7

Direct and Forceful Writing

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Name three techniques to make your writing powerful and precise.

• Cite three reasons for using active rather than passive verbs in writing.

• List and illustrate three appropriate uses of passive verbs.

• Define concrete nouns and abstract nouns.

• Change nouns that are hidden verbs into active verbs.

Straightforwardness is a hallmark of American English. We like to call a spade a spade, rather than a gardening implement, and we admire people who speak their minds without putting on airs. Direct, unadorned writing has characterized much of American literature, journalism, and letter writing throughout our history, but business writing seems to have escaped this impulse to pare down. What are we to make of this example, a memo written by a bank executive?

A detailed knowledge relative to problem areas and approaches to their solutions has been accumulated, with the result that advanced activity programming by individuals in middle and top management positions, and the latter in particular, prior to a promotion situation or their initial assumption of their new responsibilities, is indicated and in fact recommended.

The writer is recommending that top-level managers do something (it’s unclear what) because someone (it’s unclear who) has detailed knowledge about rather vague problems and solutions. It took 54 words to confuse readers thoroughly, if they bothered reading at all.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to avoid obscure writing by relying on the primary building blocks of sentences: nouns and verbs. You’ll be introduced to three techniques that will make all of your writing more powerful and precise:

• Using active verbs

• Using specific, concrete nouns

• Avoiding tired language

USING ACTIVE VERBS

You may have heard the admonition to use active verbs or, as it is sometimes phrased, to use the active voice. Active verbs are important in business writing because they:

• give your writing energy and punch,

• usually create shorter sentences, and

• help prevent misunderstandings.

Before you can add active verbs to your writing, you must know what active verbs are. Let’s begin with the differences between these two sentences.

The Flat Earth Company bought this properly.

This property was bought by the Flat Earth Company.

Two obvious differences are length and emphasis. Using two fewer words, the first sentence stresses that the Flat Earth Company and not some other company bought the property. The second sentence emphasizes that the Flat Earth Company bought this property and not some other property. Depending on what you intend to emphasize, both sentences are effective. Let’s take them apart to see how to make your sentences do what you want them to do.

All sentences must have at least a subject and a verb, and many contain direct objects as well. These parts carry the weight of the meaning. In the first sentence, Flat Earth Company is the subject, that is, the main noun or pronoun about which something is being said. Bought is the verb, the word that expresses an action or state of being. This property is the direct object, the thing that was acted upon—in this case, bought. In the first sentence, the subject (Flat Earth Company) performed the action that the verb expresses (buying). This kind of verb is called an active verb.

In the second sentence, the opposite is true. The subject is property, and the verb is was bought. (There is no direct object.) So here the subject did not perform the action the verb expresses. This kind of verb is called a passive verb. Only in a prepositional phrase (by the Flat Earth Company) do we find out who or what performed the action.

To identify an active verb, ask yourself, Does the subject perform the action the verb expresses? If the answer is yes, the verb is active; if the answer is no, the verb is passive.

In the sentence, Verbs R Us declared bankruptcy, did Verbs R Us do the declaring? Yes; therefore, the verb is active.

In the sentence, Bankruptcy was declared by Verbs R Us, did bankruptcy do the declaring? No; therefore, the verb is passive.

Writers who seek to engage readers are well aware that active verbs are livelier and more compelling than passive ones. Passages that rely on active verbs also tend to flow better and have greater variety in sentence structure and rhythm. These benefits are apparent in the following advertising copy that appeared in a guide to Kentucky’s state parks. Notice how the active verbs, the ones in italics, carry the meaning and give the writing energy.

Daniel Boone and his company reached the Kentucky River on April 1, 1775, and commenced laying out Kentucky’s second settlement. Today Fort Boonesborough has been painstakingly reconstructed and offers visitors a chance to walk back in time to experience early pioneer life. Resident artisans demonstrate their skills on functioning antiques from the 18th century, and the park’s museum tells the story of Daniel Boone and the settlement of the area. Fort Boonesborough also features a natural sand beach and river boat rides on the Shawnee Chief.

