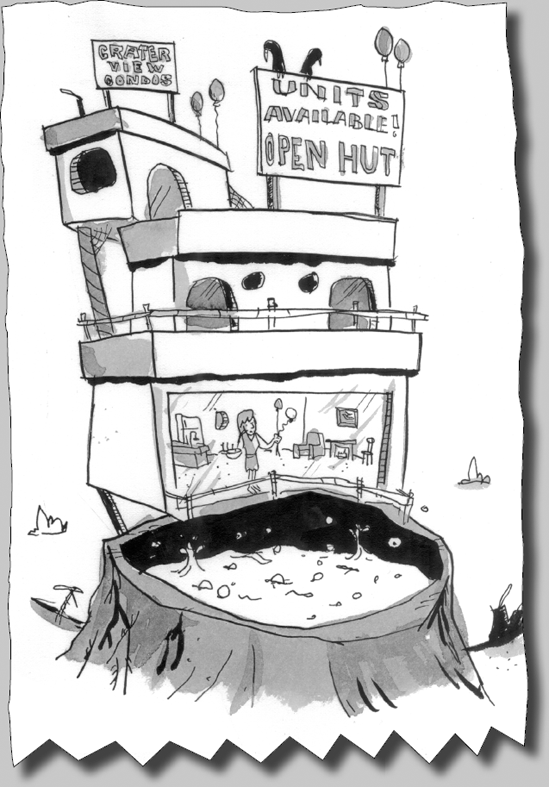

It's hard to say when the market first turned. Perhaps it was the high-profile demise of the Crater View Condominium Huts, which, despite their amenities, ample square footage, and unmatched ocean and lava views, somehow failed to attract buyers.

As Manny Fund was the principal underwriter of the project, the investment company took a big hit when the developer defaulted on the construction loan. When nervous real estate investors saw the losses at the Crater View Condos, many of them took a hard look at some of their other risky real estate holdings. A distinct apprehension began to spread.

Soon, buyers—both large and small—figured the market had peaked. Many decided that they should sell their current properties, take their frothy profits, and wait for a more favorable time to reinvest.

There was just one problem—everyone was thinking the same thing at the same time. Most of the owners in the market never intended to hold their properties very long to begin with. So when the market began to turn, everybody wanted out. In short order, the island was awash with sellers and devoid of buyers. When that happened, the unthinkable occurred—prices didn't just decline in a modest, orderly fashion...they started plummeting. The hut glut had quickly turned into a massive hut rut.

Suddenly, hut ownership, once a surefire ticket to easy wealth, became a decidedly riskier proposition. With prices no longer rising, huts did not create any fish equity to extract and profits from quick resales were no longer possible. With the pot of gold no longer looming at the end of the rainbow, uncomfortably high loan payments became a burden hardly worth bearing

This situation was further complicated when temporally low introductory teaser rates reset higher, which made the homes instantly unaffordable for those borrowers whose only hope had been a quick resale or fish-traction. With homes worth less than their underlying loans, the temptation to walk away from big payments became intense. This was especially true for those who did not put any fish down at purchase. Having made no prior commitment of funds, these borrowers had nothing to lose by not paying their mortgages and allowing the bank to foreclose.

As more and more borrowers defaulted, Manny Fund's securitized loan business was soon declared bankrupt. The losses overwhelmed the venerable institution. Shortly thereafter both Fishy and Finnie admitted that they too were belly-up.

With consumers no longer extracting hut equity, the industries that grew up around the hut glut also fell into crisis. Hut builders, design consultants, window trimmers, and appliance salespeople werelaid off in droves.

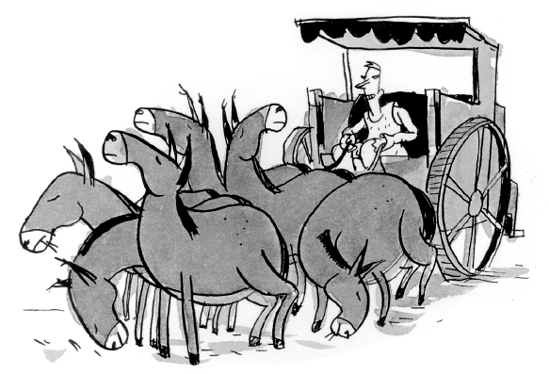

Other seemingly disparate industries were impacted as well. The Usonian donkey cart makers had benefited greatly from hut equity extractions. Effortlessly pulling fish out of their appreciating huts had allowed islanders to buy bigger and bigger carts. In the go-go days, many of these wagons became so large that four or five donkeys were needed to pull them. (This was problematic as most of the donkeys were imported.) With no more hut equity to tap into, sales of these "grass guzzlers" plummeted, and the cart companies fell into bankruptcy.

