Traditionally islanders drew their drinking water from the mountain streams and carried it to their huts in whatever vessel they could fashion.

As a result, most people didn't live or work very far from the water supply. Poor access to water also made farming very difficult. These realities limited the island's overall productivity.

One year, a terrible drought descended and dried up many of the mountain streams. The hardship just about wiped everybody out.

The islanders searched for a solution that could prevent such a calamity in the future.

The fertile mind of Able Fisher V (Able's great-great-great-grandson) tackled the problem. He noticed that rain runoff collected in ponds. Taking his cue from nature, he devised a runoff and reservoir system where rainwater could be collected and stored for future use. But this would be a big project, furnishing the entire island with water.

As Able V conceived it, the Water Works project would require working capital of 182,500 fish...enough to support a crew of 250 men for two years while they labored. He went to Manny Fund for a loan. Manny loved the idea but he just didn't have enough fish. Fearing the worst, Able then tried the bank.

To his surprise, Maxine Goodbank (another descendant) had a receptive ear! Although the price was indeed high, when weighed against the potential rewards, the risk seemed justified. If it worked, the project would pay for itself and ensure a better future for every islander!

But no matter how much she liked the idea, Goodbank would not have been able to finance the project if the island had not saved enough to pay for it. There simply would not have been spare fish to feed 250 non-fishing workers for two years.

But upon completeion, the Water Works delivered as advertised and allowed the borrowers to pay back their loan plus interest.

Islanders were happy to pay yearly fish fees for the running water. From these payments, Water Works employed more than 100 workers year-round to tend the system's intricate bamboo pipe system.

The splashing success of the Water Works project flowed through the island's economy. Pipelines, available for a reasonable charge, brought water great distances, and allowed previously infertile land to produce crops.

The steady flow of water could be harnessed to operate machines, giving birth to new industries.

Relieved of the task of hauling water by hand, everybody now had more time available for the production of consumer goods and services and for the development of new capital projects. The increased productivity allowed society to catch even more fish, and living standards rose as a result.

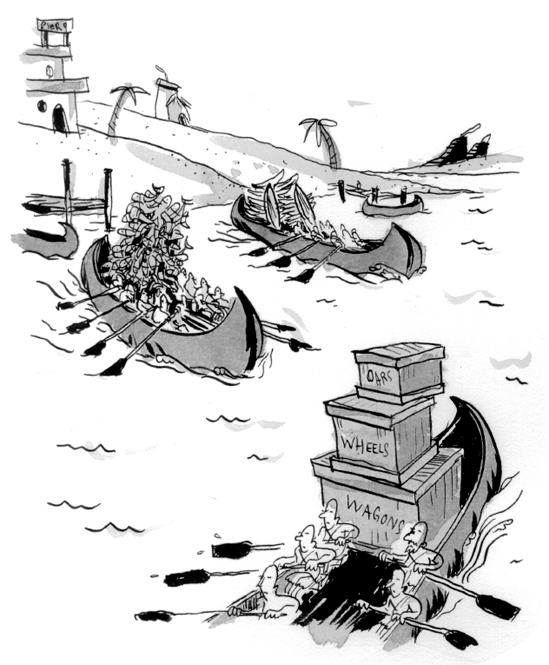

As the island economy expanded, its ability to export production abroad increased as well. Soon giant cargo canoes were sailing over the open ocean, fully loaded with fish, carts, surfboards, spears, and canoes. In exchange for these products, which had gained an ocean wide reputation for quality and affordability, the cargo canoes returned with fresh fish and other trade goods previously unknown on the island.

As the island's explorers came into contact with other islands, trade developed that further stimulated growth. When allowed to flourish unhindered, free trade benefits everyone.

Some islands (or cities, countries, or even people for that matter) often have a relative abundance of something that others don't. Each person, country, or island will naturally use its own particular advantages to get the most reward for what it has.

For instance, the nearby island of Bongobia had a great quantity of—you guessed it—bongos. The natives had perfected the craft of bongo-making and their island was overgrown with the best trees for making bongos. As a result, there were so many bongos on the island that each individual drum was not worth much. As a domestic trade good, a pair of bongos didn't go too far.