Sentences using active verbs are usually shorter because passive verbs require helping verbs. The following pairs of sentences mean approximately the same thing, but look at the difference in wordiness:

Sentences with passive verbs are also wordier because they may need an extra phrase to show who is responsible for the action:

The decision to require the meetings to be attended by all programmers was made by the project manager. (19 words)

The project manager decided to require all programmers to attend the meetings. (13 words)

Perhaps the greatest advantage of active verbs is that they help prevent misunderstandings because they make it clear who is responsible for an action. Suppose you receive a memo containing this passive sentence:

The manual is now being revised by the operations department, and the staff report will be completed by May.

We learn that the operations department is responsible for revising the manual, but who is responsible for completing the staff report? The operations department? Maybe. You? Maybe. Some other person or group? Maybe. You won’t find out from the sentence as it’s written. If it were recast in the active voice, the meaning would be clear. You have a few options:

The operations department is now revising the manual and will complete the staff report by May.

The operations department is now revising the manual, and the personnel department will complete the staff report by May.

The operations department is now revising the manual, and you should complete the staff report by May.

The consequences of confusion over who is supposed to do something can be serious. Suppose you write to your boss, Arrangements should be made for antivirus software to be provided by Information Services. You send a copy to Information Services, and the fun begins.

Your sentence could mean that Information Services should make the arrangements, but Information Services could interpret it to mean that your boss should make the arrangements, and your boss could understand that you will take care of the arrangements. The upshot might be that no one makes arrangements and computers crash, or that everyone does the same thing, gets in one another’s way, and wastes time and money. The source of the misunderstanding is the vague, passive phrase arrangements should be made. You need to say who will make them and use an active verb.

Sometimes the confusion created by vague, passive sentences is intentional. Bureaucratese abounds with passive constructions, such as, “A confusion has happened and mistakes were made.” This is a cagey way of navigating an explosive situation without taking responsibility or placing blame. Something’s happening out there, says the passive voice, but we’re innocent; or, There’s this idea floating around, but I certainly won’t claim it as mine.

Ask yourself the point of this kind of namby-pamby writing. For instance, what is gained by writing, It is felt that a good suggestion has been made? You usually don’t need to fall back on such indirection. In fact, substituting an active verb makes the sentence, and the writer, sound more intelligent and resolute: I think your suggestion is good. Or, if more directness is appropriate to the situation, you can eliminate I think, since the reader understands that it is your opinion. The sentence then becomes short, direct, and strong. Your suggestion is good.

You may be inclined to use the passive voice when writing about technical or scientific subjects. Some people mistakenly believe that passive writing is objective writing because it appears to eliminate references to the writer and, therefore, his or her biases or opinions. Sometimes you will want to emphasize the thing being acted upon rather than the person performing the action. But even then, the majority of your sentences should use active verbs so that your writing is crisp, clear, and concise.

Making Passive Sentences Active

You have a few options for making a passive sentence into an active one. Suppose you write about your company’s product: When an application of Glide-On Paint is made to this surface, it is protected from rust. If you were writing instructions for painters, you could make you the subject and change the verbs to their active forms:

By painting this surface with Glide-On Paint, you can protect it from rust.

If you were writing a product research report, you would want to deem-phasize the people involved and stress the paint’s quality, so you’d use the verb protects and rewrite the sentence as:

Painting a surface with Glide-On Paint protects it from rust.

Here is another example of how a passive sentence becomes active. Imagine that you are an auditor and write, In the audit that was done, it was found that important facts had been omitted from accounts receivable records. You use a passive verb to avoid mentioning yourself or implicating others in questionable bookkeeping. You could get around that awkwardness and keep the sentence active by making the members of your firm the subject:

In the audit, we found that important facts had been omitted from accounts receivable records.

