6

Language That Works

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Name four elements that promote a positive verbal climate.

• Explain the uses of warm and cold language.

• Cite one way to test the precision of your writing.

• List three ways to make your writing more concise.

• Explain what a mixed metaphor is and how to avoid it.

In this course, we’ve noted several skills essential for successful writers. They know how to encourage their audience to read their message, they explain their thoughts clearly and directly, and they use the right word—not just one that comes close. In short, they create a good verbal climate.

A good verbal climate is generally a positive one. It starts with the assumption that the writer and readers are people of good faith and reasonable intelligence who are interested in sharing ideas and information. Four elements promote a positive verbal climate:

• Knowing your audience

• Being sensitive to language that might offend readers

• Using an appropriate tone

• Creating strong verbal images

We’ve addressed the first two elements in earlier chapters. Now we’ll look at the third and fourth components of a good verbal climate. Finding the right tone can take time and require rewriting. In a way, each time you sit down to write, you face the challenge anew. But finding an appropriate tone is essential to writing well, so it is worth the effort.

FINDING THE RIGHT TONE

Because language and thought are intertwined, you communicate your attitude toward your subject and your readers through the tone of your writing. Your tone is determined by the words you choose. If you’re enthusiastic about a proposal, that’s likely to come through in your writing and kindle a similar feeling in your reader.

Negative emotions, such as impatience, annoyance, or disdain, can slip into your writing too and be absorbed by your readers. Harsh words spoken in the heat of a disagreement may be forgotten over time, but angry language put in writing is there to stay. So it is crucial that you show respect and avoid condescension toward your readers. Even if you have good reason for thinking someone is a fool or worse, it’s to your benefit to keep your style of address and the tone of your language polite and professional.

Your tone is also revealed in your level of writing. Good writing is appropriate writing—appropriate to your readers and the situation. So the right tone requires attention to your readers’ level of understanding; it should be neither pretentious nor patronizing. Some people think that by using the fanciest words in the dictionary they demonstrate how smart and classy they are. They parade their vocabulary, whether it is appropriate or not, and they sprinkle their writing with more foreign phrases than Berlitz.

But words and expressions that are pompous, outdated, overused, or overblown interfere with getting a message across. When choosing vocabulary, pick words your readers will understand; forego foreign phrases, unless they’re part of conversational English or you can find no adequate substitute; and avoid clichés like the plague.

CHOOSING THE RIGHT VERBAL IMAGE

Successful business writers try to find words that do more than state basic information. They aim to create favorable images in the minds of their readers. They are aware that words with threatening or distasteful connotations cause people to tune out, argue, become defensive, or resist what they read, even though they might agree with the message.

Attention to language can get out of hand when words become scapegoats for all of society’s ills. Words aren’t dangerous in themselves, but they can be powerful nonetheless. They can hurt feelings, spread lies, get people riled up, pass on prejudices, exacerbate hostility, and do other things that are undesirable in business dealings. That’s why it’s important to be careful in using words that have ambiguous meanings or highly charged associations. Such language makes a strong statement, but it is effective only if that’s the statement you want to make.

Loaded Words

As soon as we learn to talk, we’re taught that certain words are good and others bad, or “not nice.” As we grow up, we continue to hone our awareness of which words will get us what we want and which will make people angry or resistant. We understand, often without being aware of it, that some language is “loaded”; that is, it is emotionally charged or it suggests bias.

Advertising copywriters, salespeople, politicians, journalists, lobbyists, and poets are particularly adept at manipulating loaded language, but nearly everyone uses it, intentionally or otherwise. In fact, the world would be a pretty dull place if we bled all emotion or opinion from our speech and writing. When we’re describing how someone we like acted in a meeting, we might say, “Carter made a powerful bid for support and convinced the other side that he was right.” But if we disagree with Carter or his tactics, we’re likely to describe the situation differently, saying something like, “Carter brow-beat the other side and forced them to go along with him.”

