With the influx of Sinopian savings pushing down interest rates, Usonian entrepreneurs descended on bank loan officers with their best business ideas. But as the jobs of fishing and producing became increasingly outsourced to the Sinopians, the business plans they presented were very different from those the bank had seen in prior generations. Most business proposals now favored companies that required local workers to deliver a service. These jobs could not be outsourced and were generally less capital intensive.

In a celebrated oration given at the island's first economic conference, Brent Barnacle explained the changes. He argued that the Usonian economy had developed to the point where the lowly process of fishing and production could be relegated to poorer economies, leaving Usonians free to pursue more sophisticated "service sector" jobs like chefs, storytellers, tattoo artists, and the like.

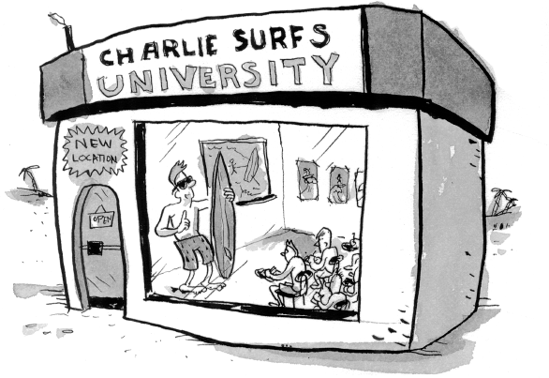

Evidence of this change could be seen at Charlie Surfs, the venerable surfboard shop established by one of the island's founders.

After generations of manufacturing success, the company was moving in a new direction. Charlie's descendants landed a big loan to vastly expand their surfing school operations. Twelve new gleaming campuses were built across the island.

At the same time, the company struck a deal to manufacture its boards in Sinopia, paying off the foreign workers with Fish Reserve Notes, The higher-value activities of surfboard design and surfing instruction remained at home.

Soon more service sector businesses began to take root. The manufacturing facilities that had once populated the island began to be replaced by retail operations that sold goods primarily made on other islands.

The outsourcing trend was accelerated by various regulations, fees and taxes imposed by the Senate to make businesses cater to voters concerns. These obstacles made it harder for Usonian businesses to compete in the new trans-ocean economy.

Meanwhile, across the ocean, Sinopia was being transformed as well....

As expected, the imported net technology, combined with the energizing power of self-interest, caused fishing productivity to soar. Eventually Sinopians saved enough to build numerous mega-fish catchers of their own (the copyright infringement lawsuit brought by the original designers went nowhere in the Sinopian courts). They implemented a 24-hour fishing policy, with three shifts cranking out fish nonstop. A good portion of these fish were exported to Usonia.

As fish production became more efficient, workers were freed up for other tasks, most notably, manufacturing.

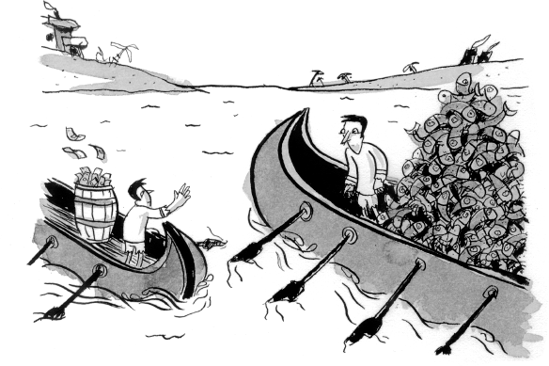

As canoe load after canoe load of fish and goods headed across the sea to Usonia, a flood of Fish Reserve Notes headed in the opposite direction.

In a typical trade relationship (like the one between Bongobia and Dervishia), Sinopian goods would have been exchanged for Usonian goods that were in demand back in Sinopia. But the Sinopian willingness to accumulate notes produced a completely different relationship in which one island largely produced and the other consumed.

Why the Sinopian king would tolerate such an arrangement puzzled many. But in comparison to some of his earlier schemes, this one seemed downright logical. The policy kept the king firmly in control, but it was hardly a boon to the Sinopians who made surfboards but were too busy working to ever surf themselves.

Of course, the Sinopians believed that their ultimate reward would come in the future, when they could stop fishing and live off their savings of Fish Reserve Notes. Little did they realize that Usonia lacked the fishing capacity to feed its own citizens, let alone make good on all its outstanding notes

At another island economic conference, Brent Barnacle claimed that this system represented the newest and most efficient example of economic specialization.

He explained that Usonia had a comparative advantage in consuming, and that this capacity was a great benefit to the entire ocean. No other island, he argued, had citizens of such voracious appetites, who could always be relied on to demand more. Usonians' wide roads, big carts, and big huts made them the most efficient consumers!

The optimistic, can-do spirit of Usonia also meant that its citizens never feared to spend...even when they didn't have two guppies to rub together. As a result, other islands could efficiently outsource consumption to Usonia!

On the flip side, Barnacle explained that the Sinopians were considered the best at generating savings and manufacturing products. Therefore, he argued, "It is simply more efficient to outsource production to Sinopia."

Over the past decade, the problem of global imbalances has been a perennial topic at all the most important economic events. But despite the speeches and the acres of newsprint devoted to the topic, there has been absolutely no progress made toward resolving the problem.

The most visible statistic that charts the phenomenon is the U.S. trade deficit. For most of our history the United States exported much more than it imported, resulting in trade surpluses. In some years, especially toward the middle of the twentieth century, these surpluses were truly massive. We used the excess funds to build more capital at home, and to buy up more capital abroad. In the process we became the richest country on the planet. But in the late 1960s the trade balance started to change, and by 1976 the United States began running persistent trade deficits.

The dollar's reserve status has played a significant role in allowing this deficit to grow unchecked. Without the built-in demand for dollars made possible by the global economic system, no country could long sustain such imbalances. Companies and governments would simply refuse to trade goods for a currency with which it couldn't buy anything.

During the 1970s and 1980s these deficits were on the magnitude of $10 billion to $50 billion per year—large, but manageable. In the 1990s, the figures started hitting the $100 billion mark. Although the extras digits were alarming, the gap was still relatively small in comparison to our massive economy. But with the new millennium, things started to get silly.

For the first decade of the twenty-first century, which corresponded with the rise of China as an export economy, the U.S. trade deficit averaged around $600 billion per year, topping out at a staggering $763 billion in 2006. That's more than $2,500 for every man, woman, and child in the United States.

After the recession of 2008 began, those figures mercifully started to retreat. But as we will see, U.S. policies soon put an end to that positive reversal.

Normally, trade deficits tend to be self-correcting.

A country with a trade surplus, in that it sells more abroad than it buys, will create an international demand for its currency. If you want its stuff, you need its currency. As a result, strong trading positions tend to strengthen a country's currency. The opposite is true with countries with weak trading positions. If no one wants your stuff, no one really needs your currency.

But when a country's currency rises, its products become more expensive. This gives a competitive opportunity to countries with weak currencies to start selling some of their products into that market. When they sell more, demand for their currencies rises. This currency counterweight should keep runaway trade imbalances in check.

But the dollar's reserve status, and the decision of the Chinese government to maintain the currency peg, has gummed up the machinery and has allowed the situation to grow dangerously out of kilter.