But the audit, not the auditors, really should be the star of the sentence. Both of the following sentences emphasize the findings of the audit rather than the people involved and still use active verbs.

The audit revealed that the accounts receivable records omit important facts. The accounts receivable records omit important facts, according to the audit.

Sometimes writers shift unnecessarily from active verbs to passive verbs in the same sentence. Parallel structure requires that both verbs be the same, and strong writing requires that both be active. So the following sentence needs a change in its second clause: Because he knew [active verb] that the ability to speak well in front of a group is important, a class in public speaking was taken [passive verb] by him. A good revision would be Because he knew [active verb] that the ability to speak well in front of a group is important, he took [active verb] a class in public speaking. You wouldn’t want to change both verbs to their passive form because a series of passive verbs makes the writing weak and awkward.

Exercise 7–1 gives you a gem of an opportunity to practice changing passive verbs to active ones.

Exercise 7–1: The Active Voice

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() In the following paragraph, nearly every verb is passive. Rewrite it so that it relies primarily on active verbs, then compare your sparkling version with the one at the end of the chapter. Also, count your words and see how the number compares with the suggested version.

In the following paragraph, nearly every verb is passive. Rewrite it so that it relies primarily on active verbs, then compare your sparkling version with the one at the end of the chapter. Also, count your words and see how the number compares with the suggested version.

We were invited by Dr. Musil to see his famous collection of precious stones. A large table had been placed in the center of his study. The green cloth with which the table was covered was removed by Dr. Musil, and a glittering collection of jewels was revealed beneath the glass top of the table. Although the display was delightful to us, there were so many precious stones that they could not be fully appreciated. It was decided by all of us that we would be more impressed by one beautiful ruby than by a dozen diamonds. (97 words)

Using the Passive Voice Appropriately

Must you eliminate forever all passive sentences from your writing? No, there are uses for the passive voice. It is appropriate in the following circumstances:

• The person or thing performing the action is unknown; for example, Today, Fort Boonesborough has been painstakingly reconstructed. (The writer doesn’t know who did the reconstructing.)

• You want to alter the tone or you want to be indirect; for example, Your resume was received after our deadline, so it could not be considered. (This avoids the harsh statement, You sent your resume in late, so we refuse to consider it.)

• The person or thing that performed the action is unimportant to your purpose in writing; for example, The CEO was honored by the University of Massachusetts, her alma mater, in a special ceremony. (This sentence is good if you are focusing on the CEO, not the university. If you are focusing on the university, use the active voice: The University of Massachusetts honored the CEO, its alumna, in a special ceremony.)

Even with these exceptions, situations calling for the passive voice occur infrequently. Before you use a passive construction, ask yourself if it’s really justified.

USING CONCRETE AND SPECIFIC LANGUAGE

In addition to relying on active verbs as much as possible, you should use nouns that are specific, concrete, and varied. To illustrate the importance of vivid language, let’s look at a bad example from a mythical Chamber of Commerce:

Blandtown has much to offer tourists. We have some nice parks with boating facilities and we have swimming in lakes and pools. In addition, Blandtown has many fine restaurants, and in every season, the area offers several plays, concerts, a dance, and other activities. We have everything you want.

It doesn’t exactly make you want to catch the next plane to Blandtown, does it? Yet the city appears to have many attractions for visitors, so why does it all sound so—well, bland?

For starters, although the verbs are active, they’re flat and repetitive. Five of the six sentences use a form of have, and the verb in the other sentence, offer, is just a variation of it. The other major problem is that the descriptions are general; you won’t find any specific, concrete images that distinguish this city from hundreds of others.

This passage could be made vivid and memorable in two primary ways: by using powerful verbs and by avoiding abstract nouns.