The island became ensnared in the worst economic crisis since the great monsoon of Franky Deep's era. Growing desperate, the unemployed workers converged on the Senate demanding solutions.

After years of denying any weakness in the economy, the island's Senator-in-chief, George W. Bass, belatedly set to work fixing the problem.

With strong unanimity, his advisors recommended bold incentives that would get consumers spending again, especially on huts. Without any understanding of why savings and production fuel economic growth, the Senate decided on a program of bailouts and stimuli.

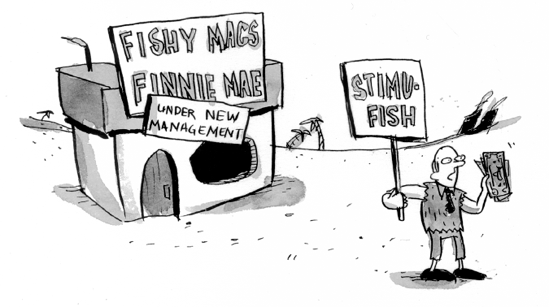

Their first rescue was for Finnie and Fishy, which were taken over by the Senate directly and were stocked with new Fish Reserve Notes to cover their losses. The reorganized companies were ordered by their new management (the Senate) to offer ultra-low-rate hut loans to anyone who had the wherewithal to fill out an application.

It was hoped that the continued availability of easy credit would increase demands for huts, and thereby stop the slide in prices.

When these policies failed to stem the fall, Bass called an emergency meeting of his top advisors, including Brent Barnacle, who had previously assured him that prosperity would be endless.

"Hey, Barney," said the Senator-in-Chief in his trademark folksy demeanor. "You sure sold me a bill of goods on this one. I thought this economy thing was supposed to be simple. You know, they make 'em, we eat 'em, and everyone gets a hut or two! I mean how do we get the shark to smell the chum on this one?"

The other senators searched for the meaning of his metaphor. Perhaps none existed.

"Well, sir, the problem is quite simple," said Hank Plankton, the new head fish accountant. "Hut prices are falling, so citizens don't feel as wealthy as they did before. As a result, they have stopped spending. If we can push hut prices back up, people will start spending again."

"Cool, Plankie, I knew this was gonna be a breeze," said Bass. "How we gonna do that? Do we have someone in charge of that? Sounds like a cool job. Maybe I'll appoint one of my biggest donors."

"Well, sir, it's not quite that simple," said Plankton. "We can't just mandate that hut prices go back up. As you know, we have kept Finnie and Fishy lending. Unfortunately, that alone is not enough. For some reason the people don't want to borrow. Perhaps the loan application is still too complicated. But for now, we need to push interest rates lower and then give people more tax breaks to buy huts. That should create a lot of demand for loans, which should stop hut prices from falling and get hut builders busy again."

Plankton continued laying out his plans. "We also need to make sure that Manny Fund remains solvent. The company owes a lot of fish to a lot of people. If it were to go down, the entire island economy would utterly collapse. We also need to make sure that no one who invested in Manny Fund loses any fish. If we don't do this, I'm sure that we would all starve...especially the children."

"Well, that aint gonna happen on my watch, Plankie," replied Bass. "Tell them that we're gonna come to the rescue with a bailout. Hey, didn't you used to work there?"

"Yes, Mr. Senator, I was the president of the company. But I really don't see how that has any relevance to this conversation, and frankly, I resent the insinuation."

"Aw heck, Hank, I was just funnin," Bass continued. "Okay. After we get hut prices back up, and keep Manny and the boys in business, how are we gonna get people spending again? Where they gonna get the fish? I mean last time I checked, we were all a bit tapped in the tuna department. Isn't that why they're outside holding pitchforks?"

"Well, sir, we plan on distributing new Fish Reserve Notes to all the citizens. That should get them spending."