Which is right? The answer depends on your motives, so a more useful question might be, Which serves your writing better? You could describe an accountant as stingy—it’s vivid and perhaps accurate—but if you don’t want to alienate most accountants, thrifty or frugal is probably a better choice. Similarly, tact encourages us to note that negotiators are persistent, rather than pigheaded, and lawyers are concerned about legalities, not paranoid.

Language can be loaded in a positive way, too. For most people, the words winning, effective, and profitable have favorable associations, which can be used to sweeten what otherwise might be a dubious proposition.

Used in fair persuasion, loaded words can be effective and appropriate. But loaded sentences stated as incontrovertible facts provide weak evidence and persuade, if at all, by bullying or silencing differences of opinion. Used in these ways, loaded language is manipulative and dishonest.

Since the connotations of words change over time, it would be impossible to list all the loaded words to watch out for, so our intention here is just to make you aware of the weight and effect of the language you use in your writing, because your readers certainly will be aware of it.

Positive and Negative Associations

The positive or negative associations words accrue may limit their use. It is obvious that smearing someone with a negative label is not the way to win a supporter, but it may be less apparent (or forgotten under pressure) that positively worded messages win more allies than their negative versions. This can work quite simply, as you can see by comparing the sentences in each of the following pairs:

You’d better not miss the deadline. (negative)

I know you’ll make the deadline. (positive)

We won’t have an idea about raises until next year. (negative)

We’ll find out about raises by the first of the year. (positive)

The second statement in each pair not only substitutes positive for negative language; it also reflects positive thinking, another example of how language and thought interact.

Positive writing also depends on how messages are organized. As we pointed out in Chapter 1, even if you’re writing an essentially negative message (e.g., correcting a mistake or asking that a report be redone), it helps to begin with a positive or at least neutral statement, if possible. Usually, even bad reports have some redeeming qualities, and by noting those first, you start with a verbal climate in which your reader is more likely to heed your criticism and suggestions. Keep in mind, too, that there are different ways to criticize.

Warm and Cold Words

Words vary not only on a negative-positive scale but also in their warm and cold associations. Warm words are pleasant or reassuring, whereas cold words are harsh or impersonal. Skilled use of warm and cold language allows you to create strong images and to modify your tone according to your aims. It can give you the means to make a point without making it too pointedly.

Cold language can be useful when you want to be firm, reserved, or blunt, or if you want to separate yourself from your reader or keep him or her at a distance. You may also have to use cold language with a negative message that can be phrased positively only through euphemism, a technique that not only lacks candor but can result in confusion and more ill will. At other times, you may intend to shake up someone who has failed to do something, or you may want to end a working relationship. In such cases, you could use cold language to write, Your company’s failure to deliver your product on schedule has made us miss our deadline. We cannot accept this and will terminate our contract at the end of the month.

In a situation where your aim is to improve a working relationship, it is probably better to avoid cold words like abuse, failure, negligence, or delay at the beginning of a written message. Such words put readers off, particularly when you preface them with a form of the personal pronoun you, as in your failure or you’ve delayed in sending. . . . Cold language carries extra weight when it is aimed directly at an individual, so take care when you use it in such a situation.

When your intention is to provoke an action or enlist readers in your cause, you benefit by using pleasant words, such as admirable, improvement, deserving, or satisfaction. Pairing these warm words with you (You’ve done an admirable job) magnifies their positive effect.

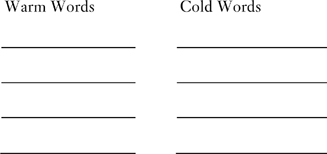

Exercise 6–1 tests your grasp of warm and cold words.

Exercise 6-1: Warm and Cold Words

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() put the following words under their appropriate heading, either warm word or cold words.

put the following words under their appropriate heading, either warm word or cold words.

BEING PRECISE

Obviously, it is important that your writing say what you mean. This requires that it be logical, that you use words correctly, and that you put them in the right order.