Powerful Verbs

If it fell to you to turn Blandtown into Grandtown—at least in its tourism brochures—you should begin by choosing verbs that describe specific physical actions. The first part of the passage stresses the outdoors with its parks and lakes, so ask yourself what visitors do there. They can picnic, stroll, jog, bike, hike, camp, sail, water ski, wind surf, swim, dive, and splash. At the many restaurants, they can dine, snack, feast, taste, or stuff themselves. And at those cultural activities, they’ll dance, listen, watch, applaud, tap their feet, hum along, or maybe become engrossed.

The next step is to think of concrete details about the places and events, the nouns you’re describing. Let’s say one park, stretching along the shores of Tisane Lake, was designed by the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted; a second park encompasses 150 acres, 20 miles of hiking trails, and 15 miles of bicycle paths. The town has 25 restaurants (including Indian, French, Italian, Jamaican, Greek, and vegetarian), a Japanese teahouse, and two English tea shops. The theaters include the Teapot Dome and an open air arena, and the Blandtown Museum boasts the world’s biggest collection of teapots, donated by Muffy Bland, a descendant of the city’s founder and a sponsor of the annual Tea Ball, which is open to the public. You could go on and on. As your final step, you combine the forceful, varied active verbs with the concrete, specific nouns, and voila!

Something’s brewing in Blandtown this summer, so why not stop in and have a ball? The Tea Ball, that is, where you can dance the night away at the romantic Lapsang-Oolong Mansion. Or if the great outdoors is more your cup of tea, you’ll want to head to Gunpowder Park with its 35 miles of trails, ideal for everyone from the casual stroller to the serious hiker and committed bicyclist. Is sitting and reading a good novel your idea of the perfect vacation? Then you’ll want to steep yourself in the pleasures of Kettle Beach, where you can bask in the sun, slake your thirst with a glass of Bland Brand’s famous iced tea, and cool off with a dip in Creamtea Lake.

Of course, not all topics lend themselves so readily to active verbs (and bad puns), but even when you’re writing about mundane or theoretical topics, you can keep insipid verbs, such as to have and to be, from predominating. Strong verbs not only are more interesting but also convey a sense of action, purpose, and accomplishment. Try to increase the proportion of forceful, specific, concrete verbs in all your writing. Test yourself by changing the dull verbs in Exercise 7–2 to more active ones.

Exercise 7–2: Active Verbs

INSTRUCTIONS:![]() Rewrite the following sentences using more active verbs.

Rewrite the following sentences using more active verbs.

Compare your sentences with those at the end of the chapter.

1. There is a solution to this problem: outsourcing.

2. I was in a supervisory capacity for half the employees in my division at my last job.

3. We had mistrust between us, which was an interference.

4. The only industry that resisted the changes was pharmaceuticals.

5. One of the issues is that we no longer need a separate accounting department.

Vivid Nouns

A word is a symbol that takes on meaning only when you know the thing or concept that it refers to, that is, its referent. For the clearest communication, the referent should be the same for the writer and the reader. The more specific the vocabulary you use, the more likely it is that you and your reader will agree on the referent. You want to call up mental pictures with your writing, and you do that through specific details conveyed by concrete language.

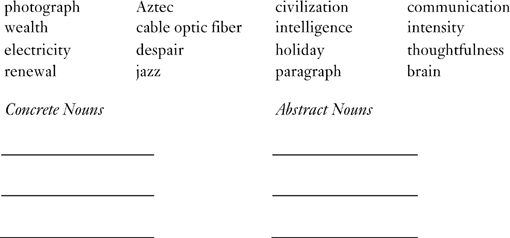

A concrete noun is one whose referent can be perceived by the senses; that is, it can be touched, seen, smelled, heard, or tasted. The following three lists of concrete nouns are arranged from general to specific:

• Event, accident, malfunction, plane crash

• Person, worker, skilled laborer, carpenter

• Sensation, taste, sweetness, maple syrup

We can picture a plane crash more readily than an event. We’re more likely to agree on the referent for carpenter than for worker. Maple syrup is more likely to make our mouths water than a sensation. That’s why you want to find the most specific noun possible when you write.

