Or, Words came easily to me as I addressed the admiring crowd.

xhibit 4–1

xhibit 4–1

Review Questions

Review Questions