Writing Logically

To test your writing for precision, ask yourself if it makes sense. Imprecise writing usually doesn’t make sense or is too confusing for the reader to be certain what you are trying to say. To see how this works, read the following sentence out loud: The cost of cable access is becoming increasingly expensive. Does something sound wrong? It ought to, because it’s not the cost that is becoming expensive; it’s cable access itself. A revision, based on logic, would be, Cable access is becoming increasingly expensive.

You can pick up mistakes with your ears that you miss with your eyes, so reading your writing aloud often alerts you to words or sentences that need changing. It also helps you pick up wordiness and excessive detail. It can help you at an earlier stage, too, if you’re having trouble phrasing an idea clearly. When that happens, lean back from your desk and say what you mean aloud, as if you were explaining it to someone. At this stage, don’t worry about getting the clauses or commas right. Once you’ve come up with a statement that satisfies you, you’ll probably find that you can write it clearly and grammatically.

Using Words Correctly

Precision also demands that you use the right word, not one that sounds like it will do. It’s easy to mix up words that sound similar and are close in meaning, as this sentence demonstrates: Many managers are adverse to criticism from their employees. The word adverse, which refers to something that opposes or hinders progress, has been confused with averse, which means opposed or feeling strong dislike. Averse is the correct word for this sentence.

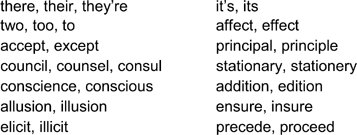

Also be careful with confusing words that sound exactly alike (or so nearly alike as to be easily confused) but are spelled differently and mean different things. These are known as homonyms, and English is full of them. Exhibit 6–1 lists homonyms commonly confused in writing.

Many other words come in confusing pairs or triplets and often are carelessly exchanged even though they have very different meanings. Exhibit 6–2 explains the correct usage of a dozen sets of frequently misused words.

Finding the Right Word

Imprecision also occurs when words are not matched properly with other words. In the sentence, Dissatisfaction grew like weeds, but management preferred to sweep it under the rug, we’re tripped up because the writer has combined two images that don’t go together: untamed plant growth and sloppy housekeeping. This creates what is known as a mixed metaphor. The sentence would be better if it used fresher language and stuck to a single image.

When you pay attention to the logic of your words, you save your reader from having to question it. Consider this sentence: Dr. Rashid Johnson said that the field of agronomy is no more satisfied with mediocrity than doctors or pilots. The sentence compares agronomy (a field of study) with doctors and pilots (people). We can guess that the writer wanted to compare agronomists (not the field of agronomy) to doctors and pilots but, to say that, he or she should have written, Dr. Rashid Johnson said that agronomists are no more satisfied with mediocrity than are doctors or pilots.

Notice two things: First, the change to agronomists makes the comparison among three groups of people clear. Second, the repetition of the verb are makes it clear that doctors and pilots are being compared with agronomists, not with mediocrity.

Frequently Misused Words

All right (adjective phrase) Everything is okay; all correct

Alright A questionable alternative spelling of all right, which is the preferred form

• We felt all right about the solution.

Among (preposition) Used with more than two people or things

Between (preposition) Used with only two people or things

• The bonus will be divided among the executives.

• You will have to choose between Craig and Tory for the award.

Amount (noun) Refers to things that can be weighed or assessed in bulk or mass and to a specific cost

Number (noun) Refers to things that can be counted

• We need a large amount of gravel for the construction project.

• A number of checks are missing. The total is a large amount.

Bring (verb) To carry toward the person who is speaking

Take (verb) To carry away from the person who is speaking

• Please bring the reports to me at my desk.

• Please take the contracts home with you.

Can (verb) Used to denote ability

May (verb) Used to denote permission

Both can and may denote possibility.

• The broker may attend the seminar. (Or he may not.)

• The broker can attend the seminar. (He is physically able to.)

• Brokers, as well as other businesspeople, may attend the seminar. (They are permitted to attend.)