"That's cool. But where we gonna get the fish? Haven't our technicians stretched the sturgeons about a far as they can?"

"Well, sir, we have some new commitments from the Sinopians. They have offered to buy the Water Works system for 100,000 fish."

"Hold on honcho. Sell the Water Works? You're talking about jeopardizing our national security! They'd have me tarred and feathered for giving up something like that to those carpetbaggers. Couldn't they just make it a loan instead?"

After months of tense negotiations, Bass's ambassadors convinced the Sinopians that a sale of the Water Works was politically impossible. Instead, the Sinopians somewhat bitterly agreed to make a 100,000-fish loan.

"Hey, Hank," said Bass, after word came back of the successful outcome. "Great news, we got the loan. Just one thing. How are we gonna pay it back?"

"Well, sir, I expect that we will just print up another batch of Fish Reserve Notes. But this time we will use our very best paper."

"Yeah, but what if they won't take them? Aren't we getting a lot of guff from them people already about the value of our notes? It's like that Chuck DeBongo guy a few years back. Won't they just start selling if we issue so many more notes?"

"Highly unlikely, sir. Think about how many Fish Reserve Notes they already have. If they stop taking them, those notes will lose even more value. We've got them over a barrel. And if things get dicey, we'll just remind them of our 'Strong Fish Policy!'"

"Oh, yeah. I forgot about that. It's nice having that one in your back pocket. Is that where we go out and catch more fish to back up our notes?"

"No sir," chimed Brent Barnacle. "The Strong Fish Policy is all about tone. We don't actually do anything. We just say 'Strong Fish Policy' really clearly and loudly again and again. Also, it helps if you clench your fist and beat it on the table when you say the words."

"Right you are, Barney. Let's just say I know a little something about acting tough. Mission accomplished! Now let's go surfin'!"

It's hard to overstate the impact the housing boom made on the economy as a whole. During the height of the mania, the financing, construction, and furnishing of homes had become the central dynamo of the U.S. economy. And while everyone acknowledged the good fortune, few spared much concern about the future costs.

In addition to the profits made by real estate "flippers" (those who serially bought and sold properties), homeowners extracted hundreds of billions of dollars per year from their homes. The process turned houses into tax-free ATM machines. People used the money to renovate their homes, take vacations, pay for college, buy cars and electronics, and just generally live better than they would have if their homes had not appreciated in value.

But the wealth was simply a mirage.

In his book Irrational Exuberance economist Robert Shiller determined that in the 100 years between 1900 and 2000, home prices in the United States increased by an average of 3.4 percent per year (which is just slightly higher than the average rate of inflation). There were good reasons for this. Prices were firmly tied to people's ability to pay, which is a function of income and credit availability.

But from 1997 to 2006 national home prices gained an astounding 19.4 percent per year on average. Over that time incomes barely budged. So why could people pay so much? The difference was credit, which government policy made much cheaper and easier to get. But credit could not expand forever, and eventually conditions tightened. When they did, there was nothing to hold prices up.

So when the market crested, the easy money that for years had poured into the economy stopped flowing. Even if there had been no other economic reversals that followed the housing bust (which there were), the economy would have had to shrink without all the free cash. A recession was not only inevitable but absolutely necessary to rebalance the economy.

But when the economy started to contract, lawmakers and economists treated the development not as the inevitable consequence of years of easy money and overspending, but as the problem itself. In other words, they mistook the cure for the disease.

The policy goals of both the Bush and Obama administrations have been to encourage consumers to spend as they had before the housing crash. But where will the money come from? If unemployment rose, and incomes and home prices fell, where would consumers get the money?

Economists have declared that if the people can't spend, the government needs to step up and do it for them. But the government doesn't have any money. All it has is what it collects in taxes and what it borrows or prints.

For now, this process is just creating massive public debt ($1.6 trillion per year and counting). And although the numbers look bad, we are still able to sell most of this debt on the open market, primarily to foreigners.

But our "good fortune" can't last forever. Ultimately the U.S. government will have only two options: default (tell our creditors that we can't pay, and negotiate a settlement) or inflate (print money to pay off maturing debt). Either option will lead to painful consequences. Default, which does offer the possibility of a real reckoning and a fresh beginning, is actually the better alternative. Unfortunately, while inflation is worse, it is also the more politically expedient.