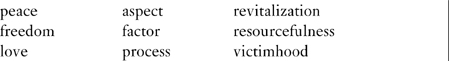

In contrast, an abstract noun has an idea as its referent. The following are examples of abstract words:

When you use many abstract words in your writing, you increase the danger of misunderstanding. Think of all the possible interpretations of words like love or freedom. And does aspect conjure up any striking image in your mind? Probably not, because abstract words tend to be less powerful than concrete ones. Abstract words may elicit strong emotions; nations go to war over words such as honor, freedom, and justice. But if these words call up mental images, they probably are concrete nouns, like flags, ballots, money, property, and books—different images for different people, but all of them vivid and tangible. In Exercise 7–3 you can test your grasp of concrete and abstract nouns.

Exercise 7–3: Concrete and Abstract Nouns

INSTRUCTIONS:![]() Designate the following words as concrete nouns or abstract nouns.

Designate the following words as concrete nouns or abstract nouns.

Who Does What to Whom?

How can you cut down on abstract words in your business writing? One way is to use the who-does-what sentence pattern. Who means the person or thing that performs some action. Does means the verb that defines that action. What means the thing acted upon, if any. Say that you have written this sentence: Conveyance of ideas to an audience requires comprehension of the complexity of the listening process. The sentence is packed with abstract words, which make it unclear who is doing what to whom. Let’s take it apart, fix it, and reassemble it as a stronger sentence.

First, who is doing the action? The person who will comprehend how complex listening is and who will convey ideas. We could represent this person with the pronoun you or the noun speaker. Second, what is this actor doing? Comprehending and conveying. Third, to whom are these actions being done? The ideas are being conveyed to an audience. So, to revise the sentence using the who-does-what model, use you as the subject and make the sentence stronger by substituting more concrete words: To explain ideas to a group of people, you must understand the complex events that occur when people listen.

In the following pair of sentences, a similar process transforms the first, confusing sentence into the second, clearer one:

Going even further into the effects that not having enough petroleum would have on the world is the realization that the thousands of factories in the world that use oil would have to close down. With a global oil shortage, thousands of factories would have to close down.

The second sentence gets rid of the vague nouns effects, world, and realization, not to mention about 20 extra words. That makes it more concise, direct, and understandable.

Verbized Nouns and Nounification of Verbs

Writers sometimes dilute or complicate their writing by transforming active verbs into nouns or vivid nouns into verbs. Here are examples where nouns are used in place of active—and stronger—verbs:

Our recommendation is to give the contract to Hart.

The preference of the committee is that it postpone the announcement until next week.

Successful performance as a master of ceremonies requires memorization of a store of current jokes.

All three sentences are flat and wordy, and the first two are especially dull because they use a form of the verb to be. By employing the who-does-what model and moving the actor to the center of the action, we can take those fat, lazy, abstract nouns and trim them down into taut, active verbs:

We recommend that Hart get the contract.

The committee prefers to postpone the announcement until next week.

To succeed, a master of ceremonies must memorize a store of current jokes.

In English, verbs often come from nouns, but sometimes trendiness takes this linguistic evolution to extremes, as when a researcher asked his colleagues, “How can we disambiguate these data?” The language of business and other public discourse is full of nouns turned to verbs by adding -ize. Along with other fad words, they seem at times to take over our memos, letters, and conversations. In fact, writers seem to feel in danger of being out of it if they fail to toss a catchword or two into everything they write.

Models seem to have vanished, but the world is full of paradigms, which are utilized to facilitate a proactive stance toward sensitizing others towards identity issues. Though some of these faddish words are shorter than the constructions they are meant to replace, they’re jargon, and not particularly enlightening jargon at that. As the language changes, some of these new words may supplant older ones and others will be replaced by new jargon. But until that time, stick to plain English, where examples are used by active people helping others become aware of differences among us.