Compared to Used to represent one thing as being similar to another without going into specific characteristics; to liken

Compared with Used to note specific similarities and dissimilarities, as in a side-by-side

evaluation

Contrast with Used to show the difference between two things

• The development of the personal computer is sometimes compared to the invention of the printing press.

• Compared with today’s computers, those built only five years ago are incredibly slow.

• The magazine contrasted the ease of using the new software with that of the old version.

Disinterested (adjective) Impartial or unselfish

Uninterested (adjective) Not interested

• The boss chose a disinterested employee to settle the argument.

• As an uninterested student, she often yawned.

Fewer (comparative) Used with items that can be counted

Less (adjective) Used with quantity, degree, or bulk

• There was less objection than we anticipated to the proposal that we hire fewer people.

Imply (verb) To suggest or hint at

Infer (verb) To deduce or conclude

• The supervisor implied in her pep talk that she is worried about production.

• The workers inferred from the talk that the supervisor is worried about output.

Literally (adverb) In a literal or strict sense; really; actually

Figuratively (adverb) Metaphorically; as a figure of speech

Virtually (adverb) For all practical purposes; almost

• Only dragons and fire-eaters literally breathe fire.

• Jeremiah used the word coup figuratively, but many of his readers took it literally.

• Virtually no employee got a good recommendation.

Presently (adverb) Soon; in a little while

Now (adverb) At this time

• Roberto called to say he will be arriving presently.

• Now we’re waiting for him.

Than (conjunction) A subordinate conjunction used to introduce a comparative clause

Then (adverb) Soon afterward; at that time; at another time; therefore

• Then she spoke about her fears.

• We would rather adjust our plans now than pay the price later.

In Exercise 6–2, you can practice writing precisely.

Exercise 6–2: Precise Writing

INSTRUCTIONS: ![]() Rewrite the following sentences for precision and accuracy. Your revisions may require more than one change per sentence. Compare your sentences with those at the end of the chapter.

Rewrite the following sentences for precision and accuracy. Your revisions may require more than one change per sentence. Compare your sentences with those at the end of the chapter.

1. Diversity concerns played a factor in the decision.

2. Computers to compile statistics are faster than doing it by hand.

3. Compared to my enthusiasm, Sara’s disinterest in the subject was literally mind-boggling.

4. We will be effected by technological advances that are changing like wildfire.

5. The market broke into applause when the Dow closed at a record high.

BEING CONCISE

Precise and appropriate words alone aren’t enough. When you write for business, you must also be concise. Think of your own reactions when a piece of writing hits your desk. Chances are, you don’t have the leisure to slog through redundancies or ponder a fanciful turn of phrase. You appreciate writers who get to the point quickly with a minimum of fuss. You want enough information to tell you what you need to know, but you want it in as few words as possible. That valuable quality is conciseness.

Conciseness is not the same as brevity. A brief report may use more words than necessary and still not give adequate information, whereas a long report may be written concisely, though it contains complex ideas that cannot be expressed in few words. How do you make your writing concise? Three easy techniques will help.

Eliminate Fillers

First, get rid of empty words that add no meaning to your message. For example, in the sentence, It is also interesting to note that luxury auto sales increased last month, the first seven words are padding. If it’s not interesting, why write it? You get a stronger, tighter sentence if you eliminate them: Luxury auto sales increased last month. If each word cost you a dollar, the reduction from 13 to 6 words would yield a 54 percent savings.

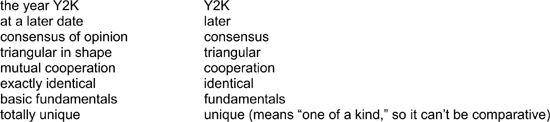

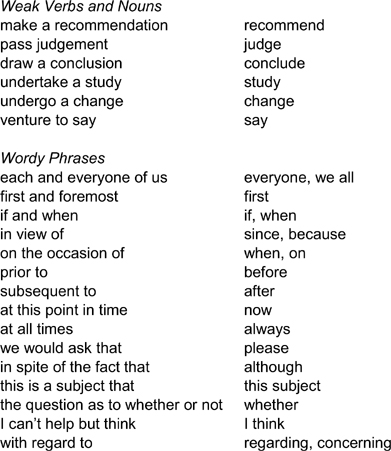

Be alert for phrases that say nothing in many words. Exhibit 6–3 lists several common ones.