One hundred miles from Bongobia, the island of Dervishia was populated by natives who were smitten with bongos. Unfortunately, their environment lacked the right kind of trees to make them. As a result, on Dervishia bongos were a scarce and valuable trade good. What the Devirshes did have was an abundance of coconut tanning oil. But the dark- skinned Dervishes had no need for UV protection, so tanning oil was nearly worthless to them.

But as fate would have it, the fair-skinned Bongobians suffered from chronic sunburn due to the island's unrelentingly sunny weather.

When the two islands finally made contact with one another, they instantly developed a robust trade in bongos and tanning oil. Each island used its competitive advantage to send the other island products that were more valuable overseas than they were at home. In this symbiotic arrangement, both islands benefited. Living standards rose...and well-toned drumming was achieved by all.

Trade on a national level is no different than labor specialization on a personal level. Each individual, or country, trades what it has in abundance, or what it does best, for the things that it doesn't have or can't easily make.

Infrastructure spending can make a huge impact on an economy. But such spending is helpful only if the benefits exceed the costs. If not, the projects waste resources and hinder growth.

Currently, many politicians and economists erroneously view infrastructure spending not as a near-term cost that may lead to long-term gain, but as an immediate means to create jobs and boost the economy. This view can lead to costly misallocations of resources and the unseen destruction of jobs in other areas.

Over the past half century the United States has vastly underinvested in infrastructure. The cost of undoing this neglect is a burden on the current economy. The payoff comes in the future, and only if the work is successful.

In our story, the 182,500 fish borrowed to build the Water Works were no longer available to fund other job-creating investments. That's a big chance to take. Had those fish instead been spent on a worthless infrastructure project, such as Alaska's famed "Bridge to Nowhere," the island's savings would have been squandered and 250 islanders would have wasted two years' labor.

For much of the early history of the United States, projects like the Water Works were often private sector initiatives. But given the inherent unpredictability about the success of these projects, in our age of nearly universal government control it seems inconceivable that such an undertaking could be funded, built, and operated equitably by profit-driven private companies. But in those days they were.

For example, the New York City subways were largely built by private companies and were operated outside of city control for almost four decades. Despite the staggering construction costs, the railroads were able to operate at a profit. What's more, the fare never went up in 40 years.

These days, it's very easy to convince voters that large public amenities—like sewers, highways, canals, and bridges that are meant to benefit everyone—need to be run by the government. Politicians have successfully argued that private companies, which are motivated solely by profit, would exploit the public at the earliest opportunity.

The evidence supporting these claims is largely emotional. What is far more certain is that the government's monopoly control of public projects and services almost always leads to inefficiency, corruption, graft, and decay.

When a government project experiences cost overruns or poor service, free market discipline does not come to the rescue. The government simply raises taxes to fill the gap. In so doing, it wastes societal resources, and living standards drop.

Trade suffers from similar misconceptions. In their quest to protect American jobs from overseas competition, the opponents of free trade ignore the benefits of imports and the hidden costs to consumers that result from restricted choice.

For instance, if a foreign manufacturer can deliver T-shirts to the United States that sell for less than domestically produced alternatives, then Americans can spend less on T-shirts.

The money saved would be available to be spent on other things.... skateboards perhaps. This would benefit the skateboard companies that may still be located in the United States and that can deliver the most valuable product in their category.

But what about the workers of the domestic T-shirt manufacturers who lose their jobs? If their employers cannot find ways to compete more effectively in the T-shirt business, it is true that the workers will have to find other work. But it is not the aim of an economy to simply provide jobs, but to create jobs that maximize labor productivity.

Society as a whole is not helped by perpetuating inefficient use of labor and capital. If the United States no longer has a competitive advantage in T-shirts, it must find something else in which it does.

If trade barriers were erected to protect those jobs, the cost of T-shirts would stay high. People would have less money to spend on skateboards (for instance), and those manufacturers would suffer. And so while it's easy to put your finger on the job that is saved, it's far more difficult to see the job that is lost.

It makes no sense to waste our labor making things that can be produced more efficiently abroad. If we focus on the things that we can make more efficiently than anyone else, then we can trade those products for the things that others produce better. In the end we'll have more stuff.

Of course, the problem is that because of our artificially high currency, high taxes, and restrictive wage and labor laws, we just are not competitive in enough product categories. That has to change.