It’s Absolutely, Totally Unnecessary to Overmodify Very Much

Some writers think that slathering on modifiers— adjectives and adverbs—makes their writing colorful and more interesting. They’re correct to a degree; a well-chosen modifier can make a sentence come alive. But good writing relies primarily on strong nouns and verbs, so one adjective or adverb is usually sufficient, and two are usually overkill. If your verbs are active and accurate and your nouns specific and concrete, you won’t need a lot of modifiers to dress up or qualify what you write.

Think about your response to the following description.

Excited and eager employees crowded good-naturedly, but tightly, into the overflowing auditorium to listen attentively and quietly to the much-heralded and famous movie star speaker on a hot, muggy Friday afternoon.

Were you tempted to run in the other direction? Yet the sentence uses active verbs and concrete nouns and makes it clear who is doing what. The problem is with the modifiers; there are too many of them. If the writer trusted the language to say what she wanted it to, she would have settled for something like this:

Despite the heat on Friday afternoon, employees remained good-natured as they crowded into the auditorium to listen to the movie star.

Too many qualifiers, another kind of modifier, can get in the way of your meaning. Statements replete with hedges or conditional phrases sound wishy-washy and often say less than they seem to say. For example:

We might possibly want to implement the pretty good ideas that came up at the meeting.

Frank has a feeling that Push-Pull, Inc., may be a little too new to the games market to do much of a job for us.

There are times when you don’t want to sound insistent or adamant, but if every sentence stresses your uncertainty, your writing won’t convince anyone. Most qualifiers (e.g., rather, very, little, pretty) can be eliminated. Auxiliary verbs (e.g., would, may, should, could, might) are better saved for real doubt. Following those rules, you can rewrite the previous sentences:

We should consider the good ideas that came up at the meeting.

Frank wonders if Push-Pull, Inc., has enough experience in the games market to do the job well.

Try putting all these suggestions to use in Exercise 7–4.

Exercise 7–4: Edit, Rewrite, Improve

INSTRUCTIONS:![]() The following paragraph needs major editing. Rewrite it as much as necessary, relying on active verbs, vivid nouns, appropriate modifiers and only the necessary words. You’ll find one possible revision at the end of the chapter.

The following paragraph needs major editing. Rewrite it as much as necessary, relying on active verbs, vivid nouns, appropriate modifiers and only the necessary words. You’ll find one possible revision at the end of the chapter.

It will be this week that Alana Rose-Rossley is going to be a lot more successful than she ever dreamed she would be when Yangzee.com, the by far most successful online marketer of old things like collectibles and new things like books, is going to acquire her company, Everything Old Is New Again. There was a rocky and uncertain start, only a mere eight months ago in a leaky garage which wasn’t very protective of the items she was keeping. Today, her new and thriving company is worth $250 million in stock, which makes her a very rich multimillionaire in only eight months. Even in the astronomically mind-blowing fast pace of brand new start-ups on the Internet, Rose-Rossley is pretty unique. This recognizing of her successful accomplishment is something that makes her collecting much, much more than mere memorabilia.

AVOIDING TIRED LANGUAGE

Clichés are the bane of our existence, not worth a plug nickel, but you can’t live with ’em and you can’t live without ’em. So what’s a writer to do? Clichés tempt us because they are more colorful expressions than many of us can think up on our own and, therefore, make us feel more witty than we are. And many tired, old aphorisms are basically true. Probably nothing does succeed like success, in America, anyway; and most of the time, a friend in need is a friend indeed.

Clichés are useful in a superficial way because they abbreviate ideas we seem to share. But they also foster lazy, uncritical thinking by reducing complex ideas or events to sound bites. Phrases such as the glass ceiling and political correctness imply a consensus and a sameness of experience that don’t exist. You may be able get away with using clichés to make a point when you talk, but when you’re writing and have time to come up with more complex thoughts expressed in more carefully chosen words, it’s best to eliminate the clichés.