These phrases are usually just verbal spinning of your wheels, as if you’re revving up to get to the point. Usually, you can eliminate them with no loss in meaning and some gain in clarity, as in the second sentence of each of the following pairs:

There are two supervisors who will attend the conference.

Two supervisors will attend the conference.

Fillers

there is

due to the fact that (due to is not a correct substitute for because)

in order to

the reason why

with respect to

with the result that

I seem to think that

actually, really, literally

my personal opinion is (how can you have an impersonal opinion?)

Due to the fact that we have to pick up Tom, we’ll be late.

We’ll be late because we have to pick up Tom.

My personal opinion is that the trade show will be a bore.

I think the trade show will be a bore.

Eliminate Repetition

Second, don’t repeat what you’ve already written. Wordy writing often repeats ideas unnecessarily. For example, true facts uses two words to say facts, which, by definition, are true. You will find other redundant phrases and their short forms listed in Exhibit 6–4.

Sometimes two phrases in a sentence repeat the same idea:

Just after the contract began, union members decided that the terms of the contract were not satisfactory because the economic situation had changed, but this decision wasn’t reached until after the contract went into effect.

The sentence takes 35 words to end with the same idea with which it began—and probably not because the writer was afraid the reader would miss that information. Such repetition occurs more often in longer sentences because the writer forgets the beginning by the time he or she finishes. Careful editing and reasonably short sentences will help avoid this. If, on rewriting, the writer omitted the second main clause, the sentence would be shortened (20 words) as well as improved.

Just after the contract began, union members decided that its terms were not satisfactory because the economic situation had changed.

Repetition also occurs when a sentence repeats an idea from a previous sentence, or a whole paragraph repeats an idea in a previous paragraph. This kind of wordiness usually comes from the writer’s fear that the first statement was not clear or forceful enough. You should be alerted to the possibility of this redundancy by phrases such as in other words, this means that, or that is to say. Avoid repetition by choosing one statement, reworking it until it is clear, and then eliminating the repetitive one. Writing from an outline also helps.

Condense Phrases and Clauses

Third, limit phrases and clauses to their essentials. Wordiness often occurs when you use a phrase that can be condensed to a single word or a clause that can be condensed to a phrase. The chief cause of wordy writing is wordy speaking. Spoken English is inherently redundant because speech is subjected to interruptions, ritualizations, and demands for a purely comforting drone of sounds that carry little or no specific meaning. Writing evolved from speaking, but the two serve distinct purposes. We miss some of what is said to us because listening is inefficient, but in writing, we can edit, and our readers can go back and reread if they don’t catch something the first time around. So we don’t need to state our ideas as elaborately and redundantly as when we speak.

Phrases that pair a weak verb with a noun usually can be shortened and made stronger when they are rewritten as verbs. Other phrases that don’t contain similar clues can be condensed, too. In Exhibit 6–5, you’ll find examples of common wordy phrases and ways to condense them:

Modifying clauses beginning with who, which, or that can often be condensed to an adjective or phrase:

The building that is made of brick will be renovated by next year. (13 words)

The brick building will be renovated by next year. (9 words)

Mr. Arkashdian, who has been a supervisor for 10 years, will retire soon. (13 words)

Mr. Arkashdian, a supervisor for 10 years, will retire soon. (10 words)

Can writing be too concise? Yes. In most business writing, you don’t want your message to sound like an order from a drill sergeant. Truncated writing that omits articles and connectives sounds unnatural, and your message may be interpreted as insultingly curt. Try to strike a balance between concise, efficient writing and a friendly, human tone.