Even though most of us can spot clichés at 50 paces, they still have a way of slipping into our writing unbidden: A phrase can be so familiar that we include it unthinkingly. The same happens with “word packages”—groups of words that are used together so often we find it hard to think of one word without the others. In business, meetings are productive, discussions are frank, and young people with fire in their bellies enjoy meteoric rises up the corporate ladder only to hit the glass ceiling or meet a tragic downfall because—let’s face facts—they tempted fate by trying to go too far too fast. The rule of thumb (another cliché) is to avoid clichés and word packages in your writing when possible. When it’s not possible, or when clichés make a useful point, keep them to a minimum and move on.

How do you make your writing fresh and energetic? By sticking to rules laid out in this chapter: Write what you mean; use active verbs, vivid nouns, and a minimum of fuzzy or unnecessary words; and choose the specific over the general and the concrete over the abstract. Other guidelines include constructing sentences according to the who-does-what-to-whom model and avoiding trendy words, word packages, and clichés. Your writing, and your thinking, will be clearer and more vigorous if you do all this.

In addition to polishing your own words, you can add force to your writing by taking advantage of other people’s words through direct quotations, which we’ll address in Chapter 8.

ANSWERS TO EXERCISES

Exercise 7-1

Suggested revision:

Dr. Musil invited us to see his famous collection of precious stones, which he had placed on a large table in the center of his study. Sweeping aside a green tablecloth, he revealed a glittering collection of jewels beneath the glass top of the table. We were delighted by the display but could not fully appreciate so many precious stones. We decided that we would be more impressed by one beautiful ruby than by a dozen diamonds. (77 words)

Exercise 7–2

Suggested revisions:

1. I propose we solve the problem by outsourcing.

2. I supervised half the employees in my division at my last job.

3. Our mistrust of each other interfered.

4. Only the pharmaceutical industry resisted the changes.

5. We no longer need a separate accounting department.

Exercise 7–3

Concrete nouns: Aztec, cable optic fiber, electricity, holiday, jazz, paragraph, photograph, brain

Abstract nouns: civilization, communication, despair, intelligence, intensity, wealth, renewal, thoughtfulness

Possible revision:

Dream though she did, Alana Rose-Rossley never imagined she would succeed so quickly. Yangzee.com, the Internet’s largest marketer of everything from collectibles to books, announced this week that it is acquiring her company, Everything Old Is New Again. Begun only eight months ago in a leaky garage, the company is now worth $250 million in stock. Even in the fast-paced world of Internet start-ups, Chernowitz is unusual: a sudden millionaire collecting much more than memorabilia.

1. The following sentence illustrates what writing principle? Approval of all vouchers must be done before payment is made by the treasurer. |

1.(d) |

(a) the who-does-what model |

|

(b) the active voice |

|

(c) overmodification |

|

(d) the passive voice |

|

2. Concrete nouns: |

2. (d) |

(a) describe states of being and emotions. |

|

(b) are weaker than abstract nouns. |

|

(c) include such words as colors, hopelessness, and ambition. |

|

(d) are words whose referent can be touched, seen, or heard. |

|

3. Which revision of the following sentence is most specific? A period of unfavorable weather conditions involving precipitation came throughout the day. |

3. (b) |

(a) There was a period of bad weather conditions today. |

|

(b) It rained all day. |

|

(c) Unfavorable weather prevailed in the area during the day. |

|

(d) The weather today could have been better. |

|

4. The passive voice is appropriate when: |

4. (a) |

(a) the person performing the action is unimportant to your message. |

|

(b) you feel uncertain. |

|

(c) you feel guilty. |

|

(d) you’ve already used the active voice once in the sentence. |

|

5. Which is an abstract noun? |

5. (b) |

(a) mother |

|

(b) motherhood |

|

(c) daycare |

|

(d) maternity leave |

Review Questions

Review Questions