Exercise 6–3 gives you an opportunity to practice tightening up wordy sentences.

Exercise 6–3: Tight Writing

INSTRUCTIONS:![]() Rewrite the following sentences to make them more concise. Compare your versions to those at the end of the chapter.

Rewrite the following sentences to make them more concise. Compare your versions to those at the end of the chapter.

1. The reason is because it’s required by local regulations.

2. We have a problem; in other words, something is wrong.

3. It was due to the fact that I had a crisis situation on my hands that I found myself unable to give my personal opinion, as I would in the normal course of events.

4. Each and every one of the group of agents called us on the occasion of Rosalind’s promotion.

5. I have to say it was hard to draw a conclusion about the question of whether of not we should sell assets, which was the issue at hand.

The art of good writing is to say exactly what you mean clearly, precisely, and concisely. When other concerns interfere—trying to impress readers with your vocabulary or using worn or sloppy phrases—the quality of the writing and, hence, the value of the communication suffer. In business writing, the writer should not get in the way of the written message. Keeping this simple rule in mind may help you find the clearest, most precise, most concise, and most elegant way to write what you need to say.

You need to be aware that some words are loaded, have positive or negative associations, and are perceived as warm or cold. With this knowledge, you can use these variations for your purposes. You also need to be attuned to making your writing precise and logical; one test is to read your writing aloud so that your ear can catch mistakes or ambiguities that your eye misses.

Effective writing requires you to use the correct word, not just one that’s close. Finally, you need to strive to write concisely, which includes eliminating fillers and repetition and condensing overly wordy phrases and clauses.

In the next chapter, we’ll look at how to make that message strong as well as effective.

ANSWERS TO EXERCISES

Exercise 6–1

Answers:

Warm words: advantage, agree, benefit, capable, fulfill, generous, honest, improvement, privilege, profit, progress, reliable, sincere, success, trust

Cold words: allege, bias, blame, careless, defective, dissatisfy, fail, fault, inadequacy, inappropriate, inferior, mistake, neglect, sloppy

Exercise 6–2

Suggested revisions:

1. Diversity concerns played a role (or were a factor) in the decision.

2. Using computers to compile statistics is faster than doing it by hand.

3. Compared with my enthusiasm, Sara’s lack of interest in the subject was mind-boggling.

4. We will be affected by technological advances that are spreading like wildfire.

5. Traders on the floor (or some other group of people) broke into applause when the Dow closed at a record high.

Exercise 6–3

Suggested revisions:

1. Local regulations required it.

2. We have a problem. Or, Something is wrong. (not both)

3. Because of a crisis, I was unable to give my opinion, as I normally would.

4. Every agent called us when Rosalind was promoted.

5. It was hard to decide whether to sell assets.

1. Good business writing is always: |

1. (d) |

|

(a) elegant. |

|

|

(b) terse. |

|

|

(c) lean. |

|

|

(d) appropriate. |

|

|

2. Choose the best revision of the following sentence: Do not lower the quality of the product. |

2. (a) |

|

(a) Keep the quality of the product high. |

|

|

(b) I urge that you don’t lower the quality of the product. |

|

|

(c) There are reasons to keep the quality of the product high. |

|

|

(d) Please do not lower the quality of the product. |

|

|

3. Presently means: |

3. (c) |

|

(a) now. |

|

|

(b) in attendance. |

|

|

(c) soon. |

|

|

(d) afterwards. |

|

|

4. Warm words: |

4. (d) |

|

(a) include accomplish, merit, and delay. |

|

|

(b) are always best for written communication. |

|

|

(c) make writing sound simplistic. |

|

|

(d) are particularly effective when used with a form of the personal pronoun you. |

||

5. Infer means: |

5. (b) |

|

(a) to suggest. |

|

|

(b) to deduce. |

|

|

(c) to imagine. |

|

|

(d) to imply. |

|

xhibit 6–1

xhibit 6–1

Review Questions

Review Questions